Abstract

Importance

Undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease have variable access to hemodialysis in the United States despite evidence-based standards for frequency of dialysis care.

Objective

To determine whether mortality and health care use differs among undocumented immigrants who receive emergency-only hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis (3 times weekly at a health care center).

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study was conducted of undocumented immigrants with incident end-stage renal disease who initiated emergency-only hemodialysis (Denver Health, Denver, Colorado, and Harris Health, Houston, Texas) or standard (Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco, California) hemodialysis between January 1, 2007, and July 15, 2014.

Exposures

Access to emergency-only hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was mortality. Secondary outcomes were health care use (acute care days and ambulatory care visits) and rates of bacteremia. Outcomes were adjusted for propensity to undergo emergency hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis.

Results

A total of 211 undocumented patients (86 women and 125 men; mean [SD] age, 46.5 [14.6] years; 42 from the standard hemodialysis group and 169 from the emergency-only hemodialysis group) initiated hemodialysis during the study period. Patients receiving standard hemodialysis were more likely to initiate hemodialysis with an arteriovenous fistula or graft and had higher albumin and hemoglobin levels than patients receiving emergency-only hemodialysis. Adjusting for propensity score, the mean 3-year relative hazard of mortality among patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis was nearly 5-fold (hazard ratio, 4.96; 95% CI, 0.93-26.45; P = .06) greater compared with patients who received standard hemodialysis. Mean 5-year relative hazard of mortality for patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis was more than 14-fold (hazard ratio, 14.13; 95% CI, 1.24-161.00; P = .03) higher than for those who received standard hemodialysis after adjustment for propensity score. The number of acute care days for patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis was 9.81 times (95% CI, 6.27-15.35; P < .001) the expected number of days for patients who had standard hemodialysis after adjustment for propensity score. Ambulatory care visits for patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis were 0.31 (95% CI, 0.21-0.46; P < .001) times less than the expected number of days for patients who received standard hemodialysis.

Conclusions and Relevance

Undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease treated with emergency-only hemodialysis have higher mortality and spend more days in the hospital than those receiving standard hemodialysis. States and cities should consider offering standard hemodialysis to undocumented immigrants.

This cohort study examines whether mortality and health care use differs among undocumented immigrants who receive standard hemodialysis (3 times weekly at a health care center) vs emergency-only hemodialysis.

Key Points

Question

Do mortality and health care use differ between undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease treated with emergency-only hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis (3 times weekly)?

Findings

In this cohort study, mean 5-year mortality for patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis was more than 14-fold higher than for those who received standard hemodialysis. Patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis had more inpatient days but fewer outpatient clinic visits than those who received standard hemodialysis.

Meaning

Availability of standard hemodialysis for undocumented immigrants could both save lives and reduce inpatient resource use, suggesting the need for a careful examination and potential change of existing health care policies.

Introduction

In the United States, approximately 6500 undocumented immigrants have end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Undocumented immigrants with ESRD are primarily Hispanic and, compared with documented Hispanic patients with ESRD, tend to be younger, have a lower educational level, and are less likely to receive predialysis care. The accessibility to emergency-only hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis (3 times weekly at a health care center) varies between and within states for undocumented immigrants despite evidence-based clinical practice guidelines recommending standard hemodialysis. Kidney transplantation, which offers improved quality of life, survival, and long-term costs compared with hemodialysis, is rarely an option for undocumented immigrants owing to its high initial cost and local policies. This variation in availability of hemodialysis is in part owing to restrictions in insurance coverage based on citizenship. Nearly all US citizens and 5-year permanent residents are eligible for standard hemodialysis as a result of the 1972 ESRD Amendments to the Social Security Act (Public Law 92-603). Undocumented immigrants are excluded from the major federally funded insurance programs, such as Medicare or Medicaid, as well as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Public Law 111-148). Some states use state funding to finance chronic dialysis care for undocumented immigrants, although most provide emergency-only dialysis to these patients. The origins of emergency-only dialysis began with the 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) amendment, which allows the use of federal Medicaid funds for medical services provided to undocumented immigrants if “such care and services…[are] necessary for the treatment of an emergency medical condition.”(p62) Therefore, in many states, the interpretation results in many patients not receiving dialysis until severe complications of advanced kidney disease appear, including uremia, volume overload, hyperkalemia, hypertension, metabolic acidosis, and mental status changes.

