Abstract

To identify the prevalence and characteristics of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection (CA-CDI) in southwest China, we conducted a cross-sectional study. 978 diarrhea patients were enrolled and stool specimens’ DNA was screened for virulence genes. Bacterial culture was performed and isolates were characterized by PCR ribotyping and multilocus sequence typing. Toxin genes tcdA and/or tcdB were found in 138/978 (14.11%) cases for fecal samples. A total of 55 C. difficile strains were isolated (5.62%). The positive rate of toxin genes and isolation results had no statistical significance between children and adults groups. However, some clinical features, such as fecal property, diarrhea times before hospital treatment shown difference between two groups. The watery stool was more likely found in children, while the blood stool for adults; most of children cases diarrhea ≤3 times before hospital treatment, and adults diarrhea >3 times. Independent risk factor associated with CA-CDI was patients with fever. ST35/RT046 (18.18%), ST54/RT012 (14.55%), ST3/RT001 (14.55%) and ST3/RT009 (12.73%) were the most distributed genotype profiles. ST35/RT046, ST3/RT001 and ST3/RT009 were the commonly found in children patients but ST54/RT012 for adults. The prevalence of CA-CDI in Yunnan province was relatively high, and isolates displayed heterogeneity between children and adults groups.

Introduction

Clostridium difficile is an important cause of antibiotic associated diarrhea in patients after hospitalization and antibiotic treatment1. C. difficile infection (CDI) caused by the toxigenic strains lead to patients with symptoms ranging from asymptomatic colonization to mild diarrhea and life threatening pseudomembranous colitis or rare intestinal obstruction1,2. Over the past several years, CDI has surpassed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as the most common hospital-acquired infection3. Although elderly hospitalized patients receiving antibiotics are still the main group with high risk of infection, it is increasingly being recognized that some CDI cases are acquired outside health care facilities, such as younger individuals within community4,5. Data from the United States, Canada, and Europe suggest that approximately 20–27% of all CDI cases are community associated (CA-CDI), with an incidence of 20–30 per 100,000 populations6,7.

The major pathogenic mechanism of C. difficile is the production of enterotoxin A and cytotoxin B, encoded by tcdA and tcdB genes, which are located, along with surrounding regulatory genes (Paloc)4,8. In addition to toxins A and B, parts of C. difficile can produce binary toxin, encoded by cdtA and cdtB genes, and also closely related to the pathogenesis of CDI8. Over the past decade, the hypervirulent C. difficile isolate, known as restriction endonuclease type BI/pulsed-field type NAP1, toxinotype III, or PCR ribotype (RT) 027, caused several outbreaks and infections with increased incidence and severity in hospitals in 40 states in USA, in all the provinces in Canada and in most European countries since firstly emerged in North American in 20059,10. Other emergent strains of C. difficile RT078 also causes severe disease especially associated with CA-CDI11.

Although the high rate (~70%) of C. difficile colonization in infants <1 year of age12, the epidemiology of C. difficile in the pediatric population remains poorly understood. Information on CDI in China, especially with a national perspective, is limited. In recent years, many studies, which have been done within single hospital or several hospitals in one place, increased dramatically13,14. However, data on CA-CDI in China are extremely rare. According to the definition of CA-CDI, we first investigated the demography, prevalence and molecular characteristics of C. difficile among 978 diarrhea cases of outpatients in Yunnan province, southwest China.

Results

Clinical features

Among the 978 community-acquired diarrhea patients, 712 cases (72.80%) were children, 266 (27.2%) were adults. The average age was 1.35 ± 2.24 years for children and 48.39 ± 17.72 for adults. The clinical characteristics of two patient groups were different, as shown in Table 1. Except for use antibiotics before hospitals treatment, duration of vomiting and vomit frequency, all the clinical features of two groups were statistical significance (P < 0.05). In children group, the proportion of male, fevers and vomit, the watery stool of fecal property and diarrhea days ≤3 before hospitals treatments were higher than adults; while, the diarrhea days >3 before hospitals treatments and the mucoid, blood stool were more commonly found in adults diarrhea cases. Children patients were enrolled from all the four sentinel hospitals and adults’ cases were collected only from hospital A and D.

Table 1.

The comparison of clinical features between children and adults in this study.

| Parameter | Factors | Age groups | χ2 | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children (cases) | % | Adults (cases) | % | ||||

| Sex | Male | 447 | 62.78 | 137 | 51.5 | 10.237 | 0.001 |

| Female | 265 | 37.22 | 129 | 48.5 | |||

| Sentinel hospitals | A | 143 | 20.08 | 85 | 31.95 | 448.622 | <0.001 |

| B | 411 | 57.73 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| C | 86 | 12.08 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| D | 72 | 10.11 | 181 | 68.05 | |||

| Departments | Internal Medicine | 295 | 41.43 | 266 | 100 | 271.590 | <0.001 |

| Pediatric Clinic | 417 | 58.57 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Years | 2013 | 144 | 20.22 | 32 | 12.03 | 94.470 | <0.001 |

| 2014 | 335 | 47.05 | 214 | 80.45 | |||

| 2015 | 200 | 28.09 | 20 | 7.52 | |||

| 2016 | 33 | 4.64 | 0 | 0.00 | |||

| Fever | Yes | 295 | 41.43 | 24 | 9.02 | 92.551 | <0.001 |

| No | 417 | 58.57 | 242 | 90.98 | |||

| Vomit | Yes | 293 | 41.15 | 34 | 12.79 | 70.030 | <0.001 |

| No | 419 | 58.85 | 232 | 87.21 | |||

| Fecal property | Watery stool | 582 | 81.74 | 126 | 47.37 | 159.234 | <0.001 |

| Mucoid stool | 102 | 14.33 | 98 | 36.84 | |||

| Rice water stool | 22 | 3.09 | 4 | 1.50 | |||

| Blood stool | 6 | 0.84 | 38 | 14.29 | |||

| Use antibiotics before hospitals | Yes | 18 | 2.53 | 8 | 3.01 | 0.172 | 0.678 |

| No | 694 | 97.47 | 258 | 96.99 | |||

| Diarrhea days before hospitals | ≤3 days | 480 | 67.42 | 156 | 58.65 | 6.548 | 0.010 |

| >3 days | 232 | 32.58 | 110 | 41.35 | |||

| Diarrhea times/per day | ≤5 times | 366 | 51.4 | 179 | 67.29 | 19.861 | <0.001 |

