Abstract

Hypoxic-ischemic (HI) brain injury is frequently associated with premature and/or full-term birth-related complications that reflect widespread damage to cerebral cortical structures. Inflammation has been implicated in the long-term evolution and severity of HI brain injury. Inter-Alpha Inhibitor Proteins (IAIPs) are immune modulator proteins that are reduced in systemic neonatal inflammatory states. We have shown that endogenous IAIPs are present in neurons, astrocytes and microglia and that exogenous treatment with human plasma purified IAIPs decreases neuronal injury and improves behavioral outcomes in neonatal rats with HI brain injury. In addition, we have shown that endogenous IAIPs are reduced in the brain of the ovine fetus shortly after ischemic injury. However, the effect of HI on changes in circulating and endogenous brain IAIPs has not been examined in neonatal rats. In the current study, we examined changes in endogenous IAIPs in the systemic circulation and brain of neonatal rats after exposure to HI brain injury. Postnatal day 7 rats were exposed to right carotid artery ligation and 8% oxygen for 2 h. Sera were obtained immediately, 3, 12, 24, and 48 h and brains 3 and 24 h after HI. IAIPs levels were determined by a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in sera and by Western immunoblots in cerebral cortices. Serum IAIPs were decreased 3 h after HI and remained lower than in non-ischemic rats up to 7 days after HI. IAIP expression increased in the ipsilateral cerebral cortices 24 h after HI brain injury and in the hypoxic contralateral cortices. However, 3 h after hypoxia alone the 250 kDa IAIP moiety was reduced in the contralateral cortices. We speculate that changes in endogenous IAIPs levels in blood and brain represent constituents of endogenous anti-inflammatory neuroprotective mechanism(s) after HI in neonatal rats.

Keywords: brain, hypoxia, hypoxic ischemic injury, Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins, sera, neonates

1. Introduction

Hypoxic-Ischemic (HI) brain injury is a result of decreased blood flow to the brain combined with lower-than-normal oxygen concentrations in arterial blood (Dixon et al., 2015; Mehta et al., 2007). HI related events in premature and full-term infants increase mortality and result in long-term neurological deficits including cerebral palsy, epilepsy and seizure disorders, severe learning and mental impairment, cognitive, motor and behavioral developmental problems (Conklin et al., 2008; Fatemi et al., 2009; Kharoshankaya et al., 2016; Pappas et al., 2015). The only currently available strategy to attenuate brain injury in newborns is therapeutic hypothermia (Gluckman et al., 2006; Jacobs et al., 2013; Natarajan et al., 2016; Shankaran, 2012). This therapy is only approved for use in full-term newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) and, unfortunately, is only partially neuroprotective (Gluckman et al., 2006; Jacobs et al., 2013; Natarajan et al., 2016; Shankaran, 2012).

Post-ischemic neuroinflammation is a key pathophysiological factor in the evolution of HI-related brain injury (Ferriero, 2004; Hagberg et al., 2015; Lai et al., 2017; Riljak et al., 2016; Rocha-Ferreira and Hristova, 2016). The first phase of HI injury lasts minutes to hours after the initial insult and is marked by oxidative stress and depletion of energy stores. The second phase of HI injury occurs from hours to days after the insult and is characterized by an intense neuroinflammatory response. This neuroinflammatory response is associated with the release of several pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, recruitment of proteases, activation of resident immune cells (e.g. microglia) and infiltration of circulating immune cells (e.g. circulating monocytes) (Jellema et al., 2013; Liu and McCullough, 2013), which exacerbates brain injury and contributes to later adverse outcomes. Consequently, attenuation of these inflammatory processes could represent a promising strategy to reduce and/or prevent brain damage after HI injury in neonates. However, the inflammatory response that initially is harmful may be beneficial later because inflammation also contributes to many repair processes. Therefore, the timing of initiation of anti-inflammatory therapeutics is critical to the final outcome of brain injury.

Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins (IAIPs) are a family of endogenous serine protease inhibitors found in blood and numerous fetal, neonatal and adult tissues including the brain (Chen et al., 2016; Salier et al., 1996; Spasova et al., 2014; Takano et al., 1999). Two moieties are found in mammalian plasma: Inter-alpha Inhibitor (IαI) composed of two heavy chains (H1 and H2) and a single light chain also called bikunin, and a Pre-alpha Inhibitor (PαI), composed of one heavy (H3) and one light chain. IAIPs have already been shown to have systemic anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting destructive serine proteases, blocking complement activation, and pro-inflammatory cytokine production as well as by promoting the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (Fries and Blom, 2000; Fries and Kaczmarczyk, 2003; Garantziotis et al., 2007; Okroj et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2010). IAIPs have been shown to be reduced in the plasma of premature infants who have systemic inflammatory disorders including sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis (Baek et al., 2003; Chaaban et al., 2010; Chaaban et al., 2009). These findings suggest that inflammatory disorders adversely affect systemic endogenous IAIPs levels in premature neonates. However, there is limited information regarding the effects of HI brain injury on systemic and brain levels of endogenous IAIPs in neonates.