To our knowledge, there are no studies comparing outcomes among undocumented immigrants with ESRD who receive variable treatment based on policies in different locations. Therefore, we conducted a study to examine mortality and health care use between undocumented immigrants undergoing emergency-only hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis.

Methods

Design, Participants, and Setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of undocumented immigrant patients with ESRD who initiated hemodialysis at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (ZSFG), Denver Health (DH), or Harris Health (HH) from January 1, 2007, to July 15, 2014, and followed up patients until death, loss to follow-up, or July 15, 2014. Patients were eligible if they had a recorded start date of hemodialysis (ie, patient’s first hemodialysis session), date of last contact (ie, patient transitioned to standard hemodialysis care, moved away, or died), at least 3 months of treatment, and no prior peritoneal dialysis. We required at least 3 months of treatment because a patient is diagnosed with ESRD only after 90 days of consecutive hemodialysis, and some patients may decide to not continue care at the site of initial presentation. The study was approved and patient consent was waived by institutional review boards at the University of Colorado, HH, Baylor College of Medicine, and the University of California San Francisco.

Sites vary by hemodialysis and vascular access practices for undocumented immigrant patients. At ZSFG, an arteriovenous fistula is placed and patients receive standard hemodialysis in an outpatient setting. At DH, an arteriovenous fistula is placed; however, patients are required to have an emergency presentation before being admitted to receive 2 consecutive hemodialysis sessions on 2 consecutive days. On average, patients present for emergency-only hemodialysis every 6 to 7 days. At HH, patients initiate hemodialysis with a tunneled dialysis catheter, and patients are provided 1 hemodialysis session following presentation to the emergency department. On average, patients present for emergency-only hemodialysis 2 to 3 times per week. At both HH and DH, to receive emergency-only hemodialysis, the patient must be critically ill, defined as presence of any of the following: elevated potassium; low bicarbonate; low oxygen saturation; uremic symptoms including confusion, substantial nausea and vomiting, mental status changes, or other neurologic signs and symptoms; and shortness of breath.

Data Collection

We collected data from medical and administrative records. Demographic data included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Baseline clinical data, documented within 1 month of initiation of dialysis, included care by a nephrologist prior to initiation of dialysis, history of type 1 or 2 diabetes, comorbid disease, smoking status, assigned cause of ESRD, type of vascular access at initiation of hemodialysis (catheter, arteriovenous fistula, or arteriovenous graft), and albumin, hemoglobin, and phosphorus levels. A Charlson Comorbidity Index score was calculated through medical record review using comorbidities documented at the time of initiation of dialysis.

We observed patients from the initiation of dialysis to their last known contact date during the study period. Death, the main outcome, was ascertained by review of the medical record. Data on secondary outcomes of health care use (inpatient days and ambulatory care visits) and episodes of bacteremia (blood culture proven) were also collected during the study follow-up period at the site where patients received hemodialysis. All outpatient encounters, including those unrelated to dialysis (primary and subspecialty care), qualified as ambulatory care visits.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc). We first examined differences between the 2 emergency-only hemodialysis sites (DH and HH) to determine whether it would be appropriate to combine the sites into a single study group. We compared patient characteristics using the t test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, and χ2 test. An unadjusted Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to detect differences in mortality. Results of these tests supported combining the 2 sites into a single study group. We then compared patient characteristics of the emergency-only hemodialysis group with those of the standard hemodialysis group using the t test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, and χ2 test.

We used the balancing property of propensity scores to compare similar patient profiles in adjusted analyses. Scores were calculated using coefficients from a logistic regression model predicting exposure to emergency-only hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis, including variables associated with both the exposure and the outcome and variables associated with the outcome only in bivariate analysis. Colinear variables statistically (P < .05) or clinically associated with both the exposure and outcome took precedence over those only associated with the outcome. Using multiple imputation procedures, we imputed missing values for prior nephrology access at initiation and albumin at initiation. Other variables included in the propensity score calculation were Charlson Comorbidity Index score, smoking status, age at initiation, and history of diabetes. The selected propensity score was strongly associated with group status among all patients (C statistic = 0.91-0.92).

