Abstract

Aims

Studies suggest that people who work long hours are at increased risk of stroke, but the association of long working hours with atrial fibrillation, the most common cardiac arrhythmia and a risk factor for stroke, is unknown. We examined the risk of atrial fibrillation in individuals working long hours (≥55 per week) and those working standard 35–40 h/week.

Methods and results

In this prospective multi-cohort study from the Individual-Participant-Data Meta-analysis in Working Populations (IPD-Work) Consortium, the study population was 85 494 working men and women (mean age 43.4 years) with no recorded atrial fibrillation. Working hours were assessed at study baseline (1991–2004). Mean follow-up for incident atrial fibrillation was 10 years and cases were defined using data on electrocardiograms, hospital records, drug reimbursement registers, and death certificates. We identified 1061 new cases of atrial fibrillation (10-year cumulative incidence 12.4 per 1000). After adjustment for age, sex and socioeconomic status, individuals working long hours had a 1.4-fold increased risk of atrial fibrillation compared with those working standard hours (hazard ratio = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.13–1.80, P = 0.003). There was no significant heterogeneity between the cohort-specific effect estimates (I2 = 0%, P = 0.66) and the finding remained after excluding participants with coronary heart disease or stroke at baseline or during the follow-up (N = 2006, hazard ratio = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.05–1.76, P = 0.0180). Adjustment for potential confounding factors, such as obesity, risky alcohol use and high blood pressure, had little impact on this association.

Conclusion

Individuals who worked long hours were more likely to develop atrial fibrillation than those working standard hours.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation , Life stress , Risk factors , Cohort study

Background

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and contributes to the development of several adverse health outcomes, such as stroke, heart failure, and multi-infarct dementia.1–3 Cardiovascular and respiratory disease, hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy are risk factors for atrial fibrillation.2,4,5 Additionally, findings from observational studies have been used to suggest that maintaining a lifestyle that reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease—avoidance of obesity, smoking and heavy alcohol consumption—may also have a positive impact on rates of atrial fibrillation.6–8

Although the 2016 European Guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention acknowledges psychosocial stress at work as a potential risk factor for cardiovascular disease,9 citing evidence that show long working hours to be associated with increased stroke risk,10 little is known about the role of long working hours as a potential risk factor of atrial fibrillation. In principle, stress and long working hours may enhance functional re-entry, repetitive pulmonary vein and atrial firing,11,12 and autonomic nervous system abnormalities,13 inducing arrhythmia vulnerability.14 Thus, some studies have found that stress and ‘exhaustion’ predict symptomatic atrial fibrillation.15,16 However, this evidence is uncertain because it is based on small study samples. Accordingly, we conducted a large-scale study on long working hours and incident atrial fibrillation in the general population using data from cohort studies participating in the Individual-Participant-Data Meta-analysis in Working Populations (IPD-Work) Consortium.10,17,18

Methods

Participants

In ten cohort studies of the IPD-Work Consortium, data on working hours and atrial fibrillation were available, although in two studies (the Intervention Project on Absence and Well-being and the Work, Lipids and Fibrinogen study Norrland) the low number of participants with long working hours (n = 6 and 55, respectively) and atrial fibrillation during the follow-up (n = 0 among participants working long hours in both studies) precluded inclusion of these studies in the analysis. The remaining eight studies were included in the analyses: the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire Study (COPSOQ) I and COPSOQ-II, the Danish Work Environment Cohort Study (DWECS), the Finnish Public Sector Study (FPS), the Health and Social Support study (HeSSup), the PUMA study, the Whitehall II study, and the Work, Lipids and Fibrinogen study (WOLF), Stockholm (see Supplementary material online, Appendix S1). Most of these were multi-purpose studies designed to examine health effects across a range of risk factors, including those related to workplace. The analytic sample comprised 85 494 participants (29 579 men and 55 915 women) from the UK, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland who were free of atrial fibrillation at baseline (1991–2004). All studies were approved by the relevant local or national ethics committee and all participants gave informed consent to participate.

