This randomized clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and safety of transcranial direct current stimulation as add-on therapy in patients with bipolar depression.

Key Points

Question

Is transcranial direct current stimulation a safe and effective add-on therapy for bipolar depression?

Finding

In this randomized clinical trial of 59 participants receiving a stable pharmacologic regimen, active transcranial direct current stimulation was associated with superior depression improvement and higher response rates than sham. Moreover, active transcranial direct current stimulation did not induce more manic/hypomanic episodes compared with sham.

Meaning

Transcranial direct current stimulation is an affordable therapy with few adverse events that showed efficacy as an add-on treatment of bipolar depression.

Abstract

Importance

More effective, tolerable interventions for bipolar depression treatment are needed. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a novel therapeutic modality with few severe adverse events that showed promising results for unipolar depression.

Objective

To determine the efficacy and safety of tDCS as an add-on treatment for bipolar depression.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind trial (the Bipolar Depression Electrical Treatment Trial [BETTER]) was conducted from July 1, 2014, to March 30, 2016, at an outpatient, single-center academic setting. Participants included 59 adults with type I or II bipolar disorder in a major depressive episode and receiving a stable pharmacologic regimen with 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) scores higher than 17. Data were analyzed in the intention-to-treat sample.

Interventions

Ten daily 30-minute, 2-mA, anodal-left and cathodal-right prefrontal sessions of active or sham tDCS on weekdays and then 1 session every fortnight until week 6.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Change in HDRS-17 scores at week 6.

Results

Fifty-nine patients (40 [68%] women), with a mean (SD) age of 45.9 (12) years participated; 36 (61%) with bipolar I and 23 (39%) with bipolar II disorder were randomized and 52 finished the trial. In the intention-to-treat analysis, patients in the active tDCS condition showed significantly superior improvement compared with those receiving sham (βint = −1.68; number needed to treat, 5.8; 95% CI, 3.3-25.8; P = .01). Cumulative response rates were higher in the active vs sham groups (67.6% vs 30.4%; number needed to treat, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.84-4.99; P = .01), but not remission rates (37.4% vs 19.1%; number needed to treat, 5.46; 95% CI, 3.38-14.2; P = .18). Adverse events, including treatment-emergent affective switches, were similar between groups, except for localized skin redness that was higher in the active group (54% vs 19%; P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this trial, tDCS was an effective, safe, and tolerable add-on intervention for this small bipolar depression sample. Further trials should examine tDCS efficacy in a larger sample.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02152878

Introduction

Bipolar disorder presents a high burden. Depressive episodes are more frequent, prolonged, and incapacitating compared with manic ones. Therapeutic options for bipolar depression (BD) have adverse effects and modest efficacy. Electroconvulsive therapy, although effective for BD, requires sedation, short-term hospitalization, and pharmacologic adjustments. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, a noninvasive brain stimulation approach, showed positive results for unipolar depression and BD. However, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation is expensive and associated with seizures.

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is another noninvasive brain stimulation modality that applies weak, direct currents into the brain via electrodes that are placed over the scalp. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and tDCS are usually applied over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), a brain area whose metabolism increases after successful antidepressant treatment. Moreover, the DLPFC, part of the frontoparietal network that is responsible for cognitive control and emotion regulation, is hypoactive in depression. Antidepressant effects of noninvasive brain stimulation might involve, according to the factors of stimulation, modulation of the DLPFC and other brain structures implicated in the depression pathophysiology via enhancement of synaptic plasticity and metabolic activity, as well as excitability changes.

Meta-analyses and randomized sham-controlled trials showed tDCS efficacy for unipolar depression. Moreover, tDCS has clinical advantages, such as low cost, portability, and ease of use.

However, to our knowledge, no randomized sham-controlled trial using tDCS has been conducted for BD. Therefore, we examined the efficacy and safety of tDCS as an add-on therapy in patients with BD who were receiving concurrent pharmacologic therapies in the Bipolar Depression Electrical Treatment Trial (BETTER). We hypothesized that active vs sham tDCS would have greater antidepressive effects, as measured by changes in the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) scores, after 6 weeks of treatment. The secondary outcomes were to compare the effects of treatment on other depression scales, cumulative response and remission rates, and rate of adverse events (AEs), particularly episodes of treatment-emergent affective switch (TEAS), between groups. We hypothesized that active compared with sham tDCS would also effect greater depression improvement in the other efficacy outcomes and that both groups would present similar AE rates.

