Abstract

Background

Studies have demonstrated the role of ulcerative and non-ulcerative sexually transmitted infections (STI) in HIV transmission/acquisition risk; less is understood about the role of non-specific inflammatory genital abnormalities.

Methods

HIV-discordant heterosexual Zambian couples were enrolled into longitudinal follow-up (1994–2012). Multivariable models estimated the effect of genital ulcers and inflammation in both partners on time-to-HIV transmission within the couple. Population-attributable fractions (PAFs) were calculated.

Results

A total of 207 linked infections in women occurred over 2756 couple-years (7.5/100 CY) and 171 in men over 3216 CY (5.3/100 CY). Incident HIV among women was associated with a woman’s non-STI genital inflammation (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 1.55; PAF = 8%), bilateral inguinal adenopathy (BIA; aHR = 2.33; PAF = 8%), genital ulceration (aHR = 2.08; PAF = 7%) and the man’s STI genital inflammation (aHR = 3.33; PAF = 5%), BIA (aHR = 3.35; PAF = 33%) and genital ulceration (aHR = 1.49; PAF = 9%). Infection among men was associated with a man’s BIA (aHR = 4.11; PAF = 22%) and genital ulceration (aHR = 3.44; PAF = 15%) as well as with the woman’s non-STI genital inflammation (aHR = 1.92; PAF = 13%) and BIA (aHR = 2.76; PAF = 14%). In HIV-M+F- couples, the man being uncircumcised. with foreskin smegma. was associated with the woman’s seroconversion (aHR = 3.16) relative to being circumcised. In F+M- couples, uncircumcised men with BIA had an increased hazard of seroconversion (aHR = 13.03 with smegma and 4.95 without) relative to being circumcised. Self-reporting of symptoms was low for ulcerative and non-ulcerative STIs.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm the role of STIs and highlight the contribution of non-specific genital inflammation to both male-to-female and female-to-male HIV transmission/acquisition risk. Studies are needed to characterize pathogenesis of non-specific inflammation including inguinal adenopathy. A better understanding of genital practices could inform interventions.

Keywords: Couples’, voluntary HIV counselling and testing, discordant couples, HIV risk, genital ulceration and inflammation, longitudinal cohort, Zambia

Background

In seeking an explanation for differential HIV transmission probabilities regionally and per sex act, genital ulceration and inflammation (GUI) emerged as important transmission co-factors in the late 1980s and early 1990s.1–3 Decades of observational research implicate several inflammatory sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomonas and ulcerative STIs as well as syphilis and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). Reviews4,5 indicate that few studies consider the effect of GUIs in both sexual partners on HIV risk, or address non-STI inflammatory abnormalities such as candida, bacterial vaginosis (BV), genital discharge or inflammation more broadly.6–9 Inflammatory processes can recruit HIV-infected or target cells to the genitalia, thereby increasing risks of both transmission and acquisition. Studies of inflammatory markers confirm that cells are associated with high viral loads (VL) in cervico-vaginal fluids,10 and cytokine markers11–14 and innate antimicrobial responses15,16 are linked to HIV acquisition. Causes of these inflammatory processes warrant closer investigation.

Though antiretroviral treatment (ART) reduces HIV-1 transmission,17 it does not alter genital cytokine levels in HIV+ women,18 and adherence and retention are poor in Zambia.19–22 Low-cost strategies that reduce HIV risk independently of ART remain imperative. Building on what is known about the impact of inflammation and ulceration in heterosexual HIV transmission, we quantify the risk and population-attributable fraction (PAF) associated with a wide range of both sexually transmitted and more common non-sexually transmitted GUIs among ART-naïve Zambian serodiscordant couples over 18 years of follow-up.

Methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Office for Human Research Protections-registered Institutional Review Boards at Emory University and the University of Zambia. Joint written informed consent was obtained from all participating couples.

Study participants and staff

Heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples (M+F- or F+M-) were recruited from couples’ voluntary HIV counselling and testing (CVCT) in Lusaka, Zambia.23,24 Enrolment was continuous in the open cohort through 1994–2012 and follow-up continued quarterly. Risk reduction counselling was provided at enrolment and at every visit. Free outpatient health care was provided by Zambian registered nurses, clinical officers or general medicine physicians, and specialists in internal medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology, and laboratory diagnostics. Clinical and laboratory staff received training in good clinical practices and standard operating procedures, including quality assurance and control. Couples were censored if either partner died or was lost to follow-up, the couple separated or the HIV+ partner initiated ART. Criteria for ART changed over time after it became available in government clinics, based on evolving World health organization (WHO) guidelines (CD4 < 200 cells/ml pre-2006, < 350 cells/ml post-2006).25 HIV+ participants were referred for ART; those confirmed to have initiated ART were discharged from the cohort to reduce possible confusion from enrolment in multiple programmes.

Longitudinal data collection

Procedures changed over time as a function of available resources and study priorities. Over 1994-2002, both partners were seen quarterly and had routine genital examinations. Beginning in 2003, physical and genital examinations were performed at baseline, annually and when symptoms were reported. Plasma banking for VL testing began in 1999, and p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) screening began in 2003. Over 2007-08, HIV partners were seen at months 0,1,2 and3, and quarterly at which time sexual exposures were assessed by self-report or biological markers of condomless sex.26 HIV partners with one or more exposures received monthly HIV testing until the next quarterly visit, at which time the assessment was repeated. Over 2008-12, all HIV partners were tested for HIV monthly. When HSV-2 ELISA was available in 2005, these tests were run on banked and new baseline samples. Due to funding constraints, follow-up was truncated at 36 months (2010) and 24 months (2011).

Exposures of interest

Exposures measured at baseline and follow-up visits included: self-reported genital ulcer, urethral or vaginal discharge, dysuria or dyspareunia; genital examination findings including external or internal genital inflammation (redness, swelling, exudate, discharge, irritation or tenderness) or genital or perianal ulceration (including erosion or friability); and laboratory studies including rapid plasma regain (RPR; BD Macro-VueTM, Becton-Dickinson Europe, with Treponema pallidum haemagglutination assays (TPHAs) confirmation when available27); vaginal wet mount for detection of trichomonas, clue cells (BV) and candida, including potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations for the whiff test (BV).28,29 Gonorrhea culture and Gram staining both routinely and in the presence of endocervical pus was piloted, but very few positive results were obtained. These expensive and time-consuming procedures were discontinued and diagnosis was based on endocervical or urethral discharge.

