This study aims to determine the appropriateness of tranexamic acid administration by US military medical personnel based on current Joint Trauma System clinical practice guidelines and to determine if tranexamic acid administration is associated with venous thromboembolism.

Key Points

Question

How has the US military used tranexamic acid (TXA) in combat trauma patient care, and has this affected venous thromboembolic events?

Findings

In this cohort study of 455 combat trauma patients, we found that military physicians and first responders have decreased the number of missed doses of TXA but have increased overadministration of TXA. Additionally, TXA administration was an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolic events.

Meaning

Revisiting the clinical practice guidelines and continued education on TXA administration should be undertaken to maximize the benefit of and limit complications from TXA use.

Abstract

Importance

Since publication of the CRASH-2 and MATTERs studies, the US military has included tranexamic acid (TXA) in clinical practice guidelines. While TXA was shown to decrease mortality in trauma patients requiring massive transfusion, improper administration and increased risk of venous thromboembolism remain a concern.

Objective

To determine the appropriateness of TXA administration by US military medical personnel based on current Joint Trauma System clinical practice guidelines and to determine if TXA administration is associated with venous thromboembolism.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study of US military casualties in US military combat support hospitals in Afghanistan and a single US-based tertiary military treatment facility within the continental United States was conducted from 2011 to 2015, with follow-up through initial hospitalization and readmissions.

Exposures

Data collected for all patients included demographic information as well as Injury Severity Score; receipt of blood products, TXA, and/or a massive transfusion; and admission hemodynamics.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Variance from guidelines in TXA administration and venous thromboembolism. Tranexamic acid overuse was defined as a hemodynamically stable patient receiving TXA but not a massive transfusion, underuse was defined as a patient receiving a massive transfusion but not TXA, and TXA administration was considered delayed when given more than 3 hours after injury.

Results

Of the 455 identified patients, 443 (97.4%) were male, and the mean (SD) age was 25.3 (4.8) years. A total of 173 patients (38.0%) received a massive transfusion, and 139 (30.5%) received TXA in theater. Overuse occurred in 18 of 282 patients (6.4%) and underuse in 46 of 173 (26.6%) receiving massive transfusions, and delayed administration was found in 6 of 145 patients (4.3%) receiving TXA. Overuse increased at 3.3% per quarter (95% CI, 4.0-9.9; P < .001; R2 = 0.340) and underuse decreased at −4.4% per quarter (95% CI, −4.5 to −3.6; P < .001; R2 = 0.410). Tranexamic acid administration was an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolism (odds ratio, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.20-5.56; P = .02).

Conclusions and Relevance

Military medical personnel decreased missed opportunities to appropriately use TXA but also increased overuse. In addition, TXA administration was an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolism. A reevaluation of the use of TXA in combat casualties should be undertaken.

Introduction

The use of tranexamic acid (TXA) as a component of massive transfusion protocols has become standard of care for military combat trauma with life-threatening hemorrhage. The initial interest in TXA for trauma followed the publication of the CRASH-2 trial, a randomized placebo-controlled trial that found a reduction in all-cause mortality in trauma patients given TXA. Tranexamic acid gained further attention in military trauma care following the publication of the MATTERs study, which corroborated the results of the CRASH-2 trial with the finding that TXA administration was independently associated with an increase in survival, especially in casualties receiving a massive transfusion (MT), defined as 10 or more units of packed red blood cells within 24 hours.

Subsequent to these publications, the US military’s Joint Trauma System (JTS) incorporated TXA administration into clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), including guidelines for Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC), which apply to care from point of injury through evacuation to surgical care, and recommended the administration of TXA in patients who sustain injury and are likely to require MT. Despite this robust emphasis on TXA for military combat use, there are multiple questions that still surround the use of TXA. For the greatest survival benefit, TXA should be given within the first hour from injury, starting with a 1-g loading dose given over 10 minutes followed by a 1-g infusion over 8 hours. If given after 3 hours from injury, the survival benefit decreases and mortality actually increases. In addition, although TXA administration was not found to independently predict venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the MATTERs study, the presence of these events was statistically higher on univariate analysis in patients who received TXA.

The recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on trauma care stressed data-driven clinical guidelines and process improvement initiatives. With that in mind, the goals of this study are 2-fold. First, given the constraints inherent to medical care in a combat environment, we sought to determine variance from JTS TXA CPG recommendations in a cohort of combat casualties arriving at a military treatment facility in the continental United States. Second, we aimed to determine if TXA was an independent risk factor for VTE in our patient population. We hypothesized that TXA administration varied from JTS recommendations over time and that its use is associated with an increased risk for VTE.

Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

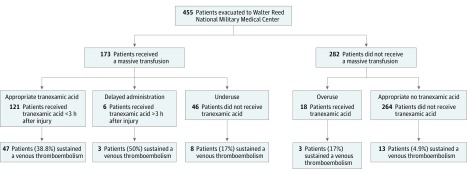

This retrospective study of all combat casualties injured in Iraq or Afghanistan and evacuated to a single continental US military treatment facility between 2011 and 2015 was approved by the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was waived because data were collected from a deidentified database. Data were obtained from the JTS US Department of Defense Trauma Registry for all combat casualties who arrived at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Basic demographic information and clinical characteristics, including 24-hour and total blood product administration, were recorded. Tranexamic acid use and, when possible, timing of administration from point of injury were captured. All medical records were reviewed to determine if casualties sustained a VTE at any point after injury. All cases of VTE in this cohort were defined as computed tomography–confirmed or ultrasonography-confirmed deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolus when the primary team determined treatment was indicated with either anticoagulation or insertion of an inferior vena cava filter. Patients were grouped first based on receipt of MT, then by receipt of TXA, and then by confirmation of VTE (Figure 1). Subgroups were created based on receipt of an MT, defined as receiving 10 or more units of blood products (ie, whole blood, packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, or platelets) in the first 24 hours following injury.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Patients.

Flowchart of patients included in the study and grouping based on variations in tranexamic acid (TXA) administration with venous thromboembolism (VTE) rates for each group.

Appropriateness of TXA administration was assessed for all patients. Tranexamic acid administration was deemed appropriate when a patient received both an MT and TXA within 3 hours of injury or when a patient received neither TXA nor an MT. Deviations from this standard in administration were defined as overuse when a patient received TXA but did not receive an MT, as underuse when a patient received an MT but was not administered TXA, and as delayed administration when TXA was administered to a patient more than 3 hours after injury but did receive an MT.

Data Analysis

The percentage of appropriate TXA administrations for the total patients cared for was calculated for every 3-month period over the course of the study and compared over time. The overuse rate was calculated as the number of overuses divided by the total number of patients cared for each quarter within our data set (ie, overuse rate = number of overuses/total number patients treated). The underuse rate was calculated as the number of underuses divided by the total number of patients cared for each quarter (ie, underuse rate = number of underuses/total number of patients treated). Linear regression was used to assess changes in trends of TXA administration over time, with data points weighted by the total number of patients within the data set in each quarter. Total numbers of overuses and underuses were also calculated for each individual medical treatment facility that patients were initially evacuated to and compared to determine if a single site was responsible for a disproportionate amount of the deviations from CPGs.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between the groups of patients who sustained a VTE vs those who did not were compared using unpaired t test for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was conducted for age, blast exposure (mechanism of injury involving explosion), Injury Severity Score, number of units of blood product in first 24 hours and total in theater, presentation heart rate and blood pressure, presentation hematocrit level, presentation Glasgow Coma Scale score, and TXA administration. Variables that achieved P < .15 were analyzed by multivariate logistic regression. Subgroup analyses of the cohorts of patients who did and did not receive an MT were also conducted in the same manner. All P values were 2-tailed, and significance was set at P < .05. All statistics were performed in STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Demographic Information

We included 455 eligible patients who were treated at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center during the study period. A total of 441 patients (99.1%) survived to discharge. The 4 deaths in our cohort all followed withdrawal of care in patients who experienced severe traumatic brain injuries. One hundred seventy-three casualties (38.0%) received an MT and 145 (31.9%) received a dose of TXA following their injury. Most casualties were male (443 [97.4%]) and US servicemembers on active duty (443 [97.4%]).

