This case-cohort study uses data from the dal-Outcomes randomized clinical trial to determine the association of lipoprotein(a) level with the risk for cardiovascular events following acute coronary syndrome.

Key Points

Question

For patients with recent acute coronary syndrome, is the concentration of lipoprotein(a) associated with the subsequent risk of major ischemic cardiovascular events?

Findings

This case-cohort analysis of 969 cases and 3170 controls participating in the dal-Outcomes randomized clinical trial found that the concentration of lipoprotein(a) measured 4 to 12 weeks after acute coronary syndrome had no association with the risk of death due to coronary heart disease, major nonfatal coronary events, or stroke.

Meaning

This finding calls into question whether treatment to reduce lipoprotein(a) levels will thereby reduce the risk of ischemic cardiovascular events after acute coronary syndrome.

Abstract

Importance

It is uncertain whether lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], which is associated with incident cardiovascular disease, is an independent risk factor for recurrent cardiovascular events after acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Objective

To determine the association of Lp(a) concentration measured after ACS with the subsequent risk of ischemic cardiovascular events.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nested case-cohort analysis was performed as an ad hoc analysis of the dal-Outcomes randomized clinical trial. This trial compared dalcetrapib, the cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor, with placebo in patients with recent ACS and was performed between April 2008 and September 2012 at 935 sites in 27 countries. There were 969 case patients who experienced a primary cardiovascular outcome, and there were 3170 control patients who were event free at the time of a case event and had the same type of index ACS (unstable angina or myocardial infarction) as that of the respective case patients. Concentration of Lp(a) was measured by immunoturbidimetric assay. Data analysis for this present study was conducted from June 8, 2016, to April 21, 2017.

Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned to receive treatment with dalcetrapib, 600 mg daily, or matching placebo, beginning 4 to 12 weeks after ACS.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Death due to coronary heart disease, a major nonfatal coronary event (myocardial infarction, hospitalization for unstable angina, or resuscitated cardiac arrest), or fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke.

Results

The mean (SD) age was 63 (10) years for the 969 case patients and 60 (9) years for the 3170 control patients, and both cohorts were composed of predominantly male (770 case patients [79%] and 2558 control patients [81%]; P = .40) and white patients (858 case patients [89%] and 2825 control patients [89%]; P = .62). At baseline, the median (interquartile range) Lp(a) level was 12.3 (4.7-50.9) mg/dL. There was broad application of evidence-based secondary prevention strategies after ACS, including use of statins in 4030 patients (97%). The cumulative distribution of baseline Lp(a) levels did not differ between cases and controls at P = .16. Case-cohort regression analysis showed no association of baseline Lp(a) level with risk of cardiovascular events. For a doubling of Lp(a) concentration, the hazard ratio (case to control) was 1.01 (95% CI, 0.96-1.06; P = .66) after adjustment for 16 baseline variables, including assigned study treatment.

Conclusions and Relevance

For patients with recent ACS who are treated with statins, Lp(a) concentration was not associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. These findings call into question whether treatment specifically targeted to reduce Lp(a) levels would thereby lower the risk for ischemic cardiovascular events after ACS.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00658515

Introduction

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], a particle containing apolipoprotein B100 and apolipoprotein (a), may promote atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and consequent cardiovascular events. Epidemiological and genetic data suggest that a high level of Lp(a) is an independent risk factor for incident cardiovascular disease. For patients with established stable coronary heart disease, an association of Lp(a) with cardiovascular risk has been inconsistent, and it has been suggested that such an association may depend on a concurrent high concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C).

Patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are at high risk for recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events, despite high-intensity statin treatment and other secondary prevention strategies. It is uncertain whether Lp(a) is an independent risk factor for further cardiovascular events after ACS, particularly when LDL-C is controlled. In addition, Lp(a) is a positive acute-phase reactant with increased concentration for several weeks following ACS. Therefore, the predictive value of Lp(a) after ACS may be more reliably determined after a period of clinical stabilization.

If residual cardiovascular risk after ACS were associated with levels of Lp(a), the findings might suggest Lp(a) as an additional target of therapy. This possibility assumes additional relevance in light of new treatments that reduce levels of Lp(a) substantially, including PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) antibodies and antisense oligonucleotide to apolipoprotein (a). This nested case-cohort analysis used data from the dal-Outcomes randomized clinical trial to determine whether Lp(a) concentration is associated with the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events following ACS.