Methods

BETTER was conducted at University Hospital, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, from July 1, 2014, to March 30, 2016. BETTER used a parallel design in which 59 patients were randomly assigned to sham or active tDCS per a computer-generated list, using random block sizes. We used opaque, sealed envelopes with a corresponding code for group allocation. The study protocol was previously published and executed with no significant changes; the protocol is also available in Supplement 1. The study was approved by the local (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa do Hospital Universitário da USP and Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da USP) and national (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa) ethics committees and reported according to CONSORT guidelines. All participants signed informed consent forms that met the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines; there was no financial compensation.

Participants

Participants were recruited through media advertisements and physician referrals. They were prescreened by brief telephone and email interviews, and those who met the general criteria were subjected to additional on-site screening. All participants were screened on site by trained, board-certified psychiatrists (5 of us: B.S.-J., L.B., E.C., L.V.A., and I.K.) who used the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview to perform the diagnosis of bipolar disorder (type I or II or not otherwise specified) in a major depressive episode and other comorbid mental disorders, such as anxiety disorders and the disorders listed as exclusion criteria in the study. Only those with HDRS-17 scores higher than 17 and low suicide risk (evaluated clinically and using the corresponding Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview questionnaire) and aged between 18 and 65 years were included.

We included only patients who presented lack of clinical response after 1 or more adequate pharmacologic interventions in the acute depressive episode. Thus, those who were receiving previous pharmacotherapy for the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder and presented an untreated depressive episode were not included.

For adequate pharmacologic intervention, we considered first-, second-, or third-line pharmacotherapies per Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for bipolar I and II depressive episodes: lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, olanzapine, valproate sodium, and electroconvulsive therapy were considered to be valid overall for bipolar I and II depressive episodes, whereas antidepressant monotherapy (for patients without episodes of hypomania/mania in the past 5 years and no history of affective switches or mixed depressive episodes) and carbamazepine were considered to be valid third-line therapeutic interventions for bipolar II and I depressive episodes, respectively.

The use of benzodiazepines was allowed but tapered to a maximum of diazepam, 20 mg/d, or its equivalent. We included only patients who had been receiving a fixed pharmacologic regimen for 4 weeks, which remained stable during the trial. All drugs were being used in their recommended dose range for BD, including blood levels within the therapeutic range for maintenance when applicable.

Exclusion criteria were demonstrating a depressive episode with mixed features; other psychiatric disorders, such as unipolar major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, substance dependence and abuse, and dementias; personality disorders; neurologic disorders; pregnancy; specific contraindications to tDCS (eg, metal plates in head); and participation in previous tDCS trials. The only psychiatric comorbidities allowed were anxiety disorders.

Patient losses occurred if they (1) missed 3 nonconsecutive sessions or 2 consecutive sessions during the initial 10-day stimulation period; (2) did not return at weeks 4 and 6; (3) presented serious clinical or psychiatric events during the trial, such as seizures, suicidal attempt/ideation, or full-blown manic or hypomanic episode; (4) were excluded for safety reasons, including severe worsening of psychiatric condition or serious AEs; or (5) withdrew participation at their request.

In cases of possible exclusion due to safety reasons or serious clinical or psychiatric events, participants would be evaluated separately by a psychiatrist from the hospital who was not participating in the study. Such cases, however, did not occur during the trial.

Intervention

Patients lay in comfortable, reclinable chairs to receive tDCS (devices, sponges, and headgears [EASYstrap]; SoterixMedical), performed by blinded, trained nurses. Patients received no specific instructions during the sessions; they could read or use their smartphones, but not fall asleep. Communication with staff was minimal. The anode and cathode electrodes were inserted in 5 × 5-cm saline-soaked sponges and placed over the left and right DLPFC, respectively. The EASYstrap was used for positioning the electrodes over the DLPFC bilaterally per the omnilateral electrode system, which is optimized for peak electric current densities over the DLPFC, compared with other methods, such as the electroencephalographic International 10-20 System.

Twelve 2-mA sessions (current density, 0.80 A/m2, ramp-up and ramp-down periods of 30 and 15 seconds, respectively) were applied for 30 minutes each day over 10 consecutive sessions once daily from Monday through Friday, with weekends off, and 2 sessions were applied at weeks 4 and 6 (study end point). Patients were granted 2 missing visits during the initial phase, which were replaced at the end to complete 10 sessions, as described elsewhere.

The same treatment schedule was used in previous studies, making the results comparable. The end point at week 6 was chosen because tDCS effects tend to increase over time and are usually not significant after the acute treatment phase. The extra sessions at weeks 4 and 6 were planned for enhancing clinical effects and adherence.

