Abstract

Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome (RSTS) is a multiple congenital anomalies syndrome associated with mutations in CREBBP (70%) and EP300 (5–10%). Previous reports have suggested an increased incidence of specific benign and possibly also malignant tumors. We identified all known individuals diagnosed with RSTS in the Netherlands until 2015 (n = 87) and studied the incidence and character of neoplastic tumors in relation to their CREBBP/EP300 alterations. The population–based Dutch RSTS data are compared to similar data of the Dutch general population and to an overview of case reports and series of all RSTS individuals with tumors reported in the literature to date. Using the Nationwide Network and Registry of Histopathology and Cytopathology in the Netherlands (PALGA Foundation), 35 benign and malignant tumors were observed in 26/87 individuals. Meningiomas and pilomatricomas were the most frequent benign tumors and their incidence was significantly elevated in comparison to the general Dutch population. Five malignant tumors were observed in four persons with RSTS (medulloblastoma; diffuse large‐cell B‐cell lymphoma; breast cancer; non‐small cell lung carcinoma; colon carcinoma). No clear genotype–phenotype correlation became evident. The Dutch population‐based data and reported case studies underscore the increased incidence of meningiomas and pilomatricomas in individuals with RSTS. There is no supporting evidence for an increased risk for malignant tumors in individuals with RSTS, however, due to the small numbers this risk may not be fully dismissed.

Keywords: CREBBP, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma, EP300, meningioma, neoplasia, Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome

1. INTRODUCTION

Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome (RSTS) is a congenital disorder characterized by intellectual disability, unusual behavior, postnatal growth retardation, and multiple congenital anomalies, especially of the face and distal limbs (Rubinstein & Taybi, 1963). The birth prevalence of RSTS is 1:100,000 to 1:125,000 (Hennekam, 2006). RSTS is caused by a heterozygous mutation in the gene encoding the transcriptional co‐activator CREB‐binding protein (CREBBP) on chromosome 16p13.3 in about 60% of affected individuals (Petrij et al., 1995), a submicroscopic deletion at 16p13.3 in about 10% of individuals (Hennekam, 2006), or a mutation of the gene E1A binding protein p300 (EP300) on chromosome 22q13.2 in about 5–10% of individuals (Fergelot et al., 2016; Roelfsema et al., 2005). In the remaining RSTS individuals, no specific genetic alterations can be detected and the diagnosis is based on the combination of clinical manifestations only. Most mutations occur de novo although vertical transmission of mutations has been described (Hennekam, 2006).

CREBBP and EP300 are closely related proteins belonging to the K‐acetyltransferase‐3 (KAT3) family of histone/protein lysine acetyltransferases, which serve as transcriptional co‐activators for a large number of DNA‐binding transcription factors that mediate multiple signaling and developmental pathways (Wang et al., 2010). Mutations in CREBBP and EP300 have been demonstrated in various benign and malignant tumors, including in up to 40% of diffuse large cell B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma cases (Lohr et al., 2012; Morin et al., 2011; Pasqualucci et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). A specific type of acute myeloid leukemia is associated with a chromosomal translocation involving CREBBP (Rozman et al., 2004).

Various benign and malignant tumors have been described in RSTS individuals. In 1989, Siraganian, Rubinstein, and Miller (1989) reported a series of 574 RSTS individuals in whom 22 tumors were detected in 19 persons (3.3%). Nine were malignant, 13 were benign, and 79% occurred under the age of 20. Miller and Rubinstein (1995) expanded the above series and reported 36 tumors in 725 RSTS individuals (5%). Tumors of the central nervous system and of hematological origin were relatively frequently reported (12 and 6 of 36 neoplasms, respectively) and two individuals with pilomatricomas were noted. For both studies, molecular confirmation of RSTS was not yet possible at the time of publication, preventing genotype–phenotype studies. Genotype–phenotype studies have not been performed in subsequent reports either. The data in these series were composed of cases reported in literature and cases reported to Dr Jack Rubinstein (Miller & Rubinstein, 1995; Siraganian et al., 1989).

Individuals with RSTS are prone to develop excessive scar tissue (keloids). In 24% of RSTS individuals, itching keloids develop during puberty and adulthood (van de Kar et al., 2014). It has been suggested that, similarly to other neoplastic processes, keloids in RSTS individuals may also be a result of deregulated proliferation of fibroblasts and thereby may serve as a model to study in those individuals the earliest oncogenic changes (Siraganian et al., 1989; van de Kar et al., 2014).

Here, we report the results of a study on the incidence of benign and malignant tumors and on possible genotype–phenotype correlations in a nation‐wide, population‐based study covering all known RSTS individuals in the Netherlands between 1986 and 2015. The results are compared to an overview of all reported tumors in individuals with RSTS in the literature to date.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study population

In the Netherlands, individuals diagnosed with RSTS are identified with an almost complete coverage, as most families with a child with RSTS become member of the dedicated support group (Stichting RSTS) and until 2010 all molecular diagnostics for RSTS have been performed in a single laboratory (Leiden University Medical Centre). Furthermore, affected individuals and their families are almost invariably seen in the expertise clinic for individuals with RSTS led one of the authors (RCH). All families known to either of these sources were contacted and informed consent was obtained for all individuals with RSTS in the present study. The characteristics of all participants, including results of physical exams and presence of keloids, had been obtained during various, typically repeated exams of all individuals by one of the authors (RCH). The study, including linkage of name, sex, and date of birth via a “Trusted Third Partner” to PALGA, has been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam (NL33011.018.11).

2.2. PALGA database search for benign and malignant tumors in individuals with RSTS

Since 1985, all pathology reports are centrally archived in the nationwide network and registry of histopathology and cytopathology in the Netherlands (PALGA), with a nationwide coverage of all academic and non‐academic hospitals since 1990 (Casparie et al., 2007). Standardized coding allows for comprehensive searches for specific and detailed diagnoses and patient cohorts, while still compliant to current privacy regulations.

Using the name, sex, and date of birth, all histopathological and cytological pathology registrations of all known RSTS individuals were retrieved from the PALGA database. To identify relevant diagnoses that may not be diagnosed by histopathological or cytological examination, and therefore may not be registered in PALGA (e.g., acute leukemia), the database of the Netherlands Cancer Registry was searched using the same strategy. Medical data, including results of physical exams and presence of keloids, were retrieved from the files of one of the authors (RCH). Benign and malignant tumors were defined as described by Willis (1952).