Assessment of working hours and covariates at baseline

Working hours were assessed at baseline which was between 1991 and 2004 depending on the cohort study. As in previous studies, we classified working hours into categories of ‘less than 35 h’, ‘35–40 h’, ‘41–48 h’, ‘49–54 h’, and ‘≥55 h/week’.10,17,18 The first category includes part-time workers and the second category is the reference group of full-time workers with standard working hours. The category of 41–48 h/week includes those working more than standard hours but still in accordance with the European Union Working Time Directive (2003/88/EC), which guarantees employees the right to limit weekly working time at 48 h on average. The remaining two categories include working times beyond this threshold, with the top category of 55 or more hours per week being the most commonly used definition for long working hours in medical research.10,17–20

Pre-defined, harmonized covariates included potential confounders, such as age, sex, and socioeconomic status (SES; high, intermediate, low, unknown), and potential mediators, such as smoking (current, ex, never smoker), body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight (in kilograms)/height (in meters) squared and categorized according to the WHO classification: <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, ≥35 kg/m2), physical activity (sedentary, moderately active, highly active), and alcohol consumption (non-use; moderate, women: 1–14 drinks/week, men: 1–21 drinks/week; intermediate, women: 15–20 drinks/week; men: 22–27 drinks/week; risky: women: 21 or more drinks/week, men: 28 or more drinks/week).

As ascertainment of atrial fibrillation in the Whitehall II study was by electrocardiogram (ECG), the gold standard method, and the study included the widest range of atrial fibrillation risk factors of all IPD-Work studies, a further set of analyses were undertaken in those data only. Additional non-cardiovascular and cardiovascular risk factors at baseline deemed to act as potential confounders or mediators of the long working hours-atrial fibrillation relationship included:5,21 Prevalent infection/high systemic inflammation defined using serum C-reactive protein (high-sensitivity immunonephelometric assay in a BN ProSpec nephelometer; values >10 mg/L); self-reported respiratory illness and doctor-diagnosed heart trouble (including valve disease and congestive heart failure); left ventricular hypertrophy (Minnesota codes 3-1, 3-3, 3-4); diabetes mellitus (defined as fasting glucose >7.0 mmol/L or a 2-h post load glucose >11.1 mmol/L during a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test, or self-reported doctor-diagnosed diabetes); depressive and anxiety symptoms using the General Health Questionnaire caseness;22 systolic blood pressure (the average of two readings taken in the sitting position after 5 min of rest with the Hawksley random-0 sphygmomanometer); use of antihypertensive medication; total and high-density-lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentrations (measured by automated enzymatic colorimetric methods).

To examine whether cardiovascular disease preceded or followed atrial fibrillation, we assessed coronary heart disease and stroke events at baseline and follow-up. Coronary heart disease was denoted by diagnostic codes I21–I22 in ICD-10, 410 in ICD-9 (in hospitalization data) or using the MONICA criteria (Whitehall II study clinical examination).23 Coronary death included diagnostic codes I20–I25 in ICD-10, 410–414 in ICD-9. Stroke included diagnostic codes I60, I61, I63, I64 in ICD-10 and 430, 431, 433, 434, 436 in ICD-9.

Outcome ascertainment

In WOLF, HeSSup, PUMA, FPS, DWECS, COPSOQ-I, and COPSOQ-II, cases of atrial fibrillation at baseline and follow-up were identified using electronic patient records of hospitalizations and deaths [International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) diagnostic codes I48 (ICD-10), 427.3 (ICD-9) or 427.4 (ICD-8)]. In FPS and HeSSup, atrial fibrillation cases were additionally identified from the nationwide drug reimbursement register for the treatment of this condition. In that register, entitlement to reimbursement is based on a detailed medical examination and predefined criteria for the diagnosis. In the Whitehall II study, atrial fibrillation was assessed using resting ECGs (Minnesota code 83x) at baseline in 1991 and at follow-up examinations in 1997, 2003, and 2008. In each study, participants with any indication of pre-existing atrial fibrillation in electronic health records or ECG at baseline were excluded (n = 250).

Statistical analysis

We analysed anonymized or pseudonymized individual-level data from each cohort. We studied the associations between long working hours and baseline covariates using logistic regression for dichotomous covariates (obesity, physical inactivity, current smoking, risky alcohol use, infection/high systemic inflammation, respiratory disease, heart trouble, left ventricular hypertrophy, diabetes, depressive and anxiety symptoms, antihypertensive medication) and analysis of variance for continuous covariates (systolic blood pressure, total, and HDL cholesterol) with adjustment for age (continuous variable), sex and SES (categorical variables). To examine the extent to which incident atrial fibrillation was due to pre-existing cardiovascular disease, we computed the proportion of incident atrial fibrillation cases who had a record of cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease or stroke) before atrial fibrillation was first recorded.

