Abstract

Background:

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine is a widely used vaccine. Management of local BCG complications differs between clinicians, and the optimal approach remains unclear.

Aims:

We aim to describe the epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects of the BCG vaccine side effects in Sfax.

Patients and Methods:

This was a retrospective study of all the cases of BCG vaccine adverse reactions recorded in the Dermatology and Paediatrics Departments of Hedi Chaker University Hospital of Sfax over a period of 10 years (2005–2015).

Results:

Twenty cases of BCG adverse reactions were notified during the study period. Actually, 80% of the patients presented local adverse reactions. The outcome was good in all the followed patients. The rate of disseminated BCG disease was 20%. Biological tests of immunity showed a primary immunodeficiency in three cases, whereas the outcome was fatal in two cases.

Conclusion:

BCG vaccine adverse reactions range from mild to severe. However, the management of benign local reactions remains unclear. Disseminated BCG disease must alert clinicians to the possibility of a primary immunodeficiency.

Keywords: Adverse reactions, bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine, tuberculosis

What was known?

Local reactions to BCG vaccine include lymphadenitis (mostly involving ipsilateral axillary nodes, rarely supraclavicular, nuchal, or cervical), abscesses, ulceration, and persistent injection-site reactions. There is no Tunisian series exclusively reporting BCG vaccine adverse reactions.

Introduction

Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) is a live attenuated Mycobacterium bovis used as a vaccine against tuberculosis (TB). The type of vaccine administered in our country is M. bovis (French [Pasteur] strain 1173-P2). Specific complications of BCG vaccine are rare.[1] They are often characterised by mild local reactions including lymphadenitis, abscesses, ulceration, and injection site reactions. Their management is still unclear.[2] Serious disseminated forms rarely occur, mainly in immunocompromised children.[3] These complications, however, require intensive therapy. Through this series, we aim to describe the epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic aspects of the BCG vaccine side effects in Sfax (eastern centre of Tunisia).

Patients and Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of all cases of the BCG vaccine adverse reactions recorded in our Dermatology and Paediatrics Departments over a period of 10 years (2005–2015). Inclusion criteria were clinical findings consistent with BCG adverse reactions and/or histopathological features (necrotising granulomas). We collected data about the clinical presentation, laboratory tests, management, and outcome.

Results

Our series included twenty children aged between 7 days and 7 years with an average age of 12.3 months. Boys were more affected than girls with a sex ratio of 1.8:1 Most of them were healthy except for three children (Dandy–Walker syndrome, cerebrovascular thrombosis, and major histocompatibility complex [MHC] class II deficiency). BCG vaccine complications appeared on an average 9.8 months after the vaccination.

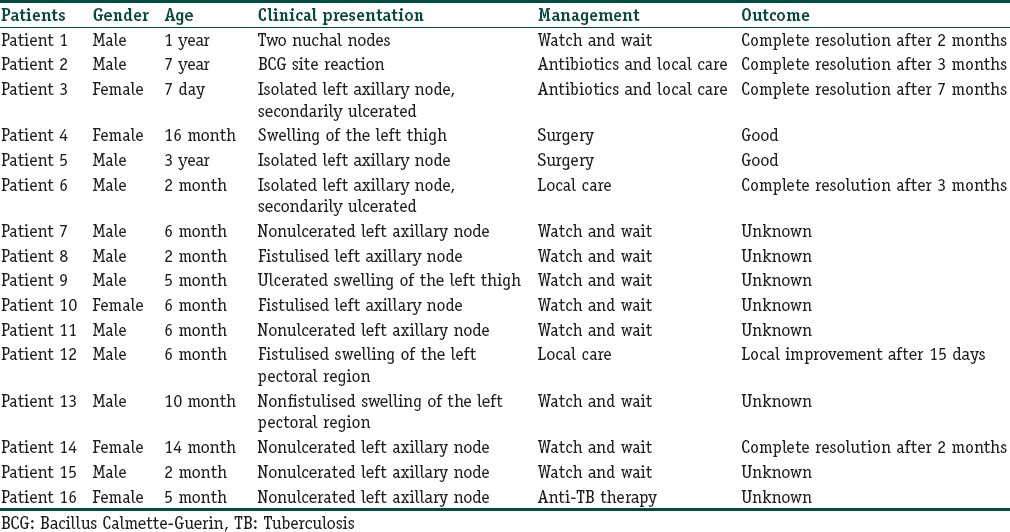

Sixteen children (80%) presented local adverse reactions. Ten of them had lymphadenitis involving left axillary nodes [Figure 1]. Two had swelling of the left pectoral region [Figure 2]. One patient had nuchal nodes, another one had only BCG site reaction, and two patients had aberrant localisation of BCG-induced disease with swelling of the left thigh [Figure 3]. Moreover, fistulisation occurred in six patients. Watch-and-wait attitude was followed in nine cases. Antibiotics and/or local treatment were used in four cases. These measures took care of the problems. Actually, none of the lesions was aspirated (using a needle and a syringe). Surgery was conducted in two cases of nonfistulised lesions. It helped make the diagnosis as pathological examination showed necrotising granulomas. Anti-TB therapy was administered to patient 16 who had MHC class II deficiency [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Local adverse reaction: Fistulised suppurative left axillary lymphadenitis

Figure 2.