The tDCS devices had a keypad on which a 6-digit code was entered to deliver active or sham stimulation. Sham tDCS was delivered using the same protocol and current intensity, but the period of active stimulation was only 30 seconds. Blinding was assessed at the study end point by asking participants to guess to which group they were assigned.

Outcomes

All assessments were performed by trained, blinded psychiatrists and psychologists. Participants were assessed at baseline, week 2, week 4, and the end point (week 6). Adverse events were recorded at weeks 2 and 6.

The primary outcome was the change in HDRS-17 score between groups over time. Secondary outcomes included (1) changes in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) depression scale scores; (2) rates of AEs, evaluated per a commonly used tDCS AE questionnaire and the Young Mania Rating Scale; (3) sustained clinical response (defined as a sustained >50% reduction from baseline HDRS-17 score from all weeks greater than 2, or 4, or 6, since the time that a >50% reduction was first achieved) and remission (sustained HDRS-17 score ≤7 from all weeks greater than 2, or 4, or 6, since the time an HDRS-17 score ≤7 was first achieved). Therefore, patients who presented more than a 50% reduction from baseline scores or HDRS-17 ≤ 7 at weeks 2 and/or 4, but not at week 6, were not classified as presenting a sustained clinical response or remission, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was estimated for a power of 80% and a 2-tailed α level of 5%. The effect size and variability of the difference between active tDCS and sham were based on the results of the meta-analysis available when this study was conceived (Hedges g, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.21-1.27) and in a unipolar tDCS trial (difference of 5.6 points; 95% CI, 1.3-10), which means that any effect size lower than these values would not be considered clinically significant. We obtained total sample sizes of 55 and 52 participants, respectively. After that, we considered an attrition rate of 10% to 15%, increasing the targeted sample size to 58 to 60 participants. Data were analyzed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) sample.

For continuous outcomes, we performed hierarchical linear model analyses, assuming a linear relationship over time with 4 repeated measurements per person, because patients were tested in regular intervals of 2 weeks. Measurements closer in time were considered to be more highly correlated than measurements further apart; thus, an autoregressive covariance structure was assumed. Time and tDCS as well as their interaction served as independent variables in the model. This model uses all available observed variables without the need to utilize other imputation methods for intention-to-treat analysis.

Our hypothesis was that the interaction of time with tDCS would be significant, with active tDCS showing significantly superior symptomatic decrease over time. Parameters were computed using maximum likelihood estimation to permit comparisons of nested models with χ2 likelihood ratio tests. Models were computed with Satterthwaite approximation to degrees of freedom.

Sustained response and remission curves of the interventions were compared using failure (to account for events increasing over time) Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Data on patients lost to follow-up were examined only during the known period of observation. According to our definition of sustained response/remission, the event could only occur once. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratios associated with the intervention.

The frequency of symptoms that were suggestive of TEAS, defined as Young Mania Rating Scale scores higher than 8, and AEs were compared between groups by Fisher exact test or χ2 test.

Effect size was calculated as number needed to treat (NNT) for all outcomes. For continuous outcomes, effect sizes as well as their 95% CIs were estimated based on the model residual SD and then transformed to NNT using the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. For survival analyses, NNT was estimated based on a previous study. Number needed to treat assesses the effectiveness of clinical interventions, wherein a higher NNT reflects a less effective intervention. Analyses were performed using Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp) and R, version 3.4.0 (lme4 package; R Foundation). Results were significant at P < .05.

