Abstract

A 73-year-old man was referred for surgical excision of a massive mediastinal and cervical liposarcoma following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Surgery was performed via a cervical incision, sternotomy and right posterolateral thoracotomy. The tumour arose from the oesophagus, which underwent extensive dissection and was oversewn with pleura after tumour resection. Histology confirmed a completely excised grade 2 de-differentiated liposarcoma with complete macroscopic excision. The patient made an excellent recovery. Oesophageal liposarcomas are rare and, unlike in this case, often extend intraluminally, necessitating oesophagectomy. To our knowledge, this is the largest such tumour found in the literature.

Keywords: Liposarcoma, Oesophageal, Mediastinal

Introduction

Liposarcomas originate from adipose tissue.1 Their response to chemotherapy is variable and surgery is the mainstay of treatment.1,2 Primary mediastinal liposarcomas are very rare, accounting for less than 1% of all mediastinal tumours.1,3 They tend to be large before diagnosis and generally present with symptoms related to compression or invasion of intrathoracic structures.

Case report

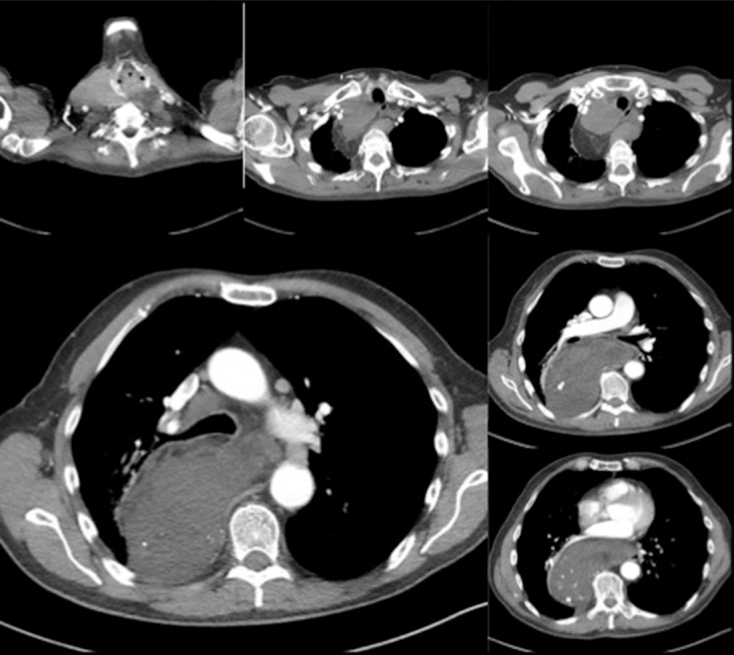

A 73-year-old man was referred for excision of a massive, biopsy-proven, mediastinal liposarcoma. He had no significant past medical history and had initially presented to primary care with a neck lump. Investigations revealed a large mediastinal mass extending from the angle of the mandible to the oesophageal hiatus (Fig 1, 2 and supplementary images and videos). On computed tomography (CT), there was displacement of mediastinal structures and compression of the oesophagus (Fig 2). The patient underwent six cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (liposomal doxorubicin), which resulted in stable disease. Preoperative CT and magnetic resonance imaging suggested no local invasion, although the margins from the oesophagus were indistinct (Fig 2 and supplementary images and videos).

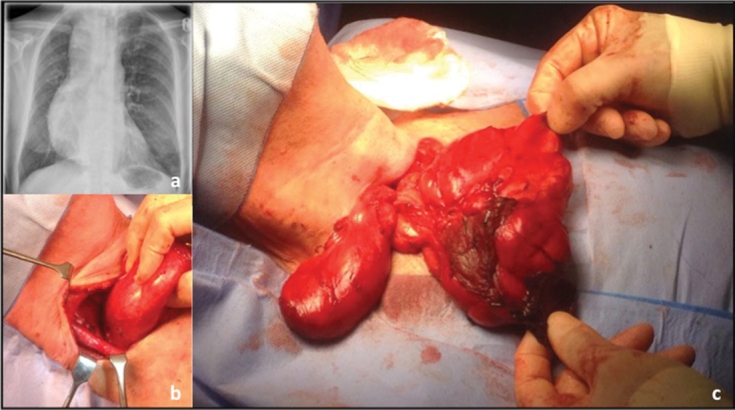

Figure 1.

