This comparative burden-of-disease study investigates the association of sex with the global burden of cataract by year, age, and socioeconomic status in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.

Key Points

Question

What is the association of sex with the global burden of cataract by year, age, and socioeconomic status?

Findings

In this international, comparative burden-of-disease study, differences in the global burden of cataract by sex persisted from 1990 through 2015, with women having higher rates of cataract than men. Older age and lower socioeconomic status were associated with greater differences in cataract rates by sex.

Meaning

These findings suggest that health policy should be sensitive to sex when addressing global vision loss caused by cataract.

Abstract

Importance

Eye disease burden could help guide health policy making. Differences in cataract burden by sex is a major concern of reducing avoidable blindness caused by cataract.

Objective

To investigate the association of sex with the global burden of cataract by year, age, and socioeconomic status using disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This international, comparative burden-of-disease study extracted the global, regional, and national sex-specific DALY numbers, crude DALY rates, and age-standardized DALY rates caused by cataract by year and age from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The DALY data were collected from January 1, 1990, through December 31, 2015, for ever 5 years. The human development index (HDI) in 2015 was extracted as an indicator of national socioeconomic status from the Human Development Report.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Comparisons of sex-specific DALY estimates due to cataract by year, age, and socioeconomic status at the global level. Paired Wilcoxon signed rank test, Pearson correlation, and linear regression analyses were performed to evaluate the socioeconomic-associated sex differences in cataract burden.

Results

Differences in rates of cataract by sex were similar between 1990 and 2015, with age-standardized DALY rates of 54.5 among men vs 65.0 among women in 1990 and 52.3 among men vs 67.0 among women in 2015. Women had higher rates than men of the same age, and sexual differences increased with age. Paired Wilcoxon signed rank test revealed that age-standardized DALY rates among women were higher than those among men for each HDI-based country group (z range, −4.236 to −6.093; P < .001). The difference (female minus male) in age-standardized DALY rates (r = −0.610 [P < .001]; standardized β = −0.610 [P < .001]) and the female to male age-standardized DALY rate ratios (r = −0.180 [P = .02]; standardized β = −0.180 [P = .02]) were inversely correlated with HDI.

Conclusions and Relevance

Although global cataract health care is progressing, sexual differences in cataract burden showed little improvement in the past few decades. Worldwide, women have a higher cataract burden than men. Older age and lower socioeconomic status are associated with greater differences in rates of cataract by sex. Our findings may enhance public awareness of sexual differences in global cataract burden and emphasize the importance of making sex-sensitive health policy to manage global vision loss caused by cataract.

Introduction

Although cataract is easily treatable, it remains a leading cause of visual impairment and blindness worldwide. According to the Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) Study 2010, 10.9 million people (33.4% of all persons with total blindness) were blind owing to cataract, and 35.1 million people (18.4% of all persons with total moderate to severe visual impairment) were visually impaired owing to cataract. Worldwide, women had a higher percentage of blindness and moderate to severe visual impairment caused by cataract compared with men. Globally, percentages of blindness due to cataract among women and men were 35.5% and 30.1%, respectively; for moderate to severe visual impairment, the estimates were 20.2% and 15.9%, respectively. A systematic review demonstrated that differences by sex regarding surgical services for cataract persisted in low- and middle-income countries, with men being 1.7 times more likely to undergo cataract surgery than women. Even in some developed countries, women had a poorer preoperative visual acuity and waited longer for cataract surgery than men. Globally, if women had the same access to cataract surgery as men, the blindness due to cataract could decrease by approximately 11%, which would be progress in global health care for eyes.

The burden of cataract has been estimated by quantifying health loss using disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). Based on DALY data from the GBD Study 2004, Ono et al first attempted to explore global inequality in eye diseases. They found that among all noncommunicable eye diseases, cataract had the most uneven distribution at the global level. The DALY estimates also allow direct comparison by sex of visual disability caused by cataract in broad epidemiologic patterns. Sexual difference in cataract burden is a major concern in reducing avoidable blindness that is worth more attention. Thus, the purpose of this study was to explore differences in global burden of cataract by sex over time across age groups and countries with different socioeconomic status using DALY data from the most recent GBD Study 2015.

