Key Points

Question

Is there an association between the dependent coverage provision of the Affordable Care Act (which allowed adults to stay on their parents’ insurance plans until age 26) and payment for birth, prenatal care, and birth outcomes?

Findings

In this study of nearly 3 million births, the dependent coverage provision was associated with increased private insurance payment for birth (1.9 percentage point), increased early prenatal care (1.0 percentage points), increased adequate prenatal care (0.4 percentage points), and a reduction in preterm births (−0.2 percentage points), but not associated with changes in cesarean delivery, low birth weight, or neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Meaning

Allowing young adults to stay on their parent’s insurance was associated with increased private payment for birth, increased prenatal care use, and modest reduction in preterm births.

Abstract

Importance

The effect of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) dependent coverage provision on pregnancy-related health care and health outcomes is unknown.

Objective

To determine whether the dependent coverage provision was associated with changes in payment for birth, prenatal care, and birth outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study, using a differences-in-differences analysis of individual-level birth certificate data comparing live births among US women aged 24 to 25 years (exposure group) and women aged 27 to 28 years (control group) before (2009) and after (2011-2013) enactment of the dependent coverage provision. Results were stratified by marital status.

Main Exposures

The dependent coverage provision of the ACA, which allowed young adults to stay on their parent’s health insurance until age 26 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes were payment source for birth, early prenatal care (first visit in first trimester), and adequate prenatal care (a first trimester visit and 80% of expected visits). Secondary outcomes were cesarean delivery, premature birth, low birth weight, and infant neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Results

The study population included 1 379 005 births among women aged 24-25 years (exposure group; 299 024 in 2009; 1 079 981 in 2011-2013), and 1 551 192 births among women aged 27-28 years (control group; 325 564 in 2009; 1 225 628 in 2011-2013). From 2011-2013, compared with 2009, private insurance payment for births increased in the exposure group (36.9% to 35.9% [difference, −1.0%]) compared with the control group (52.4% to 51.1% [difference, −1.3%]), adjusted difference-in-differences, 1.9 percentage points (95% CI, 1.6 to 2.1). Medicaid payment decreased in the exposure group (51.6% to 53.6% [difference, 2.0%]) compared with the control group (37.4% to 39.4% [difference, 1.9%]), adjusted difference-in-differences, −1.4 percentage points (95% CI, −1.7 to −1.2). Self-payment for births decreased in the exposure group (5.2% to 4.3% [difference, −0.9%]) compared with the control group (4.9% to 4.3% [difference, −0.5%]), adjusted difference-in-differences, −0.3 percentage points (95% CI, −0.4 to −0.1). Early prenatal care increased from 70% to 71.6% (difference, 1.6%) in the exposure group and from 75.7% to 76.8% (difference, 0.6%) in the control group (adjusted difference-in-differences, 0.6 percentage points [95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8]). Adequate prenatal care increased from 73.5% to 74.8% (difference, 1.3%) in the exposure group and from 77.5% to 78.8% (difference, 1.3%) in the control group (adjusted difference-in-differences, 0.4 percentage points [95% CI, 0.2 to 0.6]). Preterm birth decreased from 9.4% to 9.1% in the exposure group (difference, −0.3%) and from 9.1% to 8.9% in the control group (difference, −0.2%) (adjusted difference-in-differences, −0.2 percentage points (95% CI, −0.3 to −0.03). Overall, there were no significant changes in low birth weight, NICU admission, or cesarean delivery. In stratified analyses, changes in payment for birth, prenatal care, and preterm birth were concentrated among unmarried women.

Results

The study population included 1 379 005 births among women aged 24 to 25 years (exposure: 299 024 in 2009; 1 079 981 in 2011-2013), and 1 551 192 births among women aged 27 to 28 years (control: 325 564 in 2009; 1 225 628 in 2011-2013). From 2011-2013, compared with 2009, private insurance payment for births increased in the exposure group vs the control group; Medicaid payment and self-payment decreased. Early and adequate prenatal care increased and preterm birth decreased. There were no significant changes in low birth weight, NICU admission, or cesarean delivery. In stratified analyses, changes in payment for birth, prenatal care, and preterm birth were concentrated among unmarried women.

| Outcome | Women Aged 24-25 y (Exposure), % | Women Aged 27-28 y (Control), % | Adjusted Difference-in-Differences (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepolicy | Postpolicy | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI) | Prepolicy | Postpolicy | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI) | ||

| Payment | |||||||

| Private | 36.9 | 35.9 | −1.0 (−1.2 to −0.8) |

52.4 | 51.1 | −1.3 (−1.5 to −1.1) |

1.9 (1.6 to 2.1) |

| Medicaid | 51.6 | 53.6 | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.2) |

37.4 | 39.4 | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.1) |

−1.4 (−1.7 to −1.2) |

| Self-pay | 5.2 | 4.3 | −0.9 (−0.9 to −0.8) |

4.9 | 4.3 | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.4) |

−0.3 (−0.4 to −0.1) |

| Early prenatal care | 70.0 | 71.6 | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) |

75.7 | 76.8 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) |

1.0 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Adequate prenatal care | 73.5 | 74.8 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) |

77.5 | 78.8 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.4) |

0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) |

| Preterm birth | 9.4 | 9.1 | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) |

9.1 | 8.9 | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) |

−0.2 (−0.3 to −0.03) |

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study of nearly 3 million births among women aged 24 to 25 years vs those aged 27 to 28 years, the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage provision was associated with increased private insurance payment for birth, increased use of prenatal care, and modest reduction in preterm births, but was not associated with changes in cesarean delivery rates, low birth weight, or NICU admission.

