Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) of colorectal liver metastases (CLM) is increasingly performed in specialized centers. While there is a trend towards a parenchyma-sparing strategy in multimodal treatment for CLM, its role is yet unclear. In this study we present short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic parenchyma-sparing liver resection (LPSLR) at a single center.

Patients and methods

LLR were performed in 951 procedures between August 1998 and March 2017 at Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway. Patients who primarily underwent LPSLR for CLM were included in the study. LPSLR was defined as non-anatomic hence the patients who underwent hemihepatectomy and sectionectomy were excluded. Perioperative and oncologic outcomes were analyzed. The Accordion classification was used to grade postoperative complications. The median follow-up was 40 months.

Results

296 patients underwent primary LPSLR for CLM. A single specimen was resected in 204 cases, multiple resections were performed in 92 cases. 5 laparoscopic operations were converted to open. The median operative time was 134 minutes, blood loss was 200 ml and hospital stay was 3 days. There was no 90-day mortality in this study. The postoperative complication rate was 14.5%. 189 patients developed disease recurrence. Recurrence in the liver occurred in 146 patients (49%), of whom 85 patients underwent repeated surgical treatment (liver resection [n = 69], ablation [n = 14] and liver transplantation [n = 2]). Five-year overall survival was 48%, median overall survival was 56 months.

Conclusions

LPSLR of CLM can be performed safely with the good surgical and oncological results. The technique facilitates repeated surgical treatment, which may improve survival for patients with CLM.

Key words: laparoscopic parenchyma-sparing liver resection, colorectal cancer, liver metastases, survival

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide.1 Liver resection is considered the only curative treatment for colorectal liver metastases (CLM), with postoperative 5-year survival rates of 30–58%.2, 3, 4, 5 Parenchyma-sparing liver resection (PSLR) has, in many centers, become an essential part of multimodal treatment of CLM. The parenchyma-sparing approach allows radical resection with maximum preservation of liver parenchyma, thereby decreasing the risk of postoperative liver failure and facilitating repeated resections in the case of liver recurrence.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

Laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) has progressively developed during the past two decades and the advantages are well-known.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Our experience in LLR has been reported previously.18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 The short- and long-term outcomes after laparoscopic parenchyma-sparing liver resection (LPSLR) for CLM have been minimally reported in the literature.28, 29, 30 In this study we report short and longterm outcomes after 18 years of LPSLR for CLM in a single center.

Patients and methods

Rikshospitalet is the tertiary referral center for hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery for the South-Eastern Regional Health Authority in Norway. Between August 1998 and March 2017, LLRs were performed in 951 procedures. Of these, patients who primarily underwent LPSLR for CLM between August 1998 and March 2016 were identified from the continuously updated database and included in the study. Patients who previously underwent open liver resections were excluded from the study. LPSLR was defined as non-anatomic laparoscopic liver resections. In one case LPSLR was performed in a patient with a transplanted liver. Patients who underwent hemihepatectomy or sectionectomy were excluded, as were patients with planned two-stage procedures. Data were collected from Electronic Health Records. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients signed informed consent for the procedures.

Standard preoperative investigations included contrast-enhanced X-ray computed tomography (CT) scans of the thorax and abdomen, clinical biochemistry, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver (if required) and positron emission tomography (PET) scan (if required).

Synchronous CLM was defined as liver metastases detected within 12 months of diagnosis of the primary CRC, otherwise metastases were defined as metachronous.

The surgical technique for LLR at our centre has been described previously.18, 19, 20, 21 Laparoscopic ultrasonography and advanced laparoscopic equipment were preconditions. The main dissection instruments were LigaSure® (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA), Thunderbeat® (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or Cayman® (B.Braun, Melsungen, Germany), sometimes assisted by ultrasonic aspirators, mainly CUSA® (Integra, Cincinnati, OH, USA), SonoSurg aspirator® (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and Söring aspirator® (Söring, Quickborn, Germany). Ultrasonic dissectors, as Sonicision® (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) or Harmonic Scalpel® (Ethicon, Sommerville, NJ, USA) were mostly used to achieve a superficial parenchymal transection. Surgical clips and the LigaSure® were used in small and medium-sized vessel transections, whereas the Endo-GIA®(Covidien, Inc.) was applied for transection of major vessels.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and intravenous paracetamol were used for postoperative analgesia. Opioids were given if required. Patients were encouraged to mobilize early and resume oral intake as soon as tolerated.

