Abstract

Despite reducing progression and promoting regression of coronary atherosclerosis, statin therapy does not fully address residual cardiovascular (CV) risk. High‐purity eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) added to a statin has been shown to reduce CV events and induce regression of coronary atherosclerosis in imaging studies; however, data are from Japanese populations without high triglyceride (TG) levels and baseline EPA serum levels greater than those in North American populations. Icosapent ethyl is a high‐purity prescription EPA ethyl ester approved at 4 g/d as an adjunct to diet to reduce TG levels in adults with TG levels >499 mg/dL. The objective of the randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled EVAPORATE study is to evaluate the effects of icosapent ethyl 4 g/d on atherosclerotic plaque in a North American population of statin‐treated patients with coronary atherosclerosis, TG levels of 200 to 499 mg/dL, and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of 40 to 115 mg/dL. The primary endpoint is change in low‐attenuation plaque volume measured by multidetector computed tomography angiography. Secondary endpoints include incident plaque rates; quantitative changes in different plaque types and morphology; changes in markers of inflammation, lipids, and lipoproteins; and the relationship between these changes and plaque burden and/or plaque vulnerability. Approximately 80 patients will be followed for 9 to 18 months. The clinical implications of icosapent ethyl 4 g/d treatment added to statin therapy on CV endpoints are being evaluated in the large CV outcomes study REDUCE‐IT. EVAPORATE will provide important imaging‐derived data that may add relevance to the clinically derived outcomes from REDUCE‐IT.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Atherosclerotic Plaque, Cardiovascular Imaging Techniques, Eicosapentaenoic Acid, Icosapent Ethyl

1. INTRODUCTION

Statin therapy is the cornerstone of cardiovascular (CV) risk management. Despite reducing the progression of coronary atherosclerosis and promoting its regression, statin therapy does not fully address residual CV risk.1 This underscores the need for additional intervention.

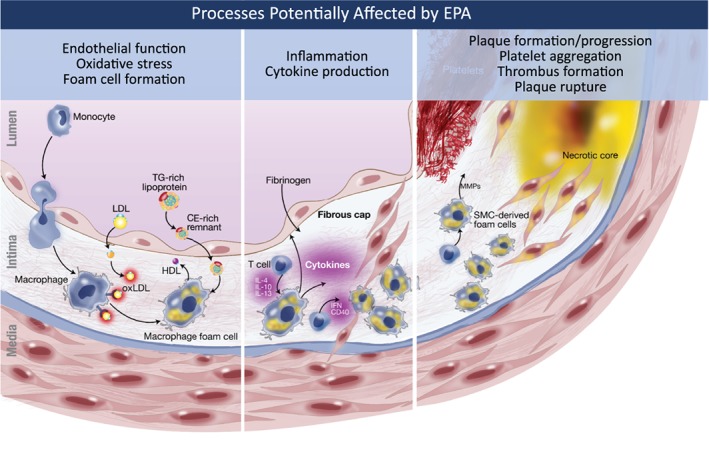

Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) is an omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acid that is incorporated into membrane phospholipids and atherosclerotic plaques. EPA exerts beneficial effects on the pathophysiologic cascade of plaque development, beginning from the onset of plaque formation through plaque rupture (Figure 1).2, 3 A number of specific salutary actions have been reported relating to endothelial function, oxidative stress, foam‐cell formation, inflammation, plaque formation/progression, platelet aggregation, thrombus formation, and plaque rupture (Figure 1).2 EPA‐enriched high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) particles, from patients with dyslipidemia treated with 1.8 g of EPA and in reconstituted HDL particles, have been shown to increase cholesterol efflux from macrophages and markedly inhibit cytokine‐induced expression of adhesion molecules in human umbilical‐vein endothelial cells.4, 5 EPA also improves atherogenic dyslipidemia by reducing triglyceride (TG) levels and remnant cholesterol without raising low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) levels in patients with very high TG levels6 and in statin‐treated patients with high TG levels and high residual CV risk.7 High‐purity EPA has been shown to induce beneficial effects on and regression of atherosclerotic plaque in preclinical studies utilizing animal models of atherosclerosis as well as in a range of clinical imaging studies, some of which included statin‐treated patients.8 In the Japan EPA Lipid Intervention Study (JELIS) of >18 000 statin‐treated Japanese patients with hypercholesterolemia, 1.8 g/d of high‐purity EPA significantly reduced the relative risk of major coronary events by 19% (P = 0.011) compared with placebo.9 Together, the multifaceted data from mechanistic, pathophysiologic, outcomes, and plaque‐imaging studies support the biologic plausibility of EPA as an antiatherosclerotic agent.2, 8 However, much of the outcomes and plaque‐imaging data are from Japanese populations without high TG levels, and in whom baseline EPA serum levels are greater than those of Western or North American populations.