This study determines whether the dependent coverage provision of the Affordable Care Act was associated with changes in payment for birth, prenatal care, and birth outcomes among married and unmarried women.

Introduction

Beginning in September 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required private health insurers to allow young adults to remain on a parent’s plan until their 26th birthday. Nearly one-third of US births are to women in the age range affected by the policy (age 19-25 years). Although studies have found that this dependent coverage provision expanded insurance, increased preventive care, and improved self-reported health among young adults, little attention has been given to the effect of the provision on pregnant women. The only study among pregnant women found that the policy was associated with an increase in privately insured births and a decrease in Medicaid-paid births, concentrated among unmarried women.

Insurance changes among reproductive-age and pregnant women associated with the provision could lead to improvements in prenatal care use and birth outcomes (eFigure in the Supplement). Compared with women who are insured prior to pregnancy, uninsured women who become eligible for pregnancy-related Medicaid may face delays accessing prenatal care because of late pregnancy recognition, enrollment barriers, and difficulty finding a clinician. Coverage before pregnancy is associated with earlier initiation of prenatal care, which is associated with reduced adverse outcomes such as prematurity and neonatal death. Expansion of coverage to reproductive-age women may also improve outcomes by increasing access to care before conception, in turn potentially improving chronic disease management, reducing tobacco use, increasing access to contraception, and improving quality and continuity of care.

The objective of this study was to investigate whether the dependent coverage provision’s expansion of health insurance was associated with changes in payment for birth, prenatal care, and birth outcomes among married and unmarried women.

Methods

Data

We used individual-level data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention public-use natality files, which contain a census of US birth certificate data. We limited our sample to states that had adopted the 2003 revised US Standard Certificate of Live Birth format in each year because this format contains consistent outcome definitions and information on payment for birth. Birth certificate data are entered by the birth facility based on clinical records and maternal surveys. During our study period, the number of states using the 2003 format increased from 28 in 2009 to 41 (including Washington, DC) by 2013, but the public data set does not identify individual states over time. This study was deemed non–human subjects research by the Harvard University institutional review board.

Study Design

Similar to previous evaluations of the dependent coverage provision, we conducted a retrospective cohort study analyzed using a difference-in-differences analysis comparing younger adults eligible for the provision to a control group of slightly older adults. We stratified our results by marital status because marriage has the potential to modify the effect of the policy. Married women are more likely to have private insurance than unmarried women (due partly to spousal insurance), decreasing the probability that they will receive coverage through a parent’s plan. This hypothesis is supported by previous research on the dependent coverage provision, including a study on payment for birth, which found larger increases in private insurance among unmarried women.

The study period was 2009-2013 because our data set only included the source of payment for delivery starting in 2009, and, in 2014, the ACA’s Medicaid and marketplace expansions took effect, changing coverage options for all ages. Although dependent coverage was not mandated until September 23, 2010, some insurers voluntarily implemented it earlier in 2010. Accordingly, we excluded births in 2010 as a “washout period,” similar to several prior studies. We classified 2011-2013 as the postpolicy period.

Main Exposure

The primary assumption of difference-in-differences analysis is that the trends observed in the control group are a valid counterfactual for what would have occurred in the exposure group if not for the policy. Following published best practices for this study design, we inspected prepolicy trends before conducting the assessment of the policy’s effects to select our comparison groups. Based on an analysis of monthly trends in our study outcomes before 2010, we defined the exposure group as births to women aged 24 to 25 years and the control group as births to women aged 27 to 28 years. Although many studies of this provision used broader age groups (eg, ages 19-25 years and 27-34 years), such wide age bands may yield less-appropriate comparison groups, and, in our case, violated the parallel trends assumption for primary payment outcomes; thus, we chose narrower age bands for a more appropriate analytical comparison (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Prepolicy monthly trends were more similar within marital strata than for the overall sample (eTable 2 in the Supplement). We detected small but significant differential linear trends prior to 2010 for early prenatal care and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission overall and among unmarried women only (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Estimating our primary difference-in-differences regression as if the policy took effect in July 2009 (post hoc placebo testing), we identified a similar pattern, with significant results for early prenatal care and NICU admission overall and among unmarried women only (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Outcomes

Consistent with numerous studies of health insurance expansions, including the dependent coverage provision, we examined outcomes in 3 domains: insurance status, access to care, and health. This approach is supported by evidence from a variety of settings showing that coverage changes can lead to changes in utilization and health outcomes.

As a proxy for insurance status, we analyzed payment for birth—Medicaid, private insurance, or self-pay. Payment for birth does not necessarily capture coverage status before and during pregnancy; however, most women with private insurance at delivery have it throughout pregnancy, unlike Medicaid, which is often acquired during pregnancy or at delivery. To measure access to care, we examined early prenatal care (first prenatal visit in the first trimester) and adequate prenatal care (defined by the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization [APNCU] index). The APNCU index defines adequate prenatal care as having a visit in the first trimester and at least 80% of the expected number of visits based on gestational age and clinical guidelines. In addition, we selected a set of secondary infant birth outcomes for which previous research suggests an association with insurance status and prenatal care: cesarean delivery, preterm birth (<37 weeks), low birth weight (<2500 g), and infant NICU admission.