Results

Participants

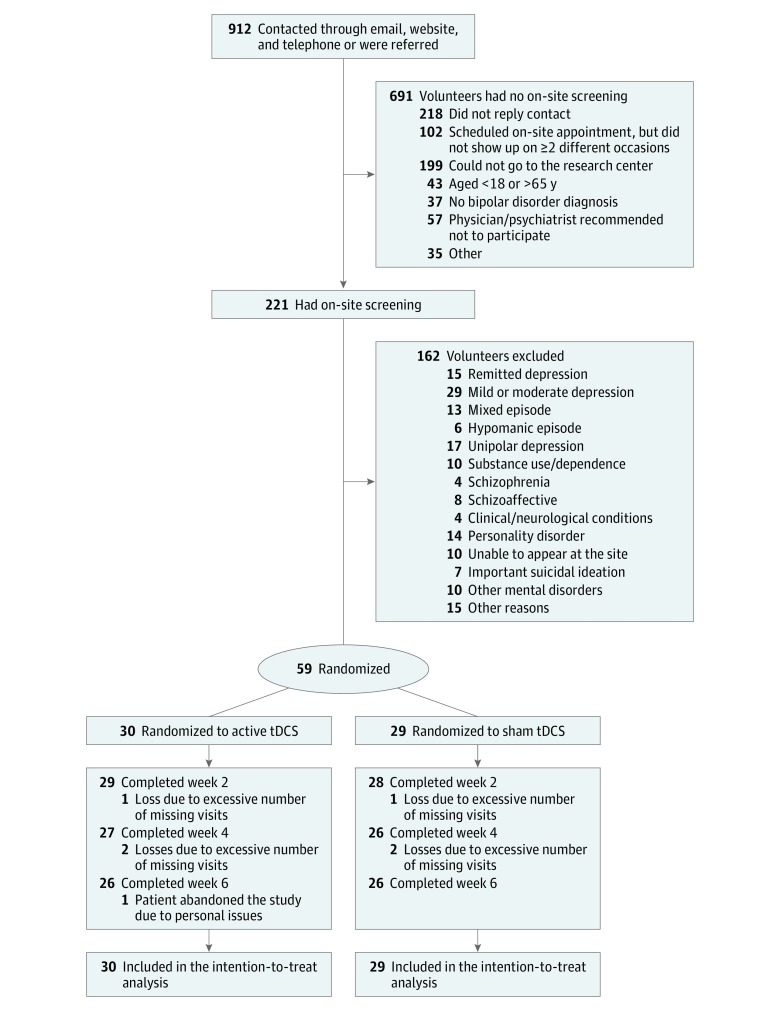

Of 912 volunteers, 221 individuals were screened and 162 were excluded for several reasons. Of the 59 patients included, 52 (26 in each group) received all 12 tDCS sessions and completed the final assessment (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Participant Selection.

There were 3 patient losses in the sham group (all due to excessive number of missed visits) and 4 patient losses in the active group (3 excessive number of missed visits, 1 withdrawal due to personal issues). tDCS indicates transcranial direct current stimulation.

Table 1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample at Baseline.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (n = 29) |

Active tDCS (n = 30) |

Total (N = 59) |

|

| Demographics | |||

| Women | 24 (83) | 16 (53) | 40 (68) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 45.7 (10.3) | 46.2 (11.8) | 45.9 (12) |

| Years at school, mean (SD) | 17.4 (6.6) | 15.7 (4.0) | 16.6 (5.5) |

| Income, <5 monthly wages, R$a | 11 (38) | 7 (23) | 18 (30) |

| Whiteb | 15 (52) | 23 (77) | 38 (64) |

| Not married | 17 (59) | 11 (37) | 28 (47) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.7 (8) | 27.8 (5) | 27.7 (6) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Onset age, mean (SD), y | 20.2 (8) | 23.5 (11) | 21.8 (9.8) |

| Bipolar disorder | |||

| Type I | 16 (55) | 20 (67) | 36 (61) |

| Type II | 13 (45) | 10 (33) | 23 (39) |

| Previous episodes, mean (SD), No. | 17.6 (10.8) | 15.2 (12.1) | 16.4 (11.4) |

| >12-mo Duration | 8 (28) | 10 (33) | 18 (31) |

| Severe depression | 14 (48) | 14 (47) | 28 (47) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 22 (76) | 24 (80) | 46 (78) |

| Panic disorder | 3 (10) | 1 (3) | 4 (7) |

| Social anxiety disorder | 6 (21) | 6 (20) | 12 (20) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 25 (86) | 26 (87) | 51 (86) |

| Treatment history | |||

| Failed treatments, mean (SD) | 5.1 (1.2) | 5.2 (1.6) | 5.1 (1.4) |

| Treatment-resistant bipolar depression | 8 (28) | 11 (37) | 19 (32) |

| Pharmacotherapies in the present episode | |||

| First-line treatments being used, mean (SD), No. | 1.2 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.3 (0.9) |

| Antidepressant drugs | |||

| SSRIs | 14 (48) | 9 (30) | 23 (39) |

| Venlafaxine | 2 (7) | 4 (13) | 6 (10) |

| Bupropion | 4 (14) | 4 (13) | 8 (14) |

| Any antidepressant drug | 23 (79) | 21 (70) | 44 (75) |

| Antidepressant monotherapyc | 0 | 3 (10) | 3 (5) |

| Mood stabilizersd | |||

| Lithium | 7 (24) | 13 (43) | 20 (34) |

| Valproate | 9 (31) | 9 (30) | 18 (31) |

| Lamotrigine | 8 (28) | 5 (17) | 13 (22) |

| Quetiapine | 7 (24) | 10 (33) | 7 (29) |

| Olanzapine | 4 (14) | 1 (3) | 5 (8) |

| Carbamazepinee | 1 (3) | 2 (7) | 3 (5) |

| Other treatmentsf | |||

| Benzodiazepinesg | 16 (55) | 3 (10) | 27 (46) |

| Other anticonvulsantsh | 4 (14) | 8 (27) | 12 (20) |

| Other SGAsi | 6 (21) | 3 (10) | 9 (15) |

| FGAsj | 1 (3) | 2 (7) | 3 (5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); FGA, first-generation antipsychotics; R$, Brazilian real; SGAs, second-generation antipsychotics; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

Conversion factor: R$1 equivalent to US $0.30.