Tumor size was measured following specimen fixation in formaldehyde during the histopathologic analyses of resected specimens. The distance from the tumor to the resection margin was measured macroscopically and microscopically after fixation. All resection margins were assessed microscopically with regard to tumor tissue, a resection margin of less than 1 mm was defined as positive (R1). In cases where multiple resections were performed, the narrowest resection margin was recorded.

Postoperative complications were categorized in accordance to the Accordion classification.31, 32

Patients were treated with neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy following national guidelines. The data are presented as median (range) and/or number (percentage). Overall survival was estimated from liver resection until death and recurrence-free survival was estimated from liver resection until the first registered recurrence of the disease or progression in cases with extrahepatic metastases. Survival probabilities were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. SPSS software (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0, Armonk, NY, USA: IBM corp) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Perioperative data

Between August 1998 and March 2016, a total of 296 patients underwent LPSLR as the primary surgical treatment for CLM at Oslo University Hospital. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Resection of solitary metastases was performed in 204 patients (69%), multiple resections were performed in the remaining 92 patients (31%). Two concomitant liver resections were performed in 66 cases, three resections in 12 cases, four resections in 12 cases, five and seven resections in the two remaining cases. In total, 432 liver specimens were resected in 296 procedures. Median resection margin was 3 mm (range 0 to 30 mm). The total number of removed lesions was 448 and the median diameter was 22 mm (range: 4 to 80 mm). The resected tumors were located in all liver segments (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 296)

| Age, years, median (range) | 66 (29–89) |

| Gender (female/male) | 110/186 |

| BMI, kg, median, (range) | 25 (16–42) |

| ASA score | 2 (1–3) |

| Synchronous/metachronous | 224/72 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy yes/no/no information | 122/168/6 |

| Preoperative CEA, median (range) | 12 (1–498) |

| Extrahepatic disease at the time of liver resection, n (%) | 21 (7.1) |

| Liver involvement (unilobar/bilobar) | 233/63 |

ASA = American Society of Anestesiology; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcino-embryonic antigen

Table 2.

Intraoperative details and postoperative complications

| Operative time, min, median (range) | 134 (20-373) |

| Blood loss, ml, median (range) | 200 (<50-4000) |

| No. of resected specimens pr. procedure, 1/ 2/ 3/ 4/ 5/ 7 Total | 204/ 66/ 12/ 12/ 1/ 1 432 |

| Total No. of removed lesions | 448 |

| Max diameter of lesions, mm, median d (range) | 22 (4-80) |

| Resection margin, R0 / R1 (n=294) Median, mm (range) | 239 / 55 3 (0-30) |

| Conversion to open access, n (%) | 5 (1.7) |

| Combination with RFA or cryoablation, n (%) | 20 (6.7) |

| Simultaneous resection with primary, n (%) | 11 (3.7) |

| Postoperative complications, Accordion, n (%) Grade 2 / Grade 3 / Grade 4 / Grade 5 | 43 (14.5) 19/ 14/ 8/ 2 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, days, median (range) | 3 (1-35) |

RFA = Radiofrequency ablation

Five procedures (1.7%) were converted to open surgery. The reason for conversion was hemorrhage (n = 3), unfavorable location of tumor (n = 1) and small intestine perforation (n = 1). In 20 cases LPSLR was combined with ablation (n = 18) or cryoablation (n = 2). 11 patients underwent synchronous resections for colorectal cancer. Median operative time was 134 min (20–373), while median blood loss was 200 ml (<50–4000). Postoperative complications developed in 43 patients (14.5%) and were graded according to the expanded Accordion classification (Table 2). The median hospital stay was 3 days (range: 1–35). There was no 90-day mortality in this study. Perioperative adverse events are described in Table 2.

Long-term outcomes

Median observation time was 40 months (4 to 191). Twenty-one patients had extrahepatic metastases (16 with lung metastases, two with metastases on the peritoneum, two with the metastases in the brain and the lungs, and one with metastasis in the spine) at the time of liver resection.

Disease recurrence or progression of extrahepatic metastases occurred in 189 (64%) patients on a median follow-up of 6 months. Recurrence in the liver occurred in 146 (49.3%) patients with a median follow-up of 6 months, including 7 patients (2.3%) who experienced local recurrence. Isolated hepatic recurrences developed in 75 patients. The most common sites of recurrence were liver, lungs, peritoneum and brain. A total of 69 patients underwent repeated liver resections, of whom 43 had laparoscopic and 26 had open resections. Additionally, 14 patients underwent secondary radiofrequency ablation and two patients had liver transplantation for liver recurrences (Table 3).