Table 1 lists the basic demographic information, clinical characteristics, blood product use, and the occurrence of venous thromboembolic complications for the total cohort and for the subsets of patients who did and did not receive an MT. In general, the patients who received TXA were younger (mean age, 25.2 years vs 27.4 years; P = .001), more likely to have explosion as the mechanism of injury (explosion as mechanism of injury, 77.9% vs 59.0%; P < .001), had higher Injury Severity Scores (mean score, 27.8 vs 15.6; P < .001), received more blood products (mean total blood products, 34.5 units vs 5.2 units; P < .001), and experienced a greater rate of VTE complications (VTE rate, 34.5% vs 6.8%; P < .001).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Data for Overall Cohort and Subgroups Based on Receipt of Tranexamic Acid (TXA).

| Variable | Mean (SD) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 455) | Massive Transfusion (n = 173) | No Massive Transfusion (n = 282) | |||||||

| TXA (n = 146) | No TXA (n = 309) | P Value | TXA (n = 127) | No TXA (n = 46) | P Value | TXA (n = 18) | No TXA (n = 264) | P Value | |

| Demographic data | |||||||||

| Age, y | 25.3 (4.8) | 27.4 (7.1) | .001 | 25.3 (4.9) | 29.0 (8.3) | .001 | 24.7 (3.7) | 27.1 (6.8) | .14 |

| Male, No. (%) | 144 (99.3) | 299 (96.4) | .11 | 126 (99.2) | 45 (98) | .46 | 18 (100) | 254 (96.2) | NA |

| Mechanism of injury | |||||||||

| GSW, No. (%) | 25 (17.1) | 86 (27.8) | <.001 | 20 (15.7) | 13 (28) | .17 | 5 (28) | 73 (27.7) | .91 |

| Explosion, No. (%) | 113 (77.4) | 183 (59.2) | NA | 102 (80.3) | 31 (67) | NA | 11 (61) | 152 (57.6) | NA |

| Other blunt, No. (%) | 6 (4.1) | 41 (13.3) | NA | 5 (3.9) | 2 (4) | NA | 2 (11) | 39 (14.8) | NA |

| ISS | 27.8 (12.4) | 15.6 (10.8) | <.001 | 29.4 (12.2) | 25.9 (9.7) | .08 | 16.8 (6.7) | 13.8 (10.0) | .27 |

| GCS score | 13.2 (3.7) | 14.2 (2.6) | .001 | 13.0 (3.8) | 13.3 (3.7) | .67 | 14.0 (2.8) | 14.4 (2.3) | .52 |

| HR | 120.6 (30.0) | 92.8 (24.4) | <.001 | 123.7 (29.2) | 109.7 (30.3) | .007 | 102.2 (29.6) | 89.7 (22.1) | .02 |

| SBP | 115.5 (30.8) | 131.4 (23.9) | <.001 | 113.3 (29.1) | 117.1 (28.3) | .46 | 132.4 (37.1) | 133.8 (22.3) | .81 |

| Hematocrit level | 38.2 (6.7) | 42.6 (5.4) | <.001 | 37.4 (6.9) | 38.9 (6.2) | .22 | 43.4 (4.3) | 43.3 (4.9) | .96 |

| Blood products | |||||||||

| Total in first 24 h | 34.5 (25.0) | 5.2 (14.5) | <.001 | 38.7 (23.8) | 28.7 (27.3) | .02 | 4.4 (3.2) | 1.1 (2.2) | <.001 |

| PRBC in first 24 h | 13.1 (8.6) | 2.2 (5.0) | <.001 | 14.6.0 (8.1) | 10.6 (8.4) | .006 | 2.6 (2.0) | 0.7 (1.4) | <.001 |