After confirming that the proportional hazards assumptions were not violated, we used Cox proportional hazards models to generate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for long working hours (55 h or more per week) compared with standard (35–40) working hours (reference) in predicting incident atrial fibrillation in participants free of this arrhythmia at baseline. In the basic statistical model, effect estimates were adjusted for age (continuous variable), sex, and SES (categorical variable) at baseline. Adjustment for SES is important because long working hours were more common in participants with high SES (6.9% worked long hours) relative to those in low SES group (4.6%). To examine whether the association between long working hours and atrial fibrillation was mediated by poor lifestyle factors, adjustments were made for smoking (never, ex-, current smoker), alcohol consumption (non-use, moderate, risky), BMI (categorical), and physical activity (inactive, moderately active, highly active) at baseline. In analyses carried out in the Whitehall II study, additional adjustments were made for doctor-diagnosed heart abnormalities, infection/high systemic inflammation, respiratory disease, heart problems, left ventricular hypertrophy, diabetes mellitus, depressive and anxiety symptoms, use of antihypertensive medication (all dichotomous variables), systolic blood pressure and total and HDL-cholesterol (continuous variables), all measured at baseline.

Meta-analysis, based on random-effects modelling, was used to combine results from each cohort. We examined heterogeneity of the cohort-specific estimates using the I2 statistic (a higher value indicating a greater degree of heterogeneity). In sensitivity analyses, we examined the association separately in men and women, by age group (<50 vs. >50 years at baseline) and by socioeconomic status (high, intermediate, low). We also stratified the analysis by the method of case ascertainment to examine whether the association between long working hours and atrial fibrillation was attenuated when the ascertainment was based on electronic health records from registers of hospital admissions, deaths and drug reimbursement as compared with ECG assessment.

The statistical software SAS (version 9.4) was used to analyse study-specific data and Stata (MP version 13.1) was used to compute the meta-analyses.

Results

Of the 85 494 participants, 35% were men and the mean age was 43.4 years (range 17–70) at baseline (Table 1). During the mean follow-up of 10.0 years, 1061 participants were diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (10-year cumulative incidence 12.4 per 1000). In 71.4% of cases, atrial fibrillation was diagnosed before the age of 65 (see Supplementary material online, Appendix S2). This is as expected given the young mean age and length of follow-up. Of the incident atrial fibrillation cases, 86.7% had no cardiovascular disease during the study period whereas 10.2% of incident cases of atrial fibrillation had pre-existing cardiovascular disease when atrial fibrillation was first recorded (see Supplementary material online, Appendix S3).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by atrial fibrillation status at follow-up

| All N = 85 494 | Incident cases N = 1061 | Non-cases N = 84 433 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| Mean | 43.4 | 51.6 | 43.3 |

| Range | (17–70) | (21–69) | (17–70) |

| Sex, N (%) | |||

| Men | 29 579 (34.5) | 678 (63.9) | 28 901 (34.2) |

| Women | 55 915 (65.5) | 383 (36.1) | 55 532 (65.8) |

| Socioeconomic status, N (%) | |||

| High | 22 555 (26.4) | 336 (31.7) | 22 219 (26.3) |

| Intermediate | 41 570 (48.6) | 432 (40.7) | 41 138 (48.7) |

| Low | 19 625 (23.0) | 279 (26.3) | 19 346 (22.9) |

| Unknown | 1744 (2.0) | 14 (1.3) | 1730 (2.0) |

| Country, N (%) | |||

| UK | 6649 (7.8) | 224 (21.1) | 6425 (7.6) |

| Denmark | 12 563 (14.7) | 161 (15.2) | 12 402 (14.7) |

| Sweden | 5551 (6.5) | 131 (12.3) | 5420 (6.4) |

| Finland | 60 731 (71.0) | 545 (51.4) | 60 186 (71.3) |

All participants were free of atrial fibrillation at study baseline.

A total of 4484 (5.2%) participants worked ≥55 h/week and 53 468 (62.5%) worked standard 35–40 hours at baseline. Long working hours were associated with a slightly poorer lifestyle profile at baseline characterized by a higher prevalence of obesity, leisure-time physical inactivity, smoking and risky alcohol use (Table 2, Supplementary material online, Appendix S4). Analysis of further baseline covariates in the Whitehall II study show that participants working long hours were more likely to have depressive and anxiety symptoms and less likely to have left ventricular hypertrophy than those working standard hours.