Statistical Analysis

We fitted linear probability models for each outcome as a function of exposure group status, status after implementation (2011-2013), and their interaction (eMethods in the Supplement). The interaction term is the difference-in-differences estimate of the association between the provision and the outcome (ie, the differential change before and after the dependent coverage provision among women aged 24-25 years compared with those aged 27-28 years). We used robust standard errors, but also conducted a sensitivity analysis with standard errors clustered at the age group–month level, and this did not substantively change our results (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Multivariable models controlled for potential confounders, including month of delivery; maternal marital status, age, race, ethnicity, and education; whether the birth was a woman’s first live birth; multiple delivery; and paternal age. Race/ethnicity data were drawn from birth certificate data; states typically use this information to track population-level health and disparities. Because private health insurance rates are correlated with employment rates, which could differentially affect the exposure and control groups, we also adjusted for monthly sex-specific and age-specific unemployment rates. Prenatal health behaviors, such as tobacco use, are potentially both intermediate outcomes and confounders (eFigure in the Supplement). Thus, we estimated our main model by both adjusting and not adjusting for tobacco use and found that the results were essentially unchanged (eTable 5 in the Supplement). To assess whether changes in the outcomes were potentially accounted for by changes in payment for birth, we conducted a sensitivity analysis estimating the association between the provision and prenatal care and birth outcomes adjusting for payment for birth. However, our approach did not include a formal causal medication analysis; rather, like numerous published studies of this provision and other recent insurance expansions, we used a difference-in-differences framework to simultaneously assess changes in multiple domains—coverage, access to care, and health outcomes.

Observations with missing or unreported covariates were included in the analysis and coded using an indicator variable for observations in which the covariate was not reported. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons and thus our results should be considered exploratory. A 2-sided P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp), version 13.1.

Results

Study Population

The final sample included 1 379 005 births to women aged 24 to 25 years (exposure group) and 1 551 192 births to women aged 27 to 28 years (control group). Prior to the policy, compared with the control group, the exposure group had a younger paternal age and a higher proportion of women who were Hispanic, black, unmarried, or without postsecondary education (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics Before and After the ACA Dependent Coverage Provision Among Women Aged 24 to 25 Years (Exposure Group) and Women Aged 27 to 28 Years (Control Group)a.

| Characteristic | Women Aged 24-25 y (Exposure Group), % (95% CI) | Women Aged 27-28 y (Control Group), % (95% CI) | Differential Change Exposure Minus Control (95% CI), Percentage Pointsb | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepolicy | Postpolicy | Prepolicy | Postpolicy | |||

| Total births, No. | 299 024 | 1 079 981 | 325 564 | 1 225 628 | ||

| Mean maternal age, y | 24.5 (24.5 to 24.5) | 24.5 (24.5 to 24.5) | 27.5 (27.5 to 27.5) | 27.5 (27.5 to 27.5) | 0.02 (−0.3 to 0.3) | .89 |

| Married | 54.4 (54.2 to 54.6) | 51.2 (51.1 to 51.3) | 68.7 (68.6 to 68.9) | 67.9 (67.8 to 67.9) | −2.3 (−2.6 to −2.0) | <.001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 29.6 (29.4 to 29.7) | 25.2 (25.2 to 25.3) | 26.3 (26.1 to 26.4) | 21.9 (21.9 to 22.0) | 0.03 (−0.2 to 0.3) | .84 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 79.6 (79.4 to 79.7) | 76.5 (76.5 to 76.6) | 80.2 (80.1 to 80.4) | 78.8 (78.7 to 78.8) | −1.6 (−1.8 to −1.4) | <.001 |

| Black | 15.1 (14.9 to 15.2) | 18.0 (17.9 to 18.0) | 12.5 (12.4 to 12.6) | 13.7 (13.6 to 13.8) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | <.001 |

| Otherc | 5.3 (5.3 to 5.4) | 5.5 (5.5 to 5.5) | 7.3 (7.2 to 7.4) | 7.5 (7.5 to 7.6) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.04) | .15 |

| Education | ||||||

| < High school | 19.9 (19.8 to 20.0) | 16.6 (16.6 to 16.7) | 15.7 (15.5 to 15.8) | 12.7 (12.6 to 12.7) | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.1) | .01 |

| High school | 58.2 (58.0 to 58.4) | 59.9 (59.8 to 60.0) | 45.6 (45.4 to 45.8) | 45.0 (44.9 to 45.1) | 2.3 (2.1 to 2.6) | <.001 |

| Any postsecondary | 21.9 (21.8 to 22.1) | 23.4 (23.3 to 23.5) | 38.8 (38.6 to 38.9) | 42.3 (42.2 to 42.4) | −2.1 (−2.3 to −1.8) | <.001 |

| First live birth | 41.5 (41.3 to 41.7) | 42.2 (42.1 to 42.3) | 37.6 (37.4 to 37.7) | 39.4 (39.3 to 39.5) | −1.1 (−1.4 to −0.8) | <.001 |

| Multiple delivery | 2.7 (2.7 to 2.8) | 2.7 (2.6 to 2.7) | 3.2 (3.2 to 3.3) | 3.2 (3.2 to 3.3) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.003) | .06 |

| Mean paternal age, y | 27.7 (27.7 to 27.7) | 27.7 (27.7 to 27.7) | 30.3 (30.2 to 30.3) | 30.3 (30.3 to 30.3) | −0.03 (−0.1 to −0.001) | .04 |

Abbreviation: ACA, Affordable Care Act.

Estimates are based on an unadjusted model with robust standard errors analyzing data before the ACA policy (2009) and after the ACA policy (2011-2013) excluding 2010 as the ACA policy implementation period.

Differential change represents the difference in the change in each characteristic from prepolicy to after policy implementation in the exposure group relative to the control group (eg, the mean maternal age increased by 0.02 more years in the exposure group relative to the control group).

Other indicates a reported maternal race other than white or black.