Figure 1.

The potential effects of EPA on atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is a multistep process ranging from endothelial dysfunction to plaque development, progression, and rupture, leading to thrombus formation and cardiovascular events.2, 3 EPA has been reported to have beneficial effects on multiple atherosclerosis processes including endothelial function, oxidative stress, foam‐cell formation, inflammation/cytokines, plaque formation/progression, platelet aggregation, thrombus formation, and plaque rupture.2 Abbreviations: CE, cholesteryl ester; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; ox‐LDL, oxidized low‐density lipoprotein; SMC, smooth muscle cell; TG, triglycerides

Icosapent ethyl (Vascepa; Amarin Pharma Inc., Bedminster, NJ) is a high‐purity prescription EPA ethyl ester approved by the US Food and Drug Administration at a dose of 4 g/d as an adjunct to diet for the reduction of TG levels in adults with TG levels ≥500 mg/dL.10 Icosapent ethyl 4 g/d has been shown to increase serum EPA levels in a Western population to levels similar to those observed in the Japanese population from JELIS.11 Icosapent ethyl 4 g/d has also been shown to reduce the levels of TG and other atherogenic and inflammatory parameters without raising LDL‐C levels, as compared with placebo, in patients with very high TG levels and in statin‐treated patients with high TG levels and high CV risk.6, 7, 12, 13, 14 It is unknown whether adding icosapent ethyl to a statin will further reduce the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in Western/North American populations with residually high TG levels.

The objective of the Effect of Vascepa on Improving Coronary Atherosclerosis in People With High Triglycerides Taking Statin Therapy (EVAPORATE; NCT02926027) study is to evaluate the effects of icosapent ethyl 4 g/d on low‐attenuation plaque volume via multidetector computed tomography angiography (MDCTA) in a North American population of statin‐treated patients with elevated TG levels (200–499 mg/dL). We hypothesized that icosapent ethyl 4 g/d in combination with statin therapy would reduce the progression of low‐attenuation plaque volume over 9 to 18 months compared with the use of statin therapy alone.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

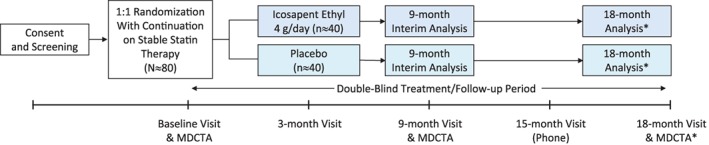

EVAPORATE is a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial being conducted at 2 centers in the United States. Eligible patients will be randomly assigned to icosapent ethyl 4 g/d or placebo (light liquid paraffin, matched for color, size, shape, weight, and odor) in a 1:1 fashion. Patients will be followed for ≥9 months or up to 18 months (if efficacy is not achieved at 9 months).

