Abstract

Objective(s)

People Living with HIV (PLHIV) on anti-retroviral treatment (ART) who drink are less adherent and more likely to engage in unprotected sex. Using an adapted Timeline Follow-Back (A-TLFB) procedure, this paper examines the day by day interface of alcohol, medication adherence and sex to provide a fine grained understanding of how multiple behavioral risks coincide in time and space, explores concordance/discordance of measures with survey data and identifies potential recall bias.

Methods

Data are drawn from a survey of behavior, knowledge and attitudes, and a 30 day TLFB assessment of multiple risk behaviors adapted for the Indian PLHIV context, administered to 940 alcohol-consuming, HIV positive men on ART at the baseline evaluation stage of a multilevel, multi-centric intervention study

Results

On days participants drank they were significantly more likely to be medication non-adherent and to have unprotected sex. In the first day after their alcohol consuming day, the pattern of nonadherence persisted. Binge and regular drinking days were associated with nonadherence but only binge drinking co-occurred with unprotected sex. Asking about specific “drinking days” improved recall for drinking days and number of drinks consumed. Recall declined for drinking days and nonadherence from the first week to subsequent weeks but varied randomly for sex risk. There was high concordance and low discordance between adapted TLFB drinking and nonadherence but these results were reversed for unprotected sex.

Conclusions

Moving beyond simple drinking-adherence correlational analysis, the adapted TLFB offers improved recall probes and provides researchers and interventionists with the opportunity to identify types of risky days and tailor behavioral modification to reduce alcohol consumption, nonadherence and risky sex on those days.

Keywords: Timeline Followback, alcohol, ART adherence, sexual risk, India

Introduction

Alcohol consumption is highly correlated with negative physical and mental health status in people living with HIV (1–6). Alcohol consumption has been shown to decrease immunological function (7), and increase viral replication (8, 9). It can interfere with the metabolism of ART medication (10), amplify ART toxicity (2) contribute to disease progression(11–13), impairment of memory and concentration (14), inconsistency in the performance of health related behaviors such as sleeping and eating (15), and can create conflicts with caregivers and medical providers (16) affecting the HIV continuum of care (17).

A high degree of adherence (> 95%) to ART is critical in maintaining low viral load in individuals (18) and in preventing the continued spread of the HIV virus to sexual partners and others (19). Researchers have shown that alcohol, even at the sub-intoxication level, affects medication adherence (10, 20) through skipping or postponing medication to avoid concurrence with drinking, forgetting to take medication, (21, 22) and failure to renew medication on schedule.

It is now well established that alcohol consumption has a significant impact on risky sex involving unprotected sex with seronegative sex partners, extramarital sex, visits to commercial sex workers and coercive and/or forceful sex (23–27). Alcohol consumption is associated with lowering of sexual inhibition and places individuals in situations and locations such as bars, brothels and hotels where risky sexual behavior is accessible. These circumstances and behaviors can result in seroconversion of sex partners and super infection for the PLHIV and the seropositive sex partner (28). To prevent these consequences, further efforts are required to understand the dynamics of alcohol, its association with adherence and its influence on the risk of HIV transmission in people living with HIV who consume alcohol and are on ART medication.

India has the third highest number of PLHIV in the world, with approximately 2.1 million people infected (29). In 2004 India introduced free provision of ART through government run ART centers and at the present time, the existing centers are able to serve approximately 35% of those needing treatment (30). One of the primary factors fueling the HIV epidemic in India is alcohol consumption (31). For the past 20 years, alcohol marketing, sales and consumption have climbed rapidly and drinking preferences have shifted to alcohol with higher ethanol content per standard drink, primarily from Indian-produced whiskey (32–34). Drinking, especially the consumption of larger amounts of alcohol has been shown to be associated with health impacts (35) and unprotected sex (26) and sexually transmitted infections and HIV in mobile workers, married and unmarried men with multiple partners, and female sex workers in India (24, 26, 27, 36). Men are the primary consumers of alcohol and among Indian PLHIV, twenty times more men than women consume alcohol (37). Reducing or eliminating male PLHIV alcohol use can result in greater medication adherence and a decrease in unprotected sex as well as in HIV transmission.

A key issue in research and intervention is the effective measurement of alcohol consumption. Better measurement can allow for more precise assessment of levels of consumption in relation to key elements of transmission risk, especially nonadherence and unprotected sex (38). A typical measure of alcohol consumption is based on items or scales that identify and combine patterns of drinking (e.g. the AUDIT-C, a short form of the AUDIT instrument, which includes frequency of drinking in past 30 days, number of drinks on a typical occasion, and frequency of binge drinking)(39–41). The AUDIT-C and similar measures indicate whether or not, based on situation specific or standardized cutoff points, individuals are low, moderate or hazardous drinkers, and linked to different levels of intervention (40).

A second approach consists of scales that identify problem drinking (e.g. the AUDIT) that include both amount/pattern of drinking and validated indicators of problem drinking such as being told to quit drinking by others and memory gaps) (42, 43). These measures may serve the same purpose as quantity/frequency measures, but provide more information on behavioral consequences of drinking that are useful in intervention (42, 44).

The third type of measure combines the AUDIT and AUDIT-C with a more accurate count of pure alcohol consumed and is useful especially in studies that strive for more precise assessments of pure alcohol quantity consumed (24, 45–47). These measures multiply types of alcohol consumed, numbers of drinks consumed of each type on each day or on average by amount of alcohol in a standard drink times the number/type of alcohol standard drinks consumed times days consumed or averaged across standardized periods of time. These three types of measures can all be readily included in surveys and they all tend to show that more alcohol consumption is associated with higher levels of risk behavior including medication adherence, and unprotected sex (36, 48, 49).

A fourth type of measure, the Timeline Followback (TLFB) procedure, developed by Sobel (4–6), represents a method of establishing more accurate estimates of alcohol consumption using retrospective recall that can, at the same time, identify specific patterns of drinking such as sequencing or repetitive intermittent (e.g. weekend) drinking that may lead to more tailored approaches to alcohol risk reduction interventions (50). The usual TLFB procedure calls for anchoring recall of days, types and amounts of alcohol consumed against special events typically over the course of 30 days. Results can be crosschecked with other measures of alcohol consumption such as the AUDIT and with prospective approaches to collection of alcohol consumption data. Such comparisons have generally showed that the TLFB is consistent with both and can be used interchangeably with prospective diaries, interactive voice response phone messaging (IVR) or the AUDIT (51–54). The TLFB procedure is time consuming, however, as it requires considerable probing to ensure that recall is as accurate as possible over each day during the 30, 60 or 90 day recall period. Thus cost of administration must be weighed against the benefits of value-added information provided by a daily recounting of alcohol consumed.

One reported benefit of TLFB use is the identification of patterns of consumption and non-consumption over the course of the designated period. Understanding variations in sequencing and clustering of drinking events can make a difference both in clinical counseling and in obtaining greater measurement precision in determining how the timing of alcohol consumption, the amount consumed and specific drinking behaviors intersect over the course of a 30 day period. The TLFB can show for example on which weekend or week days more drinking is likely to take place; and can identify the total number of standard drinks (and associated ethanol consumption) consumed each day. It can also differentiate the pattern of consumption of different types of alcohol over the course of a week or month for both individuals and study populations (e.g. beer during the week, whiskey on weekends).

