ABSTRACT

Background: Immunoglobulin M (IgM) nephropathy is an idiopathic glomerulonephritis characterized by diffuse mesangial deposition of IgM. IgM nephropathy has been a controversial diagnosis since it was first reported, and there are few data identifying specific pathological features that predict the risk of progression of renal disease.

Methods: We identified 57 cases of IgM nephropathy among 3220 adults undergoing renal biopsy at our institution. Biopsies had to satisfy the following three criteria to meet the definition of IgM nephropathy in this study: (i) dominant mesangial staining for IgM, (ii) mesangial deposits on electron microscopy (EM) and (iii) exclusion of systemic disease.

Results: The median age was 42 years and 24 patients were male. Thirty-nine per cent of patients presented with the nephrotic syndrome, 49% presented with non-nephrotic proteinuria and 39% had eGFR <60 mL/min. The median post-biopsy follow-up was 40 months and serum creatinine had doubled in 31% by 5 years. Of histological parameters, glomerular sclerosis and tubular atrophy, but not mesangial proliferation, were risk factors for renal insufficiency. Thirty-nine per cent of nephrotic patients achieved complete remission, and outcome was significantly worse in those who did not respond to treatment. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis was diagnosed in 80% of those undergoing repeat renal biopsy, despite ongoing mesangial IgM deposition.

Conclusions: We propose criteria for a consensus definition of IgM nephropathy.

Keywords: glomerulonephritis, immunoglobulin M, nephrotic syndrome, outcome, renal biopsy

INTRODUCTION

The existence of immunoglobulin M nephropathy (IgMN) as a distinct clinical entity has been controversial since its first description in the 1970s. Initial reports linked diffuse mesangial deposition of immunoglobulin M (IgM) with both haematuria [1, 2] and nephrotic syndrome [3, 4]. This condition was characterized by diffuse deposition of solely or mainly IgM in mesangial regions, with associated mesangial proliferation and mesangial electron dense deposits on electron microscopy (EM) (Figure 1). However, there remains no consensus definition for the diagnosis of IgMN with respect to the intensity of IgM staining, the presence of other immunoreactants, the degree of mesangial proliferation or the findings on EM [3, 5–10].

FIGURE 1.

Histological features of IgM nephropathy. (A) Granular immunoperoxidase staining for IgM immune complexes distributed throughout the glomerular mesangium. (B) Haematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrating expansion of mesangial matrix with mesangial hypercellularity (arrows). (C) Electron microscopy showing the presence of large mesangial dense deposits (arrow).

IgMN has been proposed to occupy a clinical position between minimal change disease (MCD) and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) [6]. At one end of the spectrum, the presence of mesangial IgM deposition has been associated with a higher rate of steroid resistance than MCD alone [6, 11, 12]. At the other, the evolution of IgMN to FSGS on repeat biopsy highlights a subgroup with worse prognosis [13–15]. In common with FSGS, IgMN has been reported to recur in renal transplant recipients [16, 17].

There has been considerable debate regarding the significance of mesangial IgM deposition in glomerulonephritis [12, 18, 19]. However, it is clear that there are clinical implications to mesangial proliferation with isolated deposition of other immunoreactants—IgA, C3, or C1q [20–23]. Moreover, while little is known of the underlying mechanism of IgM nephropathy, there is evidence that abnormalities in circulating IgM may play a role [7, 10, 24, 25], as has been hypothesized for IgA nephropathy [26, 27].

IgMN is by definition a pathological diagnosis, and previous studies have shown wide variations in the prevalence [28]. In the absence of autopsy data, the largest retrospective series of unselected biopsies suggest the prevalence is 2–5% [15, 29–31]. Some smaller series have included only nephrotic patients [12, 14], and it is clear that institutional criteria for renal biopsy will have a significant impact on the demographics of patients with this condition [28]. Moreover, both EM and immunohistochemistry can present technical challenges that may result in underdiagnosis. Some studies suggest that female gender and presentation with haematuria have a better prognosis [15, 32], implicating additional genetic and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of this condition.

There are few long-term studies of IgMN. The majority of patients with IgMN present with nephrotic syndrome, and consequently most studies have examined the response to steroid therapy [4, 6, 8, 9, 12–14, 29, 32]. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) has occurred in up to 25% of those followed up to 15 years [13, 15], although this may reflect a positive selection bias to follow-up. There is now anecdotal evidence of the efficacy of rituximab in IgMN [17, 25], and it is possible that the adoption of this or other immunosuppressive agents may improve the outcome of this condition.