Ethnicity was self-reported.

Third-line treatment for bipolar II depressive episode in those with infrequent hypomania per 2013 CANMAT (Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments) guidelines. The 3 patients presented a stable bipolar II depressive episode without prior affective switches and a hypomanic episode that occurred more than 5 years before the trial onset. None of the patients presented affective switches during the trial. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression was defined as lack of a clinical response for the bipolar depressive episode after 2 or more treatment regimens per CANMAT guidelines, at least 1 of them being a first-line treatment recommendation.

Recommended for bipolar depression treatment.

Third-line treatment for bipolar I depressive episode per 2013 CANMAT guidelines.

Including nonrecommended mood stabilizers and SGAs for bipolar depression.

Diazepam, clonazepam, lorazepam, bromazepam, midazolam, flunitrazepam, and zolpidem.

Gabapentin and topiramate.

Ziprasidone, aripiprazole, paliperidone, and risperidone.

Included haloperidol and chlorpromazine.

Primary Outcome

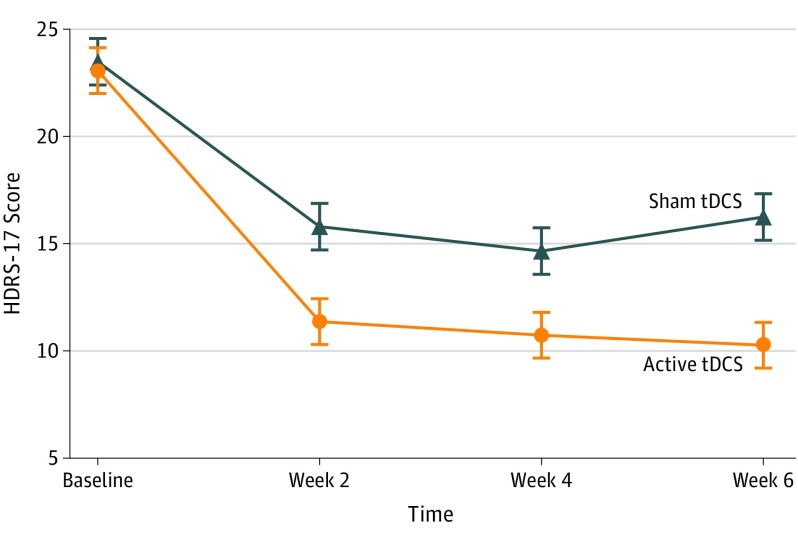

The primary outcome was HDRS-17 score change. Hierarchical linear model analysis revealed a significant time × group interaction (F1,166.05 = 6.46; P = .01) showing greater symptomatic decrease over time in the tDCS group (βint = −1.68; NNT, 5.8; 95% CI, 3.3-25.8). Optimal model fit was found for a random-intercept fixed-slope solution, because including symptomatic change as a random factor resulted in no significant improvement (χ22 = 1.66; P = .44) (Figure 2; eTable in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Change in Depression Scores Over Time.

Mean changes in 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) scores (intention-to-treat analysis) from baseline to end point. Active transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) was superior to sham. Error bars indicate 1 SD.

Secondary Outcomes

Remitters and Responders

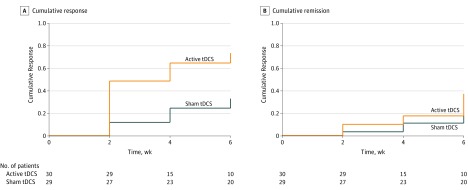

Respectively for the active and sham groups, 19 and 8 patients presented sustained response. The cumulative survival rates at end point per Kaplan-Meier analysis were 67.6% (95% CI, 50.1%-83.9%) and 30.4% (95% CI, 16.5%-51.8%). The Cox proportional hazards ratio associated with treatment group was 2.86 (SE, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.25-6.61; P = .01). The corresponding NTT was 2.69 (95% CI, 1.84-4.99) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Sustained Response and Remission Rates.