Endogenous IAIPs are expressed in relatively high amounts during development in rodent and ovine brain and are detected in neurons, microglia, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, and in multiple brain regions including cerebral cortex and hippocampus in both neonatal rats and mice (Chen et al., 2016; Spasova et al., 2014). The ubiquitous presence of endogenous IAIPs in numerous types of brain cells and brain regions in the central nervous system (CNS) of rodents suggests that endogenous IAIPs represent an important, but previously unrecognized constituent of the normal brain composition, and most likely function (Chen et al., 2016; Spasova et al., 2014). In addition, we have previously shown that IAIP expression is reduced shortly after ischemia in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum of fetal sheep and returns toward non-ischemic levels between 24 and 48 h after an ischemic insult (Spasova et al., 2016). These findings suggest that ischemia is associated with increased IAIP utilization and/or decreased production in the CNS (Spasova et al., 2016). Nonetheless, brain ischemia in the fetal sheep did not result in alterations in plasma concentrations of IAIPs (Spasova et al., 2016). Therefore, IAIPs represent endogenous anti-inflammatory molecules that could be regulated in the brain during injury related events.

Recent work has also shown that exogenous treatment with IAIPs in neonates exposed to HI reduces neuronal cell death, improves neuronal plasticity, ameliorates complex auditory processing deficits, cognitive function, and behavioral outcomes (Gaudet et al., 2016; Threlkeld et al., 2014; Threlkeld et al., 2017). Administration of urinary bikunin, the light chain of IAIPs demonstrated neuroprotective properties by reducing pro-inflammatory mediators and resulting in milder ischemia related brain injury in young piglets (Wang et al., 2013). The results of the above studies support the contention that IAIPs are endogenously present in brain, levels can be affected by HI injury, and that exogenous treatment with IAIPs potentially have promising neuroprotective properties after neonatal HI. The importance of inflammation in HI related brain damage and the immunomodulatory properties of IAIPs suggest that these proteins could be promising therapeutics to attenuate brain injury after HI in neonates.

Given the above considerations, the objective of the current study was to extend our previous findings to examine potential alterations in endogenous IAIPs in the systemic circulation and brain of neonatal rats after exposure to HI brain injury.

2. Methods

This study was conducted with the approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the use of experimental animals.

2.1 Animal Preparation, Study Groups, and Experimental Design

Subjects were Wistar rats born from time-mated dams obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, Maine, USA). Post-natal (P) day 7 rats were randomly assigned to sham control or HI groups. The Rice-Vannucci method was used to induce the HI injury (Rice et al., 1981). Briefly, each animal was anesthetized with 3–4% isoflurane and anesthesia maintained with 1% isoflurane. Total absence of leg withdrawal reflexes was verified before the onset of surgery. A midline ventral incision was made in the neck. The right common carotid artery (RCCA) was located and ligated. Sham subjects were exposed to the same procedure except the RCCA was not ligated. Body temperature was maintained at 36°C during surgery with an isothermic heating pad (Marks et al., 2010; Mishima et al., 2004; Reinboth et al., 2016; Silveira and Procianoy, 2015). The pups were returned to their dams for 1.5–3 h for feeding and recovery from surgery before exposure to hypoxia (8% oxygen). Subjects exposed to HI were placed in a hypoxia chamber with 8% humidified oxygen and balanced nitrogen for 2 h with a constant temperature of 36°C. Sham subjects were exposed to room air for 2 h. The pups were sham treated (n=8 females/10 males) or remained with their dams until 3 h (n=2 females/3 males), 6 h (n=3 females/3 males), 12 h (n= 5 females/8 males), 24 h (n= 1 female/4 males), 48 h (n= 3 females/2 males), and 7 days (n=1 female/3 males) after HI when they were euthanized. Three hundred to 500 μl of whole blood were collected without the use of anticoagulant from the left ventricle and centrifuged immediately at 5000 rpm at room temperature. The clots were removed and the supernatant collected in a fresh tube and placed on ice for 2 h. Any additional clots that formed also were removed and the supernatant saved at −80°C until analysis. The samples were again centrifuged before analysis and the supernatant were used for ELISA.

Brain tissue was obtained from the sham, and HI animals at 3 h and 24 h (n=8 for right cortices and n=6–8 for left cortices in each group) after exposure to HI. Brains were dissected to isolate the right HI or left non-ischemic hypoxic cerebral cortices in the sham and HI groups. The right cerebral cortex represented the hypoxic-ischemic damaged brain tissue. The left cerebral cortex represented the tissue exposed to hypoxia, but not ischemia. Brain tissues for this study were residual samples from earlier projects, and consequently, right and left cortices were not available from the same animals and, consequently, could not be compared.