Diagnosis and treatment were based on the best available information including self-report, physical examination and laboratory results. Incident positive RPR prompted treatment of both partners for syphilis,27 and self-report or clinical diagnosis of RPR-negative ulcer was treated based on clinical presentation and HSV-2 serology. Urethral discharge or dysuria in men, or endocervical discharge were detected, both partners were treated for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Both partners were treated when trichomonas was detected on vaginal wet mount, and women with candida or BV were treated given symptoms. Unilateral inguinal adenopathy (UIA) and bilateral inguinal adenopathy (BIA) were not treated.

Composite variables

For each 3-monthly interval, composite variables were created. The genital inflammation composite had two mutually exclusive levels: inflammatory STIs (clinical or laboratory diagnosis or treatment of gonorrhea, chlamydia or trichomonas); or non-inflammatory STIs (reported discharge, dysuria, dyspareunia; observed discharge or inflammation of external or internal genitalia; and/or laboratory diagnosis of candida or BV) with no indication of an inflammatory STI. The composite for genital ulcer included observed or reported ulcers and/or incident positive RPR.

Other covariates

We measured: baseline age, years cohabiting, income, literacy, current pregnancy and number of previous pregnancies, clinical and laboratory stage as developed by our group for Kigali and modified for Zambia30,31 and VL of HIV+ partners;32 male circumcision (MC); HSV-2 serological positivity; STI and number of sexual partners in the past year; and contraceptive method. Time-varying measures of unprotected sex with the study partner, sperm present on a vaginal swab wet mount, contraceptive use and pregnancy were measured.

Outcome of interest

The outcome was time-to-incident HIV infection genetically linked to the study partner. HIV testing of HIV partners was conducted at 1- to 3-monthly intervals using rapid serological tests.33 When possible, plasma from the last antibody-negative sample was tested by p24 ELISA and RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR). To determine if infections were linked or acquired outside the partnership, conserved nucleotide sequences (gag, gp120, gp41, long terminal repeat regions) from both partners were PCR-amplified, and pairwise genetic distances were calculated for these sequenced regions.34,35 Date of infection was defined based on available data, as the minimum of: the midpoint between the last negative and first positive antibody date (only eight seroconverters had more than 6 months between last negative and first positive visits); 2 weeks before first antigen-positive test date; or 2 weeks before first VL-positive/antibody-negative test date.

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted with SASv9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Couples experiencing unlinked seroconversion were excluded from analysis.

HIV incidence

HIV incidence rates (the number of incident infections per couple-year (CY) of follow-up from enrolment until either the outcome occurred or the couple were censored) were calculated by months since enrolment, to explore cohort effects, and differences were evaluated by log-rank tests for linear trend. Months since enrolment were also dichotomized (months > 0-3 versus > 3), and differences evaluated by mid-P exact tests to compare incidence prior to joint testing and counselling (months > 0-3, reflecting transmissions occurring in the seroconversion window before CVCT) compared with rates for > 3 months of follow-up.

Exposures

Exposures are described stratified by HIV transmission status using counts and percentages (categorical variables), means and standard deviations (normal continuous variables) and medians and interquartile ranges (non-normal continuous variables). Bivariable associations were evaluated via unadjusted Cox models. Crude hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P-values are reported. We also calculated the proportion of patients with STI diagnoses that reported symptoms before diagnosis, for 1994-2002.

Multivariable models

Multivariable Cox models accounting for repeated observations evaluated predictors of time-to-HIV infection. Confounding was assessed using a data-based criteria method to identify variables that changed the point estimate of any exposure of interest by +/-10%. Candidate variables were evaluated for multi-collinearity (condition indices > 30, variance decomposition proportions > 0.5); collinear variables with weaker associations with the outcome were removed. The proportional hazards assumption was confirmed for time-independent covariates. We explored for potential interaction by: cohabitation length (< 1 year versus ≥ 1 year); circumcision and smegma; and circumcision, smegma and BIA. A ‘generalized’ R-squared statistic (with > 60% thought to be meaningful) was calculated for each model as:36

where LRT (likelihood ratio test) is the difference between the -2log likelihood for the null model with no covariates and the fitted model, and n is the number of observations. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) are reported.

Population-attributable fractions

PAFs were calculated for genital inflammation and ulceration composites using standard formulae37–39 with aHRs as the measure of relative risk:40–42

where p is the proportion of cases exposed. Confidence intervals around PAFs were calculated.43,44

Sub-analyses

For the data collected over 1994-2002, we explored interactions between circumcision, foreskin smegma and BIA in men.

Sensitivity analyses

To explore the possibility of GUI exposure misclassification, we built models assuming a random 15% of exposures preceding seroconversion were incorrectly classified as negative, and another model assuming 15% of GUI exposures preceding seroconversion were incorrectly classified as positive. We also constructed a model after multiple imputation, carried out using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods which assume that the variables have a joint multivariate normal distribution. Simulation studies indicate that this common imputation method typically leads to robust estimates regardless of true normality.45,46

Results

Follow-up and transmission

A total of 1348 M+F- couples were followed for a median of 430 (interquartile range = 767) days; 207 linked transmissions occurred in women over 2756 CY (7.5/100 CY; 95% CI: 6.5-8.6). Follow-up among 1601 F+M- couples was a median of 448 (interquartile range = 730) days; 171 linked transmissions occurred in men over 3216 CY (5.3/100 CY; 95% CI: 4.5-6.2). During this time, 45 unlinked infections occurred in women and 55 in men; these couples were excluded from analysis. Among study couples, 57% had at least 1 year of follow-up, 35% had ≥ 2 years and 22% had ≥ 3 years.