Methods

Study Population

This study was an ad hoc analysis of the dal-Outcomes trial, a randomized, double-blind comparison of dalcetrapib, a cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor, to placebo in 15 871 patients with recent ACS. Trial design and principal results have been described previously. The trial was performed between April 2008 and September 2012 at 935 sites in 27 countries. The institutional review board of each site approved the trial, and all participants provided informed consent. Data analysis for the present study was conducted from June 8, 2016, to April 21, 2017.

Qualifying patients were randomly assigned to receive dalcetrapib, 600 mg daily, or matching placebo, beginning 4 to 12 weeks after an index ACS event, when they were clinically stable and had completed all planned coronary revascularization procedures. Exclusion criteria included New York Heart Association class III or IV symptoms of heart failure or class II symptoms if the left ventricular ejection fraction was found to be 40% or less, uncontrolled hypertension, a serum creatinine level higher than 2.2 mg/dL (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4), or a triglyceride level higher than 400 mg/dL (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113). Evidence-based treatments, including statins, were encouraged for all patients.

Measurement of Lp(a)

The level of Lp(a) was measured in serum samples at baseline (randomization visit) and at 3 months of assigned treatment by immunoturbidimetric assay (Cobas; Roche Diagnostics) with an operating range of 3 to 100 mg/dL (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0357), an intra-assay coefficient of variation of 0.5% to 1.3%, and an interassay coefficient of variation of 1.2% to 1.7%.

Nested Case-Cohort Design

The dal-Outcomes trial included a nested case-cohort study to evaluate the association between baseline levels of circulating biomarkers and the risk of a subsequent primary end-point event, defined as death due to coronary heart disease, a major nonfatal coronary event (myocardial infarction [MI], hospitalization for unstable angina, or resuscitated cardiac arrest), or a fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke. These events were adjudicated by a blinded, independent event adjudication committee.

The analysis data set included 4139 individuals. Case patients (n = 969) were patients with a baseline measurement of Lp(a) who experienced a primary end-point event. Control patients (n = 3170) for each case patient were randomly selected from patients who were event free at the time of a case event and who had the same type of index ACS (unstable angina or MI) as that of the respective case patients.

Case-cohort regression was used to infer an association between Lp(a) levels and the hazard of an end-point event. The analysis included 1146 primary end-point events (969 among case patients and 177 among control patients). The 177 events among the control patients occurred after their matched case event time. Analyses used log2 Lp(a) to remove the positive skew in the distribution of Lp(a) levels. Results are reported as the hazard ratio (HR) for a primary end-point event for each doubling of baseline Lp(a) level, with the corresponding 95% CI and 2-sided P value.

Adjusted analyses included as covariates 16 baseline demographic, medical history, laboratory, and treatment variables, as indicated in the Table. The cumulative distribution of Lp(a) was compared in case patients and control patients using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Results are reported as 95% CIs and 2-sided P values, with 2-sided P < .05 considered statistically significant.

Table. Baseline Characteristics of Case Patients and Control Patients and the Association of Baseline Characteristics With Lp(a) Level.

| Characteristic | Cases (n = 969) |

Controls (n = 3170) |

P Value (Cases vs Controls) |

Regression Coefficienta |

P Value (Regression Coefficient)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63 (10) | 60 (9) | <.001 | 0.996 | .09 |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 770 (79) | 2558 (81) | .40 | 0.766 | <.001 |

| White race, No. (%) | 858 (89) | 2825 (89) | .62 | 0.867 | .02 |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | 765 (79) | 2137 (67) | <.001 | 0.962 | .35 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 355 (37) | 735 (23) | <.001 | 0.887 | <.01 |

| Current smoking, No. (%) | 205 (21) | 616 (19) | .24 | 0.918 | .08 |

| Prior MI, No. (%) | 316 (33) | 482 (15) | <.001 | 1.153 | <.01 |

| Prior PCI or CABG, No. (%) | 364 (38) | 542 (17) | <.001 | 1.148 | <.01 |

| Prior stroke, No. (%) | 65 (7) | 101 (3) | <.001 | 1.002 | .99 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29 (5) | 29 (5) | .07 | 0.991 | .03 |

| LDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 80.9 (30.9) | 75.3 (24.7) | <.001 | 1.009 | <.001 |

| HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 42.5 (12.0) | 42.2 (11.2) | .49 | 1.003 | .06 |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dL | 141 (73) | 131 (69) | <.001 | 0.999 | <.01 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD), % | 6.3 (1.1) | 6.0 (0.8) | <.001 | 0.958 | .04 |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.7 m2 | 78 (21) | 82 (18) | <.001 | 0.996 | <.001 |

| Treatment with dalcetrapib, No. (%) | 493 (51) | 1573 (50) | .49 | 0.980 | .60 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

SI conversion factors: To convert LDL-C and HDL-C to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113; and to convert hemoglobin A1c to the proportion of total hemoglobin, multiply by 0.01.

