Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s Distress Thermometer (DT) has been adopted as a screening measure to identify and address psychological distress in individuals with cancer. The purpose of the present study was to establish an optimal cut off point in a large heterogeneous sample of cancer patients. A secondary purpose of the study was to examine whether distress as measured by the DT significantly changes across the treatment trajectory (i.e., diagnosis, on treatment, survivorship).

Design

The present investigation includes secondary analyses of baseline data from a longitudinal parent study examining a computerized psychosocial assessment.

Setting

Recruitment occurred at three diverse comprehensive cancer centers across the United States.

Sample

Eight hundred and thirty-six patients at 3 different comprehensive cancer centers with a current or past diagnosis of cancer were enrolled.

Main Research Variables

The BHS (Behavioral Health Status) index, as well as the DT were administered and compared using ROC analyses.

Findings

Results support a cutoff score of 3 on the DT to indicate patients with clinically elevated levels of distress. Further, patients who received a diagnosis within the 1-4 weeks prior to the assessment endorsed the highest levels of distress.

Conclusions

Providers may wish to utilize a cutoff point of 3 to most efficiently identify distress in a large, diverse population of cancer patients. Further, results indicate that patients may experience a heightened state of distress within the 1-4 weeks post-diagnosis as compared to other stages of coping with cancer.

Implications for Nursing

It is widely understood that nurses carry a heavy burden regarding patient care. It is often a nurse’s responsibility to screen for psychosocial distress, and using a brief technological measure of distress can help streamline this process.

Keywords: NCCN DISTRESS THERMOMETER, ONCOLOGY, CUT OFF, PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS

Introduction

Specific consequences of psychological distress in cancer care can include: greater difficulty in decision making, seeking more health services, substandard adherence to treatment and doctor recommendations, poor satisfaction with medical care, and decreased quality of life (Holland, 1997). Despite estimates that 24% to 50% of patients with cancer exhibit symptoms of distress, and can experience the aforementioned effects, psychological symptoms are not consistently addressed by all care teams (Carlson et al., 2004; Holland & Bultz, 2007; Jacobson & Ransom, 2007; Mitchell, Vahabzadeh, & Magruder, 2011; Psychosocial Distress Practice Guidelines Panel, 1999; Roth et al., 1998; van Scheppingen et al., 2011). Even in those patients exhibiting high levels of distress, rates of referral and access to psychosocial services tend to be low (Carlson, Waller, & Mitchell, 2012; Ellis et al., 2008; Verdonck-de Leeuw et al., 2009; Zebrack et al., 2015). Whether because of a lack of education regarding the utility of psychosocial support or a stigma regarding mental health care, highly distressed patients may not even express interest in, utilize, or follow up with a variety of psychosocial services (Roth et al, 1998; Tuinman, Gazendam-Donofrio, & Hoekstra-Weebers, 2008; Waller et al., 2011). This discrepancy between high distress and low engagement in therapeutic interventions is problematic and warrants future investigation.

Brief screening instruments have been developed to serve as economical and efficient ways to identify potential psychosocial difficulties. Early diagnosis and treatment of distress has the potential to reduce emotional suffering, as well as the severity of physical symptoms and excessive utility of health services (Carlson & Bultz, 2004; Carlson, Groff, Maciejewski, & Bultz, 2010; Faller et al., 2013; Holland, 1997; Holland & Bultz, 2007; Jacobson & Ransom, 2007; Mehnert & Koch, 2007; Roth et al., 1998). Brief screening measures can also improve patient-provider communication and can promote psychosocial referrals (Carlson et al., 2012). Although there are clear potential benefits to screening patients for distress and subsequent psychosocial intervention, only a small number of cancer centers implement such methods across all patient care. Jacobsen and Ransom surveyed 15 of the 18 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) member institutions and determined that only 20% reported screening all patients for psychological distress, as guidelines recommend (Jacobson & Ransom, 2007). Because of time constraints or treatment demands, oncology providers may avoid using screening or clinical interview measures and instead rely on clinical judgment, which is not always accurate when it comes to identifying distress (Mitchell, Hussain, Grainger, & Symonds, 2011; Werner, Stenner, & Schuz, 2012).

In 1997, the NCCN created distress management guidelines, which consist of a 1-item global screener of distress (the Distress Thermometer), an accompanying problem list, and treatment recommendations for psychosocial issues (Psychosocial Distress Practice Guidelines Panel, 1999). The NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT) is a one-item, 11-point Likert scale represented on a visual graphic of a thermometer that ranges from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress), with which patients indicate their level of distress over the course of the week prior to assessment. Patients who report high levels of distress can be administered the accompanying 40-item problem list (PL), detailing common problems related to the cancer experience. This PL helps providers identify whether the patient is experiencing practical, family, emotional, spiritual-religious, or physical problems. The goal is that asking for distress ratings will become as common as asking for pain ratings, and that distress will become the “Sixth Vital Sign” in cancer care (Holland & Bultz, 2007). The DT has proven to be feasible, accessible, and informative (Jacobson & Ransom, 2007; Mitchell, 2010). Studies have tested the validity of the DT, most of which have compared it to the widely accepted Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Chambers, Zajdlewicz, Youlden, Holland, & Dunn, 2014; Grassi et al., 2013; Holland & Bultz, 2007; Mitchell, 2010; Thalén-Lindström, Larsson, Hellbom, Glimelius, & Johansson, 2013; Jacobsen et al., 2005, etc.). The findings of Akizuki et al. (1997) also support the DT as an effective method of identifying psychological distress in cancer populations. Based on the results of diagnostic interviews with psychiatrists, the authors found that patients with clinical diagnoses scored significantly higher on the DT than those without a diagnosis.