It is clear that there exists an immunohistochemically distinct group of patients with dominant mesangial IgM deposition who do not fulfil established criteria for MCD or FSGS. This study attempts to describe the natural history and prognostic indicators of IgMN in adults at a single centre in Western Europe. It is hoped that the current study will allow a consensus definition of IgMN, such as has been applied to IgA nephropathy [20, 33].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective review of all adult native biopsies performed at the Imperial College Renal and Transplant Centre (London, UK) from 2006 to 2014. Biopsies had to satisfy the following three criteria to meet the definition of IgM nephropathy in this study. (i) There must be dominant staining for IgM in glomeruli by immunofluorescence or immunoperoxidase. The intensity of IgM staining (graded on a semi-quantitative scale) should be more than trace [34, 35]. The distribution of IgM staining should include presence in the mesangium, with or without capillary loop staining. IgA and IgG may be present but not in equal or greater intensity than IgM. Complement 3 (C3) and C1q may both be present. (ii) There had to be definite mesangial deposits on EM. (iii) We excluded all patients with systemic disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, paraproteinaemia) as described by Myllymäki et al. [15]. Demographic findings are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical findings in 57 patients with IgM nephropathy at the time of biopsy

| Demographics | Nephrotic syndrome | Non-nephrotic proteinuria | Total | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 22 | 35 | 57 | |

| Age (years), median (range) | 40 (17–78) | 41 (16–80) | 40 (19–80) | 0.58 |

| Gender, n | ||||

| Male | 9 | 15 | 24 | 0.88 |

| Female | 13 | 20 | 33 | |

| Ethnicity, n | ||||

| Caucasian | 13 | 15 | 28 | 0.43 |

| Afro-Caribbean | 5 | 9 | 14 | |

| South Asian | 4 | 11 | 15 | |

| Creatinine at biopsy (µmol/L), median (range) | 107 (45–763) | 93 (42–433) | 95 (42–763) | 0.14 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min, n | 11 | 1 | 22 | |

| Albumin (g/L), median (range) | 21 (10–29) | 35 (24–42) | 30 (10–42) | <0.001 |

| Urine protein:creatinine ratio, median (range) | 670 (363–1671) | 150 (47–520) | 297 (47–1671) | <0.001 |

Diagnostic definitions

Nephrotic syndrome was defined as a urine protein:creatinine ratio >300 mg/mmol along with serum albumin <30 g/L. The primary renal outcome was defined as a doubling of the serum creatinine from the time of biopsy. Post-biopsy follow-up is defined as the time from the diagnosis of IgM nephropathy to the last documented clinic visit.

Response to therapy

The primary end point in this study was the doubling of serum creatinine from the level at the time of renal biopsy. For those patients with nephrotic syndrome, partial remission (PR) was defined as proteinuria ≤50% baseline and complete remission (CR) as normal serum albumin with a urine protein:creatinine ratio <50 mg/mmol.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of median and standard deviation or range were used for continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. Fisher's exact and Student's t-tests were used to compare means between independent groups. Correlation between clinical and pathological features was assessed by the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) and Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon tests. GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Of 3220 biopsy specimens with primary glomerular disease during the period 2006–14, 57 met the criteria for IgM nephropathy (1.8%). Patients were followed up for a median of 46 months (range 0.2–113). Their demographic, clinical and laboratory findings at the time of presentation are shown in Table 1. The median age for this cohort was 42 years (range 17–80). Twenty-four were male, giving a male:female ratio of 1:1.4. Twenty-six patients (45.6%) presented with non-nephrotic proteinuria, while only 22 (38.6%) presented with nephrotic syndrome. Of the remainder, six (10.5%) patients presented with haematuria and three (5.3%) were biopsied primarily for deteriorating renal function. The median serum creatinine was 94 (42–763) µmol/L and 22 (38.6%) patients had an eGFR <60 mL/min.

Immunopathological findings

The detailed morphological, immunofluorescence and electron microscopy (EM) findings are listed in Table 2. The mean number of glomeruli examined by light microscopy was 15.3 ± 7.8, while 2.7 ± 1.5 were examined by EM. The most common morphological change consisted of segmental sclerotic lesions, affecting 40 (70.2%) biopsies to some degree, although only 40% of cases had >20% affected glomeruli. All cases with segmental sclerosis showed diffuse mesangial positivity, in contrast to the non-specific segmental trapping of IgM seen in idiopathic FSGS [31].

