Abstract

The hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES) is a rare group of primary immunodeficiency characterised by recurrent infections, eczema, and elevated serum levels of IgE. Autosomal dominant HIES is caused by mutations in transcription factor – signal transducer and activator of transcription-3. Autosomal-recessive (AR) HIES was described in 2004 due to mutation of tyrosine kinase 2 gene, and subsequently, another mutation in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 gene was discovered in 2009. Although both the forms have many common clinical features, few characteristic findings help in differentiating them. AR-HIES is characterized by recurrent bacterial and viral infections, atopic eczema, and raised serum IgE levels. We report a case of a 4-year-old girl presenting with the features of AR-HIES to highlight the presentation of this rare disease.

Keywords: Autosomal-recessive hyper-IgE syndrome, cutaneous viral infections, dedicator of cytokinesis 8, primary immunodeficiency

What was known?

Hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES) is a rare group of primary immunodeficiency characterised by recurrent infections, eczema, and elevated serum levels of IgE.

Introduction

The hyper-IgE syndromes (HIES) are rare primary immunodeficiencies first described by Deiwis, Schuller, and Wedgewood in 1966.[1] Most cases of HIES are sporadic ones, although autosomal dominant (AD) and recessive inheritance patterns are also seen. Patients usually present with recurrent infections, pneumonias, and raised serum IgE. AD-HIES also known as Job syndrome caused by signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) mutation, is associated with increased risk of recurrent bacterial and fungal infections, along with increased occurrence of pneumonia and pneumatocoeles.[2] Autosomal recessive-HIES (AR-HIES) differs by increased propensity for viral cutaneous infections and more severe atopic eczema.[3] It is mainly caused by tyrosine kinase 2 gene (TYK2) and dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) mutations, mutation in DOCK8 being the commoner one. DOCK8 deficiency has unique presentation such as severe cutaneous viral infections such as warts and molluscum along with increased risk of malignancy at a younger age. TYK2 deficient patients have an unusual presentation of bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) infection.[4] Treatment of these syndromes includes prophylactic antibiotics, genetic counselling, and haematopoietic stem cell transplantation being the last option.

Case Report

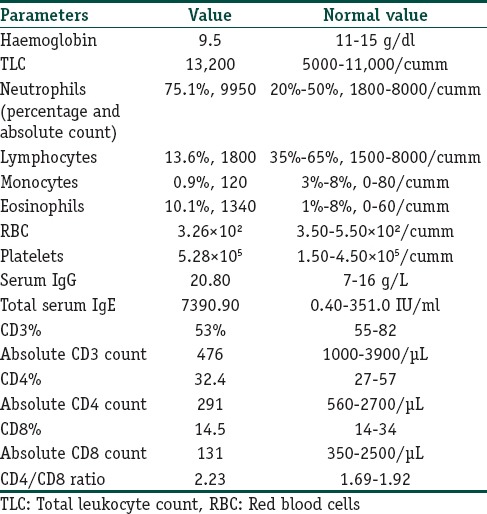

A 4-year-old girl, born to consanguineous parents, presented to our department with atopic eczema and multiple flat warts over trunk along with numerous molluscum contagiosum on the face and perivulval area. She had a history of multiple episodes of pyoderma over scalp which were generalised at times since 1 year of age. She later began to suffer from recurrent episodes of upper and lower respiratory tract infections, recurrent diarrhoea, for which she had been hospitalised twice in the past. Her elder sister had a similar history as that of our index case and she succumbed to severe gastrointestinal infection at the age of 10 years. Dermatological examination revealed eczema over flexures, macerated intertrigo in the groin with perivulval molluscum [Figure 1], and multiple periorbital molluscum with blepharitis [Figure 2]. She also had numerous flat warts over the trunk and hands [Figure 3]. There was no associated lymphadenopathy. Rest of the cutaneous examinations including nails, mucosae, and hair were normal. Systemic examinations were within normal limits. In this context of severe recurring infections, an immune deficiency disease was suspected. The first assessment ruled out HIV infection. The haematological and immunological parameters are summarised in [Table 1]. Significant findings included an elevated serum IgE level, hypereosinophilia, and a low CD4 and CD8 counts. Bone marrow examination ruled out any leukaemic process. Antibodies to cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, and Parvovirus were negative. Both molluscum and viral warts were confirmed by histopathological studies. All these findings suggested primary immunodeficiency as the possible aetiology. Based on the above clinical features and supportive immunological findings, a diagnosis of AR-HIES was made. Since the findings of our case matched to that reported in DOCK8 deficiency patients, the patient most likely had an underlying DOCK8 deficiency. However, genetic confirmation could not be done due to lack of resources in our centre. She was given oral antibiotics and topical corticosteroids for her atopic eczema which improved subsequently. Extraction with curette was done for periorbital molluscum lesions. Parents were counselled regarding the genetic nature of the disease, and she was regularly followed up.

Figure 1.