| 6–10 times | 303 | 42.56 | 77 | 28.95 | |||

| >10 times | 43 | 6.04 | 10 | 3.76 | |||

| Vomit days before hospitals | ≤3 days | 277 | 95.18 | 30 | 90.91 | 1.092 | 0.296 |

| >3 days | 14 | 4.82 | 3 | 9.09 | |||

| Vomit times/per day | ≤5 times | 232 | 79.73 | 28 | 84.85 | 0.571 | 0.450 |

| >5 times | 59 | 20.27 | 5 | 15.15 | |||

Fecal samples detection

Samples were collected from 2013–2016, and details of the distribution in each year were shown in Table 2. Toxin genes tcdA and/or tcdB were found in 138/978 cases (Supplementary file 1, S1), and the total positive rate was 14.11% for fecal samples virulence genes (Table 2). Among them, 118 cases (85.51%) were tcdA+/tcdB+, 7 cases (5.07%) were tcdA+/tcdB−, and 13 cases (9.42%) were tcdA−/tcdB+ (S1). In addition, three cdtA+/cdtB+ positive cases from hospital D were found in this study and the rest were negative for binary toxins genes (S1). For 138 positive cases, 91 was tcdC+, 124 were tcdR+, and 122 were tcdE+. Among the 138 positive virulence gene samples, 102 cases (73.91%) were from children, only 36 (26.09%) cases from adults. However, the positive samples of children was 14.33% (102/712) and 13.53% (36/266) for adults, showing no statistical significance (χ2 = 0.100, P = 0.752). As showed in Table 2, the clinical features of children group were quite similar, such as 46.08% cases had fever and vomit, 83.33% patients had watery stool, 65.69% of cases had diarrhea over 3 days, 93.48% of children patients had vomit more than 3 days, and 76.09% cases with vomit frequency less than 5 times. Furthermore, all these clinical features of children group showed no statistical difference (P > 0.05). While, for adults, the distributions of sentinel hospitals (χ2 = 6.250, P = 0.012), fecal property (χ2 = 11.721, P = 0.008), duration of diarrhea (χ2 = 6.702, P = 0.010) had statistical significance. Compared with children cases, most of the positive cases of adults were from hospital D (86.11%), and the blood stool in adult cases (27.78%) had a relative high proportion. Around 61.11% patients had diarrhea over 3 days. Logistic analysis showed that fever (OR = 2.776, 95%CI = 1.342–5.742, P = 0.006) was the risk factor for positive virulence genes of fecal samples. Other clinical characteristics showed no statistical significance (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of the fecal samples virulence gene and isolation results between children and adults groups

| Age groups | Factors | Virulence genes* | χ2 | P value | Isolation results | χ2 | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (cases) | % | Negative (cases) | % | Positive (cases) | % | Negative (cases) | % | ||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Children | Male | 68 | 66.67 | 379 | 62.13 | 0.769 | 0.380 | 26 | 60.47 | 421 | 62.93 | 0.105 | 0.746 |

| Female | 34 | 33.33 | 231 | 37.87 | 17 | 39.53 | 248 | 37.07 | |||||

| Adults | Male | 17 | 47.22 | 120 | 52.17 | 0.306 | 0.580 | 5 | 41.67 | 132 | 51.97 | 0.487 | 0.485 |

| Female | 19 | 52.78 | 110 | 47.83 | 7 | 58.33 | 122 | 48.03 | |||||

| Sentinel hospitals | |||||||||||||

| Children | A | 13 | 12.75 | 130 | 21.31 | 7.118 | 0.068 | 6 | 13.95 | 137 | 20.48 | 2.058 | 0.561 |

| B | 59 | 57.84 | 352 | 57.70 | 29 | 67.44 | 382 | 57.10 | |||||

| C | 14 | 13.73 | 72 | 11.80 | 5 | 11.63 | 81 | 12.11 | |||||

| D | 16 | 15.68 | 56 | 9.19 | 3 | 6.98 | 69 | 10.31 | |||||

| Adults | A | 5 | 13.89 | 80 | 34.78 | 6.250 | 0.012 | 0 | 0.00 | 85 | 33.46 | 5.902 | 0.015 |

| B | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | — | — | — | — | |||||

| C | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | — | — | — | — | |||||

| D | 31 | 86.11 | 150 | 65.22 | 12 | 100 | 169 | 66.54 | |||||

| Departments | |||||||||||||

| Children | Internal Medicine | 41 | 40.20 | 254 | 41.64 | 0.075 | 0.784 | 13 | 30.23 | 282 | 42.15 | 2.366 | 0.124 |

| Pediatric Clinic | 61 | 59.80 | 356 | 58.36 | 30 | 69.77 | 387 | 57.85 | |||||

| Adults | Internal Medicine | 36 | 100 | 230 | 100 | — | — | 12 | 100 | 254 | 100 | — | — |

| Pediatric Clinic | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Years | |||||||||||||

| Children | 2013 | 14 | 13.73 | 130 | 21.31 | 5.539 | 0.136 | 9 | 20.93 | 135 | 20.18 | 9.237 | 0.026 |

| 2014 | 52 | 50.98 | 283 | 46.39 | 17 | 39.53 | 318 | 47.53 | |||||

| 2015 | 28 | 27.45 | 172 | 28.20 | 11 | 25.58 | 189 | 28.25 | |||||

| 2016 | 8 | 7.84 | 25 | 1.04 | 6 | 13.96 | 27 | 4.04 | |||||

| Adults | 2013 | 4 | 11.11 | 28 | 12.17 | 1.440 | 0.487 | 4 | 33.33 | 28 | 11.02 | 5.983 | 0.066 |

| 2014 | 31 | 86.11 | 183 | 79.57 | 8 | 66.67 | 206 | 81.10 | |||||

| 2015 | 1 | 2.78 | 19 | 8.26 | 0 | 0.00 | 20 | 7.88 | |||||

| 2016 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Fever | |||||||||||||

| Children | Yes | 47 | 46.08 | 248 | 40.66 | 1.059 | 0.303 | 19 | 44.19 | 276 | 41.26 | 0.143 | 0.705 |

| No | 55 | 53.92 | 362 | 59.34 | 24 | 55.81 | 393 | 58.74 | |||||

| Adults | Yes | 2 | 5.56 | 22 | 9.57 | 0.610 | 0.435 | 0 | 0.00 | 24 | 9.45 | 1.246 | 0.264 |