Table 2.

Summary of pathological findings

| Region | Characteristic | Value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Glomeruli | Mean number examined | 15.3 ± 7.8 |

| Normal or minimal lesions | 13 (22.8) | |

| Segmental sclerosis | 40 (70.2) | |

| Mesangium | Hypercellularity | 17 (29.8) |

| Increased matrix | 22 (38.6) | |

| Tubules and interstitium | Interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy | 42 (73.4) |

| Immunofluorescence/ immunoperoxidase | Any other immunoglobulin | 4 (7.0) |

| C3 | 29 (50.9) | |

| C1q | 30 (52.6) | |

| Electron microscopy | Segmental epithelial foot process effacement | 22 (38.6) |

| Mesangial expansion | 40 (70.2) |

Mesangial changes, including mesangial hypercellularity (29.8%) and increased mesangial matrix (38.6%) affected less than half of all biopsies. There was no endocapillary hypercellularity. Minor glomerular alterations were seen by light microscopy in 13 (22.8%) patients. Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis were seen in 44 (77.2%) biopsies. These chronic changes were of variable severity and affected on average 19 ± 19% of the tissue examined.

There was diffuse mesangial positivity of IgM in all cases. Twenty-four (42.1%) samples were examined by immunofluorescence, while the remainder were examined by immunoperoxidase microscopy. The intensity of staining was 1+ in 37 (64.9%), 2+ in 18 (31.6%) and 3+ in 2 (3.5%) biopsies. Four (7.0%) biopsies exhibited staining for other immunoglobulins, including IgA in two (3.5%) and IgG in two (3.5%). Complement components C3c and C1q were found in 29 (50.9%) and 30 (52.6%) biopsies, respectively.

EM was performed on all biopsies and revealed foot process effacement of epithelial cells in all cases. Epithelial foot process effacement was segmental in 22 (38.6%) biopsies and widespread/global in the remainder. Forty (70.2%) showed evidence of an increase in mesangial matrix. By definition, all biopsies showed mesangial electron dense deposits. Five (13.1%) biopsies showed evidence of scanty electron dense deposits in other regions, including subendothelial in four (7.0%) and subepithelial in one (1.8).

Clinical progression

Patients were followed up for a median of 40 months (range 1–113). At the time of renal biopsy, 22 (38.6%) patients had an eGFR <60 mL/min. Sixteen (28.1%) patients reached the primary end point in this study, namely the doubling of serum creatinine from baseline at the time of renal biopsy. By the end of this study, seven (12.3%) patients reached ESRD, of whom five (8.8%) received a renal transplant. There was no evidence of recurrent disease in any post-transplant biopsy.

Treatment response

All patients received standard therapy with maximum tolerated ACE inhibitors ± angiotensin II receptor blockers. Each patient's nephrologist then selected adjuvant therapy. In total, 22 (38.6%) patients received immunosuppression of any kind, including prednisolone in 11 (19.3%), tacrolimus in 10 (17.5%), mycophenolate mofetil in 3 (5.3%), rituximab in 3 (5.3%), and cyclophosphamide in 1 (1.6%). There was no significant difference in progression to doubling of serum creatinine between those patients treated with any kind of immunosuppression and those who were not.

Of 23 patients presenting with nephrotic syndrome, 14 (60.9%) achieved PR after a mean of 160 days (range 27–771), while nine (39.1%) achieved CR after a mean of 93 days (range 36–226). Renal outcome was significantly better (P < 0.005) in those who achieved CR compared with those who did not. Two of the nine patients who achieved CR subsequently had a relapse of their nephrotic syndrome.

Repeated renal biopsy

Ten (17.5%) patients underwent a second renal biopsy after a mean of 2.1 ± 1.8 years, as shown in Table 3. The second renal biopsy was indicated for relapse of nephrotic syndrome in three patients, for proteinuria in one, for treatment resistance in four, for deteriorating renal function in two and to facilitate withdrawal of prednisolone therapy in one. It is notable that all repeat biopsies retained mesangial positivity for IgM; however, only one showed IgM nephropathy by the current definition, with mesangial electron dense deposits on EM.

Table 3.