At baseline, patients will undergo a physical examination and an evaluation of blood pressure, height, weight, and laboratory blood testing. Cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA), using state‐of‐the‐art MDCTA technology, will be used to evaluate coronary plaque volume/composition (for additional details see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). The evaluations of plaque using CCTA will be repeated at month 9 and, if needed, at month 18. Adverse events will be monitored throughout the study. The trial schema is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

EVAPORATE study design. At baseline and 9 months, assessments will include BP, height, weight, laboratory blood testing, physical examinations, MDCTA (to assess progression of low‐attenuation plaque volume), and safety evaluation. Safety will also be assessed at 3 months for all patients and at 15 months for patients continuing for a total of 18 months of treatment. *If a statistician and the Data Safety and Monitoring Board find that efficacy is not achieved at 9 months, patients will be followed for an additional 9 months to assess progression of low‐attenuation plaque volume by MDCTA. If a P value of ≤0.006 is achieved at 9 months, then the study will terminate because the efficacy boundary will have been achieved. Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; EVAPORATE, Effect of Vascepa on Improving Coronary Atherosclerosis in People With High Triglycerides Taking Statin Therapy study; MDCTA, multi‐detector computed tomography angiography

2.2. Study population

Major study inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, eligible patients will be age 30 to 85 years with coronary atherosclerosis (narrowing of ≥20% in 1 coronary artery by either invasive angiography or MDCTA) and elevated fasting TG levels (200–499 mg/dL) and LDL‐C levels ≥40 and ≤115 mg/dL. Statin therapy (with or without ezetimibe) as well as diet and exercise must be stable for ≥4 weeks prior to study entry.

Table 1.

EVAPORATE key inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Age 30–85 y | Use of medications or dietary supplements that may alter plasma lipids |

| Elevated TG (200–499 mg/dL) | BMI >40 kg/m2 |

| LDL‐C ≥40 and ≤115 mg/dL on statin therapy | History of known MI, stroke, life‐threatening arrhythmia, or HF |

| Stable diet and exercise | Pregnancy |

| Stable treatment with a statin ± ezetimibe | Known genetic mutations/polymorphisms that affect plasma lipids |

| Patients with narrowing of ≥20% in 1 coronary artery by invasive angiography or MDCTA | |

| Written informed consent |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; EVAPORATE, Effect of Vascepa on Improving Coronary Atherosclerosis in People With High Triglycerides Taking Statin Therapy study; HF, heart failure; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; MDCTA, multi‐detector computed tomography angiography; MI, myocardial infarction; TG, triglycerides.

2.3. Study endpoints

The primary endpoint is the rate of change in low‐attenuation plaque volume (defined as −50 to 50 Hounsfield units [HU]; see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article for details) from baseline to final assessment as measured by MDCTA. Secondary endpoints are shown in Table 2. These cutoff values were initially based on Brodoefel and empirically optimized using 3 representative training sets.

Table 2.

EVAPORATE study endpoints

| Primary endpoint |

| Change in low‐attenuation plaque volume as measured by MDCTA and defined as −50 to 50 HU |

| Secondary endpoints |

| Incident plaque rates; quantitative changes in different plaque types and morphology |

| Changes in markers of inflammation including Lp‐PLA2 and hsCRP |

| Changes in lipids and lipoproteins including standard lipid panel, lipoproteins, remnants, Apo‐A1/remnant ratio, EPA, AA, and EPA/AA ratio |

| Relationship between changes in the above with noncalcified coronary plaque burden and/or plaque‐vulnerability features |

Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; Apo‐A1, apolipoprotein A1; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; EVAPORATE, Effect of Vascepa on Improving Coronary Atherosclerosis in People With High Triglycerides Taking Statin Therapy study; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; HU, Hounsfield units; Lp‐PLA2, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2; MDCTA, multidetector computed tomography angiography.

