Abstract

Objectives:

The project is aimed to compare the tissue sampling rate and the diagnostic accuracy rate of EUS-FNA using 22G nitinol and reverse bevel-tipped needles.

Subjects and Methods:

This was a prospective, randomized, crossover study in a tertiary academic hospital. All consecutive adult patients undergoing EUS-guided FNA for lesions > 2 cm were recruited. Patients fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria underwent EUS-guided FNA using both needles in sequence. They were randomized on a 1:1 basis to determine whether EUS-FNA would be performed first using the 22G reverse bevel-tipped (ProCore) needle followed by the nitinol needle or vice versa. The patients and the pathologists were blinded to the type of needle used.

Results:

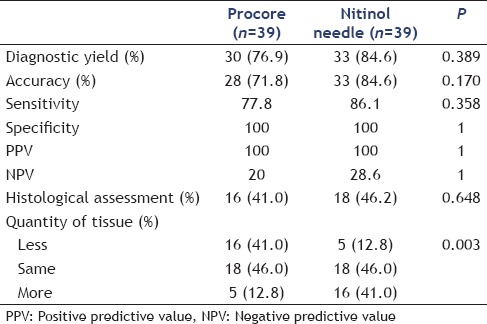

Forty patients with suspected malignant neoplasms were recruited to the study. No significant differences were found in the diagnostic yield (76.9% vs. 84.6%, P = 0.389), accuracy (71.8% vs. 84.6%, P = 0.170), sensitivity (77.8% vs. 86.1%, P = 0.358), specificity (100% vs. 100%, P = 1), positive predictive value (100% vs. 100%, P = 1), and negative predictive value (20.0% vs. 28.6%, P = 1). The percentage of obtained tissue for histological assessment was also similar (41.0% vs. 46.2%, P = 0.648). In terms of the quantity of tissue obtained with the needles, a larger proportion of patients in the nitinol group obtained more tissue for assessment (P = 0.003).

Conclusion:

The tissue-sampling rate and the diagnostic accuracy of the new 22G ProCore needle were comparable to the conventional 22G FNA needle in the absence of an on-site cytopathologist.

Keywords: EUS, FNA, fine-needle biopsy, ProCore

INTRODUCTION

EUS-FNA is a well-established technique for tissue sampling of intestinal and extra-intestinal mass lesions. The accuracy of EUS-guided FNA varies from 60% to 100% with a complication rate of 0% to 3%.[1,2,3] The diagnostic accuracy of the procedure can be improved by the use of immunohistochemical studies and genetic analyses.[4,5] It may also be improved by obtaining a larger biopsy specimen with a core biopsy needle. Recently, two new needles have become available. A 22G needle with a reverse bevel at the tip (EchoTip® ProCore™; Cook Endoscopy, IN, USA) claims to promote the collection of core tissues by shearing material from the target lesion during retrograde movement of the needle in the lesion. The feasibility and safety of this needle have been demonstrated in a recent multicenter, pooled, cohort study.[6] However, the studies comparing this device with conventional needles produced conflicting results, and whether this needle is advantageous over conventional needles is still uncertain. Moreover, another needle made from nitinol (Expect™; Boston Scientific, MA, USA) also has become available. The aim of this study is to compare the tissue-sampling rate and the diagnostic accuracy rate of EUS-FNA using 22G nitinol and the reverse bevel-tipped needles.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This was a prospective, randomized, crossover study. In a tertiary academic hospital, consecutive patients (aged 18–80 years) were recruited and underwent EUS-guided tissue acquisition for evaluating intestinal or extra-intestinal mass lesions measuring >2 cm in the largest diameter. Patients with coagulopathy, a previous history of upper gastrointestinal surgery, contraindications for conscious sedation, those who were pregnant, and those unable to provide informed consent were excluded from the study. Patients fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria underwent EUS-guided FNA using both needles in sequence. They were randomized on a 1:1 basis to determine whether EUS-FNA was to be performed first using the 22G reverse bevel-tipped needle followed by the nitinol needle or vice versa. Patients were randomized by opening sealed opaque envelopes containing computer-generated random sequences in blocks of 10. The patients and the pathologists were blinded to the type of needle used.