Originally, a cut off score of 5 was used to identify those patients experiencing significant distress, because of its numerical placement as midpoint of the 11-point scale (Psychosocial Distress Practice Guidelines Panel, 1999; Roth et al., 1998). However, the most recent version of the NCCN practice guidelines for the management of distress recommends that a DT score of 4 or higher indicates moderate-to-severe distress (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2013). In research involving mixed samples, cut-off scores indicating distress vary by culture, language, setting, and demographics, but most studies support a DT cut-off score of 4 or 5 (Donovan, Grassi, McGinty, & Jacobsen, 2014; Jacobsen et al., 2005; Grassi et al., 2013; Mansourabadi, Moogooei, & Nozari, 2014; Martinez, Galdon, Andreu, & Ibanez, 2013). When researchers have attempted to establish cut offs for disease specific groups, these findings have demonstrated a range of results. For example, using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses, research has validated the use of the DT in many cancer populations. A cut off of 6 or higher has been established for intracranial tumors, 5 for breast cancer patients, and 4 for brain cancer patients (Dabrowski et al., 2007; Goebel & Medhorn, 2011; Iskandarsyah et al., 2013; Keir, Calhoun-Eagan, Swartz, Saleh, & Friedman 2008). Optimal DT cut-off scores may also vary over time. In a sample of prostate cancer patients, DT cut-off score to identify significant distress decreased from 4 soon after diagnosis to 3 at longer-term assessments (Chambers et al., 2014). Although these disease specific findings may be the best option for providers working in one specialized area of oncology, for many community cancer centers where the majority of cancer patients (85%) are diagnosed and treated, providers need a tool and validated cut off score to use with heterogeneous groups of cancer patients (National Cancer Institute, 2007). Because of these discrepant findings, further research is needed.

The purpose of the present investigation was to establish a comprehensive DT cut off score based on a large heterogeneous sample of cancer patients and to determine whether this cut off was affected by the time lapse since diagnosis. DT scores were compared to Behavioral Health Status (BHS) index scores, which were used to indicate low, moderate, and high levels of distress based on patient reports of psychological symptoms (anxiety, depression), functional disability, and subjective well-being (Grissom, Lyons, & Lutz, 2002).

Method

Participants

A Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT) was conducted to determine the efficacy of a computerized psychosocial assessment for cancer care, the Mental Health Assessment and Dynamic Referral for Oncology (MHADRO) (Boudreaux et al., 2011). The MHADRO assessment was administered to a heterogeneous sample of 836 patients at three diverse comprehensive cancer centers: The University of Massachusetts Medical School Cancer Center (n=581; 70%), the Cancer Institute of New Jersey at Cooper Hospital (n=126; 15%), and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (n=129; 15%). Eligibility criteria included a current or past diagnosis of cancer, being over the age of 18, and a lack of significant cognitive deficits that may impact ability to fully consent to study. Enrolled participants were more likely than those who declined enrollment to be female (86% vs. 78%, χ2(1)=21.99, p=.000), younger (x=58.9 (s.d.=11.7) vs. 62.6 (s.d.=13.1), F(1,2235)=45.74, p = .000), and White/Caucasian (92% vs. 86%, compared to Black/African American and to all other races combined, χ2(2)=29.09, p=.000). Type of cancer also varied significantly for enrolled compared to non-enrolled patients (n = 1,424), with a higher percentage of enrolled participants having breast cancer (49% vs. 37%, χ2(1)=31.43, p=.000).