2.2 Competitive ELISA to measure IAIPs concentrations in rat sera

Serum concentrations of IAIPs in sham and HI rats were measured by a competitive ELISA using a polyclonal antibody raised against rat IAIPs (R-21 pAb). The R-21 pAb was generated by immunization of rabbits with rat serum derived IAIPs that cross-react with mouse and human IAIPs and detect both the 250 kDa IaI and 125 kDa PaI proteins by Western immunoblot analysis. The R-21 pAb was purified by affinity chromatography using rProtein-A column (Tosoh Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan) and purified IgG was conjugated with biotin using an EZ-Link NHS-LC-Biotin kit (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Rat IAIPs that were used to establish the standard curve for quantitative analysis were extracted and purified as previously described for human IAIPs (Spasova et al., 2014; Spasova et al., 2016). Briefly, IAIPs were extracted from rat serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) using a monolithic anion-exchange chromatographic method. After binding, the column was washed with 200 nM NaCl/200nM acetate buffer (pH 3.0). IAIPs were eluted from the column using a buffer containing 750 mM NaCl, and concentrated and buffer exchanged using a tangential flow filtration system (Labscale, Millipore, Chicago, IL, USA). Purified IAIPs diluted in 100 mM NaPO4 buffer at pH 6.5 and 50 ng per well were coated on ninety-six-well high-binding microplates (Microlon 600, Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC, USA) for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. After blocking with 200 μL of 5% non-fat dried milk in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.05% Tween, 50 μL of sample and the serially diluted IAIPs standards were added to the wells. Then, 50 μL of biotin-conjugated R-21 pAb (1:500 dilution in PBS) was also added to each well. Plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed with PBS plus 0.05% Tween using an automated plate washer (Biotek EL-404, Winooski, VT, USA). Pierce streptavidin-poly-horseradish-peroxidase (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) was added to each well to detect the bound biotinylated R-21 pAb and the plate was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, 100 μL Enhanced K-Blue TMB substrate (Neogen Corp, Lexington, KY, USA) was added to the wells and the reaction was stopped with 100 μL 1 N HCl solution. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured on SpectraMAX Plus microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Concentrations in the samples were calculated by comparison of the absorbance signal to the established standard curve. Each sample was measured in triplicate and assays were repeated at least twice on all samples.

2.3 Preparation of cytosolic brain fractions

We examined the cytosolic fraction for this study because the primary antibody R-21 recognized IAIPs only in the cytosol (Spasova et al., 2014). Cytosolic brain fractions for quantification of IAIPs in the cerebral cortical samples were extracted in buffer A (TRIS 10 mM, 0.32 M Sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, pH 6.8) containing 1% of complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) (Spasova et al., 2014; Spasova et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). The extract was then centrifuged three times as follows: at 850 g for 10 minutes, 40,000 g and for 1 h and 100,000 g for 1 h at a temperature of 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and transferred in a new tube after each centrifugation. Total protein concentrations of the extracts were determined using bicinchoninic acid protein assay (BCA, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Aliquots of the extracted samples were stored at −80°C until analysis.

2.4 Western immunoblot detection

A total of 10 μg protein per well were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and polyvinyl difluoride membrane (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes (0.2 μm, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) using a semi-dry technique. Membranes were incubated with the rabbit polyclonal antibody against IAIPs (pR-21 Ab, 1:5000 dilution, ProThera Biologics, East Providence, RI, USA) and β actin antibody (1:10000 dilution) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then incubated with peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse (1:10000 dilution, Alpha Diagnostic, San Antonio, TX, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Before exposure to autoradiography film (Daigger, Vernon Hills, IL, USA), the bound secondary antibody chemiluminescence was visualized by adding Western Blotting Detection reagents (ECL plus, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Experimental samples were normalized to a reference protein standard that was obtained from a homogenate protein pool derived from the cerebral cortex of a single dam for right cerebral cortices and of another single dam for the left cortices. We have previously used and described this method of normalization in studies on sheep (Chen et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2015; Spasova et al., 2016). These internal control (IC) protein standard samples served as quality control for loading, transfer of the samples, normalization of the densitometry values, and allowed for accurate comparisons among the different immunoblots. β actin expression was also used as a loading control to ensure that equal amounts of protein were applied to each lane. Each immunoblot included samples from the sham and 3 h or sham and 24 h study groups and IC samples placed in three lanes, as the first, middle, and last samples on each immunoblot. Molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) were included in each immunoblot. The R-21 pAb detects IAIP bands at 125 and 250 kDa (PαI and IαI) in brain samples. Uniformity of transfer to the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes was confirmed by Ponceau S staining (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.5 Densitometric analysis

Band intensities were analyzed with a Gel-Pro Analyzer (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). All experimental samples were normalized to the respective average of the three IC samples on each immunoblot. The final values represented averages of the densitometry values obtained from at least three different immunoblots and were presented as a ratio to the IC sample.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism®. After homogeneity of variance confirmation by Bartlett test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the differences among the groups. When a significant difference was detected by ANOVA, the Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to further describe the statistically significant differences between the sham group and the other groups. Values are mean ± SD. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