| No | 34 | 94.44 | 208 | 90.43 | 12 | 100 | 230 | 90.55 | |||||

| Vomit | |||||||||||||

| Children | Yes | 47 | 46.08 | 246 | 40.33 | 1.193 | 0.275 | 28 | 65.12 | 265 | 39.61 | 10.853 | 0.001 |

| No | 55 | 53.92 | 364 | 59.67 | 15 | 34.88 | 404 | 60.39 | |||||

| Adults | Yes | 3 | 8.33 | 31 | 13.48 | 0.739 | 0.390 | 0 | 0.00 | 34 | 13.39 | 1.842 | 0.175 |

| No | 33 | 91.67 | 199 | 86.52 | 12 | 100 | 220 | 86.61 | |||||

| Fecal property | |||||||||||||

| Children | Watery stool | 85 | 83.33 | 497 | 81.48 | 5.174 | 0.159 | 37 | 86.04 | 545 | 81.46 | 1.908 | 0.592 |

| Mucoid stool | 17 | 16.67 | 85 | 13.93 | 6 | 13.96 | 96 | 14.35 | |||||

| Rice water stool | 0 | 0.00 | 22 | 3.61 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 3.29 | |||||

| Blood stool | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 0.98 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0.90 | |||||

| Adults | Watery stool | 12 | 33.33 | 114 | 49.57 | 11.721 | 0.008 | 4 | 33.33 | 122 | 48.03 | 8.091 | 0.044 |

| Mucoid stool | 12 | 33.33 | 86 | 37.39 | 3 | 25.00 | 95 | 37.40 | |||||

| Rice water stool | 2 | 5.56 | 2 | 0.87 | 1 | 8.34 | 3 | 1.18 | |||||

| Blood stool | 10 | 27.78 | 28 | 12.17 | 4 | 33.33 | 34 | 13.39 | |||||

| Use antibiotics before hospitals | |||||||||||||

| Children | Yes | 3 | 2.94 | 15 | 2.46 | 0.082 | 0.774 | 2 | 4.65 | 16 | 2.39 | 0.837 | 0.360 |

| No | 99 | 97.06 | 595 | 97.54 | 41 | 95.35 | 653 | 97.61 | |||||

| Adults | Yes | 1 | 2.78 | 7 | 3.04 | 0.008 | 0.931 | 0 | 0.00 | 8 | 3.15 | 0.390 | 0.532 |

| No | 35 | 97.22 | 223 | 96.96 | 12 | 100 | 246 | 96.85 | |||||

| Diarrhea days before hospitals | |||||||||||||

| Children | ≤3 days | 67 | 65.69 | 413 | 67.7 | 0.162 | 0.687 | 24 | 55.81 | 456 | 68.16 | 2.804 | 0.094 |

| >3 days | 35 | 34.31 | 197 | 32.30 | 19 | 44.19 | 213 | 31.84 | |||||

| Adults | ≤3 days | 14 | 38.89 | 142 | 61.74 | 6.702 | 0.010 | 3 | 25.00 | 153 | 60.24 | 5.866 | 0.015 |

| >3 days | 22 | 61.11 | 88 | 38.26 | 9 | 75.00 | 101 | 39.76 | |||||

| Diarrhea times/per day | |||||||||||||

| Children | ≤5 times | 59 | 57.84 | 307 | 50.33 | 3.502 | 0.174 | 29 | 67.44 | 337 | 50.37 | 9.686 | 0.008 |

| 6–10 times | 35 | 34.31 | 268 | 43.93 | 9 | 20.93 | 294 | 43.95 | |||||

| >10 times | 8 | 7.85 | 35 | 5.74 | 5 | 11.63 | 38 | 5.68 | |||||

| Adults | ≤5 times | 26 | 72.22 | 153 | 66.52 | 3.766 | 0.152 | 11 | 91.67 | 168 | 66.14 | 3.427 | 0.180 |

| 6–10 times | 7 | 19.44 | 70 | 30.43 | 1 | 8.33 | 76 | 11.36 | |||||

| >10 times | 3 | 8.34 | 7 | 3.05 | 0 | 0.00 | 10 | 22.50 | |||||

| Vomit days before hospitals | |||||||||||||

| Children | ≤3 days | 43 | 93.48 | 234 | 95.51 | 0.349 | 0.555 | 24 | 88.89 | 235 | 95.53 | 2.579 | 0.108 |

| >3 days | 3 | 6.52 | 11 | 4.49 | 3 | 11.11 | 11 | 4.47 | |||||

| Adults | ≤3 days | 3 | 100 | 27 | 90.00 | 0.330 | 0.566 | 0 | 0.00 | 30 | 90.91 | — | — |

| >3 days | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 10.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 9.09 | |||||

| Vomit times/per day | |||||||||||||

| Children | ≤5 times | 35 | 76.09 | 196 | 80.33 | 0.372 | 0.542 | 21 | 75.00 | 213 | 80.38 | 0.455 | 0.500 |

| >5 times | 11 | 23.91 | 48 | 19.67 | 7 | 25.00 | 52 | 19.62 | |||||

| Adults | ≤5 times | 3 | 100 | 26 | 83.87 | 0.567 | 0.451 | 0 | 0.00 | 29 | 85.29 | — | — |

| >5 times | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 16.13 | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 14.71 | |||||

*The positive virulence gene indicated that at least one of tcdA or tcdB was positive.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of clinical features for virulence genes detection and culture results.

| Factors | Virulence genes of fecal sample results | Isolation results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%C.I. | P value | OR | 95%C.I. | P value | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age group | 1.463 | 0.313 | 6.835 | 0.629 | 1.050 | 0.110 | 2.091 | 0.998 |

| Sentinel hospitals | 0.396 | 0.213 | 0.734 | 0.003 | 0.802 | 0.344 | 1.868 | 0.608 |

| Departments | 0.647 | 0.240 | 1.745 | 0.390 | 0.655 | 0.205 | 2.092 | 0.475 |

| Sex | 1.338 | 0.652 | 2.748 | 0.428 | 0.802 | 0.333 | 1.934 | 0.623 |

| Years | 0.690 | 0.462 | 1.029 | 0.068 | 0.681 | 0.418 | 1.111 | 0.124 |

| Fever | 2.776 | 1.342 | 5.742 | 0.006 | 1.166 | 0.491 | 2.767 | 0.728 |

| Fecal property | 0.961 | 0.495 | 1.865 | 0.906 | 1.083 | 0.419 | 2.798 | 0.870 |

| Use antibiotics before hospitals | 0.898 | 0.713 | 4.670 | 0.898 | 1.077 | 0.109 | 10.591 | 0.950 |

| Diarrhea days before hospitals | 0.895 | 0.454 | 1.761 | 0.747 | 0.806 | 0.340 | 1.912 | 0.625 |

| Diarrhea times/per day | 1.280 | 0.764 | 2.144 | 0.349 | 1.586 | 0.799 | 3.146 | 0.187 |

| Vomit days before hospitals | 1.304 | 0.314 | 5.421 | 0.715 | 0.373 | 0.084 | 1.654 | 0.194 |

| Vomit times/per day | 0.767 | 0.342 | 1.720 | 0.520 | 0.713 | 0.261 | 1.948 | 0.510 |