HIV incidence

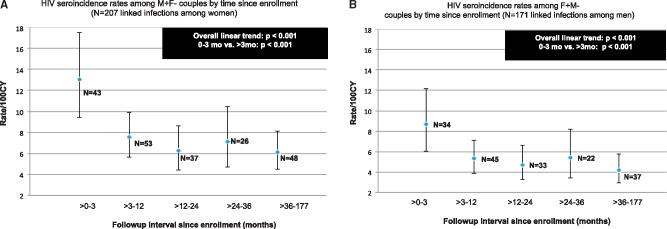

Incidence in women decreased between > 0-3 months (13.0/100 CY; 95% CI: 9.4-17.5) versus > 3 months of follow-up (6.7/100 CY; 95% CI: 5.7-7.8) (P < 0.001, Figure 1A). This was also true for men: > 0-3 months (8.7/100 CY; 95% CI: 6.0-12.2) versus > 3 months (4.8/100 CY; 95% CI: 4.0-5.7) (P < 0.001, Figure 1B). Rates of transmission from M+F- were consistently higher than for F+M-. Follow-up time was predictive in unadjusted and adjusted models (> 0-3 months versus > 3 months, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

HIV seroincidence rates per 100 couple years (CY) and 95% confidence interval bars among Zambian women and men in HIV discordant relationships, Ns indicate number of seroconversions occurring in each time interval.

Baseline exposures

Exposures associated with transmission included lower men’s and women’s ages, fewer years cohabiting, fewer previous pregnancies and increasing baseline VL of the HIV+ partner (Table 1). Among M+F- couples, the woman’s illiteracy and pregnancy at baseline were associated with transmission. Among F+M- couples, the man being uncircumcised was associated with transmission.

Table 1.

Descriptive analyses of baseline covariates by seroconversion outcomes among Zambian women and men in HIV discordant relationships

| M+F- couples |

F+M- couples |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non- seroconverters (N = 1141) |

Linked transmissions (N = 207) |

HR | 95% CI | P-value | Non- seroconverters (N = 1430) |

Linked transmissions (N = 171) |

HR | 95%CI | P-value | |||

| N (%, SD) | N (%, SD) | N (%, SD) | N (%, SD) | |||||||||

| Age of man (years)a | 35.5 (7.7) | 33.5 (7.5) | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | < 0.001 | 35.4 (8.5) | 33.1 (8.0) | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.001 |

| Age of woman (years)a | 28.8 (7.0) | 26.3 (6.3) | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 | < 0.001 | 29.0 (6.8) | 27.0 (6.2) | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.007 |

| Years cohabitinga | 8.3 (6.7) | 6.7 (5.7) | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.002 | 6.0 (6.0) | 4.7 (5.0) | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.002 |

| Monthly household income (USD)b | 62.1 (85.6) | 49.1 (61.6) | 1.00 | 0.997 | 1.001 | 0.35 | 64.2 (84.6) | 50.0 (55.7) | 1.00 | 0.997 | 1.001 | 0.26 |

| Woman reads Nyanja | ||||||||||||

| Yes, easily | 272 (24) | 35 (17) | ref | 379 (27) | 36 (22) | ref | ||||||

| With difficulty/no | 857 (76) | 167 (83) | 1.45 | 1.01 | 2.09 | 0.05 | 1037 (73) | 131 (78) | 1.19 | 0.83 | 1.73 | 0.35 |

| # previous pregnanciea | 3.7 (2.5) | 3.1 (2.1) | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.001 | 3.2 (2.2) | 3.0 (2.2) | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.02 |

| HIV stage of positive partner | ||||||||||||

| Stage I | 294 (26) | 49 (24) | 1.06 | 0.73 | 1.52 | 0.77 | 600 (42) | 64 (37) | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.34 | 0.66 |

| Stage II | 369 (33) | 81 (39) | 1.04 | 0.76 | 1.43 | 0.80 | 398 (28) | 55 (32) | 1.00 | 0.68 | 1.46 | 0.99 |

| Stage III-IV | 467 (41) | 76 (37) | ref | 420 (30) | 52 (30) | ref | ||||||

| VL of positive partner (log10 copies/mla | 4.6 (1.0) | 5.1 (0.7) | 1.66 | 1.36 | 2.04 | < 0.001 | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.8 (0.7) | 1.45 | 1.23 | 1.71 | < 0.001 |

| Circumcised manc | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 89 (8) | 15 (7) | ref | 267 (19) | 12 (7) | ref | ||||||

| No | 1039 (92) | 191 (93) | 1.22 | 0.72 | 2.06 | 0.47 | 1160 (81) | 159 (93) | 2.69 | 1.49 | 4.85 | 0.001 |

| RPR status of man | ||||||||||||

| Positive | 83 (7) | 22 (11) | 1.15 | 0.74 | 1.81 | 0.39 | 95 (7) | 22 (13) | 1.26 | 0.80 | 1.97 | 0.32 |

| Negative | 1057 (93) | 185 (89) | ref | 1333 (93) | 149 (87) | ref | ||||||

| RPR status of woman | ||||||||||||

| Positive | 74 (6) | 16 (8) | 0.93 | 0.56 | 1.56 | 0.79 | 113 (8) | 24 (14) | 1.14 | 0.74 | 1.76 | 0.56 |

| Negative | 1066 (94) | 191 (92) | ref | 1315 (92) | 147 (86) | ref | ||||||

Variables not associated with the outcome (not tabled): contraceptive method at baseline, male literacy, past year history of sexually transmitted infections, number of sexual partners in the last year, HSV-2 serology status of womanor man. P-values are two-tailed from crude (unadjusted) Cox models. Viral load collected beginning in 1999. Counts may not sum to total intervals due to missing data.

USD, United States dollar; ref, reference value; SD, standard deviation.

Indicates a continuous variable, mean and standard deviation reported and HRs are estimated per unit increase.

Indicates a non-normally distributed continuous variable, median and interquartile range reported.

Circumcised at baseline or ever during follow-up.

Time-varying exposures

Time-varying exposures associated with male-to-female transmission included non-STI inflammation in women and STI inflammation, genital ulceration and BIA in both partners (Table 2). Female-to-male transmission was associated with non-STI genital inflammation and BIA in both partners and genital ulceration in men.

Table 2.