Payment for Birth

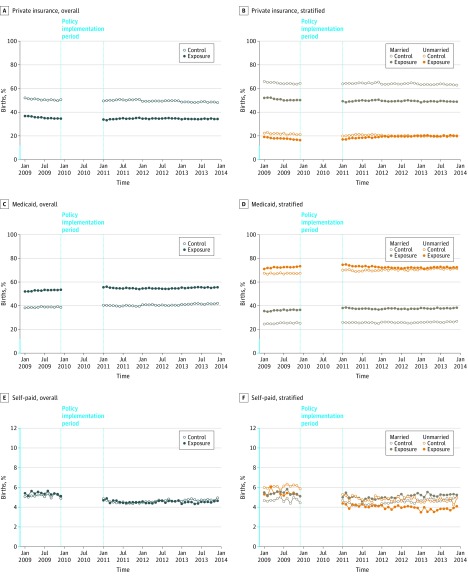

In unadjusted analyses, private insurance payment for births decreased from 36.9% in 2009 to 35.9% in 2011-2013 (difference, −1.0%) among the exposure group and decreased from 52.4% to 51.1% (difference, −1.3%) among the control group (unadjusted difference-in-differences, 0.3 percentage points [95% CI, 0.01 to 0.6]) (Figure and Table 2). Medicaid payment increased from 51.6% to 53.6% (difference, 2.0%) in the exposure group and from 37.4% to 39.4% (difference, 1.9%) in the control group (unadjusted difference-in-differences, 0.1 percentage points [95% CI, −0.2 to 0.4]). Self-payment for births decreased 5.2% to 4.3% (difference, −0.9%) in the exposure group and 4.9% to 4.3% (difference, −0.5%) in the control group (unadjusted difference-in-differences, −0.3 percentage points [95% CI, −0.5 to −0.2]).

Figure. Seasonally Adjusted Primary Source of Payment for Birth for Women Aged 24 to 25 Years (Exposure Group) and Women Aged 27 to 28 Years (Control Group) Overall and by Marital Status.

The y-axis scale shown in blue indicates range from 0% to 12%. The policy implementation period (January 2010-December 2010) was excluded from the analysis. Linear regression modeling of the individual-level data with the payment type as the outcome was used to calculate the monthly season adjustments as coefficients on monthly dummy variables. The seasonal adjustments were subtracted from means calculated at the group and month level. The median No. of births per month (prepolicy/postpolicy): overall control group (27 251/34 139), overall exposure group (24 864/29 861), married control group (18 813/23 136), married exposure group (13 539/15 298), unmarried control goup (8432/10 973), unmarried exposure group (11 361/14 674).

Table 2. Estimated Changes in Pregnancy-Related Outcomes Associated With the ACA Dependent Coverage Provisiona.

| Outcome | Women Aged 24-25 y (Exposure), % | Women Aged 27-28 y (Control), % | Unadjusted Difference-in-Differences Estimate (95% CI), Percentage Points | P Value | Adjusted Difference-in-Differences Estimate (95% CI), Percentage Pointsb | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepolicy (n = 299 024) | Postpolicy (n = 1 079 981) | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI), Percentage Points | Prepolicy (n = 325 564) | Postpolicy (n = 1 225 628) | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI), Percentage Points | |||||

| Payment for birth | ||||||||||

| Private | 36.9 | 35.9 | −1.0 (−1.2 to −0.8) | 52.4 | 51.1 | −1.3 (−1.5 to −1.1) | 0.3 (0.01 to 0.6) | .05 | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.1) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 51.6 | 53.6 | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.2) | 37.4 | 39.4 | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.1) | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.4) | .50 | −1.4 (−1.7 to −1.2) | <.001 |

| Self-pay | 5.2 | 4.3 | −0.9 (−0.9 to −0.8) | 4.9 | 4.3 | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.4) | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.2) | <.001 | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.1) | <.001 |

| Prenatal care | ||||||||||

| Early prenatal carec | 70.0 | 71.6 | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | 75.7 | 76.8 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.8) | <.001 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.2) | <.001 |

| Adequate prenatal cared | 73.5 | 74.8 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 77.5 | 78.8 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.4) | 0.04 (−0.2 to 0.3) | .74 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) | <.001 |

| Birth outcomes | ||||||||||

| Cesarean delivery | 30.1 | 29.7 | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2) | 32.1 | 31.5 | −0.6 (−0.8 to −0.4) | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.4) | .17 | 0.005 (−0.3 to 0.3) | .97 |

| Preterm birth | 9.4 | 9.1 | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) | 9.1 | 8.9 | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.04) | .15 | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.03) | .02 |

| Low birth weighte | 7.5 | 7.6 | 0.1 (−0.03 to 0.2) | 7.2 | 7.2 | −0.005 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.2) | .30 | −0.01 (−0.1 to 0.1) | .91 |

| NICU admission | 6.7 | 7.3 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 6.6 | 7.3 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.1) | .39 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.3) | .11 |

Abbreviation: ACA, Affordable Care Act.

All models analyze data from 2009-2013 excluding 2010 as the ACA policy implementation period and use robust standard errors.

Adjusted models are adjusted for month of delivery; a monthly linear time trend; maternal marital status, age, race, ethnicity, and education; whether the birth was a woman’s first live birth; multiple delivery; paternal age; and monthly unemployment rates.

Early prenatal care is defined as having the first prenatal visit in the first trimester (0-3 mo).

Adequate prenatal care is defined by the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization index.

Low birth weight is defined as birth weight of an infant of less than 2500 g.