Methods

Sex-Specific Estimates of Cataract Burden

Codes H25 to H25.2, H25.8 to H25.9, H26 to H26.4, H26.8 to H26.9, and Q12.0 from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, were mapped to cataract in the GBD Study 2015. Methods to calculate DALY estimates have been detailed in the GBD Study 2015 report. We extracted the following GBD Study 2015 data concerning cataract burden from the Global Health Data Exchange: (1) global sex-specific DALY numbers, crude rates (per 100 000 population), and age-standardized rates (per 100 000 population) in 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015; (2) World Health Organization regional sex-specific age-standardized DALY rates in 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015; (3) global sex- and age-specific DALY numbers and crude rates in 2015; and (4) national sex-specific age-standardized DALY rates in 2015. Because the GBD study data can be downloaded from an open access database, ethics approval and informed consent were not required for this study.

National Socioeconomic Status

The human development index (HDI), as an indicator of national socioeconomic status, is a composite measure of health, educational attainment, and income. We extracted the national HDI in 2015 from the Human Development Report 2016. The HDI ranges from 0 to 1.000, with higher values indicating higher levels of socioeconomic development. Countries were categorized into the following 4 groups based on HDI values in 2015: very high HDI (≥0.800), high HDI (<0.800 to ≥0.701), medium HDI (<0.701 to ≥0.550), and low HDI (<0.550).

Statistical Analysis

Global difference by sex in age-standardized DALY rates was tested using the paired Wilcoxon signed rank test, with further assessment of difference by sex for each HDI-based country group. Pearson correlation analyses and linear regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association of sex difference (female minus male) in age-standardized DALY rates and female to male age-standardized DALY rate ratio with HDI. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS software (version 23; IBM).