Descriptive analyses of time-varying covariates by HIV seroconversion outcomes among Zambian women and men in HIV discordant relationships

| M+F- couples |

F+M- couples |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non- sero-converter (N = 13547 intervals) |

Linked transmission (N = 207 intervals) |

HR | 95%CI | P-value | Non- sero- converter (N = 13,237 intervals) |

Linked transmission (N = 171 intervals) |

HR | 95%CI | P-value | |||

| Exposures of interest | N (%, SD) | N (%, SD) | N (%, SD) | N (%, SD) | ||||||||

| Genital inflammation of woman | ||||||||||||

| STI | 500 (4) | 20 (10) | 2.48 | 1.54 | 4.01 | < 0.001 | 851 (6) | 15 (9) | 1.61 | 0.92 | 2.82 | 0.10 |

| Non-STI | 1282 (10) | 44 (21) | 1.86 | 1.25 | 2.77 | < 0.01 | 1459 (11) | 45 (26) | 3.11 | 1.97 | 4.90 | < 0.001 |

| No | 11675 (87) | 144 (69) | ref | 10927 (83) | 111 (65) | ref | ||||||

| BIA of woman | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 299 (2) | 30 (14) | 4.43 | 2.88 | 6.81 | < 0.001 | 1057 (8) | 38 (22) | 2.84 | 1.82 | 4.43 | < 0.001 |

| No | 13158 (98) | 177 (86) | ref | 12180 (92) | 133 (78) | ref | ||||||

| Genital ulcer of woman | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 573 (4) | 29 (14) | 3.00 | 1.97 | 4.56 | < 0.001 | 1118 (8) | 26 (15) | 1.51 | 0.97 | 2.36 | 0.07 |

| No | 12884 (96) | 178 (86) | ref | 12119 (92) | 145 (85) | ref | ||||||

| Genital inflammation of man | ||||||||||||

| STI | 189 (1) | 14 (7) | 4.01 | 2.31 | 6.98 | < 0.001 | 145 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.02 | 0.25 | 4.16 | 0.98 |

| Non-STI | 111 (1) | 5 (3) | 2.03 | 0.82 | 5.05 | 0.127 | 188 (1) | 10 (6) | 2.68 | 1.36 | 5.26 | < 0.01 |

| No | 13157 (98) | 188 (91) | ref | 12904 (97) | 159 (93) | ref | ||||||

| BIA of man | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2451 (18) | 98 (47) | 4.49 | 3.07 | 6.58 | < 0.001 | 859 (6) | 49 (29) | 6.29 | 4.05 | 9.75 | < 0.001 |

| No | 11006 (82) | 109 (53) | ref | 12378 (94) | 122 (71) | ref | ||||||

| Genital ulcer of man | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1824 (14) | 52 (25) | 1.74 | 1.26 | 2.41 | 0.001 | 719 (5) | 37 (22) | 5.02 | 3.43 | 7.35 | < 0.001 |

| No | 11633 (86) | 155 (75) | ref | 12518 (95) | 134 (78) | ref | ||||||

| Sexual behaviour and family planning characteristics | ||||||||||||

| No. unprotected sex acts with study partner since last visita | 2.4 (8.5) | 3.7 (10.3) | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 3.9 (12.4) | 9.9 (21.8) | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | < 0.001 |

| Any unprotected sex with study partner since last visit | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 4087 (30) | 87 (42) | 1.39 | 1.04 | 1.84 | 0.02 | 4646 (36) | 100 (58) | 2.39 | 1.75 | 3.25 | < 0.001 |

| No | 9433 (70) | 119 (58) | ref | 8409 (64) | 71 (42) | ref | ||||||

| Sperm present on vaginal swab wet mount | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 831 (6) | 25 (13) | 1.52 | 0.98 | 2.37 | 0.06 | 811 (6) | 25 (15) | 2.03 | 1.28 | 3.21 | < 0.01 |

| No | 12685 (94) | 183 (87) | ref | 12420 (94) | 147 (85) | ref | ||||||

| Current pregnancy | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1130 (9) | 27 (14) | 1.41 | 0.94 | 2.12 | 0.097 | 819 (7) | 26 (16) | 2.27 | 1.49 | 3.46 | < 0.001 |

| No | 11168 (91) | 171 (86) | ref | 10575 (93) | 135 (84) | ref | ||||||

| Incident pregnancy | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 487 (4) | 16 (8) | 1.40 | 0.84 | 2.34 | 0.20 | 435 (4) | 11 (7) | 1.56 | 0.84 | 2.88 | 0.16 |

| No | 11253 (96) | 185 (92) | ref | 10838 (96) | 150 (93) | ref | ||||||

| Associations with foreskin smegma (pre-2002 only) | ||||||||||||

| Circumcision status by smegma | ||||||||||||

| Circumcised | 383 (9) | 6 (6) | ref | 737 (20) | 7 (10) | ref | ||||||

| Uncircumcised and no smegma | 3356 (82) | 78 (78) | 1.49 | 0.65 | 3.41 | 0.35 | 2580 (71) | 49 (71) | 2.06 | 0.93 | 4.57 | 0.08 |

| Uncircumcised and smegma | 367 (9) | 16 (16) | 2.82 | 1.10 | 7.24 | 0.03 | 323 (9) | 13 (19) | 3.73 | 1.47 | 9.45 | 0.01 |

| Circumcision status by man's BIA | ||||||||||||

| Circumcised | ||||||||||||

| BIA of man: Yes | 224 (5) | 2 (2) | 0.42 | 0.08 | 2.32 | 0.32 | 125 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.91 | 0.11 | 7.68 | 0.93 |

| BIA of man: No | 159 (4) | 4 (4) | ref | 612 (17) | 6 (9) | ref | ||||||

| Uncircumcised and no smegma | ||||||||||||

| BIA of man: Yes | 1773 (43) | 51 (51) | 1.25 | 0.44 | 3.57 | 0.67 | 542 (15) | 27 (39) | 5.28 | 2.12 | 13.15 | < 0.001 |

| BIA of man: No | 1583 (39) | 27 (27) | 0.75 | 0.26 | 2.17 | 0.60 | 2038 (56) | 22 (32) | 1.17 | 0.47 | 2.90 | 0.74 |

| Uncircumcised and smegma | ||||||||||||

| BIA of man: Yes | 226 (6) | 12 (12) | 2.32 | 0.73 | 7.45 | 0.16 | 114 (3) | 6 (9) | 5.50 | 1.72 | 17.58 | < 0.01 |

| BIA of man: No | 141 (3) | 4 (4) | 1.34 | 0.33 | 5.48 | 0.68 | 209 (6) | 7 (10) | 3.22 | 1.07 | 9.74 | 0.04 |

Foreskin smegma recorded from 1994 to 2002. P-values are two-tailed from Cox models. Variables not associated with the outcome (not tabled): time-varying contraceptive methods, unilateral inguinal adenopathy. Counts may not sum to total intervals due to missing data.