In the adjusted difference-in-difference analyses, the dependent coverage provision was associated with a 1.9 percentage-point increase (95% CI, 1.6 to 2.1) in private insurance payment for birth (P < .001; 5% relative increase from a baseline of 37%), a 1.4 percentage-point decrease (95% CI, −1.7 to −1.2) in Medicaid payment (P < .001; 3% relative decrease from a baseline of 52%), and a 0.3 percentage-point decrease (95% CI, −0.4 to −0.1) in self-payment or uninsured (P < .001; 6% relative decrease from a baseline of 5%).

Among unmarried women, the provision was associated with a 3.8 percentage-point increase (95% CI, 3.5 to 4.2) in private insurance (P < .001; 20% relative increase from a baseline of 19%), as well as a 3.6 percentage-point decrease (95% CI, −4.0 to −3.2) in Medicaid (P < .001; 5% relative decrease from a baseline of 71%) (Table 3). The provision was not associated with significant changes in source of payment for married women. The differential changes in private payment (−4.2 percentage points [95% CI, −4.6 to −3.7]; P < .001) and Medicaid payment (3.8 percentage points [95% CI, 3.3 to 4.3]; P < .001) between unmarried and married women were statistically significant.

Table 3. Estimated Changes in Pregnancy-Related Outcomes Associated With the ACA Dependent Coverage Provision, Stratified by Marital Statusa.

| Outcome | Women Aged 24-25 y (Exposure), % | Women Aged 27-28 y (Control), % | Unadjusted Difference-in-Differences Estimate (95% CI), Percentage Points | P Value | Adjusted Difference-in-Differences Estimate (95% CI), Percentage Pointsb | P Value | Adjusted Difference Married Minus Unmarried (95% CI), Percentage Pointsb,c | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepolicy | Postpolicy | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI) | Prepolicy | Postpolicy | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI) | |||||||

| Unmarried Women (n = 1 159 420) | ||||||||||||

| Women, No. | 136 407 | 527 238 | 101 776 | 393 999 | ||||||||

| Payment for birth | ||||||||||||

| Private | 18.9 | 20.5 | 1.7 (1.4 to 1.9) | 22.6 | 21.0 | −1.6 (−1.9 to −1.3) | 3.2 (2.9 to 3.6) | <.001 | 3.8 (3.5 to 4.2) | <.001 | ||

| Medicaid | 71.2 | 71.4 | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) | 66.9 | 70.1 | 3.2 (2.9 to 3.6) | −3.0 (−3.5 to −2.6) | <.001 | −3.6 (−4.0 to −3.2) | <.001 | ||

| Self-pay | 5.1 | 3.7 | −1.4 (−1.5 to −1.3) | 5.7 | 4.4 | −1.3 (−1.4 to −1.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | .19 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | .17 | ||

| Prenatal care | ||||||||||||

| Early prenatal cared | 63.5 | 66.3 | 2.8 (2.5 to 3.1) | 65.3 | 67.5 | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.5) | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.1) | .01 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.3) | <.001 | ||

| Adequate prenatal caree | 68.4 | 70.5 | 2.1 (1.8 to 2.4) | 69.9 | 71.6 | 1.7 (1.4 to 2) | 0.4 (−0.04 to 0.8) | .08 | 0.6 (0.1 to 1.0) | .01 | ||

| Birth outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Cesarean delivery | 31.9 | 31.7 | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) | 34.0 | 34.3 | 0.3 (−0.02 to 0.6) | −0.5 (−0.9 to −0.1) | .02 | −0.6 (−1.1 to −0.2) | <.01 | ||

| Preterm birth | 10.3 | 10.1 | −0.2 (−0.4 to −0.03) | 10.7 | 10.6 | −0.04 (−0.3 to 0.2) | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0.1) | .24 | −0.3 (−0.5,0.002) | .05 | ||

| Low birth weight | 8.8 | 9.0 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | 9.1 | 9.1 | 0.05 (−0.1 to 0.2) | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.4) | .19 | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.3) | .63 | ||

| NICU admission | 7.4 | 8.2 | 0.8 (0.7 to 1) | 7.6 | 8.7 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0.1) | .14 | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.01) | .06 | ||

| Married Women (n = 1 770 777) | ||||||||||||

| Women, No. | 162 617 | 552 743 | 223 788 | 831 629 | ||||||||

| Payment for birth | ||||||||||||

| Private | 52.0 | 50.6 | −0.6 (−0.8 to −0.4) | 65.9 | 65.3 | −0.6 (−0.8 to −0.4) | −0.9 (−1.3 to −0.5) | <.001 | −0.3 (−0.6 to 0.01) | .05 | −4.2 (−4.6 to −3.7) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 35.1 | 36.7 | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 24.1 | 24.9 | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.1) | <.001 | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) | .15 | 3.8 (3.3 to 4.3) | <.001 |

| Self-pay | 5.2 | 4.9 | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | 4.5 | 4.3 | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.02) | .08 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.01) | .07 | 0.0 (−0.3 to 0.3) | 1.00 |

| Prenatal care | ||||||||||||

| Early prenatal cared | 75.4 | 76.7 | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 80.4 | 81.1 | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.8) | <.001 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0) | <.001 | −0.1 (−0.7 to 0.4) | .66 |

| Adequate prenatal caree | 77.6 | 78.8 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.4) | 80.9 | 82.1 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.4) | −0.04 (−0.3 to 0.3) | .80 | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.4) | .47 | −0.5 (−1.0 to 0.1) | .08 |

| Birth outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Cesarean delivery | 28.6 | 27.8 | −1.1 (−1.3 to −0.9) | 31.3 | 30.2 | −1.1 (−1.3 to −0.9) | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.6) | .17 | 0.3 (−0.1 to 0.6) | .12 | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.4) | <.001 |

| Preterm birth | 8.6 | 8.1 | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) | 8.4 | 8.1 | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) | −0.2 (−0.4 to −0.03) | .03 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.05) | .14 | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.5) | .46 |

| Low birth weightf | 6.4 | 6.2 | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.05) | 6.3 | 6.2 | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.05) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.03) | .10 | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.1) | .42 | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) | .40 |

| NICU admission | 6.1 | 6.5 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) | 6.2 | 6.7 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) | −0.2 (−0.3 to 0.02) | .08 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | .28 | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.4) | .35 |

Abbreviations: ACA, Affordable Care Act; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

All models analyze data from 2009-2013 excluding 2010 as the ACA policy implementation period and use robust standard errors.