We constructed cumulative mortality curves using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis methods. Surviving patients were censored at the last date of follow-up. A violation of the proportional hazards assumption was detected using Schoenfeld residual plots and tests for interactions between time and dialysis care (eFigure in the Supplement). To address the violation, we introduced a time-varying covariate. The new covariate describes the interaction of ln (time) and dialysis care and permits the use of Cox proportional hazards regression modeling while allowing for nonproportional hazards. To describe the outcome of dialysis care during the course of 1, 3, and 5 years of follow-up, we estimated the hazard ratios at the midpoint of each follow-up period. Using this approach, we modeled unadjusted and propensity score–adjusted data for all patients and for Hispanic patients only. The reference group was standard hemodialysis. Hazard ratios with 95% CIs were calculated.

A multivariate nonproportional hazards modeling approach was compared with the propensity score–adjusted mortality analyses. A second sensitivity analysis was performed by expanding the study’s analytic sample to include patients with less than 3 months of follow-up and repeating the mortality analyses.

To examine the association of dialysis exposure group with health care use and rates of bacteremia, we constructed unadjusted and propensity score–adjusted, zero-inflated Poisson and zero-inflated negative binomial regression models. We assessed goodness of fit using a scaled Pearson χ2 test. If overdispersion was detected, we would instead model data using zero-inflated negative binomial regression. Rate ratios with 95% CIs were calculated.

Using standardized mortality ratios, we compared 1-, 3-, and 5-year mortality rates among patients who received emergency-only or standard hemodialysis with mortality rates among the 2007-2011 ESRD population provided by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Expected mortalities for the study hemodialysis groups were calculated using 2007-2011 age-stratified and sex-stratified crude mortality rates for the USRDS population with ESRD. We repeated these analyses after limiting the comparison to Hispanic patients. Results are presented with 95% CIs. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Study Sample and Patient Characteristics

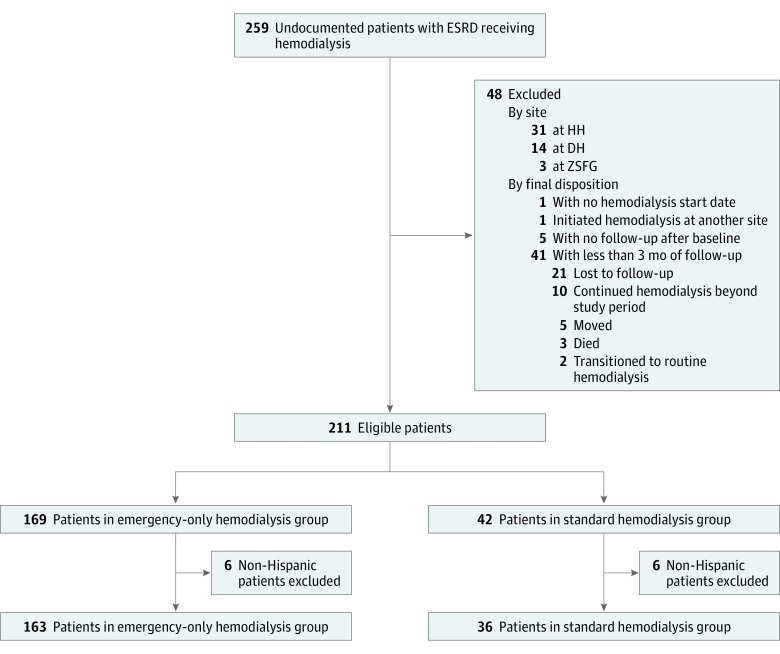

We identified 259 undocumented immigrant patients with ESRD who were receiving hemodialysis at the 3 study sites. Forty-eight patients were excluded for the following reasons: no hemodialysis start date (n = 1), initiated hemodialysis at another site (n = 1), no follow-up beyond baseline (n = 5), and did not have 3 months of follow-up (n = 41) (Figure 1). The median follow-up period for HH was 1.02 years (interquartile range, 0.68-1.65 years), for DH was 1.51 years (interquartile range, 0.73-2.97 years), and for ZSFG was 2.53 years (interquartile range, 1.26-4.31 years). Of the 211 patients studied (mean [SD] age, 46.5 [14.6] years), 169 were in the emergency-only hemodialysis group (47 at DH and 122 at HH) and 42 were in the standard hemodialysis group (ZSFG) (Table 1). There were 199 Hispanic patients: 163 in the emergency-only hemodialysis group and 36 in the standard hemodialysis group.

