Key Points

Question

Can treatment using varenicline tartrate and medical management reduce heavy drinking and increase smoking abstinence in individuals with alcohol use disorder and comorbid cigarette smoking?

Findings

In this phase 2, randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial involving 131 participants with alcohol use disorder, varenicline effects varied in men and women. Men taking varenicline demonstrated a benefit on measures of heavy drinking, whereas women had a better response taking placebo; 13% of participants quit smoking while taking varenicline, but no one quit while taking placebo.

Meaning

Varenicline, an approved smoking-cessation medication, may have a role in the treatment of alcohol use disorder among men who smoke cigarettes.

Abstract

Importance

Individuals with alcohol use disorder have high rates of cigarette smoking. Varenicline tartrate, an approved treatment for smoking cessation, may reduce both drinking and smoking.

Objectives

To test the efficacy of varenicline with medical management for patients with alcohol use disorder and comorbid smoking seeking alcohol treatment, and to evaluate the secondary effects on smoking abstinence.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This phase 2, randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at 2 outpatient clinics from September 19, 2012, to August 31, 2015. Eligible participants met alcohol-dependence criteria and reported heavy drinking (≥5 drinks for men and ≥4 drinks for women) 2 or more times per week and smoking 2 or more times per week; 131 participants were randomized to either varenicline or placebo stratified by sex and site. All analyses were of the intention-to-treat type. Data analysis was conducted from February 5, 2016, to September 29, 2017.

Interventions

Varenicline tartrate, 1 mg twice daily, and matching placebo pills for 16 weeks. Medical management emphasized medication adherence for 4 weeks followed by support for changing drinking.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Percentage of heavy drinking days (PHDD) weeks 9 to 16, no heavy drinking days (NHDD) weeks 9 to 16, and prolonged smoking abstinence weeks 13 to 16.

Results

Of 131 participants, 39 (29.8%) were women and 92 (70.2%) were men, the mean (SD) age was 42.7 (11.7) years, and the race/ethnicity self-identified by most respondents was black (69 [52.7%]). Sixty-four participants were randomized to receive varenicline, and 67 to receive placebo. Mean change in PHDD between varenicline and placebo across sex and site was not significantly different. However, a significant treatment by sex by time interaction for PHDD (F1,106 = 4.66; P = .03) revealed that varenicline compared with placebo resulted in a larger decrease in log-transformed PHDD in men (least square [LS] mean difference in change from baseline, 0.54; 95% CI, −0.09 to 1.18; P = .09; Cohen d = 0.45) but a smaller decrease in women (LS mean difference, −0.69; 95% CI, −1.63 to 0.25; P = .15; Cohen d = −0.53). Thirteen of 45 men (29%) had NHDD taking varenicline compared with 3 of 47 men (6%) taking placebo (Cohen h = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.22-1.03), whereas 1 of 19 women (5%) had NHDD compared with 5 of 20 women (25%) taking placebo (Cohen h = −0.60; 95% CI, −1.21 to 0.04). Taking varenicline, 8 of 64 participants (13%) achieved prolonged smoking abstinence; no one (0 of 67) quit smoking taking placebo (P = .003; Cohen h = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.38-1.07).

Conclusions and Relevance

Varenicline with medical management resulted in decreased heavy drinking among men and increased smoking abstinence in the overall sample. Varenicline could be considered to promote improvements in men with these dual behavioral health risks.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01553136

This randomized clinical trial examined the effect of varenicline treatment with medical management on individuals with alcohol use disorder and comorbid cigarette smoking.

Introduction

Effective interventions for reducing co-occurring health risks, such as heavy alcohol use and smoking, have the potential to benefit patients and reduce health care costs. Cigarette smoking, the leading cause of disability and death, is more than twice as common among individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) than among the general population, and combined smoking and heavy drinking has negative synergistic effects on health. Cigarette smoking also predicts poorer treatment outcome among patients seeking alcohol treatment. Neither naltrexone hydrochloride nor acamprosate calcium, which are approved pharmacotherapies for AUD, promotes reductions in smoking during treatment of AUD. Thus, identifying pharmacotherapies to treat both AUD and smoking represents an important step in integrating addiction treatment into mainstream health care.

One potential medication is varenicline tartrate, which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as treatment for smoking cessation that acts at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors involved in both alcohol and nicotine reward. Varenicline reduced alcohol seeking and consumption and attenuated dopamine release to combined ethanol and nicotine administration in preclinical studies; it also reduced alcohol use in human laboratory and pilot smoking-cessation trials. However, two 12-week multisite studies of varenicline for the treatment of AUD in mixed samples of smokers and nonsmokers had conflicting results. Litten and colleagues found that varenicline resulted in a significantly lower percentage of heavy drinking days in combination with a 6-session computerized bibliotherapy. Furthermore, among the subsample of smokers, those who reduced the number of cigarettes smoked had larger reductions in drinking. Subsequently, de Bejczy and colleagues did not find an effect of varenicline when tested in the absence of specific psychosocial counseling. The de Bejczy et al study did not report smoking outcomes. The Litten et al trial results, however, suggested that varenicline should be tested further in patients with AUD who also smoke.