Bacterial culture, toxin profile and PCR ribotyping

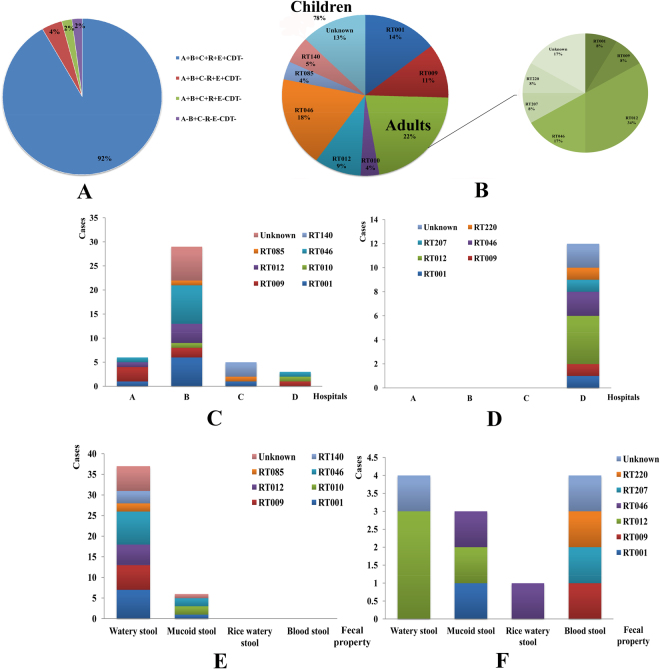

Fifty-five C. difficile strains were isolated from 978 fecal samples and the isolation rate was 5.62% (Table 2). For all these isolates, 48 strains (87.27%) were toxigenic, and seven strains were non-toxigenic (S1). Except one tcdA−/tcdB+ (YNCD695) strain from pediatric case in hospital B, other strains were tcdA+/tcdB+ (Table 2). For the toxigenic C. difficile, 45 strains were positive for tcdC, 47 were tcdR+, and 46 were tcdE+ (S1). The binary toxin genes cdtA/cdtB were negative for all the isolates (S1). Four toxin profiles were identified: A+B+C+R+E+CDT−, A+B+C−R+E+CDT− (YNCD169 and 175), A+B+C+R+E−CDT− (YNCD222) and A−B+C−R−E−CDT− (YNCD695) (Fig. 1A). This indicated significant diversity in PaLoc area and warranted further deep exploration by amplifying the whole length of the PaLoc region.

Figure 1.

The toxin profiles and PCR ribotyping characters of C. difficile between children and adults in this study. (A) The toxin profile of isolated strains. (B) RT constituent ratio of C. difficile strains. Left: children group; right: adults group. (C) RT distribution characters of C. difficile for different hospitals in children group. (D) RT distribution characters of C. difficile for different hospitals in adults group. (E). RT distribution characters of C. difficile for fecal property in children group. (F) RT distribution characters of C. difficile for fecal property in adults group.

Among the 55 strains, 43 (78.18%) were isolated from children, 12 (21.22%) were isolated from adults. The isolation rates between two groups (6.04% for children; 4.51% for adults) showed no statistical difference (χ2 = 0.852, P = 0.356). Similar with fecal samples’ results, in children group, 60.47% were male and 67.44% were from hospital B. 44.19% cases had fever, 86.04% patients had watery stool, 55.81% of cases had diarrhea days no more than 3 days. 88.89% of children patients vomited less than 3 days, and 75.00% cases had vomiting frequency no more than 5 times/per day. All these clinical features of children group showed no statistical difference (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 2. However, the distribution of isolated years (χ2 = 9.237, P = 0.026), vomit (χ2 = 10.853, P = 0.001) and diarrhea times/per day (χ2 = 9.686, P = 0.008) showed statistical difference for children group according to bacterial culture results. For adults group, isolation rate of sentinel hospitals (χ2 = 5.902, P = 0.015), fecal property (χ2 = 8.091, P = 0.044), and diarrhea duration days before hospital treatment (χ2 = 5.866, P = 0.015) had statistical significance. All the C. difficile strains were isolated from hospital D, 33.33% cases had blood stool, and 75.00% of patients had diarrhea over 3 days (Table 2). Logistic regression analysis showed that all the clinical features had no statistical difference with bacterial culture results (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

A total of 9 RT types were identified, and the details were as follows: 9 isolates of RT001, 7 of RT009, 2 of RT010, 9 of RT012, 12 of RT046, 2 of RT085, 3 of RT140, 1 of RT207, 1 of RT220, and the rest 9 isolates were non-classified by the standard RT library (Fig. 1B). Notably, no hypervirulent RT027 or RT078 were found in this study. 10 (10/43, 23.26%) strains of RT046, 8 (8/43, 18.60%) of RT001, and 6 (6/43, 13.95%) of RT009 were found in children group, accounted for 55.81%. While, in adults group, 4 (4/12, 33.33%) strains of RT012 and 2 (2/12, 16.67%) of RT046 were the most RT types (Fig. 1B). The distribution of RT types had no statistical significance with children and adults groups (χ2 = 12.847, P = 0.170). For children patients, RT types showed statistical significance with sentinel hospitals (χ2 = 46.717, P = 0.001), departments of hospitals (χ2 = 16.766, P = 0.019) and fecal property (χ2 = 15.247, P = 0.033). All the RT types could be found in hospital B, except for RT140, RT207 and RT220. Among them, RT046 (8 cases) and RT001 (6 cases) were the most prevalent types, as shown in Fig. 1C. Furthermore, most RT types of patients had watery stool (Fig. 1E). For adults cases, all the clinical features showed no difference with RT types of isolates (P > 0.05). The correlation analysis between RT types and clinical features of patients showed that sentinel hospitals (r = 0.281, P = 0.038), departments of hospitals (r = −0.283, P = 0.036) and fecal property (r = 0.361, P = 0.007) had statistical significance, others had no correlations.