| WB in first 24 h | 1.3 (3.1) | 0.3 (2.0) | <.001 | 1.5 (3.2) | 1.9 (4.8) | .49 | 0 (0) | 0 (0.1) | .71 |

| FFP in first 24 h | 11.6 (7.6) | 1.7 (4.3) | <.001 | 13.1 (7.0) | 8.8 (7.7) | .001 | 1.6 (1.7) | 0.4 (1.0) | <.001 |

| Platelets in first 24 h | 2.0 (1.9) | 0.3 (1.5) | <.001 | 2.2 (1.8) | 2.0 (3.5) | .61 | 0.2 (0.7) | 0 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Cryoprecipitate in first 24 h | 6.5 (9.0) | 0.8 (4.4) | <.001 | 7.4 (9.3) | 5.4 (10.4) | .22 | 0.1 (0.2) | 0 (0.1) | .01 |

| VTE, No. (%) | 50 (34.2) | 21 (6.8) | <.001 | 47 (37.0) | 8 (17) | .02 | 3 (17) | 13 (4.9) | .07 |

| Mortality, No. (%) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (1.0) | >.99 | 1 (0.8) | 2 (4) | .17 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | NA |

Abbreviations: FFP, fresh frozen plasma; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; GSW, gunshot wound; HR, heart rate; ISS, Injury Severity Score; NA, not applicable; PRBC, packed red blood cells; SBP, systolic blood pressure; VTE, venous thromboembolism; WB, fresh whole blood.

Variance in Administration

Tranexamic acid overuse (patients who received TXA and no MT) was found in 18 of 145 patients (12.4%) who received TXA, underuse (patients who received an MT but no TXA) in 46 of 173 patients (26.6%) who received an MT, and delayed administration (TXA given after 3 hours from injury) in 6 of 145 patients (4.1%) who received TXA. Figure 1 displays the breakdown of TXA administration within these different groups. Deviations from the CPG occurred at 17 of 25 included military treatment facilities. Of the 17 locations where this occurred, no location committed a statistically disproportionate number of deviations from the CPG. The overuse cohort received more blood products and had a nonstatistically significant increased rate of VTE (16.7% vs 4.9%; P = .07) compared with patients who did not receive an MT or TXA. In the underuse group, patients who did not receive TXA (but should have based on CPG) were older, had a lower presentation heart rate, received less blood products, and had a lower rate of VTE compared with patients who received an MT and TXA.