Procedure

Data for the present paper were collected through an NIH-funded Phase II randomized control trial exploring the psychosocial effects of cancer and cancer treatment. The Mental Health Assessment and Dynamic Referral for Oncology (MHADRO) is a patient-completed computerized psychosocial assessment designed to identify and address physical, psychological, and social issues faced by oncology patients (Boudreaux et al., 2011). The MHADRO required participants to complete a baseline assessment during a chemotherapy or routine oncology appointment on a touch-screen tablet. Patients were recruited at all points during the cancer trajectory (i.e., diagnosis, on treatment, survivorship). Patients were approached for enrollment during a chemotherapy infusion or an ambulatory care appointment with an oncologist. Oncologists helped a research assistant to identify eligible participants. Each patient was given information about the study’s purpose and participant requirements. They were informed that participation would not delay their care, and that they could withdraw from the study or terminate the assessment at any time. Individuals with nausea or pain which precluded enrollment were re-approached during later appointments. Once a participant signed the informed consent, the research staff entered the individuals’ identifying information into the MHADRO system to begin the assessment. The participant was randomly assigned to one of two study conditions. Participants in the intervention group received three printed reports including details of their psychological adjustment: one was provided to the patient, one was shared with their oncologist, and one was placed in the electronic medical record. Participants in the intervention group who scored high in distress automatically received the contact information for two appropriate mental health providers based on their zip code and insurance carrier as a part of their printed report. In addition, these participants were given the option to choose to automatically send a dynamic referral for an appointment with one of these providers at the completion of the MHADRO assessment. Participants in the control group completed the same MHADRO assessment, and then received standard care for psychosocial issues. Participants were recruited, enrolled into the study, and then were randomized to the intervention or control group before completing the assessment. The consent form signed by all participants was explicit in that patients would be enrolled and then randomized to either intervention or control condition. Randomization into the intervention or control group was completed by an internal random number generator programmed into the software. The research assistant was blind to study assignment until the patient completed the assessment, whereupon it was necessary to determine the participant’s group assignment to carry out the rest of the protocol (i.e., disseminating the patient reports). Follow-up assessments will be completed at 2, 6, and 12 months from baseline. The University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board approved all procedures. The present investigation utilizes baseline data from the parent RCT. All of the longitudinal data will be used for future publications. The full methodology has been recently published (O’Hea et al., 2013).

Measures

Behavioral Health Status (BHS)

The Behavioral Health Status (BHS) scale is a global measure of mental health, based upon Phase and Dose-Response models of psychotherapy outcome (Howard, Kopta, Krause, & Orlinsky, 1986; Howard, Lueger, Maling, & Martinovich, 1993). The BHS is a 45-item composite of three subscales: Subjective Well-Being, Psychological Symptoms and Functioning; the three dimensions of the Phase model. The Psychological symptoms subscale is further broken down into symptoms of anxiety and depression. The BHS was validated using a large sample (N = 600) of outpatient mental health patients. Each of the subscales was validated against one or more established scales (e.g., SCL-90-R, General Well-Being Scale, Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Social Adjustment Scale) and have good internal consistency reliability (Grissom et al., 2002). The internal consistency (coefficient alpha) for the BHS subscales were all high enough to treat each scale as a single construct (Subjective Well-Being, α = .82; Psychological Symptoms, α = .90; Functioning, α = .84). The composite BHS has good reliability (.88) and concurrent validity (r =.87, p < .001 vs OQ45), and good sensitivity to change (effect size =.60; p <.001). It was chosen as the foundation of the MHADRO assessment because the goal was to identify patients who would find most benefit from mental health services in conjunction with cancer treatment. The BHS has been used clinically with college students, substance abuse outpatients, and cardiovascular disease patients. One goal of the parent MHADRO study is to validate the BHS in oncology populations.

Using the BHS (Grissom et al., 2002), the core of the MHADRO assessment evaluated patients in three general areas: psychological symptoms (depression and anxiety), physical functioning, and subjective well-being. Patients were appraised based on their ability to function emotionally as well as physically, given the distress they experience on a daily basis. This BHS scale combined the scores of three subscales: psychological symptoms, functioning, and subjective well-being (Grissom et al., 2002). The BHS score placed participants into one of three categories: those with low, moderate, or high distress. The cutoffs for low, moderate, and high distress were based on percentile scores comparing each patient to a normative database that consisted of other MHADRO patients at intake. This normative database began with Phase 1 data and was updated many times as more MHADRO data were collected (Boudreaux et al., 2011). Because this normative data was gathered from a cancer patient population, it may represent this population of interest more closely than would normative data gathered from a general population. Higher scores signify more severe symptoms and worse functioning. Patients with scores in the 70th percentile or above were considered clinically elevated in distress, patients who fell below the 30th percentile were considered low in distress, and others in between the 30th and 70th percentiles were considered within normal limits.

Psychological Symptoms

Depression

The 5-item depression subscale assessed patients on their symptoms of sadness, loss of pleasure from previously enjoyable activities, feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, pessimism, and difficulty concentrating. Each item presented a 4-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating better (less severe) outcomes.

Anxiety

The 5-item anxiety subscale evaluated symptoms of worry, feeling tense or “keyed up”, irritability and anger, and, again, difficulty concentrating. Each item presented a 4-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating better outcomes.

Functional Disability

The functional disability subscale converts 5 items to a 5-point Likert scale. The average of these scores represents participants’ activity level and the amount that physical and emotional symptoms impinge on daily life management. Scores are coded so that higher scores indicate better functioning.

Subjective Well-Being

This 1-item measurement required participants to indicate how well they had been getting along psychologically and emotionally on a 5-point scale. The responses range from 1 (quite poorly, can barely manage to deal with things) to 5 (quite well, no important complaints).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT)

Participants rated their distress level using the DT (Psychosocial Distress Practice Guidelines Panel, 1999). As described above, the DT has been validated using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses in numerous oncology populations and has held up against other validated and lengthier measures.

Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. To characterize the association between DT scores and categorical characteristics of interest we used analysis of variance. When significance was achieved we further examined specific group differences by calculating least squares means. The least squares means approach is preferred because it both allows for adjustment for multiple comparison testing as well as unbalanced designs. Specifically, we used a Tukey-Kramer adjustment (Kramer, 1956) that accommodates unequal sample sizes in groups.