Results

Global Burden of Cataract by Sex

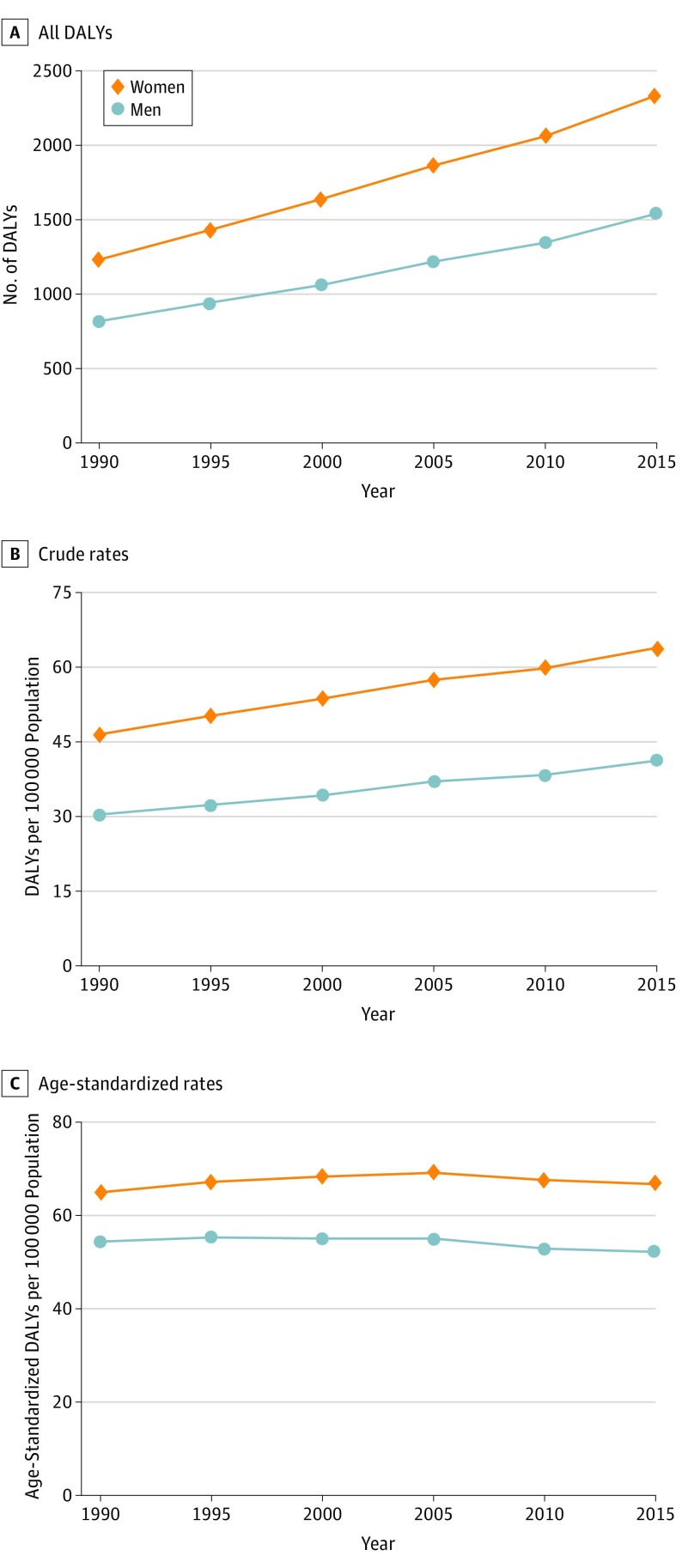

As seen in Figure 1, differences in the global burden of cataract by sex have persisted since 1990 and shown little improvement through 2015. The total DALY numbers in men vs women were 815 171 vs 1 233 008 in 1990 and 1 538 207 vs 2 341 534 in 2015 (Figure 1A). After controlling for the growth of population during the same period, greater difference by sex was found in 2015 (41.4 DALYs per 100 000 men vs 64.1 DALYs per 100 000 women) than in 1990 (30.6 DALYs per 100 000 men vs 46.8 DALYs per 100 000 women) (Figure 1B). After controlling for population size and age structure, age-standardized DALY rates decreased consistently from 54.5 in 1995 to 52.3 in 2015 among men and from 69.4 in 2005 to 67.0 in 2015 among women, implying global health progress in cataract in both sexes (Figure 1C). However, little improvement in difference by sex was observed between 1990 and 2015, with age-standardized DALY rates of 54.5 among men vs 65.0 among women in 1990 and 52.3 among men vs 67.0 among women in 2015.

Figure 1. Global Sex-Specific Burden of Cataract From 1990 to 2015.

Numbers of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) are given in thousands.

Regional trend plots indicated that in most World Health Organization regions, differences by sex in terms of age-standardized DALY rates persisted since 1990 with little improvement through 2015 except in the region of the Americas (eFigure in the Supplement). In the region of the Americas, the age-standardized DALY rates were almost the same in men and women in 1990 (37.6 and 37.7, respectively), whereas differences in rates by sex increased slowly through 2015 (38.0 in men vs 40.7 in women). However, among all the regions, the smallest gap in rates by sex was observed in the region of the Americas, with the largest gap observed in the Southeast Asia region (119.4 in men and 151.9 in women in 1990; 106.3 in men and 140.4 in women in 2015).

Global Sex-Specific Cataract Burden by Age

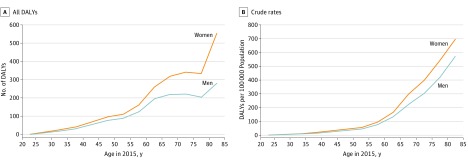

Global sex-specific DALY estimates for persons older than 20 years in 2015 were available from the GBD Study 2015. Overall, sex-specific DALY numbers (Figure 2A) and crude rates (Figure 2B) increased with age, as well as difference by sex in both estimates. Differences in rates by sex were almost negligible in the age range of 20 to 25 years and maximized at 80 years or older. Women 80 years or older had 554 216 DALYs due to cataract, almost twice that among men of the same age (280 788 DALYs). After controlling for population size, the greatest difference was also observed at 80 years or older, with 698.5 DALYs per 10 000 women vs 571.9 DALYs per 10 000 men.

Figure 2. Global Sex-Specific Cataract Burden by Age in 2015.

Numbers of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) are given in thousands.