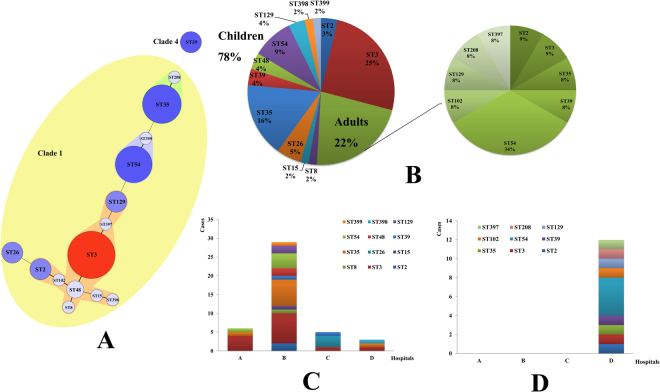

MLST

MLST results showed that 55 C. difficile formed 15 ST types, with a high degree of discrete characteristics (S1). Three novel STs were identified in our study (S1). The toxin profile of ST397 and 399 was the same (positive for tcdA, tcdB, tcdC, tcdR, tcdE), while for ST398, all these genes were negative. ST3 (15 cases, 27.27%), ST35 (10 cases, 18.18%) and ST54 (9 cases, 16.36%) were the most common ST types, as shown in Fig. 2A. Except ST39 belonging to evolutionary MLST clade 4, all other ST types belonged to the large heterogeneous clade 1 (Fig. 2A yellow area). The distribution of ST types had no statistical significance with children and adults groups (χ2 = 19.500, P = 0.147). 14 (14/43, 32.56%) strains of ST3, 9 (9/43, 20.93%) of ST35, and 5 (5/43, 11.63%) of ST54 were mainly types found in children group, accounted for 65.12%. While, in adults group, 4 (4/12, 33.33%) strains of ST54 was the most dominant ST types (Fig. 2B). For children patients, ST types showed statistical significance with sentinel hospitals (χ2 = 48.766, P = 0.038). Similar with the RT types results, most of the ST types distributed in hospital B, except ST26, ST102, ST208, ST397 and ST398. Among them, ST3 (8 cases) and ST35 (7 cases) were the most distributed types, as shown in Fig. 2C. Other clinical features of children patients had no difference with MLST types (P > 0.05). For adults cases, all the clinical characteristics showed no difference with ST types (P > 0.05). The correlation analysis between ST types and clinical features of patients showed that sentinel hospitals (r = 0.302, P = 0.025) had statistical significance, others had no correlations.

Figure 2.

The minimum spanning tree and ST types distribution characters of C. difficile between children and adults in this study. (A) The minimum spanning tree of isolated C. difficile for MLST typing. Each circle corresponds to ST types, the number of which is indicated for the size of circles. The yellow color area belong to the Clade 1. The lines between circles indicate the similarity between profiles (bold, 5 alleles in common; normal, 4 alleles; dotted, ≤3 alleles). (B) ST constituent ratio of C. difficile strains. Left: children group; right: adults group. (C) The distribution characters of C. difficile ST types for different hospitals in children group. (D) The distribution characters of C. difficile ST types for different hospitals in adults group.

The ST and RT genotypes had a general agreement, high correlation were revealed in ST35/RT046 (10 cases, 18.18%), ST54/RT012 (8 cases, 14.55%), ST3/RT001 (8 cases, 14.55%) and ST3/RT009 (7 cases, 12.73%), which accounted for 60.00% of all the isolates. The ST and RT genotypes showed statistical significance in both children (χ2 = 246.206, P < 0.001) and adults groups (χ2 = 72.00, P = 0.014). ST35/RT046 (9/43, 20.93%), ST3/RT001 (8/43, 18.60%) and ST3/RT009 (6/43, 13.95%) were the commonly found genotype profiles in children group, while the most genotype in adults group was ST54/RT012 (4/12, 33.33%).

Co-infection with other enteric pathogens

In addition to confirming C. difficile infection, we also screened the stool samples for other intestinal pathogens15–17. A diverse collection of pathogens were detected including diarrheagenic E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, rotavirus, calicivirus, astrovirus and adenovirus. Finally, 16 stool samples with positive toxin genes were also found co-exist with one/two other pathogens mentioned above. Details were summarized in supplementary file 1. All 16 samples were positive for tcdA and tcdB, and negative for cdtA/B, except for sample YNCD 654 and 659, which were tcdA negative but tcdB positive. Sample YNCD550 was detected positive of both diarrheagenic E. coli and rotavirus (S1). The age of sample YNCD306 was 45-year-old, and the age of the rest 15 samples were no more than 2-year-old. Three cases (YNCD550, 822, and 831) had co-infection with rotavirus, 13 cases had co-infection with diarrheagenic E. coli, and one case (YNCD601) had co-infection with non-typhoidal Salmonella (S1). According to the bacterial culture result, 6 strains (patients) were found co-infected with diarrheagenic E. coli, non-typhoidal Salmonella and rotavirus. Among them, one case (YNCD831) had co-infection with rotavirus; four cases had co-infection with diarrheagenic E. coli and one case (YNCD601) had co-infection with non-typhoidal Salmonella (S1). The age of these 6 patients were no more than 2-year-old. Furthermore, two C. difficile strains (YNCD399 and YNCD591) were non-toxigenic, others were toxigenic isolates.

Analyzed with the co-infections, 16 cases of positive virulence genes were excluded, 122 cases (12.47%) were CA-CDI for virulence genes detection. For bacterial cultures, 6 cases were excluded for co-infection, and 5 non-toxigenic strains were also excluded, only 44 cases (4.50%) were CA-CDI for isolations.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first cross-sectional study of CA-CDI in southwest China to address both clinical features and molecular characteristics of C. difficile. It is known that C. difficile is found in 30–35% newborns and in 10–15% infants up to 2 years as a commensal bacterium18–20, but is potentially harmful for children above two years5. Although C. difficile isolated from an infant under 2 years is normally considered as colonization, we still pay attention to pediatric CDI in this age group if clinical symptoms are typical, or other common intestinal pathogens or physiological diarrhea are excluded. Therefore, we detected toxin genes in all these age groups, and found similar positive isolated rates in both stool samples (14.33% for children, and 13.53% for adults) and isolates (6.04% for children, and 4.51% for adults) between children and adults. The presence of bloody diarrhea was considered as severe CDI for both children and adults21. In contrast to studies reported21–24, in which a higher proportion of severe CDI in children than that in adult was found, adult patients with bloody diarrhea (38/44 = 86.36%) were much larger than pediatric patients (6/44 = 13.64%) in this study. This might be attributed to lacking of mature toxin binding receptors on epithelial cells, or in complete cellular uptake of the toxins and/or protecting microbiome composition of infants, which leading to insensitive to free C. difficile toxins in the intestinal tract22,25. Antibiotics are usually considered as a risk factor, but not as a prerequisite for developing CDI. A previous study showed that nearly 30% of patients with CA-CDI did not receive antibiotics in the 12 weeks prior to infection11. Here, only 2.7% of patients received antibiotics before admission treatment in hospitals.