Preoperative chest x-ray showing mediastinal mass (a); neck dissection and superior component of the tumour (b, c).

Figure 2.

Preoperative computed tomography of the tumour; displacement and compression of the oesophagus is seen, as well as the tumour’s proximity to other mediastinal structures.

Surgery was undertaken as a joint procedure by thoracic and ear, nose and throat teams. Excision of the mass was performed via a right-sided collar incision (Fig 1), sternotomy and right posterolateral thoracotomy through the fifth intercostal space. The tumour was found to extend from just inferior to the mandible on the right, down to the oesophageal hiatus. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve was intentionally sacrificed as it was extensively involved in dense adhesions around the tumour. The size of the superior component prevented it passing through the thoracic inlet, so excision as a single mass was not possible. The tumour was clamped at its thinnest point, divided and oversewn. This superior component was then removed.

A sternotomy allowed further dissection, so the residual cervical component of the tumour could be mobilised posterior to the brachiocephalic artery and the right subclavian vein. Some areas were particularly fixed and this incision provided good access in case of haemorrhage. The patient was then turned and positioned for a right posterolateral thoracotomy. The tissues around the thoracic duct were dissected and clipped to prevent chyle leak. The phrenic nerve was identified and preserved on a pedicle of pleura. In places, the lung was adherent to the tumour and was separated using a LigaSure™ device (Medtronic). Extensive dissection was required around the oesophagus, the identification of which was aided by the insertion of a nasogastric tube. It was thought that the tumour originated from the oesophagus, as the muscular layers were intimately involved in the mass and only the mucosal layer of the mid and distal oesophagus remained after tumour resection. The oesophagus was later excluded from the pleural space using a sheet of pleura. There was no overt oesophageal perforation and the nasogastric tube was kept in place at the end of surgery. The residual tumour mass in the neck was passed through the thoracic inlet and removed with the mediastinal component via the thoracotomy incision. There was a minor air leak from the lung parenchyma, which was oversewn prior to final water washouts and closure. The estimated total blood loss from the procedure was 250 ml. The wound was closed over two 28Ch chest drains. The patient was transferred to intensive care for monitoring overnight and then to the thoracic ward.

On the second postoperative day, nasogastric feeding was commenced. Flexible bronchoscopy and video-fluoroscopy confirmed a dysfunctional swallow and some aspiration. Speech and language therapy contributed to a gradual and significant improvement. The patient received a course of intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam for a lower respiratory tract infection and had a single episode of fast atrial fibrillation, which was managed with digoxin. The inpatient stay was intentionally prolonged in anticipation of a late oesophageal leak, which fortunately did not occur. The patient was discharged home on day 14.

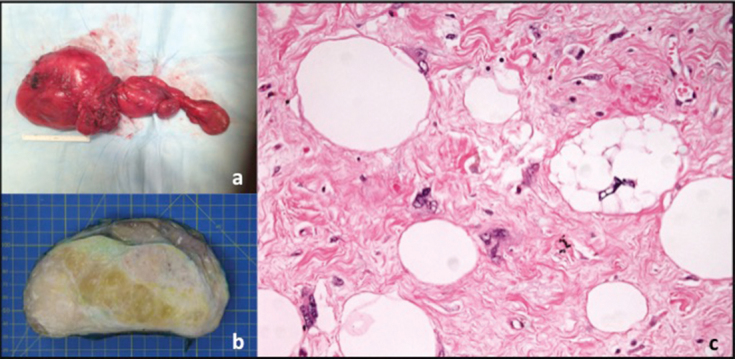

Histology confirmed complete macroscopic excision of a capsulated grade 2 de-differentiated liposarcoma (Fig 3). The two tumour specimens had dimensions of 12 × 10 × 6 cm (cervical portion) and 30.5 × 16.5 × 8.5 cm (mediastinal portion) and a combined mass of 1.73 kg. Microscopically the mass was completely excised with minimal microscopic margins and no vascular invasion. Station 9 and 11R lymph nodes showed no evidence of malignancy.