All relevant pathology slides were retrieved from the original pathology laboratories and reviewed by two experienced pathologists (PW, DDJ). Presence of keloid lesions was assessed predominantly on clinical grounds, as described elsewhere (van de Kar et al., 2014) and histologically confirmed if reported in the PALGA database.

All available genotype data for both CREBBP and EP300 mutations were obtained from the original diagnostic laboratories. All molecular studies had been performed as part of routine clinical work‐up, no additional molecular studies were performed specifically for the present study. Only individuals with a proven variant in CREBBP or EP300 were included in analysis.

2.3. Literature review of benign and malignant tumors in individuals with RSTS

A PubMed search was performed using the queries “Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome,” “Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome,” “Rubinstein–Taybi,” and “Rubinstein–Taybi” as to cover all publications on RSTS. All retrieved publications, including individual case reports and case series, were scanned for tumors. The references in the publications were hand‐searched for further publications. Publications in other languages than English were excluded. There were no other exclusion criteria.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Benign and malignant tumors in individuals with RSTS in the Netherlands

Between 1986 and 2015, 87 persons (37 male, 50 female), have been clinically diagnosed with RSTS in the Netherlands. Characteristics of the affected individuals with known mutation data are listed in Table 1; further details of all RSTS individuals are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Overview of tumors detected between 1986 and 2015 in individuals with molecularly confirmed RSTS in the Netherlands

| Age at time of present study | Sex | Neoplasm | Age at histopathological diagnosis | Keloid | Affected gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsense and frameshift mutation | |||||

| 6 | M | − | CREBBP | ||

| 8 | F | Pilomatricoma | 4 | + | CREBBP |

| 8 | F | − | CREBBP | ||

| 8 | F | − | CREBBP | ||

| 10 | M | − | EP300 | ||

| 12 | F | + | CREBBP | ||

| 15 | M | n/a | CREBBP | ||

| 21 | M | Hemangioma | 15 | − | CREBBP |

| 23 | M | + | CREBBP | ||

| 27 | F | n/a | CREBBP | ||

| 31 | M | + | CREBBP | ||

| 40 | F | + | CREBBP | ||

| 46† | M | + | CREBBP | ||

| 56 | M | n/a | CREBBP | ||

| 57† | M | DLBCL | 57 | − | CREBBP |

| 59† | F | + | CREBBP | ||

| 59 | M | − | CREBBP | ||

| 65† | F | Meningioma Hemangioma | 41 42 | − | CREBBP |

| Deletions and duplications | |||||

| 2 | M | n/a | CREBBP | ||

| 15 | M | − | CREBBP | ||

| 16 | F | Pilomatricoma | 5 | − | CREBBP |

| 16 | F | − | CREBBP | ||

| 19 | M | − | CREBBP | ||

| 22 | M | Pilomatricoma | 2 | − | CREBBP |

| 24 | F | Pilomatricoma | 9 | + | CREBBP |

| 30 | M | Pilomatricoma | 14 | + | CREBBP |

| 30 | M | Nevus Nevus | 9 25 | n/a | CREBBP |

| 30 | F | − | CREBBP | ||

| 34 | F | Pilomatricoma Pilomatricoma | 6 15 | + | CREBBP |

| 34† | F | Meningioma Breast carcinoma NSCLC | 29 31 34 | − | CREBBP |

| 40 | F | Pilomatricoma Pilomatricoma | 19 37 | − | EP300 |

| 41 | F | n/a | CREBBP | ||

| 42† | F | Neuroma Dermatofibroma Meningioma Meningioma | 29 32 36 37 | − | CREBBP |

| 43† | M | − | CREBBP | ||

| 53 | F | Fibroadenoma of breast Meningioma | 38 46 | n/a | CREBBP |

| Splice site mutation | |||||

| 10† | M | Medulloblastoma | 9 | − | CREBBP |

| 39 | M | Pilomatricoma | 15 | − | CREBBP |

| 40 | M | − | CREBBP | ||

| 52 | F | n/a | CREBBP | ||

| 59† | M | Colon carcinoma | 58 | + | CREBBP |

| Missense mutation | |||||

| 23 | F | − | EP300 | ||

| 46 | F | HSIL | 49 | + | CREBBP |

| Mutation type unknown | |||||

| 2 | F | − | EP300 | ||

| 21 | F | n/a | CREBBP | ||

| 30 | F | − | EP300 | ||

†, Deceased; N/A, data not available; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung carcinoma; DLBCL, Diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma; HSIL, high grade squamous intra‐epithelial lesion of the cervix.

All RSTS diagnoses were confirmed based on clinical criteria by a single observer (RCH). Cytogenetic and/or molecular confirmation for CREBBP and EP300 has been performed only after this had become available in 1993 and 1995, respectively, and if indicated for patient care reasons and genetic counseling of family members. The median age at the time of our study was 31 years (range 2–69 years). At the time of the study 15 individuals were deceased, at a median age of 47.7 years (range 10.4–69.7 years).

For 51/87 clinically diagnosed RSTS individuals, histological and/or cytological assessments were recorded in the PALGA database. In total, 159 histological and cytological reports were retrieved in which 35 neoplastic tumor diagnoses were identified in 26 individuals with a maximum of four per person. All diagnoses were confirmed by review of the relevant pathology slides. Five malignant tumors were found in four persons (medulloblastoma, diffuse large cell B‐cell lymphoma, non‐small cell lung carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and colon carcinoma), and two individuals had a premalignant proliferation (both high‐grade squamous intraepithelial lesion of the cervix). Five meningiomas were found in four persons and 23 other, benign tumors were found in 18 individuals, almost exclusively benign cutaneous tumors. Tumors in molecularly confirmed RSTS individuals are listed in Table 1, tumors in all RSTS individuals are provided in Supplementary Table S1