Procedures

All patients underwent standard preparations for EUS and were kept nil by mouth for 6 h before the procedure. EUS was performed under conscious sedation with midazolam by one of the investigators (CC, RT, or AT). All the investigators had performed >200 EUS-FNA procedures before participating in this study. A linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT180; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used. Then, the target lesion was visualized and scanned for intervening vessels and EUS-guided FNA was performed with the 22G ProCore needle (ECHO-HD-22-C; Cook Endoscopy, USA) and the 22G conventional needle (Expect™; Boston Scientific, MA, USA). A fanning technique was used during FNA. Suction (10 mL) was routinely applied using a syringe bottle, and the needle was moved to and fro within the lesion 10–15 times. The tissue samples obtained were then expelled into a formalin-based preparation by flushing passage of the stylet through the needle. No on-site cytopathologists were available. Two passes were performed using each needle on the same lesion.

Postprocedural management

All patients were monitored in the ward for any complications for 6 h before discharge and reviewed within 4 weeks for pathology results and late complications.

Histological assessment

All FNA results were interpreted by a single cytopathologist (AC) who was blinded to the randomization result. In addition to the tissue diagnosis, the FNA samples were also evaluated for the presence of an intact histologic core that would be feasible for histological architecture assessment. For each patient, the amount of tissue obtained from the two needles was directly compared.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the diagnostic yield of EUS-guided FNA. Secondary outcomes included sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and diagnostic accuracy. Surgical specimens, when available, were used as the gold standard. When surgical specimens were not available, a positive diagnosis of malignancy by EUS-FNA was accepted as a true positive. When tissue diagnosis was not available, the clinical course of the patient over 1 year was used to determine the nature of the lesion. A benign diagnosis was confirmed by the presence of tissue samples or nonprogressing clinical course at 1 year.

Statistical analysis and sample size estimation

A 30% difference was assumed in the diagnostic yield obtained by EUS-FNA with the two needles in the absence of on-site cytopathology.[3,7,8,9,10,11,12] To give a power of 80% at a Type 1 error of 5%, a total of 39 patients would be required in each group. The primary and secondary outcomes were compared using the Pearson's Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test by intention-to-treat analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

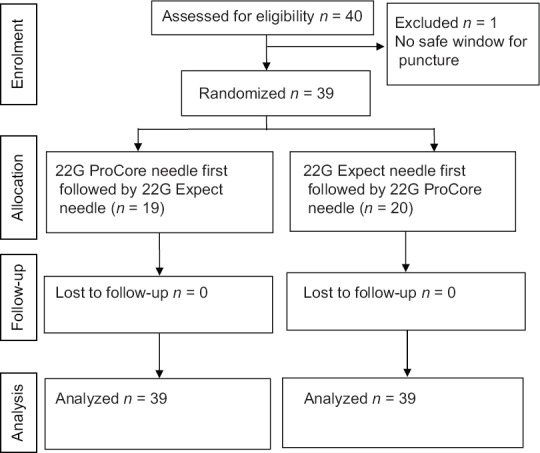

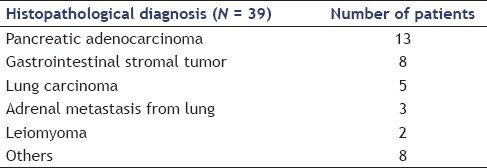

Between July 2012 and February 2014, forty patients with suspected malignant neoplasms were recruited to the study. One patient was excluded from the final analysis, as a safe window for FNA could not be obtained after repeated manipulations. Twenty patients received EUS-FNA with the nitinol needle first and 19 received FNA with the reversed bevel-tipped needle first [Figure 1]. The final diagnoses of the patients are shown in Table 1. Twenty-one patients received FNA through the stomach, nine through the esophagus, and nine through the duodenum. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) size of the lesions was 5.1 (5.3) cm, and the mean (SD) procedure time was 45.4 (17.8) min. None of the 39 patients developed any complications.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram

Table 1.