Local adverse reaction: Swelling of the left pectoral region

Figure 3.

Local adverse reaction: Swelling of the left thigh on the injection site

Table 1.

Data of patients with local Bacillus Calmette-Guerin adverse reactions

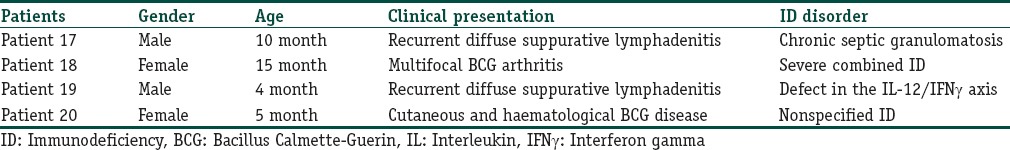

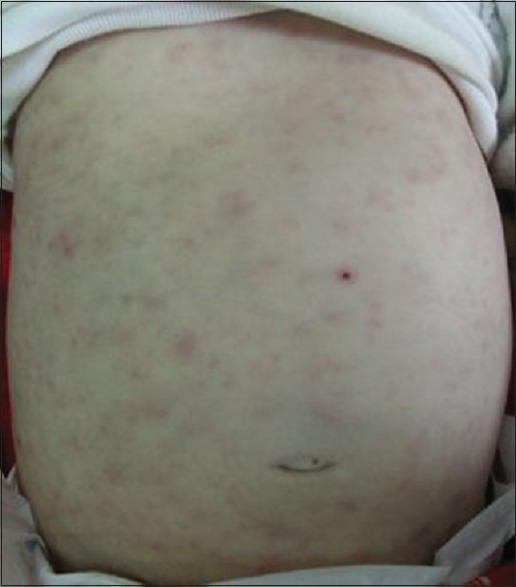

Four children (20%) had disseminated BCG disease [Table 2] with lymphadenopathies, bone, haematological, and/or skin involvement [Figure 4]; fever; and impaired general condition. Bacteriological samples were negative, and probabilistic antibiotics were inefficient. Histology performed in four cases supported the diagnosis of BCG vaccine side effects by showing tuberculoid granuloma with necrosis in three cases. Biological tests of immunity (performed in three cases) showed primary immunodeficiency: chronic septic granulomatosis, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), or defect in the Interleukin-12/Interferon-γ axis. Management consisted of anti-TB therapy. Two of the children died after a septic shock and multi-visceral failure.

Table 2.

Data of patients with disseminated Bacillus Calmette-Guerin disease cases

Figure 4.

Maculopapular rash in a child with disseminated bacillus Calmette–Guerin disease

Discussion

The BCG vaccine was first used in humans in 1921.[2] In countries where TB is endemic like ours, it is recommended for newborns as soon as possible after birth, without booster dose.[4] It protects against pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB. Following the intradermal injection, a granulomatous reaction occurs at the site of inoculation as an expected immunologic response to the Mycobacterium.[1] The systemic spread of BCG is possible, but true symptoms of TB infection are rare. Adverse reactions to BCG vaccine are seen in 1–10% of vaccinees but seem to be underreported.[2] They are usually seen within the first 6 months of vaccination but can occur even 12 months later.[5] A late onset has been reported in five of our patients and reached 7 years in patient 2. Some authors suggested an association between the occurrence of adverse reactions and the type of the injected strain or the type of preparation.[2,6] Compared to weak strains, strong strains, which have a high immunogenicity, are more likely to cause adverse reactions.[7] Other factors, such as the dose of the vaccine, the administration technique, and the underlying immunodeficiency,[8,9] may also increase their frequency. In a Saudi study collecting 145 cases of BCG lymphadenitis, the authors advised to administer the BCG vaccine later after birth as younger children are commonly affected.[10] However, the risk of contamination with Mycobacterium in endemic countries limits delaying of the vaccination.

Local adverse reactions include lymphadenitis (mostly involving ipsilateral axillary nodes like in our series, rarely supraclavicular, nuchal, or cervical), abscesses, ulceration, and persistent injection-site reactions. The diagnosis is clinical. The involvement of the thigh in patients 4 and 9 is uncommon. This may be due to an injection error: by injecting the BCG vaccine into the thigh muscle or by using the same needle when injecting the BCG vaccine and the vitamin K (administered at the same time). A nonsuppurative lymphadenitis may be considered part of the normal course of the BCG vaccination, with a spontaneous resolution within few weeks or months.[11] However, the management of suppurative lymphadenitis still remains controversial.[12] Even if conservative management may be sufficient in some cases, the efficiency of anti-TB therapy is uncertain. Patients with lymphadenitis abscess may need needle aspiration. Local instillation of isoniazid could also shorten the recovery time in these cases.[12] Surgical excision is not recommended as a first-line approach but may be needed after an aspiration failure.[1] Cytohistopathological diagnosis (after aspiration or surgery) is based on the presence of necrotising or non-necrotising granulomas, positive culture for acid- and alcohol-fast bacilli, and/or positive polymerase chain reaction assay.[13,14]