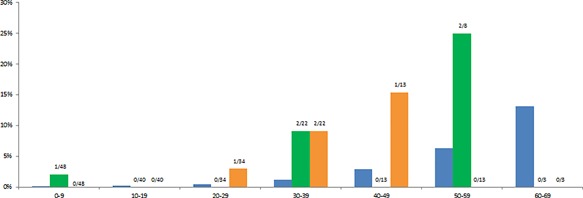

Though the percentage of individuals with a malignant tumor was higher in specific age categories (Figure 1), numbers were too small to make a reliable comparison.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of malignant tumors and meningiomas in Dutch individuals with molecularly confirmed RSTS compared to that of the general Dutch population per age cohort. Blue, malignant tumors in the general Dutch population; green, malignant tumors in the Dutch RSTS population; orange, meningiomas in the Dutch RSTS population (Cumulative meningioma incidence is <0,1% in general Dutch population). Data on general population from www.cijfersoverkanker.nl (retrieved June, 2017). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.2. Review of the literature

A PubMed search yielded 650 publications since the original report in 1963 (Rubinstein & Taybi, 1963). Fifty‐two papers contained data on additional individuals with RSTS with tumors and together these described 97 benign and malignant tumors in 89 individuals. This means that, including the present study, a total of 132 tumors have been reported in 115 individuals with RSTS. An overview of all reported tumors in RSTS is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Literature overview of tumors reported in individuals with RSTS (including present study)

| Neoplasm | Age | Sex | Affected gene | Mutation | Keloid | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological | ||||||

| Medulloblastoma | 4 | M | None found | n/a | + | Bartsch et al. (2005) |

| Medulloblastoma | 8 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Bourdeaut et al. (2014) |

| Medulloblastoma | 9 | M | CREBBP | c.1941+3A>T | − | Present study |

| Medulloblastoma | 8 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Evans, Burnell, Campbell, Gattamaneni, and Birch (1993); Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Medulloblastoma | 9 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Skousen et al. (1996) |

| Medulloblastoma | 9 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Neuroblastoma | 0 | M | CREBBP | c.605dupC | n/a | de Kort, Conneman, and Diderich (2014) |

| Neuroblastoma | 0 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Neuroblastoma | 3 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Neuroblastoma | 7 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Ihara, Kuromaru, Takemoto, and Hara (1999) |

| Glioma | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Lannering, Marky, and Nordborg (1990) |

| Glioma | 2 | F | CREBBP | c.4134G>T | n/a | Bartsch et al. (2010) |

| Glioma | n/a | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Lannering et al. (1990) |

| Oligodendroglioma | 2 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Neurilemmoma | 13 | M | n/a | n/a | + | Russell, Hoffman, and Bain (1971); Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Neuroma | 3 | F | CREBBP | c.5838_5857dup | n/a | Tornese et al. (2015) |

| Neuromaf | 29 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion 9‐31 | − | Present study |

| Pheochromocytoma | 10 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Bonioli and Bellini (1992); Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Adrenocortical adenoma | 22 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Pinealoma | 14 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Pituitary adenoma | 49 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Meningioma | ||||||

| Meningiomac | 29 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion | − | Present study |

| Meningiomaf | 36 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion 9‐31 | − | Present study |

| Meningiomaf | 37 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion 9‐31 | − | Present study |

| Meningioma | 39 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Bilir, Bilir, and Wilson (1990) |

| Meningioma | 39 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Meningiomab | 41 | F | CREBBP | c.1011dupA | − | Present study |

| Meningiomae | 46 | F | CREBBP | Exonic duplication 4‐23 | n/a | Present study |

| Hematological | ||||||

| Leukemia (ALL) | 0 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Shaheed, Khamaiseh, Rifai, and Abomelha (1999) |

| Leukemia (ALL) | 2 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Leukemia (ALL) | 3 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Leukemia (ALL) | 6 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Leukemia (AML) | 16 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Jonas, Heilbron, and Ablin (1978); Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Lymphoma (follicular) | 28 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion | n/a | Mar, Digiuseppe, and Dailey (2016) |

| Lymphoma (mediastinal) | 34 | F | CREBBP | c.2842C>T | + | Wieczorek et al. (2009) |

| Lymphoma (DLBCL) | 57 | M | CREBBP | c.4837delG | − | Present study |

| Lymphoma (non‐Hodgkin's)l | 33 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Lymphoma (non‐Hodgkin's) | 24 | M | n/a | n/a | + | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Lymphoma (non‐Hodgkin's)j | 58 | F | None found | n/a | n/a | Bartsch et al. (2005) |

| Genital | ||||||

| Embryonal carcinoma | 1 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Ovarian carcinoma (serous)h | 29 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Johannesen, Williams, Miller, and Tuller (2015) |

| Endometrium adenocarcinomah | 29 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Johannesen et al. (2015) |

| MGSCST | 14 | M | No deletion | n/a | n/a | Kurosawa, Fukutani, Masuno, Kawame, and Ochiai (2002) |

| Seminoma testis | 27 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Germ cell tumor testis | 0 | M | CREBBP | c.1824‐1G>A | n/a | Butler et al. (2016) |

| HSIL | 31 | F | n/a | n/a | − | Present study |

| HSIL | 49 | F | CREBBP | c.4340C>T | + | Present study |

| Cystadenoma (paratubal) | 15 | F | n/a | n/a | + | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Leiomyoma uterus | 22 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Present study |

| Leiomyomaa | 48 | F | n/a | n/a | − | Present study |

| Dermoid cyst | 5 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Bozkirli et al. (2000) |

| Teratoma ovaryl | 22 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Soft tissue | ||||||

| Leiomyosarcoma | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Stevens, Pouncey, and Knowles (2011) |

| Leiomyosarcoma omentum | 11 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Rhabdomyosarcomak | 4 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989); Sobel and Woerner (1981) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 5 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995); Ruymann et al. (1988) |

| Hemangioendothelioma | 1 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Altintas and Cakmakkaya, (2004) |

| Granular cell tumor | 22 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Burton, Kumar, and Bradford (1997) |

| Giant cell tumor | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Stevens et al. (2011) |

| Circumscribed storiform collagenoma | 8 | M | n/a | n/a | + | Zavras, Mennonna, Maris, and Vaos (2016) |

| Fibrolipomaa | 46 | F | n/a | n/a | − | Present study |

| Leiomyoma duodenumk | n/a | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989); Sobel and Woerner (1981) |