Clinical and histological features of those undergoing a repeated renal biopsy

| Patient no. | Sex | Age (years) | Time to rebiopsy | Indication | IgM stain | Mesangial EDD | Treatment | Rebiopsy finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 41 | 4.5 | Cr up | 1+ | N/A | Prednisolone | FSGS |

| 2 | F | 33 | 4.1 | Cr up | 1+ | N | None | FSGS |

| 3 | M | 20 | 2.0 | Nephrotic | 1+ | Y | None | IgMN |

| 4 | F | 59 | 0.6 | Nephrotic | 1+ | N | Tacrolimus, prednisolone | MCD |

| 5 | F | 54 | 3.1 | Partial relapse | 2+ | N | Tacrolimus, rituximab | FSGS |

| 6 | F | 45 | 4.6 | Proteinuria | 1+ | N | None | FSGS |

| 7 | M | 42 | 1.2 | Steroid resistant | 2+ | N/A | Prednisolone | FSGS |

| 8 | F | 19 | 0.4 | Steroid resistant | 1+ | N | Prednisolone, rituximab | FSGS |

| 9 | M | 41 | 0.1 | Steroid resistant | 2+ | N/A | Prednisolone | FSGS |

| 10 | M | 43 | 0.6 | Tacrolimus resistant | 1+ | N | Tacrolimus | FSGS |

Cr, creatinine; ; EDD, electron dense deposits; N/A, not available; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; IgMN, IgM nephropathy; MCD, minimal change in disease.

Prognostic factors

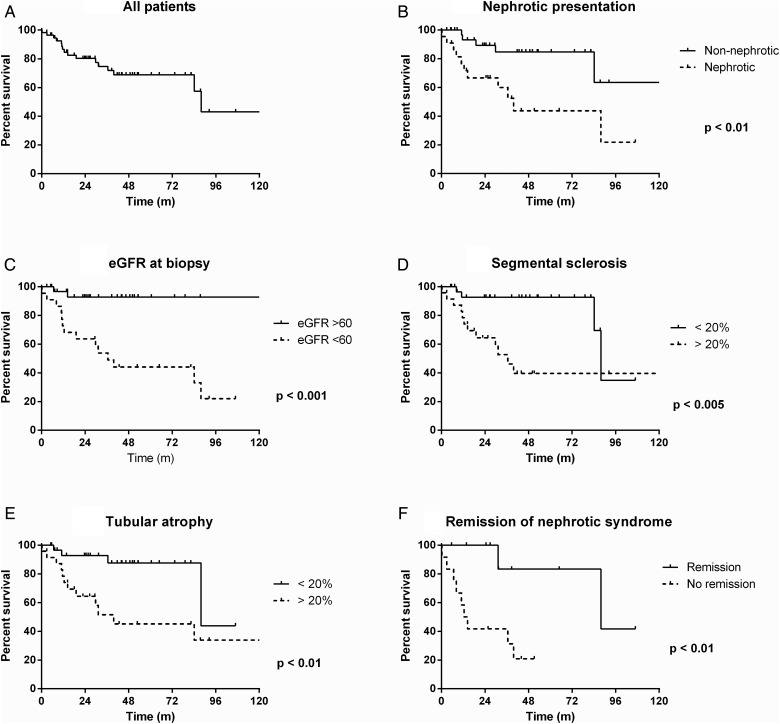

Figure 2 shows that 30% of patients with IgM nephropathy doubled their serum creatinine at 60 months. There was no significant effect of gender or ethnicity on preservation of renal function. Presentation with eGFR <60 mL/min (P < 0.001) and with nephrotic syndrome (P < 0.05) were significantly associated with subsequent renal impairment.

FIGURE 2.

Ten-year renal survival curves to doubling serum creatinine from baseline at time of biopsy in the IgM nephropathy cohort (n = 57). (A) Serum creatinine doubled in 25% of all patients by 3 years, 30% by 5 years and 57% by 10 years. Features at presentation, including (B) nephrotic syndrome and (C) estimated GFR (eGFR) <60 mL/min, were significantly associated with worse renal prognosis. Histological features in the biopsy associated with worse renal outcome included (D) >20% glomeruli with segmental sclerotic lesions and (E) >20% overall tubular atrophy. (F) Remission of nephrotic syndrome was associated with a better renal prognosis in those presenting with nephrotic syndrome.