To further evaluate the efficacy of varenicline for AUD, we recruited individuals with comorbid AUD and smoking for a randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial at 2 sites. In addition to hypothesizing an effect on alcohol consumption, we anticipated that varenicline would promote smoking abstinence, thereby providing an added benefit. The study design adopted methods from the smoking-cessation field in which patients prepare for a future “quit date” and initiate medication prior to that date. Thus, our study incorporated a 4-week period on medication that emphasized medication adherence prior to active efforts to change drinking. This period was followed by 12 additional weeks of treatment to allow changes in drinking and smoking to emerge. In a study of varenicline for smoking cessation, 1-week point prevalence abstinence from smoking continued to increase over 4 weeks after the quit date, and in the Litten et al trial, the effects of varenicline on heavy drinking became more pronounced over time. Thus, the primary drinking outcome in our study—percentage of heavy drinking days (PHDD)—was evaluated following an initial 8-week grace period. Our secondary outcome—prolonged smoking abstinence with biochemical confirmation—was assessed during the last 4 weeks of treatment, which is consistent with the efficacy and safety studies of varenicline for smoking cessation.

Methods

Design Overview

This phase 2, randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluated the effects of varenicline combined with medical management (MM) on alcohol drinking. It involved 131 alcohol-dependent smokers seeking treatment for alcohol use but not for smoking. Its secondary aim was to evaluate the effects of varenicline on smoking cessation. Participants were seen over a 16-week treatment period and had follow-up at weeks 26, 39, and 52. The results of the recruitment and treatment period, from September 19, 2012, to August 31, 2015, are presented here. This trial was approved by the institutional review boards of Columbia University and Yale School of Medicine as well as the Western Institutional Review Board, obtained a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and was monitored by a Data and Safety Monitoring Board. All participants provided written informed consent. Data analysis was conducted from February 5, 2016, to September 29, 2017. See the Supplement for the trial protocol.

Setting and Participants

The trial was conducted at 2 outpatient substance abuse treatment and research facilities (one affiliated with Columbia University, New York, New York, and the other affiliated with Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut).

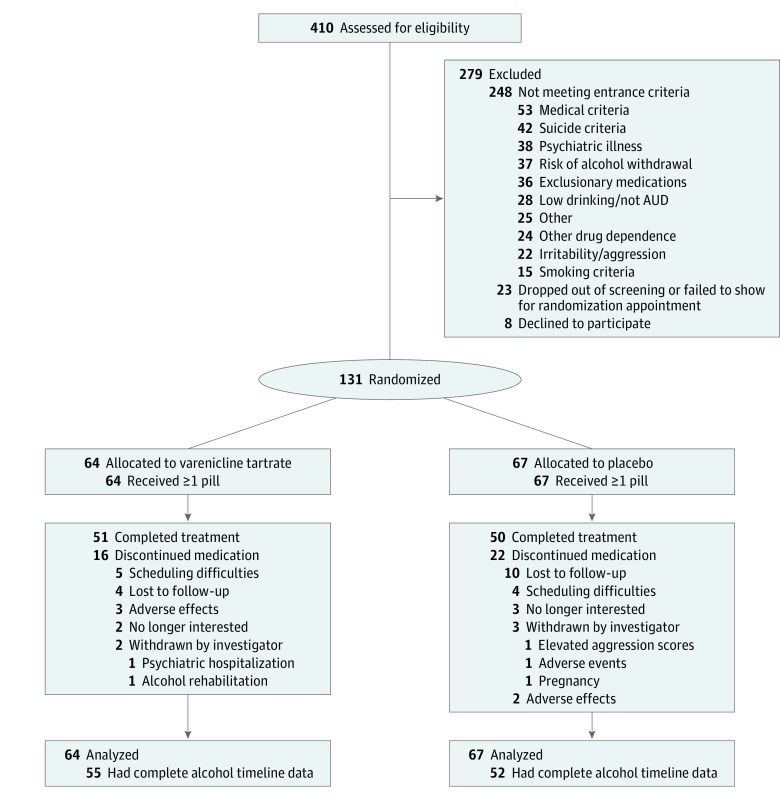

Participants were recruited primarily through print, radio, and social media advertisements and community outreach to health care professionals. After initial screening, participants were invited to an in-person intake appointment. Figure 1 presents the flow of participants.

Figure 1. Enrollment and Follow-up Flow Diagram.

AUD indicates alcohol use disorder.

Eligible participants were men and women aged 18 to 70 years who met alcohol-dependence criteria, according to the DSM-IV-TR, and who reported heavy drinking 2 or more times a week for the previous 90 days and 7 or fewer consecutive days of abstinence prior to intake. After the first 24 participants, the minimum smoking criteria were expanded to increase recruitment from daily smoking (5 or more cigarettes, carbon monoxide level of 6 ppm or greater, or plasma cotinine level of 40 ng/mL or greater [to convert to nanomoles per milliliter, multiply by 5.675]) to nondaily smoking (2 or more times per week, urine cotinine level of 30 ng/mL or greater, or plasma cotinine level of 6 ng/mL or greater).

The key exclusion criteria were current, clinically significant disease or abnormality; diagnosis of a serious psychiatric illness; current suicidal ideation or lifetime history of suicidal behavior; risk of aggression; current diagnosis of drug dependence, excluding nicotine or marijuana; risk of clinically significant alcohol withdrawal; medications in the past 3 months to treat alcohol or tobacco dependence; and psychotropic medications in the past month (but a stable dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor was allowed). Women of childbearing age could not be pregnant or nursing and had to be practicing effective contraception.

Randomization and Interventions

Randomization to 2 mg of varenicline tartrate (n = 64) or matching placebo pills (n = 67) was stratified by site and sex within site (block size of 4). Stratification by sex was based on findings that men and women differ in their smoking and drinking behavior, and their response to smoking and alcohol treatment. The randomization list was generated by our study statistician (R.G.) and was implemented through a web-based system (Endpoint Systems). Pfizer, Inc supplied active medications and matching placebo pills, and Catalent, Inc packaged the medications in blister packs dispensed at every treatment session. Participants, treatment providers, and research staff were blind to the assignment throughout the study. In 2 cases involving suicidal behavior or hospitalization for suicidality, our principal investigators (S.O. and A.Z.), who did not interact with the participant, were unblinded to meet reporting requirements.