We assessed the association between NCCN scores and the BHS through calculating a Spearman Correlation. We conservatively chose to calculate a Spearman correlation rather than a Pearson correlation because the former only requires the data to be measured at least at the ordinal scale (rather than the interval scale requirement of Pearson correlation) and makes no assumptions about the underlying distribution.

Using a similar approach to that described above, we further investigated the relationship between the NCCN and the BHS using analysis of variance. Based on the categorization of low, moderate, and high distress as measured by the BHS and described earlier in the Methods, we determined if there was a difference in the NCCN score based on group membership. When significance was achieved we further examined specific group differences by calculating least square means.

We used ROC curves and the associated c-index to investigate the relationship between psychological distress as measured by the NCCN and BHS scores. Specifically, we were interested in determining if a cut-point with acceptable sensitivity and specificity could be defined on the NCCN that corresponded to higher distress on the more thoroughly examined and commonly used BHS score. As a reference, a BHS score in the highest tertile (percentile score greater than or equal to 70%) was considered highly distressed. Several logistic regression models predicting the probability of high distress (as measured by the BHS score) with varying cut-points on the NCCN score were developed and the corresponding sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values were calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A description of sample characteristics is presented in Table 1. A history of 11 mental health diagnoses were endorsed (e.g., depression, bipolar, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, anxiety, panic attacks, PTSD, ADD/ADHD, anorexia, bulimia, schizophrenia), though the most common were depression (24%) and anxiety (14%). Thirty-five patients (4%) had been hospitalized due to an emotional problem at least once in their lifetime. Thirty one percent of the total sample had been prescribed psychotropic medication, 20% of which were taking medication at time of enrollment. Thirty seven percent of patients had seen a counselor or therapist to help manage emotions or stress and 8% were in therapy at the time of assessment. When asked whether they would benefit from counseling at the time of enrollment, 17% of participants in the intervention group (n=415) said “yes” and 18% indicated that they were “not sure.”

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample: The MHADRO Study (N=836)

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity: N (%) | ||

| White/Non-Hispanic | 723 (90.7) | |

| Black/Non-Hispanic | 39 (4.9) | |

| Hispanic | 35 (4.4) | |

| Sex: N (%) | ||

| Male | 118 (14.1) | |

| Female | 718 (85.9) | |

| Marital Status: N (%) | ||

| No | 294 (35.2) | |

| Yes | 542 (64.8) | |

| Education: N (%) | ||

| College Graduate or Above | 342 (40.9) | |

| Less than College Graduate | 494 (59.1) | |

| Cancer Type: N (%) | ||

| Breast | 410 (49.2) | |

| Lung | 44 (5.3) | |

| Colon/Rectal | 45 (5.4) | |

| Gynecologic | 178 (21.3) | |

| Prostate/Testicular | 12 (1.4) | |

| Other | 145 (17.4) | |

| Time Since Diagnosis: N (%) | ||

| Today/Within the past week | 27 (3.2) | |

| 1-4 weeks ago | 41 (4.9) | |

| 1-6 months ago | 216 (25.8) | |

| More than 6 months ago | 552 (66) | |

| Age: Mean (SD) | 59.35 (11.6) |

Relationship between BHS and DT

To examine the relationship between DT scores and BHS index scores, a Spearman correlation coefficient and associated p value were calculated and the two variables were found to be significantly related (rho = 0.58, p < 0.0001). As distress measured by the BHS index increased, the mean DT scores increased. Further, least squares means analyses revealed that each category of BHS score was related to a significantly different DT score. For all three categories (low distress, within normal limits, clinically elevated distress), mean DT scores (m = 0.79, 2.58, 4.78 respectively) differed at the p < 0.0001 level.

Cut-off Point Analyses

Cutoff points were determined using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Analysis. ROC curve and the associated c-index were used to investigate the relationship between psychological distress as measured by the NCCN and BHS scores. Specifically, we were interested in determining if a cut-point with acceptable sensitivity and specificity could be defined on the NCCN that corresponded to higher distress on the BHS score. As a reference, a BHS score in the highest tertile (percentile score greater than or equal to 70%) was considered highly distressed. Several logistic regression models predicting the probability of high distress (as measured by the BHS score) with varying cut-points on the NCCN score were developed and the corresponding sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values were calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC).