A second benefit addresses greater specificity in examining the association of alcohol consumption and other risk behaviors. Correlational studies generally show that greater amounts of alcohol consumption are associated with higher levels of risk behavior but do not provide information on the details or chronology of those associations. (27, 36, 55). Depending on the recall details required (e.g. specific types of alcohol, specific types of partners, complete or partial nonadherence), the TLFB permits a more fine grained analysis of patterns of drinking including combinations of timing, sequencing and amounts as related to other variables measuring key predictors and consequences of alcohol use among PLHIV (56).

Many of the key risk variables that are important in measuring HIV related health status and health outcomes among PLHIV are, like alcohol, temporal, patterned and irregular or intermittent in occurrence. To assess fully the impact of alcohol on the key variables of medication adherence and sexual risk, the TLFB comes closest to determining “causality” through same or proximate day co-occurrence. Toward this end, this paper describes an adapted Timeline Followback procedure (A-TLFB) that includes day by day 30 day recall for alcohol consumption, medication adherence and unprotected sex. The paper will review frequencies for alcohol consumption by day and by alcohol type, as well as frequencies for medication nonadherence and unprotected sex. It will then compare these frequencies to results obtained in a general survey calling for alcohol consumption estimates through the AUDIT, four day and seven day adherence and unprotected sex counts for past 30 days and 3 months (for nonspousal partners). Next we examine same day and second day co-occurrence of alcohol with risky behaviors (nonadherence and unprotected sex). The paper then turns to the relative merit of using anchoring against asking for special drinking days as an effective recall probe in the India context. Finally it explores patterns of recall for the study’s three main risk variables - alcohol consumption, nonadherence and unprotected sex - to reveal patterns of potential recall bias for Indian male PLHIV in treatment over a 30 day period.

Methods

Study sites and participants

Baseline survey and viral load data were collected from 940 participants in an intervention study conducted in five government administered ART treatment sites, three in the Mumbai municipality associated with tertiary teaching hospitals, and two in the greater Mumbai area associated with district hospitals. Participants were recruited from each of the centers and screened for study eligibility. Eligibility criteria included age (18 and over), six or more months on ART medication and one or more drinks of alcohol in the past 30 days and being in good health (i.e. able to pick up medications every month). Eligibility was determined utilizing a brief, anonymous screener. 9954 ART patients were screened, and of these about 20% (1792) met eligibility criteria; of these approximately 32% (573) declined to enroll in the study. Of those remaining eligible, 188 participants were recruited from each center, consented, enrolled in the study and administered a baseline survey which included information on CD4 count from the medical record, and a viral load test. Of the 940 enrolled participants, 18 were surveyed more than 30 days after they completed the screener and did not report drinking any alcohol in the prior 30 days. They were eliminated from the sample, leaving 922 30-day drinkers for inclusion in the analyses for this paper. The study was approved by the Indian Council for Medical Research, the National AIDS Control Organization and the IRBs of the University of Connecticut, the International Center for Research on Women, Population Council and the IRBs of the tertiary hospitals that participated in the study.

Measures

Baseline Survey as Source of Measures

The baseline survey included detailed questions on prescribed ART medications and four and seven day adherence, and sexual behavior with spouse and/or regular partner. It also included the full AUDIT as well as AUDIT-C reported 30 day drinking of specific types of alcohol typical consumed in the study population. Additional questions on the survey included assessments of social support, internal and external stigma, mental health, quality of life and ART Center service satisfaction and other topics not addressed here.

The survey included the Adapted Timeline Followback Instrument which followed earlier questions on alcohol consumption, adherence and sexual risk. The 30 day A-TLFB included details about specific types of alcohol drunk and number of standard drinks of each type of alcohol on each day, days of nonadherence and days of unprotected sex with marital and other partners. Research investigators were given a laminated set of photos of five types of standard drinks in typical Indian containers (whiskey, country liquor, wine, regular beer and strong beer) plus instructions to anchor the 30 days with special days of any kind (festivals, birthdays, pujas, fast days,). They were trained to obtain information on drinking, nonadherence and unprotected sex beginning with adherence. They were given scripted questions to ask about any non-adherent days in past four days, past seven days and remaining 3 weeks, using the calendar as a visual. Next they were asked to identify drinking days in past four days, past seven days and remaining three weeks. For each drinking day they asked how many standard drinks of each of five types of alcohol were consumed. The interviewers then asked if there were any special drinking days and completed the same details for those special drinking days. Lastly, they asked about any unprotected sex in past four and seven days and remaining 3 weeks of the month, paralleling the recall times for questions about adherence and alcohol in the general survey. These data provided specific information on total alcohol consumption, days of drinking, nonadherence and unprotected sex and their overlap for the four day, seven day and the entire 30 day period and an accurate calculation of total number of standard drinks consumed on each drinking day, yielding drinking patterns, sequences and recall patterns over time. In this paper, the main independent variables include alcohol use, alcohol amount and types of drinkers (binge, regular and irregular and low and high binge dependent variables) and the dependent variables are nonadherence and unprotected sex with any partner.

Alcohol-related indicators: A-TLFB and Survey

Overall alcohol consumption was measured by number of standard drinks in total across 30 days, and mean number of standard drinks a day over past 30 days. Total ethanol consumption was measured by self-reported total number of standard drinks over 30 days times total ethanol content per standard drink. Binge drinkers were defined as drinking five or more drinks at a sitting at least once in 30 days. Non-binge drinkers were defined as those who drank less than five drinks on a given day regardless of their other drinking. Days of binge drinking were summed over 30 days to provide a 30 day total of number of binge drinking days per person. Binge drinkers were divided into two groups: higher level (5 binge days a month or more) and lower level (four binge days or less). Regular drinkers were defined as those with no binge drinking days and more than four days of alcohol use in past 30 days. Irregular drinkers were defined as those with no binge drinking days and four or less days of alcohol use in the past 30 days. Baseline survey equivalents were drawn from the first three questions of the AUDIT (the AUDIT C) that included estimated days of drinking in past 30 days, typical number of drinks on a drinking day, and number of times in 30 days that respondents drank 5–6 drinks or more at a time (binge drinking).

Nonadherence Indicators: A-TLFB and Survey

In the A-TLFB Nonadherence to ART was assessed with four and seven day questions and 30 day recall. Optional responses for adherence were full adherence (100% of prescribed 30 day doses; partial adherence (>/= 95% and < 100%, of prescribed 30 day doses; and non-adherence (< 95% of prescribed doses). These responses were grouped into two categories: full adherence (100% of prescribed 30 day doses) and nonadherence (<100% of prescribed doses) for each day and averaged across all 30 days to create a daily rate.

From the Baseline survey three self-reported adherence measures were used: an Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) 4-day recall adherence instrument (57), and a single question asking about number of days of missed doses in past seven days. In the Baseline survey, adherence was calculated as the percentage of doses taken over those prescribed over the past four days. Nonadherence was calculated as total number of doses missed/total number of doses prescribed in past four days.

Unprotected Sex Indicators: A-TLFB and Survey

Unprotected sex was assessed by two self-reported measures of sexual behaviors. In the A- TLFB, participants were asked for each of the 30 days whether they had sex and if a condom was used on each of these occasions. Participants were categorized as either having unprotected or protected sex on a given day for each of the past 30 days. An unprotected sex ratio was determined by the total number of instances of unprotected sex over the total number of times sex occurred in the past 30 days. In the Baseline survey, participants were asked the number of times they had sex and did not use condoms in the past one month (for spouse) or 3 months (for a partner that was not their spouse). Risky sex was calculated by dividing the total number of sex acts without condom use by the total number of sex acts and prorated by one third for partners.