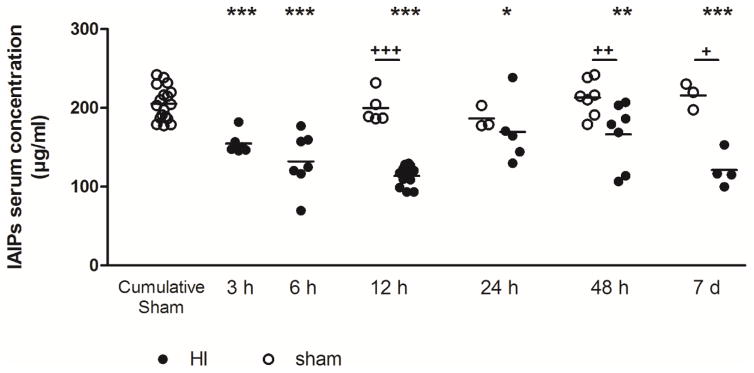

3.1 IAIPs concentrations in sera

IAIPs concentrations measured in the sera from sham treated neonatal rats from P7 up to P14 did not vary as a function of sampling time after birth (mean 154.9, range 177.6–242.0 μg/ml). Therefore, the serum values from the sham control rats were combined into a single sham group (Fig. 1, open circles). In contrast, the serum IAIP concentrations decreased rapidly after HI; the mean concentration 3 h after HI was 154.9 ± 13.9 versus 205.5 ± 21.1 μg/ml in the cumulative sham group. The IAIP concentrations remained consistently below the cumulative sham control values (P<0.05) up to 7 days after HI (Fig. 1) except 24 h after HI. Significant differences were also observed at 12 h, 4 h and 7 d after HI when the experimental (closed circles) were compared with the individual sham group (open circles). Sex differences in serum IAIP levels were not detected between males and females within the sham or HI groups of neonatal rats (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Serum concentrations of IAIPs after HI brain injury in neonatal rats. Venous blood samples were collected from the left ventricle, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h or 7 d after 2 h hypoxia. IAIPs were quantified by ELISA. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of n = 4 to 18 animals. Statistical comparisons were performed by one-way ANOVA follow by a Bonferroni post hoc test compared with the sham cumulative group, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P< 0.001 and compared to the HI animals at 12 h, 24 h, 48 h and 7 d time points with the matched sham group, +P < 0.05; ++P < 0.01; +++P< 0.001.

3.2 IAIPs expression in brain

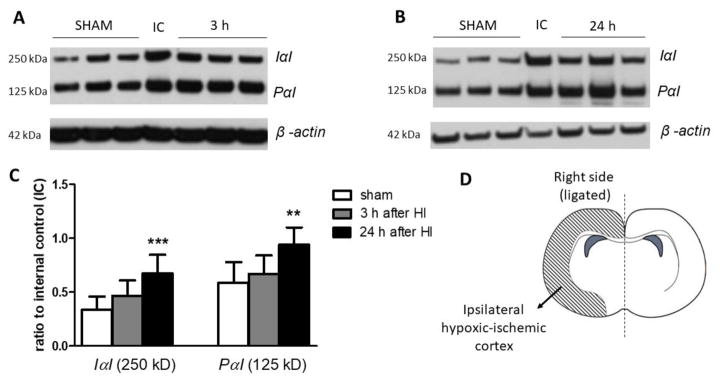

Cytosolic brain extracts from the right HI and left hypoxic cerebral cortices were obtained for IαI and PαI quantification by Western immunoblot. Both the major moieties of IAIPs, IαI and PαI, were detected by Western immunoblot (Figures 2 and 3) (Spasova et al., 2014; Spasova et al., 2016). IαI was higher (P<0.001) in ipsilateral damaged cerebral cortices 24 h after HI compared with the right cerebral cortex in the sham control group (Figure 2C). Likewise, the expression of PαI showed a similar pattern of change 24 h after HI (P<0.01, Figure 2C). Although the values of the IαI and PαI proteins also appeared higher 3 h after HI, the differences between HI and the sham group did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 2.

The 250 kDa IαI and 125 kDa PαI expression in neonatal rat right hypoxic-ischemic cerebral cortices after HI.

A. Representative Western immunoblot for IαI and PαI in the sham and 3 h after HI group

B. Representative Western immunoblot for IαI and PαI in the sham and 24 h after HI group.

C. Graph shows analysis of IαI and PαI expression. Data plotted as the ratio to the internal control standard protein derived from one adult female rat brain.

D. Brain diagram shows the side used for the Western immunoblots.

Each data point represents the mean ± SD of n=8 animals per group. Statistical comparison was performed by one-way ANOVA follow by a Bonferroni post hoc test compared with the sham group, **P < 0.01; ***P< 0.001.

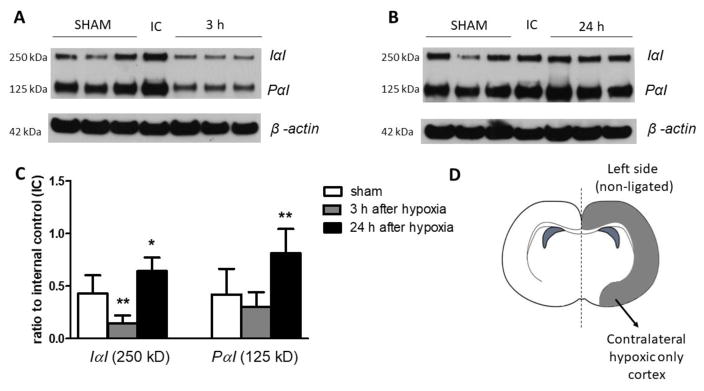

Fig. 3.

The 250 kDa IαI and 125 kDa PαI expression in neonatal rat cerebral left hypoxic cortices after HI.

A. Representative Western immunoblot for IαI and PαI in the sham and 3 h after HI group

B. Representative Western immunoblot for IαI and PαI in the sham and 24 h after HI group.

C. Graph shows analysis of IαI and PαI expression. Data plotted as the ratio to the internal control standard protein derived from one adult female rat brain.

D. Brain diagram shows the side used for the Western immunoblots.

Each data point represents the mean ± SD of n=8 animals in sham group, n=7 in 3 h after HI group and n=6 in the 24 h after HI group. Statistical comparison was performed by one-way ANOVA follow by a Bonferroni post hoc test compared with the sham group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

In the contralateral hypoxic cerebral cortices, the expression of the IαI protein moiety exhibited a significant (P<0.01) decrease 3 h after HI (Figure 3A and C). Twenty-four h after HI, the expression of both IαI and PαI protein moieties in the hypoxic cerebral cortices showed significant increases over the values in the sham group. The samples for left and right cerebral cortices were not derived from the same animals so that the results were not compared and were always normalized to the corresponding internal control.