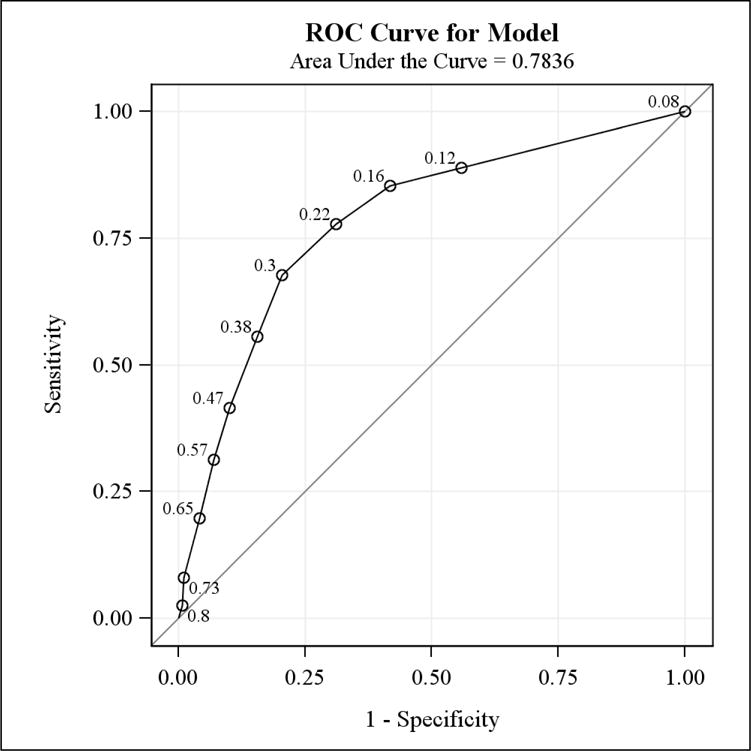

The predictive accuracy of the NCCN score in predicting high distress as measured by the BHS was 0.784 (c-statistic; Figure 1). Based on the cut-point for distress using the NCCN score, sensitivity ranged from 0.31 to 0.78 and specificity from 0.69 to 0.93 (Figure 1). The current recommended cut-point on the NCCN scale, 4, had a sensitivity of 0.68 and a specificity of 0.79. The corresponding positive and negative predictive values were 0.51 and 0.89 respectively. A cut-point of 3 on the NCCN scale was found to have higher sensitivity (0.78) and a higher negative predictive value (0.91) but lower specificity (0.69) and a lower positive predictive value (0.44).

Figure 1.

ROC Curve from Model predicting High Distress using the BHS Score from the NCCN Score: The MHADRO Study

* Labeled points on the ROC curve correspond to the average high distress score (measured on a 0-1 scale from the BHS) at each value of the NCCN thermometer. For example, at a thermometer score of 3 (read from the top right corner), the average high distress score 0.22.

NCCN Scores and Time Since Diagnosis

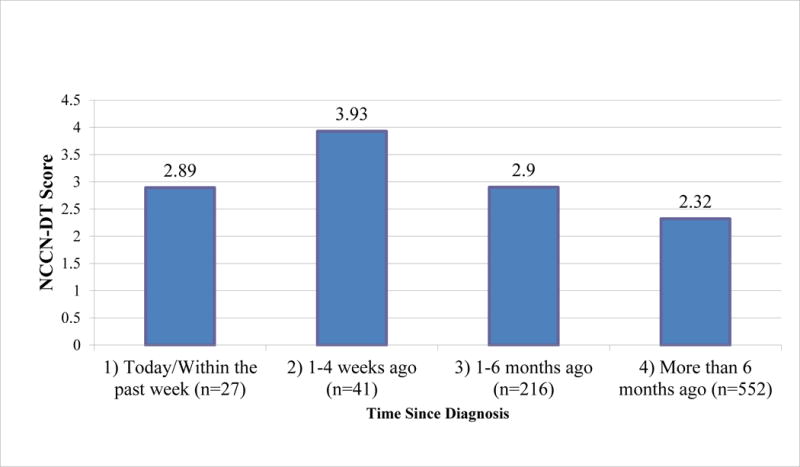

A statistically significant difference in distress was found among patients, depending on the amount of time that had lapsed since the diagnosis of cancer. Figure 2 demonstrates mean levels of distress at each of the four times since diagnosis. The following categories are significantly different from each other, at the p < .05 level: 1-4 weeks vs. 1-6 months; 1-4 weeks vs. more than 6 months; and 1-6 months vs. more than 6 months.

Figure 2.

Mean DT Scores at each time since diagnosis (N = 836)

Discussion

Oncology providers and governing bodies in oncology care agree that the psychosocial needs of individuals with cancer should be identified and addressed. Efficient and accurate screening tools are helpful to providers who are attempting to accomplish these goals. The present study examined the DT as a brief screening tool for distress and was compared to a psychometrically validated assessment of distress. In accordance with previous research, scores on the brief DT were significantly associated with scores on the lengthier BHS index (Chambers et al., 2014; Donovan et al., 2014; Goebel & Mehdorn, 2011). Also, time since diagnosis was related to scores on the DT. Specifically, patients who were in the period of time 1-4 weeks after receiving the diagnosis endorsed more distress than patients at any other time in the cancer trajectory, even those patients who were in the first week post-cancer diagnosis. This poses an immediate need to ensure that patients receive the option for psychosocial services when they are diagnosed with cancer as this may help them navigate the difficult journey on which they are about to embark. Figure 2 illustrates distress levels among patients who received their diagnoses at varying intervals of time. The findings in Figure 2 are consistent with previous research that has demonstrated the fluctuation of distress levels over the course of coping with cancer, which may be due to the uncertainty surrounding cancer treatment (Chambers et al., 2014; Lam, Shing, Bonanno, Mancini, & Fielding, 2012; Nosarti, Roberts, Crayford, McKenzie, & David, 2002; Wang, Tu, Liu, Yeh, & Hsu, 2013; Ziegler et al., 2011). During the first week, patients may be feeling numb or in a state of derealization before they have fully processed the diagnosis (National Cancer Institute, 2013). Once the diagnosis has sunk in, but before treatment plans have been determined, patients may experience heightened distress, which could explain the high levels of distress during that 1-4 week post-diagnosis interval. This time between diagnosis and beginning of treatment could be described as the ‘in limbo’ time, when patients are anxious because they have not begun actively fighting the cancer through treatment. Providers may need to screen for distress symptoms in patients during this phase, and it may be helpful to offer mental health services as well. These proactive measures may serve to help patients transition through the different phases of coping with cancer.