Sex-Specific Cataract Burden by National Socioeconomic Status

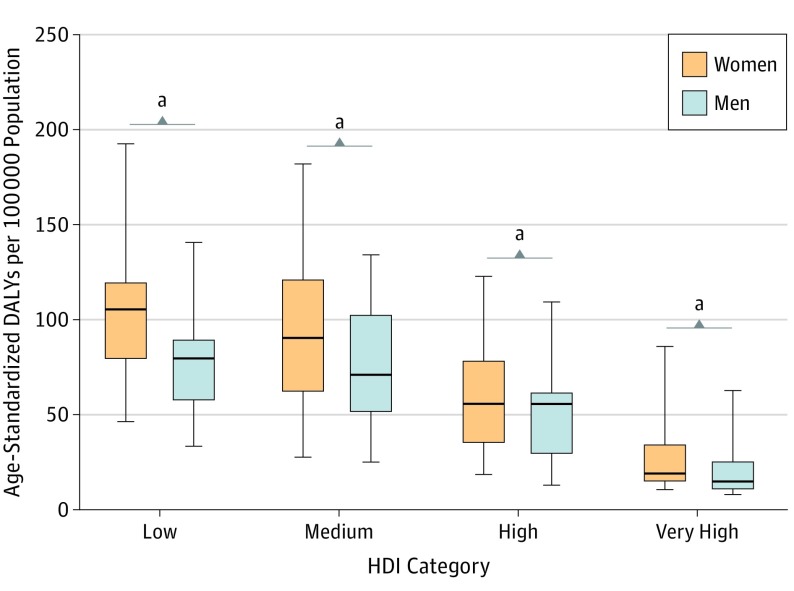

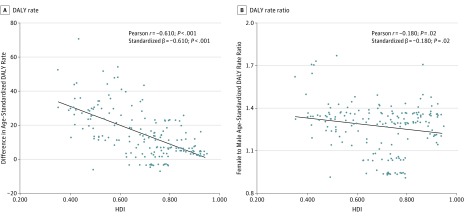

For 195 countries included in the GBD Study 2015, paired Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated that in 2015, women had higher age-standardized DALY rates than men (z = −11.125; P < .001), with median rates of 57.7 (interquartile range [IQR], 30.8-97.6) among women and 55.6 (IQR, 28.2-79.1) among men. The HDI data in 2015 were available for 184 countries, including 41 countries with low HDI, 41 with medium HDI, 53 with high HDI, and 49 with very high HDI. Age-standardized DALY rates among women were higher than those among men for low (105.7 [IQR, 80.2-119.5] vs 80.0 [IQR, 58.2-89.6]), medium (90.8 [IQR, 62.8-121.2] vs 71.2 [IQR, 52.1-102.7]), high (55.7 [IQR, 36.1-78.7] vs 56.4 [IQR, 30.1-61.8]), and very high (19.8 [IQR, 15.8-34.2] vs 15.2 [IQR, 11.8-25.6]) HDI countries (Figure 3). In general, higher age-standardized DALY rates were observed in lower HDI countries in both sexes. Differences by sex (female minus male) in age-standardized DALY rates were inversely associated with HDI in Pearson correlation analyses (r = −0.610; P < .001) and linear regression analyses (standardized β = −0.610; P < .001) (Figure 4A). Female to male age-standardized DALY rate ratios were also inversely associated with HDI in Pearson correlations (r = −0.180; P = .02) and linear regression analyses (standardized β = −0.180; P = .02) (Figure 4B). Both sets of analyses indicated greater differences in cataract rates by sex in countries with lower HDI.

Figure 3. Sex Difference in Age-Standardized Disability-Adjusted Life-year (DALY) Rates.

Rates are stratified by human development index (HDI; range, 0-1.000, with higher values indicating higher levels of socioeconomic development) as an indicator of national socioeconomic status. Lines inside the boxes indicate the medians; boxes, the 25% and 75% percentiles; and lines outside the boxes, the minimum and the maximum values.

aFor difference between sexes, P < .001, paired Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Figure 4. Male and Female Age-Standardized Rates.

The sex difference (female minus male) in age-standardized disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) rates and female to male age-standardized DALY rate ratio were inversely related to the level of national socioeconomic development, measured by the human development index (HDI; range, 0-1.000, with higher values indicating higher levels of socioeconomic development) as an indicator of national socioeconomic status. The lines indicate linear fit; data points, countries with corresponding HDIs and female minus male difference in age-standardized DALY rates or female to male age-standardized DALY rate ratios.