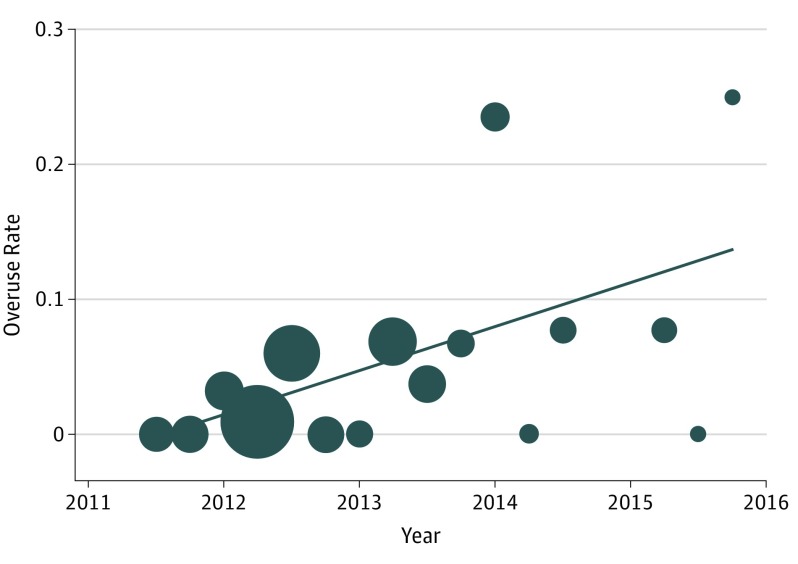

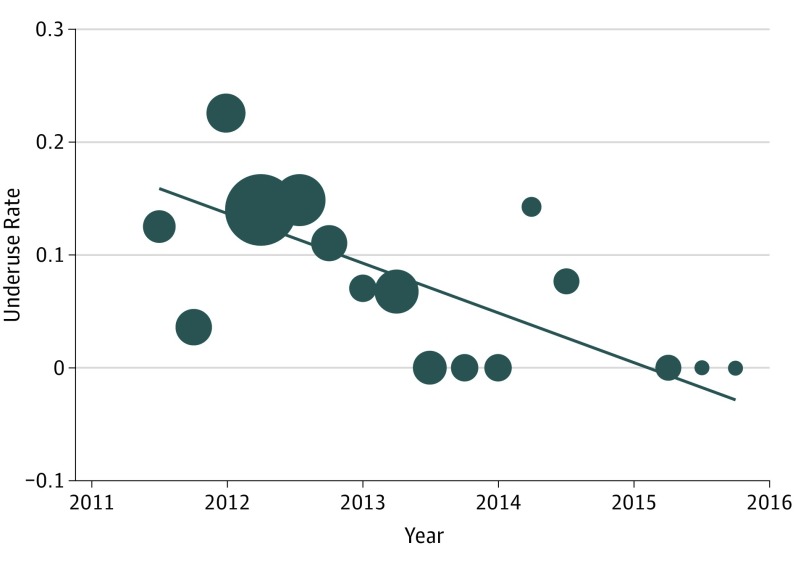

Within the 4.5 years of data included in the study, the mean (range) overuse rate per quarter was 5.4% (range, 0-25.0), and the mean (range) underuse rate per quarter was 6.7% (range, 0-22.6). Figure 2 and Figure 3 display the rates over time for overuse and underuse, respectively. On linear regression, the overuse rate increased at a rate of 3.3% per quarter (95% CI, 4.0-9.9; P < .001; R2 = 0.340), and the underuse rate decreased at a rate of −4.4% per quarter (95% CI, −4.5 to −3.6; P < .001; R2 = 0.410). The overall rate of deviations from the CPG and the delayed administration rate did not change over time.

Figure 2. Changes in Rate of Overuse Over Time.

The rates are calculated as the number of overuses divided by the total number of patients cared for in our cohort within that period. Each data point is weighted by the number of patients cared for during that period; greater size indicates a higher number of patients. The line indicates results of linear regression. The slope of the regression is 0.033x − 65.6; R2 = 0.340.

Figure 3. Changes in Rate of Underuse Over Time.

The rates are calculated as the number of underuses divided by the total number of patients cared for in our cohort within that period. Each data point is weighted by the number of patients cared for during that period; greater size indicates a higher number of patients. The line indicates the results of fitted values. The slope of the fitted values is −0.044x + 89.2; R2 = 0.410.

Thromboembolic Complications

A total of 71 VTE events occurred, for an overall rate of 15.6%. Figure 1 displays the breakdown of VTE among patients who did and did not receive TXA and/or an MT. On logistic regression controlling for variables on univariate analysis with P < .15 (Table 2), TXA administration was found to be an independent risk factor for VTE (odds ratio [OR], 2.58; 95% CI, 1.20-5.56; P = .02). Injury Severity Score was also found on logistic regression to predict VTE (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03-1.09; P < .001).

Table 2. Demographic and Clinical Data for Overall Cohort and Subgroups Based on Occurrence of Venous Thromboembolic Events (VTEs).

| Variable | Mean (SD) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 455) | Massive Transfusion (n = 173) | No Massive Transfusion (n = 282) | |||||||

| VTE (n = 71) | No VTE (n = 384) | P Value | VTE (n = 55) | No VTE (n = 118) | P Value | VTE (n = 16) | No VTE (n = 266) | P Value | |

| Demographic data | |||||||||

| Age, y | 26.3 (5.7) | 26.8 (6.7) | .53 | 26.5 (6.3) | 26.2 (6.2) | .73 | 25.4 (3.3) | 27.1 (6.8) | .33 |