Table 2.

Differences in lifestyle, biological and psychological factors between individuals working long (≥55 h/week) and standard (35–40 h/week) working hours

| Working hours category |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristic | Long | Standard | ||

| IPD-Work cohortsa | Prevalence (%) | Odds ratiob (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Obese | 11.8 | 10.5 | 1.34 (1.17 to 1.54) | <0.0001 |

| Physically inactive | 21.7 | 19.1 | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.30) | 0.0007 |

| Smoking | 24.9 | 22.3 | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.31) | 0.026 |

| Risky alcohol use | 8.4 | 5.7 | 1.18 (1.04 to 1.33) | 0.0084 |

| Whitehall IIc | ||||

| Infection/high inflammation | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.26 (0.66 to 2.42) | 0.48 |

| Respiratory disease | 7.9 | 6.5 | 1.30 (0.91 to 1.84) | 0.15 |

| Heart trouble (incl. valve disease) | 7.4 | 7.9 | 0.88 (0.62 to 1.24) | 0.45 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 8.6 | 9.9 | 0.70 (0.50 to 0.96) | 0.028 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.4 | 2.6 | 0.74 (0.35 to 1.57) | 0.43 |

| Depressive and anxiety symptoms | 27.2 | 20.0 | 1.57 (1.27 to 1.95) | <0.0001 |

| Antihypertensive medication | 3.3 | 6.3 | 0.66 (0.40 to 1.08) | 0.10 |

| Unadjusted mean | Mean differencea (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 119.3 | 119.9 | −1.1 (−2.3 to 0.1) | 0.071 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 6.4 | 6.4 | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 0.49 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.4 | 1.4 | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 0.57 |

4486 participants with long working hours and 53 502 participants with standard working hours.

Odds ratios and mean differences for long compared with standard hours with risk factor as the outcome. Adjustment for age, sex and socioeconomic status.

584 participants with long working hours and 3016 participants with standard working hours.

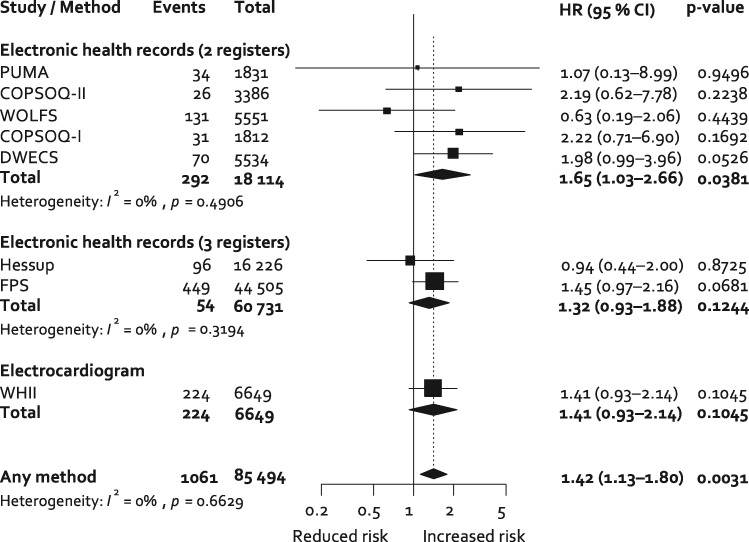

In age, sex and SES-adjusted analyses, participants working long hours were at increased risk of incident atrial fibrillation: the hazard ratio compared with those working standard hours is 1.42 (95% CI 1.13–1.80, P = 0.0031) (Figure 1). There was little heterogeneity in the cohort-specific estimates: I2 = 0%, P = 0.66. Additional adjustment for lifestyle factors marginally attenuated the association between long vs. standard working hours and incident atrial fibrillation (1.41, 95% CI 1.10–1.80, P = 0.0059, I2 = 0%, P = 0.62) (see Supplementary material online, Appendix S5). The association between long working hours and atrial fibrillation remained after adjustment for pre-existing coronary heart disease at the time of atrial fibrillation diagnosis (1.41, 95% CI 1.12–1.78, P = 0.0039) and excluding participants with cardiovascular disease at baseline (N = 549, hazard ratio 1.41, 95% CI 1.11–1.79, P = 0.0054) or cardiovascular disease at baseline or follow-up (N = 2006, hazard ratio = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.05–1.76, P = 0.0180).