2.4. Statistical design and analysis

Assuming 80% power and an α of 0.05, a total of 70 patients (35 per arm) are needed to evaluate the primary outcome of the study (East, version 6.3; Cytel, Cambridge, MA). Assuming a 15% dropout rate, a total of 80 (40 per arm) patients are to be enrolled. The initial study sample size was estimated based on MDCTA data showing 24% ± 13% reduction in coronary artery plaque volume with moderate‐dose statin therapy.15 It is assumed that an 8% reduction in plaque volume (one‐third that seen with statin therapy) would be the minimally important change in noncalcified plaque volume based on past data; multiple studies have shown similar progression/regression rates with different therapies.16, 17, 18, 19 Further data have been obtained using low‐attenuation plaque volume in both MDCTA and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) studies. In an integrated backscatter IVUS (IB‐IVUS) study by Niki et al., a statistically significant lipid volume decrease was seen at 6 months in the EPA + statin group from 18.5 mm3 (baseline) to 15.0 mm3 (follow‐up), vs an increase from 17.8 mm3 (baseline) to 19.3 mm3 (follow‐up) in those treated with statin alone (P = 0.013 for difference between EPA vs control).20 In the Combination Therapy of Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Pitavastatin for Coronary Plaque Regression Evaluated by Integrated Backscatter Intravascular Ultrasonography (CHERRY) study, plaque regression was defined as >14.6% decrease based on percent change in plaque volume observed in a cohort of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients undergoing percutaneous intervention and sequential IVUS evaluation over 6 months.21 The prevalence of total atheroma volume regression was significantly higher in the EPA + pitavastatin group vs the pitavastatin‐alone group (81% vs 61%; P < 0.002 for difference).22 In the EPA arms in these 2 studies, plaque lipid volume decreased by approximately 11% to 19%. In an MDCTA study of EPA vs ezetimibe, there was a decrease in what was believed to be the percent lipid or fatty plaque volume from 29.2 to 25.1 (−14%, calculated by percent change from baseline to follow‐up in plaque volume ranging from −50 to 50 HU for EPA‐treated groups); the same range of −50 to 50 HU will be used in the EVAPORATE study to represent low‐attenuation plaque volume (for additional details see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article).

Assuming an average of 1.7 measurable plaques per patient, with intrapatient plaque correlation of 0.24,23 70 patients would provide power of 0.80 and a 1‐sided type 1 error of 0.05 to detect an 8% difference in plaque volume between the active and placebo groups.

The primary analysis will utilize intent‐to‐treat principles, with study subjects analyzed by assigned treatment group regardless of study drug adherence. Changes from baseline will be calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical tests for outcomes will report 1‐sided P values (α: <0.048).

An interim analysis will be conducted at 9 months using the Lan‐DeMets version of the O'Brien‐Fleming group sequential boundaries for a 2‐look sequential design (1 interim at 9 months + final analysis). For the interim analysis, the statistical power to test the primary study endpoint is 80% based on a sample size of 70 patients randomized in a 1:1 allocation ratio and an overall experimental type 1 error equal to 0.05 using a 1‐sided hypothesis test. If a P value of ≤0.006 is achieved at 9 months, then the study will terminate because the efficacy boundary will have been achieved.

A sensitivity analysis will be performed on the group of patients adhering to interventions for >80% of the duration of the study. Baseline analysis and comparison between treatment arms will include demographics, coronary risk factors, atherosclerotic CV disease risk factors, laboratory tests, coronary calcium, and coronary plaque volume/composition.

Baseline characteristics will be presented as mean and SD or median and interquartile range. Differences in baseline characteristics between groups will use analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normally distributed continuous traits and the χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. For normally distributed continuous outcomes, including percent change in low‐attenuation plaque, mean percent group differences will be estimated using linear mixed models with baseline value, time, and treatment group as fixed effects. Least squares means will be estimated from the models. Models evaluating per‐patient outcomes will include fixed effects. Natural log‐transformations will be used for variables with log‐normal distributions. For the analyses of the primary and secondary efficacy variables, the statistical modeling assumptions will be examined. If significant departures from normality (P < 0.01 for the Shapiro–Wilk test) and/or homogeneity of variance are observed, the nonparametric analysis approach will be considered. When parametric and nonparametric results do not corroborate each other, the results from the nonparametric analysis will be used. Otherwise, the parametric analysis will be reported.

2.5. Compliance

After randomization, participants will be evaluated at 3, 9, and 12 months, and, if needed, at 15 months (by phone) and 18 months to assess compliance with study medication. Patients will return with pill bottles, and counts of remaining medications will be made at each visit.

2.6. Ethical considerations and study organization

The study is being conducted in compliance with institutional review boards/institutional ethics committees, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and relevant local laws and regulations. All patients will provide written informed consent. The Data Safety Monitoring Board will meet at 6‐month intervals to monitor study progress, safety, and efficacy. Study organization and leadership details are available in Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article.