| Other malignant tumors | ||||||

| Colon cancerj | 50 | F | None found | n/a | n/a | Bartsch et al. (2005) |

| Colon carcinoma | 58 | M | CREBBP | c.4561‐2A>G | + | Present study |

| Thyroid cancer | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Stevens et al. (2011) |

| Thyroid cancerj | 54 | F | None found | n/a | n/a | Bartsch et al. (2005) |

| Lung carcinoma (NSCLC)c | 34 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion | − | Present study |

| Hepatoblastoma | 0 | F | CREBBP | c.4650_4654del | n/a | Milani et al. (2016) |

| Renal tumor | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Stevens et al. (2011) |

| Odontoma | 7 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Felgenhauer (1973); Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Parathyroid adenoma | 18 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Thymoma | 11 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Verhoeven, Tuinier, Kuijpers, Egger, and Brunner (2010) |

| Breast | ||||||

| Breast adenocarcinomac | 31 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion | − | Present study |

| Breast cancer | 55 | F | EP300 | c.4066C>T | − | Fergelot et al. (2016) |

| Breast cancerj | 43 | F | None found | n/a | n/a | Bartsch et al. (2005) |

| Breast cancer | n/a | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Levitas and Reid (1998) |

| Fibroadenoma breaste | 38 | F | CREBBP | Exonic duplication 4‐23 | n/a | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma | ||||||

| Pilomatricoma | 2 | M | CREBBP | Microdeletion | − | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma | 4 | F | CREBBP | c.1318C>T | + | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma | 4 | F | No deletion | n/a | − | Masuno et al. (1998) |

| Pilomatricoma (multiple) | 4–20 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Bayle et al. (2004) |

| Pilomatricoma | 5 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion 1‐4 | − | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma | 5 | M | No deletion | n/a | − | Masuno et al. (1998) |

| Pilomatricomag | 6 | F | CREBBP | c.2199delG | n/a | Yoo et al. (2015) |

| Pilomatricoma (multiple) | 6,15 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion 1‐31 | + | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma | 8 | F | EP300 | c.1948delA | n/a | Sellars, Sullivan, and Schaefer (2016) |

| Pilomatricoma | 9 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion 1‐31 | + | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma | 10 | F | No deletion | n/a | + | Masuno et al. (1998) |

| Pilomatricoma (multiple) | 12 | F | CREBBP | c.5837dupC | n/a | Rokunohe, Nakano, Akasaka, Toyomaki, and Sawamura (2016) |

| Pilomatricoma (multiple) | 12 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Cambiaghi, Ermacora, Brusasco, Canzi, & Caputo (1994); Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Pilomatricoma | 12 | F | CREBBP | t(2;16)(p13.3;p13.3) | − | Imaizumi and Kuroki (1991); Masuno et al. (1998) |

| Pilomatricoma | 12 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Miller and Rubinstein (1995) |

| Pilomatricoma | 14 | M | CREBBP | Exonic duplication 12‐19 | + | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma | 15 | M | CREBBP | c.4394 +–4A>C | − | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma (multiple) | 19,37 | F | EP300 | Microdeletion 24‐29 | − | Present study |

| Pilomatricoma | 49 | F | CREBBP | c.6127C>T | + | Papathemeli et al. (2015) |

| Pilomatricoma | n/a | F | EP300 | c.5153C>T | − | Negri et al. (2015) |

| Pilomatricoma | n/a | F | EP300 | Microdeletion | − | Negri et al. (2015) |

| Pilomatricoma (multiple) | n/a | F | CREBBP | c.4627G>T | − | Lopez‐Atalaya et al. (2012) |

| Pilomatricoma | n/a | F | EP300 | c.1553_1554dup | − | Fergelot et al. (2016) |

| Pilomatricoma | n/a | F | EP300 | c.4946G>A | + | Fergelot et al. (2016) |

| Pilomatricoma | n/a | F | EP300 | c.2113C>T | + | Fergelot et al. (2016) |

| Pilomatricoma | n/a | M | EP300 | c.4954_4957dup | − | Fergelot et al. (2016) |

| Pilomatricoma | n/a | F | EP300 | c.1876C>T | + | Fergelot et al. (2016) |

| Pilomatricoma (multiple patients) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Stevens et al. (2011) |

| Pilomatricoma | n/a | F | CREBBP | 6122_6125del | n/a | Chiang et al. (2009) |

| Vascular | ||||||

| Angiofibroma | 5 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Angioma (cerebellum) | n/a | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Thienpont et al. (2010) |

| Soft tissue angioma | n/a | M | EP300 | Microdeletion 1‐31 | n/a | Negri et al. (2015) |

| Hamartoma (occipital) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Stevens et al. (2011) |

| Hemangioma | 15 | M | CREBBP | c.406C>T | − | Present study |

| Hemangioma (capillary) | 1 | M | CREBBP | del(16)(p13.3p13.3) | n/a | Bartsch et al. (1999) |

| Hemangioma (capillary)i | n/a | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Sahiner, Senel, Erkek, Karacan, and Yoney (2009) |

| Hemangioma (capillary) | n/a | M | No deletion | n/a | + | Balci et al. (2004) |

| Hemangioma (forehead) | 0 | M | CREBBP | c.778C>T | n/a | Wincent et al. (2016) |

| Hemangioma (forehead) | n/a | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion | − | Lopez‐Atalaya et al. (2012) |

| Hemangioma (frontal) | 0 | F | n/a | n/a | − | Candan, Ornek, and Candan (2014) |

| Hemangioma (glabella) | n/a | M | CREBBP | Microdeletion | n/a | Rusconi et al. (2015) |

| Hemangioma (glabella) | n/a | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion 4‐16 | n/a | Rusconi et al. (2015) |

| Hemangioma (hepatic)i | 6 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Sahiner et al. (2009) |

| Hemangioma (uvula)b | 41 | F | CREBBP | c.1011dupA | − | Present study |

| Other benign skin tumors | ||||||

| Dermatofibromaf | 32 | F | CREBBP | Microdeletion 9‐31 | − | Present study |

| Dermoid cyst eye | 6 | F | n/a | n/a | + | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Glomus tumorm | n/a | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Siraganian et al. (1989) |

| Lacrimal caruncle nevus | 28 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Pogrzebielski, Piwowarczyk, Kohylarz, and Romanowska‐Dixon (2007) |

| Naevus depigmentosusg | 6 | F | CREBBP | c.2199delG | n/a | Yoo et al. (2015) |

| Nevus | 8 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | Schepis, Greco, Siragusa, Batolo, and Romano (2001) |

| Nevusd | 9 | M | CREBBP | Exonic duplication 4‐23 | n/a | Present study |

| Nevus | 21 | F | n/a | n/a | − | Present study |

| Nevusd | 25 | M | CREBBP | Exonic duplication 4‐23 | n/a | Present study |

| Nevus | 40 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | Present study |

| Spitznevus | 20 | F | n/a | n/a | − | Present study |

“a” to “m,” Same individual having more than one tumor; Age, age at onset; n/a, data not available; M, male; F, female; ALL, acute lymphatic leukemia; AML, acute myeloblastic leukemia; MGSCST, malignant gonadal sex cord stromal tumor; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung carcinoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma; HSIL, high‐grade squamous intra‐epithelial lesion of the cervix.

