Abstract

Introduction

The weekend effect is a perceived difference in outcome between medical care provided at the weekend when compared to that of a weekday. Clearly multifactorial, this effect remains incompletely understood and variable in different clinical contexts. In this study we analyse factors relevant to the weekend effect in elective lower-limb joint replacement at a large NHS multispecialty academic healthcare centre.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the electronic medical records of 352 consecutive patients who received an elective primary hip or knee arthroplasty. Patient, clinical and time-related variables were extracted from the records. The data were anonymised, then processed using a combination of uni- and multivariate statistics.

Results

There is a significant association between the selected weekend effect outcome measure (postoperative length of stay) and patient age, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, time to first postoperative physiotherapy and time to postoperative radiography but not day of the week of operation.

Discussion

We were not able to demonstrate a weekend effect in elective lower-limb joint replacement at our institution nor identify a factor that would require additional weekend clinical medical staffing. Rather, resource priorities would seem to include measures to optimise at-risk patients preoperatively and measures to reduce time to physiotherapy and radiography postoperatively.

Conclusions

Our findings imply that postoperative length of stay could be minimised by strategies relating to patient selection and access to postoperative services. We have also identified a powerful statistical methodology that could be applied to other service evaluations in different clinical contexts.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Elective surgical procedures, Length of stay, Postoperative care, Preoperative care

Introduction

The weekend effect, which is defined as a deferred increase in patient mortality associated with weekend compared to weekday admission,1 or weekend compared with weekday operation, in elective surgery,2,3 has been described in both emergency and elective surgical settings in the NHS.2,4,5 Levels of staffing, both clinical and allied health staff, and case mix have been identified as potential factors, although the mechanisms of the weekend effect have yet to be satisfactorily established.1 Trust-level data suggest that the weekend effect is subject to considerable national variation. Recently, the High-intensity Specialist Led Acute Care Collaborative compared the mortality odds ratios for weekend to weekday acute admissions of 115 NHS trusts in England. They reported ratios ranging from 0.81 to 1.35 and noted that 83% of trusts possessed an odds ratio greater than 1.6 By definition, 17% of trusts therefore possessed an odds ratio of less than or equal to 1. Variations in the weekend effect have also been observed across specialties, between elective and emergency admissions and according to procedure.2,7 For example, Aylin et al. observed the presence of a weekend effect in major gastrointestinal surgery, lung excision and coronary artery bypass grafting but not in abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, varicose vein surgery, tonsillectomy, hip and knee arthroplasty and hernia repair. Our aim was therefore to measure several relevant potential factors relating to the weekend effect in a specific clinical setting and to apply and develop statistical analyses of these factors. We further aimed to understand these factors in terms of weekend staffing requirements.

We examined patient outcomes and possible contributing factors, including weekday compared with weekend care, in 352 elective orthopaedic patients who received a primary hip or knee arthroplasty at a large NHS multispecialty academic healthcare centre (Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust). The elective service benefits from weekend allied health service provision, ring-fenced beds, surgical lists six days a week (Monday to Saturday) and consultant-led weekend care.

One of the difficulties of comparing weekday and weekend patient care in this study is that the weekend effect outcome, namely 30-day mortality, has a low incidence in elective orthopaedics (0.22% for primary knee and 0.27% for primary hip arthroplasties nationally).8 A study powered to observe changes in this parameter would require a large sample size. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, an alternative primary outcome measure (postoperative length of stay) was used. Postoperative length of stay, which is considered a ‘weekend effect phenomenon’,9 has been shown to increase for cases undertaken towards the end of the week and decreases following interventions to improve weekend care.10

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the electronic medical records (EPIC Systems Corporation, Verona, USA), crossmatched against National Joint Registry submission data, of all patients who received a primary hip or knee arthroplasty, between 1 April and 23 August 2016 at Cambridge University Hospitals and retrospectively assessed postoperative length of stay, defined here as time to hospital discharge following cessation of intraoperative anaesthesia. The service evaluation protocol was approved by the Clinical Audit Committee at Cambridge University Hospitals.

Patient variables (date of birth, body mass index and American Society of Anesthesiologists, ASA, physical status classification), clinical variables (case type, lead consultant, operating surgeon grade, indication, intraoperative events and anaesthetic type) and time-related variables (month of operation, day of the week of operation and times and dates of cessation of intraoperative anaesthesia, postoperative radiography, first postoperative physiotherapy and hospital discharge) were extracted from the records. The postoperative period was taken to commence at the time of cessation of intraoperative anaesthesia. Patient age at operation and times to postoperative radiography, first postoperative physiotherapy and hospital discharge were calculated from the extracted data.