| Male, No. (%) | 69 (97) | 373 (97.1) | >.99 | 54 (98) | 117 (98.2) | .54 | 15 (94) | 257 (96.6) | .45 |

| Mechanism of injury | |||||||||

| Blast exposure, No. (%) | 55 (78) | 241 (62.7) | .02 | 45 (82) | 88 (74.6) | .34 | 10 (63) | 153 (57.5) | .80 |

| ISS | 29.8 (17.6) | 17.6 (11.6) | <.001 | 32.9 (12.1) | 26.4 (10.8) | <.001 | 19.1 (11.4) | 13.7 (9.6) | .03 |

| GCS score | 12.8 (4.0) | 14.1 (2.8) | .002 | 12.4 (4.3) | 13.4 (3.5) | .13 | 14.1 (2.2) | 14.4 (2.3) | .70 |

| HR | 116.9 (29.9) | 98.7 (28.5) | <.001 | 123.9 (27.7) | 118.1 (31.0) | .24 | 92.9 (24.9) | 90.3 (22.7) | .66 |

| SBP | 116.9 (28.4) | 128 (26.7) | .002 | 112.6 (26.8) | 115 (29.8) | .61 | 131.4 (29.5) | 133.8 (23.1) | .68 |

| Presentation hematocrit level | 38.3 (7.9) | 41.7 (5.7) | <.001 | 36.5 (8.1) | 38.4 (6.0) | .09 | 44.0 (3.9) | 43.3 (4.9) | .59 |

| Blood products | |||||||||

| PRBC in first 24 h | 12.3 (10.3) | 4.5 (7.0) | <.001 | 15.4 (9.7) | 12.7 (7.6) | .047 | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.7 (1.1) | .02 |

| WB in first 24 h | 1.4 (3.1) | 0.5 (2.2) | .001 | 1.9 (3.4) | 1.4 (3.8) | .50 | 0 (0) | 0 (0.1) | .73 |

| FFP in first 24 h | 10.7 (8.9) | 3.8 (6.3) | <.001 | 13.5 (8.2) | 11.2 (6.9) | .06 | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.3 (0.9) | .02 |

| Platelets in first 24 h | 1.8 (2.1) | 0.7 (1.7) | <.001 | 2.4 (2.1) | 2.1 (2.5) | .42 | 0 (0) | 0 (0.2) | .71 |

| Cryoprecipitate in first 24 h | 6.5 (10.6) | 1.9 (5.6) | <.001 | 8.3 (11.4) | 6.2 (8.6) | .18 | 0 (0) | 0 (0.1) | .73 |

| TXA administration, No. (%) | 50 (70) | 95 (24.7) | <.001 | 47 (85) | 80 (67.8) | .02 | 3 (19) | 13 (5.2) | .07 |

| TXA administration >3 h from injury, No. (%) | 3 (4) | 3 (0.7) | .051 | 3 (5) | 3 (2.5) | .38 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

Abbreviations: FFP, fresh frozen plasma; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; GSW, gunshot wound; HR, heart rate; ISS, Injury Severity Score; NA, not applicable; PRBC, packed red blood cells; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TXA, tranexamic acid; WB, fresh whole blood.

In the subgroup analysis of the MT cohort, the rate of VTE was 31.8%, and TXA administration was associated with an increased risk for VTE (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.20-6.49; P = .02). In the subgroup that did not receive an MT, the VTE rate was 5.7%, and TXA administration (overuse) was not statically significantly associated with VTE in this group (OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 0.99-15.03; P = .07).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is among the first published studies that have demonstrated TXA administration to be independently associated with VTE in combat casualties. We also found that since the implementation of the CPG, there has been an increased use of TXA in patients not requiring an MT. The application of TXA in this scenario was considered overuse and deemed inappropriate, as these patients were less likely, if at all, to benefit from TXA. This situation likely involved preemptive TXA delivery in patients expected to need an MT but ultimately not requiring one. Given that the current published data does not demonstrate a reduction in blood product transfusion requirements with TXA, we suggest that this was an overuse vs a drug effect of TXA in reducing transfusion requirements. Conversely, our results show that TXA administration was neglected in fewer patients receiving an MT; that is, more patients requiring an MT appropriately received TXA over time. In this setting, not giving TXA was considered an underuse, as mortality is reduced in these patients requiring an MT when TXA is administered.