Discussion

The overall purpose of the current study was to examine changes in endogenous levels of IAIPs in the systemic circulation and CNS as a function of the time interval after HI in neonatal rats. The novel findings of the current study are as follows: First, that there was early and sustained decrease in the circulating concentrations of the IAIPs in blood of neonatal rats after HI; and second, there were time and insult dependent alterations in the expression of endogenous IAIPs in the cerebral cortices after HI.

In current study, we found a decrease in the circulating levels of IAIPs from 3 h up to 7 days after HI in neonatal rats. The decreases in the serum IAIP concentrations after HI in the neonatal rat suggest increased utilization, degradation, and/or decreased production of circulating IAIPs after neonatal HI. IAIPs are synthesized in the liver, produced in somatic organs, and then released into the systemic circulation (Spasova et al., 2014). Our findings showing a decrease in circulating IAIPs are consistent with the decreases in endogenous IAIPs in the blood of premature infants after exposure to other systemic inflammatory disorders (Baek et al., 2003; Chaaban et al., 2010; Chaaban et al., 2009). Likewise, the findings are consistent with decreases in endogenous blood levels of IAIPs in adults after stroke (Kashyap et al., 2009). In contrast, our previous findings showed that plasma IAIP concentrations were not altered in ovine fetuses up to 48 h after brain ischemia (Spasova et al., 2016). Discrepancies between the current study and our previous work could be attributed to differences between the sheep and rodent models, disparities between the fetal sheep and postnatal rodent brain development (Clancy et al., 2007; Dobbing and Sands, 1979; Romijn et al., 1991; Semple et al., 2013) and differences in the duration of blood sampling after the insults. The patterns of change in the circulating levels of IAIPs observed after cerebral ischemia in the ovine fetus and HI in neonatal rodents would not necessarily be expected to be comparable because our work in sheep examined brain ischemia alone, whereas HI in the rat model includes carotid ligation combined with systemic exposure to hypoxia. In this regard, the decreases in circulating IAIP levels in the HI rat model could be the result of HI related brain injury/inflammation and/or the effects of reduced systemic oxygen exposure for 2 h. In addition, the duration of examination after HI was much longer in the neonatal rats compared to the fetal sheep, particularly considering differences in the lifespan between the two species.

The decreases in serum IAIP concentrations suggest that these molecules could be utilized, consumed, and/or exhibit reduced production in association with HI-related brain inflammation and/or systemic hypoxia. The protective effects of ulinastatin (bikunin) against ischemic-reperfusion injury to the liver, kidney, intestine, lung and brain would tend to further support this concept (Cho et al., 2015; Guan et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017; Qian et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2014). The HI related alterations in IAIPs in blood could represent part of an endogenous protective mechanism because perinatal systemic inflammation has been associated with increased incidences of brain damage (Ranchhod et al., 2015). IAIPs are large hydrophilic molecules that are not likely to leak across the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) to reach the brain parenchyma under normal conditions. Nonetheless, circulating IAIPs could be transported across the BBB by specific transporters (Abbott et al., 2006). Whether the IAIPs could penetrate an intact or HI injured BBB would be an important focus for future investigation. Even though IAIPs are not likely to penetrate the BBB because of their size, circulating IAIPs could still attenuate HI related systemic inflammation, and/or exert their beneficial effects on the brain by reducing the relay of pro-inflammatory signals across the cerebral vascular endothelium.

The decrease in IAIP expression in the contralateral hypoxic alone cortex during the first hours after HI suggests utilization of the endogenous proteins in response to hypoxia. In contrast to the hypoxic cortex and to our previous findings in the fetal sheep brain 4 h after ischemia (Spasova et al., 2016), a decrease was not observed in the ipsilateral HI injured cerebral cortex at 3 or 24 h after HI. The early decrease in the IαI protein moiety in the hypoxic cortex after HI could suggest that early modulation in IAIP expression is related to systemic events in circulating mediators. On the other hand, the increases in cerebral cortical levels of IAIPs 24 h after HI on both sides of the brain are most likely a result of increased local synthesis because IAIPs are large proteins that most likely do not cross the BBB and systemic levels of IAIPs decreased after HI. These increases in IAIPs in both the ipsilateral HI and contralateral hypoxic sides at 24 h after HI suggest that the mechanisms may involve systemic as well as local factors. In addition, these findings also suggest that systemic oxygen deprivation due to hypoxia alone could contribute to the changes in endogenous levels of brain IAIPs.

The increase in endogenous IAIPs 24 h after HI in the neonatal rats differs from our findings after brain ischemia in fetal sheep (Spasova et al., 2016), in which we observed a rapid reduction in IAIP expression in the brain with a return toward control levels at 24 and 48 h after ischemia. Differences between the findings in the present study after HI and our previous work in fetal sheep after ischemia could be related to species differences, prenatal versus postnatal brain development (Clancy et al., 2007; Dobbing and Sands, 1979; Romijn et al., 1991; Semple et al., 2013), the timing of the insults in relationship to the brain acquisition, and/or differences in the insults, e.g. pure ischemia versus HI. The differences in the pattern of IAIP expression observed in hypoxic only and HI cortices further support the contention that there is an insult-dependent regulation of IAIPs. In addition, it is important to emphasize that in our previous study in fetal sheep, we did not have values beyond 48 h after ischemia. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that IAIP levels in the brain might have increased at a later time point because we observed a normalization of the values by 24 and 48 h after ischemia (Spasova et al., 2016).