Figure 1. Patient Flow Diagram.

DH indicates Denver Health; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HH, Harris Health; and ZSFG, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Provided Emergency-Only Hemodialysis or Standard Hemodialysis.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency-Only Hemodialysis (n = 169) |

Standard Hemodialysis (n = 42) |

||

| Treatment location | |||

| Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco, CA | NA | 42 (100) | NA |

| Denver Health, Denver, CO | 47 (27.8) | NA | |

| Harris Health, Houston, TX | 122 (72.2) | NA | |

| Age at hemodialysis initiation, mean (SD), ya | 45.9 (14.5) | 48.8 (15.3) | .26 |

| Male sex | 94 (55.6) | 31 (73.8) | .03 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 4 (2.4) | 4 (9.5) | .02 |

| Black | 1 (0.6) | 0 | |

| Hispanic | 163 (96.4) | 36 (85.7) | |

| White | 1 (0.6) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Other | 0 | 1 (2.4) | |

| Prior nephrology care | |||

| Yes | 90 (53.3) | 27 (64.3) | <.001 |

| No | 77 (45.6) | 0 | |

| Missing | 2 (1.2) | 15 (35.7) | |

| History of type 1 or 2 diabetesa | 94 (55.6) | 23 (54.8) | .92 |

| History of CVD | 65 (38.5) | 22 (52.4) | .10 |

| Charlson comorbidity index score,a median (interquartile range [Q1-Q3])b | 4.0 (2.0-6.0) | 3.5 (2.0-5.0) | .06 |

| Assigned cause of ESRDa | |||

| Diabetes | 85 (50.3) | 15 (35.7) | .11 |

| Hypertension | 21 (12.4) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Other | 28 (16.6) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Unknown | 35 (20.7) | 8 (19.0) | |

| Vascular access at initiation | |||

| Catheter | 163 (96.4) | 32 (76.2) | <.001 |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 5 (3.0) | 9 (21.4) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.6) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Serum albumin, mean (SD), mg/dLa,c | 2.9 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.7) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD), mg/dLc | 8.0 (1.6) | 9.2 (2.2) | .002 |

| Phosphorus, mean (SD), mg/dLd | 7.9 (2.2) | 7.3 (2.3) | .12 |

| Current smokera | 13 (7.7) | 4 (9.5) | .75 |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; NA, not applicable; Q1, first quarter; Q3, third quarter.

SI conversion factors: To convert albumin to grams per liter, multiply by 10.0; to convert hemoglobin to grams per liter, multiply by 10.0; and to convert phosphorus to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.323.

Characteristics associated with 1-, 3- or 5-year mortality.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index includes liver disease, CVD, cerebrovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, AIDS, and cancer.

Data missing for 2 patients.

Data missing for 8 patients.

Compared with patients in the emergency-only hemodialysis group, those in the standard hemodialysis group had more prior nephrology care, more arteriovenous fistulas, higher serum albumin levels, and higher hemoglobin levels at initiation of hemodialysis. Sex and race/ethnicity also differed between dialysis care groups. During a 30-day period, the mean number of hemodialysis sessions received was 10.34 for patients who received standard hemodialysis care and 6.26 for patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis care.