Multiple pearly white umbilicated papules over perivulval areas

Figure 2.

Multiple periorbital pearly white papules with surrounding erythema and inflammation

Figure 3.

Multiple, flat-topped, small papules over the lower abdomen and dorsum of the right hand

Table 1.

Haematological and immunological parameters

Discussion

The exact genetic aetiologies of HIES remained unknown until 2006. In 2006, a homozygous deletion in Tyk2 was identified in a boy with elevated IgE, eczema, and infections from Japan. This was followed in 2007 with dominant-negative mutations in STAT3 as the aetiology of AD hyper IgE (Job's syndrome). Subsequently, in 2009, homozygous and heterozygous mutations in DOCK8 were identified in a subset of individuals diagnosed with AR-HIES.[5]

Early in the course of the disease, and especially in children, the clinical distinction between the two forms of HIES (recessive and dominant) is difficult because of the similarity of the first symptoms, such as respiratory tract infections, eczema, and skin infections, combined with elevated levels of serum IgE and eosinophilia. Characteristic facial appearance, pneumatocoeles, skeletal abnormalities such as scoliosis and fractures, and delayed shearing of primary teeth are typical to AD-HIES or Job's syndrome, which usually develop late in adolescence.[6] In contrast, AR-HIES due to DOCK8 deficiency exhibits an unusual constellation of clinical features characterised by recurrent cutaneous viral and bacterial infections, extreme eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE without skeletal or dental abnormalities.[3] The cutaneous viral infections, the most striking and distinguishing feature of DOCK8 deficiency, are extensive, difficult to control, and often occur concurrently. The most common virus involved are herpes simplex virus, human papillomavirus, molluscum contagiosum virus, and varicella zoster virus.[7] They also have recurrent infections of the gastrointestinal tract, such as Salmonella enteritis and giardiasis. The manifestations of atopic eczema in AR-HIES are more severe than AD-HIES.[8] Cutaneous malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are more common in such subset. The most striking findings, besides high-serum IgE and eosinophilia, include lymphopenia (affecting both CD4 and CD8 T-cells) and antibody abnormalities.[7] AR-HIES due to tyrosine kinase 2 (Tyk2) mutation has more propensity for mycobacterial pulmonary infections and BCG-osis.[4] There is no specific treatment for HIES. The management should be based on the prevention of infections by bleach baths, topical antiseptics, or antimicrobials to decrease colonisation of Staphylococcus aureus, thereby improving the eczema. The viral infections are most recalcitrant to conventional therapies, with interferon alpha being tried with varying anecdotal success.[9] Given the predisposition of DOCK8-deficient patients to develop skin cancers at an early age, sun protective measures should be emphasised. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation represents a promising therapeutic option for AR-HIES patients, but the potential benefits of improving the severe skin symptoms and correction of the immunodeficiency must be balanced by the risks imparted by additional immunosuppression associated with myeloablation and prophylaxis for graft versus host disease.[8] To the best of our knowledge, only a single case of AR-HIES has been earlier reported from India.[10]

Conclusion

AR-HIES is a rare form of primary immunodeficiency syndrome. Due to the inherent risk of severe life-threatening infections and malignancies, an early diagnosis is essential from therapeutic point of view. Dermatologists can play a crucial role in early identification of the disease due to its cutaneous manifestations.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient had given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understood that her name and initial would not be published and due efforts would be made to conceal her identity, but anonymity could not be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

This case describes the clinical features of a rare disease. Extensive cutaneous viral infections were the predominant finding in our case.

References

- 1.Donabedian H, Gallin JI. The hyperimmunoglobulin E recurrent-infection (Job's) syndrome. A review of the NIH experience and the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983;62:195–208. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minegishi Y, Saito M, Tsuchiya S, Tsuge I, Takada H, Hara T, et al. Dominant-negative mutations in the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 cause hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2007;448:1058–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renner ED, Puck JM, Holland SM, Schmitt M, Weiss M, Frosch M, et al. Autosomal recessive hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome: A distinct disease entity. J Pediatr. 2004;144:93–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(03)00449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woellner C, Schäffer AA, Puck JM, Renner ED, Knebel C, Holland SM, et al. The hyper IgE syndrome and mutations in TYK2. Immunity. 2007;26:535. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman AF, Holland SM. Clinical manifestations of hyper IgE syndromes. Dis Markers. 2010;29:123–30. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woellner C, Gertz EM, Schäffer AA, Lagos M, Perro M, Glocker EO, et al. Mutations in STAT3 and diagnostic guidelines for hyper-IgE syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:424–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su HC. Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) deficiency. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:515–20. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833fd718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, Cowen EW, Davis J, Su HC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79–84. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, Freeman AF, Jing H, Favreau AJ, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kharkar V, Kardekar S, Gutte R, Mahajan S, Thakkar V, Khopkar U, et al. Disseminated molluscum contagiosum infection in a hyper IgE syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:371–4. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.95464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]