The regression coefficient for association of a characteristic with Lp(a) level is the relative change in Lp(a) associated with a 1-unit increase in continuous characteristics or the presence of dichotomous characteristics.

Results

At baseline, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) Lp(a) level was 12.3 (4.7-50.9) mg/dL. The median (IQR) follow-up time for study participants was 29 (24-34) months. There was high use of contemporary secondary prevention strategies, including statins (4030 [97%]), β-blockers (3614 [87%]), angiotensin-converting enzyme or receptor inhibitors (3323 [80%]), aspirin (4019 [97%]), clopidogrel bisulfate or other platelet P2Y12 antagonists (3675 [89%]), and coronary revascularization for the index ACS event (3668 [89%]).

The Table shows the baseline characteristics of case patients and control patients and the association of baseline characteristics with Lp(a) concentration. The mean (SD) age was 63 (10) years for the case patients and 60 (9) years for the control patients, and both case and control patients were predominantly male (770 [79%] and 2558 [81%]; P = .40) and white (858 [89%] and 2825 [89%]; P = .62). In addition, case patients were more likely to have a history of hypertension, diabetes, prior MI, coronary revascularization, or stroke; higher levels of LDL-C, triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c; and a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate. Lipoprotein (a) concentration was positively associated with prior MI or coronary revascularization and the level of LDL-C. It was negatively associated with male sex, diabetes, and levels of triglycerides, and the estimated glomerular filtration rate. Approximately 50% of case patients and 50% of control patients were treated with dalcetrapib, a finding consistent with the neutral effect of dalcetrapib in the main analysis of the trial.