2.7. Study status

At the time of writing of this manuscript, the study was approximately 50% enrolled with an estimated study completion in the third quarter of 2019.

3. DISCUSSION

Multiple lines of evidence support a strong rationale for the biologic plausibility of EPA as an antiatherosclerotic agent capable of improving CV outcomes and reducing residual risk on top of statin therapy by directly affecting atherosclerotic plaque. However, many of these supporting studies were in Japanese populations without elevated TG levels. The EVAPORATE study, which uses medical imaging to follow atherosclerosis, is specifically designed to evaluate the effects of high‐purity prescription EPA (icosapent ethyl) 4 g/d on atherosclerotic plaque using state‐of‐the‐art MDCTA imaging in a North American population of statin‐treated patients with elevated TG levels (200–499 mg/dL).

The present trial was designed using a number of markers that have never been studied in the context of low‐attenuation plaque following treatment with EPA in a Western population. These include serum EPA levels and the EPA/arachidonic acid (AA) ratio, both of which have been shown to beneficially affect plaque and CV events in a Japanese population.24 However, a meta‐analysis of large randomized controlled studies suggests that blood levels of AA may have an inverse relationship with CV outcomes.25 The meta‐analysis did not evaluate the relationship between the EPA/AA ratio and CV outcomes; therefore, the significance of these findings on the present study is not known. Additionally, studies of the apolipoprotein A1/remnant ratio have been limited,26, 27 and the relationship between this ratio and low‐attenuation plaque has not yet been published to our knowledge.

Prior imaging studies of the effects of EPA on atherosclerotic plaque using angiography, IVUS, IB‐IVUS, carotid ultrasound, and optical coherence tomography have begun to elucidate the role of EPA intervention in atherosclerotic disease8; data regarding MDCTA are presently limited to congress abstracts and non‐Western populations.28, 29 In a study of 43 Japanese patients with 51 lesions and suspected coronary artery disease, patients were treated with either EPA or ezetimibe; MDCTA evaluations were conducted at baseline and at 1 year.28 EPA‐treated patients experienced significant reductions in soft‐plaque volume compared with ezetimibe‐treated patients (−50 to 0 HU component; P = 0.036 for difference between EPA and ezetimibe).28 Significant reductions in plaque area (P = 0.017) and lumen area (P = 0.004) were also observed in the EPA‐treated group compared with the ezetimibe group.28 Additionally, the incidence of major coronary events was significantly lower (P = 0.03) in the EPA group (9.5%) compared with the ezetimibe group (36.4%).28 The data suggest that EPA played a beneficial role in coronary plaque stabilization. Another Japanese study assessed plaque progression in ACS patients treated with EPA (n = 33) or EPA + docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; n = 29) and in untreated control patients (n = 20) via serial CCTA at baseline and at 1 year.29 All patients were on statin therapy after the baseline assessment. After 1 year, there was a significant difference in the progression of plaque between the 3 groups (P = 0.0061), with progression observed in 3%, 14%, and 35% of patients in the EPA, EPA + DHA, and control groups, respectively.29 Another study worth noting is the recent HEARTS study of statin‐treated patients with stable coronary artery disease and well‐controlled LDL‐C, which demonstrated that high‐dose EPA + DHA prevented the progression of fibrous coronary plaque volume over 30 months compared with statin alone using CCTA.30

The use of MDCTA allows for the noninvasive examination of plaque composition, severity of vessel stenosis, plaque volume, and extent of remodeling.31 MDCTA also can measure plaque burden.32 The technique is now used in clinical investigations evaluating a range of therapies including testosterone, garlic, statins, hormone replacement, anti‐inflammatory agents, and antidiabetes agents. MDCTA yields high reproducibility of measurements33 and allows for evaluation of the entire coronary tree. Although MDCTA is a relatively new technique, it has been shown to have high reproducibility, with <1% variability for measuring noncalcified and calcified plaque volume and <15% variability for total plaque.34 MDCTA also has been shown to correlate with IVUS in measuring lipid plaque volume.35, 36 In addition, a study by Nakanishi et al37 showed for the first time that nonobstructive low‐attenuation plaques, visualized on MDCT, were associated with ACS events during 3 years of follow‐up in patients with hypertension and were a more powerful predictor than traditional risk factors, including Framingham risk score, carotid intima‐media thickness, and left ventricular mass index.