Discussion

This study revealed that sex differences in the global burden of cataract have persisted since 1990. Despite health progress in cataract in both sexes, differences in rates of cataract by sex showed little improvement through 2015, with a higher burden in women than in men. Worldwide, sex differences in cataract burden increased with age and was greater in countries with lower socioeconomic status.

A recent review by Ramke et al showed a decrease in the prevalence of blindness in both sexes in all regions of the world from 1990 to 2010. They also provided further population-level information disaggregated by sex, namely, that women were not only more likely to have cataract, but also less likely to get the care they needed than men. Several population-based surveys performed in Africa found that women had excess risk for blindness due to cataract. For example, the prevalence of blindness due to cataract among women in Central Ethiopia, Botswana, and Nigeria was 1.46-, 1.60-, and 1.50-fold higher, respectively, than that among men. Moreover, a systematic review including 86 studies revealed lower surgical coverage for cataract among women in most African countries. As a less developed region, Africa seemed to have a marked difference in cataract burden by sex, which was consistent with our findings.

Nevertheless, several studies conducted in some areas in China, Brazil, and Nepal did not find differences in cataract blindness by sex. Of 2 surveys conducted in India, one including 5158 participants showed that the sex difference was not significant, whereas the other including 42 722 participants supported the existence of sex differences. Inconsistent findings might be attributable to the area surveyed and the sample size. We have investigated the extent of differences in global burden of cataract by sex by using the most reliable data available, with findings supporting differences by sex at the global level. The greatest difference by sex was observed in the region of Southeast Asia. In the 3 most populous Southeast Asian countries, India, Indonesia, and Bangladesh, the differences by sex in terms of age-standardized DALY rates were much greater than that at the the global level (nation-specific data are found in the Global Health Data Exchange), a finding that is worth the attention of government officials and health policy makers.

In almost all societies, women tend to outlive men, resulting in larger numbers and proportions of older women than older men. Moreover, the imbalance in sex increases with age. At the global level, 86 men for every 100 women are 60 years or older, and 63 men for every 100 women are 80 years or older. Because the risk of cataract increases with age, longer life expectancy of women may partially contribute to higher cataract burden. Being male or female refers not only to biological differences but also to cultural or social ones. Courtright and Lewallen suggested that sex-defined social roles might have a direct effect on differences by sex in blindness due to cataract. Because of child and family care responsibilities resulting in less freedom to leave home, women may find that travel to a surgical facility is more difficult. Less educational attainment also hinders the ability of women to obtain enough health care information. Older women often have less access to paid employment and less financial decision-making authority. In developing countries, poor women do not have the ability to make an individual decision about their own health care. Furthermore, studies showed that women may hide their suffering and feel ashamed of asking for their families’ support, whereas men tend to express a strong desire for better vision. In some cases, women do not seem to perceive cataract as an illness or surgery as a necessity. A study conducted in the United States revealed that 20% to 29% of women 40 years and older who had eye diseases were unaware of any reason to seek eye care, which was a major barrier second only to cost. According to a recent report from the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, most countries failed to ensure access to cataract surgery service for most of the population, especially for those in less developed countries. These findings were in keeping with those of another review, which found that cataract surgical coverage remained a problem in most regions of the world, especially for the female population.

Limitations

This study was subject to the limitations of the GBD Study 2015, including statistical assumption and data sources, as detailed in the study reports. Bias might come from the use of aggregate data at a national level instead of district data, because geographic variations in DALY estimates may occur. Although this study provided a global view of differences in cataract burden by sex, the conclusions may not be applicable to a specific district. Because the GBD study will update annually, differences in global cataract burden by sex during the long term could be further explored.