According to PCR detection of tcdA/tcdB of stool samples, 138 samples were positive. Furthermore, 55 isolates were successfully cultured, including 7 non-toxigenic strains which might be missed if only tcdA/tcdB positive stool samples were cultured. The average isolation rate (5.62%), and the positive rate (14.11%) for fecal virulence genes in this study was similar with previous studies. A study in United Kingdom illustrated the incidence of CA-CDI increased from 0 to 18 cases per 100,000 persons per year between 1994 and 200426. Data from North America and Europe suggest that 20–27% of all CDI cases are community-associated, with an incidence of 20–30 per 100,000 population27. A large study in the Netherlands displayed that the proportion of positive toxin fecal samples (1.5% of 2,443 samples) was remarkably similar to that seen in the UK study by examining all fecal samples using a toxin EIA28.

In China, reports on community-acquired CDI were extremely rare. There is only one case of community-acquired CDI, due to a moxifloxacin susceptible RT 027 strain documented in China29. Although RT078 was recognized as key pathogen causing CA-CDI, especially in younger adults without hospital contact, but no RT 078 nor 027 were identified here. It was reported that susceptible populations and molecular types of hospital acquired CDI and CA-CDI were distinct. A Europe-wide survey of CDI in 2008 showed that ribotypes 014/020 (15%), 001 (10%), and 078 (8%) were most prevalent; the prevalence of ribotype 027 was 5%30. While in another study in North China, ST54 was the dominant type and accounted for 29.2% (66/226) and the other most frequent types were ST3 (25.7%), ST2 (9.7%), ST35 (10.6%), and ST37 (8.4%), but they displayed distinct proportions in diarrhea adults, healthy infant and healthy adults31. Similarly, ST3, ST35 and ST54 were the major ST types in our study with different composition rate among diarrhea infants (32.56%, 20.93% and 11.63%) and diarrhea adults (8.33%, 8.33% and 33.33%). However, ST37, previously reported dominant types in China from some studies32–34 was not found in this study, which may due to divergence of geography, population, habits and customs. A recent study of hospitalized C. difficile infection conducted in Eastern China13 showed that ST37/RT017 (16.5%) was the most dominant genotype. RT001 (14.4%), RT012 (13.4%), RT017 (16.6%) and ST2 (11.2%), ST3 (16.3%), ST37 (16.6%), ST54 (12.9%) were predominant. Interestingly, the genotypes profiles in our study were a little bit distinct from that report. ST35/RT046, ST3/RT009 and ST3/RT001 were most common genotypes for pediatric patients, while the most genotype of adult patients was ST54/RT012 in our study.

According to the MLST scheme, almost all isolates clustered in clade 1, and only 3 isolates (ST39) were in clade 4 in this study. The C. difficile population structure consists of six distinct phylogenetic clades designated 1–5 and C-I35,36, and the latter one was highly divergent, entirely nontoxigenic, and potentially a new species or subspecies of C. difficile37. Clade 1 is a highly heterogeneous cluster with toxigenic and nontoxigenic STs and RTs, in North American and Europe35. Interestingly, the ST /RT types mentioned above were not the dominant ones in our study, and ST35/RT046, ST3/RT001, ST3/RT009 and ST54/RT012 took highest proportion here. The most notable types in clade 4 is ST 37 (RT017), which has been associated with outbreaks in Europe38,39, North America40, and Argentina41, and is responsible for much of the CDI burden in Asia42. However, no ST 37 was identified, leading to focus on clade 4 (containing ST 39 in this study) in China in following research. This further emphasized the importance of national wide surveillance of CDI in China.

This study was the first systemic surveillance for CA-CDI, included children and adults cases in southwest China, in which the prevalence and risk factors were determined. Detailed clinical information and laboratory tests were collected and performed to identify the molecular and epidemiological characteristics of CA-CDI in this area. This study gave us an eye on CA-CDI and caused attention focused on CDI surveillance in China. However, it was indentified several limitations in this study. Firstly, the study was conducted in an urban region that probably showed a poor representation of the potential CA-CDI. Secondly, the diarrhea cases were selected from outpatient cases. But the patients who did not to seek medical advice were not recruited. Thirdly, some of the specific information of C. difficile infection probably missed when data collections, such as co-morbidities, exposure to proton-pump inhibitors and histamine-2 antagonists etc. Therefore, further research involved diarrhea cases from urban, rural, outpatient from hospital, and patients from other medical facilities might be done to evaluate the prevalence, clinical features and burdens of C. difficile infection.

Methods

Patients and case definitions

978 diarrhea cases were collected from January 2013 to March 2016 in four sentinel hospitals in Yunnan Province, southwest China. The fecal samples were continuously collected for each month during that period. The sentinel hospitals were Puji Community Health Service Center (hospital A), Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (hospital B), Kunming Children’s Hospital (hospital C), and First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (hospital D). Hospital B to D were tertiary care academic medical center in southwest China, and hospital A was a primary health service center. These four hospitals covered the entire Kunming area. The majority of diarrhea patients came from 12 districts in Kunming, and other cities in Yunnan province, while the rest of patients were from Sichuan or Guizhou provinces in southwest China. The stool specimens from diarrhea patients during the study period were collected and transported to the Yunnan Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. To avoid overrepresentation, only the first stool specimen from each patient was included.

Diarrhea was defined as more than 3 times/per day, accompanied by changes in fecal traits (loose, watery or unformed stool)43. Clinical information of patients were collected when they came to hospitals, including gender, age, manifestations et al. Patients <18 years was considered as children, ≥18 years were adults. All these cases were defined as community-acquired diarrhea, indicated that the onset of diarrhea symptoms occurring while the patient was outside a healthcare facility, or the patient had no prior stay in a healthcare facility within the 12 weeks prior to symptom onset44,45. Therefore, all the C. difficile detection positive cases (stool specimens of virulence genes and bacterial isolations) in this study were defined as community-acquired C. difficile infection (CA-CDI).