Medication titration followed these standard doses: 0.5 mg once daily for 3 days, 0.5 mg twice daily for 4 days, and 1 mg twice daily for the remainder of the 16-week treatment. After week 16, use of medication was tapered over 2 weeks (0.5 mg twice daily and then 0.5 mg daily). Dose reductions were permitted, and those who discontinued medication could continue research and counseling appointments. Daily medication adherence was monitored through a combination of pill counts returned from blister packs and self-reported compliance with the Timeline Follow-Back procedures.

Following randomization, participants attended 12 treatment research sessions (weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, and 17) and met with a medical professional for MM adapted from the COMBINE study. The first 4 sessions addressed tolerability and supported medication adherence; the remaining sessions addressed finalizing drinking goals as well as developing and implementing strategies for changing drinking. Three videos were viewed during treatment to standardize the discussions regarding drinking goals and strategies. The initial session took approximately 60 minutes, and the remaining sessions took 15 to 20 minutes. Smoking cessation was not addressed, but a faxed referral to the state Tobacco Quitline was offered at the last session.

Assessments

Trained research assistants administered the Timeline Follow-Back Interview at intake for the previous 90 days and at each session to record daily drinking and smoking. Carbon monoxide and plasma cotinine were measured at intake and at monthly sessions to confirm smoking. Adverse events using the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Effects (with individual adverse events coded as mild, moderate, severe, life threatening, or fatal), the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (comprising multiple subscales and score ranges), the Overt Aggression Scale (comprising multiple subscales and score ranges), and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (score range: 10-50, with the higher score indicating greater positive or negative affect on the corresponding subscales) were measured at every session. Other secondary measures were obtained but are not reported here.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were of the intention-to-treat type. The primary drinking outcome, PHDD, was summarized during the last 8 weeks of treatment and analyzed using a linear mixed model, with treatment group (varenicline or placebo), site (New York or New Haven), sex (male or female), time (baseline or end point), and all of their interactions as categorical predictors. Baseline PHDD measure was calculated over the 8 weeks prior to intake. All available data were included in the model, and an unstructured variance-covariance matrix was used. Heavy drinking day was defined as consuming 5 (for men) and 4 (for women) or more standard drinks containing 14 g of ethanol.

In accordance with FDA recommendations, we performed an analysis of responders as an efficacy end point, using the responder definition of no heavy drinking days (NHDD; never drinking 4 or more drinks within a day for women or 5 or more drinks within a day for men), during the last 8 weeks and then computed effect-size estimates by sex. The NHDD outcome was a clinical benefit and considered a surrogate for how patients feel and function. The FDA suggests this outcome can be assessed after a grace period if the maximal drug effect is thought to take time.

The secondary outcome, prolonged abstinence (PA) from smoking, was analyzed with Fisher exact test. Prolonged abstinence was defined as self-reported abstinence in the last 28 days, as confirmed by plasma cotinine levels of less than 6 ng/mL (changed from a cotinine level of less than 15 ng/mL to detect nondaily smoking) with missing data treated as smoking. During the final 28 days of treatment, PA was the primary within-treatment efficacy outcome in the pivotal trials of varenicline.

The trial was powered for a medium effect size (Cohen d = 0.5) for the between-group difference on the primary outcome. With 64 participants per group, power to detect such an effect was at least 80%, assuming α = .05 and a 2-sided test. We did not consider site and sex effects in the power calculations. To allow for dropouts, we planned to recruit 160 participants; however, the trial closed at 131 owing to slower-than-anticipated recruitment.

All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). We used overall F tests for interactive and main effects in the models, and t tests for post hoc comparisons. All tests were 2-tailed, and the significance level was P = .05.

Results

Participants

A total of 131 alcohol-dependent smokers were recruited and treated between September 19, 2012, and August 31, 2015. Among the 131 participants, 39 (29.8%) were women and 92 (70.2%) were men, the mean (SD) age was 42.7 (11.7) years, and the race/ethnicity self-identified by most respondents was black (69 [52.7%]). All participants received at least 1 medication dose (first dose was observed). Baseline characteristics by treatment group and sex are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Condition and Sex.

| Variable | Male Participants, No. (%) | Female Participants, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who Received Varenicline Tartrate (n = 45) |

Who Received Placebo (n = 47) |

Who Received Varenicline (n = 19) |

Who Received Placebo (n = 20) |

|

| Demographics | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 15 (33) | 15 (32) | 11 (58) | 9 (45) |

| Black/African American | 28 (62) | 26 (55) | 6 (32) | 9 (45) |

| Othera | 2 (4) | 6 (13) | 2 (11) | 2 (10) |

| Hispanic | 5 (11) | 6 (13) | 0 (0) | 4 (20) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 43 (12) | 43 (12) | 45 (11) | 40 (12) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kgb | 83 (13) | 86 (17) | 71 (17) | 82 (17) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26 (4) | 27 (5) | 26 (6) | 30 (6) |