Cardiovascular outcomes in North American patients treated with high‐dose icosapent ethyl (4 g/d) are being investigated in the Reduction of Cardiovascular Events With Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention Trial (REDUCE‐IT; NCT01492361).38 REDUCE‐IT is a phase 3b, international, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study that is evaluating whether treatment with icosapent ethyl reduces ischemic events in a statin‐treated patient population similar to that of the EVAPORATE study (TG levels ≥150 mg/dL and <500 mg/dL, LDL‐C levels >40 mg/dL and ≤100 mg/dL, and at elevated CV risk). Of note, whereas EVAPORATE will utilize medical imaging data, REDUCE‐IT focuses on clinical CV event outcomes.38 REDUCE‐IT has randomized approximately 8000 patients and is nearing completion, with final results anticipated to be reported during 2018.38 The populations studied in EVAPORATE and REDUCE‐IT represent a relatively large population: based on approximations from large CV outcomes trials including or limited to patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, roughly 25% to 40% of patients had TG levels ≥150 mg/dL and LDL‐C levels <100 mg/dL, and roughly 15% to 20% of patients had TG levels ≥200 mg/dL and LDL‐C levels <100 mg/dL.39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Another study of interest is the ongoing global Statin Residual Risk Reduction with Epanova in High CV Risk Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia trial (STRENGTH; NCT02104817), which is evaluating the effects of a DHA + EPA combination product (omega‐3 carboxylic acids; high dose) on CV outcomes in patients with TG levels ≥180 mg/dL and <500 mg/dL and LDL‐C levels <100 mg/dL. As STRENGTH will be evaluating the combination of EPA and DHA, the findings from EVAPORATE may not directly or indirectly inform the findings.

The findings of the EVAPORATE study will add to our understanding of the role of EPA intervention in the treatment of atherosclerotic plaque in that the study will assess statin‐treated patients using MDCTA and high‐purity EPA (icosapent ethyl) at a dose known to raise plasma EPA to levels similar to those observed in JELIS, which demonstrated significant reduction in risk of major coronary events in Japanese patients. EVAPORATE may also contribute to the understanding of the pathophysiologic underpinnings of the results of the EPA‐only REDUCE‐IT study.

4. CONCLUSION

EVAPORATE will be the first study using MDCTA to evaluate the effects of icosapent ethyl on atherosclerotic plaque as an adjunct to statin therapy in a North American population with persistent high TG levels, and it will assess whether these effects correlate with lipid changes and inflammatory markers. The clinical implications of icosapent ethyl 4 g/d as an adjunct to statin therapy on CV endpoints are also being evaluated in the large CV outcomes study REDUCE‐IT. EVAPORATE will provide important mechanistic data that may have relevance to the REDUCE‐IT results.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Appendix (On‐line)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The EVAPORATE trial is sponsored by Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute, with the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation as the collaborator. Amarin Pharma Inc., Bedminster, New Jersey, funded the trial and provided the trial drugs but had/will have no role in the design or conduct of the trial or the analysis of the data. Medical‐writing assistance was provided by Peloton Advantage, LLC, Parsippany, New Jersey, and was funded by Amarin Pharma Inc. Medical scientific reference checks and associated assistance were provided by Sephy Philip, RPh, PharmD, and Megan Montgomery, PhD, of Amarin Pharma Inc. Amarin Pharma Inc. had no role in the approval of this manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Budoff, speakers bureau for Amarin. Dr. Nelson, speakers bureau, advisory board, and stock in Amarin; speakers bureau and research support from Boston Heart Diagnostics. The authors declare no other potential conflicts of interest.