This study may have implications for the clinical use of brief screeners of psychosocial distress in cancer populations. Our analyses indicated that using a cutoff of 3 to indicate high levels of distress may maximize sensitivity and be a more useful option in some heterogeneous clinical settings. Because this score is lower than the one recommended by the NCCN Guidelines, it raises the issue of over-diagnosing distress in a clinical setting, using valuable provider time and resources. Indeed, another option would be to use multiple cutoff points depending on the situation. For example, in situations where distress may not be as prevalent (e.g., after the 1-4 week window post diagnosis), providers may consider erring on the side of caution and using a lower cutoff score. Future research should examine different DT cutoffs at different points in the treatment trajectory in a heterogeneous sample.

The current study had limitations that could be addressed through future research. First, the use of the BHS index does not necessarily predict clinical diagnoses. Optimally, each participant in the study would have undergone clinical psychological evaluation, in addition to administration of the DT, in order to more accurately predict clinical outcomes. Another major limitation was the demographic characteristics of the sample. Though enrollment did not exclude any cancer type or stage of disease, almost half of the sample consisted of female breast cancer patients and cancer survivors comprised over half of the sample. This may have occurred because those who enrolled in a study examining the effectiveness of a psychosocial intervention are those that would be most interested in utilizing such intervention. Women with cancer do tend to report greater levels of psychological distress as compared to men with cancer (Akin, Can, Avdiner, Ozdilli, & Durna, 2010; Thomas, NandaMohan, Niar, & Pandey, 2011). While distress levels did not vary among cancer types, previous research suggests that certain types of cancer, specifically brain cancer, might result in higher distress levels (Keir, Calhoun-Eagan, Swartz, Saleh, & Friedman, 2008). Also, race and ethnicity of the sample was largely white and non-Hispanic, again causing generalizability of results to be questionable. Future researchers are encouraged to replicate the present study with more diverse samples regarding disease type, gender, and ethnicity.

The NCCN Distress Guidelines are vague as far as how often it is recommended that patients be screened for distress. Perhaps using a cutoff score of 3 at first will help providers to identify patients who are distressed, and from there make a plan moving forward. The DT can be used once psychosocial resources are established, to ensure that distress has decreased. Further, a DT score of 3 could perhaps alert a nurse to conduct further assessment to determine in which domain the concern lies (e.g., practical, emotional, spiritual, physical). Also, it will be helpful to note that individuals who are female, older, less educated, and carry a higher symptom burden, are more likely to endorse symptoms of distress (Waller et al., 2013). It may be the case that these patients who are at higher psychosocial risk should be assessed more frequently and thoroughly.

As noted above, a majority of participants in our sample were cancer survivors. It is hypothesized that these patients, who were no longer in treatment, may have been feeling physically better and less acutely anxious or distressed. Previous research has demonstrated that as time since diagnosis increases, patients tend to experience an improved physical and mental status. At the same rate, there are many social and emotional challenges survivors face when coming off of treatment (Jarrett et al., 2013). There is a movement in many cancer care centers to build ‘survivorship clinics’. Future research with the DT is needed to establish cut off points for screening survivors who are experiencing a whole new set of stressors as they enter into formal survivorship.

Knowledge Translation.

A DT score of 3 may be the optimal cut off score to help providers identify high levels of distress in adult cancer patients

DT scores differ significantly from each other at different time points on the cancer treatment trajectory.

A total of 35% of participants endorsed “yes” or “maybe” when asked if they would like an immediate referral sent to a mental health provider.

Implications for nursing.

In a comprehensive cancer center, nurses are often responsible for psychosocial screening of patients, whether using a validated screening measure or clinical judgment (Werner et al., 2012). In the current literature, it is becoming more important to screen cancer patients and provide resources for distress throughout the treatment trajectory, even when preparing to come off treatment. Nurses are becoming more involved with a growing practice of survivorship care planning, that is, helping cancer survivors to prepare to transition back to primary care after completion of cancer treatment, a process which can be emotionally difficult for survivors who have grown accustomed to the social support of the oncology team (Lester, Wessels, & Jung, 2014). These additional demands of assessing and providing resources to patients are being placed on nurses, who are already an overworked and systematically underappreciated population. However, even brief screening measures of distress have been supported as efficacious. It is important to come up with ways to administer measures of distress while minimizing the burden on nurses. This may be done through brief screeners such as the DT and the use of technology programs, like the MHADRO, to complete more in-depth psychosocial assessments when needed. Regardless of the assessment tools chosen by oncology care providers, it is clear that the future of managing psychosocial issues in medical patients will need to involve efficient, technological options that can minimize burden on nurses and maximum benefits to patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This grant was funded by the NIH/NIMH (grant no. R42 MH078732).