Indicates a continuous variable, mean and standard deviation reported.

Multivariable models

Collinear variables included men’s and women’s ages, ages and years cohabiting and age and number of previous pregnancies (Tables 3 and 4). Women’s age was retained. There was no interaction by cohabitation length. Genital ulcer of HIV+ women was not included in multivariable models because of lower statistical significance and magnitude of the crude point estimate.

Table 3.

Multivariable model of predictors of time to HIV transmission among Zambian women and men in HIV discordant relationships

| Primary modela,b | M+F- couples |

F+M- couples |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposures of interest | aHR | 95% CI | P-value | aHR | 95% CI | P -value | ||

| Genital inflammation of woman | ||||||||

| STI | 1.36 | 0.76 | 2.43 | 0.30 | 1.01 | 0.50 | 2.05 | 0.97 |

| Non-STI | 1.55 | 1.01 | 2.38 | 0.04 | 1.92 | 1.15 | 3.22 | 0.01 |

| No | ref | ref | ||||||

| BIA of woman | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.33 | 1.43 | 3.81 | < 0.01 | 2.76 | 1.69 | 4.51 | < 0.001 |

| No | ref | ref | ||||||

| Genital ulcer of woman | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.08 | 1.27 | 3.41 | < 0.01 | ||||

| No | ref | |||||||

| Genital inflammation of man | ||||||||

| STI | 3.33 | 1.79 | 6.17 | < 0.01 | e | |||

| Non-STI | 1.18 | 0.43 | 3.21 | 0.75 | 1.19 | 0.51 | 2.77 | 0.69 |

| No | ref | ref | ||||||

| BIA of man | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.35 | 2.24 | 5.03 | < 0.001 | 4.11 | 2.52 | 6.72 | < 0.001 |

| No | ref | ref | ||||||

| Genital ulcer of man | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.49 | 1.05 | 2.11 | 0.03 | 3.44 | 2.20 | 5.38 | < 0.001 |

| No | ref | ref | ||||||

| Baseline and time-varying variables | ||||||||

| Age of woman (per year increase) | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.42 |

| Woman reads Nyanja | ||||||||

| Yes, easily | ref | |||||||

| With difficulty/not at all | 1.22 | 0.82 | 1.80 | 0.32 | ||||

| Circumcised manc | ||||||||

| Yes | ref | |||||||

| No | 2.10 | 1.12 | 3.95 | 0.02 | ||||

| VL of positive partner (per log10 copies/ml increase) | 1.68 | 1.35 | 2.08 | < 0.001 | 1.80 | 1.44 | 2.23 | < 0.001 |

| Any self-reported unprotected sex with study partner since last visit | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.38 | 1.01 | 1.88 | 0.04 | 1.91 | 1.33 | 2.75 | < 0.01 |

| No | ref | ref | ||||||

| Sperm present on vaginal swab wet mount | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.41 | 0.88 | 2.26 | 0.15 | 1.73 | 1.03 | 2.91 | 0.04 |

| No | ref | ref | ||||||

| Current pregnancy | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.35 | 0.79 | 2.31 | 0.27 | ||||

| No | ref | |||||||

| Interval since enrolment | ||||||||

| 0–3 months | 4.30 | 2.75 | 6.72 | < 0.001 | 5.07 | 2.93 | 8.78 | < 0.001 |

| < 3 months | ref | ref | ||||||

| Pre-2002 model 1d | ||||||||

| Circumcision and smegma status | ||||||||

| Circumcised | ref | ref | ||||||

| Uncircumcised and no smegma | 1.68 | 0.93 | 3.04 | 0.08 | 4.50 | 2.36 | 8.59 | < 0.001 |

| Uncircumcised and smegma | 3.16 | 1.54 | 6.46 | < 0.01 | 8.59 | 3.72 | 19.86 | < 0.001 |

| Pre-2002 model 2d | ||||||||

| Circumcision status and smegma by man's BIA | ||||||||

| Circumcised | ||||||||

| BIA of man: Yes | 0.36 | 0.06 | 1.99 | 0.24 | ||||

| BIA of man: No | ref | |||||||

| Uncircumcised and no smegma | ||||||||

| BIA of man: Yes | 4.95 | 2.43 | 10.10 | < 0.001 | ||||

| BIA of man: No | 0.85 | 0.31 | 2.34 | 0.75 | ||||

| Uncircumcised and smegma | ||||||||

| BIA of man: Yes | 13.03 | 4.97 | 34.17 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| BIA of man: No | e | |||||||

Foreskin smegma recorded from 1994-2002. P-values are two-tailed from Cox models. Adjusted point estimate for genital ulcer of woman in F+M- primary model (not included in final models): aHR = 0.94, 95% CI:0.55-1.62 (P = 0.84).

‘Generalized’ R-squared = 0.63 for M+F- couples (primary model).

‘Generalized’ R-squared = 0.80 for F+M- couples (primary model).

Circumcised at baseline or ever during follow-up.

Controlling for the primary model variables.

Small sample size; a measure of association could not be estimated.

Table 4.

Attributable fraction in the population for exposures of interest significant in multivariable models

| M+F- |

F+M- |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary models | AFp | 95% CI | AFp | 95% CI | ||

| Genital inflammation of woman: Non-STI | 8% | 3.71 | 16.73 | 13% | 7.48 | 21.85 |

| BIA of woman | 8% | 5.94 | 11.75 | 14% | 11.24 | 17.93 |

| Genital ulcer of woman | 7% | 4.79 | 11.42 | |||

| Genital inflammation of man: STI | 5% | 3.77 | 6.02 | |||

| BIA of man | 33% | 30.19 | 36.58 | 22% | 18.56 | 25.36 |

| Genital ulcer of man | 8% | 4.24 | 17.17 | 15% | 13.88 | 16.97 |

| Pre-2002 model 1 | ||||||

| Uncircumcised and no smegma | 55% | 46.17 | 66.12 | |||

| Uncircumcised and smegma | 11% | 8.12 | 14.86 | 17% | 14.89 | 18.63 |

| Pre-2002 model 2 | ||||||

| Uncircumcised and no smegma and BIA of man | 31% | 26.18 | 37.29 | |||

| Uncircumcised and smegma and BIA of man | 8% | 7.17 | 9.01 | |||

Foreskin smegma recorded from 1994-2002.