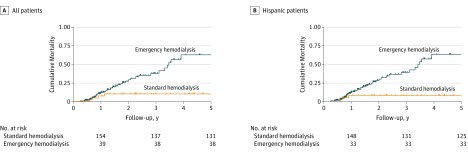

Mortality

Adjusting for propensity score, the mean 3-year relative hazard of mortality among patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis was nearly 5-fold (hazard ratio, 4.96; 95% CI, 0.93-26.45; P = .06) greater compared with patients who received standard hemodialysis (Table 2 and Figure 2). The adjusted mean 5-year relative hazard of mortality among patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis care was more than 14-fold higher than among those who received standard hemodialysis (hazard ratio, 14.13; 95% CI, 1.24-161.00; P = .03). Similar findings in mean 1-, 3-, and 5-year mortality were observed in Hispanic patients only. The multivariate modeling showed the same results (eTable 1 in the Supplement). When we expanded the sample to include patients with less than 3 months of follow-up, we observed slightly larger hazard ratios in comparison with the study’s original samples (eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Deaths and Approximated Hazard Ratios for Patients Treated With Emergency Hemodialysis vs Standard Hemodialysis for 1, 3, and 5 Years of Follow-up.

| Follow-up Period, y | No. of Deaths | No. of Patient-years | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

| All Patients | ||||

| 1 Year | ||||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 15 | 139.60 | 0.94 (0.22-4.07) | 0.52 (0.10-2.67) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 3 | 39.24 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 3 Years | ||||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 32 | 230.07 | 8.70 (1.89-40.09) | 4.96 (0.93-26.45) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 4 | 91.72 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 5 Years | ||||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 38 | 246.82 | 24.49 (2.37-252.80) | 14.13 (1.24-161.00) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 4 | 115.57 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Hispanic Patients | ||||

| 1 Year | ||||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 15 | 133.88 | 1.01 (0.21-4.85) | 0.51 (0.09-2.89) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 3 | 34.54 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 3 Years | ||||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 32 | 220.44 | 14.12 (1.80-110.90) | 7.34 (0.83-64.76) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 3 | 80.89 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 5 Years | ||||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 38 | 237.18 | 48.19 (2.09-1110.30) | 25.40 (1.03-629.20) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 3 | 102.38 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Adjusted for propensity to undergo emergency hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis score. Variables included in the propensity score include age, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, history of type 1 or 2 diabetes, prior nephrology care, serum albumin level, and smoking status.

Figure 2. Cumulative Mortality for Patients Treated With Emergency Hemodialysis vs Standard Hemodialysis.

Hospital Days, Ambulatory Care Visits, and Bacteremia Episodes

During 5 years of follow-up, adjusting for propensity score, the number of acute care days for patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis was almost 10-fold greater (rate ratio, 9.81; 95% CI, 6.27-15.35; P < .001) and the number of ambulatory care visits was 3-fold less (rate ratio, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.21-0.46; P < .001) among patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences in the expected number of bacteremia episodes between groups during 5 years of follow-up (adjusted rate ratio, 2.31; 95% CI, 0.80-6.70; P = .12). Similar results were obtained for Hispanic patients only, although there was a more pronounced difference in the number of acute care days for patients who received emergency-only hemodialysis compared with those who received standard hemodialysis (adjusted rate ratio, 15.28; 95% CI, 10.14-23.03; P < .001).

Table 3. Health Care Use and Bacteremia Episodes in Emergency Hemodialysis vs Standard Hemodialysis Groups for 5 Years of Follow-up.

| Characteristic, Care Group | No. of Events per 100 Patient-days | Rate Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||

| All Patients | |||

| Acute care days | |||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 24.60 | 11.04 (7.39-16.49) | 9.81 (6.27-15.35) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 1.10 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ambulatory care visits | |||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 1.84 | 0.30 (0.22-0.41) | 0.31 (0.21-0.46) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 3.24 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Bacteremia episodes | |||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 0.09 | 3.16 (1.29-7.74) | 2.31 (0.80-6.70) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 0.01 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Hispanic Patients | |||

| Acute care days | |||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 24.51 | 15.38 (11.19-21.14) | 15.28 (10.14-23.03) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 0.82 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Ambulatory care visits | |||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 1.85 | 0.32 (0.22-0.44) | 0.36 (0.23-0.56) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 3.01 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Bacteremia episodes | |||

| Emergency hemodialysis | 0.08 | 2.63 (1.08-6.42) | 1.64 (0.58-4.63) |

| Standard hemodialysis | 0.02 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Adjusted for propensity to undergo emergency hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis score. Variables included in the propensity score include age, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, history of type 1 or 2 diabetes, prior nephrology care, serum albumin level, and smoking status.