Budoff M, Brent Muhlestein J, Le VT, May HT, Roy S, Nelson JR. Effect of Vascepa (icosapent ethyl) on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with elevated triglycerides (200–499 mg/dL) on statin therapy: Rationale and design of the EVAPORATE study. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:13–19. 10.1002/clc.22856

Funding information The EVAPORATE trial is funded by Amarin Pharma Inc., Bedminster, New Jersey.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fruchart JC, Davignon J, Hermans MP, et al; Residual Risk Reduction Initiative. Residual macrovascular risk in 2013: what have we learned? Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Borow KM, Nelson JR, Mason RP. Biologic plausibility, cellular effects, and molecular mechanisms of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242:357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Toth PP. Triglyceride‐rich lipoproteins as a causal factor for cardiovascular disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2016;12:171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tanaka N, Ishida T, Nagao M, et al. Administration of high dose eicosapentaenoic acid enhances anti‐inflammatory properties of high‐density lipoprotein in Japanese patients with dyslipidemia. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanaka N, Irino Y, Shinohara M, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid–enriched high‐density lipoproteins exhibit anti‐atherogenic properties. Circ J. 2017. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bays HE, Ballantyne CM, Kastelein JJ, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in patients with very high triglyceride levels (from the Multi‐Center, Placebo‐Controlled, Randomized, Double‐Blind, 12‐Week Study With an Open‐Label Extension [MARINE] trial). Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:682–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Kastelein JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in statin‐treated patients with persistent high triglycerides (from the ANCHOR study). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:984–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nelson JR, Wani O, May HT, et al. Potential benefits of eicosapentaenoic acid on atherosclerotic plaques. Vascul Pharmacol. 2017;91:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, et al; JELIS Investigators. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open‐label, blinded endpoint analysis [published correction appears in Lancet. 2007;370:220]. Lancet. 2007;369:1090–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vascepa [package insert]. Bedminster, NJ: Amarin Pharma Inc.; 2017.