Incident HIV among women was associated with the woman’s non-STI genital inflammation (aHR = 1.6; PAF = 8%), BIA (aHR = 2.3; PAF = 8%) and genital ulceration (aHR = 2.1; PAF = 7%), and the man’s STI genital inflammation (aHR = 3.3; PAF = 5%), BIA (aHR = 3.4; PAF = 33%) and genital ulceration (aHR = 1.5; PAF = 9%). The ‘generalized’ R-squared statistic was 63%.

Infection among men was associated with the woman’s non-STI genital inflammation (aHR = 1.9; PAF = 13%) and BIA (aHR = 2.8; PAF = 14%), and the man’s BIA (aHR = 4.1; PAF = 22%) and genital ulceration (aHR = 3.4; PAF = 15%). The ‘generalized’R-squared statistic was 80%.

In M+F- couples, 84% of trichomonas were detected without self-reported discharge; 78% (men) and 92% (women) of incident positive RPR results were detected with no self-reported genital ulcers; 32% (men) and 71% (women) of incident RPR-negative ulcers were detected without self- reported ulcer; and 28% (men) and 98% (women) of cases of gonorrhea and chlamydia were diagnosed with no self-reported symptoms.

In F+M- couples, 86% of trichomonas were detected without self-reported discharge; 90% (men and women) of incident positive RPR results were detected with no self- reported genital ulcers; 20% (men) and 65% (women) of incident RPR-negative ulcers were detected without self-reported ulcer; and 20% (men) and 92% (women) of cases of gonorrhea and chlamydia were diagnosed with no self-reported symptoms.

1994–2002 sub-analyses

In M+F- couples, being uncircumcised with foreskin smegma was associated with seroconversion (aHR = 3.2) relative to being circumcised. In F+M- couples, uncircumcised men with BIA had an increased hazard of seroconversion (aHR = 5.0 without smegma, aHR = 13.0 with smegma) relative to being circumcised (Table 3).

Sensitivity analyses

If 15% of GUI exposures before seroconversion were misclassified as false-negative, GUI exposures are more hazardous than in primary analyses (Appendix 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online), whereas if 15% of these GUI exposures were misclassified as false-positive, estimates were tempered toward the null (Appendix 2, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). For every variable in primary analyses, 87% of M+F- and F+M- cases were complete, and multiple imputation results were similar to primary analyses, with slightly more hazardous point estimates (Appendix 3, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Discussion

Our findings confirm the role of ulcerative STIs and highlight the contribution of non-ulcerative STIs and non-specific genital inflammation in HIV transmission risk in both donor and recipient in both M+F- and F+M- couples. The high PAF contributed by BIA merits further investigation. Genital practices may be a contributing factor and should be investigated.

As in other studies,40,47 ulcerative STIs contributed to a substantial PAF of transmission in both men and women donors and women seroconverters. Most incident ulcers diagnoses were asymptomatic and detected during routine physical examinations or screening. Syphilis is common in Zambia,48 and routine RPR screening is inexpensive and does not require sophisticated laboratory equipment or electricity, and penicillin treatment is inexpensive with no documented resistance.27

We did not find prevalent HSV-2 antibody associated with HIV transmission in our analysis, but this is not surprising as only a minority of HSV-2 antibody-positive persons developed detectable ulcers. When RPR-negative ulcers were detected, they were generally assumed to be herpetic and treated with acyclovir when it became available. Though Phase III clinical trials of acyclovir for HSV-2 antibody-positivity have not decreased HIV risk,49–51 acyclovir treatment of visible ulcers in RPR- patients is still advisable. Men and women could be encouraged to examine external genitalia and seek treatment for visible ulcers.

Inflammatory STIs in HIV+ men were risk factors for women’s HIV acquisition. As with ulcers, many inflammatory STIs were asymptomatic – particularly in women who cannot inspect their internal genitalia – and were diagnosed during routine physical examination or screening. Many countries, including Zambia, rely on syndromic STI detection, an approach associated with reduced HIV incidence in neighbouring Tanzania.52 In contrast, mass population treatment of presumptive STI has not resulted in reduced HIV incidence in most settings.53 New diagnostics for gonorrhea, chlamydia and trichomonas may be useful in screening asymptomatic disease.54

Inflammation not due to STI included reported symptoms, visible abnormalities on genital examination, and/or diagnosed candida or BV. Non-STI inflammation in women was associated both transmission and acquisition. BIA contributed a surprisingly high PAF to transmission in both HIV+ and HIV- men and women. Lymphadenopathy is non-specific and typically as reaction to infection; HIV-associated lymphadenopathy can last 2-3 months.55 To develop testable interventions to reduce discharge and non-specific inflammation without compromising genital integrity, an understanding of current genital practices is needed. In Zambia, as in many sub-Saharan African countries, women engage in intra-vaginal practices in response to discharge, genital disturbance, or for cultural reasons, which can lead to inflammatory processes, abrasion and increased STI risk.56–58 Additionally, highly diverse non-lactobacillus-dominated bacterial communities have been associated with inflammation facilitating HIV transmission,59–61 and a better understanding of the microbiome is needed.62–64 Education ideally before initiation of sexual activity, to increase recognition and management of abnormal vaginal discharges, odours or discomfort, is indicated.

As expected, lack of circumcision was independently predictive of seroconversion in F+M- couples. BIA was not associated with increased risk of seroconversion in circumcised HIV- men. Being uncircumcised with smegma was associated with risk of both transmitting and acquiring HIV. The presence of smegma increased the risk associated with BIA. We support the scale-up targeted voluntary MC for HIV- men with HIV+ partners. In settings like Zambia where circumcision is not a tradition and MC is low, research on men’s genital hygiene practices is needed. Foreskin smegma has been associated with inguinal adenopathy in Rwandan men,65 and a study of Ugandan men found foreskin inflammation to be associated with higher VL and smegma.66

We observed a decrease in infections at the time of enrolment versus subsequent months, paralleling the reported onset of condom use after CVCT. These data suggest GUIs contribute a substantial proportion of new HIV infections in ART-naïve serodiscordant couples after CVCT. In Zambia, virological failure, transmitted resistance21,67,68 and GUI-associated transmission of multiple HIV-variants66,69,70 have been noted.

