Abstract

Deaths due to acute coronary insufficiency have been reported during or following electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Various mechanisms related to ECT related deaths also include cerebral, and respiratory complications; however, cardiovascular complication remains the most common. Here, we describe a 55 year old male with a longstanding psychiatric illness with multiple antipsychotics under regular follow-up and required repeated ECT therapy to have the disease symptoms under remission. This time he developed acute onset chest pain immediately post ECT shock and diagnosed as Acute anterior wall myocardial infarction and was taken up for successful primary coronary revascularization to left anterior descending (LAD) artery 2 h after the chest pain onset. He was later discharged in a stable state and advised for continuous psychiatric follow-up.

Keywords: Coronary revascularization, Electroconvulsive therapy, Schizophrenia

1. Introduction

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a safe and effective treatment for severe mood disorders. Rarely there can be serious complications, such as postictal agitation, cardiovascular compromise, prolonged seizures, and status epilepticus, all of which are important for the clinician to recognize and treat.1 Cardiac complications are the principal cause of medical complications related to ECT.2 Although they are usually insignificant, a small percentage of these cardiac complications can be potentially fatal. The variety of cardiac complications of ECT may be grouped in terms of cardiac ischemia, heart failure, and arrhythmic complications. Here we report a case of acute anterior wall myocardial infarction immediately following ECT which was successfully managed with primary revascularization.

2. Case report

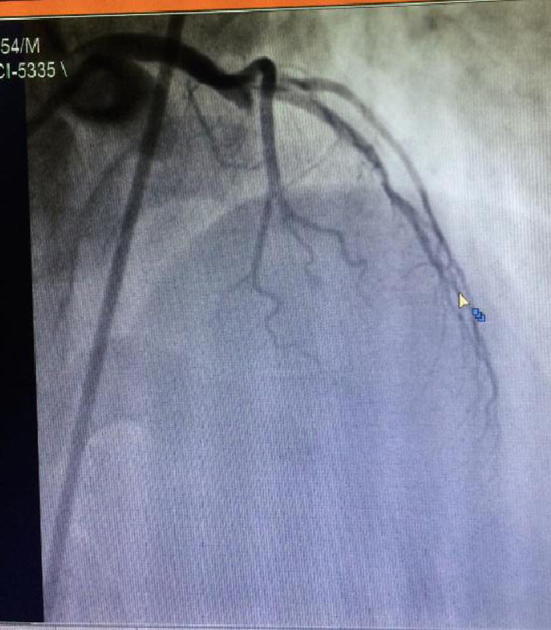

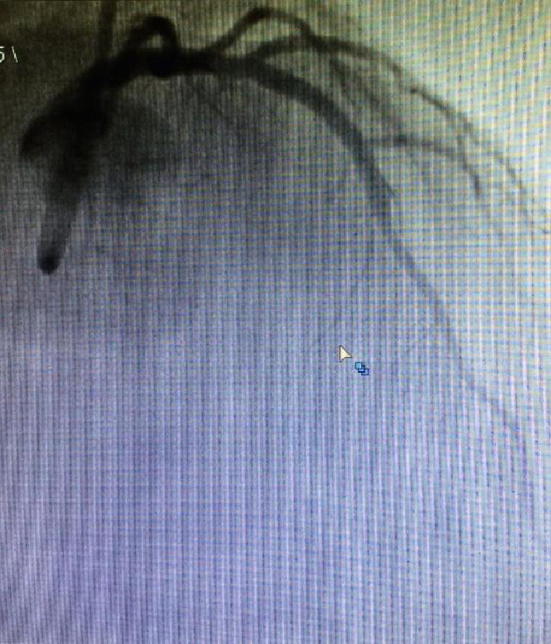

54 year old male diabetic and a known case of Paranoid Schizophrenia on regular psychiatric follow-up was referred as a case of acute coronary syndrome to our centre. He also had a history of multiple repeated ECT therapy prior to presentation for the same refractory psychiatric symptoms. Immediate to the recent post-ECT, he developed acute onset retrosternal chest discomfort, radiating to both the arms, severe intensity associated with diaphoresis. On examination, BP was 110/80 mmHg, PR – 90/min, Spo2 97% and clinically afebrile. Other systemic and cardiovascular examinations were within normal limits. ECG at presentation revealed ST elevation in V2 to V6 leads with CPK MB was 237 U/L and Trop I being positive. Other laboratory parameters included normal renal function test and total leukocyte counts. Lipid profile revealed total cholesterol 250 mg/dl, HDL cholesterol 35 mg/dl, and LDL cholesterol 166 mg/dl. He was taken up for primary PCI which revealed a proximal LAD lesion with TIMI 0 flow. Balloon dilation followed by stent deployment was done with 3 × 28 mm drug eluting stent into the LAD was done, after which successful TIMI 3 flow was maintained (Figure 1, Figure 2). Later, he was chest pain free and was discharged on dual anti[platelets], statin, ACEI, and beta blockers and asked to regular cardiology and psychiatric follow-up.