Comparison With Entire US Dialysis Population

Compared with the USRDS population, the 5-year age-adjusted standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) were greater (2.26; 95% CI, 1.60-3.10) for undocumented patients who had emergency-only hemodialysis and lower (0.84; 95% CI, 0.23-2.16) for undocumented patients who had standard hemodialysis. Compared with the Hispanic USRDS population, the 5-year age-adjusted SMR was greater (2.83; 95% CI, 2.00-3.88) for Hispanic undocumented patients who had emergency-only hemodialysis and lower (0.96; 95% CI, 0.20-2.80) for Hispanic undocumented patients who had standard hemodialysis.

Discussion

The results of this study show that, 5 years after initiating hemodialysis, undocumented immigrants with ESRD and access to emergency-only hemodialysis had 14-fold greater relative hazard of mortality, spent more time in the inpatient setting, and had fewer ambulatory clinic visits compared with undocumented immigrants with access to standard hemodialysis. The greater mortality among patients with access to emergency-only hemodialysis is consistent with data demonstrating poorer mortality outcomes among patients receiving standard hemodialysis who miss treatment sessions. These patients also experience a greater risk of hospitalization, more emergency department visits, and stays in the intensive care unit. Also consistent with our data are results of a study comparing a 2-day interdialytic period with a 1-day interdialytic period among patients in the United States undergoing standard hemodialysis, which demonstrated a higher rate of death following the longer interdialytic period.

One might ask if quality of care or practice differences could account for the mortality differences observed in our study. To address this question, we referred to dialysis facility–level ESRD quality measures published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). We used these data to compare SMRs between facilities providing standard hemodialysis to ESRD patients because the health care professionals providing care for the undocumented immigrant patients with ESRD are the same as those who provide care for the documented immigrant patients with ESRD receiving standard dialysis. These data indicate that ZSFG, where undocumented patients with ESRD receive standard hemodialysis, has an SMR of 0.89 compared with an SMR of 0.31 at the standard hemodialysis facility at DH and an SMR of 0.57 at the standard hemodialysis facility at HH, suggesting that better outcomes for patients receiving standard hemodialysis in our study cannot be attributed to quality of care differences across study sites.

Our study also demonstrates that patients with access to emergency-only hemodialysis spend 10-fold greater time in the inpatient setting and less time in the outpatient setting. Consistent with our findings, a 2015 study of patients who use an unusually high volume of health care services found that, although undocumented immigrants receiving emergency-only hemodialysis make up only 2% of such “superusers” in Colorado, they experience a higher mean number of annual hospital admissions and their cost of care greatly exceeds that of several other comparable superuser patient groups. A 2007 study by Sheikh-Hamad et al examined cost differences between 13 undocumented immigrants newly diagnosed as having ESRD who were receiving emergency-only care and 22 undocumented immigrants with existing ESRD and found that emergency-only hemodialysis care is nearly 4 times more costly owing to more emergency department visits and hospital admissions. Thus, limiting standard hemodialysis for undocumented immigrants is likely more costly over time owing to higher inpatient use.

Undocumented immigrants with ESRD receiving emergency-only care face physical and psychosocial distress related to their lack of access to scheduled hemodialysis. In a 2017 study focusing on understanding the illness experience of undocumented immigrants with ESRD, patients described weekly severe and potentially life-threatening illness episodes of uremic and respiratory symptom accumulation preceding their presentation to the emergency department. The inferior physical health among patients receiving emergency-only hemodialysis was also described in a study comparing the quality of life of undocumented immigrants who receive emergency-only hemodialysis vs standard hemodialysis. More than 90% of the patients receiving emergency-only hemodialysis were employed prior to initiating hemodialysis, yet only 14% were able to continue working owing to illness and irregular dialysis schedules. In addition to these challenges, patients and their families face considerable psychosocial distress around the possibility of death.