Limitations

We previously published analyses of possible selective enrolment and retention biases which may limit generalizability.71 A possible selection bias for healthier index partners and information bias in self-reported exposure variables could be differential by risk, biasing our results in an unknown direction. It is possible that couples with GUIs were more likely to have follow-up visits, though baseline STIs were not associated with retention.71 Though we attempt to control for unprotected sex to assess the independent effect of genital inflammation, uncontrolled confounding could make the latter a proxy measure of unprotected sex.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm the role of STIs and highlight the contribution of non-specific genital inflammation to HIV transmission and acquisition risk in both HIV+ and HIV- men and women. A multipronged approach will be needed that maximizes detection, management and prevention. More research to develop low-cost, sustainable interventions to reduce genital co-factors for HIV transmission is warranted.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the study couples and staff in Zambia who made this study possible. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author Contributions

K.M.W. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. B.V. contributed to the conception and design of the study, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. S.L. contributed to the conception and design of the study, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. R.C. contributed to the conception and design of the study, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. W.K. contributed to the conception and design of the study, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. L.H. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. N.H.K. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. I.B. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. C.V. contributed to the conception and design of the study, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. L.M. contributed to the conception and design of the study, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. E.C. contributed to the conception and design of the study, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. J.M. contributed to the conception and design of the study, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. A.T. contributed to the study conception and design, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. S.A. contributed to the study design and conception, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of interest: The authors do not have a commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

Key Messages

Observational research implicates several sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (including Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis, Treponema pallidum and herpes simplex virus 2), primarily as co-factors in HIV acquisition in high-risk women.

Studies considering the risk conferred by more common genital inflammatory conditions not due to STI are lacking.

Our findings confirm the contribution of STI and highlight the independent contribution of non-STI inflammatory processes to risk of HIV transmission and acquisition in both men and women.

Low self-reporting of symptoms of STIs supports routine screening/treatment where possible.

Studies to characterize pathogenesis of non-specific inflammation leading to development of interventions to reduce HIV transmission are warranted.