Systemic complications of the BCG vaccine are rare. Actually, their frequency varies across studies from 1% to 17%.[15] Osteitis and osteomyelitis had generally good prognosis and resolved without sequelae.[2] However, disseminated BCG infections are life-threatening complications and often seen in children with primary immunodeficiency, especially SCID. Bernatowska et al suggested diagnostic criteria for disseminated BCG infection in persons with primary immunodeficiency.[15] No guidelines on the treatment for disseminated BCG disease are available. Anti-TB therapies are always useful and were prescribed in all our patients. Treatment of immunodeficiency must always be considered. Mortality rates range from 25% to >70% across studies[15,16] (50% in our series).

It is the first Tunisian series which exclusively reports adverse reactions due to the BCG vaccine. In 2006, Hajlaoui et al registered 12 cases of BCG-specific reactions among 38 Tunisian cases of cutaneous TB over a period of 12 years.[17] Using our hospital study, we are unable to provide an accurate estimate of the overall complication rate associated with the BCG vaccination. However, they seem to be increasing in recent years.

Conclusion

The BCG vaccine complications should be suspected in any BCG vaccine with skin lesions that might have a systemic infection dissemination or antibiotic resistance. Therefore, prompt diagnosis and management are needed, especially in disseminated forms, to avoid serious outcomes. In such situations, clinicians must be aware of the possibility of a primary immunodeficiency, especially SCID. It would be helpful to gather data about the vaccine adverse events, particularly the BCG vaccine, in national or international registries for a better analysis and consequent suitable actions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

We report an uncommon site of BCG adverse reactions involving the thigh. This may be due to an injection error. It is the first Tunisian series which exclusively reports adverse reactions due to the BCG vaccine.

References

- 1.Antaya RJ, Gardner ES, Bettencourt MS, Daines M, Denise Y, Uthaisangsook S, et al. Cutaneous complications of BCG vaccination in infants with immune disorders: Two cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:205–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018003205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venkataraman A, Yusuff M, Liebeschuetz S, Riddell A, Prendergast AJ. Management and outcome of Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine adverse reactions. Vaccine. 2015;33:5470–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conti F, Lugo-Reyes SO, Blancas Galicia L, He J, Aksu G, Borges de Oliveira E, Jr, et al. Mycobacterial disease in patients with chronic granulomatous disease: A retrospective analysis of 71 cases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.041. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health. Republic of Tunisia; 2014. Jul, The vaccination schedule. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teo SS, Smeulders N, Shingadia DV. BCG vaccine-associated suppurative lymphadenitis. Vaccine. 2005;23:2676–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milstien JB, Gibson JJ. Quality control of BCG vaccine by WHO: A review of factors that may influence vaccine effectiveness and safety. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68:93–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norouzi S, Aghamohammadi A, Mamishi S, Rosenzweig SD, Rezaei N. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) complications associated with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Infect. 2012;64:543–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolger T, O’Connell M, Menon A, Butler K. Complications associated with the Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination in Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:594–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.078972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riordan A, Cole T, Broomfield C. Fifteen-minute consultation: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin abscess and lymphadenitis. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2014;99:87–9. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bukhari E, Alzahrani M, Alsubaie S, Alrabiaah A, Alzamil F. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin lymphadenitis: A 6-year experience in two Saudi hospitals. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:202–5. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.97869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuello-García CA, Pérez-Gaxiola G, Jiménez Gutiérrez C. Treating BCG-induced disease in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD008300. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008300.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahmoudi S, Khaheshi S, Pourakbari B, Aghamohammadi A, Keshavarz Valian S, Bahador A, et al. Adverse reactions to Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination against tuberculosis in Iranian children. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2015;4:195–9. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2015.4.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sataynarayana S, Mathur AD, Verma Y, Pradhan S, Bhandari MK. Needle aspiration as a diagnostic tool and therapeutic modality in suppurative lymphadenitis following Bacillus Calmette Guerin vaccination. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002;50:788–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su WJ, Huang CY, Huang CY, Perng RP. Utility of PCR assays for rapid diagnosis of BCG infection in children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:380–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernatowska EA, Wolska-Kusnierz B, Pac M, Kurenko-Deptuch M, Zwolska Z, Casanova JL, et al. Disseminated Bacillus Calmette-Guérin infection and immunodeficiency. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:799–801. doi: 10.3201/eid1305.060865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talbot EA, Perkins MD, Silva SF, Frothingham R. Disseminated Bacille Calmette-Guérin disease after vaccination: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1139–46. doi: 10.1086/513642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajlaoui K, Fazaa B, Zermani R, Zeglaoui F, El Fekib N, Ezzine N, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis. A review of 38 cases. Tunis Med. 2006;84:537–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]