Neuroinflammation is increasingly recognized as an important factor in the normal development of the brain (Bilbo and Schwarz, 2009, 2012; Schafer and Stevens, 2015) and is a major contributor to the evolution of HI related brain injury (Ferriero, 2004; Lai et al., 2017; Riljak et al., 2016). On another hand, the immune system also participates in CNS repair processes (Vidale et al., 2017; Wattananit et al., 2016). Pro-inflammatory cytokines have been shown to cross the BBB (Sadowska et al., 2016) and are important mediators in pathways associated with perinatal brain injury caused by a variety of insults. Overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α or IL-6 have been identified in the neonatal brain after HI and can predispose to a poor prognosis as well (Sadowska et al., 2012; Shang et al., 2014). IAIPs are a family of structurally related serine protease inhibitors with immune modulating capacities that have been shown to down-regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines and upregulate anti-inflammatory cytokines resulting in decreased inflammation in systemic disorders (Lim, 2013; Opal et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2010). Therefore, IAIPs could represent endogenous neuroprotective proteins that influence neuroinflammatory processes in the brain.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, it is important to emphasize that there are differences in outcomes between male and female subjects in response to HI brain injury (Demarest et al., 2016; Diaz et al., 2017; Dipietro and Voegtline, 2017). The limited number of samples available from our previous work did not allow for analysis of potential sex-related differences in endogenous IAIP expression in the brain. However, future investigations would be of interest to determine if there are sex-related differences in endogenous IAIP expression. In addition, we did not determine differences by Western immunoblot with reference to specific brain regions (Chen et al., 2016).

In summary, exposure to HI in neonatal rats is associated with early and sustained reductions in serum levels of IAIPs and later increases in cerebral cortical IAIPs. We speculate that after an early reduction endogenous IAIPs in response to hypoxia, the increases in endogenous IAIPs within the brain 24 h after HI may reflect the onset of a repair processes. In addition, the decreased levels of circulating IAIPs may result from systemic hypoxia and/or HI related neuroinflammation. In future studies, it will be of importance to examine correlations between IAIPs and levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain and circulation of neonatal rodents after HI. Moreover, it would also be of interest to examine the effects of longer periods of recovery from HI on IAIPs in blood and brain.

Highlights.