- 11. Bays HE, Ballantyne CM, Doyle RT Jr, et al. Icosapent ethyl: eicosapentaenoic acid concentration and triglyceride‐lowering effects across clinical studies. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2016;125:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bays HE, Ballantyne CM, Braeckman RA, et al. Icosapent ethyl, a pure ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid: effects on circulating markers of inflammation from the MARINE and ANCHOR studies. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2013;13:37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Philip S, et al. Icosapent ethyl (eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester): effects on remnant‐like particle cholesterol from the MARINE and ANCHOR studies. Atherosclerosis. 2016;253:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Braeckman RA, et al. Icosapent ethyl (eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester): effects on plasma apolipoprotein C‐III levels in patients from the MARINE and ANCHOR studies. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:635.e1–645.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burgstahler C, Reimann A, Beck T, et al. Influence of a lipid‐lowering therapy on calcified and noncalcified coronary plaques monitored by multislice detector computed tomography: results of the New Age II Pilot Study. Invest Radiol. 2007;42:189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsumoto S, Ibrahim R, Grégoire JC, et al. Effect of treatment with 5‐lipoxygenase inhibitor VIA‐2291 (atreleuton) on coronary plaque progression: a serial CT angiography study. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:210–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsumoto S, Nakanishi R, Li D, et al. Aged garlic extract reduces low attenuation plaque in coronary arteries of patients with metabolic syndrome in a prospective randomized double‐blind study. J Nutr. 2016;146:427S–432S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakanishi R, Ceponiene I, Osawa K, et al. Plaque progression assessed by a novel semi‐automated quantitative plaque software on coronary computed tomography angiography between diabetes and non‐diabetes patients: a propensity‐score matching study. Atherosclerosis. 2016;255:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeb I, Li D, Nasir K, et al. Effect of statin treatment on coronary plaque progression—a serial coronary CT angiography study. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Niki T, Wakatsuki T, Yamaguchi K, et al. Effects of the addition of eicosapentaenoic acid to strong statin therapy on inflammatory cytokines and coronary plaque components assessed by integrated backscatter intravascular ultrasound. Circ J. 2016;80:450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dohi T, Miyauchi K, Okazaki S, et al. Plaque regression determined by intravascular ultrasound predicts long‐term outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Watanabe T, Ando K, Daidoji H, et al; CHERRY Study Investigators. A randomized controlled trial of eicosapentaenoic acid in patients with coronary heart disease on statins. J Cardiol. 2017;70:537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibson CM, Sandor T, Stone PH, et al. Quantitative angiographic and statistical methods to assess serial changes in coronary luminal diameter and implications for atherosclerosis regression trials. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1286–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohnishi H, Saito Y. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) reduces cardiovascular events: relationship with the EPA/arachidonic acid ratio. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2013;20:861–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S, et al. Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta‐analysis [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:658]. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. May HT, Nelson JR, Kulkarni KR, et al. A new ratio for better predicting future death/myocardial infarction than standard lipid measurements in women >50 years undergoing coronary angiography: the apolipoprotein A1 remnant ratio (Apo A1/ [VLDL(3)+IDL]). Lipids Health Dis. 2013;12:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morishita T, Uzui H, Ikeda H, et al. Association of CD34/CD133/VEGFR2‐positive cell numbers with eicosapentaenoic acid and postprandial hyperglycemia in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:1039–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shintani Y, Kawasaki T. The impact of a pure‐EPA omega‐3 fatty acid on coronary plaque stabilization: a plaque component analysis with 64‐slice multi‐detector row computed tomography [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:E1731. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagahara Y, Motoyama S, Sarai M, et al. The impact of eicosapentaenoic acid on prevention of plaque progression detected by coronary computed tomography angiography [abstract P5235]. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(suppl 1):1052. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alfaddagh A, Elajami T, Welty F. Omega‐3 fatty acid added to statin prevents progression of fibrous coronary artery plaque compared to statin alone in patients with coronary artery disease [abstract]. Circulation. 2016;134:A16294. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoffmann U, Moselewski F, Nieman K, et al. Noninvasive assessment of plaque morphology and composition in culprit and stable lesions in acute coronary syndrome and stable lesions in stable angina by multidetector computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1655–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boogers MJ, Broersen A, van Velzen JE, et al. Automated quantification of coronary plaque with computed tomography: comparison with intravascular ultrasound using a dedicated registration algorithm for fusion‐based quantification. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Budoff MJ, Ellenberg SS, Lewis CE, et al. Testosterone treatment and coronary artery plaque volume in older men with low testosterone. JAMA. 2017;317:708–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamirani YS, Kadakia J, Pagali SR, et al. Assessment of progression of coronary atherosclerosis using multidetector computed tomography angiography (MDCT). Int J Cardiol. 2011;149:270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leber AW, Becker A, Knez A, et al. Accuracy of 64‐slice computed tomography to classify and quantify plaque volumes in the proximal coronary system: a comparative study using intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yamaki T, Kawasaki M, Jang IK, et al. Comparison between integrated backscatter intravascular ultrasound and 64‐slice multi‐detector row computed tomography for tissue characterization and volumetric assessment of coronary plaques. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;10:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakanishi K, Fukuda S, Shimada K, et al. Non‐obstructive low attenuation coronary plaque predicts three‐year acute coronary syndrome events in patients with hypertension: multidetector computed tomographic study. J Cardiol. 2012;59:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Brinton EA, et al. Rationale and design of REDUCE‐IT: Reduction of Cardiovascular Events With Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention Trial. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:138–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Faergeman O, Holme I, Fayyad R, et al; Steering Committees of IDEAL and TNT trials. Plasma triglycerides and cardiovascular events in the Treating to New Targets and Incremental Decrease in End‐Points Through Aggressive Lipid‐Lowering trials of statins in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Landray MJ, Haynes R, Hopewell JC, et al; HPS2‐THRIVE Collaborative Group . Effects of extended‐release niacin with laropiprant in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miller M, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, et al; PROVE IT‐TIMI 22 Investigators . Impact of triglyceride levels beyond low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol after acute coronary syndrome in the PROVE IT‐TIMI 22 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORD Study Group . Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1748]. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1563–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guyton JR, Slee AE, Anderson T, et al. Relationship of lipoproteins to cardiovascular events: the AIM‐HIGH trial (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome With Low HDL/High Triglycerides and Impact on Global Health Outcomes). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1580–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Appendix (On‐line)