| Highest level of educationc | ||||

| ≥High school | 15 (33) | 21 (46) | 4 (21) | 10 (50) |

| Some college | 19 (42) | 13 (28) | 6 (32) | 6 (30) |

| College/postbaccalaureate | 11 (24) | 12 (26) | 9 (47) | 4 (20) |

| Employed full- or part-time | 20 (44) | 27 (57) | 12 (63) | 9 (45) |

| Married | 9 (20) | 4 (9) | 4 (21) | 7 (35) |

| Alcohol consumption characteristicsd | ||||

| Drinks per drinking day, mean (SD) | 9 (4) | 9 (4) | 8 (5) | 8 (4) |

| Days abstinent, mean (SD), % | 17 (18) | 20 (17) | 25 (20) | 25 (20) |

| Days heavy drinking, mean (SD), % | 63 (26) | 61 (25) | 65 (23) | 63 (25) |

| Other alcohol-related characteristics | ||||

| Alcohol treatment history | 12 (27) | 12 (26) | 7 (37) | 5 (25) |

| Positive family history of alcoholismb,c | 17 (41) | 18 (40) | 5 (28) | 0 (0) |

| Age at onset alcohol dependence, mean (SD), y | 30 (10) | 25 (8) | 34 (11) | 28 (9) |

| ADS total score, mean (SD)b,e | 12.6 (5.6) | 13.2 (6.9) | 16.4 (6.0) | 16.7 (6.4) |

| ImBIBe total score, mean (SD)f | 15.3 (7.5) | 17.5 (8.4) | 16.2 (6.5) | 17.7 (7.3) |

| OCDS total score, mean (SD)g | 12.1 (7.8) | 13.0 (6.1) | 14.2 (6.2) | 15.7 (8.1) |

| Treatment goal of total abstinencec | 7 (16) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| Ethyl glucuronide level ≥200 ng/mL | 25 (56) | 23 (49) | 13 (68) | 13 (65) |

| Smoking characteristics | ||||

| FTND score, mean (SD)b,h | 4.8 (2.7) | 5.1 (2.5) | 3.5 (2.5) | 3.1 (2.2) |

| Daily smokersb,i,j | 43 (96) | 43 (91) | 15 (79) | 17 (85) |

| Cigarettes per smoking day, mean (SD)b,i | 13 (8) | 12 (7) | 10 (6) | 8 (6) |

| Age at daily smoking, mean (SD), yc | 18 (5) | 19 (6) | 20 (6) | 18 (6) |

| ≥1 Previous quit attemptc | 31 (69) | 33 (72) | 13 (68) | 13 (65) |

| Smoking treatment goalb,k | 22 (49) | 16 (34) | 15 (79) | 15 (75) |

| QSU score–Desire and Intention, mean (SD)l | 4.2 (2.3) | 4.8 (1.9) | 4.5 (2.4) | 3.6 (1.9) |

| QSU score–Relief from Withdrawal or Negative Affect, mean (SD)b,c,m | 2.5 (1.9) | 2.5 (1.3) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.7) |

| Carbon monoxide level, mean (SD), ppmb | 10.8 (5.7) | 10.9 (6.5) | 7.4 (9.5) | 8.2 (5.5) |

| Plasma cotinine level, mean (SD), ng/mLb,c | 194.6 (111.4) | 228.3 (152.2) | 140.1 (91.7) | 161.1 (153.5) |

| Other characteristics | ||||

| HRQOL score, mean (SD)c,n | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.7 (0.7) |

| PANAS score– Positive Affect, mean (SD)o | 30 (8.7) | 29.5 (9.2) | 33.7 (7.8) | 29.8 (8.5) |

| PANAS score–Negative Affect, mean (SD)b,p | 16.0 (5.3) | 16.6 (7.5) | 20.8 (8.0) | 17.6 (7.8) |

| Marijuana use (≥1 d/wk)i | 5 (11) | 5 (11) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Stable dose of SSRI (≥2 mo)b | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (11) | 3 (15) |

Abbreviations: ADS, alcohol dependence scale; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); FTND, Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; OCDS, Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale; ImBIBe, Impact of Beverage Intake on Behavior; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; QSU, Questionnaire of Smoking Urges; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

SI conversion factor: To convert to nanomoles per milliliter, multiply by 5.675.

Other includes Asian, Native American/Alaska Native, more than 1 race, and unknown.

Significant differences exist between men and women when tested without treatment condition.

Based on available data; there are missing values for this variable.

Consumption over the course of 8 weeks prior to intake.

Scores range from 0 to 47, with greater scores indicating a higher level of alcohol dependence.

Scores range from 0 to 48 based on 12 items, with greater scores indicating more consequences owing to drinking.

Scores range from 0 to 40, with greater scores indicating more severe craving.

Scores range from 0 to 11, with greater scores indicating a higher level of nicotine dependence.

Based on the 4 weeks prior to intake.

Smoked at least 25 of 28 days.

Participants indicated their goal as “definitely” try to cut down or stop smoking while trying to reduce their drinking.

Scores range from 1 to 7, with greater scores indicating more desire and intention to smoke.

Scores range from 1 to 7, with greater scores indicating more desire for relief from withdrawal and negative affect.

Scores range from 1 to 5, with greater scores indicating poorer general health. The single question from the HRQOL was, “Would you say that in general your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?”

Scores range from 10 to 50, with greater scores indicating more positive affect.

Scores range from 10 to 50, with greater scores indicating more negative affect.

Medication Adherence and Participation

The varenicline (n = 64) and placebo (n = 67) treatment groups were similar in the median (interquartile range [IQR]) percentage of pills taken out of the total possible pills over the 16-weeks treatment period (85% [45%-98%] vs 81% [39%-96%]). However, women receiving varenicline took fewer pills (median [IQR], 58% [20%-93%]) than did men receiving varenicline (median [IQR], 91% [55%-99%]) and were more likely than men to reduce or discontinue use of varenicline (7 of 19 [37%] vs 2 of 45 [4%]). In the placebo groups, the median (IQR) percentage of pills taken was similar for men (80% [28%-94%]) and women (83% [52%-98%]). The median (IQR) number of treatment sessions attended was comparable between men and women taking varenicline (12 [9-12] vs 12 [10-12]) and taking placebo [12 [7-12] vs 11 [11-12]). Complete drinking data were available for 38 of 45 men (84%) and for 17 of 19 women (89%) taking varenicline as well as for 36 of 47 men (77%) and 16 of 20 women (80%) taking placebo.