Survival analyses for sustained response (defined as a sustained >50% reduction from baseline 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS-17] score from all weeks greater than 2, 4, or 6, since the time that a >50% reduction was first achieved) (A) and sustained remission (sustained HDRS-17 score ≤7 from all weeks greater than 2, 4, or 6, since the time that an HDRS-17 score ≤7 was first achieved) (B).

Similarly, 10 and 5 patients in the active and sham groups, respectively, presented sustained remission. The cumulative survival rates were 37.4% (95% CI, 22%-58.5%) and 19.1% (95% CI, 8.4%-40%). The Cox proportional hazards ratio was 2.07 (SE, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.71-6.06; P = .18). The NTT was 5.46 (95% CI, 3.38-14.2) (Figure 3B).

Other Depression Measures

As in the primary outcome, a significant time × group interaction was found in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (F1,167.6 = 5.23; P = .02). Patients in the active group experienced significantly greater improvement over time compared with those in the sham group (βint = −1.99; NNT, 6.4; 95% CI, 3.5 to 47.1). Equivalently, including the slope as a random factor did not significantly improve the model fit (χ22 = 5.64; P = .06). For the CGI scale, no significant differences could be found in the trajectories of symptomatic decrease (F1,162.31 = 2.31; P = .13) (eTable in Supplement 2).

AEs and Safety

Skin redness rates were higher in the active (54%) than sham (19%) group (P = .01) at the end point. The frequency of other AEs did not significantly differ (Table 2). There were 9 TEAS episodes throughout the trial: 5 (19%) in the sham and 4 (15%) in the active group (χ2 = 0.13; P = .71). These episodes did not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode with mixed features, hypomania, or mania per DSM-5 guidelines and required no hospitalization, trial discontinuation, or specific treatment (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of Adverse Events at Least Remotely Associated With Interventiona.

| Adverse Event | Week 2 | Week 6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P Valueb | No. (%) | P Valueb | |||

| Sham (n = 26) |

Active (n = 27) |

Sham (n = 26) |

Active (n = 26) |

|||

| Headache | 12 (46) | 8 (30) | .21 | 6 (23) | 8 (31) | .53 |

| Neck pain | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | >.99 | 0 | 1 (4) | .32 |

| Discomfort, left side | 5 (19) | 7 (26) | .56 | 3 (12) | 5 (19) | >.99 |

| Discomfort, right side | 5 (19) | 7 (26) | .56 | 4 (15) | 5 (19) | >.99 |

| Tingling | 15 (58) | 15 (56) | .87 | 12 (46) | 14 (54) | .57 |

| Itching | 2 (9) | 7 (28) | .14 | 2 (8) | 8 (31) | .07 |

| Burning | 7 (30) | 11 (44) | .33 | 4 (15) | 8 (31) | .32 |

| Skin redness | 5 (19) | 11 (41) | .08 | 5 (19) | 14 (54) | .01 |

| Sleepiness | 10 (38) | 9 (33) | .69 | 9 (35) | 6 (23) | .35 |

| Trouble concentrating | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | >.99 | 0 | 1 (4) | >.99 |

| Fatigue | 1 (4) | 0 | .47 | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | >.99 |

| Nausea | 3 (13) | 2 (8) | .66 | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | >.99 |

| Dizziness | 2 (9) | 2 (8) | >.99 | 0 | 2 (8) | .49 |

| TEAS episode | NA | NA | NA | 5 (19) | 4 (15) | .71 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable; TEAS, treatment-emergent affective switch.

Adverse events were assessed using a commonly used tDCS questionnaire. At the end of weeks 2 and 6, all participants were asked to complete these questionnaires, describing the presence of an adverse event, its severity (mild, moderate, or severe), and its relationship to the treatment (1, none; 2, remote; 3, possible; 4, probable; or 5, certain).

P values were determined with χ2or Fisher exact test.

Integrity of Blinding

In the sham and active groups, respectively, 15 and 16 (of 26 participants for both) patients correctly identified the allocation group (χ2 = 1.92, P = .16). Thus, participants were unable to guess their actual group beyond chance.

Discussion

In accordance with our primary hypothesis, active tDCS showed superior symptomatic improvement, based on HDRS-17 scores, compared with sham. This difference was associated with a medium effect size (NNT, 5.8; 95% CI, 3.3- 25.8).

Those who received tDCS significantly more frequently developed skin redness. The results also suggest that the frequency of itching and burning was higher in the active group. These AEs are often reported after active tDCS and seem to be caused by the injected current in the skin. Nonetheless, there were no losses due to these AEs, which were short-lived. Also, these AEs did not affect blinding.