Final histopathological diagnosis of the patients

The outcomes of the ProCore needle were then compared with those of the nitinol needle [Table 2]. No significant differences occurred in the diagnostic yield (76.9% vs. 84.6%, P = 0.389), accuracy (71.8% vs. 84.6%, P = 0.17), sensitivity (77.8% vs. 86.1%, P = 0.358), specificity (100% vs. 100%, P = 1), PPV (100% vs. 100%, P = 1), and NPV (20.0% vs. 28.6%, P = 1). The percentage of obtained tissue for histological assessment was also similar (41.0% vs. 46.2%, P = 0.648). In terms of the quantity of tissue obtained with the needles, the ProCore and the nitinol needle obtained the same amount of tissue in 18/39 patients, while the nitinol needle obtained more tissue than the ProCore needle in 16/39 patients, which was statistically significant (P = 0.003).

Table 2.

Comparison of outcomes between procore and nitinol needle

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the diagnostic yield of the new 22G ProCore system was comparable to that of the FNA assembly, and the quality of specimen obtained was no better than that procured with the FNA system in the absence of an on-site cytopathologist. However, the yield of histologic core tissue was significantly higher with the Expect™ needle. The technical performance and safety profile of both needles were also comparable.

EUS is a sensitive method for detecting intra- and extra-intestinal pathology, and EUS-guided FNA has a diagnostic accuracy of 60% to 90%.[11,12,13,14] The 22G or 25G EUS-guided FNA needles are preferable for insertion into the target regions if tight angulation is necessary.[15] However, they only allow a limited sample of tissue yielded and potentially reduce diagnostic performance, which leads to repeated procedures and delayed care.[16] Moreover, certain neoplasms such as stromal cell tumors and lymphomas may be difficult to diagnose without histologic samples because their tissue architecture and morphology are essential for accurate pathologic assessment and histochemical study.[17] Therefore, obtaining tissue for histopathology diagnosis in the transduodenal position is always a challenge for endoscopists.[16,18] To circumvent these problems, a new 22G FNA needle with a reverse bevel at the tip was recently developed, though evaluations of this device have been scarce and contradictory.[6,19,20,21]

In the absence of on-site cytopathologists, the possibility of histological assessment and the degree of bloodiness were comparable between the two needles, and there was significantly more tissue obtained with the Expect™ needle. The yield of samples can be increased by a real-time sample adequacy evaluation from an on-site cytopathologist.[22] However, the sensitivity drops by 10% to 15% in the absence of an on-site pathologist to evaluate the cellular adequacy of the samples.[23] Nevertheless, on-site pathologist is not available in many centers because of increased expenses and longer procedure time.[24] The literature shows that fewer passes were required to establish the diagnosis in the fine-needle biopsy (FNB) group than in the FNA group.[21,25] Based on these results, the authors suggested that the FNB device would be especially helpful in hospitals without on-site cytology, as the higher single-pass diagnostic yield of the FNB device may reduce the number of passes required to obtained adequate specimen.[21] Several studies have reported that the combination of EUS-Tru-cut needle biopsy and EUS-FNA affords a higher overall diagnostic yield compared with that achieved using either procedure alone.[16,26] However, our results showed the ProCore device did not offer additional benefit when compared with the conventional one, and the combination of the two needles did not increase the diagnostic yield.

The safety profile of the ProCore was comparable to that of the 22G FNA device. No complication was encountered in the entire cohort. This is in line with an earlier feasibility study evaluating the performance of its 19G counterpart by Iglesias et al., in which none of the 109 patients experienced procedure-related complications.[6] The use of the ProCore needle seems as safe as the conventional FNA needles. The bended endoscope position induces considerable friction within the needle firing mechanism that may impair its proper function. Angulation of the needle within a bended endoscope may result in trapping of the sheath into the reverse bevel. This is a potential complication of this novel needle. However, no such complication was reported in our series of studies. With this novel EUS-FNB histology needle with the reverse bevel, both transgastric and transduodenal puncturing were successful in all cases. Both needles had comparable performance as assessed by endoscopists in terms of needle insertion, emerging from endoscopy, removal of the stylet, and visibility of needle.

One of the advantages of our study was its randomized crossover nature. We performed the EUS-guided puncture with both needles in the same pathology, in a randomized crossover fashion, so that the population bias was minimized. Another advantage was that all samples were examined by a single cytopathologist to avoid interobserver bias.