Alcohol and risk behavior concurrence

To measure the specific overlap of alcohol consumption and medication adherence on the day they drank or did not drink, two variables were combined (e.g. drinking and adherence, nondrinking and adherence). As a result, four new variables combining drinking and adherence were created for each scenario: 1. Drinking and adherence; 2. Drinking and nonadherence; 3. Nondrinking and adherence and 4. Nondrinking and nonadherence.

Similarly, to measure the specific overlap of alcohol consumption and unprotected sex on drinking and nondrinking days, two variables were combined to create four new variables: 1 drinking and protected sex; 2. Drinking and unprotected sex; 3. Nondrinking and protected sex; and 4. Nondrinking and unprotected sex. All measures are summarized in Table VIII in the Appendix.

Recall pattern

To examine recall, we measured drinking, nonadherence and unprotected sex in four seven-day periods over 28 days. We excluded the last two to three days of every month to enable standardizing the comparison by seven day period or week. To assess pattern of consumption of alcohol over time, the mean number of standard drinks per week was defined as the total number of standard drinks per day for each seven day period, divided by number of drinking participants. The mean number of non-adherents to ART medication per week was defined as the proportion of doses missed during 1-week period over doses prescribed/participants. The proportion of unprotected sex events was defined as the number of times a condom was not used divided by the total number of sex acts during the respective periods.

Data concordance/disconcordance

Data concordance/discordance was assessed between survey variables that included AUDIT, AUDIT-C, four and seven day adherence and the overall count of sex acts for one month (spouse) and three month (regular partner) and the adapted TLFB variables of 30 day alcohol consumption, medication adherence and unprotected sex.

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted on the study sample of 922 participants to describe the types of drinkers, standard drinks for each day and frequency of consumption of different types of alcohol. Parametric tests were used for normally-distributed outcome variables and non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney and Wilcoxon rank sum test and Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient) were used for non-normally distributed outcome variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare mean standard drinks consumed by different types of drinkers (binge, regular and irregular). A post-hoc Tukey HSD was used to identify differences when ANOVAs showed significant differences among types of drinkers. Chi-square test was used to investigate the association between different types of drinkers and risky sex. The non-paramedic Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the differences between higher level binge drinkers and lower level binge drinkers. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare within subjects for the ratio of medication adherence with drinking to adherence without drinking and the ratio of risky sex with drinking to risky sex without drinking. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs) was used to measure the strength of association between total numbers of times of unprotected sex in TLFB versus total number of times of unprotected sex in general survey. The agreement between TLFB and survey variables was measured using the Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance with two-tailed probability for statistical significance. Finally, a logistic regression was used to investigate relationship between nonadherence and alcohol consuming levels, adjusting for age, education, marital status and employment. All results were considered significant if the p value was <.05.

Results

Demographics

Mean age of the study sample was 43 years, and mean education level was 7.5 years, though 12.2 % of the population had 12 years or more of education indicating that free and safe medication provided in government ART centers has also attracted middle class individuals. Thirty nine percent were born in Mumbai and 61% were born outside of Mumbai, arriving as migrants. Eighty percent (732) are currently married. Most were Hindu (87.3% or 821) and the rest Muslim, Buddhist and Christian (12.7%). Ninety-two percent (868) were currently employed either full or part time. The average number of months since HIV diagnosis was 68 and average length of time since starting ART was approximately 4.5 years. A previously published analysis showed no significant differences between those deemed eligible who declined to join the study and those who joined. (37)

Alcohol consumption

In the A-TLFB, respondents were asked for each of the 30 day about their consumption of five different types of alcohol typically drunk in Mumbai slum communities: regular and strong (higher alcohol content) beer, whiskey, wine, home brew or country liquor, referred to as “desi daaru” in Hindi. Results are reported in Table I below.

Table I.

Type and Quantity of Alcohol Drunk by Study Population

| Alcohol Type | TLFB n=922 (%) | No. of standard drinks/30 days for total population drinking alcohol type |

|---|---|---|

| English liquor | 604 (65.5) | 1148 |

| Country liquor (desi daaru | 152 (16.5) | 1195 |

| Wine | 19 (2.1) | 119 |

| Light beer | 79 (8.6) | 127 |

| Strong beer | 229 (24.8) | 894 |

| 1083* | ||

| 1083* |

Indicates that approximately 161 people were polyalcohol consumers, drinking more than one type of alcohol over the past 30 days.

Primary alcohol preferences were whiskey and strong beer; over a 30 day period, 17.5% (N=1083–922 =161) were polyalcohol consumers, drinking two or more types of alcohol. Only a few participants drank more than one type of alcohol on a single day. Baseline survey data showed that the mean age of initiation was approximately the same (22.5 years) for four types of alcohol, English liquor country liquor, regular beer and strong beer, while for the smaller number of wine drinkers, mean age of initiation (26.6 years) was higher.

Overall, 922 participants drank from 1–30 days a month. More than half (56.9%) drank only 1 or 2 days a month (n=525). 24.3% (n=224) drank 3 – 4 days a month (approximately once per week). Of the total sample, 18.8% (n=173) reported five drinking days or more a month (Table II).

Table II.

Frequency of drinking days for the 30 day period

| Number of days | Number of participants | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1 – 2 days | 525 | 56.9 |

| 3 – 4 days | 224 | 24.3 |

| 5 or more days | 173 | 18.8 |

| Total | 922 | 100 |

The average standard daily drink over a 30 day period provides a way of identifying high to low level drinkers and “binge” or hazardous drinkers. Table III below summarizes frequencies for the average number of standard drinks consumed each day in the past 30 days. Most of the sample consumed a mean of one drink or less each day over the 30 day period. However about 8% consumed a minimum of one drink each day, and 1.5% binged (5 or more drinks) every single day.

Table III.

Average standard drinks consumed each day in the past 30 days

| Standard drink | Frequency | Percent | Gm. Ethanol consumed |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 | 846 | 90.0 | 3356.78 gm |

| > 1 and ≤ 2 | 54 | 4.3 | 782.88 gm |

| > 2 and ≤ 3 | 16 | 1.7 | 538.86 gm |

| >3 and <5 | 6 | 0.6 | 268.38 gm |

| 5 and more | 14 | 1.5 | 1083.6 gm |

Binge drinking

Over sixty nine percent (n=642) of drinkers did not binge drink at all, that is, when they drank they never drank more than four drinks at a sitting. For the 30.4% (n=280) that did binge drink at least one day in the previous 30 days, Figure 1 below shows the number of binge-drinking days by participant.

Figure I.

Number of binge drinking days for each participant in the past 30 days (n=280)

Among binge drinkers, the number of binge drinking days varied from one day to every day; 22% (n=208) binged once to four times a month (drank five drinks or more at a sitting once a week or less), 8% (n=72) binged (drank) more than 5 drinks at a sitting) from five to 30 days each month.

In an effort to understand the effect of drinking patterns on risk behavior, we further disaggregated our sample into high and lower level binge drinkers, and regular and irregular drinkers to evaluate drinking pattern (see Table IV).