Figure 1.

Random-effects meta-analysis of the association of long vs. standard working hours with incident atrial fibrillation adjusted for age, sex, and socioeconomic status. HR, hazard ratio.

As the Whitehall II study had available data on several other potential risk factors for atrial fibrillation, further adjustments were performed using data from this cohort. The hazard ratio for long vs. standard working hours as a predictor of incident atrial fibrillation was 1.41 (95% CI 0.93–2.14, P = 0.1045, N = 6649, 224 incident cases of atrial fibrillation) after adjustment for age, sex, and SES; this is close to that observed in the total population (Figure 1). Additional adjustment for lifestyle factors, infection/high systemic inflammation, respiratory disease, doctor-diagnosed heart trouble (including valve disease and congestive heart failure), left ventricular hypertrophy, diabetes mellitus, depressive and anxiety symptoms, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, total and HDL-cholesterol had little effect on this estimate (1.42, 95% CI 0.91–2.23, P = 0.12, N = 5867, 195 incident cases of atrial fibrillation).

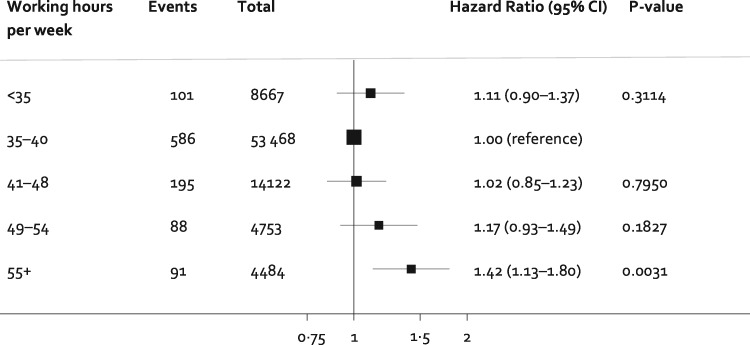

Figure 2 shows the shape of the association between all the categories of working hours and incident atrial fibrillation. There was a dose-response gradient with hazard ratios of 1.02, 1.17, and 1.42 for 41–48, 49–54 and ≥55 working hours per week compared with standard 35–40 working hours per week.

Figure 2.

Association of categories of weekly working hours with incident atrial fibrillation. Estimates are adjusted for age, sex, and socioeconomic status.

Sensitivity analysis

In meta-analysis stratified by method of ascertainment of atrial fibrillation (Figure 1), the age-, sex- and SES-adjusted hazard ratio for long working hours compared with standard working hours was 1.41, 95% CI 0.93–2.14, P = 0.105, for the one study using electrocardiogram, 1.32, 95% CI 0.93–1.88, P = 0.124, for the two studies using records from hospital admissions, death and drug reimbursements, and 1.65, 95% CI 1.03–2.66, P = 0.038, for the five studies using records from hospital admissions and deaths only. In stratified analyses, the association between long working hours and atrial fibrillation did not differ between men and women (P = 0.267), participants younger than 50 and those 50 years or older at baseline (P = 0.704) or by socioeconomic group (P = 0.186).

Discussion

It was found in this multi-cohort study of 85 494 men and women that those working 55 h or more a week had an approximately 40% higher risk of atrial fibrillation compared with those working a standard 35–40-h week. Nine out of ten incident atrial fibrillation cases occurred among those free of pre-existing or concurrent cardiovascular disease, suggesting that the observed excess risk of atrial fibrillation is likely to reflect the effect of long working hours rather than the effect of pre-existing or concurrent cardiovascular disease. Multivariable adjusted analyses showed that the association was not attributable to socioeconomic circumstances, lifestyles or common risk factors for atrial fibrillation. In combination, these findings suggest that long working hours is a risk factor for atrial fibrillation.