3.3. Genotype–phenotype correlation

In 51 of the 87 RSTS individuals in the present cohort, information on the germline variant in CREBBP (n = 42) or EP300 (n = 3) was available. Variants could be classified as missense mutations leading to single amino acid alterations (n = 4), large deletions and duplications (n = 18), nonsense and frameshift mutations resulting in early truncation (n = 18), and splice site mutations (n = 5). In three patients, a germline variant in CREBBP (n = 1) and EP300 (n = 2) was reported without further details and in eight patients no germline variant in either gene was found, despite a clinical diagnosis of RSTS.

Benign and malignant tumors were predominantly found in the large deletion/duplication group (19 tumors in 10/18 patients) and to a lesser extent in the groups with nonsense/frameshift mutations, (5 tumors in 4/14 patients), splice site mutations (3 tumors in 3/5 patients), and missense mutations groups (1 tumor in 4 patients). However, the effect of different variants on protein function is fully unpredictable, precluding any conclusions on specific associations and thus no clear genotype–phenotype correlations were observed in our series.

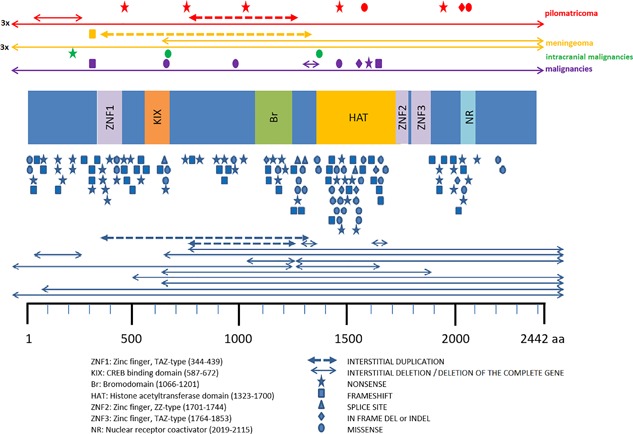

In the eight individuals without a detectable germline variant in CREBBP or EP300, no tumors were observed. There was no clear clustering of pathogenic variants in relation to tumors within the functional domains of CREBBP, and the variants are spread along the gene in the groups with and without tumors in similar ways (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Variants in CREBBP in present cohort of individuals with RSTS with pilomatricoma, meningioma, intracranial malignancies, and other malignancies, compared to all CREBBP variants reported in LOVD. Various functional protein domains are indicated schematically. Individuals with a tumor from the present series of individuals with RSTS are indicated above the protein cartoon, individuals with RSTS reported in the LOVD are reported below the cartoon, each line or symbol representing a single individual. No specific distinction can be made between those with and without tumors in the latter series as this information is not known for all individuals. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The CREBBP/EP300 mutation status was available in 28 RSTS individuals with a tumor reported in the literature, 10 missense mutations, 9 with truncating mutations, 7 with large deletions, 1 with a splice site mutation, and 1 with a translocation.

4. DISCUSSION

In this nation‐wide, population‐based cohort of 87 Dutch individuals with RSTS, the incidence of benign and malignant tumors was assessed. In Dutch individuals with RSTS, various malignant tumors were observed. Per age category, the incidence is compared to the general Dutch population (IKNL, [Link]), but small numbers preclude formal epidemiological risk assessment (Figure 1). The overall frequency of malignancies in the presently reported Dutch RSTS population (8.3% in those with proven variants, 4.6% overall) is higher than previously reported by Siraganian and Miller (1.5% and 2.3%, respectively) (Miller & Rubinstein, 1995; Siraganian et al., 1989) in individuals with an age distribution similar to the present cohort. As the same definition for malignant tumors was used by the latter authors as by us, this may be caused by the opportunity in the Netherlands of using a comprehensive, population‐based, and nation‐wide search strategy. However, as PALGA has a nation‐wide coverage since 1989 only, the number of tumors may still be an underestimation, as tumors that have occurred before 1989 may have been missed.

In the present cohort, no single type of malignancy predominated. One individual with medulloblastoma and one individual with DLBCL were observed at (expected) ages of 9 and 57 years, respectively. In literature, five cases of medulloblastoma and 11 hematological malignancies have been reported at ages of 4–9 years and 0–58 years, respectively. The selection bias in the overview due to using case reports and non‐systematically gathered case‐series, prevents drawing any conclusions with respect to true frequencies of these tumors in individuals with RSTS or to associations between tumors and CREBBP/EP300 variants.

Meningiomas were present in 8.3% of molecularly proven Dutch RSTS individuals (4.6% of all Dutch RSTS individuals) and occur in <0.1% in the general Dutch population (Casparie et al., 2007; Wiemels, Wrensch, & Claus, 2010), supporting an increased risk to develop meningioma in RSTS individuals (Bourdeaut et al., 2014; Miller & Rubinstein, 1995; Skousen, Wardinsky, & Chenaille, 1996). This is further supported by presentation of two metachronous, independent meningiomas in a single individual in the present study, who has been reported before separately (Verstegen, van den Munckhof, Troost, & Bouma, 2005).