Table 3.

Long-term outcomes

| Disease recurrence, n (%) | 189 (64) |

| Liver recurrence, n (%) | 146 (49.3) |

| Isolated liver recurrence, n (%) | 75 (25.3) |

| Recurrence in resection bed, n (%) | 7 (2.3) |

| Repeat liver resection, n (%) | 69 (23.3) |

| Secondary RFA, n (%) | 14 (4.7) |

| Median overall survival, months (95% confidential interval) | 56 (46-66) |

| 3-year overall survival rate, % | 68 |

| 5-year overall survival rate, % | 48 |

| 3-year recurrence-free survival rate, % | 36 |

| 5-year recurrence-free survival rate, % | 34 |

RFA = Radiofrequency ablation

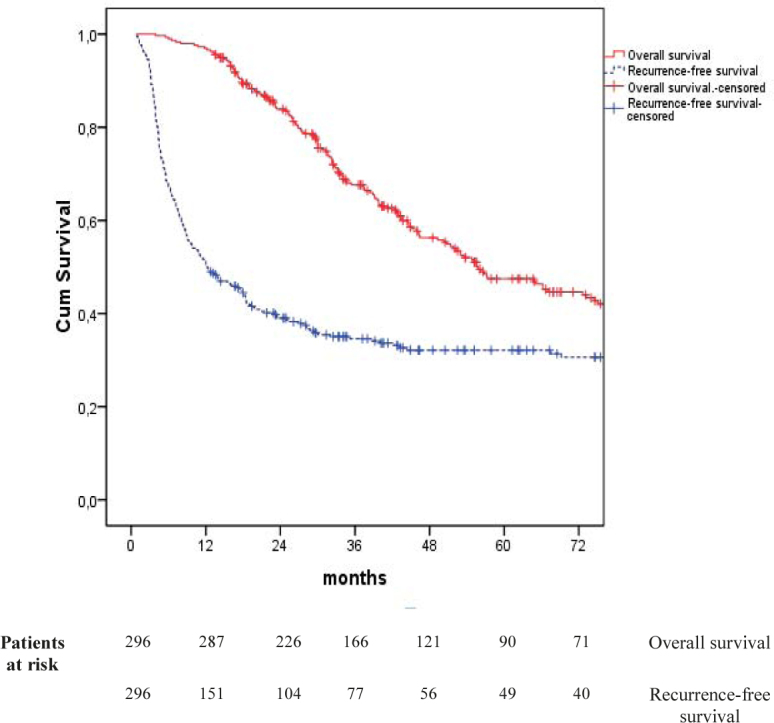

Median overall survival was 56 months One-, three- and five-year overall survival rates were 97%, 68% and 48%, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves

One-, three- and five-year recurrence-free survival was 50%, 36% and 34%, while the median recurrence-free survival was 12 months (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we report a single center experience of LPSLR for CLM. In 1960’s and 1970’s the majority of patients with CLM (70–80%) were never candidates for resection, but nowadays a large portion of patients undergo surgery due to significant improvements in preoperative investigations, surgical techniques, anesthesia, chemotherapy regimens and the expansion of resectability criteria.4, 5 Based on oncologic reasoning at that time, hemihepatectomies were considered the only curative option in patients with CLM. Nevertheless, over the years, PSLR has increasingly been used for CLM.6, 33 There are two main reasons for this: the evolution of the concept of resectability and the increased knowledge on tumor biology.34, 35

Over the past decades, the concept of tumor resectability in CLM has changed significantly. While in the 1970s, resection was considered only in patients with solitary liver metastasis, nowadays resection of CLM is considered regardless of tumor size and number, provided that a resection with negative margins is possible, that stable disease can be achieved, that the remaining parenchyma is sufficient to prevent liver failure, and that there is no unresectable extrahepatic disease.36

There are two known mechanisms for hepatic spread of colorectal cancer: metastasis from the primary tumor, and metastasis from other existing metastases. In contrast to hepatocellular carcinoma, tumor cells from CLM do not migrate into intrahepatic portal branches to form secondary intrahepatic metastases. Instead, intrahepatic lymphatic invasion can be responsible for “remetastasis” from liver metastases and may be a prognostic factor for CLM.37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42