Our study had several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single center, and the results may not reflect practices or technologies used in other hospitals. Second, an on-site cytopathologist was not available, which may account for the relatively lower diagnostic accuracy. Another limitation was the heterogeneity in pathology. Further studies are required to address the performance of the ProCore needle in a particular pathology.

CONCLUSION

The tissue-sampling rate and the diagnostic accuracy rates of the new 22G ProCore needle were comparable to the conventional 22G FNA needle in the absence of an on-site cytopathologist. Larger trials with cost analysis may be necessary before recommending routine adoption of this device.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gress F, Gottlieb K, Sherman S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of suspected pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:459–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Toole D, Palazzo L, Arotçarena R, et al. Assessment of complications of EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:470–4. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.112839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kida M. Pancreatic masses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalid A, Nodit L, Zahid M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspirate DNA analysis to differentiate malignant and benign pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashida R, Nakata B, Shigekawa M, et al. Gemcitabine sensitivity-related mRNA expression in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:83. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iglesias-Garcia J, Poley JW, Larghi A, et al. Feasibility and yield of a new EUS histology needle: Results from a multicenter, pooled, cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fritscher-Ravens A, Topalidis T, Bobrowski C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in focal pancreatic lesions: A prospective intraindividual comparison of two needle assemblies. Endoscopy. 2001;33:484–90. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-14970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savides TJ, Donohue M, Hunt G, et al. EUS-guided FNA diagnostic yield of malignancy in solid pancreatic masses: A benchmark for quality performance measurement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:277–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ. Endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in the evaluation of pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1386–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, Eltoum IA, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of patients with suspected pancreatic cancer: Diagnostic accuracy and acute and 30-day complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2663–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gress FG, Hawes RH, Savides TJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy using linear array and radial scanning endosonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:243–50. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiersema MJ, Vilmann P, Giovannini M, et al. Endosonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy: Diagnostic accuracy and complication assessment. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1087–95. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawes RH. Endoscopic ultrasound. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2000;10:161–74. viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erickson RA. EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:267–79. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoi T, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, et al. Experimental endoscopy: Objective evaluation of EUS needles. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittmann J, Kocjan G, Sgouros SN, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue sampling by combined fine needle aspiration and trucut needle biopsy: A prospective study. Cytopathology. 2006;17:27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2006.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy MJ, Wiersema MJ. EUS-guided trucut biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:417–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahnschaffe U, Ullrich R, Mayerle J, et al. EUS-guided trucut needle biopsies as first-line diagnostic method for patients with intestinal or extraintestinal mass lesions. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2351–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bang JY, Hebert-Magee S, Trevino J, et al. Randomized trial comparing the 22-gauge aspiration and 22-gauge biopsy needles for EUS-guided sampling of solid pancreatic mass lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanbiervliet G, Napoléon B, Saint Paul MC, et al. Core needle versus standard needle for endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of solid pancreatic masses: A randomized crossover study. Endoscopy. 2014;46:1063–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee YN, Moon JH, Kim HK, et al. Core biopsy needle versus standard aspiration needle for endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling of solid pancreatic masses: A randomized parallel-group study. Endoscopy. 2014;46:1056–62. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iglesias-Garcia J, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Abdulkader I, et al. Influence of on-site cytopathology evaluation on the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of solid pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1705–10. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhala NC, Jhala DN, Chhieng DC, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. A cytopathologist's perspective. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:351–67. doi: 10.1309/MFRF-J0XY-JLN8-NVDP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pellisé Urquiza M, Fernández-Esparrach G, Solé M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: Predictive factors of accurate diagnosis and cost-minimization analysis of on-site pathologist. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;30:319–24. doi: 10.1157/13107565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hucl T, Wee E, Anuradha S, et al. Feasibility and efficiency of a new 22G core needle: A prospective comparison study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:792–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aithal GP, Anagnostopoulos GK, Tam W, et al. EUS-guided tissue sampling: Comparison of “dual sampling” (Trucut biopsy plus FNA) with “sequential sampling” (Trucut biopsy and then FNA as required) Endoscopy. 2007;39:725–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]