Declaration of conflicting interests: This grant was funded through a Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) mechanism from the NIH/NIMH. Intellectual property, licensing and revenue income from the Mental Health Assessment and Dynamic Referral for Oncology (MHADRO) program are shared between Polaris Health Directions and the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Dr. Boudreaux and Dr. O’Hea also consult for Polaris Health Directions. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding:

This study was funded through a Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) mechanism from the NIH/NIMH. Intellectual property, licensing and revenue income from the Mental Health Assessment and Dynamic Referral for Oncology (MHADRO) program are shared between Polaris Health Directions and the University Medical School. Dr. Boudreaux and Dr. O’Hea also consult for Polaris Health Directions.

Footnotes

Pre-trial registration number: NCT01442285

References

- Akin S, Can G, Avdiner A, OZdilli K, Durna Z. Quality of life, symptom experience, and distress of lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010;14:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akizuki N, Akechi T, Nakanishi T, Yoshikawa E, Okamura M, Nakano T, Uchitomi Y. Development of a brief screening interview for adjustment disorders and major depression in patients with cancer. Cancer. 1997;97:2605–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux ED, O’Hea EL, Grissom G, Lord S, Houseman J, Grana G. Initial development of the Mental Health Assessment and Dynamic Referral for Oncology (MHADRO) Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2011;29(1):83–102. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2010.532299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, Goodey E, Koopmans J, Lamont L…Bultz BD. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;90(12):2297–2304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Bultz BD. Efficacy and medical cost offset of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: Making the case for economic analyses. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:837–849. doi: 10.1002/pon.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Groff SL, Maciejewski O, Bultz BD. Screening for distress in lung and breast cancer outpatients: A Randomized Control Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 28:4884–4891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1160–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers SK, Zajdlewicz L, Youlden DR, Holland JC, Dunn J. The validity of the distress thermometer in prostate cancer populations. Psycho-Oncology. 2014;23:195–203. doi: 10.1002/pon.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski M, Boucher K, Ward JH, Lovell MM, Sandre A, Bloch J…Buys SS. Clinical experience with the NCCN distress thermometer in breast cancer patients. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2007;5(1):104–11. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan KA, Grassi L, McGinty HL, Jacobsen PB. Validation of the Distress Thermometer worldwide: State of the science. Psycho-Oncology. 2014;23:241–250. doi: 10.1002/pon.3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J, Lin J, Walsh A, Lo C, Shepherd FA, Moore M, Rodin G. Predictors of referral for specialized psychosocial oncology care in patients with metastatic cancer: The contributions of age, distress, and marital status. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;27:699–705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Kuffner R. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:782–793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.8922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel S, Mehdorn HM. Measurement of psychological distress in patients with intracranial tumours: the NCCN distress thermometer. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2011;104(1):357–64. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi L, Johansen C, Annunziata MA, Capovilla E, Costantini A, Gritti P, Bellani M. Screening for distress in cancer patients: a multicenter, nationwide study in Italy. Cancer. 2013;119:1714–1721. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissom GR, Lyons JS, Lutz W. Standing on the shoulders of a giant: Development of an outcome management system based on the dose model and phase model of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research. 2002;12(4):397–412. doi: 10.1093/ptr/12.4.397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J. Preliminary guidelines for the treatment of distress. Oncology. 1997;11(11):109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC, Bultz BD. The NCCN guideline for distress management: A case for making distress the sixth vital sign. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2007;5(1):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard KI, Kopta SM, Krause MS, Orlinsky DE. The dose-effect relationship in psychotherapy. The American Psychologist. 1986;4:159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard K, Lueger R, Maling M, Martinovich Z. A phase model of psychotherapy: Causal mediation of outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:678–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, Soemitro MP, Sadarjoen SS, Passchier J. The Distress Thermometer and its validity: A first psychometric study in Indonesian women with breast cancer. PLOS One. 2013;8:e56353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056353. Retrieved from http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0056353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F, Holland JC. Screening for psychological distress in ambulatory cancer patients: A multicenter evaluation of the Distress Thermometer. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494–502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson PB, Ransom S. Implementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutions. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2007;5(1):99–103. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett N, Scott I, Addington-Hall J, Amir Z, Brearley S, Hodges L, Foster C. Informing future research priorities into the psychological and social problems faced by cancer survivors: A rapid review and synthesis of the literature. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2013;17:510–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keir ST, Calhoun-Eagan RD, Swartz JJ, Saleh OA, Friedman HS. Screening for distress in patients with brain cancer using the NCCN’s rapid screening measure. PsychoOncology. 2008;17:621–25. doi: 10.1002/pon.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer CY. Extension of multiple range tests to group means with unequal numbers of replications. Biometrics. 1956;12:307–310. doi: 10.2307/3001469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam WWT, Shing YT, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, Fielding R. Distress trajectories at the first year diagnosis of breast cancer in relation to 6 years survivorship. PsychoOncology. 2012;21:90–99. doi: 10.1002/pon.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester JL, Wessels AL, Jung Y. Oncology nurses’ knowledge of survivorship care planning: The need for education. Oncology Nursing Forum. 41:E35–E43. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.E35-E43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansourabadi A, Moogooei M, Nozari S. Evaluation of distress and stress in cancer patients in AMIR Oncology Hospital in Shiraz. Iranian Journal of Pediatric Hematology Oncology. 2014;4:131–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez P, Galdon MJ, Andreu Y, Ibanez E. The Distress Thermometer in Spanish cancer patients: Convergent validity and diagnostic accuracy. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21:3095–3102. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehnert A, Koch U. Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental disorders in breast cancer patients during primary cancer care: A prospective study. Psycho-Oncology. 16:181–188. doi: 10.1002/pon.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A. Short screening tools for cancer-related distress: A review and diagnostic validity meta-analysis. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2010;8:487–94. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Hussain N, Grainger L, Symonds P. Identification of patient-reported distress by clinical nurse specialists in routine oncology practice: A multicenter UK study. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:1076–1083. doi: 10.1002/pon.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Vahabzadeh A, Magruder K. Screening for distress and depression in cancer settings: 10 lessons from 40 years of primary-care research. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:572–584. doi: 10.1002/pon.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Distress management Version1. 2013 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Adjustment to cancer: Anxiety and distress. National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/adjustment/Patient/page2. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. NCI Community Cancer Centers Program Pilot: 2007–2010 [Fact sheet] 2007 Retrieved October 20, 2012, from http://ncccp.cancer.gov/Media/FactSheet.htm Oncology Nursing Forum.