Our findings suggest that there was adequate dissemination and implementation of the CPG among medical personnel but potential overuse noncompliance with TXA administration. Medication overuse noncompliance is far from unique to combat casualty care, with battles to reduce the overuse of antibiotics and opioids being 2 well-known examples in the medical community. Nonetheless, the variation in drug use we discovered provides an opportunity for increased education with evidence-based medicine to address this issue and underscores the importance of process improvement in light of the increased risk for VTE.

This study was not designed to assess mortality, as almost all patients survived to discharge from our center, and the few deaths that occurred were unrelated to VTE. Consequently, this study does not address or challenge the survival benefit demonstrated in the CRASH-2 and MATTERs publications. The reported survival benefit is credited to the antifibrinolytic properties, as hyperfibrinolysis has been shown to increase mortality in hemorrhaging trauma patients, while the low complication rate (VTE) has been attributed to TXA’s mechanism of preventing thrombus breakdown but not propagating clot formation. However, we demonstrated that VTE is independently associated with TXA administration and caution that adverse consequences may outweigh benefits with inappropriate administration. Further, we suggest that TXA’s antifibrinolytic action may enhance thrombus formation.

The subset analysis of the CRASH-2 trial in which administration of TXA greater than 3 hours after injury was associated with increased mortality previously demonstrated that the benefit of TXA is constrained by a requirement for early administration. This also suggests that the reversal of the hyperfibrinolytic state, reportedly attributed to survival, is limited to the first 3 hours after injury, a finding that remains unexplained. Our data add that the benefits of TXA administration may be further limited by an increased risk for VTE, and we contend that this constraint requires greater discretion in patient selection for TXA administration so that those patients less likely to benefit are not subjected to increased risk.

This study differs from previous studies in its selection of VTE as the primary end point and by studying a patient population at particularly high risk for VTE. Our overall VTE rate of 15.6% is substantially higher than the CRASH-2 and MATTERs studies, which reported rates of VTE of 1.8% and 4.0%, respectively. However, our rate is similar to the incidence others have published for combat casualty studies where VTE was a central focus. The trauma patient is known to be at increased risk for VTE, and the combat trauma patient population subset is at even higher risk. In addition, our cohort was severely injured and required medical evacuation to the US, with prolonged periods of immobility. These factors place our patients at great risk for VTE and may explain our higher event rates. This study further benefited from its access to and review of all inpatient and outpatient medical records, allowing for the best possible capture of all VTE events.

Based on our results, we suggest further investigation into TXA administration for use on combat casualties. Given the current published data regarding the greatest benefit for TXA administration (given within 1 hour of injury and to patients requiring an MT), perhaps TXA should be limited to situations in which a patient is experiencing life-threatening hemorrhage, evidenced by hemodynamic instability, with observed major blood loss, such as with a lower extremity amputation, and the time to damage control surgery is greater than 1 hour after injury. It could be that for maximum benefit, TXA therapy should be individualized and data driven based on thromboelastography results. Further, as a process improvement initiative, the military medical community should be continuously educated on the risks and benefits of TXA, with emphasis on identification of patients who should receive TXA in combat under their care. This should also be reflected in the CPGs to ensure variations in TXA use are minimized or eliminated. Finally, as a medical community, we may be willing to accept some overuse to minimize underuse of TXA, but in general, we would suggest that this is not good practice.

Future research needs to focus on identifying patients who will benefit the most from TXA and who are likely to be at the greatest risk of VTE. Obviously, TXA administration should be limited to the subset of patients who receive the maximum benefit while mitigating the complications in those patients who may be receiving TXA without any added benefit at all. Current evidence suggests that patients receiving MT for traumatic hemorrhage likely have the most to gain from TXA administration; however, this needs to be better defined. Additionally, identifying those patients at greatest risk for VTE will allow for potentially more aggressive prophylaxis or early screening, which could limit complications.