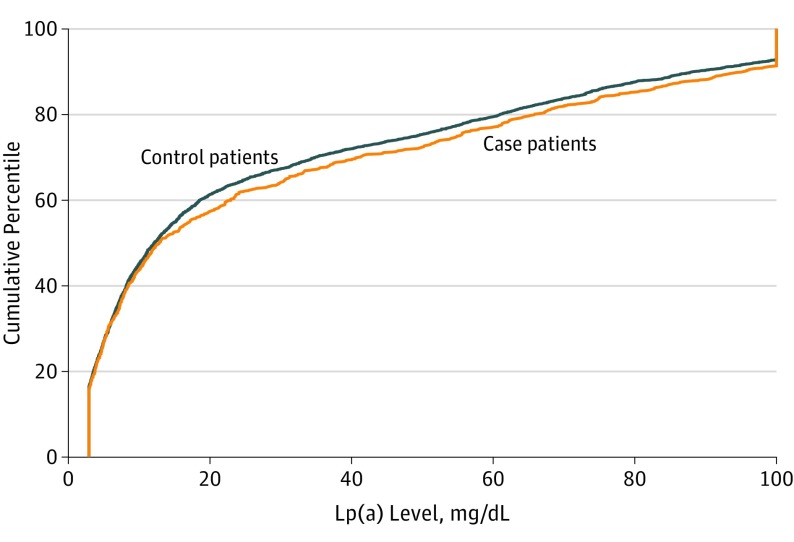

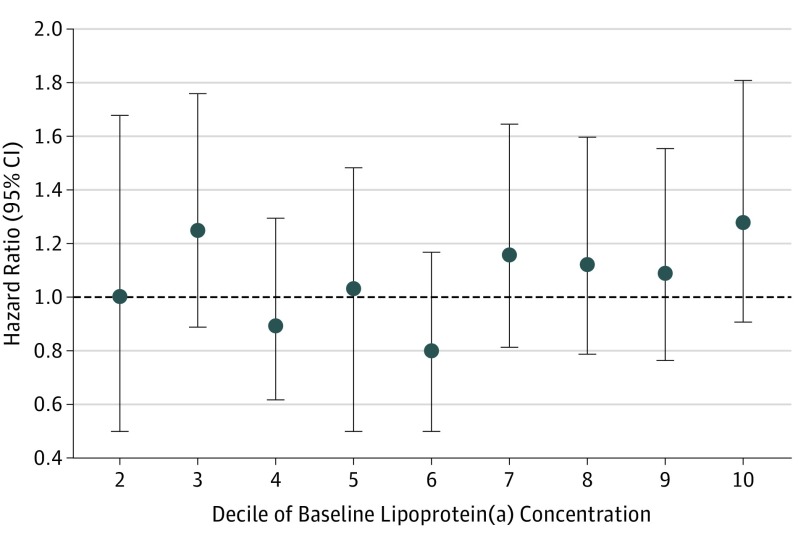

Median (IQR) concentration of Lp(a) was 12.9 (4.7-55) mg/dL in case patients and 12.1 (4.6-49) mg/dL in control patients. Figure 1 shows that the cumulative distribution of Lp(a) did not differ between case patients and control patients at P = .16. The HR (case to control) for a doubling of baseline Lp(a) level was 1.03 (95% CI, 0.98-1.08; P = .21) in unadjusted analysis and 1.01 (95% CI, 0.96-1.06; P = .66) in adjusted analysis. To determine if an association between Lp(a) and cardiovascular risk was evident at higher levels of Lp(a), we examined HRs by decile of baseline Lp(a) level (Figure 2). Again, no significant association was evident, even in the highest deciles. Finally, Lp(a) was dichotomized at 50 mg/dL. The resulting HR (≥50/<50 mg/dL) of 1.16 (95% CI, 0.97-1.39; P = .11) does not indicate a significant association of higher levels of Lp(a) with cardiovascular risk.

Figure 1. Cumulative Distribution of Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] in Case Patients and Control Patients.

Because the operating range for the Lp(a) assay was 3 to 100 mg/dL (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0357), any concentration of 100 mg/dL or higher is indicated at 100 mg/dL. The cumulative distribution of Lp(a) did not differ between case patients and control patients at P = .16, as determined by the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Figure 2. Hazard Ratio by Decile of Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)].

Filled circles and vertical lines indicate the hazard ratio and 95% CI for deciles 2 to 10 of Lp(a), relative to decile 1 [Lp(a) <2.9 mg/dL]. The decile ranges for deciles 2 to 10 of Lp(a) are 2.9 to less than 3.6 mg/dL (decile 2), 3.6 to less than 5.7 mg/dL (decile 3), 5.7 to less than 8.3 mg/dL (decile 4), 8.3 to less than 12 mg/dL (decile 5), 12 to less than 20 mg/dL (decile 6), 20 to less than 37 mg/dL (decile 7), 37 to less than 62 mg/dL (decile 8), 62 to less than 91 mg/dL (decile 9), and 91 to greater than 100 mg/dL (decile 10). To convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0357.

At 3 months of assigned treatment, there were small decreases in the concentration of Lp(a) among patients treated with dalcetrapib (mean [SD] change from baseline, −1.7 [6.6] mg/dL [n = 1717]; P < .001) and among patients treated with placebo (−0.6 [6.2] mg/dL [n = 1760]; P < .001). The change from baseline was greater with dalcetrapib than with placebo (P < .001).

Discussion

Although Lp(a) levels appear to be associated with cardiovascular risk in initially healthy individuals, the present analysis indicates that there is no association between Lp(a) level and risk of ischemic cardiovascular events after ACS. Our neutral results are consistent with the findings from the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) trial, the Prevention of Events with Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibition (PEACE) trial, the Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health (LURIC) observational study of patients with prior MI or stable coronary heart disease as well as the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy (PROVE-IT) trial of patients with ACS. The results are also consistent with those of an analysis of the Effect of Rosuvastatin Versus Atorvastatin (SATURN) trial, in which Lp(a) level was not associated with progression or regression of coronary atheroma volume assessed by intravascular ultrasonography.

However, findings from the present analysis contrast with those from the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome With Low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcomes (AIM-HIGH) trial of patients with established, chronic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, as well as the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) of patients with coronary heart disease and pronounced elevation of serum cholesterol levels. In these studies, significant associations were found between Lp(a) level and major adverse cardiovascular events (AIM-HIGH trial) or between Lp(a) level and death (4S).

The disparate findings among these studies are not readily reconciled and are unlikely to be explained by differences in baseline Lp(a) levels (median range, 5-17 mg/dL in the previous studies vs 13 mg/dL in the present analysis), baseline LDL-C levels (nearly identical in the AIM-HIGH trial and the present analysis, with a mean level of approximately 75 mg/dL), or duration of follow-up (2 to 10 years in the neutral analyses vs 3 to 5 years in the positive analyses).