Neuroinflammation is a key mechanism implicated in hypoxic-ischemic brain injury

IAIPs may represent an endogenous anti-inflammatory neuroprotective factor

Serum IAIPs are decreased after neonatal hypoxic ischemic brain injury

Hypoxic ischemic injury results in increased IAIPs expression in neonatal brain

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this publication was supported by the American Heart Association and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under the following award numbers: American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award: 13POST16860015 to J.Z., Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30GM114750, National Institutes of Health 1R21NS095130, and 1R21NS096525. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek YW, Brokat S, Padbury JF, Pinar H, Hixson DC, Lim YP. Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins in infants and decreased levels in neonatal sepsis. Journal of Pediatrics. 2003;143:11–15. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(03)00190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. Early-life programming of later-life brain and behavior: a critical role for the immune system. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009:3. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.014.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2012;33:267–286. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaaban H, Shin M, Sirya E, Lim YP, Caplan M, Padbury JF. Inter-Alpha Inhibitor Protein Level in Neonates Predicts Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;157:757–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaaban H, Singh K, Huang J, Siryaporn E, Lim YP, Padbury JF. The Role of Inter-Alpha Inhibitor Proteins in the Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis. Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;154:620–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rivard L, Naqvi S, Nakada S, Padbury JF, Sanchez-Esteban J, Stopa EG, Lim YP, Stonestreet BS. Expression and localization of Inter-alpha inhibitors in the rodent brain. Neuroscience. 2016;324:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Threlkeld SW, Cummings EE, Juan I, Makeyev O, Besio WG, Gaitanis J, Banks WA, Sadowska GB, Stonestreet BS. Ischemia-reperfusion impairs blood-brain barrier fucntion and alters tight junction protein expression in the ovine fetus. Neuroscience. 2012;226:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XD, Sadowska GB, Zhang JY, Kim JE, Cummings EE, Bodge CA, Lim YP, Makeyev O, Besio WG, Gaitanis J, Threlkeld SW, Banks WA, Stonestreet BS. Neutralizing anti-interleuldn-1 beta antibodies modulate fetal blood-brain barrier function after ischemia. Neurobiology of Disease. 2015;73:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Shin MS, Ko IG, Kim SE, Kim CJ, Sung YH, Yoon HS, Lee BJ. Ulinastatin inhibits cerebral ischemia-induced apoptosis in the hippocampus of gerbils. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2015;12:1796–1802. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, Finlay BL, Darlington RB, Arland KJS. Extrapolating brain development from experimental species to humans. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:931–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin HM, Salorio CF, Slomine BS. Working memory performance following paediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2008;22:847–857. doi: 10.1080/02699050802403565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarest TG, Schuh RA, Waddell J, McKenna MC, Fiskum G. Sex-dependent mitochondrial respiratory impairment and oxidative stress in a rat model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2016;137:714–729. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz J, Abiola S, Kim N, Avaritt O, Flock D, Yu J, Northington FJ, Chavez-Valdez R. Therapeutic Hypothermia Provides Variable Protection against Behavioral Deficits after Neonatal Hypoxia-Ischemia: A Potential Role for Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Developmental Neuroscience. 2017;39:257–272. doi: 10.1159/000454949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipietro JA, Voegtline KM. The gestational foundation of sex differences in development and vulnerability. Neuroscience. 2017;342:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon BJ, Reis C, Ho WM, Tang JP, Zhang JH. Neuroprotective Strategies after Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16:22368–22401. doi: 10.3390/ijms160922368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J, Sands J. COMPARATIVE ASPECTS OF THE BRAIN GROWTH SPURT. Early Human Development. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi A, Wilson MA, Johnston MV. Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy in the Term Infant. Clinics in Perinatology. 2009;36:835-+. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1985–1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries E, Blom AM. Bikunin - not just a plasma proteinase inhibitor. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2000;32:125–137. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries E, Kaczmarczyk A. Inter-alpha-inhibitor, hyaluronan and inflammation. Acta Biochimica Polonica. 2003;50:735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garantziotis S, Hollingsworth JW, Ghanayem RB, Timberlake S, Zhuo LS, Kimata K, Schwartzt DA. Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor attenuates complement activation and complement-induced lung injury. Journal of Immunology. 2007;179:4187–4192. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet CM, Lim YP, Stonestreet BS, Threlkeld SW. Effects of age, experience and inter-alpha inhibitor proteins on working memory and neuronal plasticity after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Behavioural Brain Research. 2016;302:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman PD, Gunn AJ, Wyatt JS. Hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:1644–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan LY, Liu HY, Fu PY, Li ZN, Li PD, Xie LJ, Xin MG, Wang ZP, Li W. The Protective Effects of Trypsin Inhibitor on Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury and Liver Graft Survival. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/1429835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg H, Mallard C, Ferriero DM, Vannucci SJ, Levison SW, Vexler ZS, Gressens P. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2015;11:192–208. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003311.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellema RK, Passos VL, Zwanenburg A, Ophelders D, De Munter S, Vanderlocht J, Germeraad WTV, Kuypers E, Collins JJP, Cleutjens JPM, Jennekens W, Gavilanes AWD, Seehase M, Vles HJ, Steinbusch H, Andriessen P, Wolfs T, Kramer BW. Cerebral inflammation and mobilization of the peripheral immune system following global hypoxia-ischemia in preterm sheep. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2013:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap RS, Nayak AR, Deshpande PS, Kabra D, Purohit HJ, Taori GM, Daginawala HF. Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain 4 is a novel marker of acute ischemic stroke. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2009;402:160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharoshankaya L, Stevenson NJ, Livingstone V, Murray DM, Murphy BP, Ahearne CE, Boylan GB. Seizure burden and neurodevelopmental outcome in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2016;58:1242–1248. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai JCY, Rocha-Ferreira E, Ek CJ, Wang XY, Hagberg H, Mallard C. Immune responses in perinatal brain injury. Brain Behavior and Immunity. 2017;63:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YP. ProThera Biologics, Inc.: a novel immunomodulator and biomarker for life-threatening diseases. Rhode Island medical journal. 2013;96:16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu FD, McCullough LD. Inflammatory responses in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2013;34:1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Shen JE, Zou F, Zhao YF, Li B, Fan MX. Effect of ulinastatin on the permeability of the blood-brain barrier on rats with global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury as assessed by MRI. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2017;85:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks K, Shany E, Shelef I, Golan A, Zmora E. Hypothermia: A Neuroprotective Therapy for Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy. Israel Medical Association Journal. 