Limitations

There are several limitations that deserve mentioning. This was a retrospective study, so limitations inherent to this type of design must be taken into account. We do not have specific data on the location of TXA administration (prehospital vs in hospital) or any thromboelastography data that may have driven TXA use. The JTS database includes only patients who survived to evacuation to a role 3 or combat support hospital. Consequently, there likely is a survival bias that may influence our results. Further, given the relatively small size, especially of the subgroups, there is a possibility for type II errors. While we attempted to control for confounding with multivariate analysis, the possibility of this occurs in a nonrandomized trial. The subgroup analyses did not identify TXA as an independent association with VTE in either of the cohorts that did and did not receive an MT. This may be because of the small sample sizes and the low number of VTE events within these subgroups.

Conclusions

In our cohort of combat casualties, we found VTE to be a relatively common complication and identified TXA to be an independent risk factor for a VTE event. While military medical teams reduced missed opportunities to administer TXA appropriately in patients receiving an MT, there has been a reciprocal increase in the potential overuse of TXA during the same period. There are limitations to when and where TXA can be given, and there is a need for continual education and training. Careful selection of patients to include field-expedient indications and individualized administration will improve assurance that therapeutic benefit outweighs any potential harm.

References

- 1.Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, et al. ; CRASH-2 trial collaborators . Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison JJ, Dubose JJ, Rasmussen TE, Midwinter MJ. Military application of tranexamic acid in trauma emergency resuscitation (MATTERs) study. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Army Institute of Surgical Research Damage control resuscitation (CPG ID: 18). http://www.usaisr.amedd.army.mil/cpgs/DamageControlResuscitation_03Feb2017.pdf Accessed January 10, 2017.

- 4.National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. Tactical combat casualty care guidelines for medical personnel guidelines and curriculum. http://www.naemt.org/education/TCCC/guidelines_curriculum. Accessed January 10, 2017.

- 5.Roberts I, Shakur H, Afolabi A, et al. ; CRASH-2 collaborators . The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9771):1096-1101, 1101.e1-1101.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berwick D, Downey A, Cornett E, eds. A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ackerman S, Gonzales R. The context of antibiotic overuse. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):211-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renthal W. Seeking balance between pain relief and safety: CDC issues new opioid-prescribing guidelines. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(5):513-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Matthay MA, Mackersie RC, Pittet J-F. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through the protein C pathway? Ann Surg. 2007;245(5):812-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang M, Wierup P, Rea CJ, Ingerslev J, Hjortdal VE, Sørensen B. Temporal changes in clot lysis and clot stability following tranexamic acid in cardiac surgery. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2017;28(4):295-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cap AP, Baer DG, Orman JA, Aden J, Ryan K, Blackbourne LH. Tranexamic acid for trauma patients: a critical review of the literature. J Trauma. 2011;71(1, suppl):S9-S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caruso JD, Elster EA, Rodriguez CJ. Epidural placement does not result in an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism in combat-wounded patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(1):61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paffrath T, Wafaisade A, Lefering R, et al. ; Trauma Registry of DGU . Venous thromboembolism after severe trauma: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Injury. 2010;41(1):97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knudson MM, Gomez D, Haas B, Cohen MJ, Nathens AB. Three thousand seven hundred thirty-eight posttraumatic pulmonary emboli: a new look at an old disease. Ann Surg. 2011;254(4):625-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang R, Rodriguez CJ. Venous thromboembolism among military combat casualties. Current Trauma Reports. 2016;2(1):48-53. doi: 10.1007/s40719-016-0037-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchison TN, Krueger CA, Berry JS, Aden JK, Cohn SM, White CE. Venous thromboembolism during combat operations: a 10-y review. J Surg Res. 2014;187(2):625-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang R, Dorlac GR, Allan PF, Dorlac WC. Intercontinental aeromedical evacuation of patients with traumatic brain injuries during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28(5):E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]