Transcranial DCS was tolerable and safe, with both groups presenting similar TEAS rates, which is a concern when treating depression with tDCS. Such a feature is advantageous compared with other pharmacologic interventions presenting higher rates of TEAS and other AEs. No patient receiving antidepressant monotherapy presented affective switches during the trial.

Active tDCS was superior to sham for sustained response, but not for sustained remission. These outcomes measure different clinical concepts. Response aims to measure whether the intervention provides significant (although not necessarily complete) clinical relief of depressive symptoms, whereas, remission would reflect a category in which symptoms are minimal or absent. Both definitions are based on arbitrary thresholds and have received some criticism. Notwithstanding, only approximately half of responders are also remitters. Thus, our remission analyses might have been underpowered. Another possibility is that our tDCS protocol could not achieve remission. As tDCS effects per se are subtle, inducing small changes in the membrane potential, greater effects may be achieved when simultaneously combining tDCS with other treatments (eg, pharmacotherapy, other brain stimulation therapy, or psychotherapy). Therefore, different tDCS protocols, particularly combination therapies, could be explored in further studies.

BETTER was devised as an add-on tDCS trial in patients with BD, representative of a real-word setting, with a high prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders. Moreover, one-third of the enrolled patients presented a depressive episode after at least 2 adequate treatment regimens, 1 of them being a first-line treatment per CANMAT guidelines. Although there is no consensus on the definition of treatment-resistant BD, it is proposed that the concept should capture the “resistance” to the next treatment step, which is in line with the operationalization that we adopted. Furthermore, most patients were receiving antidepressant drugs as an adjuvant treatment to mood stabilizers. Although not recommended by guidelines, antidepressants are widely used for BD.

Other studies evaluating tDCS efficacy in BD are limited by their open-label design and/or mixed unipolar-bipolar sample. A meta-analysis evaluating tDCS efficacy in BD showed that tDCS effected a moderate to large depression improvement, as observed in our study. Moreover, our clinical efficacy was similar to that observed in repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and tDCS unipolar depression trials.

Limitations

The first limitation of the trial is that active tDCS was not superior to sham for CGI scale scores. This scale might not have been sensitive for our sample, composed of outpatients who were not severely ill. In addition, the CGI scale lacks precision and anchor points, making generalization between physicians and researchers difficult. We could not use an “improved” CGI scale, which presents additional information and is helpful to grade patients in the moderate severity range, as it has not been validated in Portuguese. Second, even using proper randomization techniques, there were imbalances in the random distribution of some baseline variables owing to small sample size.

Conclusions

Transcranial direct current stimulation was an effective and tolerable add-on treatment in this subsample of patients with type I or II bipolar disorder who were in a major depressive episode, with similar rates of treatment-emergent affective switches compared with sham. Although preliminary, our results are promising and encourage further trials to examine the efficacy of tDCS in a large bipolar disorder sample.