Figure 1.

Angiogram showing LAD lesion cutoff.

Figure 2.

Post PCI to LAD lesion.

3. Discussion

Cardiac complications following ECT may range from arrhythmic to acute coronary syndromes associated with high morbidity and mortality. Ischemic complications reported include both ST segment and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.3 Arrhythmic complications are by far the most common. They include minor transient arrhythmias, such as premature ventricular contractions, but also significant tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias, such as atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, new left and right BBBs, 2nd degree AV block, junctional bradycardia, and asystolic cardiac arrest.4, 5

The arrhythmic complications of ECT can be easily understood through the concept of seizure-induced autonomic nervous system activity. During the early phase of the seizure, parasympathetic activity predominates with a fall in pulse rate and blood pressure. This is followed by a sympathetically induced rise in pulse rate and blood pressure. These physiological responses can precipitate a variety of cardiac complications especially in patients with preexisting heart disease.5 Symptomatic myocardial ischemia is rare after ECT, and there is insufficient evidence to support pharmacologic therapy for the prevention of post-ECT myocardial ischemia. Our patient had a long history of type 2 Diabetes mellitus, as well as long duration of different typical antipsychotics including clozapine and trifluoperazine which in addition have an adverse effect on the lipid profile which predisposes to more accelerated atherogenesis. The acute hemodynamic and autonomic stress associated with ECT may precipitate an acute coronary syndrome on the background of diseased atherosclerotic coronaries. There are substantial variations in hemodynamic sequelae; Takada and colleagues reported a 25% increase in mean arterial pressure and a 52% increase in heart rate.6 Preexisting cardiac disease has been associated with increased complication rates, although most complications remain minor and the vast majority of patients can safely complete treatment.7

There are no specific guidelines for the stratification of cardiac risk before ECT. However, ECT is analogous to a low-risk procedure as defined in 2007 in the clinical guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC–AHA) for the perioperative care of patients undergoing non cardiac surgery.8 Our index case developed acute coronary syndrome immediately following the ECT therapy after which the standard primary revascularization was done and patient was discharged after few days in a hemodynamically stable state.

4. Conclusion

Acute myocardial infarction is a rare complication noted post electroconvulsive therapy. In patients with no active cardiac conditions (e.g. decompensated congestive heart failure, unstable angina, significant arrhythmias, and valvular disease) noninvasive cardiac testing is unnecessary, and practitioners can proceed with risk-factor modification as appropriate. However, those with active cardiac conditions need proper pre operative, non invasive or invasive cardiac evaluation and necessary management prior to ECT therapy. Our case had no prior cardiac illness nor had any active cardiac condition, though developed an acute coronary syndrome related to ECT treatment.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Egyptian Society of Cardiology.

Contributor Information

Anish Hirachan, Email: hirachananish@gmail.com.

Arun Maskey, Email: maskeyarun@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Cristancho M.A., Alici Y., Augoustides J.G., O’Reardon J.P. Uncommon but serious complications associated with electroconvulsive therapy: recognition and management for the clinician. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(6):474–480. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice E.H., Sombrotto L.B., Markowitz J.C., Leon A.C. Cardiovascular morbidity in high-risk patients during ECT. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1637–1641. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuttall G.A., Bowersox M.R., Douglass S.B. Morbidity and mortality in the use of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2004;20(4):237–241. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200412000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerring J.P., Shields H.M. The identification and management of patients with a high risk for cardiac arrhythmias during modified ECT. J Clin Psychiatry. 1982;43(4):140–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zielinski R.J., Roose S.P., Devanand D.P., Woodring S., Sackeim H.A. Cardiovascular complications of ECT in depressed patients with cardiac disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1637–1641. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takada J.Y., Solimene M.C., da Luz P.L. Assessment of the cardiovascular effects of electroconvulsive therapy in individuals older than 50 years. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005;38:13495. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005000900009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zielinski R.J., Roose S.P., Devanand D.P., Woodring S., Sackeim H.A. Cardiovascular complications of ECT in depressed patients with cardiac disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:9049. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleisher L.A., Beckman J.A., Brown K.A. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1707–1732. [Google Scholar]