Standard (3 times weekly) hemodialysis is not prohibited by federal statutory and regulatory requirements, allowing for state-by-state coverage decisions. Beyond what is stated in EMTALA, the CMS defers to states to identify which conditions qualify as emergency medical conditions: “The broad definition [of emergency medical condition] allow states to interpret and further define the services available to aliens covered by section 1903 (v)(2) which are any services necessary to treat an emergency medical condition in a consistent and proper manner supported by professional medical judgment” (55 Federal Register 36 813, 36 816 [1990]). Confirming the state’s role in defining an emergency, the Office of Inspector General’s description of the legal framework governing emergency Medicaid was stated in 1997 and restated in 2010: “CMS allows each state to identify which conditions qualify as emergencies.”(p2) Municipalities and states providing standard hemodialysis to undocumented immigrants have unique sources of payment that may include federal matching funds or a modified state Medicaid emergency program. In Arizona, for example, where standard hemodialysis is provided to undocumented immigrants, administrative code states that “emergency services include outpatient hemodialysis…where a treating physician has certified that…the absence of receiving dialysis at least three times per week would reasonably be expected to result in: 1.) Placing the member’s health in serious jeopardy, or 2.) serious impairment of bodily function, or 3.) serious dysfunction of a bodily organ or part” (Arizona Administrative Code R9-22-217).(p25) Other states providing standard hemodialysis to undocumented immigrants include New York, California, Washington, and North Carolina.

Limitations and Strengths

Our study has limitations. We included undocumented immigrant patients with incident ESRD receiving hemodialysis from just 3 cities in the United States, limiting our sample size. Also, patients were not randomly allocated to care. Although one could compare outcomes for undocumented vs documented immigrants within a site, such a comparison would not take into account possible unmeasured differences between undocumented and documented immigrants that affect outcomes. It is possible that the lower mortality observed among undocumented immigrants with access to standard hemodialysis can be attributed to greater predialysis care (eg, primary care and specialty care). We were unable to ascertain cause of death or if a patient died at home, and we were unable to check deaths using the National Death Index owing to lack of Social Security numbers. In addition, it is possible that death is underestimated among undocumented immigrants receiving emergency-only hemodialysis, where contact with the health care system is sporadic, vs patients who receive standard hemodialysis, who are closely monitored by health care professionals. Because we examined health care use only at the sites where patients received hemodialysis care, it is possible we did not capture all health care use.

The strengths of our study are the longitudinal study design, with 5 years of follow-up from initiation of hemodialysis and the use of a propensity score with strong predictive accuracy to adjust for differences in characteristics of patients between standard hemodialysis and emergency-only hemodialysis.

Conclusions

An emergency-only hemodialysis treatment strategy to treat undocumented immigrants with ESRD is strongly associated with increased mortality and more acute hospital days compared with a treatment strategy of standard hemodialysis. The life-and-death nature of emergency-only hemodialysis demands that we establish policies guiding care for undocumented immigrants with ESRD and balancing the many conflicting issues. States across the country providing emergency-only hemodialysis to undocumented immigrants should reconsider the substantial human and economic effect of providing less-than-standard hemodialysis care.

eFigure. Schoenfeld Residuals vs Follow-up Years, by Dialysis Care Group

eTable 1. Deaths and Approximate Hazard Ratios for Patients Treated With Emergency vs Standard Care Over 1, 3, and 5 Years of Follow-up Using Multivariate Adjusted

eTable 2. A Comparison of Mortality Outcomes Between the Final Study Sample and the Expanded Sample Over 1, 3, and 5 Years of Follow-up

eTable 3. A Comparison of Mortality Outcomes Between the Final Hispanic Study Sample and the Expanded Hispanic Sample Over 1, 3, and 5 Years of Follow-up