Patients were excluded in cases where the indication for their operation was trauma; that is, non-elective (17 patients) and where the time to discharge could not be established (1 patient, who died before discharge). Overall, 352 patients (170 primary hip and 182 primary knee arthroplasties) were included in the analysis.

Anonymised data were processed using a combination of multi- and univariate statistics. Mixed quantitative and qualitative data were imported into SIMCA-P 13.0 (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) and analysed using partial least squares (PLS) regression, with postoperative length of stay set as the response variable, Y. Missing data were interpolated, using a least squares fit, but were assigned no influence on the model. Response permutation testing (n = 100) and analysis of variance of the cross-validated residuals (CV-ANOVA) were used to validate the model. Based on the results of the multivariate analysis, selected data were imported into Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, USA) for univariate analysis. Data were checked for normality using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Non-normally distributed data were analysed using a combination of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and the Kruskal–Wallis H test (one-way ANOVA on ranks) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

Results

Case mix, study population demographics and postoperative length of stay were stratified by day of the week of operation and compared (Table 1). Over the 21 Mondays, Tuesdays, Fridays and Saturdays and 20 Wednesdays and Thursdays included in the study period, a similar number of cases were performed on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. Considerably fewer cases were performed on Wednesdays and Saturdays and considerably more cases performed on Fridays. These differences are largely attributable to the number of cases performed per day, rather than the number of times a given day of the week occurred within the study period. The ratio of elective primary hip to knee arthroplasties ranged from 0.59 to 1.36. Overall, there were more female than male cases (220 vs. 132). Only on Thursdays were there more male than female cases. There were no differences between operations performed on different days of the week in terms of patient age and body mass index, and ASA II was the most frequent patient physical status classification on all days of the week. Postoperative length of stay was unaffected by day of the week of operation.

Table 1.

Study population demographic features

| Demographic feature | Day of the week of operation | |||||

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | |

| Primary arthroplasty | 60 | 59 | 26 | 70 | 111 | 26 |

| Hip | 26 | 22 | 15 | 32 | 62 | 13 |

| Knee | 34 | 37 | 11 | 38 | 49 | 13 |

| Hip : knee ratio | 0.76 | 0.59 | 1.36 | 0.84 | 1.27 | 1 |

| Male : female ratio | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 1.06 | 0.44 | 0.73 |

| Age (years)a | 72 (66–78) | 69 (60–76) | 67 (50–77) | 70 (63–77) | 70 (63–77) | 66 (57–77) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)b | 31 (27.1–34.7) | 30.1 (26.8–37.2) | 26.6 (24.4–33.3) | 29.2 (26.4–35.7) | 29 (25.3–35.6) | 31.2 (26.4–35) |

| ASA classificationc | II | II | II | II | II | II |

| Postoperative length of stay (hours)d | 73 (51–100) | 70 (53–103) | 72 (46–120) | 73 (53–99) | 75 (54–99) | 72 (51–82) |

a Median age in years (interquartile range) 2 significant figures (sf).

b Median body mass index: weight (kg)/height (m2) (interquartile range) 3 sf.

c Mode American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification (I–IV).

d Median postoperative length of stay (interquartile range) 2 sf.