Alcohol Outcomes

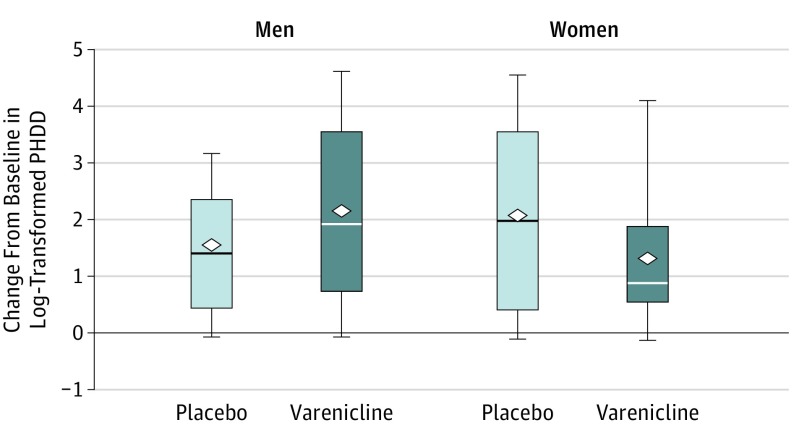

On PHDD during the last 8 weeks of treatment (log transformed), the mean change from baseline did not differ (F1,106 = 0.06; P = .80) between varenicline (least square [LS] mean [SE], 1.69 [0.20]) and placebo (LS mean [SE], 1.77 [0.20]) across sex and site. However, the results revealed a significant medication by sex by time interaction (F1,106 = 4.66; P = .03). Varenicline compared with placebo resulted in a greater decrease in PHDD in men (LS mean difference for change from baseline, 0.54; 95% CI, −0.09 to 1.18; P = .09; Cohen d = 0.45) and with a smaller decrease in PHDD in women (LS mean difference, −0.69; 95% CI, −1.63 to 0.25; P = .15; Cohen d = −0.53), as shown in Figure 2. No other treatment interactions were significant.

Figure 2. Change From Baseline to End Point in Log-Transformed Percentage of Heavy Drinking Days (PHDD) Outcome by Treatment Group and Sex.

Heavy drinking days were defined as 5 or more drinks within a day for men and 4 or more drinks within a day for women. Baseline was defined as the 8 weeks prior to intake. End point was defined as the last 8 weeks of the treatment period. The horizontal line in the middle of each box indicates the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The diamonds indicate mean values. The whiskers above and below the boxes mark the minimum value and the maximum value, respectively. Varenicline was given as varenicline tartrate.

In a responder analysis, we examined the effect of varenicline on NHDD during the last 8 weeks of treatment. When missing data were treated as heavy drinking, 13 of 45 men (29%) had NHDD taking varenicline compared with 3 of 47 men (6%) taking placebo (Cohen h = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.22-1.03), whereas 1 of 19 women (5%) had NHDD taking varenicline compared with 5 of 20 women (25%) taking placebo (Cohen h = −0.60; 95% CI, −1.21 to 0.04). Results were similar when missing data were treated as missing.

Smoking Outcomes

On PA, varenicline, compared with placebo, resulted in greater abstinence from smoking during the last 28 days of treatment (8 of 64 [13%] vs 0 of 67 [0%]; P = .003; Cohen h = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.38-1.07).

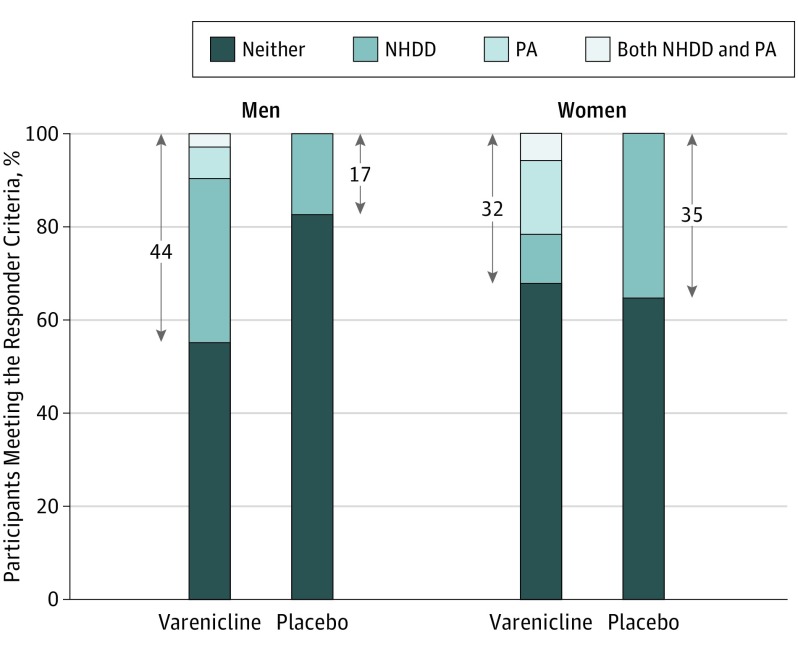

Integrated Responder Analysis

Using definitions of good response for alcohol (NHDD) and smoking (PA) during the last 4 weeks of treatment, Figure 3 displays the proportion of participants, categorized by sex and treatment condition, who responded by meeting one or both outcomes or who failed to respond. On this exploratory integrated outcome, a marked advantage of varenicline over placebo was seen in men (20 of 45 [44%] vs 8 of 47 [17%]; Cohen h = 0.60) but not in women (6 of 19 [32%] vs 7 of 20 [35%]; Cohen h = −0.06).