Pilomatricomas were found frequently (16.7% of molecularly proven and 9.2% of all individuals in the present study group; 0.16% histopathological diagnoses in general population in the same time interval (Casparie et al., 2007). Likely the incidence of pilomatricomas is even higher, since these are usually diagnosed on clinical grounds and only excised and submitted for histopathological examination when giving complaints. The same applies for naevi and other benign skin lesions. Though perhaps of little clinical importance, the association between RSTS and pilomatricoma remains intriguing, and may have a similar background as the increased frequency of keloids in individuals with RSTS (van de Kar et al., 2014). In the Dutch RSTS population, however, we have been unable to detect an association between their occurrences.

In the present cohort, genotype–phenotype correlation could be studied in 48 individuals for whom information regarding the CREBBP and EP300 mutation status was available, and in literature similar data were available for 28 persons with RSTS. There was no obvious correlation between the incidence of tumors in general or specific tumor types with the location of variants within CREBBP. Tumors may be somewhat more common in individuals carrying large deletions as such deletions occur in 10% of RSTS individuals only (van Belzen, Bartsch, Lacombe, Peters, & Hennekam, 2011), but no firm conclusion is possible without data on much larger groups of RSTS individuals. A specific surveillance in children or adults with RSTS to detect tumors at an earlier age is not indicated based on presently available data.

In our cohort, we observed one patient with DLBCL (germinal center B‐cell [GCB]‐like subtype). Since somatic CREBBP mutation is a very frequent early event in follicular B‐cell lymphoma and diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (Lohr et al., 2012; Morin et al., 2011; Pasqualucci et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011), this case was studied for somatic CREBBP alterations (Stevens et al., 2017). A somatic CREBBP mutation on one allele was found (His1438Asp, variant allele frequency [VAF] 25%), while the known germline mutation (CREBBP c.4837delG) was found in only 6% of sequence reads. These results should be interpreted as deletion of the germline mutated allele with an acquired, possibly subclonal alteration on the other allele in tumor cells. This may be suggestive of a tumor suppressor model for CREBBP in lymphoma.

Possible relations between somatic CREBBP/EP300 mutations in other tumors have been implied. A biallelic deletion of CREBBP in medulloblastoma has been demonstrated (Bourdeaut et al., 2014), and somatic mutations have been detected in small numbers of breast and colon carcinomas well (Iyer, Ozdag, & Caldas, 2004). Linking CREBBP/EP300 to meningiomas and pilomatricomas would be very interesting, however to our knowledge, no literature to date is available regarding these tumors. More comprehensive research is required to study the possible role of CREBBP and EP300 in oncogenesis.

Based on a nationwide, population‐based study, we conclude that RSTS individuals are at increased risk to develop meningiomas and pilomatricomas. An increased risk for malignant tumors could not be substantiated, but can also not be fully dismissed based on the small numbers of affected individuals both reported by us and in the literature and additional (international) studies are warranted. No genotype–phenotype correlation became evident. Based on the present data, a surveillance for specific tumors is not indicated in individuals with RSTS.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Table S1. Overview of All Individuals with Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome in the Netherlands and tumors detected between 1986 and 2015.

Boot MV, van Belzen MJ, Overbeek LI, et al. Benign and malignant tumors in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2018;176A: 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.38603

Raoul C. Hennekam and Daphne de Jong contributed equally.

REFERENCES

- Altintas, F. , & Cakmakkaya, S. (2004). Anesthetic management of a child with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Paediatric Anaesthesia, 14(7), 610–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balci, S. , Bostanci, S. , Ekmekci, P. , Cebeci, I. , Bokesoy, I. , Bartsch, O. , & Gurgey, E. (2004). A 15‐year‐old boy with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome associated with severe congenital malalignment of the toenails. Pediatric Dermatology, 21(1), 44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, O. , Kress, W. , Kempf, O. , Lechno, S. , Haaf, T. , & Zechner, U. (2010). Inheritance and variable expression in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A, 152A(9), 2254–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, O. , Schmidt, S. , Richter, M. , Morlot, S. , Seemanova, E. , Wiebe, G. , & Rasi, S. (2005). DNA sequencing of CREBBP demonstrates mutations in 56% of patients with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome (RSTS) and in another patient with incomplete RSTS. Journal of Human Genetics, 117(5), 485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, O. , Wagner, A. , Hinkel, G. K. , Krebs, P. , Stumm, M. , Schmalenberger, B. , … Majewski, F. (1999). FISH studies in 45 patients with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: Deletions associated with polysplenia, hypoplastic left heart and death in infancy. European Journal of Human Genetics, 7(7), 748–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayle, P. , Bazex, J. , Lamant, L. , Lauque, D. , Durieu, C. , & Albes, B. (2004). Multiple perforating and non perforating pilomatricomas in a patient with Churg–Strauss syndrome and Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 18(5), 607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilir, B. M. , Bilir, N. , & Wilson, G. N. (1990). Intracranial angioblastic meningioma and an aged appearance in a woman with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Supplement, 6, 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonioli, E. , & Bellini, C. (1992). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome and pheochromocytoma. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 44(3), 386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeaut, F. , Miquel, C. , Richer, W. , Grill, J. , Zerah, M. , Grison, C. , … Delattre, O. (2014). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome predisposing to non‐WNT, non‐SHH, group 3 medulloblastoma. Pediatric Blood Cancer, 61(2), 383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkirli, F. , Gunaydin, B. , Celebi, H. , & Akcali, D. T. (2000). Anesthetic management of a child with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome for cervical dermoid cyst excision. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 14(4), 214–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton, B. J. , Kumar, V. G. , & Bradford, R. (1997). Granular cell tumour of the spinal cord in a patient with Rubenstein–Taybi syndrome. British Journal of Neurosurgery, 11(3), 257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, G. H. , Boyle, M. , Lynch, S. A. , Ryan, S. , McDermott, M. , & Capra, M. (2016). One to watch: A germ cell tumor arising in an undescended testicle in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 38(6)), 191–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambiaghi, S. , Ermacora, E. , Brusasco, A. , Canzi, L. , & Caputo, R. (1994). Multiple pilomatricomas in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: A case report. Pediatric Dermatology, 11(1), 21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candan, S. , Ornek, C. , & Candan, F. (2014). Ocular anomalies in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: A further case report and review of the literature. Clinical Dysmorphology, 23(4), 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casparie, M. , Tiebosch, A. T. , Burger, G. , Blauwgeers, H. , van de Pol, A. , van Krieken, J. H. , & Meijer, G. A. (2007). Pathology databanking and biobanking in the Netherlands, a central role for PALGA, the nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive. Cellular Oncology, 29(1), 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, P. W. , Lee, N. C. , Chien, N. , Hwu, W. L. , Spector, E. , & Tsai, A. C. (2009). Somatic and germ‐line mosaicism in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A, 149A(7), 1463–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kort, E. , Conneman, N. , & Diderich, K. (2014). A case of Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome and congenital neuroblastoma. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A, 164A(5), 1332–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. , Burnell, L. , Campbell, R. , Gattamaneni, H. R. , & Birch, J. (1993). Congenital anomalies and genetic syndromes in 173 cases of medulloblastoma. Medical and Pediatric Oncology, 21(6), 433–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felgenhauer, W. R. (1973). Syndrome of Rubinstein–Taybi (author's transl). Human Genetik, 20(1), 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergelot, P. , Van Belzen, M. , Van Gils, J. , Afenjar, A. , Armour, C. M. , Arveiler, B. , … Hennekam, R. C. (2016). Phenotype and genotype in 52 patients with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome caused by EP300 mutations. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A, 170(12), 3069–3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam, R. C. (2006). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. European Journal of Human Genetics, 14(9), 981–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara, K. , Kuromaru, R. , Takemoto, M. , & Hara, T. (1999). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: A girl with a history of neuroblastoma and premature thelarche. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 83(5), 365–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IKNL (2017, june 6) Nederlandse Kankerregistratie, beheerd door IKNL ©. retrieved from http://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl/