Previous to C. difficile detection, the intestinal pathogen spectrums were conducted for all the stool specimens, including diarrheagenic E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, rotavirus, calicivirus, astrovirus and adenovirus15–17. We analyzed the co-infection results between C. difficile and other enteric pathogens mentioned above.

Detection of virulence genes in fecal samples

DNA extraction was performed on all fecal samples using a fecal sample DNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing) based on the manufacturers’ instruction. The DNA samples were stored at −20 °C and tested for the presence of virulence genes tcdA, tcdB, tcdC, tcdR, tcdE, cdtA and cdtB, using primers shown in Table 4. PCR amplification was performed using 20 μl system, 10 μl of Taq premix, 8 μl of water, 0.5 μl of upstream and downstream primers (10 μmol), and 1 μl of template DNA. The amplification reactions were: 94 °C for 5 min; 94 °C 15 sec, 55 °C 30 sec, 72 °C 30 sec, 30 cycles, and finally at 72 °C for 10 min. The products were observed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and gel imager (Bio-Rad, GelDoc).

Table 4.

PCR primers used in this study.

| Genes | Primers | Sequences (5′–3′) | Amplification length |

|---|---|---|---|

| tcdA | tcdA-F | GGACATGGTAAAGATGAATTC | 546 bp |

| tcdA-R | CCCAATAGAAGATTCAATATTAAGCTT | ||

| tcdB | tcdB-F | GTGTAGCAATGAAAGTCCAAGTTTACGC | 204 bp |

| tcdB-R | CACTTAGCTCTTTGATTGCTGCACCT | ||

| tcdC | tcdC-F | TCTCTACAGCTATCCCTGGT | 673 bp |

| tcdC-R | AAAAATGAGGGTAACGAATTT | ||

| tcdR | tcdR-F | CTCAGTAGATGATTTGCAAGAA | 473 bp |

| tcdR-R | TTTTAAATGCTCTATTTTTAGCC | ||

| tcdE | tcdE-F | AGGAGGCGTTATGAATATGA | 358 bp |

| tcdE-R | TGGTAATCCACATAAGCACA | ||

| cdtA | cdtA-F | TGAACCTGGAAAAGGTGATG | 375 bp |

| cdtA-R | AGGATTATTTACTGGACCATTTG | ||

| cdtB | cdtB-F | CTTAATGCAAGTAAATACTGAG | 510 bp |

| cdtB-R | AACGGATCTCTTGCTTCAGTC | ||

| 16SrRNA | 27 F | AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | 1465 bp |

| 1492 R | TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT | ||

| 16–23 S rDNA | PRB | GTGCGGCTGGATCACCTCCT | variable |

| PRBas | CCCTGCACCCTTAATAACTTGACC | ||

| adk | adk-P1 | GCTATGGTGCCAGCTCTTAC | 1500 bp |

| adk-P2 | GACCAGGTGAGCCTACTATG |

Bacterial culture

Stool specimens from diarrhea patients were collected using Transwabs (MW&E Ltd., Wiltshire, England), and stored in brain heart infusion (BHI, Oxoid, UK) with 15% glycerol in −80 °C. All faces specimens were inoculated on selective cycloserine-cefoxitin-fructose agar plates (CCFA, Oxoid, UK) with 5% egg yolk after ethanol shock treatment and incubated in an anaerobic jar (80% nitrogen, 10% hydrogen and 10% carbon dioxide) (Mart, NL) at 37 °C for 48 h. C. difficile colonies were identified on the basis of their typical morphology and Gram stain as well as the characteristic odour. Suspected colonies were further confirmed by API 20 A (BioMerieux, France) on their biochemical characteristics and 16 SrRNA gene with primer shown in Table 4.

Bacterial DNA isolation, PCR-ribotyping and toxin gene profiling

Crude bacterial template DNA for toxin profiling was prepared by resuspension of cells in a 5% (wt/vol) solution of Chelex-100 resin (Bio-Rad). All isolates were screened by PCR for the presence of the toxin A (tcdA) and toxin B (tcdB) genes and the binary toxin (cdtA and cdtB) genes46,47 and the regulating genes of tcdC, tcdR, and tcdE. PCR ribotyping was performed as previously described48. PCR ribotyping reaction products were concentrated using a Qiagen Min-Elute PCR purification kit (QIAGEN) and run on a QIAxcel capillary electrophoresis platform (QIAGEN). Visualization of PCR products was performed with QIAxcel ScreenGel software (v1.3.0; QIAGEN). PCR ribotyping banding patterns were identified by comparison of banding patterns with a reference library consisting of a collection of 24 reference strains from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), and a collection of 30 isolates from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Interpretation of the capillary electrophoresis data (PCR ribotyping banding patterns) was performed using the BioNumerics software package v.7.6 (Applied Maths, Saint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). Isolates that could not be identified with the available reference library were designated with internal nomenclature.

Multilocus sequence typing

MLST was performed on all recovered isolates using the primers and methods developed by Griffiths et al.49. Seven housekeeping genes (adk, atpA, dxr, glyA, recA, sodA and tpi) were amplified and products were sent for bidirectional sequencing to TaKaRa, Japan. The complete allele sequences were analyzed using DNAStar and MEGA4 software and allele and ST assignments were performed using the C. difficile database at pubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/cdifficile). A minimum spanning tree was created using BioNumerics version 7.6. During the experiment, adk gene for seven strains couldn’t amplified, and we re-designed the primer (Table 4) based on the Clone Manager Professional Suite 8 software.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by IBM SPSS software (version 19.0 for Windows, Armonk, NY). Univariate analysis was performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent risk factors. Kruskal-Wallis and χ2 test were used to analyze correlation among RTs, STs and clinical features of strains. Odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), and P values were calculated to assess the differences between groups. Two-sided significance was assessed for all variables, applying a cut-off value of P < 0.05.

Ethics statements

The human sample collection and detection protocols were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Review Committee [Institutional Review Board (IRB)] of National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. All adult subjects provided informed consent, and a parent or guardian of any child participant provided informed consent on their behalf.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Thomas V. Riley and Daniel R. Knight from University of Western Australia for proof reading and critical revision of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

W.X., J.L. and Y.W. conceived and designed the experiments; F.L., W.L., W.Z. and X.L. performed the experiments; W.G. and X.F. performed the statistical analysis; F.L. and W.G. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Feng Liao, Wenge Li and Wenpeng Gu contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-21762-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuan Wu, Email: wuyuan@icdc.cn.