PSLR is an essential part of multimodal treatment of CLM, as it avoids unnecessary removal of normal parenchyma and is associated with less surgical stress, fewer postoperative complications and feasibility of future resections.6, 33, 43

LLR is becoming an important alternative to conventional open surgery. In this study we included patients who primarily underwent LPSLR for CLM. All resections aimed to achieve complete tumor resection and to preserve as much liver parenchyma as possible. We report both perioperative and long-term oncologic outcomes. Five patients (1.7%) were converted to open surgery in our series, which is a lower conversion rate than reported for both minor and major laparoscopic hepatectomies by other groups.16, 28, 29, 44 Postoperative complications developed in 43 cases (14.5%) and the median postoperative length of stay was 3 days. Perioperative outcomes in this study are consistent with earlier reported surgical results after open and laparoscopic PSLR for CLM.7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 28, 29

Previous studies have indicated that survival rates were higher in patients with resection margins larger than 10 mm compared to those with the resection margins less than 10 mm.45, 46 Other studies have opposed these findings and indicate that predicted margins of less than 10 mm should not be an exclusion criteria for resection in these patients.40, 47 Moreover, recently two large studies suggested that a one mm cancer free margin can be considered oncologically adequate for resection of CLM.27, 48

In the present study, isolated hepatic recurrence developed in 75 cases, for which repeated hepatectomy was performed in 68% (51 of 75) (18 open, 33 laparoscopic). Local recurrence developed in seven patients (2.3%), five following R1 resection (9%) and two following R0 resection (0.8%). The relatively low number of local recurrences after R1 resections can be explained by the use of energy-based surgical instruments for parenchyma transection, that induce thermal damage to the surrounding tissue and thus create an additional zone of tissue necrosis. As a result, the true resection margins may be several millimeters wider than those estimated by the pathologist.

In our study liver recurrences were frequently resectable. A total of 69 repeat liver resections (51 with isolated liver recurrence and 18 with extrahepatic resectable metastases) were performed.

Tanaka et al.49 showed that minor resections may offer a long-term survival advantage compared to a major resection in patients with multiple CLM. In our study 80 patients received solely multiple LPSLR, and the five-year survival for this group was 44%.

In the study published in 2014, Evrard et al.50 combined PSLR with RFA in 288 patients, five-year overall survival was 37%, compared to 39% for the 18 patients that underwent resection combined with local ablation in our study.

These outcomes demonstrate that multiple simultaneous LPSLRs are feasible and may be preferred over single major resection in a substantial portion of patients. In patients with additional unfavorable located lesions, PSLR can be combined with local ablation avoiding formal resections with acceptable oncological results. In addition, the patients with formal resections compared with parenchyma-sparing technique have reduced chance of further surgical treatment.6

Alvarez et al.6 showed in a systematic review that five-year overall survival rates varied from 27% to 60% for anatomic and from 29% to 61% for non-anatomic liver resection, compared to 48% in our study.

In conclusion, outcomes after laparoscopic parenchyma-sparing liver resection are comparable to those after open major and minor hepatectomy. In centers with sufficient expertise, this may be a good treatment option for patients with CLM.