- Imaizumi, K. , & Kuroki, Y. (1991). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome with de novo reciprocal translocation t(2;16)(p13.3;p13.3). American Journal of Medical Genetics, 38(4), 636–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, N. G. , Ozdag, H. , & Caldas, C. (2004). P300/CBP and cancer. Oncogene, 23(24), 4225–4231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesen, E. J. , Williams, T. , Miller, D. C. , & Tuller, E. (2015). Synchronous ovarian and endometrial carcinomas in a patient with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: A case report and literature review. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology, 34(2), 132–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, D. M. , Heilbron, D. C. , & Ablin, A. R. (1978). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome and acute leukemia. The Journal of Pediatrics, 92(5), 851–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa, K. , Fukutani, K. , Masuno, M. , Kawame, H. , & Ochiai, Y. (2002). Gonadal sex cord stromal tumor in a patient with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Pediatrics International, 44(3), 330–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannering, B. , Marky, I. , & Nordborg, C. (1990). Brain tumors in childhood and adolescence in west Sweden 1970–1984. Epidemiology and Survival Cancer, 66(3), 604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitas, A. S. , & Reid, C. S. (1998). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 42(Pt 4), 284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr, J. G. , Stojanov, P. , Lawrence, M. S. , Auclair, D. , Chapuy, B. , Sougnez, C. , … Golub, T. R. (2012). Discovery and prioritization of somatic mutations in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) by whole‐exome sequencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(10), 3879–3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez‐Atalaya, J. P. , Gervasini, C. , Mottadelli, F. , Spena, S. , Piccione, M. , Scarano, G. , … Larizza, L. (2012). Histone acetylation deficits in lymphoblastoid cell lines from patients with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics, 49(1), 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar, N. , Digiuseppe, J. A. , & Dailey, M. E. (2016). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome—a window into follicular lymphoma biology. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 57(12), 2908–2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuno, M. , Imaizumi, K. , Ishii, T. , Kuroki, Y. , Baba, N. , & Tanaka, Y. (1998). Pilomatrixomas in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 77(1), 81–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani, D. , Bonarrigo, F. A. , Menni, F. , Spaccini, L. , Gervasini, C. , & Esposito, S. (2016). Hepatoblastoma in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: A case report. Pediatric Blood Cancer, 63(3), 572–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R. W. , & Rubinstein, J. H. (1995). Tumors in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 56(1), 112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin, R. D. , Mendez‐Lago, M. , Mungall, A. J. , Goya, R. , Mungall, K. L. , Corbett, R. D. , … Marra, M. A. (2011). Frequent mutation of histone‐modifying genes in non‐hodgkin lymphoma. Nature, 476(7360), 298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri, G. , Milani, D. , Colapietro, P. , Forzano, F. , Della Monica, M. , Rusconi, D. , … Gervasini, C. (2015). Clinical and molecular characterization of Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome patients carrying distinct novel mutations of the EP300 gene. Clinical Genetics, 87(2), 148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papathemeli, D. , Schulzendorff, N. , Kohlhase, J. , Goppner, D. , Franke, I. , & Gollnick, H. (2015). Pilomatricomas in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, 13(3), 240–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci, L. , Dominguez‐Sola, D. , Chiarenza, A. , Fabbri, G. , Grunn, A. , Trifonov, V. , … Dalla‐Favera, R. (2011). Inactivating mutations of acetyltransferase genes in B‐cell lymphoma. Nature, 471(7337), 189–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrij, F. , Giles, R. H. , Dauwerse, H. G. , Saris, J. J. , Hennekam, R. C. , Masuno, M. , … Breuning, M. A. (1995). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome caused by mutations in the transcriptional co‐activator CBP. Nature, 376(6538), 348–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogrzebielski, A. , Piwowarczyk, A. , Kohylarz, J. , & Romanowska‐Dixon, B. (2007). Lacrimal caruncle nevus associated with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Klinika Oczna, 109(7‐9), 330–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema, J. H. , White, S. J. , Ariyurek, Y. , Bartholdi, D. , Niedrist, D. , Papadia, F. , … Peters, D. J. (2005). Genetic heterogeneity in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: Mutations in both the CBP and EP300 genes cause disease. American Journal of Human Genetics, 76(4), 572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokunohe, D. , Nakano, H. , Akasaka, E. , Toyomaki, Y. , & Sawamura, D. (2016). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome with multiple pilomatricomas: The first case diagnosed by CREBBP mutation analysis. The Journal of Dermatological Science, 83(3), 240–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozman, M. , Camos, M. , Colomer, D. , Villamor, N. , Esteve, J. , Costa, D. , … Campo, E. (2004). Type I MOZ/CBP (MYST3/CREBBP) is the most common chimeric transcript in acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;16)(p11;p13) translocation. Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer, 40(2), 140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, J. H. , & Taybi, H. (1963). Broad thumbs and toes and facial abnormalities. A possible mental retardation syndrome. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 105, 588–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi, D. , Negri, G. , Colapietro, P. , Picinelli, C. , Milani, D. , Spena, S. , … Gervasini, C. (2015). Characterization of 14 novel deletions underlying Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: An update of the CREBBP deletion repertoire. Journal of Human Genetics, 134(6), 613–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, N. A. , Hoffman, H. J. , & Bain, H. W. (1971). Intraspinal neurilemoma in association with the Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Pediatrics, 47(2), 444–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruymann, F. B. , Maddux, H. R. , Ragab, A. , Soule, E. H. , Palmer, N. , Beltangady, M. , … Newton, W. A. Jr. (1988). Congenital anomalies associated with rhabdomyosarcoma: An autopsy study of 115 cases. A report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Committee (representing the Children's Cancer Study Group, the Pediatric Oncology Group, the United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group, and the Pediatric Intergroup Statistical Center). Medical and Pediatric Oncology, 16(1), 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahiner, U. M. , Senel, S. , Erkek, N. , Karacan, C. , & Yoney, A. (2009). Rubinstein Taybi syndrome with hepatic hemangioma. Medical Principles and Practice, 18(2), 162–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis, C. , Greco, D. , Siragusa, M. , Batolo, D. , & Romano, C. (2001). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome with epidermal nevus: A case report. Pediatric Dermatology, 18(1), 34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, E. A. , Sullivan, B. R. , & Schaefer, G. B. (2016). Whole exome sequencing reveals EP300 mutation in mildly affected female: Expansion of the spectrum. Clinical Case Reports, 4(7), 696–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheed, M. M. , Khamaiseh, R. A. , Rifai, S. Z. , & Abomelha, A. M. (1999). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome and lymphoblastic leukemia. Saudi Medical Journal, 20(10), 800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siraganian, P. A. , Rubinstein, J. H. , & Miller, R. W. (1989). Keloids and neoplasms in the Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Medical and Pediatric Oncology, 17(6), 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skousen, G. J. , Wardinsky, T. , & Chenaille, P. (1996). Medulloblastoma in patient with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 66(3), 367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, R. A. , & Woerner, S. (1981). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome and nasopharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma. The Journal of Pediatrics, 99(6), 1000–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, C. A. , Pouncey, J. , & Knowles, D. (2011). Adults with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A, 155A(7), 1680–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, W. B. C. , Mendeville, M. , Redd, R. , Clear, A. J. , Bladergroen, R. , Calaminici, M. , … de Jong, D. (2017). Prognostic relevance of CD163 and CD8 combined with EZH2 and gain of chromosome 18 in follicular lymphoma: A study by the Lunenburg Lymphoma Biomarker Consortium. Haematologica, 102(8), 1413–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thienpont, B. , Bena, F. , Breckpot, J. , Philip, N. , Menten, B. , Van Esch, H. , … Devriendt, K. (2010). Duplications of the critical Rubinstein–Taybi deletion region on chromosome 16p13.3 cause a novel recognisable syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics, 47(3), 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornese, G. , Marzuillo, P. , Pellegrin, M. C. , Germani, C. , Faleschini, E. , Zennaro, F. , … Ventura, A. (2015). A case of Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome associated with growth hormone deficiency in childhood. Clinical Endocrinology (Oxford), 83(3), 437–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belzen, M. , Bartsch, O. , Lacombe, D. , Peters, D. J. , & Hennekam, R. C. (2011). Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome (CREBBP, EP300). European Journal of Human Genetics, 19(1), 118–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Kar, A. L. , Houge, G. , Shaw, A. C. , de Jong, D. , van Belzen, M. J. , Peters, D. J. , & Hennekam, R. C. (2014). Keloids in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome: A clinical study. British Journal of Dermatology, 171(3), 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, W. M. , Tuinier, S. , Kuijpers, H. J. , Egger, J. I. , & Brunner, H. G. (2010). Psychiatric profile in Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. A Review and Case Report Psychopathology, 43(1), 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstegen, M. J. , van den Munckhof, P. , Troost, D. , & Bouma, G. J. (2005). Multiple meningiomas in a patient with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Case Report. Journal of Neurosurgery, 102(1), 167–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Weaver, I. C. , Gauthier‐Fisher, A. , Wang, H. , He, L. , Yeomans, J. , … Miller, F. D. (2010). CBP histone acetyltransferase activity regulates embryonic neural differentiation in the normal and Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome brain. Developmental Cell, 18(1), 114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, D. , Bartsch, O. , Lechno, S. , Kohlhase, J. , Peters, D. J. , Dauwerse, H. , … Passarge, E. (2009). Two adults with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome with mild mental retardation, glaucoma, normal growth and skull circumference, and camptodactyly of third fingers. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A, 149A(12), 2849–2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemels, J. , Wrensch, M. , & Claus, E. B. (2010). Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. Journal of Neuro‐Oncology, 99(3), 307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis, R. A. (1952). Beware of eponyms. McGill Journal of Medicine, 21(3), 174–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wincent, J. , Luthman, A. , van Belzen, M. , van der Lans, C. , Albert, J. , Nordgren, A. , & Anderlid, B. M. (2016). CREBBP and EP300 mutational spectrum and clinical presentations in a cohort of Swedish patients with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine, 4(1), 39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, H. J. , Kim, K. , Kim, I. H. , Rho, S. H. , Park, J. E. , Lee, K. Y. , … Kim, N. (2015). Whole exome sequencing for a patient with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome reveals de novo variants besides an overt CREBBP mutation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(3), 5697–5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavras, N. , Mennonna, R. , Maris, S. , & Vaos, G. (2016). Circumscribed storiform collagenoma associated with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome in a young adolescent. Case Reports in Dermatology, 8(1), 59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. , Mullighan, C. G. , Harvey, R. C. , Wu, G. , Chen, X. , Edmonson, M. , … Hunger, S. P. (2011). Key pathways are frequently mutated in high‐risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood, 118(11), 3080–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Table S1. Overview of All Individuals with Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome in the Netherlands and tumors detected between 1986 and 2015.