Adjusted models are adjusted for month of delivery; a monthly linear time trend; maternal marital status; age; race; ethnicity; education; whether the birth was a woman’s first live birth; multiple delivery; paternal age; and monthly unemployment rates.

The adjusted difference between married and unmarried women is modeled as the interaction between the postpolicy period, exposure group, and marital status.

Early prenatal care is defined as having the first prenatal visit in the first trimester (0-3 mo).

Adequate prenatal care is defined by the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization (APNCU) index.

Low birth weight is defined as birth weight of an infant of less than 2500 g.

Prenatal Care

In unadjusted analyses, early prenatal care increased from 70% in 2009 to 71.6% in 2011-2013 (difference, 1.6%) in the exposure group and from 75.7% to 76.8% (difference, 1.1%) in the control group (unadjusted difference-in-differences, 0.6 percentage points [95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8]). Adequate prenatal care increased from 73.5% to 74.8% (difference, 1.3%) in the exposure group and from 77.5% to 78.8% (difference, 1.3%) in the control group (unadjusted difference-in-differences, 0.04 percentage points [95% CI, −0.2 to 0.3]).

In adjusted analyses, the policy was associated with a 1.0 percentage-point increase (95% CI, 0.7 to 1.2) in early prenatal care (P < .001; 1.4% relative increase from a baseline of 70%), and a 0.4 percentage-point increase (95% CI, 0.2 to 0.6) in adequate prenatal care (P < .001; 0.6% relative increase from a baseline of 74%). After adjusting for payment for birth, the association with early prenatal care was still significant but roughly 30% smaller in magnitude, and the association with adequate prenatal care was no longer significant (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

In stratified adjusted analyses, significant increases in early prenatal care were identified for both unmarried (0.8 percentage points [95% CI, 0.4 to 1.3], P < .001; 1.3% relative increase from a baseline of 64%) and married women (0.7 percentage points [95% CI, 0.4 to 1.0], P < .001; 0.9% relative increase from a baseline of 75%). Significant increases in adequate prenatal care were only present among unmarried women (0.6 percentage points [95% CI, 0.1 to 1.0], P = .01; 0.9% relative increase from a baseline of 68%); however, the differential change in adequate prenatal care between unmarried and married women was not statistically significant (−0.5 percentage points [95% CI, −1.0 to 0.1]).

Birth Outcomes

In unadjusted analyses, cesarean deliveries decreased from 30.1% in 2009 to 29.7% in 2011-2013 among the exposure group (difference, −0.4%) and from 32.1% to 31.5% among the control group (difference, −0.6%); unadjusted difference-in-differences, 0.2 percentage points (95% CI, −0.1 to 0.4). Preterm birth decreased from 9.4% to 9.1% in the exposure group (difference, −0.3%) and from 9.1% to 8.9% in the control group (difference, −0.2%), unadjusted difference-in-differences, −0.1 percentage points (95% CI, −0.3 to 0.04). Low birth weight increased from 7.5% to 7.6% in the exposure group (difference, 0.1%) and did not change from 7.2% in the control group (difference, −0.005%), unadjusted difference-in-differences, 0.1 percentage points (95% CI, −0.1 to 0.2). NICU admission increased from 6.7% to 7.3% in the exposure group (difference, 0.6%) and from 6.6% to 7.3% in the control group (difference, 0.7%), unadjusted difference-in-differences, −0.1 percentage points (95% CI, −0.2 to 0.1).

In adjusted analyses, the policy was associated with a statistically significant decrease in preterm birth (−0.2 percentage points [95% CI, −0.3 to −0.03], P = .02; 2.2% relative decrease from a baseline of 9.4%), but not with changes in cesarean delivery, low birth weight, or NICU admission. The association with preterm birth was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for payment for birth (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

In stratified analyses, the policy was associated with significant decreases in preterm birth (−0.3 percentage points [95% CI, −0.5 to 0.002], P = .05; 2.9% relative decrease from a baseline of 10.3% and cesarean delivery (−0.6 percentage points [95% CI, −1.0 to −0.2], P = .01; 1.9% relative decrease from a baseline of 32%) among unmarried women only. The differential change between unmarried and married women was significant for cesarean deliveries (0.9 percentage points [95% CI, 0.4 to 1.4]) but not for preterm birth (0.1 percentage points [95% CI, −0.2 to 0.5]).

Discussion

In this national study of prenatal care and birth outcomes among young adults, the ACA dependent coverage provision was associated with a significant increase in private insurance payment and a reduction in Medicaid payment for childbirth. The provision was also associated with modest but statistically significant increases in early and adequate prenatal care. For secondary birth outcomes, the dependent coverage provision was associated with modest decreases in preterm births, but no significant reduction in cesarean deliveries, low birth weight, or infant NICU admissions.