Table IV.

Frequencies for types of drinkers

| Type of Drinker | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular drinkers | 569 | 61.7 | |

| Regular drinkers | 73 | 7.9 | |

| Binge drinkers | 280 | 30.4 | |

| Total | 922 | 100.0 | |

| Binge drinkers | |||

| High level | 72 | 25.7 | |

| Low level | 208 | 74.3 | |

| Total | 280 | 100.0 | |

A one way ANOVA showed that there was a significant association between drinking pattern and the total amount of alcohol consumption in grams (F (2, 919)=117. 4, p<0.001). A post hoc Tukey test showed that binge drinkers consumed a significantly higher amount of alcohol in grams over 30 days (Mean=448.5) than regular (Mean=327.4) (p =.022) and irregular drinkers (Mean=66.6) (p<0.001) and that regular drinkers consumed a significantly higher amount of alcohol than irregular drinkers (p<0.001). A Mann-Whitney test showed that the total amount of alcohol consumption among higher level (5 + days) binge drinkers was significantly greater (Mean rank=240.5), than among lower level binge drinkers (Mean rank=105.9), U=288.0, p<0.001.

A-TLFB participants were asked about their drinking behavior in two ways – through anchoring the month with “special days” and through a question about special days for drinking. Ratios for both were calculated by dividing total number of drinks on nonspecial days/all nonspecial days; and total number of drinks on special days/all special days. Wilcoxon test results showed that the special drinking day ratio for those who reported at least one special day per month was significantly higher (Mean rank=21.3) than their nonspecial day drinking ratio (Mean rank=5.0), Z=4.6, p<0.001). Over a four week period, the graph shows that those with special drinking days drank consistently more average standard drinks per week than those with nonspecial days

Over a 30 day period, adherence days and nonadherence days were totaled for all 922 participants. The total number of adherence days for the sample across 30 days was 26372 and total nonadherence days were 1288. Mean nonadherent days per person was .04 days (1288/(1288+26372). Frequency of non-adherent days was the following:

Frequencies of unprotected sex in TLFB

Of 922 respondents, slightly less than half (422) had sex in the past 30 days. 387 participants had sex with wives, 20 had sex with regular partners, four had sex with other nonpaid partners and 11 had sex with paid partners. The total number of sexual encounter days for those who had sex was 1111, a mean of approximately 3 times per month. The total number of condom use days was 707; total number of condom nonuse days was 404 (36%).

Comparability of the A-TLFB and the Baseline Survey responses for drinking, adherence and unprotected sex

A comparison of 30 day drinking rates for different types of alcohol shows a high degree of comparability across measures, with the exception of strong beer which was reported slightly more often in the Baseline survey (TLFB = 229; survey=300). The association of alcohol consumption in the A-TLFB with the AUDIT had a medium effect size (rs=.59; p<0.001). The higher the number of standard drinks reported in the A-TLFB over the course of a month, the higher the AUDIT problem drinking score. The association between mean number of drinks on an average day in the A-TLFB and number of drinks on a typical drinking day in AUDIT-C was also significant (rs = .66, p <.001). The Kendall’s coefficient of concordance was high indicating low discordance between the two measures (Kendall’s W=.89, p<0.001).

The associations between four day adherence in TLFB and four day adherence in general survey were also significant (rs=.66, p<.001). The Kendall’s coefficient of concordance was high indicating low discordance of two measurements (Kendall’s W=.84, p<0.001) as was the correlation between 7 day nonadherence in the survey and the TLFB (rs =.63, p<.001). The Kendall’s coefficient of concordance between two measurements of 7 day adherence was high indicating low discordance of the two measurements (Kendall’s W=.89, p<0.001).

The association between total number of times of unprotected sex in TLFB versus total number of times of unprotected sex in general survey was significant (rs = .41, p<.001). The Kendall’s coefficient of concordance between the two measurements was low and not significant indicating a high level of discordance between the two measurements (Kendall’s W=.001, p=0.674).

Drinking Patterns and Risk Behavior

In this section we examine the pattern of co-occurrence of drinking behavior (overall and binge drinking), nonadherence and unprotected sex.

Drinking and same day adherence

The Wilcoxon rank test showed that on the days when PLHIV in the sample consumed any amount of alcohol, they were less likely to be adherent to their ART medication (Mean rank=101.7), Z=11.3, p<0.001). PLHIV who binged (Mean rank=43.6), were also less likely to adhere to medication the same day than participants who drank but did not binge (Mean rank =132.6), Z=11. 3, p<0.001.

Drinking and next-day adherence

Results of Wilcoxon rank test indicated that there was a significant difference in next-day adherence between participants who drank on the previous day and those who did not. Participants who drank (Mean rank=185.3) were less likely to adhere to medication the following day than participants who did not drink (Mean rank=350.8), Z=9.5, p<0.001.). However, in this case, binging on the previous day did not make a difference between participants who binged (Mean rank=103.3) and those who drank but did not binge (Mean rank =204.8), Z=0.3, p=0.797.).

Drinking and Same-Day Unprotected Sex

The Wilcoxon test results showed that PLHIV who had unprotected sex on a specific day were significantly more likely to have consumed alcohol on that day (Mean rank 81.7) than participants who did not consume alcohol (Mean rank =23.0), Z=7.6, p<0.001. Similar results are seen when comparing same day same-day unprotected sex and binge drinking. Participants who binged (Mean rank= 33.9) were significantly more likely to have risky sex on the same day than participants who drank but did not binge (Mean rank=11.2), Z=13.9, p<0.001)

Drinking and next-day unprotected sex

PLHIV who drank on the previous day (Mean rank= 98.25) were more likely to have unprotected sex the following day than participants who did not drink on the previous day (Mean rank=60.29), Z=6.2, p<0.001.) The same pattern is seen for binge drinkers in comparison to those who drank but did not binge. Participants who binged (Mean ranks= 35.13) were more likely to have risky sex on the following day than participants who did not binge on the previous day (Mean ranks=25.56), Z=3.8, p<0.001)

Differences in risk behaviors across three types of drinkers

Results of ANOVA test showed that there were significant differences in nonadherence across three different drinking patterns – binge drinking, and regular versus irregular drinking [(F (2, 907)=6.0; p<.001)]. A post-hoc Tukey HSD test showed that binge drinkers (p=0.032) and regular drinkers (p=.014), - those who drank more alcohol more often but did not binge, were significantly more likely to be non-adherent as compared to irregular drinkers. A Chi-square test results showed evidence indicating that binge drinkers differed from regular drinkers and irregular drinkers. Binge drinkers were more likely to engage in unprotected sex than both regular and irregular drinkers (X2 (2, 457) =18.5, p <.001).

Drinking threshold for nonadherence

The results of logistic regression (adjusting for age, education, marital status and employment) show that compared to participants who drank only 1 to 3 standard drink per month, those who had 4–9 standard drinks were likely to increase nonadherence by odds of 1.6 times (OR=1.6, 95% CI: 1.2–2.3, p<0.001) and those with 10 or more standard drinks were likely to increase nonadherence by odds of 2.3 times (OR=2.3, 95% CI: 1.6–3.1, p<0.001).