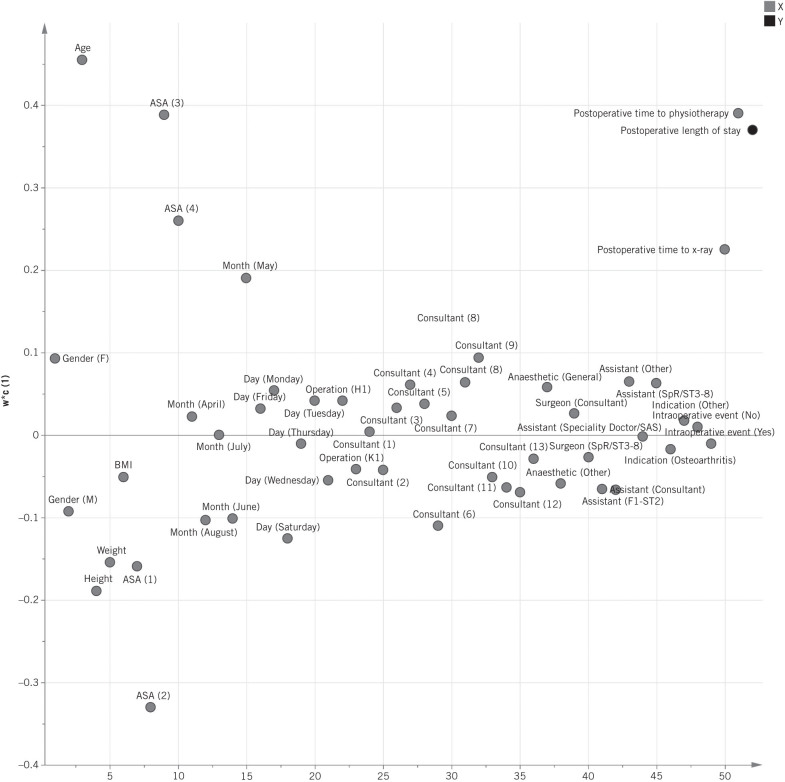

Given that postoperative length of stay was unaffected by day of the week of operation, the relationships between other variables and postoperative length of stay were examined. A PLS model was built by regressing postoperative length of stay against the patient, clinical and time-related variables extracted from the records (1 latent variable from cross-validation; R2X = 3.94%, R2Y = 24.8%, Q2 = 14.4%; CV-ANOVA = 1.52 × 10 12). The loadings plot of the PLS model (Fig 1) demonstrates that increasing patient age, time to first postoperative physiotherapy, time to postoperative radiography and ASA classification are the most important correlates with increasing postoperative length of stay.

Figure 1.

Loadings plot of partial least squares model: correlations between study variables. The black circle represents the response variable, Y (postoperative length of stay) and the grey circles represent the X variables. The position of the X variables on the y-axis (w*c[1]) gives information about the sign and strength of their correlation with the Y variable. In this figure, the more positive the y-axis position of the X variables, the greater their positive correlation with postoperative length of stay. The more negative the y-axis position of the X variables, the greater their negative correlation with postoperative length of stay (n = 352).

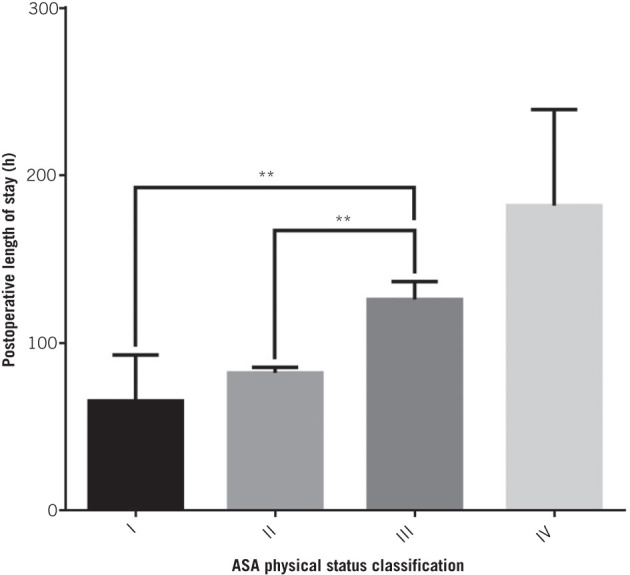

Univariate analysis was performed to confirm the findings of the multivariate analysis. Significant positive correlations were observed between postoperative length of stay and age (Spearman r = 0.33, 95% confidence interval, CI, 0.23–0.43; P < 0.0001), postoperative length of stay and time to first postoperative physiotherapy (Spearman r = 0.17, 95% CI 0.06–0.27, P = 0.0014) and postoperative length of stay and time to postoperative radiography (Spearman r = 0.17, 95% CI 0.07–0.28, P = 0.0011). To examine the relationship between ASA classification and postoperative length of stay, the Kruskal–Wallis H test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, were performed (Fig 2). Higher ASA classifications were associated with increased postoperative length of stay (ANOVA 0.0001; ASA I vs. III, P = 0.0073; ASA II vs. III, P = 0.0013).

Figure 2.

Postoperative length of stay stratified by ASA classification. Column heights represent median postoperative length of stay; bars represent interquartile range; stars indicate levels of significant difference, estimated by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. ** represent P-values between 0.01 and 0.001. ASA I (n = 48), ASA II (n = 206), ASA III (n = 91), ASA IV (n = 7).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that postoperative length of stay is unaffected by day of the week of operation and suggest that elective orthopaedic care at Cambridge University Hospitals is not subject to the weekend effect. We did not therefore identify a requirement for increased weekend clinical medical staff in this setting. These findings are consistent with and extend those of Pakzad et al., who reported no association between length of stay and day of the week of operation in elective ankle surgery for end-stage ankle arthritis, at their institution.11

The results also show a significant association between increasing postoperative length of stay and increasing age and ASA classification in elective primary hip and knee arthroplasties, an effect also observed by Pakzad et al. 11 in elective ankle surgeries and Collins et al.12 across major elective orthopaedic, vascular, urological and general surgeries. We therefore support the conclusions of Fitz-Henry et al.13 and advocate that older, ASA III and IV, elective orthopaedic patients receive enhanced pre- and perioperative anaesthetic input to optimise their physical condition.