2010;12:494–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SL, Manhas N, Rahubir R. Molecular targets in cerebral ischemia for developing novel therapeutics. Brain Research Reviews. 2007;54:34–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima K, Ikeda T, Yoshikawa T, Aoo N, Egashira N, Xia YX, Ikenoue T, Iwasaki K, Fujiwara M. Effects of hypothermia and hyperthermia on attentional and spatial learning deficits following neonatal hypoxia-ischemic insult in rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2004;151:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan G, Pappas A, Shankaran S. Outcomes in childhood following therapeutic hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) Seminars in Perinatology. 2016;40:549–555. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okroj M, Holmquist E, Sjolander J, Corrales L, Saxne T, Wisniewski HG, Blom AM. Heavy Chains of Inter Alpha Inhibitor (I alpha I) Inhibit the Human Complement System at Early Stages of the Cascade. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:20100–20110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.324913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opal SM, Lim YP, Cristofaro P, Artenstein AW, Kessimian N, Delsesto D, Parejo N, Palardy JE, Siryaporn E. Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins: a novel therapeutic strategy for experimental anthrax infection. Shock. 2011;35:42–44. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e83204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas A, Shankaran S, McDonald SA, Vohr BR, Hintz SR, Ehrenkranz RA, Tyson JE, Yolton K, Das A, Bara R, Hammond J, Higgins RD Hypothermia Extended Follow-Up S. Cognitive Outcomes After Neonatal Encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2015;135:E624–E634. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian ZY, Yang MF, Zuo KQ, Xiao HB, Ding WX, Cheng J. Protective effects of ulinastatin on intestinal injury during the perioperative period of acute superior mesenteric artery ischemia. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2014;18:3726–3732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranchhod SM, Gunn KC, Fowke TM, Davidson JO, Lear CA, Bai J, Bennet L, Mallard C, Gunn AJ, Dean JM. Potential neuroprotective strategies for perinatal infection and inflammation. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2015;45:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinboth BS, Koster C, Abberger H, Prager S, Bendix I, Felderhoff-Muser U, Herz J. Endogenous hypothermic response to hypoxia reduces brain injury: Implications for modeling hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and therapeutic hypothermia in neonatal mice. Experimental Neurology. 2016;283:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JE, Vannucci RC, Brierley JB. The influence of immaturity on hypoxic-ischemic brain-damage in the rat. Annals of Neurology. 1981;9:131–141. doi: 10.1002/ana.410090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riljak V, Kraf J, Daryanani A, Jiruska P, Otahal J. Pathophysiology of Perinatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy - Biomarkers, Animal Models and Treatment Perspectives. Physiological Research. 2016;65:S533–S545. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Ferreira E, Hristova M. Plasticity in the Neonatal Brain following Hypoxic-Ischaemic Injury. Neural Plasticity. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4901014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romijn HJ, Hofman MA, Gramsbergen A. At what age is the developing cerebral cortex of the rat comparable to that of the full-term newborn human baby? Early Human Development. 1991;26:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(91)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowska GB, Chen XD, Zhang JY, Lim YP, Cummings EE, Makeyev O, Besio WG, Gaitanis J, Padbury JF, Banks WA, Stonestreet BS. Interleukin-1 beta transfer across the blood-brain barrier in the ovine fetus (vol 35, pg 1388, 2015) Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2016;36:1477–1477. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowska GB, Threlkeld SW, Flangini A, Sharma S, Stonestreet BS. Ontogeny and the effects of in utero brain ischemia on interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6 protein expression in ovine cerebral cortex and white matter. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2012;30:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salier JP, Rouet P, Raguenez G, Daveau M. The inter-alpha-inhibitor family: From structure to regulation. Biochemical Journal. 1996;315:1–9. doi: 10.1042/bj3150001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Stevens B. Microglia Function in Central Nervous System Development and Plasticity. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2015:7. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple BD, Blomgren K, Gimlin K, Ferriero DM, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Brain development in rodents and humans: Identifying benchmarks of maturation and vulnerability to injury across species. Progress in Neurobiology. 2013;106:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Mu L, Guo XX, Li YH, Wang LM, Yang WH, Li SJ, Shen Q. Clinical significance of interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2014;8:1259–1262. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran S. Childhood Outcomes after Hypothermia for Neonatal Encephalopathy (vol 366, pg 2085, 2012) New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:1073–1073. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira RC, Procianoy RS. Hypothermia therapy for newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Jornal De Pediatria. 2015;91:S78–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K, Zhang LX, Bendelja K, Heath R, Murphy S, Sharma S, Padbury JF, Lim YP. Inter-Alpha Inhibitor Protein Administration Improves Survival From Neonatal Sepsis in Mice. Pediatric Research. 2010;68:242–247. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181e9fdf0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasova MS, Chen X, Sadowska GB, Horton ER, Lim YP, Stonestreet BS. Ischemia reduces inter-alpha inhibitor proteins in the brain of the ovine fetus. Developmental neurobiology. 2016 doi: 10.1002/dneu.22451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasova MS, Sadowska GB, Threlkeld SW, Lim YP, Stonestreet BS. Ontogeny of inter-alpha inhibitor proteins in ovine brain and somatic tissues. Exp Biol Med. 2014;239:724–736. doi: 10.1177/1535370213519195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M, Mori Y, Shiraki H, Horie M, Okamoto H, Narahara M, Miyake M, Shikimi T. Detection of bikunin mRNA in limited portions of rat brain. Life Sciences. 1999;65:757–762. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlkeld SW, Gaudet CM, La Rue ME, Dugas E, Hill CA, Lim YP, Stonestreet BS. Effects of inter-alpha inhibitor proteins on neonatal brain injury: Age, task and treatment dependent neurobehavioral outcomes. Experimental Neurology. 2014;261:424–433. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlkeld SW, Lim YP, La Rue M, Gaudet C, Stonestreet BS. Immuno-modulator inter-alpha inhibitor proteins ameliorate complex auditory processing deficits in rats with neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidale S, Consoli A, Arnaboldi M, Consoli D. Postischemic Inflammation in Acute Stroke. Journal of Clinical Neurology. 2017;13:1–9. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2017.13.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XC, Xue QH, Yan FX, Li LH, Liu JP, Li SJ, Hu SS. Ulinastatin as a neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory agent in infant piglets model undergoing surgery on hypothermic low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2013;23:209–216. doi: 10.1111/pan.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XC, Xue QH, Yan FX, Liu JP, Li SJ, Hu SS. Ulinastatin Protects against Acute Kidney Injury in Infant Piglets Model Undergoing Surgery on Hypothermic Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Plos One. 2015:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattananit S, Tornero D, Graubardt N, Memanishvili T, Monni E, Tatarishvili J, Miskinyte G, Ge RM, Ahlenius H, Lindvall O, Schwartz M, Kokaia Z. Monocyte-Derived Macrophages Contribute to Spontaneous Long-Term Functional Recovery after Stroke in Mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36:4182–4195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4317-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Luo Q, Fang H. Mechanism of ulinastatin protection against lung injury caused by lower limb ischemia-reperfusion. Panminerva Medica. 2014;56:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]