We are not aware of other studies on long working hours and atrial fibrillation, although our investigation is in agreement with small-scale studies linking other work-related stressors, such as job strain, to this condition.24,25 The mechanisms underlying the association between long working hours and atrial fibrillation are not known. A recent systematic review of observational evidence from over 20 million men and women found that obesity, smoking, hypertension, and high systemic inflammation were associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation, whereas evidence on cholesterol and physical activity was inconsistent.21 Other studies have also suggested that high alcohol consumption and obesity-related conditions, such as sleep apnea, may have a role in the aetiology of atrial fibrillation.26,27 In the present study, the prevalence of obesity, smoking, physical inactivity and high alcohol consumption was higher in individuals working long hours than in the standard working hours group, but the difference was small (<3 percentage points). Similarly, there appeared to be no difference in systemic inflammation, systolic blood pressure or cholesterol. As such, classic risk factors for atrial fibrillation are unlikely to mediate the association between long working hours and atrial fibrillation. In contrast, there has been the suggestion of a link between extensive overtime working and autonomic nervous system abnormalities,13 a risk factor for atrial fibrillation.14,28,29 As such, stress-related mechanisms that may trigger arrhythmia, such as autonomic dysfunction, might be a more promising focus for future studies on long working hours and atrial fibrillation than mediation via classic cardiovascular disease risk factors.

In absolute terms, the increased risk of atrial fibrillation among individuals with long working hours is relatively modest. The number of cases varied between 13 and 449 in the included studies; none of the study-specific associations between long working hours and atrial fibrillation reached statistical significance at conventional levels. In contrast, the association was highly significant in our pooled sample including a total of 1061 incident atrial fibrillation cases. The method of atrial fibrillation ascertainment was not uniform across studies—in only one study were participants repeatedly assessed using an electrocardiogram, the gold standard method, while in two other studies cases were identified via records from hospital admissions, death certificates or drug reimbursements, and in five studies only records from hospital admissions and deaths were available. The occurrence of atrial fibrillation is likely to be underestimated in the seven record linkage studies as they may miss undiagnosed and mildly symptomatic cases. While the study using an electrocardiogram is stronger methodologically, atrial fibrillation can be episodic and these “paroxysmal” cases are difficult to identify even with an electrocardiogram. Importantly, however, the relative risk of atrial fibrillation among individuals with long working hours was similar across the studies irrespective of the method of ascertainment: 1.4 in the study with ECG ascertainment, 1.3 in studies using hospital, prescription and death records, and 1.4 in those with hospital and death records only. This suggests that misclassification was random in terms of participants’ working hours and has therefore not caused a significant bias.

While novel and large in scale, our study has several limitations. First, as described, heterogeneous assessment of atrial fibrillation is a drawback. Second, working hours and lifestyle factors were only assessed at study induction. As working hours vary over time, our findings may under- or overestimate the true effect due to imprecise measurement of long-term exposure. Similarly, a lack of repeat measurement of lifestyle factors prevented us from examining potential behavioural mediators in the association between long working hours and atrial fibrillation. Third, the overall study population (N = 85 494) included more women (65%) than men (35%). This was because the largest cohort—the Finnish Public Sector study (N = 44 505)—is 81% female reflecting the sex distribution of public sector workers in Finland at the time of study enrolment. That there was no significant sex difference in the association between working hours and atrial fibrillation suggests our sex-adjusted analyses of men and women combined provide an accurate estimation of the association. Fourth, it is noteworthy that despite differences between the studies in terms of year of recruitment (range from 1991 to 2004), study population, location, methodology and settings, there was no significant heterogeneity in study-specific estimates of the association between long working hours and risk of atrial fibrillation. This supports the robustness of the main finding.