Figure 3. Percentage of Participants Meeting the Responder Criteria by Treatment Group and Sex.

Positive response on the integrated response measure was defined as either No Heavy Drinking Days (NHDD), Prolonged Smoking Abstinence (PA), or both during the last 28 days of treatment. Percentages within the arrows correspond to the percentage who had a good response on the integrated measure. Missing data were treated as nonresponse. Varenicline treatment had a higher integrated response rate than placebo for men (Cohen h = 0.60) but not for women (Cohen h = –0.06). Varenicline was given as varenicline tartrate.

Adverse Events and Mood

Varenicline was generally well tolerated. On the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Effects interview (Table 2), abnormal dreaming was reported by substantially more patients in the varenicline condition. Women taking varenicline were more likely to report this complaint (13 of 19 [68%]) than men taking varenicline (15 of 45 [33%]) and than women and men taking placebo (4 of 20 [20%] vs 11 of 47 [23%]). Three serious adverse events occurred in the active treatment group: psychiatric hospitalization for suicidal ideation, alcohol rehabilitation following suicidal behavior (trying to drink to death), and overnight hospitalization for blood pressure monitoring. Two events occurred in the placebo group: psychiatric hospitalization in the 30 days following treatment and hospitalization for an infection. On the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule scale, the mean (SD) peak change in negative affect from baseline was lower on varenicline (1.80 [5.33]) than with placebo (3.53 [5.32]). The Overt Aggression Scale and Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale scores were similar.

Table 2. Emergent Adverse Events by Treatment Condition and Sexa.

| Adverse Event | Male Participants, No. (%) | Female Participants, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who Received Varenicline Tartrate (n = 45) |

Who Received Placebo (n = 47) |

Who Received Varenicline (n = 19) |

Who Received Placebo (n = 20) |

|

| Cardiopulmonary | ||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 3 (16) | 2 (10) |

| Central nervous system/psychiatric | ||||

| Anxiety | 4 (9) | 4 (9) | 4 (21) | 2 (10) |

| Depression | 8 (18) | 3 (6) | 3 (16) | 5 (25) |

| Disturbance in attention | 4 (9) | 3 (6) | 2 (11) | 2 (10) |

| Dizziness | 3 (7) | 2 (4) | 5 (26) | 2 (10) |

| Drowsiness | 6 (13) | 7 (15) | 0 | 3 (15) |

| Fatigue | 6 (13) | 9 (19) | 3 (16) | 4 (20) |

| Headache | 7 (16) | 9 (19) | 9 (47) | 6 (30) |

| Insomnia | 4 (9) | 6 (13) | 6 (32) | 3 (15) |

| Irritability | 12 (27) | 13 (28) | 8 (42) | 7 (35) |

| Abnormal dreams | 15 (33) | 11 (23) | 13 (68) | 4 (20) |

| Ear, nose, throat | ||||

| Rhinorrhea (runny nose) | 8 (18) | 4 (9) | 3 (16) | 5 (25) |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Acid reflux | 3 (7) | 4 (9) | 2 (11) | 1 (5) |

| Constipation | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 3 (16) | 6 (30) |

| Decreased appetite | 5 (11) | 7 (15) | 6 (32) | 4 (20) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (7) | 7 (15) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) |

| Dry mouth | 6 (13) | 2 (4) | 4 (21) | 3 (15) |

| Dyspepsia | 2 (4) | 5 (11) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Flatulence | 4 (9) | 5 (11) | 6 (32) | 3 (15) |

| Taste perversion | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 2 (11) | 2 (10) |

| Increased appetite | 7 (16) | 5 (11) | 4 (21) | 5 (25) |

| Increased bowel movements | 3 (7) | 0 | 1 (5) | 2 (10) |

| Nausea | 12 (27) | 9 (19) | 13 (68) | 9 (45) |

| Vomiting | 4 (9) | 3 (6) | 0 | 4 (20) |

| Genitourinary | ||||

| Frequent urination | 7 (16) | 4 (9) | 5 (26) | 3 (15) |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||

| Joint pain or swelling | 2 (4) | 4 (9) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Ophthalmological | ||||

| Blurred vision | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (16) | 1 (5) |

| Skin | ||||

| Diaphoresis (sweating) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 2 (11) | 2 (10) |

Adverse events reported on the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Effects as new onset or at greater severity than baseline in more than 5% of either treatment group collapsed across sex.

Discussion

This study examined the efficacy of varenicline combined with MM for the treatment of AUD in individuals with comorbid smoking. The mean change in PHDD in the overall sample was not different by medication condition. However, varenicline had different effects on drinking in men and women. Men appeared to derive benefit from varenicline, compared with placebo, on measures of heavy drinking, whereas women did better taking placebo. Although participants were not seeking or provided smoking-cessation counseling, the overall sample receiving varenicline experienced a significant increase in 1-month prolonged smoking abstinence at the end of treatment.

Compared with previous trials that included smokers and nonsmokers with AUD, our trial enrolled smokers exclusively, had a longer treatment duration, and used a more intensive behavioral intervention that incorporated methods on preparing to quit from the literature. Unlike the Litten et al trial, which found an overall advantage of varenicline over placebo that was not moderated by sex, our study found that, on PHDD, only men appeared to benefit from varenicline combined with MM. This benefit also extended to NHDD, the FDA-preferred outcome. The moderating role of sex was not examined in the negative trial by de Bejczy and colleagues, which did not provide counseling.