Trial Protocol

eTable. Mood Scores Over Time

References

- 1.Ferrari AJ, Stockings E, Khoo JP, et al. . The prevalence and burden of bipolar disorder: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(5):440-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. . The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Correll CU, Detraux J, De Lepeleire J, De Hert M. Effects of antipsychotics, antidepressants and mood stabilizers on risk for physical diseases in people with schizophrenia, depression and bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):119-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoeyen HK, Kessler U, Andreassen OA, et al. . Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a randomized controlled trial of electroconvulsive therapy versus algorithm-based pharmacological treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunoni AR, Chaimani A, Moffa AH, et al. . Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the acute treatment of major depressive episodes: a systematic review with network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(2):143-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavares DF, Myczkowski ML, Alberto RL, et al. . Treatment of bipolar depression with deep TMS (dTMS): results from a double-blind, randomized, parallel group, sham-controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(13):2593-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGirr A, Karmani S, Arsappa R, et al. . Clinical efficacy and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in acute bipolar depression. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(1):85-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayberg HS, Brannan SK, Tekell JL, et al. . Regional metabolic effects of fluoxetine in major depression: serial changes and relationship to clinical response. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(8):830-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser RH, Andrews-Hanna JR, Wager TD, Pizzagalli DA. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):603-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noda Y, Silverstein WK, Barr MS, et al. . Neurobiological mechanisms of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in depression: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2015;45(16):3411-3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo MF, Chen PS, Nitsche MA. The application of tDCS for the treatment of psychiatric diseases. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(2):146-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yavari F, Jamil A, Mosayebi Samani M, Vidor LP, Nitsche MA. Basic and functional effects of transcranial electrical stimulation (tES)-an introduction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;S0149-7634(17)30092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalu UG, Sexton CE, Loo CK, Ebmeier KP. Transcranial direct current stimulation in the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1791-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunoni AR, Moffa AH, Fregni F, et al. . Transcranial direct current stimulation for acute major depressive episodes: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(6):522-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loo CK, Alonzo A, Martin D, Mitchell PB, Galvez V, Sachdev P. Transcranial direct current stimulation for depression: 3-week, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(1):52-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunoni AR, Valiengo L, Baccaro A, et al. . The sertraline vs. electrical current therapy for treating depression clinical study: results from a factorial, randomized, controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(4):383-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunoni AR, Moffa AH, Sampaio-Junior B, et al. ; ELECT-TDCS Investigators . Trial of electrical direct-current therapy versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(26):2523-2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira Junior BdeS, Tortella G, Lafer B, et al. . The bipolar depression electrical treatment trial (BETTER): design, rationale, and objectives of a randomized, sham-controlled trial and data from the pilot study phase. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:684025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P; CONSORT Group . Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amorim P. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): validation of a short structured diagnostic psychiatric interview. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2000;22(3):106-115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. . Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(1):1-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seibt O, Brunoni AR, Huang Y, Bikson M. The pursuit of DLPFC: non-neuronavigated methods to target the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex with symmetric bicephalic transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):590-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanão TA, Moffa AH, Shiozawa P, Lotufo PA, Benseñor IM, Brunoni AR. Impact of two or less missing treatment sessions on tDCS clinical efficacy: results from a factorial, randomized, controlled trial in major depression. Neuromodulation. 2014;17(8):737-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valiengo LC, Goulart AC, de Oliveira JF, Bensenor IM, Lotufo PA, Brunoni AR. Transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of post-stroke depression: results from a randomised, sham-controlled, double-blinded trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(2):170-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunoni AR, Amadera J, Berbel B, Volz MS, Rizzerio BG, Fregni F. A systematic review on reporting and assessment of adverse effects associated with transcranial direct current stimulation. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(8):1133-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amsterdam JD, Shults J. Efficacy and mood conversion rate of short-term fluoxetine monotherapy of bipolar II major depressive episode. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):306-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rouder JN, Morey RD, Speckman PL, Province JM. Default Bayes factors for ANOVA designs. J Math Psychol. 2012;56(5):356-374. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):990-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preti A. How to calculate the number needed to treat (NNT) from Cohen's d or Hedges' g. https://rpubs.com/RatherBit/78905. Published May 2, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2017.

- 32.Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1492-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sienaert P, Lambrichts L, Dols A, De Fruyt J. Evidence-based treatment strategies for treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(1):61-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guarienti F, Caumo W, Shiozawa P, et al. . Reducing transcranial direct current stimulation-induced erythema with skin pretreatment: considerations for sham-controlled clinical trials. Neuromodulation. 2015;18(4):261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aparício LV, Guarienti F, Razza LB, Carvalho AF, Fregni F, Brunoni AR. A systematic review on the acceptability and tolerability of transcranial direct current stimulation treatment in neuropsychiatry trials. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(5):671-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunoni AR, Moffa AH, Sampaio-Junior B, Galvez A, Loo C. Treatment-emergent mania/hypomania during antidepressant treatment with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2017;10(2):260-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor DM, Cornelius V, Smith L, Young AH. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of drug treatments for bipolar depression: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(6):452-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nierenberg AA, DeCecco LM. Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):5-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naudet F, Millet B, Michel Reymann J, Falissard B. The fallacy of thresholds used in defining response and remission in depression rating scales. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(4):469-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. . Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1711-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vázquez GH, Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L. Co-occurrence of anxiety and bipolar disorders: clinical and therapeutic overview. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(3):196-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. . The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(11):1249-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baldessarini RJ, Leahy L, Arcona S, Gause D, Zhang W, Hennen J. Patterns of psychotropic drug prescription for US patients with diagnoses of bipolar disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(1):85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brunoni AR, Ferrucci R, Bortolomasi M, et al. . Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in unipolar vs bipolar depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(1):96-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunoni AR, Ferrucci R, Bortolomasi M, et al. . Interactions between transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and pharmacological interventions in the major depressive episode: findings from a naturalistic study. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(6):356-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palm U, Schiller C, Fintescu Z, et al. . Transcranial direct current stimulation in treatment resistant depression: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(3):242-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dondé C, Amad A, Nieto I, et al. . Transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) for bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;78:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kadouri A, Corruble E, Falissard B. The improved Clinical Global Impression Scale (iCGI): development and validation in depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice. Lancet. 2002;359(9305):515-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable. Mood Scores Over Time