Funding

This work was supported by: the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD R01 HD40125); the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH R01 66767); the AIDS International Training and Research Program Fogarty International Center (D43 TW001042); the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409); the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID R01 AI51231; NIAID R01 AI040951; NIAID R01 AI023980; NIAID R01 AI64060; NIAID R37 AI51231); the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5U2GPS000758); and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative. This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Laga M, Manoka A, Kivuvu M a.. Non-ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases as risk factors for HIV-1 transmission in women: results from a cohort study. AIDS 1993;7:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ. et al. Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet 1989;2:403–07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW. et al. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis 1991;163:233–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mayer KH, Venkatesh KK.. Interactions of HIV, other sexually transmitted diseases, and genital tract inflammation facilitating local pathogen transmission and acquisition. Am J Reprod Immunol 2011;65:308–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ward H, Ronn M.. Contribution of sexually transmitted infections to the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010;5:305–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van de Wijgert J, Morrison C, Salata R, Padian N.. Is vaginal washing associated with increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition? AIDS 2006;20:1347–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van de Wijgert JH, Morrison CS, Brown J. et al. Disentangling contributions of reproductive tract infections to HIV acquisition in African Women. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen CR, Lingappa JR, Baeten JM. et al. Bacterial vaginosis associated with increased risk of female-to-male HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort analysis among African couples. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Masese L, Baeten JM, Richardson BA. et al. Changes in the contribution of genital tract infections to HIV acquisition among Kenyan high-risk women from 1993 to 2012. AIDS 2015;29:1077–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Homans J, Christensen S, Stiller T. et al. Permissive and protective factors associated with presence, level, and longitudinal pattern of cervicovaginal HIV shedding. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60:99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Passmore JA, Jaspan HB, Masson L.. Genital inflammation, immune activation and risk of sexual HIV acquisition. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016;11:156–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Masson L, Passmore JA, Liebenberg LJ. et al. Genital inflammation and the risk of HIV acquisition in women. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:260–09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Masson L, Arnold KB, Little F. et al. Inflammatory cytokine biomarkers to identify women with asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis who are at high risk of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect 2016;92:186–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esra RT, Olivier AJ, Passmore JA, Jaspan HB, Harryparsad R, Gray CM.. Does HIV Exploit the Inflammatory Milieu of the Male Genital Tract for Successful Infection? Front Immunol 2016;7:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pellett Madan R, Masson L, Tugetman J. et al. Innate Antibacterial Activity in Female Genital Tract Secretions Is Associated with Increased Risk of HIV Acquisition. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015;31:1153–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pellett Madan R, Dezzutti CS, Rabe L. et al. Soluble Immune Mediators and Vaginal Bacteria Impact Innate Genital Mucosal Antimicrobial Activity in Young Women. Am J Reprod Immunol 2015;74:323–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M. et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ondoa P, Gautam R, Rusine J. et al. Twelve-Month Antiretroviral Therapy Suppresses Plasma and Genital Viral Loads but Fails to Alter Genital Levels of Cytokines, in a Cohort of HIV-Infected Rwandan Women. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Denison JA, Koole O, Tsui S. et al. Incomplete adherence among treatment-experienced adults on antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. AIDS 2015;29:361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koole O, Tsui S, Wabwire-Mangen F. et al. Retention and risk factors for attrition among adults in antiretroviral treatment programmes in Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:1397–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chi BH, Cantrell RA, Zulu I. et al. Adherence to first-line antiretroviral therapy affects non-virologic outcomes among patients on treatment for more than 12 months in Lusaka, Zambia. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:746–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keiser O, Chi BH, Gsponer T. et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral treatment in programmes with and without routine viral load monitoring in Southern Africa. AIDS 2011;25:1761–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allen S, Karita E, Chomba E. et al. Promotion of couples' voluntary counselling and testing for HIV through influential networks in two African capital cities. BMC Public Health 2007;7:349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wall KM, Kilembe W, Nizam A. et al. Promotion of couples' voluntary HIV counselling and testing in Lusaka, Zambia by influence network leaders and agents. BMJ Open 2012;2. PMID: 22956641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Therapy for Hiv Infection in Adults and Adolescents. Geneva: WHO, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M. et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS 2003;17:733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dionne-Odom J, Karita E, Kilembe W. et al. Syphilis treatment response among HIV-discordant couples in Zambia and Rwanda. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:1829–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK.. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med 1983;74:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL.. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol 1991;29:297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lifson AR, Allen S, Wolf W. et al. Classification of HIV infection and disease in women from Rwanda. Evaluation of the World Health Organization HIV staging system and recommended modifications. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:262–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peters PJ, Zulu I, Kancheya NG. et al. Modified Kigali combined staging predicts risk of mortality in HIV-infected adults in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2008;24:919–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fideli US, Allen SA, Musonda R. et al. Virologic and immunologic determinants of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2001;17:901–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boeras DI, Luisi N, Karita E. et al. Indeterminate and discrepant rapid HIV test results in couples' HIV testing and counselling centres in Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2011;14:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trask SA, Derdeyn CA, Fideli U. et al. Molecular epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in a heterosexual cohort of discordant couples in Zambia. J Virol 2002;76:397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eshleman SH, Hudelson SE, Bruce R. et al. Analysis of HIV type 1 gp41 sequences in diverse HIV type 1 strains. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2007;23:1593–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Greenland S. Bias in methods for deriving standardized morbidity ratio and attributable fraction estimates. Stat Med 1984;3:131–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Levin ML. The occurrence of lung cancer in man. Acta Unio Int Contra Cancrum 1953;9:531–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miettinen OS. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol 1974;99:325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ashraf S, Huque MH, Kenah E, Agboatwalla M, Luby SP.. Effect of recent diarrhoeal episodes on risk of pneumonia in children under the age of 5 years in Karachi, Pakistan. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Benichou J. A review of adjusted estimators of attributable risk. Stat Methods Med Res 2001;10:195–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benichou J. [ Biostatistics and epidemiology: measuring the risk attributable to an environmental or genetic factor.] Comptes Rendus Biol 2007;330:281–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Newcombe RG. Re: "Confidence limits made easy: interval estimation using a substitution method". Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:884–85; author reply 885-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Greenland S. Re: "Confidence limits made easy: interval estimation using a substitution method". Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:884; author reply 885-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee KJ, Carlin JB.. Multiple imputation for missing data: fully conditional specification versus multivariate normal imputation. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:624–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Demirtas H, Freels SA, Yucel RM.. Plausibility of multivariate normality assumption when multiply imputing non-gaussian continuous outcomes: a simulation assessment. J Stat Comput Simulation 2008;78:69–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Boily MC, Baggaley RF, Wang L. et al. Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2009;9:118–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E. et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet 2008;371:2183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Celum C, Wald A, Hughes J. et al. Effect of aciclovir on HIV-1 acquisition in herpes simplex virus 2 seropositive women and men who have sex with men: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:2109–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Celum C, Wald A, Lingappa JR. et al. Acyclovir and transmission of HIV-1 from persons infected with HIV-1 and HSV-2. N Engl J Med 2010;362:427–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M. et al. Effect of herpes simplex suppression on incidence of HIV among women in Tanzania. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1560–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J. et al. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1995;346:530–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stillwaggon E, Sawers L.. Rush to judgment: the STI-treatment trials and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:19844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Herbst de Cortina S, Bristow CC, Joseph Davey D, Klausner JD.. A Systematic Review of Point of Care Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2016;2016:4386127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mohseni S, Shojaiefard A, Khorgami Z, Alinejad S, Ghorbani A, Ghafouri A.. Peripheral lymphadenopathy: approach and diagnostic tools. Iran J Med Sci 2014;39(Suppl 2):158–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Alcaide ML, Chisembele M, Malupande E, Arheart K, Fischl M, Jones DL.. A cross-sectional study of bacterial vaginosis, intravaginal practices and HIV genital shedding; implications for HIV transmission and women's health. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alcaide ML, Cook R, Chisembele M, Malupande E, Jones DL.. Determinants of intravaginal practices among HIV-infected women in Zambia using conjoint analysis. Int J STD AIDS 2016;27:453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alcaide ML, Chisembele M, Mumbi M, Malupande E, Jones D.. Examining targets for HIV prevention: intravaginal practices in Urban Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014;28:121–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Borgdorff H, Tsivtsivadze E, Verhelst R. et al. Lactobacillus-dominated cervicovaginal microbiota associated with reduced HIV/STI prevalence and genital HIV viral load in African women. ISME J 2014;8:1781–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gautam R, Borgdorff H, Jespers V. et al. Correlates of the molecular vaginal microbiota composition of African women. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Anahtar MN, Byrne EH, Doherty KE. et al. Cervicovaginal bacteria are a major modulator of host inflammatory responses in the female genital tract. Immunity 2015;42(5):965–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Robinson CK, Brotman RM, Ravel J.. Intricacies of assessing the human microbiome in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol 2016;26:311–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. van de Wijgert JH, Borgdorff H, Verhelst R. et al. The vaginal microbiota: what have we learned after a decade of molecular characterization? PloS One 2014;9:e105998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. van de Wijgert JH, Jespers V.. Incorporating microbiota data into epidemiologic models: examples from vaginal microbiota research. Ann Epidemiol 2016;26:360–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Seed J, Allen S, Mertens T. et al. Male circumcision, sexually transmitted disease, and risk of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1995;8:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Haaland RE, Hawkins PA, Salazar-Gonzalez J. et al. Inflammatory genital infections mitigate a severe genetic bottleneck in heterosexual transmission of subtype A and C HIV-1. PLoS Pathogens 2009;5:e1000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Price MA, Wallis CL, Lakhi S. et al. Transmitted HIV type 1 drug resistance among individuals with recent HIV infection in East and Southern Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27:5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Elema R, Mills C, Yun O, Lokuge K. et al. Outcomes of a remote, decentralized health center-based HIV/AIDS antiretroviral program in Zambia, 2003 to 2007. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic ILL) 2009;8:60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Boeras DI, Hraber PT, Hurlston M. et al. Role of donor genital tract HIV-1 diversity in the transmission bottleneck. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:E1156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Carlson JM, Schaefer M, Monaco DC. et al. HIV transmission. Selection bias at the heterosexual HIV-1 transmission bottleneck. Science 2014;345:1254031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kempf MC, Allen S, Zulu I. et al. Enrollment and retention of HIV discordant couples in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;4:116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.