Conclusion

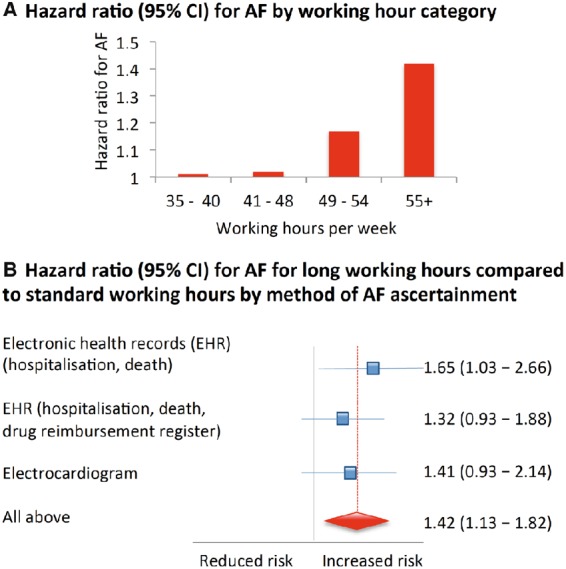

Our findings raise the hypothesis that long working hours may affect the risk of atrial fibrillation (Summarizing Figure). We showed that employees working long hours were 40% more likely to develop this cardiac arrhythmia than those working standard hours. As this association appeared to be independent of known risk factors for atrial fibrillation, further research is needed to determine mechanisms underlying the link between long working hours and atrial fibrillation. Furthermore, the participants of this study were from the UK, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland. Although there is no reason to assume that the association would be dependent on geographical region, the generalizability of our findings to other countries remains to be confirmed.

Summarizing Figure.

Association between working hours and risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) in 85 494 men and women free of AF at baseline. During the mean follow-up of 10.0 years, 1061 developed AF. The figure shows that persons who worked 55 hours or more per week had a 1.4-fold increased risk of AF compared to those working standard 35–40 weekly hours (A). This estimate did not vary according to the method of AF ascertainment (B).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Authors’ contributions

M.K. along with A.T. developed the hypothesis. S.N. and I.M. performed statistical analyses. M.K. wrote the first draft; all authors contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, or, in addition, data acquisition.

Funding

IPD-Work consortium was supported by NordForsk, a Nordic Research Programme on Health and Welfare, the EU New OSH ERA research programme, the Finnish Work Environment Fund, Finland, the Swedish Research Council for Working Life and Social Research, Sweden, Danish National Research Centre for the Working Environment, Denmark. NordForsk and the UK Medical Research Council (K013351 to M.K.).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Falk RH. Atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1067–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schnabel RB, Sullivan LM, Levy D, Pencina MJ, Massaro JM, D'agostino RB Sr, Newton-Cheh C, Yamamoto JF, Magnani JW, Tadros TM, Kannel WB, Wang TJ, Ellinor PT, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ.. Development of a risk score for atrial fibrillation (Framingham Heart Study): a community-based cohort study. Lancet 2009;373:739–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahman F, Kwan GF, Benjamin EJ.. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014;11:639–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huxley RR, Lopez FL, Folsom AR, Agarwal SK, Loehr LR, Soliman EZ, Maclehose R, Konety S, Alonso A.. Absolute and attributable risks of atrial fibrillation in relation to optimal and borderline risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation 2011;123:1501–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lip GY, Tse HF, Lane DA.. Atrial fibrillation. Lancet 2012;379:648–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, Castella M, Diener HC, Heidbuchel H, Hendriks J, Hindricks G, Manolis AS, Oldgren J, Popescu BA, Schotten U, Van Putte B, Vardas P, Agewall S, Camm J, Baron Esquivias G, Budts W, Carerj S, Casselman F, Coca A, De Caterina R, Deftereos S, Dobrev D, Ferro JM, Filippatos G, Fitzsimons D, Gorenek B, Guenoun M, Hohnloser SH, Kolh P, Lip GY, Manolis A, McMurray J, Ponikowski P, Rosenhek R, Ruschitzka F, Savelieva I, Sharma S, Suwalski P, Tamargo JL, Taylor CJ, Van Gelder IC, Voors AA, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Zeppenfeld K.. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESCEndorsed by the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893–2962.27567408 [Google Scholar]