The study findings for changes in payment for birth are consistent with the study by Akosa Antwi et al, which found a 2.5 percentage-point increase in privately paid births, a 2.1 percentage-point decrease in Medicaid paid births, and a 0.3 percentage-point decrease in self-paid births. The small decrease in uninsured births associated with the policy contrasts with studies of the general young adult population, which estimated decreases of uninsurance from 3.0 to 4.7 percentage points, driven almost entirely by shifts from uninsurance to private insurance. This difference reflects the special role Medicaid plays in covering pregnant women. Medicaid paid for 45% of US births in 2010, and even if a woman is uninsured for most of her pregnancy, by the time of delivery, there is a high likelihood she will have obtained Medicaid, if she is eligible. Hospitals have a strong incentive to enroll eligible women even after delivery to obtain payment (Medicaid pays retroactive costs for eligible individuals for up to 3 months prior to enrollment). Thus, the estimates of payment for birth in this study likely understate the role the policy played in increasing preconception and postconception coverage and the number of months women were insured during pregnancy.

Unmarried women experienced a 20% relative increase in private coverage (3.8 percentage points) in contrast to no significant change among married women. This is consistent with the study by Akosa Antwi et al, which also found significant changes in payment for birth among unmarried women only. Without the option of spousal coverage, unmarried women were less likely to have private insurance before the ACA and more likely to benefit from the provision. The finding that changes in adequate prenatal care, preterm birth, and cesarean deliveries were only significant among unmarried women is consistent with the interpretation that the observed changes in prenatal care and birth outcomes are related to changes in payment for birth, and direct adjustment for payment attenuated the observed changes in prenatal care and birth outcomes.

The improvement in prenatal care observed in this study is consistent with previous research showing that women with preconception coverage are better able to access clinicians early in pregnancy. Other research has shown that having private insurance at delivery is associated with higher rates of continuous coverage before, during, and after pregnancy compared with pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage, which only covers women from conception to 60 days postpartum.

The estimated increases in prenatal care utilization (1.0 percentage points for early prenatal care and 0.4 percentage points for adequate prenatal care) are modest but not negligible when considered in the context of other interventions aimed to improve prenatal care use. Evidence from pregnancy-related Medicaid expansions in the 1980s found that despite large increases in coverage, gains in prenatal care use were inconsistent. For example, Epstein and Newhouse observed an increase of 3 percentage points in early prenatal care in South Carolina but no improvement in California. Similarly modest evidence exists for community-based interventions to improve prenatal care. For example, evidence on home-visiting programs for high-risk women have found results ranging from no significant difference to a 4.5 percentage-point increase in adequate prenatal care use, suggesting that this study’s estimates for the dependent coverage provision are in the range of changes detected after more intensive interventions.

Given the relatively small coverage and utilization changes associated with the policy, it is not surprising that changes in birth outcomes were small in magnitude. These modest results are similar to previous studies of coverage expansions to pregnant women, which have found small or no changes in premature birth, cesarean delivery, and low birth weight, despite improvements in prenatal care. Although prenatal care is not the only mechanism through which expansion of coverage might affect birth outcomes (eFigure in the Supplement), evidence on the effectiveness of routine prenatal care is mixed. Regardless, it is likely that insurance coverage is still important to improve access to such interventions.

The dependent coverage provision is one of many components of the ACA with the potential to affect reproductive-age and pregnant women. Future research should examine the effect of other aspects of the law on insurance coverage during pregnancy and resulting effects on access to care, maternal outcomes, and both short-term and long-term children’s health outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, difference-in-differences analysis relies on the assumption that the trend after implementation for the control group is a valid counterfactual for what would have been observed in the exposure group, if not for the policy. Based on an analysis of monthly prepolicy trends, this study used narrower age bands than previous studies. Small but significant divergent trends and placebo effects were detected for early prenatal care and NICU admission among unmarried women, suggesting that results for these outcomes should be interpreted with caution.

Second, although the use of narrow age bands improves the study’s internal validity, this approach only estimates the association between the provision and outcomes for births to women aged 24 to 25 years. The provision may have differentially affected women of younger ages, among whom rates of prenatal care are typically lower and risk of adverse birth outcomes higher.

Third, without state identifiers, the analysis could not be restricted to states based on the year they adopted the 2003 birth certificate format. A previous analysis of the dependent coverage provision and payment for childbirth compared the data used in this study with the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database and found similar results, suggesting this threat to validity is limited for payment-related outcomes. Though regression models controlled for observed covariates, unobserved changes in the composition of the exposure and control group over time could bias the results.

Conclusions

In this study of nearly 3 million births among women aged 24 to 25 years compared with those aged 27 to 28 years, the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage provision was associated with increased private insurance payment for birth, increased use of prenatal care, and modest reduction in preterm births, but was not associated with changes in cesarean delivery rates, low birth weight, or neonatal intensive care unit admission.

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Directed Acyclic Graph

eTable 1. Pre-Period Trend Differences Between the Exposure Group and Control Group for Different Exposure and Control Group Definitions

eTable 2. Pre-Period Trend Differences Between the Exposure Group and Control Group, Stratified by Marital Status

eTable 3. Placebo Tests, Stratified by Marital Status

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis With Clustered Standard Errors

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis Adjusting for Tobacco Use

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis Adjusting for Payment Source

eTable 7. Maternal and Paternal Characteristics Before and After the Dependent Coverage Provision, Stratified by Marital Status