In studies that specifically evaluated patients with ACS, the congruent neutral findings from the PROVE-IT trial and the present analysis suggest that prognosis is dominated by factors other than Lp(a) concentration or that any influence of Lp(a) level is nullified by the prevalent use of high-intensity statin therapy, dual antiplatelet therapy, and coronary revascularization procedures. Moreover, the corresponding findings from the PROVE-IT trial (with Lp[a] levels measured approximately 1 week after ACS) and from the present analysis (with the Lp[a] level measured 4 to 12 weeks after ACS) suggest that acute-phase effects on Lp(a) levels are unlikely to influence any association of Lp(a) level with cardiovascular outcomes; instead, the composite of the data on ACS indicate that no such association exists.

Despite other evidence that Lp(a) promotes the progression of atherosclerosis and increases the risk of thrombosis in individuals with high plaque burden, data from the present analysis indicate that the concentration of Lp(a) does not predict the risk of ischemic cardiovascular events in patients with recent ACS. No threshold effect was apparent. Nonetheless, it remains to be determined whether a reduction in Lp(a) concentration with new therapies, such as PCSK9 inhibitors or antisense oligonucleotide targeting apolipoprotein (a), will thereby result in reduced risk of ischemic cardiovascular events after ACS.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this analysis include a large number of cardiovascular end points, the broad use of contemporary secondary prevention therapies, and ascertainment of Lp(a) after any acute-phase effects on its levels. Its limitations include the possibility that the analysis was underpowered to detect an association of Lp(a) level with cardiovascular outcomes restricted to the upper range of Lp(a) concentrations. Other limitations are those inherent to case-cohort studies, which are subject to confounding because only a subset of the entire trial cohort had biomarker measurements. Matching and covariate adjustments were used to account for the most likely confounders, but potential confounding by other unmeasured covariates cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

Although Lp(a) is believed to be an atherogenic lipoprotein, the present analysis indicates that Lp(a) concentration does not predict the risk of ischemic cardiovascular events following ACS among patients who receive current evidence-based therapies.

References

- 1.Tsimikas S. A test in context: lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(6):692-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emdin CA, Khera AV, Natarajan P, et al. ; CHARGE–Heart Failure Consortium; CARDIoGRAM Exome Consortium . Phenotypic characterization of genetically lowered human lipoprotein(a) levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(25):2761-2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Perry PL, et al. ; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration . Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 2009;302(4):412-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Donoghue ML, Morrow DA, Tsimikas S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) for risk assessment in patients with established coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(6):520-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai A, Li L, Zhang Y, et al. Baseline LDL-C and Lp(a) elevations portend a high risk of coronary revascularization in patients after stent placement. Dis Markers. 2013;35(6):857-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honda Y, Oshima S, Ogawa H, et al. Plasma lipoprotein (a) levels and fibrinolytic activity in acute myocardial infarction. Jpn Circ J. 1994;58(12):869-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda S, Abe A, Seishima M, Makino K, Noma A, Kawade M. Transient changes of serum lipoprotein(a) as an acute phase protein. Atherosclerosis. 1989;78(2-3):145-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raal FJ, Giugliano RP, Sabatine MS, et al. Reduction in lipoprotein(a) with PCSK9 monoclonal antibody evolocumab (AMG 145): a pooled analysis of more than 1,300 patients in 4 phase II trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(13):1278-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viney NJ, van Capelleveen JC, Geary RS, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting apolipoprotein(a) in people with raised lipoprotein(a): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trials. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2239-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, et al. ; dal-OUTCOMES Investigators . Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(22):2089-2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ballantyne CM, et al. ; dal-OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators . Rationale and design of the dal-OUTCOMES trial: efficacy and safety of dalcetrapib in patients with recent acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2009;158(6):896-901.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zewinger S, Kleber ME, Tragante V, et al. ; GENIUS-CHD consortium . Relations between lipoprotein(a) concentrations, LPA genetic variants, and the risk of mortality in patients with established coronary heart disease: a molecular and genetic association study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(7):534-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puri R, Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and coronary atheroma progression rates during long-term high-intensity statin therapy: Insights from SATURN. Atherosclerosis. 2017;263:137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albers JJ, Slee A, O’Brien KD, et al. Relationship of apolipoproteins A-1 and B, and lipoprotein(a) to cardiovascular outcomes: the AIM-HIGH trial (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglyceride and Impact on Global Health Outcomes). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(17):1575-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg K, Dahlén G, Christophersen B, Cook T, Kjekshus J, Pedersen T. Lp(a) lipoprotein level predicts survival and major coronary events in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Clin Genet. 1997;52(5):254-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]