The histological feature most strongly associated with progressive renal impairment was segmental sclerosis affecting >20% of glomeruli (P < 0.005). Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy affecting >20% of the biopsy area was also associated (P < 0.05) with renal impairment. However, neither mesangial cell proliferation nor mesangial expansion by excess matrix was associated with the doubling of serum creatinine. It is notable that neither the intensity of IgM staining nor the coexistence of staining for IgA, IgG, C3 or C1q had any influence on prognosis. Electron micrographic features, including the presence of increased mesangial matrix and the degree of epithelial foot process effacement (global versus segmental) were not associated with worse prognosis.

DISCUSSION

There have been a number of small clinicopathological studies of IgM nephropathy [13, 15, 28], but the majority have not applied rigid diagnostic criteria and have included children in the analysis. These series have examined mostly patients presenting with nephrotic syndrome and have suggested a poor response to steroids, with progressive renal failure in a minority. The first descriptions of IgM nephropathy suggested a disorder with a clinical course intermediate between that of MCD and FSGS [6]. This is one of the largest series of cases in the literature and presents a number of differences from previously reported studies.

Clinicopathological features

The prevalence of IgM nephropathy reported here (1.8% of native biopsies) is at the lower end of the 2–18% reported in previous studies [3, 4, 28, 30]) and less than MCD (5.8%) or FSGS (12.8%) in adults at our institution. The mean age at presentation is notably older than that reported in many previous studies, which have suggested a peak incidence in childhood or adolescence [13]; however, few studies have collected data exclusively from adults. The gender and racial distribution reported here suggests that there is no difference in prevalence between these different groups.

The clinical presentation in all retrospective biopsy series will to some extent reflect the referral pattern and biopsy criteria of an institution. In contrast to previous reports, a minority of patients in this series presented with nephrotic syndrome and there were no presentations with isolated haematuria [6, 13, 15, 31, 36]. Local policy has been to biopsy adults with minor urinary abnormalities, and most patients in the current series presented with simple proteinuria.

The immunopathological characteristics of the renal biopsies in this series are broadly similar to those reported previously. Although the threshold for IgM positivity has varied between studies [6, 28], we defined IgM nephropathy as having more than trace staining for IgM, to reflect the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy [33]. In contrast to those series where mesangial proliferation by light microscopy was included as a defining feature of IgMN [13], this was seen in fewer than half of all patients in the current study. Moreover, there was no prognostic association with mesangial cell proliferation or mesangial increase by excess matrix as seen in previous studies [13]. There was also no association with staining for other immunoglobulins.

The incidence of both global and segmental sclerosis was higher in this series than in previous studies [13, 31, 37]. We included only cases with diffuse or global staining for IgM and evidence of electron dense deposits on EM, in order to exclude cases of idiopathic FSGS [36]. The severity of sclerotic lesions mirrors the extent of tubular atrophy in many, and may be a feature of the older age of this population [36], or it may reflect the duration of symptoms prior to biopsy, but this was not seen in other large series [13, 15, 28]. Given the prognostic importance of glomerular sclerosis and tubular atrophy in other conditions, it is possible that a weaker association with mesangial reaction to IgM deposition was masked in this study [13, 31].

A particular feature of the current series was that all biopsies were examined by EM. Previous studies have included a variable proportion with mesangial electron dense deposits [7–9, 16, 36], but we considered it to be essential for a diagnosis of IgMN. There was no prognostic association with mesangial expansion on EM, as for light microscopy. There was also no prognostic association with the extent of epithelial cell foot process effacement, despite the association with clinical nephrotic syndrome at presentation.

Natural history

Previous studies of IgM nephropathy have suggested a clinical course intermediate between MCD and FSGS. In the present study, actuarial creatinine doubling time at 3 and 5 years was 25 and 30%, respectively. Only seven patients reached ESRD, and in all cases initial biopsies showed evidence of >20% globally sclerosed glomeruli and tubular atrophy. One of these patients had no segmental lesions out of nine glomeruli sampled, but the remainder all had >20% glomeruli with segmental sclerotic lesions. However, it might be expected that the outcome of this series would be worse than previously reported [13, 15] since the population studied here was older, had a high proportion of patients with renal impairment at presentation and comprised biopsies with a higher degree of glomerular scarring and tubular atrophy.