References

- 1.Rodriguez RA. Dialysis for undocumented immigrants in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(1):60-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coritsidis GN, Khamash H, Ahmed SI, et al. The initiation of dialysis in undocumented aliens: the impact on a public hospital system. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(3):424-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurley L, Kempe A, Crane LA, et al. Care of undocumented individuals with ESRD: a national survey of US nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):940-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Kidney Foundation KDOQI clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):884-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grubbs V. Undocumented immigrants and kidney transplant: costs and controversy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(2):332-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linden EA, Cano J, Coritsidis GN. Kidney transplantation in undocumented immigrants with ESRD: a policy whose time has come? Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):354-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edward J. Undocumented immigrants and access to health care: making a case for policy reform. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2014;15(1-2):5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straube BM. Reform of the US healthcare system: care of undocumented individuals with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):921-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pub L No. 92-603 (1972), 1463. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg1329.pdf. Published October 30, 1972. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 10.Fernández A, Rodriguez RA. Undocumented immigrants and access to health care. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):536-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berlinger N, Gusmano MK. Health care access for undocumented immigrants under the Trump administration. http://undocumentedpatients.org/issuebrief/health-care-access-for-undocumented-immigrants-under-the-trump-administration/. Published December 19, 2016. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 12.Campbell GA, Sanoff S, Rosner MH. Care of the undocumented immigrant in the United States with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(1):181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.42 United States Code. 1395dd. Examination and treatment for emergency medical conditions and women in labor. US Government Printing Office; 2010. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2010-title42/html/USCODE-2010-title42-chap7-subchapXVIII-partE-sec1395dd.htm. Accessed October 26, 2017.

- 14.Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(12):1149-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Stated Renal Data System 2016 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Rayner HC, et al. Nonadherence in hemodialysis: associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):254-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leggat JE Jr, Orzol SM, Hulbert-Shearon TE, et al. Noncompliance in hemodialysis: predictors and survival analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(1):139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan KE, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW. Adherence barriers to chronic dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(11):2642-2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foley RN, Gilbertson DT, Murray T, Collins AJ. Long interdialytic interval and mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1099-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhee CM, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Implications of the long interdialytic gap: a problem of excess accumulation vs. excess removal? Kidney Int. 2015;88(3):442-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DialysisData. Dialysis facility report data. https://www.dialysisdata.org/content/dialysis-facility-report-data. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 22.Johnson TL, Rinehart DJ, Durfee J, et al. For many patients who use large amounts of health care services, the need is intense yet temporary. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1312-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheikh-Hamad D, Paiuk E, Wright AJ, Kleinmann C, Khosla U, Shandera WX. Care for immigrants with end-stage renal disease in Houston: a comparison of two practices. Tex Med. 2007;103(4):54-58, 53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cervantes L, Fischer S, Berlinger N, et al. The illness experience of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):529-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghavan R, Sheikh-Hamad D. Descriptive analysis of undocumented residents with ESRD in a public hospital system. Dial Transplant. 2011;40(2):78-81. doi: 10.1002/dat.20535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Federal Register. Vol 55. https://cdn.loc.gov/service/ll/fedreg/fr055/fr055174/fr055174.pdf. Published September 7, 1990. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 27.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Review of New Jersey's Medicaid emergency payment program for nonqualified aliens. Report A-02-07-01038. https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region2/20701038.pdf. Published April 22, 2010. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 28.Arizona Department of State, Office of the Secretary of State, Administrative Rules Division. Arizona Administrative Code. Title 9: health services: chapter 22: Arizona health care cost containment system—administration. http://apps.azsos.gov/public_services/Title_09/9-22.pdf. Updated June 30, 2017. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 29.Schrag WF. Insurance coverage for unauthorized aliens confusing and complex. Nephrology News & Issues July 9, 2015. https://www.nephrologynews.com/insurance-coverage-for-unauthorized-aliens-confusing-and-complex/. Accessed December 14, 2016. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Schoenfeld Residuals vs Follow-up Years, by Dialysis Care Group

eTable 1. Deaths and Approximate Hazard Ratios for Patients Treated With Emergency vs Standard Care Over 1, 3, and 5 Years of Follow-up Using Multivariate Adjusted

eTable 2. A Comparison of Mortality Outcomes Between the Final Study Sample and the Expanded Sample Over 1, 3, and 5 Years of Follow-up

eTable 3. A Comparison of Mortality Outcomes Between the Final Hispanic Study Sample and the Expanded Hispanic Sample Over 1, 3, and 5 Years of Follow-up