Conclusions

This study revealed that although global health in cataract in both sexes is progressing, little improvement has been achieved in differences by sex. Women, especially those who are older and live in less developed countries, bear a higher burden of cataract than men. Owing to higher needs of cataract care in women, equal provision of eye care going forward will not correct the difference in cataract burden by sex. The findings of this study might raise awareness of differences in global cataract burden by sex and emphasize the importance of making sex-sensitive health policy to manage global vision loss caused by cataract.

eFigure. Trends in World Health Organization Regional Sex-Specific Age-Standardized DALY Rates Caused by Cataract From 1990 to 2015

References

- 1.Bourne RR, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. ; Vision Loss Expert Group . Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e339-e349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khairallah M, Kahloun R, Bourne R, et al. ; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study . Number of people blind or visually impaired by cataract worldwide and in world regions, 1990 to 2010. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(11):6762-6769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewallen S, Mousa A, Bassett K, Courtright P. Cataract surgical coverage remains lower in women. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(3):295-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonsson PM, Schmidt I, Sparring V, Tomson G. Gender equity in health care in Sweden—minor improvements since the 1990s. Health Policy. 2006;77(1):24-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtright P. Gender and blindness: taking a global and a local perspective. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2009;2(2):55-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ono K, Hiratsuka Y, Murakami A. Global inequality in eye health: country-level analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1784-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1603-1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries during 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545-1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Global Health Data Exchange GBD Results Tool. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. Posted October 2016. Accessed March 5, 2017.

- 10.United Nations Development Programme Human development report 2016: human development for everyone. http://www.hdr.undp.org/en/2016-report. Posted 2016. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- 11.Ramke J, Zwi AB, Palagyi A, Blignault I, Gilbert CE. Equity and blindness: closing evidence gaps to support universal eye health. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(5):297-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woldeyes A, Adamu Y. Gender differences in adult blindness and low vision, Central Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2008;46(3):211-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nkomazana O. Disparity in access to cataract surgical services leads to higher prevalence of blindness in women as compared with men: results of a national survey of visual impairment. Health Care Women Int. 2009;30(3):228-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdull MM, Sivasubramaniam S, Murthy GV, et al. ; Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Study Group . Causes of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria: the Nigeria national blindness and visual impairment survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(9):4114-4120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aboobaker S, Courtright P. Barriers to cataract surgery in Africa: a systematic review. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2016;23(1):145-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu M, Yip JL, Kuper H. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness in Kunming, China. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(6):969-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salomao SR, Cinoto RW, Berezovsky A, et al. Prevalence and causes of vision impairment and blindness in older adults in Brazil: the Sao Paulo Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(3):167-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherchan A, Kandel RP, Sharma MK, Sapkota YD, Aghajanian J, Bassett KL. Blindness prevalence and cataract surgical coverage in Lumbini Zone and Chetwan District of Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(2):161-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murthy GV, Vashist P, John N, Pokharel G, Ellwein LB. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and blindness in older adults in an area of India with a high cataract surgical rate. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17(4):185-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neena J, Rachel J, Praveen V, Murthy GV; Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness India Study Group . Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness in India. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regan JC, Partridge L. Gender and longevity: why do men die earlier than women? comparative and experimental evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(4):467-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations World population ageing report 2015. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/ageing/WPA2015_Infochart.shtml. Posted 2015. Accessed March 6, 2017.

- 23.Donaldson PJ, Grey AC, Maceo Heilman B, Lim JC, Vaghefi E. The physiological optics of the lens. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;56:e1-e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Courtright P, Lewallen S. Why are we addressing gender issues in vision loss? Community Eye Health. 2009;22(70):17-19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klasen S, Lamanna F. The impact of gender inequality in education and employment on economic growth: new evidence for a panel of countries. Fem Econ. 2009;15(3):91-132. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanda P. Gender dimensions of user fees: implications for women’s utilization of health care. Reprod Health Matters. 2002;10(20):127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mganga H, Lewallen S, Courtright P. Overcoming gender inequity in prevention of blindness and visual impairment in Africa. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2011;18(2):98-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Eye-care utilization among women aged > or =40 years with eye diseases–19 states, 2006-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(19):588-591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness Cataract surgical coverage. https://www.iapb.org/resources/cataract-surgical-coverage/. October 15, 2015. Accessed March 12, 2017.

- 30.Rao GN, Khanna R, Payal A. The global burden of cataract. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(1):4-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Trends in World Health Organization Regional Sex-Specific Age-Standardized DALY Rates Caused by Cataract From 1990 to 2015