Footnotes

Disclosure: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curley SA. Outcomes after surgical treatment of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Sem Oncol. 2005;32(9):S109–11. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, O’Rourke T, John TG. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:125–35. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815aa2c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiappa A, Makuuchi M, Lygidakis NJ, Zbar AP, Chong G, Bertani E. et al. The management of colorectal liver metastases: Expanding the role of hepatic resection in the age of multimodal therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;72:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmonds PC, Primrose JN, Colquitt JL, Garden OJ, Poston GJ, Rees M. Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published studies. Brit J Cancer. 2006;94:982–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez FA, Sanchez Claria R, Oggero S, de Santibanes E. Parenchymal-sparing liver surgery in patients with colorectal carcinoma liver metastases. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:407–23. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuki R, Mise Y, Saiura A, Inoue Y, Ishizawa T, Takahashi Y. Parenchymal-sparing hepatectomy for deep-placed colorectal liver metastases. Surgery. 2016;160:1256–63. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumura M, Mise Y, Saiura A, Inoue Y, Ishizawa T, Ichida H. et al. Parenchymal-sparing hepatectomy does not increase intrahepatic recurrence in patients with advanced colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3718–26. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Memeo R, de Blasi V, Adam R, Goere D, Azoulay D, Ayav A. et al. Parenchymal-sparing hepatectomies (PSH) for bilobar colorectal liver metastases are associated with a lower morbidity and similar oncological results: a propensity score matching analysis. HPB. 2016;18:781–90. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mise Y, Aloia TA, Brudvik KW, Schwarz L, Vauthey JN, Conrad C. Parenchymal-sparing hepatectomy in colorectal liver metastasis improves salvageability and survival. Ann Surg. 2016;263:146–52. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold JS, Are C, Kornprat P, Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y. et al. Increased use of parenchymal-sparing surgery for bilateral liver metastases from colorectal cancer is associated with improved mortality without change in oncologic outcome: trends in treatment over time in 440 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:109–17. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181557e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kokudo N, Tada K, Seki M, Ohta H, Azekura K, Ueno M. et al. Anatomical major resection versus nonanatomical limited resection for liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2001;181:153–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00560-2. PubMed PMID: 11425058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzzetti E, Pulitano C, Catena M, Arru M, Ratti F, Finazzi R. et al. Impact of type of liver resection on the outcome of colorectal liver metastases: a case-matched analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:503–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.20979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reich H, McGlynn F, DeCaprio J, Budin R. Laparoscopic excision of benign liver lesions. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:956–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buell JF, Cherqui D, Geller DA, O’Rourke N, Iannitti D, Dagher I. et al. The international position on laparoscopic liver surgery: The Louisville Statement, 2008. Ann Surg. 2009;250:825–30. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181b3b2d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy SK, Tsung A, Geller DA. Laparoscopic liver resection. World J Surg. 2011;35:1478–86. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0906-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakabayashi G, Cherqui D, Geller DA, Buell JF, Kaneko H, Han HS. et al. Recommendations for laparoscopic liver resection: a report from the second international consensus conference held in Morioka. Ann Surg. 2015;261:619–29. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwin B, Mala T, Gladhaug I, Fosse E, Mathisen Y, Bergan A. et al. Liver tumors and minimally invasive surgery: a feasibility study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:133–9. doi: 10.1089/10926420152389260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherqui D, Husson E, Hammoud R, Malassagne B, Stephan F, Bensaid S. et al. Laparoscopic liver resections: a feasibility study in 30 patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232:753–62. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen KT, Gamblin TC, Geller DA. World review of laparoscopic liver resection-2, 804 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:831–41. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b0c4df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mala T, Edwin B, Rosseland AR, Gladhaug I, Fosse E, Mathisen O. Laparoscopic liver resection: experience of 53 procedures at a single center. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:298–303. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-0974-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazaryan AM, Marangos IP, Rosok BI, Rosseland AR, Villanger O, Fosse E. et al. Laparoscopic resection of colorectal liver metastases: surgical and long-term oncologic outcome. Ann Surg. 2010;252:1005–12. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f66954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazaryan AM, Pavlik Marangos I, Rosseland AR, Rosok BI, Mala T, Villanger O. et al. Laparoscopic liver resection for malignant and benign lesions: tenyear Norwegian single-center experience. Arch Surg. 2010;145:34–40. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barkhatov L, Fretland AA, Kazaryan AM, Rosok BI, Brudvik KW, Waage A. et al. Validation of clinical risk scores for laparoscopic liver resections of colorectal liver metastases: a 10-year observed follow-up study. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:757–63. doi: 10.1002/jso.24391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwin B, Nordin A, Kazaryan AM. Laparoscopic liver surgery: new frontiers. Scand J Surg. 2011;100:54–65. doi: 10.1177/145749691110000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazaryan AM, Rosok BI, Marangos IP, Rosseland AR, Edwin B. Comparative evaluation of laparoscopic liver resection for posterosuperior and anterolateral segments. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3881–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1815-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Postriganova N, Kazaryan AM, Rosok BI, Fretland A, Barkhatov L, Edwin B. Margin status after laparoscopic resection of colorectal liver metastases: does a narrow resection margin have an influence on survival and local recurrence? HPB. 2014;16:822–9. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cipriani F, Shelat VG, Rawashdeh M, Francone E, Aldrighetti L, Takhar A. et al. Laparoscopic parenchymal-sparing resections for nonperipheral liver lesions, the diamond technique: technical aspects, clinical outcomes, and oncologic efficiency. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conrad C, Ogiso S, Inoue Y, Shivathirthan N, Gayet B. Laparoscopic parenchymal-sparing liver resection of lesions in the central segments: feasible, safe, and effective. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2410–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3924-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Hondt M, Yoshihara E, Vansteenkiste F, Steelant PJ, Van Ooteghem B, Pottel H. et al. Laparoscopic parenchymal preserving hepatic resections in semiprone position for tumors located in the posterosuperior segments. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401:255–62. doi: 10.1007/s00423-016-1375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:177–86. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181afde41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porembka MR, Hall BL, Hirbe M, Strasberg SM. Quantitative weighting of postoperative complications based on the accordion severity grading system: demonstration of potential impact using the american college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:286–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moris D, Dimitroulis D, Vernadakis S, Papalampros A, Spartalis E, Petrou A. et al. Parenchymal-sparing hepatectomy as the new doctrine in the treatment of liver-metastatic colorectal disease: beyond oncological outcomes. Anticancer Res 2017. 37:9–14. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams RB, Aloia TA, Loyer E, Pawlik TM, Taouli B, Vauthey JN. Selection for hepatic resection of colorectal liver metastases: expert consensus statement. HPB. 2013;15:91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riihimaki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Scientific Rep. 2016;6:29765. doi: 10.1038/srep29765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin K, Gao W, Lu Y, Lan H, Teng L, Cao F. Mechanisms regulating colorectal cancer cell metastasis into liver (Review) Oncol Lett. 2012;3:11–5. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kokudo N, Miki Y, Sugai S, Yanagisawa A, Kato Y, Sakamoto Y. et al. Genetic and histological assessment of surgical margins in resected liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma: minimum surgical margins for successful resection. Archives Surg. 2002;137:833–40. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.7.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pawlik TM, Scoggins CR, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Andres A, Eng C. et al. Effect of surgical margin status on survival and site of recurrence after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2005;241:715–22. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000160703.75808.7d. discussion 22-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lupinacci RM, Mello ES, Pinheiro RS, Marques G, Coelho FF, Kruger JA. et al. Intrahepatic lymphatic invasion but not vascular invasion is a major prognostic factor after resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases. World J Surg. 2014;38:2089–96. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korita PV, Wakai T, Shirai Y, Sakata J, Takizawa K, Cruz PV. et al. Intrahepatic lymphatic invasion independently predicts poor survival and recurrences after hepatectomy in patients with colorectal carcinoma liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3472–80. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fretland AA, Sokolov A, Postriganova N, Kazaryan AM, Pischke SE, Nilsson PH. et al. Inflammatory response after laparoscopic versus open resection of colorectal liver metastases: data from the Oslo-CoMet Trial. Medicine. 2015;94 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearce NW, Di Fabio F, Teng MJ, Syed S, Primrose JN, Abu Hilal M. Laparoscopic right hepatectomy: a challenging, but feasible, safe and efficient procedure. Am J Surg. 2011;202 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Are C, Gonen M, Zazzali K, Dematteo RP, Jarnagin WR, Fong Y. et al. The impact of margins on outcome after hepatic resection for colorectal metastasis. Ann Surg. 2007;246:295–300. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31811ea962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wakai T, Shirai Y, Sakata J, Valera VA, Korita PV, Akazawa K. et al. Appraisal of 1 cm hepatectomy margins for intrahepatic micrometastases in patients with colorectal carcinoma liver metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2472–81. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamady ZZ, Cameron IC, Wyatt J, Prasad RK, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP. Resection margin in patients undergoing hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastasis: a critical appraisal of the 1cm rule. EJSO. 2006;32:557–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamady ZZ, Lodge JP, Welsh FK, Toogood GJ, White A, John T. et al. One-millimeter cancer-free margin is curative for colorectal liver metastases: a propensity score case-match approach. Ann Surg. 2014;259:543–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182902b6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka K, Shimada H, Matsumoto C, Matsuo K, Takeda K, Nagano Y. et al. Impact of the degree of liver resection on survival for patients with multiple liver metastases from colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2008;32:2057–69. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9610-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evrard S, Poston G, Kissmeyer-Nielsen P, Diallo A, Desolneux G, Brouste V. et al. Combined ablation and resection (CARe) as an effective parenchymal sparing treatment for extensive colorectal liver metastases. PloS One. 2014;9:e114404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]