References

- 1.Sommers BD, Buchmueller T, Decker SL, Carey C, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act has led to significant gains in health insurance and access to care for young adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):165-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers BD, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage for young adults. JAMA. 2012;307(9):913-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chua K-P, Sommers BD. Changes in health and medical spending among young adults under health reform. JAMA. 2014;311(23):2437-2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han X, Yabroff KR, Robbins AS, Zheng Z, Jemal A. Dependent coverage and use of preventive care under the Affordable Care Act (published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):782). N Engl J Med. 2014;371(24):2341-2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akosa Antwi Y, Moriya AS, Simon K, Sommers BD. Changes in emergency department use among young adults after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s dependent coverage provision. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(6):664-672.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez-Boussard T, Burns CS, Wang NE, Baker LC, Goldstein BA. The Affordable Care Act reduces emergency department use by young adults: evidence from three states. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1648-1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akosa Antwi Y, Ma J, Simon K, Carroll A. Dependent coverage under the ACA and Medicaid coverage for childbirth. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):194-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenberg D, Handler A, Rankin KM, Zimbeck M, Adams EK. Prenatal care initiation among very low-income women in the aftermath of welfare reform: does pre-pregnancy Medicaid coverage make a difference? Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(1):11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braveman P, Marchi K, Egerter S, Pearl M, Neuhaus J. Barriers to timely prenatal care among women with insurance: the importance of prepregnancy factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):874-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partridge S, Balayla J, Holcroft CA, Abenhaim HA. Inadequate prenatal care utilization and risks of infant mortality and poor birth outcome: a retrospective analysis of 28 729 765 US deliveries over 8 years. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(10):787-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein AB, Cohen RA, Brett KM, Bush MA. Marital status is associated with health insurance coverage for working-age women at all income levels, 2007. NCHS Data Brief. 2008;(11):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan AM, Burgess JF Jr, Dimick JB. Why we should not be indifferent to specification choices for difference-in-differences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1211-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slusky DJG. Significant placebo results in difference-in-differences analysis: the case of the ACA’s parental mandate [published online November 9, 2015]. East Econ J. 2015. doi: 10.1057/eej.2015.49 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace J, Sommers BD. Health insurance effects on preventive care and health: a methodologic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(5)(suppl 1):S27-S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):947-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wherry LR, Fabi R, Schickedanz A, Saloner B. State and federal coverage for pregnant immigrants: prenatal care increased, no change detected for infant health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):607-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommers BD, Gawande AA, Baicker K. Health insurance coverage and health—what the recent evidence tells us. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):586-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daw JR, Hatfield LA, Swartz K, Sommers BD. Women in the United States experience high rates of coverage ‘churn’ in months before and after childbirth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):598-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotelchuck M. An evaluation of the Kessner adequacy of prenatal care index and a proposed adequacy of prenatal care utilization index. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(9):1414-1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huesch MD. Association between type of health insurance and elective cesarean deliveries: New Jersey, 2004-2007. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):e1-e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aron DC, Gordon HS, DiGiuseppe DL, Harper DL, Rosenthal GE. Variations in risk-adjusted cesarean delivery rates according to race and health insurance. Med Care. 2000;38(1):35-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein AM, Newhouse JP. Impact of Medicaid expansion on early prenatal care and health outcomes. Health Care Financ Rev. 1998;19(4):85-99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Currie J, Gruber J. Public health insurance and medical treatment: the equalizing impact of the Medicaid expansions. J Public Econ. 2001;82(1):63-89. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(00)00140-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howell EM. The impact of the Medicaid expansions for pregnant women: a synthesis of the evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2001;58(1):3-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Showstack JA, Budetti PP, Minkler D. Factors associated with birth weight: an exploration of the roles of prenatal care and length of gestation. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(9):1003-1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray JL, Bernfield M. The differential effect of prenatal care on the incidence of low birth weight among blacks and whites in a prepaid health care plan. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(21):1385-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Currie J, Gruber J. Saving babies: the efficacy and cost of recent changes in the Medicaid eligibility of pregnant women. J Polit Econ. 1996;104(6):1263-1296. https://doi.org/ 10.1086/262059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Jongh BE, Locke R, Paul DA, Hoffman M. The differential effects of maternal age, race/ethnicity and insurance on neonatal intensive care unit admission rates. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor Labor force statistics from the current population survey. https://www.bls.gov/cps/. Accessed May 16, 2017.

- 30.Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, Musco T. Changes in self-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314(4):366-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wherry LR, Miller S. Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):795-803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markus AR, Andres E, West KD, Garro N, Pellegrini C. Medicaid covered births, 2008 through 2010, in the context of the implementation of health reform. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(5):e273-e280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Eligibility. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/eligibility/. Accessed June 19, 2017.

- 34.Issel LM, Forrestal SG, Slaughter J, Wiencrot A, Handler A. A review of prenatal home-visiting effectiveness for improving birth outcomes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40(2):157-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(4):306-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiscella K. Does prenatal care improve birth outcomes? a critical review. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(3):468-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krans EE, Davis MM. Preventing low birth weight: 25 years, prenatal risk, and the failure to reinvent prenatal care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):398-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez Turienzo C, Sandall J, Peacock JL. Models of antenatal care to reduce and prevent preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e009044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wise PH. Transforming preconceptional, prenatal, and interconceptional care into a comprehensive commitment to women’s health. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(6)(suppl):S13-S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Directed Acyclic Graph

eTable 1. Pre-Period Trend Differences Between the Exposure Group and Control Group for Different Exposure and Control Group Definitions

eTable 2. Pre-Period Trend Differences Between the Exposure Group and Control Group, Stratified by Marital Status

eTable 3. Placebo Tests, Stratified by Marital Status

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis With Clustered Standard Errors

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis Adjusting for Tobacco Use

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis Adjusting for Payment Source

eTable 7. Maternal and Paternal Characteristics Before and After the Dependent Coverage Provision, Stratified by Marital Status