Recall pattern/recall bias

Researchers have raised questions about the accuracy of shorter or longer term recall periods for alcohol consumption, adherence and unprotected sex using TLFB or other recall approaches (59). To address this question the recall patterns of study participants examined over a 30 day period for alcohol consumption (number of drinks), nonadherence, and sexual risk taking (sex without condom with any partner

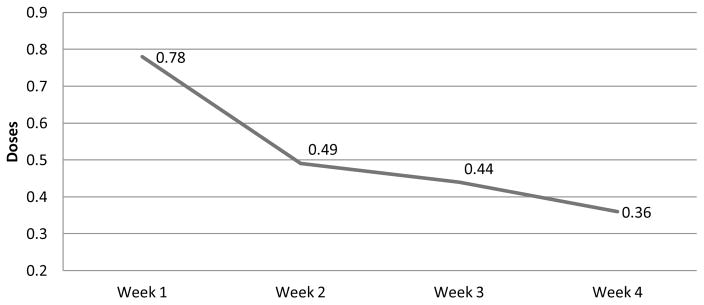

An examination of mean alcohol consumption (number of standard drinks) across all participants by week for four weeks showed that mean alcohol consumption declined over the four weeks, with the steepest decline from week 1 to week 2 but continuing through week four. To examine the pattern of nonadherence recall over the same 4 week period, the mean of nonadherence to ART medication per week was defined as the proportion of doses missed during 1-week period calculated each week for a four week period. The mean number of risky sex event per week was defined as the proportion of unprotected sex during a 1- week period calculated each week for a four week period.

The results in Figures II (earlier) and III for mean alcohol consumption and nonadherence show a statistically significant decay/decline in recalled events from Week 1 to Week 2, and a further slower decline thereafter. The pattern for sexual events over 28 days shows a statistically significant drop from week 1 to week 2 and a significant increase from week 3 to week four, showing variability in recall reflecting behavior over time (Figure 4).

Figure II.

Average standard drinks per week for nonspecial versus special drinking days

Figure III.

Mean of Nonadherence events by Week

Figure IV.

Mean of risky sex events per week (%)

Discussion

Evaluation of the Research Utility of the A-TLFB

Rehm and colleagues stressed the importance of considering patterns of alcohol use that goes beyond amount (usually measured by number of drinks over a specified period of time) to include temporal variations in drinking, occasional heavy or binge drinking, drinking locations and events, personal characteristics of drinking and types of beverages consumed (61). The AUDIT and other similar alcohol screeners addresses both quantity and pattern through questions related to drinking days, estimated number of drinks on an average drinking day and frequency of drinking a large number of drinks (usually 4 – 6) on each drinking occasion. However these measures, unlike the TLFB, do not allow for very specific calculations of drinking days, drinks per day, and sequences of drinking.

Though the measurement of alcohol consumption using the Timeline Followback procedure is widely used by researchers and clinicians in the West, there are relatively few examples of its use in India. The few papers conducting TLFB assessments use the approach (25, 27) to obtain more accurate counts of drinking days or drinking amounts in correlational studies, rather than exploring patterns of drinking and their daily or otherwise sequenced association with other behaviors. This study uses a version of the TLFB adapted specifically for Indian men on ART that collects data on the consumption of standard drinks of five different types of alcohol each day over a 30 day period, and integrates two additional measures of risk exposure related to HIV infection and diffusion, nonadherence and unprotected sex, creating the opportunity to gain a clearer understanding of how drinking behavior relates temporally with other forms of risk taking both on drinking days and days surrounding drinking days. It anchors the month with special events designed to assist in remembering periods in which drinking takes place (4–6). The adapted TLFB adds enhancements to improve recall including a laminated card that illustrates Indian terminology (Hindi, Marathi, the State language) for types of alcohol locally consumed and shows the measurement of a standard drink using typical size containers, four day, seven day and 3 week recall periods for the main variables (drinking, nonadherence and unprotected sex with different partners), and an additional probing question about “special days for drinking”.

Standard scales on the survey instrument allowed a comparison of results with the A-TLFB, The results showed a high degree of comparability suggesting that the A-TLFB can generate comparable results to the standard screeners and they are able to establish temporal patterns as well. The results in this paper also show good concordance between key A-TLFB and comparable survey measures on adherence. In contrast, the correlation with survey unprotected sex indicators was high but concordance was low.

In terms of recall, we have seen a pattern of decline in mean amount of alcohol consumed and proportion of nonadherence each week for four weeks, and a more variable pattern for unprotected sex. Those concerned about recall patterns have suggested that regular events are more likely to be recalled accurately in the past several weeks or month, while irregular events or those that occur infrequently are more likely to be recalled accurately over longer periods of time (67). This may well be the case with respect to sexual behavior since many male PLHIV in this sample have sex infrequently and may be able to estimate better over a three month period than to recall specifics over a one month period.

There is good concordance between the A-TLFB and the baseline survey in 30 day drinking days and binge drinking occasions, and between TLFB and survey questions on four and seven day recall. Seven day recall however, is not sufficient to measure amount or pattern of alcohol because it may change as a result of multiple contextual factors. A 14 day drinking recall period would capture short term recall accuracy plus an additional 7 days during which recall stabilizes but it might not capture low level binge drinking which could occur less frequently adherence data could also be collected for that period of time, with the expectation that it too would drop and stabilize after the second week. Though some have suggested that a 14 day period is sufficient to obtain general concordance between TLFB and other measures, we advocate a 30 day period for alcohol and adherence data, and, for unmarried or unstably married men, a 90 day period for unprotected sex prorated for 30 days.

Implications of A-TLFB results

This study has demonstrated a drinking prevalence rate of approximately 22% for PLHIV attending ART centers (37). This is less than the approximately 30% prevalence rate for drinkers reported across India (24) suggesting the possibility that many people quit or reduce drinking once they discover that they are HIV positive, though they may return to their pre-diagnosis patterns at a later date or vary their drinking behavior over time.

Benegal and others have discussed alcohol ambivalence as an Indian phenomenon, with the implication that the country is relatively new to exposure to many varieties of high alcohol content drinks and there are, as yet, few rules and norms governing alcohol consumption and more uncontrolled or hazardous drinking (62). The implication is that Indian drinkers especially men, are less able to control the number of drinks they drink at a sitting and that this uncontrolled pattern of drinking leads to a variety of health and behavioral problems. Hazardous drinking is defined in many different ways in India and elsewhere, making comparisons difficult. In this study, we have used the term binge drinking defined as 5 or more drinks in a single sitting, because this measure is standardized for India. Further ethnographic research with this population shows that drinking events take place in a short period of time after work or evenings, lasting approximately 2 hours, often without food. Consumption of five standard drinks (70 grams of pure alcohol) during that period of time can produce intoxication (63). Increases in binge drinking days are likely to be associated with corresponding increases in other risks (58). In addition to the obvious immediate effects of consuming a large amount of alcohol at a single sitting, there is evidence to suggest that more adverse events are associated with 2 or more days of binge (heavy) drinking a week than with more regular consumption of smaller amounts of alcohol (64).

The A-TLFB allows for an examination of these associations. Using the A-TLFB as a guide approximately, 62% of the sample is low level irregular drinkers and 70% have never drunk five or more drinks at a sitting. While alcohol consumption levels overall, as well as heavy (binge) drinking appear to be lower than in the general population of men in general (65) and in India (66), the evidence in the literature indicates that even low levels of drinking can be associated with health and behavioral risk. For example our results showed that those who had 4–9 standard drinks were 1.7 times more likely to be non-adherent (and those with 10 or more standard drinks were 2.3 times more likely to be non-adherent as compared to participants who drank only 1 to 3 standard drinks per month.