Many investigators have suggested that IgM nephropathy converts to FSGS over the course of time [6, 14, 28]. Eight of ten patients undergoing repeat biopsy in this series developed FSGS, with disappearance of mesangial deposits on EM in all eight despite continued positivity for IgM, supporting the suggestion that IgM mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis progresses to focal glomerulosclerosis [38–41]. Those patients undergoing a repeat biopsy did not have a worse outcome, and there were no factors present at initial biopsy that could predict the need for repeat biopsy or the development of FSGS [15]. It is notable that four patients who were excluded from this study met criteria for IgM nephropathy at the first biopsy but subsequently developed an immune complex or anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated glomerulonephritis.

Response to treatment

Another feature of this series was the low proportion of patients presenting with the nephrotic syndrome. Twenty of the 23 patients with nephrotic syndrome received immunosuppressive treatment. Of the three who did not receive treatment, two had scarred biopsies that rapidly progressed to ESRD and one had active infection with hepatitis C. First-line treatment for nephrotic syndrome was tacrolimus in 10 patients and prednisolone in 9, followed by subsequent treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab or cyclophosphamide. Previously reported steroid response rates have varied considerably, with 28% mean steroid resistance [15]. In our series, 39% achieved CR, although two of these nine patients had a subsequent relapse. Nonetheless, as has been noted in cases with FSGS, renal outcome was significantly better (P < 0.01) in those who achieved CR compared with those who did not [42].

Limitations of the current study

The current study shows that only small numbers of adult patients are affected by IgM nephropathy when defined by detailed histological criteria. Moreover, these histological criteria depend on electron microscopy that can be difficult to perform outside well-equipped centres [28]. Our patients have been treated with a range of immunosuppressive medication, which precludes recommendations for the optimal treatment for this condition. With a larger patient group it would be interesting to compare the renal prognosis in IgM nephropathy with that in FSGS or MCD.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study confirms the heterogeneous nature of IgMN. We show that it affects all extremes of age, and that in an institution with a low threshold for renal biopsy, the most common presenting feature of IgMN in adults is non-nephrotic proteinuria. In common with previous studies of IgMN [13, 15], IgA nephropathy [20], FSGS [43] and other glomerular disorders, we show that renal prognosis is associated with renal scarring, whether glomerular sclerosis or tubular atrophy. However, there was no prognostic effect of mesangial proliferation or staining with additional immunoreactants. Thirty-nine per cent of nephrotic patients responded to treatment, and the outcome of those who did not respond was significantly worse. Renal survival was nearly 70% at 5 years. We hope the current study will allow researchers to move towards a consensus definition of IgMN.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

T.C. was a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Lecturer. We are grateful for support from the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. We thank the following clinical colleagues who helped care for the patients in the glomerulonephritis and vasculitis clinics: Drs J. Galliford and J. Levy, and Sisters Jane Owen and Nicola McKenna.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