- 7. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Murray KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW; ACC/AHA Task Force Members.. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014;130:2071–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones C, Pollit V, Fitzmaurice D, Cowan C; Guideline Development Group. The management of atrial fibrillation: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2014;348:g3655.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FD, Løchen ML, Löllgen H, Marques-Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, van der Worp HB, van Dis I, Verschuren WM; Authors/Task Force Members.. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–2381.27222591 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kivimaki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Singh-Manoux A, Fransson EI, Alfredsson L, Bjorner JB, Borritz M, Burr H, Casini A, Clays E, De Bacquer D, Dragano N, Erbel R, Geuskens GA, Hamer M, Hooftman WE, Houtman IL, Jöckel KH, Kittel F, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Lunau T, Madsen IE, Nielsen ML, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pejtersen JH, Pentti J, Rugulies R, Salo P, Shipley MJ, Siegrist J, Steptoe A, Suominen SB, Theorell T, Vahtera J, Westerholm PJ, Westerlund H, O'reilly D, Kumari M, Batty GD, Ferrie JE, Virtanen M, IPDW. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a meta-analysis of 603 838 men and women. Lancet 2015;386:1739–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burstein B, Nattel S.. Atrial fibrosis: mechanisms and clinical relevance in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:802–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bhatt AG, Monahan KM.. Fitness and the development of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2015;131:1821–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kageyama T, Nishikido N, Kobayashi T, Kurokawa Y, Kabuto M.. Commuting, overtime, and cardiac autonomic activity in Tokyo. Lancet 1997;350:639.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perkiomaki J, Ukkola O, Kiviniemi A, Tulppo M, Ylitalo A, Kesäniemi YA, Huikuri H.. Heart rate variability findings as a predictor of atrial fibrillation in middle-aged population. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25:719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peter RH, Gracey JG, Beach TB.. Significance of fibrillatory waves and the P terminal force in idiopathic atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 1968;68:1296–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lampert R, Jamner L, Burg M, Dziura J, Brandt C, Liu H, Li F, Donovan T, Soufer R.. Triggering of symptomatic atrial fibrillation by negative emotion. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1533–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kivimaki M, Virtanen M, Kawachi I, Nyberg ST, Alfredsson L, Batty GD, Bjorner JB, Borritz M, Brunner EJ, Burr H, Dragano N, Ferrie JE, Fransson EI, Hamer M, Heikkilä K, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Madsen IE, Nielsen ML, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pejtersen JH, Pentti J, Rugulies R, Salo P, Siegrist J, Steptoe A, Suominen S, Theorell T, Vahtera J, Westerholm PJ, Westerlund H, Singh-Manoux A, Jokela M.. IPD-Work consortium. Long working hours, socioeconomic status and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of published and unpublished data from 222,120 individuals. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;3:27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Virtanen M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Madsen IE, Lallukka T, Ahola K, Alfredsson L, Batty GD, Bjorner JB, Borritz M, Burr H, Casini A, Clays E, De Bacquer D, Dragano N, Erbel R, Ferrie JE, Fransson EI, Hamer M, Heikkilä K, Jöckel KH, Kittel F, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Ladwig KH, Lunau T, Nielsen ML, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pejtersen JH, Pentti J, Rugulies R, Salo P, Schupp J, Siegrist J, Singh-Manoux A, Steptoe A, Suominen SB, Theorell T, Vahtera J, Wagner GG, Westerholm PJ, Westerlund H, Kivimäki M.. Long working hours and alcohol use: systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies and unpublished individual participant data. BMJ 2015;350:g7772.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kivimaki M, Batty GD, Hamer M, Ferrie JE, Vahtera J, Virtanen M, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ.. Using additional information on working hours to predict coronary heart disease a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:457–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sokejima S, Kagamimori S.. Working hours as a risk factor for acute myocardila infarction in Japan: case-control study. BMJ 1998;317:775–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Allan V, Honarbakhsh S, Casas JP, Wallace J, Hunter RT, Schilling R, Perel P, Morley K, Banerjee A, Hemingway H.. Are cardiovascular risk factors also associated with the incidence of atrial fibrillation? A systematic review and field synopsis of 23 factors in 32 population based cohorts of 20 million participants. Thromb Haemost 2017;117:837–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goldberg D, Williams P.. A Users Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Berkshire, Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson Publishing Co; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, Arveiler D, Rajakangas AM, Pajak A.. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project. Registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation 1994;90:583–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Toren K, Schioler L, Soderberg M, Giang KW, Rosengren A.. The association between job strain and atrial fibrillation in Swedish men. Occup Environ Med 2015;72:177–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fransson EI, Stadin M, Nordin M, Malm D, Knutsson A, Alfredsson L, Westerholm PJ.. The association between job strain and atrial fibrillation: results from the Swedish WOLF study. BioMed Res Int 2015;2015:371905.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Larsson SC, Drca N, Wolk A.. Alcohol consumption and risk of atrial fibrillation: a prospective study and dose-response meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miller JD, Aronis KN, Chrispin J, Patil KD, Marine JE, Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS, Calkins H.. Obesity, exercise, obstructive sleep apnea, and modifiable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:2899–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bettoni M, Zimmermann M.. Autonomic tone variations before the onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2002;105:2753–2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen PS, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Nattel S.. Role of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation: pathophysiology and therapy. Circ Res 2014;114:1500–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.