Jinxing Lu, Email: lujinxing@icdc.cn.

References

- 1.Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:526–536. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dingle KE, et al. Clinical Clostridium difficile: clonality and pathogenicity locus diversity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang C, et al. The incidence and drug resistance of Clostridium difficile infection in Mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37865. doi: 10.1038/srep37865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinlen L, Ballard JD. Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:247–252. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e939d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman J, et al. The changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:529–549. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00082-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surveillance for community-associated Clostridium difficile--Connecticut, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep57, 340–343, doi:mm5713a3 [pii] (2008). [PubMed]

- 7.Wilcox MH, Mooney L, Bendall R, Settle CD, Fawley WN. A case-control study of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:388–396. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voth DE, Ballard JD. Clostridium difficile toxins: mechanism of action and role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:247–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.247-263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goorhuis A, et al. Emergence of Clostridium difficile infection due to a new hypervirulent strain, polymerase chain reaction ribotype 078. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1162–1170. doi: 10.1086/592257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim SK, et al. Emergence of a ribotype 244 strain of Clostridium difficile associated with severe disease and related to the epidemic ribotype 027 strain. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1723–1730. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chitnis AS, et al. Epidemiology of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection, 2009 through 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Jumaili IJ, Shibley M, Lishman AH, Record CO. Incidence and origin of Clostridium difficile in neonates. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:77–78. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.1.77-78.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin D, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile Infection in Hospitalized Patients in Eastern China. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:801–810. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01898-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng JW, et al. Molecular Epidemiology and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Clostridium difficile Isolates from a University Teaching Hospital in China. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1621. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, et al. Epidemiology and genetic diversity of group A rotavirus in acute diarrhea patients in pre-vaccination era in southwest China. J Med Virol. 2017;89:71–78. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang SX, et al. Impact of co-infections with enteric pathogens on children suffering from acute diarrhea in southwest China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:64. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0157-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang SX, et al. Case-control study of diarrheal disease etiology in individuals over 5 years in southwest China. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:58. doi: 10.1186/s13099-016-0141-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Feghaly RE, Tarr PI. Editorial commentary: Clostridium difficile in children: colonization and consequences. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:9–12. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheepers LE, et al. The intestinal microbiota composition and weight development in children: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:16–25. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enoch DA, Butler MJ, Pai S, Aliyu SH, Karas JA. Clostridium difficile in children: colonisation and disease. J Infect. 2011;63:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz KL, Darwish I, Richardson SE, Mulvey MR, Thampi N. Severe clinical outcome is uncommon in Clostridium difficile infection in children: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jangi S, Lamont JT. Asymptomatic colonization by Clostridium difficile in infants: implications for disease in later life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:2–7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d29767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karaaslan A, et al. Hospital acquired Clostridium difficile infection in pediatric wards: a retrospective case-control study. Springerplus. 2016;5:1329. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khanna S, et al. The epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in children: a population-based study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1401–1406. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonara S, Leber AL. Diagnosis of Clostridium difficile Infections in Children. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1425–1433. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03014-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dial S, Delaney JA, Barkun AN, Suissa S. Use of gastric acid-suppressive agents and the risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease. JAMA. 2005;294:2989–2995. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta A, Khanna S. Community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: an increasing public health threat. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:63–72. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S46780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer MP, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of community-onset Clostridium difficile infection in The Netherlands. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:1087–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang H, Weintraub A, Fang H, Nord CE. Community acquired Clostridium difficile infection due to a moxifloxacin susceptible ribotype 027 strain. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41:158–159. doi: 10.1080/00365540802484836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H, Fang H, Weintraub A, Nord CE. Distinct ribotypes and rates of antimicrobial drug resistance in Clostridium difficile from Shanghai and Stockholm. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:1170–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian TT, et al. Molecular Characterization of Clostridium difficile Isolates from Human Subjects and the Environment. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan Q, et al. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis of 104 Clostridium difficile strains isolated from China. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:195–199. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong D, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance mechanisms of clinical Clostridium difficile from a Chinese tertiary hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong D, et al. Clinical and microbiological characterization of Clostridium difficile infection in a tertiary care hospital in Shanghai, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:1601–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight DR, Elliott B, Chang BJ, Perkins TT, Riley TV. Diversity and Evolution in the Genome of Clostridium difficile. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:721–741. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00127-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elliott B, Dingle KE, Didelot X, Crook DW, Riley TV. The complexity and diversity of the Pathogenicity Locus in Clostridium difficile clade 5. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:3159–3170. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dingle KE, et al. Evolutionary history of the Clostridium difficile pathogenicity locus. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:36–52. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drudy D, Harnedy N, Fanning S, Hannan M, Kyne L. Emergence and control of fluoroquinolone-resistant, toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:932–940. doi: 10.1086/519181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuijper EJ, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea due to a clindamycin-resistant enterotoxin A-negative strain. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:528–534. doi: 10.1007/s100960100550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alfa MJ, et al. Characterization of a toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strain of Clostridium difficile responsible for a nosocomial outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2706–2714. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2706-2714.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goorhuis A, et al. Application of multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis to determine clonal spread of toxin A-negative Clostridium difficile in a general hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:1080–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins DA, Hawkey PM, Riley TV. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in Asia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2013;2:21. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eyre DW, et al. Diverse sources of C. difficile infection identified on whole-genome sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1195–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1216064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crews JD, et al. Risk Factors for Community-associated Clostridium difficile-associated Diarrhea in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:919–923. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jamal WY, Rotimi VO. Surveillance of Antibiotic Resistance among Hospital- and Community-Acquired Toxigenic Clostridium difficile Isolates over 5-Year Period in Kuwait. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kato N, et al. Identification of toxigenic Clostridium difficile by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:33–37. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.33-37.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knight DR, Thean S, Putsathit P, Fenwick S, Riley TV. Cross-sectional study reveals high prevalence of Clostridium difficile non-PCR ribotype 078 strains in Australian veal calves at slaughter. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:2630–2635. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03951-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stubbs SL, Brazier JS, O'Neill GL, Duerden BI. PCR targeted to the 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic spacer region of Clostridium difficile and construction of a library consisting of 116 different PCR ribotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:461–463. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.461-463.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffiths D, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:770–778. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01796-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).