Figure 3.

The excised tumour: a) excised mass. b) The cut surface of the tumour had a varied appearance with yellow fat-like areas, denser white areas and a grey myxoid appearance in places. c) Histology of dedifferentiated areas showed atypical lipoblasts together with sarcoma cells with irregular hyperchromatic nuclei (200 times magnification, haematoxylin and eosin stain).

Four months after discharge, the patient could manage a full diet and had vocal cord augmentation planned. Although microscopic margins were small, no postoperative radiotherapy was undertaken as it was considered that it would be unlikely to provide significant benefit. He will remain under long-term surveillance by the sarcoma oncologists.

Discussion

Liposarcomas are rare, accounting for less than 1% of all malignancies.1 They originate from adipose tissue and most commonly occur in the thighs or retroperitoneum.1 Their response to chemotherapy is variable and surgery is the mainstay of treatment.1,2 Primary mediastinal liposarcoma is very rare, accounting for less than 1% of all mediastinal tumours.1,3

Mediastinal liposarcomas present with symptoms caused by compression or invasion of intrathoracic structures, most commonly dyspnoea, tachypnoea and chest pain.1 They are often large before they are diagnosed. Despite the extensive size of this patient’s tumour, he denied any specific symptoms at presentation other than a painless neck lump.

Intraoperatively, it appeared that this tumour arose from the oesophagus. Oesophageal liposarcomas are even rarer than those in other mediastinal sites, with few cases reported in the literature.4,5 The majority are intraluminal masses, causing symptoms of dysphagia, nausea and weight loss.4,5 They are also generally of the well-differentiated or myxoid subtype,4,5 rather than the de-differentiated subtype in this case, and are often managed with oesophagectomy.4 The oesophageal liposarcomas reported in the literature were all smaller than in this instance, with a mean maximal dimension of 13 cm (range 4–23 cm).5

Although thoracoscopic removal of mediastinal liposarcomas has been reported,2 open surgery remains the main approach, either via thoracotomy, sternotomy or hemi-clamshell incisions.2,3 In this case, the tumour size and position necessitated a multiple incision approach for resection.

De-differentiated liposarcoma is more likely to recur locally and metastasise than the differentiated subtype (although less than atypical, myxoid or pleomorphic subtypes).2,3 This recurrence may be delayed for up to 10 years.1

Surgical excision remains the mainstay of mediastinal liposarcoma treatment. In this case, the use of a tri-incision approach allowed macroscopic complete excision of a massive tumour extending from the mandible to oesophageal hiatus. It also ensured good access in case of complications from haemorrhage. Intraoperative insertion of a nasogastric tube was extremely useful to aid identification of the oesophagus during dissection. Regular follow-up is essential to detect disease recurrence.

References

- 1.Barbetakis N, Samanidis G, Paliouris D et al. A rare cause of mediastinal mass: primary liposarcoma. J Buon 2008; : 429–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decker JR, de Hoyos AL, DeCamp MM. Successful thoracoscopic resection of a large mediastinal liposarcoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; : 1,499–1,501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn HP, Fletcher CD. Primary mediastinal liposarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2007; : 1,868–1,874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia M, Buitrago E, Bejarano PA, Casillas J. Large oesophageal liposarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004; : 922–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin ZC, Chan XZ, Huang XF et al. Giant liposarcoma of the oesophagus: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2015: (33): 9,827–9,832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]