Lastly, the results show that increasing postoperative length of stay is significantly associated with increasing time to first postoperative physiotherapy and postoperative radiography, which are standard steps in the orthopaedic postoperative protocol. Time to first postoperative physiotherapy is indicative of time to mobilisation, which has previously been associated with length of stay following elective orthopaedic surgery.14–16 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time an association between postoperative length of stay and time to postoperative radiography has been reported. The first postoperative physiotherapy and postoperative radiography represent important clinical bottlenecks in the orthopaedic postoperative protocol. However, these variables may simply be correlated, rather than causally associated with postoperative length of stay. We believe that interventions to reduce time to first postoperative physiotherapy and radiography warrant further investigation, to determine whether they reduce postoperative length of stay in an elective orthopaedic context.

One of the limitations of this study is that it does not explicitly control for case mix and study population demographic variables, which might confound the results and mask a weekend effect. However, those variables associated with postoperative length of stay (age and ASA classification) do not vary across the week, while those variables which do vary across the week (case mix and gender ratio) are not associated with postoperative length of stay and are therefore unlikely to confound the results.

Conclusion

Increasing age, ASA classification, time to postoperative radiography and time to first postoperative physiotherapy are significantly associated with increasing postoperative length of stay, while there is no evidence of a weekend effect in elective orthopaedic care at Cambridge University Hospitals. We did not identify a factor that would require additional weekend clinical medical staffing. These results support the local and national moves to increase multidisciplinary perioperative care and an effective enhanced recovery programme, which are already common locally and across much of UK orthopaedics. A focus on reducing time to first postoperative physiotherapy and radiography may further streamline existing enhanced recovery pathways. We have also identified a powerful statistical methodology that could be applied to other clinical settings and service evaluations.

References

- 1.Chen YF, Boyal A, Sutton E et al. The magnitude and mechanisms of the weekend effect in hospital admissions: a protocol for a mixed methods review incorporating a systematic review and framework synthesis. Syst Rev 2016; : 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aylin P, Alexandrescu R, Jen MH et al. Day of week of procedure and 30 day mortality for elective surgery: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics. BMJ 2013; : f2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. Elective, major noncardiac surgery on the weekend: a population-based cohort study of 30-day mortality. Med Care 2014;(6): 557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozdemir BA, Sinha S, Karthikesalingam A et al. Mortality of emergency general surgical patients and associations with hospital structures and processes. Br J Anaesth 2016; (1): 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLean RC, McCallum IJ, Dixon S et al. A 15-year retrospective analysis of the epidemiology and outcomes for elderly emergency general surgical admissions in the North East of England: a case for multidisciplinary geriatric input. Int J Surgery 2016; : 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aldridge C, Bion J, Boyal A et al. Weekend specialist intensity and admission mortality in acute hospital trusts in England: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2016; (10040): 178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohammed MA, Sidhu KS, Rudge G et al. Weekend admission to hospital has a higher risk of death in the elective setting than in the emergency setting: a retrospective database study of national health service hospitals in England. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; : 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briggs TW. Getting It Right First Time. Improving the Quality of Orthopaedic Care Within the National Health Service In England. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards PK, Hadden KB, Connelly JO et al. Effect of total joint arthroplasty surgical day of the week on length of stay and readmissions: a clinical pathway approach. J Arthroplasty 2016; : 2,726–2,729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blecker S, Goldfeld K, Park H et al. Impact of an intervention to improve weekend hospital care at an academic medical center: an observational study. J Gen Intern Med 2015; : 1,657–1,664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakzad H, Thevendran G, Penner MJ et al. Factors associated with longer length of hospital stay after primary elective ankle surgery for end-stage ankle arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; : 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins TC, Daley J, Henderson WH et al. Risk factors for prolonged length of stay after major elective surgery. Ann Surg 1999; : 251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitz-Henry J. The ASA classification and peri-operative risk. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2011; : 185–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raut S, Mertes SC, Muniz-Terrera G et al. Factors associated with prolonged length of stay following a total knee replacement in patients aged over 75. Int Orthop 2012; : 1,601–1,608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tayrose G, Newman D, Slover J et al. Rapid mobilization decreases length-of-stay in joint replacement patients. Bull Hosp Joint Dis 2013; : 222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wellman SS, Murphy AC, Gulcynski D et al. Implementation of an accelerated mobilization protocol following primary total hip arthroplasty: impact on length of stay and disposition. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2011; : 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]