Thirty percent of our study sample drank 5 or more standard drinks at least once a month, and of these only a small percentage, referred to as higher level binge drinkers, did so five times a month or more. Many of these binge drinkers also drank on other days of the month as well although at lower levels. Overall, binge drinkers drank more pure alcohol than non-binge drinkers regardless of days of drinking per month, and higher level bingers consumed more pure alcohol per month than lower level bingers. We further differentiated those who binged at least once a month from those who drank four drinks or less a day regularly (more than four days a month) or irregularly (less than four days a month). Overall the amount of alcohol consumed was greatest for those who binged, less for those who drank regularly and still less for those who drank irregularly showing a direct association between pattern of drinking and amount of alcohol consumed.

Though most research shows a significant association between alcohol consumption, nonadherence and risky sex, the A-TLFB analysis has shown that on the days people drink, and on the day following a drinking day, people are much more likely to be non-adherent regardless of the amount that they drink, in other words, it is not binge drinking alone that produces nonadherence, it is regular alcohol use. In the case of unprotected sex however, binge drinking plays a more significant role with obvious implications for intervention.

Regarding recall bias, it could be anticipated that the most accurate recall is within the first week or two following an activity. For this reason, adherence researchers generally prefer four day recall, but alcohol researchers may vary the recall period from 14 to 30 days; and researchers concerned with irregular or more infrequent events such as unprotected sex with inconsistent partners or violent events prefer longer periods of time to enable capturing of these events (60). A flat line across a four week (30 day equivalent) period should be expected to represent accuracy of recall over that period of time. Variation across a four week period suggests either bias (a pattern of decrease or increase over time), or inconsistency in recall (short term repeated rises and falls).

Conclusion

The analysis of the data gathered by the A-TLFB used in this study has generated results that have important implications for those involved in both research and intervention with men who consume alcohol and are on ART medication in India and elsewhere. Despite a higher cost in time and training, the TLFB offers the best approach available for accurate retrospective recall of alcohol consumption and related risk behavior. With its capacity to address patterns of behavior and provide continuous rather than categorical estimates, the data provided can be used for multiple analytic purposes. At the same time the A-TLFB demonstrates good concurrence with standard scales (AUDIT and ACTG) including alcohol measures and nonadherence (especially in relation to the four day gold standard adherence recall questions) and risk behaviors obtained through survey questions and thus can replace these measures when duplication of measurement should be avoided. We have shown that 30 day recall is sufficient for both adherence and alcohol consumption but not for more irregular activities such as unprotected sex. We have also shown clearly that risk behavior occurs on the day of and the day after drinking and thus direct correspondence of drinking to risk behavior rather than the total amount drunk is what produces risk. These results could guide further exploration with respect to measuring neurotoxicity, beliefs about neurotoxicity, and its potential role in overall judgment regarding unprotected sex and nonadherence in PLHIV as well as seronegative drinkers.

To use the TLFB in HIV-related research we recommend modifying the administration procedure to include number of standard drinks for each alcohol type used in the setting, repeat of special drinking day probe, instructions for four day, seven day and 30 day recall to correspond to typical medication adherence recall questions used in epidemiologic surveys, a Likert scale for nonadherence (missed none, some or all prescribed medication), and unprotected sex days with all potential partners.

From an individualized tailored perspective, interventionists can utilize the A-TLFB by eliciting the daily information, and identifying sequencing and clustering patterns and encouraging modification of these patterns to reduce alcohol consumption. The drinking threshold analysis suggests that patients drinking over four standard drinks a month should consider reducing their monthly allocation and those who drink from nine or more three or fewer standard drinks a month could reduce their odds of nonadherence significantly. Further since more frequent binge drinking is associated with more negative health consequences including medication nonadherence, one approach to alcohol risk reduction is to work with binge drinkers to reduce their consumption to half the number of drinks per sitting, and to reduce the number of higher consumption days by half. From this perspective, the TLFB, adapted for each cultural group and identifying multiple risk behaviors can serve as an effect research and clinical tool.

Finally, the TLFB and its adaptations can be used in conjunction with other prospective measures designed to capture, examine the effects of and intervene in in-the-moment drinking. The TLFB can establish a typical antecedent pattern of drinking in combination with other risks, i.e. a “behavioral theory”, which can be validated with biomarkers. Patterns established through short term systematic retrospection and be tested and probed with ecological momentary assessments that offer the basis for in-situ (time and moment) interventions tailored to individual drinking behavior and context. These ideas remain to be explored in future research.

Table V.

Frequency of non-adherent days for the 30 day period

| Number of days | Number of participants | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 474 | 51.4 |

| 1 | 212 | 23.0 |

| 2 | 109 | 11.8 |

| 3 | 46 | 5.0 |

| 4 | 25 | 2.7 |

| 5 | 15 | 1.6 |

| 6 | 10 | 1.1 |

| 7 | 3 | .3 |

| 8 | 6 | .7 |

| 9 | 5 | .5 |

| 10 | 1 | .1 |

| 11 | 2 | .2 |

| 13 | 2 | .2 |

| 15 | 3 | .3 |

| 28 | 1 | .1 |

| 29 | 1 | .1 |

| 30 | 7 | .8 |

| Total | 922 | 100.0 |

Table VI.

Frequency of unprotected sex prorated over 30 day period

| Number of days | Participants | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 292 | 69.1 |

| 1 | 48 | 11.4 |

| 2 | 25 | 5.9 |

| 3 | 23 | 5.5 |

| 4 or more | 34 | 8.1 |

| Total | 422 | 100% |

Table VII.

| Table VIIa1. Mean number of drinks on average day: TLFB and AUDIT – C. (r=.436, p<.001, Kendall tau_b) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance (Kendall’s W) | p | |

| TLFB – mean number of drinks on an average day | 3.42 | 1.85 | Kendall’s W= 0.76 Indicating low level of discordance high level of concordance | 0.001 |

| AUDIT C – number of drinks at a time on a typical drinking day | 1.90 | 0.83 | ||

| Table VIIa2. Binge drinkers (6 or more) in TLFB and AUDIT-C measure of binge drinking (how often have you had six or more drinks at a sitting in AUDIT C (Sig.< .001) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance (Kendall’s W) | p | |

| TLFB – binge drinkers (6 or more binge) | 0.73 | 3.54 | Kendall’s W= 0.79 Indicating that low level of discordance and high level of concordance | 0.001 |

| AUDIT C – how often have you had six or more drinks at a sitting | 1.45 | 0.83 | ||

| Table VIIb. Correlation between 4 day and 7-day non-adherence in TLFB and 4 day and 7-day non-adherence in TLFB and survey general survey (Sig. <.001) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 day-non-adherence | ||||

| TLFB | 7.48 | 1.44 | Kendall’s W= 0.976 indicating high level of concordance | 0.001 |

| General survey | 0.92 | 0.26 | ||

| 7 day-non-adherence | 0.001 | |||

| TLFB | 13.22 | 2.16 | Kendall’s W= 0.896 indicating high level of concordance | |

| General survey | 0.66 | 2.20 | ||

| Table VIIc. Correlation between Unprotected Sex Ratio**: TLFB and Survey (Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLFB – total number of times of unprotected sex all partners, past 30 days* | 11.38 | 23.72 | Kendall’s W= 0.001 indicating highest level of discordance and low level of concordance | 0.674 |

| Survey – total number of times had sex unprotected all partners past 30 day* | 12.77 | 43.59 | ||

Risky sex was annualized (12 months) given discrepancies in timing of question on risky sex among wife regular partners and other partners

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study is provided through NIAAA grant # U01 AA021990-01

The authors express their appreciation to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIH for their support and funding for the study entitled Alcohol and ART Adherence: Assessment, Intervention and Modeling in India and to members of the India research team including PIs Avina Sarna, M.D., Niranjan Saggurti, Ph.D., and field team members Priti Prabhughate, DPH, Melita Vaz, DPH, Rajendra Singh, MA, Paras Verma, and to Manoj Pardeshi, Director, Maharashtra Network of Positive People and the team of facilitators guiding the group and community interventions. Finally the cooperation and feedback of the 940 participants in the study, have been critical to the quality of both the research and the intervention.