In our study, sex differences in the effects of varenicline combined with MM may be due to several factors. Women differed from men on baseline characteristics (eg, greater severity of alcohol dependence; lower nicotine dependence and smoking intensity); thus, causality cannot be attributed to sex. From a methodological perspective, we permitted dose reductions to minimize adherence problems because lower varenicline doses are effective for smoking cessation. More women than men reduced or discontinued their dose perhaps owing to lower tolerability, a finding consistent with results in other trials indicating that women are more likely to report adverse effects from varenicline. Finally, the small sample size for women limits the reliability of effect estimates.

Varenicline resulted in significantly higher rates of smoking abstinence compared with placebo (13% vs 0%), even though participants were not seeking or provided smoking-cessation counseling. These findings have important clinical implications given that less than 10% of smokers report readiness to quit smoking in the next month; individuals treated for alcoholism are more likely to die of smoking than from alcohol-related causes; and smoking cessation substantially lowers the risk of lung and other cancers, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Furthermore, most alcohol-dependent smokers do not receive smoking-cessation assistance, yet heavy-drinking smokers see these behaviors as highly associated.

In an exploratory integrated responder analysis, there was little overlap in the response to varenicline on the categorical outcomes of PA and NHDD during the last 28 days of treatment. Examining good response measured by NHDD and/or PA, we observed that the marked advantage of varenicline over placebo in men vs women (44% vs 17%) was driven largely by reduced drinking. In women, the percentage who had a good response was equivalent for varenicline (32%) and placebo (35%), with smoking abstinence predominating with varenicline. For both sexes, the percentage who met the criteria for both NHDD and PA on varenicline was small, and good response in the placebo condition was related exclusively to improvements in drinking. For these analyses, we used biochemical confirmation of self-reported smoking abstinence; however, biomarkers of alcohol consumption, such as ethyl glucuronide, have not been validated for distinguishing heavy drinking from lower levels of drinking. Thus, heavy drinking may have been underreported.

Information on varenicline safety in smokers with current AUD has been limited because this population has been excluded from smoking-cessation trials. Our trial, together with 2 previous multisite trials, addresses this gap by noting low rates of adverse events, with only abnormal dreams—a common adverse event of varenicline—being substantially higher with varenicline than placebo, particularly among women. However, compared with participants in studies of smokers without current AUD, our participants reported abnormal dreams more frequently in both conditions, suggesting that patients with AUD may be at increased risk for this complaint. Of note, sleep problems are common among patients with AUD. Finally, negative affect scores were lower on varenicline, which is consistent with the findings of a laboratory study of smoking abstinence.

Limitations

The small sample size of women is an important limitation. Future studies should evaluate the effectiveness and safety of varenicline in women and men separately in larger samples to establish whether the observed effects are of clinical significance. Limits to the generalizability of the findings include the exclusion of those with other drug dependence, current suicidality or a history of suicidal behavior, significant irritability or aggression, and risk of significant alcohol withdrawal.

Conclusions

Among individuals seeking AUD treatment who also smoked cigarettes, the effect of varenicline did not differ from placebo in the overall sample, but differed between men and women. Varenicline, compared with placebo, resulted in greater reduction in heavy drinking in men but not in women. Smoking-cessation counseling was not provided, but varenicline resulted in higher smoking abstinence, which is consistent with the primary indication for varenicline. Thus, varenicline combined with MM appears to have potential as a treatment for the co-occurring health risk behaviors of heavy alcohol use and smoking in men.