- Nosarti C, Roberts JV, Crayford T, McKenzie K, David AS. Early psychological adjustment in breast cancer patients: A prospective study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hea EL, Cutillo A, Dietzen L, Harralson T, Grissom G, Person S, Boudreaux ED. Randomized control trial to test a computerized psychosocial cancer assessment and referral program: Methods and research design. Contemporary Clinical Trial. 2013;35(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial Distress Practice Guidelines Panel. NCCN Practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress. Oncology. 1999;13:113–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, Peabody E, Scher HI, Holland JC. Rapid screening for psychological distress in men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 1998;82:1904–08. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söllner W, DeVries A, Steixner E, Lukas P, Sprinzl G, Rumpold G, Maislinger S. How successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived social support, and need for psychosocial counseling? British Journal of Cancer. 2001;84:179–85. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thalén-Lindström A, Larsson G, Hellbom M, Glimelius B. Validation of the Distress Thermometer in a Swedish population of oncology patients; Accuracy of changes during six months. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2013;17:625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BC, NandaMohan V, Nair MK, Pandey M. Gender, age, and surgery as a treatment modality leads to higher distress in patients with cancer. Supportive Cancer Care. 2010;19:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0810-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask PC, Paterson A, Riba M, Brines B, Griffith K, Parker P, Ferrara J. Assessment of psychological distress in prospective bone marrow transplant patients. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2002;29:917–925. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice. Cancer. 2008;15:870–878. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, de Bree R, Keizer AL, Houffelaar T, Cuijpers P, van der Linden MH, Leemans CR. Computerized prospective screening for high levels of emotional distress in head and neck cancer patients and referral rate to psychosocial care. Oral Oncology. 2009;45:e129–e133. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodermaier A, Linden W, Siu C. Screening for emotional distress in cancer patients: A systematic review of assessment instruments. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;10:1464–88. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Scheppingen C, Schroevers MJ, Smink A, van der Linden YM, Mul VE, Langendijk JA, Sanderman R. Does screening for distress efficiently uncover meetable unmet needs in cancer patients? Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:655–663. doi: 10.1002/pon.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller A, Williams A, Groff SL, Bultz BD, Carlson LE. Screening for distress, the sixth vital sign: Examining self-referral in people with cancer over a one-year period. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:388–395. doi: 10.1002/pon.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WT, Tu PC, Liu TJ, Yeh DC, Hsu WY. Mental adjustment at different phases in breast cancer trajectory: Re-examination of factor structure of the Mini-MAC and its correlation with distress. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:768–774. doi: 10.1002/pon.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A, Stenner C, Schuz J. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting: How accurate is the detection of distress in the oncologic after-care? Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21:818–826. doi: 10.1002/pon.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B, Kayser K, Sundstrom L, Savas SA, Henrickson C, Acquati C, Tamas RL. Psychosocial distress screening implementation in cancer care: An analysis of adherence, responsiveness, and acceptability. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:1165–1171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler L, Hill K, Neilly L, Bennett MI, Higginson IJ, Murray SA, Stark D. Identifying psychological distress at key stages of the cancer illness trajectory: A systematic review of validated self-report measures. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;41:619–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]