Appendix

Table VIII.

A-TLFB and Survey-related Indicators

| Variables | Structure | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| A-TLFB and Survey Alcohol-related indicators | ||

| Overall alcohol consumption | Number of standard drinks in total across 30 days | Self-reported total standard drinks over a 30 day period % average number of drinks consumed per drinking day/30 |

| Total ethanol consumption | Self-reported number of drinking days % number of standard drinks % total ethanol content per standard drink | |

| Binge drinkers | Drinking 5 or more drinks at a sitting at least once in 30 days | |

| Non-binge drinkers | Drinking less than five drinks on a given day regardless of their other drinking | |

| Days of binge drinking | Summing over 30 days to provide a 30-day total of number of binge drinking days per person | |

| Regular drinkers | Having no binge drinking days and engaging in more than 4 days of alcohol use in past 30 days | |

| Irregular drinkers | Having no binge drinking days and engaging in 4 or less days of alcohol use in the past 30 days | |

| A-TLFB and Survey Indicators of Non-adherence | Three self-reported adherence measures were used: 4 day and 7 day and 30 day questions | Full adherence (100% of prescribed 30 day doses: partial adherence (>/=95% and < 100% of prescribed 30 day-doses: and non-adherence (<95% of prescribed doses), creating two categories: full adherence (100% of prescribed 30 day doses) and non-adherence (<100% of prescribed doses) for each day and averaged across all 30 days to create a daily rate. In the Baseline survey, adherence was calculated as the percentage of doses taken over those prescribed over the past four days. Non-adherence was calculated as total number of doses missed/total number of doses prescribed in past 4 days |

| A-TLFB and Survey and Indicators of Unprotected Sex | Participants were asked for each of the 30 days whether they had sex and if a condom was used on each of these occasions | Participants were categorized as either having unprotected or protected sex on a given day for each of the past 30 days. An unprotected set ratio was determined by the total number of instances of unprotected sex over the total number of times sex occurred in the past 30 days |

References

- 1.Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112(3):178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braithwaite RS, Bryant KJ. Influence of Alcohol Consumption on Adherence to and Toxicity of Antiretroviral Therapy and Survival. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(3):280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goforth HW, Lupash DP, Brown ME, Tan J, Fernandez F. Role of Alcohol and Substances of Abuse in the Immunomodulation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease: A Review. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2004;3(4):174–182. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobell L, Sobell M. Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods: Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Totowa NJ: Humana Press; 1992. Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Measuring alcohol consumption. Springer; 1992. Timeline follow-back; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback user’s guide: A calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz L, Montero A, Gonzalez-Gross M, Vallejo A. Influence of alcohol consumption on immunological status: a review. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2002;56(S3):S50–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook RT, Stapleton JT, Ballas ZK, Klinzman D. Effect of a single ethanol exposure on HIV replication in human lymphocytes. Journal of investigative medicine: the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research. 1997;45(5):265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achappa B, Madi D, Bhaskaran U, Ramapuram J, Rao S, Mahalingam S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV. North American Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013;5(3):220–223. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.109196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2009;52(2):180–207. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuman MG, Schneider M, Nanau RM, Parry C. Alcohol consumption, progression of disease and other comorbidities, and responses to antiretroviral medication in people living with HIV. AIDS research and treatment. 2012;2012:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2012/751827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryant KJ, Nelson S, Braithwaite RS, Roach D. Integrating HIV/AIDS and alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(3):167–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amedee MA, Nichols AW, Robichaux S, Bagby JG, Nelson S. Chronic alcohol abuse and HIV disease progression: Studies with the non-human primate model. Current HIV research. 2014;12(4):243–253. doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140721115717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene B, Nevid J, Rathus S. Abnormal Behavior in Childhood and Adolescence. Pearson Education, Inc; Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: 2006. Abnormal Psychology in a Changing World; pp. 474–480. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kagee A, Delport T. Barriers to Adherence to Antiretroviral Treatment. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15(7):1001–1011. doi: 10.1177/1359105310378180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Tugenberg T. Social relationships, stigma and adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):904–910. doi: 10.1080/09540120500330554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vagenas P, Azar MM, Copenhaver MM, Springer SA, Molina PE, Altice FL. The Impact of Alcohol Use and Related Disorders on the HIV Continuum of Care: a Systematic Review. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2015;12(4):421–436. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0285-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, Freedberg KA, Palepu A. Alcohol consumption and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected persons with alcohol problems. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(4):572–577. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122103.74491.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. The Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Bass JK, Alexandre P, Mills EJ, Musisi S, Ram M, et al. Depression, alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(8):2101–2118. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, Swetsze C, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, et al. Alcohol and adherence to antiretroviral medications: interactive toxicity beliefs among people living with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2012;23(6):511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, McNerey M, White D, Kalichman MO, et al. Intentional nonadherence to medications among HIV positive alcohol drinkers: prospective study of interactive toxicity beliefs. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(3):399–405. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magidson JF, Li X, Mimiaga MJ, Moore AT, Srithanaviboonchai K, Friedman RK, et al. Antiretroviral medication adherence and amplified HIV transmission risk among sexually active HIV-infected individuals in three diverse international settings. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;20(4):699–709. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1142-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh SK, Schensul J, Gupta K, Maharana B, Kremelberg D, Berg M. Determinants of alcohol use, risky sexual behavior and sexual health problems among men in low income communities of Mumbai, India. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):48–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9732-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saggurti N, Raj A, Mahapatra B, Cheng DM, Coleman S, Bridden C, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Non-Disclosure of HIV Serostatus to Sex partners among HIV-Infected Female Sex Workers and HIV-infected Male Clients of Female Sex Workers in India. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(1):399–406. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0263-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verma RK, Saggurti N, Singh AK, Swain SN. Alcohol and sexual risk behavior among migrant female sex workers and male workers in districts with high in-migration from four high HIV prevalence states in India. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):31–39. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9731-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samet JH, Pace CA, Cheng DM, Coleman S, Bridden C, Pardesi M, et al. Alcohol Use and Sex Risk Behaviors Among HIV-Infected Female Sex Workers (FSWs) and HIV-Infected Male Clients of FSWs in India. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):74–83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9723-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheward DJ, Ntale R, Garrett NJ, Woodman ZL, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C. HIV-1 superinfection resembles primary infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2015;212(6):904–908. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.UNAIDS I. The gap report. Geneve: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.NACO. National AIDS Control Organization PART B. Delhi, India: Ministry of Family Health and Welfare; 2014–2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yadav D, Chakrapani V, Goswami P, Ramanathan S, Ramakrishnan L, George B, et al. Association between alcohol use and HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men (MSM): findings from a multi-site bio-behavioral survey in India. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(7):1330–1338. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0699-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schensul JJ, Singh S, Gupta K, Bryant K, Verma R. Alcohol and HIV in India: a review of current research and intervention. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9740-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prasad R. Alcohol use on the rise in India. The Lancet. 2009;373(9657):17–18. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61939-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuckler D, McKee M, Ebrahim S, Basu S. Policy Forum Manufacturing Epidemics: The Role of Global Producers in Increased Consumption of Unhealthy Commodities Including Processed Foods, Alcohol, and Tobacco. PLoS. 2012;9(6):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001235. Epub e1001235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das SK, Balakrishnan V, Vasudevan D. Alcohol: its health and social impact in India. National Medical Journal of India. 2006;19(2):94–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mimiaga M, Thomas B, Mayer K, Reisner S, Menon S, Swaminathan S, et al. Alcohol use and HIV sexual risk among MSM in Chennai, India. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2011;22(3):121–125. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schensul S, Ha T, Schensul J, Vaz M, Singh R. The Role of Alcohol on ART Adherence among Persons Living with HIV in Urban India. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017 doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.716. (accepted for publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dawson DA, Room R. Towards agreement on ways to measure and report drinking patterns and alcohol-related problems in adult general population surveys: the Skarpö Conference overview. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Letourneau B, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Agrawal S, Gioia CJ. Two Brief Measures of Alcohol Use Produce Different Results: AUDIT-C and Quick Drinking Screen. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41(5):1035–1043. doi: 10.1111/acer.13364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubinsky AD, Dawson DA, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. AUDIT-C Scores as a Scaled Marker of Mean Daily Drinking, Alcohol Use Disorder Severity, and Probability of Alcohol Dependence in a US General Population Sample of Drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(8):1380–1390. doi: 10.1111/acer.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frank D, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Effectiveness of the AUDIT-C as a Screening Test for Alcohol Misuse in Three Race/Ethnic Groups. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(6):781–787. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0594-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson JA, Lee A, Vinson D, Seale JP. Use of AUDIT-Based Measures to Identify Unhealthy Alcohol Use and Alcohol Dependence in Primary Care: A Validation Study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;(37):E253–E259. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T. A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21(4):613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGinnis KA, Justice AC, Kraemer KL, Saitz R, Bryant KJ, Fiellin DA. Comparing Alcohol Screening Measures Among HIV-Infected and Uninfected Men. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(3):435–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerr WC, Stockwell T. Understanding standard drinks and drinking guidelines. Drug and alcohol review. 2012;31(2):200–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenfield TK, Nayak MB, Bond J, Patel V, Trocki K, Pillai A. Validating Alcohol Use Measures Among Male Drinkers in Goa: Implications for Research on Alcohol, Sexual Risk, and HIV in India. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):84–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9734-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nayak MB, Kerr W, Greenfield TK, Pillai A. Not all drinks are created equal: implications for alcohol assessment in India. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2008;43(6):713–718. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metrik J, Caswell AJ, Magill M, Monti PM, Kahler CW. Sexual Risk Behavior and Heavy Drinking Among Weekly Marijuana Users. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77(1):104–112. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, Carey KB. Alcohol and Risky Sexual Behavior Among Heavy Drinking College Students. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(4):845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Room R, Mäkelä P, Benegal V, Greenfield TK, Hettige S, Tumwesigye NM, et al. Times to drink: cross-cultural variations in drinking in the rhythm of the week. International Journal of Public Health. 2012;57(1):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dulin PL, Alvarado CE, Fitterling JM, Gonzalez VM. Comparisons of alcohol consumption by timeline followback vs.smartphone-based daily interviews. Addiction Research & Theory. 2017;25(3):195–200. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2016.1239081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hjorthøj CR, Hjorthøj AR, Nordentoft M. Validity of Timeline Follow-Back for self-reported use of cannabis and other illicit substances — Systematic review and meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simpson CA, Xie L, Blum ER, Tucker JA. Agreement between prospective interactive voice response telephone reporting and structured recall reports of risk behaviors in rural substance users living with HIV/AIDS. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(1):185–190. doi: 10.1037/a0022725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wray TB, Braciszewski JM, Zywiak WH, Stout RL. Examining the reliability of alcohol/drug use and HIV-risk behaviors using Timeline Follow-Back in a pilot sample. Journal of Substance Use. 2016;21(3):294–297. doi: 10.3109/14659891.2015.1018974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stein MD, Anderson BJ, Caviness CM, Rosengard C, Kiene S, Friedmann P, et al. Relationship of Alcohol Use and Sexual Risk Taking Among Hazardously Drinking Incarcerated Women: An Event-Level Analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(4):508–515. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schick VR, Baldwin A, Bay-Cheng LY, Dodge B, Van Der Pol B, Fortenberry JD. “First, I… then, we…”: exploring the sequence of sexual acts and safety strategies reported during a sexual encounter using a modified timeline followback method. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2016;92(4):272–275. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG Adherence Instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Santos G-M, Jin H, Raymond HF. Pervasive Heavy Alcohol Use and Correlates of Increasing Levels of Binge Drinking among Men Who Have Sex with Men, San Francisco, 2011. Journal of Urban Health. 2015;92(4):687–700. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9958-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fiellin DA, Mcginnis KA, Maisto SA, Justice AC, Bryant K. Measuring alcohol consumption using Timeline Followback in non-treatment-seeking medical clinic patients with and without HIV infection: 7-, 14-, or 30-day recall. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(3):500–504. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Johnson ME. HIV Risk Behavior Self-Report Reliability at Different Recall Periods. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):152–161. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rehm J, Ashley MJ, Room R, Single E, Bondy S, Ferrence R, et al. On the emerging paradigm of drinking patterns and their social and health consequences. Addiction. 1996;91(11):1615–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benegal V, Chand PK, Obot IS. Packages of care for alcohol use disorders in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fillmore MT, Jude R. Defining “Binge” Drinking as Five Drinks per Occasion or Drinking to a 0. 08% BAC: Which is More Sensitive to Risk? The American journal on addictions/American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions. 2011;20(5):468–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reich RR, Cummings JR, Greenbaum PE, Moltisanti AJ, Goldman MS. The temporal “pulse” of drinking: Tracking 5 years of binge drinking in emerging adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124(3):635–47. doi: 10.1037/abn0000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ikeda MLR, Barcellos NT, Alencastro PR, Wolff FH, Moreira LB, Gus M, et al. Alcohol drinking pattern: a comparison between HIV-infected patients and individuals from the general population. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0158535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thirumagal V, Velayutham K, Panda S. A study of alcohol use pattern among married men in rural Tamil Nadu, India-policy implications. International Journal of Prevention and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders. 2015;1(3–4) [Google Scholar]

- 67.Janssen T, Braciszewski JM, Vose-O’neal A, Stout RL. A Comparison of Long-vs. Short-Term Recall of Substance Use and HIV Risk Behaviors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78(3):463–467. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]