REFERENCES

- 1. Van de Putte LB, de la Riviere GB, van Breda Vriesman PJ. Recurrent or persistent hematuria. Sign of mesangial immune-complex deposition. N Engl J Med 1974; 290: 1165–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pardo V, Berian MG, Levi DF et al. Benign primary hematuria. Clinicopathologic study of 65 patients. Am J Med 1979; 67: 817–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohen AH, Border WA, Glassock RJ. Nephrotic syndrome with glomerular mesangial IgM deposits. Lab Invest 1978; 38: 610–619 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhasin HK, Abuelo JG, Nayak R et al. Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. Lab Invest 1978; 39: 21–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Helin H, Mustonen J, Pasternack A et al. IgM-associated glomerulonephritis. Nephron 1982; 31: 11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Border WA. Distinguishing minimal-change disease from mesangial disorders. Kidney Int 1988; 34: 419–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cavallo T, Johnson MP. Immunopathologic study of minimal change glomerular disease with mesangial IgM deposits. Nephron 1981; 27: 281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hsu HC, Chen WY, Lin GJ et al. Clinical and immunopathologic study of mesangial IgM nephropathy: report of 41 cases. Histopathology 1984; 8: 435–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mampaso F, Gonsalo A, Teruel J et al. Mesangial deposits of IgM in patients with the nephrotic syndrome. Clin Nephrol 1981; 16: 230–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Disciullo SO, Abuelo JG, Moalli K et al. Circulating heavy IgM in IgM nephropathy. Clin Exp Immunol 1988; 73: 395–400 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tejani A, Phadke K, Nicastri A et al. Efficacy of cyclophosphamide in steroid-sensitive childhood nephrotic syndrome with different morphological lesions. Nephron 1985; 41: 170–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swartz SJ, Eldin KW, Hicks MJ et al. Minimal change disease with IgM+ immunofluorescence: a subtype of nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2009; 24: 1187–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Donoghue DJ, Lawler W, Hunt LP et al. IgM-associated primary diffuse mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis: natural history and prognostic indicators. Q J Med 1991; 79: 333–350 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zeis PM, Kavazarakis E, Nakopoulou L et al. Glomerulopathy with mesangial IgM deposits: long-term follow up of 64 children. Pediatr Int 2001; 43: 287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Myllymaki J, Saha H, Mustonen J et al. IgM nephropathy: clinical picture and long-term prognosis. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 41: 343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salmon AH, Kamel D, Mathieson PW. Recurrence of IgM nephropathy in a renal allograft. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19: 2650–2652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Westphal S, Hansson S, Mjörnstedt L et al. Early recurrence of nephrotic syndrome (immunoglobulin M nephropathy) after renal transplantation successfully treated with combinations of plasma exchanges, immunoglobulin, and rituximab. Transplant Proc 2006; 38: 2659–2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vilches AR, Turner DR, Cameron JS et al. Significance of mesangial IgM deposition in ‘minimal change’ nephrotic syndrome. Lab Invest 1982; 46: 10–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ji-Yun Y, Melvin T, Sibley R et al. No evidence for a specific role of IgM in mesangial proliferation of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int 1984; 25: 100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int 2009; 76: 534–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pickering MC, D'Agati VD, Nester CM et al. C3 glomerulopathy: consensus report. Kidney Int 2013; 84: 1079–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jennette JC, Hipp CG. C1q nephropathy: a distinct pathologic entity usually causing nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 1985; 6: 103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wenderfer SE, Swinford RD, Braun MC. C1q nephropathy in the pediatric population: pathology and pathogenesis. Pediatr Nephrol 2010; 25: 1385–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Border WA, Cohen AH. Role of immunoglobulin class in mediation of experimental mesangial glomerulonephritis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1983; 27: 187–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Betjes MG, Roodnat JI. Resolution of IgM nephropathy after rituximab treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 53: 1059–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mestecky J, Raska M, Julian BA et al. IgA nephropathy: molecular mechanisms of the disease. Annu Rev Pathol 2013; 8: 217–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wyatt RJ, Julian BA. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2402–2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mubarak M, Kazi JI. IgM nephropathy revisited. Nephrourol Mon 2012; 4: 603–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Little MA, Dorman A, Gill D et al. Mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with IgM deposition: clinical characteristics and outcome. Ren Fail 2000; 22: 445–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Singhai AM, Vanikar AV, Goplani KR et al. Immunoglobulin M nephropathy in adults and adolescents in India: a single-center study of natural history. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2011; 54: 3–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mubarak M. IgM nephropathy. Indian J Pediatr 2013; 80: 357–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saha H, Mustonen J, Pasternack A et al. Clinical follow-up of 54 patients with IgM-nephropathy. Am J Nephrol 1989; 9: 124–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roberts IS, Cook HT, Troyanov S et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int 2009; 76: 546–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chang A, Gibson IW, Cohen AH et al. A position paper on standardizing the nonneoplastic kidney biopsy report. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7: 1365–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sethi S, Haas M, Markowitz GS et al. Mayo Clinic/Renal Pathology Society consensus report on pathologic classification, diagnosis, and reporting of GN. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 27: 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lawler W, Williams G, Tarpey P et al. IgM associated primary diffuse mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Clin Pathol 1980; 33: 1029–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Myllyharju J, Kivirikko KI. Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet 2004; 20: 33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hirszel P, Yamase HT, Carney WR et al. Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with IgM deposits. Clinicopathologic analysis and evidence for morphologic transitions. Nephron 1984; 38: 100–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aubert J, Humair L, Chatelanat F et al. IgM-associated mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and focal and segmental hyalinosis with nephrotic syndrome. Am J Nephrol 1985; 5: 445–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bhuyan UN, Srivastava RN. Incidence and significance of IgM mesangial deposits in relapsing idiopathic nephrotic syndrome of childhood. Indian J Med Res 1987; 86: 53–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gonzalo A, Mampaso F, Gallego N et al. Clinical significance of IgM mesangial deposits in the nephrotic syndrome. Nephron 1985; 41: 246–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Korbet SM. Treatment of primary FSGS in adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 1769–1776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Korbet SM. Clinical picture and outcome of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14(Suppl 3): 68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]