Trial Protocol

References

- 1.Evers KE, Quintiliani LM. Advances in multiple health behavior change research. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(1):59-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prochaska JJ, Prochaska JO. A review of multiple health behavior change interventions for primary prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5(3):208-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawson DA. Drinking as a risk factor for sustained smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59(3):235-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuper H, Tzonou A, Kaklamani E, et al. Tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and their interaction in the causation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2000;85(4):498-502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. ; International Pancreatitis Study Group . Prognosis of chronic pancreatitis: an international multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(9):1467-1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrams DB, Rohsenow DJ, Niaura RS, et al. Smoking and treatment outcome for alcoholics: effects on coping skills, urge to drink, and drinking rates. Behav Ther. 1992;23:283-297. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80386-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelsi E, Vanbiervliet G, Chérikh F, et al. Factors predictive of alcohol abstention after resident detoxication among alcoholics followed in an hospital outpatient center. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31(6-7):595-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hintz T, Mann K. Long-term behavior in treated alcoholism: evidence for beneficial carry-over effects of abstinence from smoking on alcohol use and vice versa. Addict Behav. 2007;32(12):3093-3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason BJ, Lehert P. Effects of nicotine and illicit substance use on alcoholism treatment outcomes and acamprosate efficacy. J Addict Med. 2009;3(3):164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fucito LM, Park A, Gulliver SB, Mattson ME, Gueorguieva RV, O’Malley SS. Cigarette smoking predicts differential benefit from naltrexone for alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(10):832-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Specka M, Lieb B, Kuhlmann T, et al. Marked reduction of heavy drinking did not reduce nicotine use over 1 year in a clinical sample of alcohol-dependent patients. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(3):120-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee S, Bartlett SE. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as pharmacotherapeutic targets for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9(1):60-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, et al. Varenicline: an α4β2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005;48(10):3474-3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rollema H, Coe JW, Chambers LK, Hurst RS, Stahl SM, Williams KE. Rationale, pharmacology and clinical efficacy of partial agonists of α4β2 nACh receptors for smoking cessation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(7):316-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendrickson LM, Guildford MJ, Tapper AR. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: common molecular substrates of nicotine and alcohol dependence. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4(29):1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feduccia AA, Simms JA, Mill D, Yi HY, Bartlett SE. Varenicline decreases ethanol intake and increases dopamine release via neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171(14):3420-3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamens HM, Andersen J, Picciotto MR. Modulation of ethanol consumption by genetic and pharmacological manipulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010;208(4):613-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminski BJ, Weerts EM. The effects of varenicline on alcohol seeking and self-administration in baboons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(2):376-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Richards JK, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(30):12518-12523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ericson M, Löf E, Stomberg R, Söderpalm B. The smoking cessation medication varenicline attenuates alcohol and nicotine interactions in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329(1):225-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKee SA, Harrison EL, O’Malley SS, et al. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):185-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fucito LM, Toll BA, Wu R, Romano DM, Tek E, O’Malley SS. A preliminary investigation of varenicline for heavy drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;215(4):655-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell JM, Teague CH, Kayser AS, Bartlett SE, Fields HL. Varenicline decreases alcohol consumption in heavy-drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2012;223(3):299-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Fertig JB, et al. ; NCIG (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Clinical Investigations Group) Study Group . A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy of varenicline tartrate for alcohol dependence. J Addict Med. 2013;7(4):277-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Bejczy A, Löf E, Walther L, et al. Varenicline for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(11):2189-2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiore M, Jaen C, Baker T, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al. ; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group . Varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Connors GJ, Agrawal S. Assessing drinking outcomes in alcohol treatment efficacy studies: selecting a yardstick of success. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(10):1661-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al. ; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group . Efficacy of varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association ; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1035-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coccaro EF, Harvey PD, Kupsaw-Lawrence E, Herbert JL, Bernstein DP. Development of neuropharmacologically based behavioral assessments of impulsive aggressive behavior. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3(2):S44-S51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perkins KA. Sex differences in nicotine reinforcement and reward: influences on the persistence of tobacco smoking. Nebr Symp Motiv. 2009;55:143-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceylan-Isik AF, McBride SM, Ren J. Sex difference in alcoholism: who is at a greater risk for development of alcoholic complication? Life Sci. 2010;87(5-6):133-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenfield SF, Pettinati HM, O’Malley S, Randall PK, Randall CL. Gender differences in alcohol treatment: an analysis of outcome from the COMBINE Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(10):1803-1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawk LW Jr, Ashare RL, Lohnes SF, et al. The effects of extended pre-quit varenicline treatment on smoking behavior and short-term abstinence: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(2):172-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scharf D, Shiffman S. Are there gender differences in smoking cessation, with and without bupropion? Pooled- and meta-analyses of clinical trials of bupropion SR. Addiction. 2004;99(11):1462-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. Gender differences in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(4):555-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babor TF, Grant M, Acuda W, et al. A randomized clinical trial of brief interventions in primary care: summary of a WHO project. Addiction. 1994;89(6):657-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blow FC, Barry KL, Walton MA, et al. The efficacy of two brief intervention strategies among injured, at-risk drinkers in the emergency department: impact of tailored messaging and brief advice. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(4):568-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kranzler HR, Tennen H, Armeli S, et al. Targeted naltrexone for problem drinkers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(4):350-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. ; COMBINE Study Research Group . Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pettinati HM, Weiss RD, Dundon W, et al. A structured approach to medical management: a psychosocial intervention to support pharmacotherapy in the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2005;(15):170-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zweben A, Piepmeier ME, Fucito L, O’Malley SS. The clinical utility of the Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ) in an alcohol pharmacotherapy trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;77:72-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sobell L, Sobell M. Alcohol consumption measures In: Allen JP, Wilson V, et al. Assessing Alcohol Problems: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003:75-99. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levine J, Schooler NR. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1986;22(2):343-381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.US Food and Drug Administration Division Director’s Approval Memo. Paper presented at: NDA 21-8972006. [Google Scholar]

- 52.US Food and Drug Administration Alcoholism: Developing Drugs for Treatment. (No. FDA D-0152-001) . Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kline-Simon AH, Falk DE, Litten RZ, et al. Posttreatment low-risk drinking as a predictor of future drinking and problem outcomes among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(suppl 1):E373-E380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Falk D, Wang XQ, Liu L, et al. Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcohol clinical trials. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(12):2022-2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Falk DE, Castle IJ, Ryan M, Fertig J, Litten RZ. Moderators of varenicline treatment effects in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for alcohol dependence: an exploratory analysis. J Addict Med. 2015;9(4):296-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cahill K, Lindson-Hawley N, Thomas KH, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Halperin AC, McAfee TA, Jack LM, et al. Impact of symptoms experienced by varenicline users on tobacco treatment in a real world setting. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(4):428-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ravva P, Gastonguay MR, French JL, Tensfeldt TG, Faessel HM. Quantitative assessment of exposure-response relationships for the efficacy and tolerability of varenicline for smoking cessation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(3):336-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wewers ME, Stillman FA, Hartman AM, Shopland DR. Distribution of daily smokers by stage of change: current population survey results. Prev Med. 2003;36(6):710-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, et al. Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment: role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA. 1996;275(14):1097-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.US Department of Health and Human Services The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service. Office on Smoking and Health; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fucito LM, Hanrahan TH. Heavy-drinking smokers’ treatment needs and preferences: a mixed-methods study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;59:38-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Motschman CA, Gass JC, Wray JM, et al. Selection criteria limit generalizability of smoking pharmacotherapy studies differentially across clinical trials and laboratory studies: a systematic review on varenicline. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brower KJ. Alcohol’s effects on sleep in alcoholics. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25(2):110-125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patterson F, Jepson C, Strasser AA, et al. Varenicline improves mood and cognition during smoking abstinence. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(2):144-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol