Abstract

The inherent heterogeneity in cell populations has become of great interest and importance as analytical techniques have improved over the past decades. With the advent of personalized medicine, understanding the impact of this heterogeneity has become an important challenge for the research community. Many different microfluidic approaches with varying levels of throughput and resolution exist to study single cell activity. In this review, we take a wide view of the recent microfluidic developments for single cell analysis based on microwell, microchamber, and droplet platforms. We cover physical, chemical, and molecular biology approaches for cellular and molecular analysis including newly emerging genome-wide analysis.

Graphical Abstract

We present a review on recent advances on single cell analysis based on microfluidic platforms.

1. Introduction

Microfluidic technologies are able to easily improve sensitivity, reduce cost, and minimize operator influence in the operation of biological assays, and therefore have become widely applied to a number of different fields. Microfluidics has the advantage of working with picoliter to nanoliter volumes of solution that help to reduce sample loss and cost of reagents. Additionally, they are highly automatable with the ability to be multiplexed to create high-throughput assays. These features of microfluidics make it an ideal platform to analyze the heterogeneity of single cells.1, 2

Microfluidics takes different forms and shapes. There are two primary forms of microfluidics: channel microfluidics and droplet microfluidics. Channel microfluidic systems utilize microscale channels and chambers that allow for all flow to be in the laminar regime. The laminar flow allows for highly reproducible and well understood flow patterns within the microfluidic structures. These devices are typically manufactured using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), etched glass, or silicon which is then bonded to glass. Many channel microfluidic technologies make use of multi-layer soft lithography, which allows the use of a channel for sample flows and a layer that consists of valves to manipulate the sample flow through the use of an applied pressure. 3, 4 In contrast, droplet microfluidics utilizes the immiscibility of water and oil to create pico- and nanoliter scale droplet microreactors.5, 6 The ease and speed of generation combined with simple encapsulation of single cells by using a dilute suspension makes it the ideal high-throughput technology for single cell analysis.7, 8 Individual droplets can be transported, merged, mixed, and divided using on-chip processes. 5 Additionally, the generation of unique barcodes in single droplets makes pooling samples for data analysis much simpler.9–12 Digital microfluidics (DMF) is a subset of droplet microfluidics, also known as electrowetting on dielectric (EWOD), which is a different technological approach to developing lab-on-chip systems.13, 14 EWOD systems are made up of separate surfaces that are able to change hydrophobicity when applied with an electric field. An array of these surfaces allow for the movement and manipulation of droplets of solution.

Single cell analysis has been gaining attention and popularity in recent years. There is a known heterogeneity to exist within a population of seemingly identical cells.15, 16 This is particularly important when primary cell samples from lab animals and patients are concerned. For this reason, it is important to study individual cells to understand the complex biology of the heterogeneous population. These minute differences in cellular activities could be essential in the development of personalized medicine and disease research. The ability to analyze a population of cells to isolate drug resistant cells for further analysis is one of the most important applications for developing effective therapeutic methods. 17

The methods for single cell analysis are broad and include everything from measuring physical properties of cells, to protein analysis, deciphering cell signaling, and DNA/RNA sequencing. Using these examinations it is possible to make previously unknown breakthroughs by looking at rare tumor cells such as circulating tumor cells 18, 19. It can additionally be used to study cancer stem cells in order to understand the disease progression and make more effective chemotherapeutics 20, 21.

Earlier developments for single cell analysis began primarily with cytometric analysis of single cells, rapidly screening fluorescent labeled cells in a flow 22, 23. As the field has evolved, microfluidics allowed for a much wider range of analysis that would not be economical or feasible using a traditional platform. For example, further developments in single cell proteomic analysis were brought through the controlled breakage of single cells and further analysis of their contents. 24, 25

This review of microfluidic single cell analysis will cover recent developments ranging from single cell sample collection to various examination methods (physical, chemical, molecular/nucleic acid analyses). These works were conducted on various platforms that enabled high throughput (flow cytometry, microarray, microwells, and droplets).

2. Single cell manipulation and isolation

The first step in any sort of single cell analysis is collecting single cell samples for examination. Conventional and commonly-used single cell isolation methods include serial dilution, fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS), and Laser capture microdissection (LCM). Serial dilution and micro-pipetting rely on manual micro-manipulation of single cells with the advantages of being cheap and easy to perform while the disadvantages of being labor-consuming and low throughput. They have been used to isolate cells for single cell culture26 and genomic analysis.27, 28 Commercial FACS is an automatic single cell sorting and analysis system with high throughput and accuracy, which could sort or isolate single cells into tubes or microwells for downstream applications.29, 30 LCM is another commercial system, which employs laser to precisely cut and isolate specific single cells from tissues through direct microscopic visualization. 31

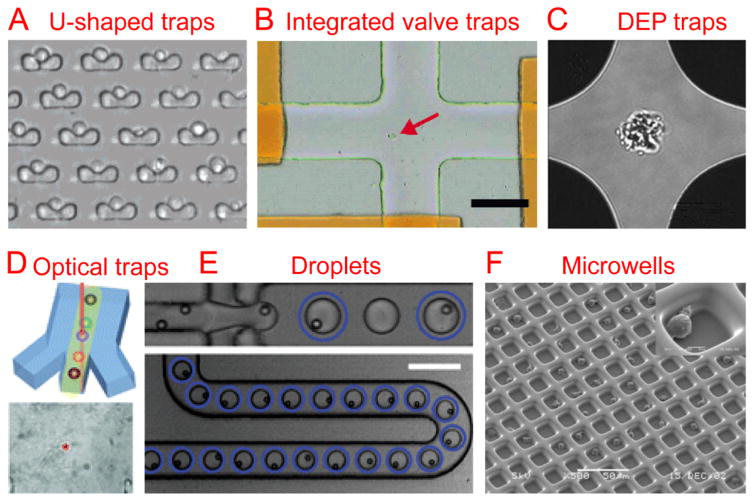

Currently, various microfluidic systems have been developed for single cell isolation and analysis based on a variety of basic micro-manipulation techniques, including hydrodynamic cell traps, valve traps, electrical traps, optical traps, droplets, and microwells. Other techniques for single cell sorting exist, such as acoustic32–35 and magnetic sorting.36–39 These microfluidic methods provide a number of inherent advantages over the conventional methods previously mentioned, such as downstream integration, automation, cost reduction, and a reduced risk of sample contamination.

2.1. Hydrodynamic Cell Traps

The most common method of collecting single cells for analysis is by using a hydrodynamic trap. A hydrodynamic cell trap is simply a system where the cell is removed from the flow of a cell suspension after being stopped by microscale structures (such as U-shaped structure) or hydrodynamic tweezers for examination. Hydrodynamic tweezers usually require specific and complex fluid flow profiles to trap single cells or particles40, 41 and have been reviewed previously42.

U-shaped traps

These cell traps consist of one or more positive U-shaped structures within a flow cell that capture single cells from a bulk solution. One of the earliest single cell U-shaped traps was demonstrated by Di Carlo et al. for isolating about 100 individual HeLa cells to observe their growth and adherence within 24 h (Fig. 1A).43 This type of U-shaped structure has also been utilized to perform fluorescent analysis of intracellular calcium of a single cardiac myocyte44 and study single cell enzyme kinetics for HeLa, 293T, and Jurkat cells.45 U-shaped traps have been further modified by adding small drainage channels in the capture structure which would allow the fluid to flow through before trapping a cell. 46,47 Compared to the unmodified U-shaped traps, it was reported that this improvement helps reduce the amount of stress placed on the cell, to enable the analysis of more fragile cells.46 In order to reduce the number of empty structures without compromising on loading time, Chung et al. 48 and Yesilkoy et al. 49 designed a hydrodynamic trap array that split the flow cell into individual channels, and by utilizing channel focusing with small capture structures with drainage channels, was able to quickly trap single cells using only gravity driven flow, ultimately achieving ~70% trapping efficiency and >90% fill factors. Recently, Zhang et al. integrated U-shaped traps into a hand-held single cell pipet (hSCP) device for rapid and highly-efficient isolation of single cells from cell suspensions into well plates, Petri dishes, or tubes for further analysis.50

Fig. 1.

Microfluidics-based single-cell isolation methods. (A) U-shaped traps. Reprinted with permission from D. D. Carlo, et al., Anal. Chem., 2006, 78, 4925–4930. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society. (B) Integrated valve traps. Reprinted with permission from J. W. Hong, et al., Nat. Biotechnol., 2004, 22, 435–439. Copyright 2004 Macmillan Publishers Ltd. (C) DEP traps. Reprinted with permission from U. C. Schroder, et al., Anal. Chem., 2013, 85, 10717–10724. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. (D) Optical traps. Reprinted with permission from A. Y. Lau, et al., Lab Chip, 2008, 8, 1116–1120. Copyright 2008 The Royal Society of Chemistry. (E) Droplets. Reprinted with permission from J. F. Edd, et al., Lab Chip, 2008, 8, 1262–1264. Copyright 2008 The Royal Society of Chemistry. (F) Microwells. Reprinted with permission from A. Revzin, et al., Lab Chip, 2005, 5, 30–37. Copyright 2005 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Bypass-channel traps

While the drainage channels are parallel to the main flow channel in U-shaped traps, bypass-channel traps usually consist of bypass channels with drainage channels perpendicular to the main flow channel. This allows them to not only trap single cells at the bypass channels, but to also perform physical manipulation of the cell once it enters the capture structure. Yamaguchi et al. demonstrates a microfluidic system consisting of a parallel capture channel and buffer channel to capture multiple single cells for analysis and culture. 51 The system used a micro-pocketed main channel with drainage channels in each micro-pocket connected to the buffer channel. The system was able to capture and release cells based on the difference between flow rates of the capture and buffer channels. Similar structures have been developed to enable high-efficiency single cell trapping.52–54 Chung et al. further optimized the geometry structures of the traps and the hydrodynamic resistances of the channels, achieving the trapping of 4,000 single cells in 4.5 mm2 within 30 seconds as well as with high efficiency (>95%). 55 Hong et al. integrated this cell trap into a microfluidic cell co-culture platform in which each trapping unit could sequentially capture two different cells via changing fluidic resistance. Using this platform, the interaction between mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) at the single cell level has been demonstrated.56

2.2. Integrated valve traps

Trap structures can come from the top or bottom of microchannels, such as traps supplied by integrated valves (i.e. Quake valves). Hong et al. integrated parallel valves into a microfluidic chip to achieve the steps from cell isolation to purified DNA recovery, in which single cells were trapped at the closed intersection of two microchannels (Fig. 1B).57 Ottesen et al. further developed a microfluidic digital PCR chip integrated with 1176 parallel chambers, and these chambers could be individually isolated by closing valves to trap single cells for performing independent PCR.58 These integrated valve traps can also be used to achieve on-chip multiple processing from single cell isolation to single cell lysis. It can also include different kinds of single cell analyses, such as Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA),59–61 digital PCR (dPCR),62 whole-transcriptome analysis,63 and protein analysis.64

2.3. Electrical traps

In the case that a cell is very sensitive to physical stresses placed on the membrane, electrical methods of cell capture can be utilized. Toriello et al. developed a microfluidic system that consisted of a flow cell with a series of gold electrodes throughout. The gold electrodes were covered in an oxide layer, leaving an array of 16 um2 exposed gold pads, which were capable of binding to the single cells flowed through the system that are labeled with a thiol functional group. 65

In order to electrically capture cells without the use of cell labeling, it becomes necessary to utilize the dielectrophoretic (DEP) force that is generated when a nonuniform electric field acts on a particle. Das et al. demonstrated that DEP electrodes coated on a microscope slide could trap different types of cells directly from cell suspension on the slide.66 In terms of single cell trapping, Jaeger et al. employed negative DEP (nDEP) to trap a single yeast cell without contact in an electric field cage for single cell proliferation study.67 Similarly, Thomas et al. developed concentric ring nDEP traps to both hold the selected cell in place while repelling other cells in the flow system. 68 DEP traps have been further coupled with downstream cell detection methods. Single cell Raman spectra (SCRS) could be obtained by employing DEP to trap specific single cells for Raman detection (Fig. 1C).69–71 In addition, immobilizing a single HeLa cell by DEP for impedance measurement has been demonstrated by Chen et al. using DEP as a medium for both liquid manipulation and cell capture on a digital microfluidic device. 72

2.4. Optical traps

Optical tweezers, formed by a highly focused laser beam, offer a contactless trapping force able to hold a single cell in a fluidic medium. Xie et al. demonstrated the trapping of single living red blood cells, yeast cells, and bacterial cells using low-power optical tweezers for Raman spectroscopy acquisition.73, 74 Furthermore, optical tweezers have been integrated into microfluidic systems to allow label-free identification and sorting of single cells. Specific single cells were first identified using Raman spectra then trapped and moved from cell suspension (Fig. 1D). 75–77 A combination of optical tweezers and DEP, termed optoelectronic tweezers (OET), has been developed to manipulate single cells.78 Huang et al. designed an optoelectronic tweezer based microfluidic system that can optically select a specific cell from the population and move it to a separate channel. Once all of the channels are loaded with single cells, then the cells can be flushed off chip for further analysis. 79

2.5. Droplets

Droplet technologies are becoming increasingly popular with their ability to quickly and cheaply encapsulate single cells and provide an ideal micro-reactor.7, 8 Single cell capture technologies for droplet systems typically consist of generating droplets from a statistically dilute suspension of cells.80 With the advantage of high-throughput, droplets have been utilized to perform a variety of biological assays at the single cell level, including single cell cultivation,81–83 electroporation,84 antibody detection,85 enzyme screening,86, 87 drug screening,88 PCR,89, 90 reverse transcription for sequencing (RNA-seq),9, 11 whole-genome amplification,91, 92 and chromatin immunoprecipitation for sequencing (ChIP-seq).10

The difficulty that arises from using a statistically dilute suspension of cells is the inherent variability of the droplet contents. In order to produce high quality single cell droplet studies it is important to maximize the number of droplets containing a single cell, while minimizing empty droplets and droplets containing multiple cells. Passive methods relying on optimized channel designs have been developed to improve the rate of single cell droplets in all generated droplets.93–96 Chabert et al. presented a microfluidic device for single cell droplet encapsulation and hydrodynamic sorting for high reliability. The system took advantage of Rayleigh-Plateau instability in a flow constriction to form the droplets, where they were sorted by hydrodynamic forces. The system was capable of sorting 70–80% of the encapsulated cells with low incidence of multiple cell encapsulation and even fewer empty droplets. If integrated with other droplet technologies, this system could improve the quality of data while reducing the operating cost per cell. 95 Another method to reduce the variability of single cell encapsulation in droplet based systems is to improve the efficiency of single cell loading. Edd et al. demonstrated a microfluidic system capable of altering the single cell loading efficiency of generated droplets by utilizing inertial sorting to generate two trains of single cells in the loading channel (Fig. 1E). This self-organization of cells allows for an almost doubled fraction of droplets containing single cells when compared to a Poisson distribution. 96 Kemna et al. introduced Dean forces to order cells in microchannels before being encapsulated into droplets. With the aid of the cell ordering, ~80% of formed droplets contain single cells without compromising cell viability.94

Active methods to obtain single cell droplets are based on sorting single cell droplets from other generated droplets. We developed a droplet sorting platform that integrated a fluorescence signal processing system and a solenoid valve, which could identify the number of cells in an individual droplet and sort droplets containing a specific number of cells.97 This platform demonstrated high efficiency and accuracy for sorting droplets with fluorescent beads or lightly stained cells. Similarly, Wu et al. demonstrated an active droplet sorter which used hydrodynamic gated injection that was formed by a pressure difference among different microchannels. A single cell droplet rate of 94.1% has been obtained after droplet sorting. 98 Recently, Zhang et al. presented a droplet microfluidic platform that prepared single cell samples in the type of one-cell-in-one-tube. This platform included cell-encapsulated droplet generation, single cell droplet manual identification, sorting by solenoid valve suction force, and dispensing from microfluidic chip into collection tubes via a capillary embedded in the microchannel. 99 Single cell analyses including cultivation, real-time quantitative PCR, reverse transcription PCR, and MDA for sequencing have been demonstrated based on single cell samples prepared by this platform.

2.6. Microwells

Single cell isolation through the use of microwells uses either a specially sized well, a modified surface, and/or a statistically dilute suspension of cells to seed single cell microwells. Relying on microfabrication technology, parallel microwells can be easily made and enable high-throughput single cell analysis.100 Chin et al. demonstrated the fabrication of ~10,000 SU-8 microwells on a glass coverslip and its application for long-term and quantitative analysis of single cell stem cell proliferation.101 The strategies of cell recovery from microwells have been further developed in other studies. 102–104 Guo et al. developed an array of conical nanopores integrated in a microfluidic device that could not only selectively trap and isolate cyanobacteria from a mixed population containing chlamydomonas, but also release the trapped bacteria when the flow was inverted.103 In order to improve single cell capture efficiency, Faenza et al. developed a microwell platform coupled with DEP, in which DEP would provide focusing and patterning of single cells in microwells. Deterministic, not statistical, patterning of cells was used in this platform, achieving high cell trapping yield (>83%).105 Huang et al. demonstrated the use of reverse conical microwells in conjuction with the application of a centrifugal force, which allowed for 90% occupancy in only a few seconds.106 In addition to single cell trapping function, microwells could also act as microreactors for further single cell examination.107, 108

Surface modification has been utilized for cell trapping without complicated fabrication of cell-sized microwells.109–111 Lin et al. made an array of hydrophilic patterns on a hydrophobic glass substrate, which would rapidly form discrete aqueous droplets bearing seeded single Escherichia coli bacterial cells.109 These cell-seeded aqueous droplets have been further used as reaction chambers for real-time PCR of single cells.111 By combining the use of a surface modification with specifically sized micro-wells, it is possible to improve the efficiency and have a more defined geometry. Revzin et al. reported a polyethylene glycol (PEG) microwell array modified with T-cell specific anti-CD5 antibody to immobilize single T-lymphocytes, achieving 95% occupancy (Fig. 1F).112 Similarly, Chen et al. developed a microfluidic microwell array coated with cell specific aptamer that was capable of isolating and capturing single cells from a mixture. 113 Lin et al. combined surface modification with hydrodynamic cell traps to adhere cells to a protein micro-pattern in a controlled manner. The use of a removable hydrodynamic trap allowed for controllable paired positioning of cells at a higher frequency than random seeding would allow. 114

3. Physical analysis

3.1. Deformability

Many techniques that differentiate between cells of different types, phenotypes, and cell states require the use of fluorescent markers or antibodies, which can change the physiology of the single cell. For this reason, it is useful to study the mechanical properties of the membrane for differentiating cell states. A variety of microfluidic devices and perturbation techniques have been developed to characterize deformability of cells and have been summarized previously,115 including constriction channel,116–118 fluid stress,118, 119 optical stretcher,120, 121 electro-deformation,122, 123 electroporation,124 and microfluidic pipette aspiration.125, 126

Lincoln et al. demonstrated a deformability-based flow cytometry system by coupling an optical stretcher with a microfluidic device, which achieved classification of red blood cells (RBCs) and polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) based on their optical deformability.127 A biophysical flow cytometry has been developed by Rosenbluth et al. to detect differences between normal and aberrant blood cells based on their transit times flowing through microfluidic capillary microchannels 128. Similarly, Gabriele et al. developed a microfluidic device that consisted of a parallel analysis channel and bypass channel. 129 The analysis channel contained a series of constrictions and expansions which could differentiate cells by the amount of time it took to pass through the constriction structure. Hur et al. developed a microfluidic system capable of separation of single cells based on their deformability without the use of markers. 130 The deformability could be indirectly quantified by studying the equilibrium position of the cells in a focusing channel before they were separated into different populations. This approach could be applied at high-throughput and of great use when differentiating phenotypically similar cells with different deformabilities.

In order to better characterize the mechanical deformability of single cells it becomes important to induce greater shear stress in the system. Gossett et al. described a microfluidic system capable of high-throughput analysis of single cell deformability. 131 Using a cross shaped channel and driving high flow rates from opposite sides, single cells were deformed at great strain rates. The deformation was observed and analyzed allowing for the markerless classification of single cells into different disease states. Tse et al. utilized their previous microfluidic stretching system to also perform high-throughput markerless classification of single cells (Fig. 2A).132 The system was able to differentiate between various cell types with high confidence. This was useful in differentiating malignant cancer cells from a population. Improving upon their previous work, Dundani et al. developed a microfluidic hydrodynamic cell stretching platform which was able to perform two different stretching measurements at different strain rates. 133 This provided complementary data sets for more accurate classification of mechanical phenotypes.

Fig. 2.

Microfluidics-based physical analysis of single cells. (A) Single-cell deformability cytometry. Reprinted with permission from H. T. K. Tse, et al., Sci. Transl. Med., 2013, 5, 212ra163–212ra163. Copyright 2013 The American Association for the Advancement of Science. (B) Single-cell impedance cytometry. Reprinted with permission from D. Holmes, et al., Lab Chip, 2009, 9, 2881–2889. Copyright 2009 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

We developed a microfluidics-based electroporative flow cytometry (EFC) platform to capture swelling of cell during electroporation, which provided a new method to study single-cell deformability/biomechanics.124 Otto et al. demonstrated a real-time deformability cytometry without using shear stresses and pressure gradients. 134 Instead, a microchannel constriction induced cell deformation which was detected by a CMOS camera for continuous and real-time image acquisition. The concept of studying mechanical deformability can be applied further to non-mammalian cell types. Lei et al. developed a flow focusing microfluidic device capable of classifying microalgae into different phenotypes based on mechanical and cytometric analysis under a multitude of on-chip culture conditions. 135

3.2. Impedance

Impedance cytometry is an invaluable tool in differentiating cells in a clinical setting. The ability to produce highly automated systems for differentiating important cell types can have a positive effect on point-of-care medicine. Sohn et al. reported a capacitance cytometry that could measure the capacitance of cells as they flowed through the electrodes one by one. 136 They found a linear relationship between the DNA content and the capacitance of a eukaryotic cell. Gawad et al. developed a coplanar electrode-based microfluidic device for impedance measurements of single cells or particles with different sizes or types. 137 During their study, they also compared three types of electrode geometries using simulations. Single cell and particle impedance cytometry has experienced rapid growth in recent years (Fig. 2B).138–142 New developments have been focused on implementing rapid and high-throughput examination 143–145, high sensitivity,143, 146–148, multi-modal measurements,149–151 and clinical field applications. 152–159 Bashir’s group has demonstrated a series of studies in HIV/AIDS diagnostics based on microfluidic impedance cell counting.160, 161 Ang et al. described a microfluidic flow cytometer with high-sensitivity graphene transistors capable of sensing malaria infected red blood cells. 153 The flow cell contained a graphene transistor functionalized with CD36 receptors to selectively capture malaria infected cells. The conductance was then measured before the cell was released. The system was able to differentiate between two different phases of malaria infection with high confidence. Islam et al. developed a method of detection and electrical profiling of single tumor cells from whole blood in a microfluidic device. 154 Tumor cells were found to have a higher translocation time when using nanotextured channels while most blood cells were largely unaffected. Based on translocation time and peak amplitude of the electrical measurements, cancer cells were easily identified from whole blood. Hong et al. demonstrated a microfluidic trap-and-measure device capable of performing single-cell electrical impedance spectroscopy in order to differentiate cell types using different voltages. 156 Using their system, they were able to distinguish among 4 different cell types and cancer pathological states. Similarly, Zhou et al. described hydrodynamic trapping of single cells and use of electrodes for impedance spectroscopy. 155 They could quantitatively analyze differentiation of mESCs at different time points. This system could also be adapted to study dynamic changes in the properties of cells over a long period of time.

3.3. Migration

The study of cell migration dynamics is crucial in understanding invasive and malignant diseases such as cancer. Zheng et al. demonstrated a microfluidic platform for cell migration analysis at single cell resolution.162 The system utilized large micromechanical valves inside a channel, which when actuated created a cell free area after the channel is loaded with cells. When the valve was opened, the system could be used to study the migration of the cells into these open areas. Unfortunately cells in vivo migrate in three dimensions could not be measured in Zheng’s device. To study this, Nguyen et al. developed a multiplexed microfluidic system for electrical cell–substrate impedance sensing. 163 The system was able to investigate 2D and 3D cell migration in addition to identifying cellular activities using electrical parameters on a single cell level. In order to study the competing migration between two different cell species, Zheng et al. developed a microfluidic system for co-culture of two cell types with 16 parallel cultures. 162 The system had a valve separating the two cell cultures. When the physical separation between the populations was removed, this allowed for migration and infiltration studies.

3.4. Other physical parameters

Exploring the physical characteristics such as the shape and volume of cells, Lee et al. utilized their quartz nanopillar device to isolate single circulating tumor cells from whole blood. 164 The cells were then examined using laser scanning cytometry to determine cell shape or circularity. Riordon et al. developed a microfluidic device to measure the volume of a single cell during cell growth in suspension by controllably passing the cell back and forth over a set of electrodes. 165 Investigating the weight of intracellular components, Olcum et al. demonstrated a microfluidic system capable of weighing nanoparticles. 166 This was applied to single cell analysis of an exome self-assembled nanoparticle mass which could be used to characterize cell types.

4. Chemical analysis

4.1. Electrophoresis

Capillary electrophoresis (CE) coupled with laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) has been widely used to analyze cellular contents.167–169 McClain et al. integrated CE into a microfluidic device, in which single cells were lysed at the lysis intersection and cell lysate was separated in the channel by application of a high voltage. 170 The fluorescent labeled cellular contents subsequently underwent LIF detection. We further optimized the chip design to obtain different field intensity at the lysis124, 171 and electrophoresis sections, which could alleviate local Joule heating caused by high field intensity (Fig. 3A).172 Instead of electrical lysis, Phillips et al. integrated laser-generated cavitation bubble based cell lysis into a microfluidic electrophoresis chip. 173 The device was able to achieve robust and continuous single cell content analysis. Instead of LIF, chemiluminescence detection (CL) was coupled with microchip electrophoresis to detect glutathione (GSH) in single human red blood cells with about 100 times greater sensitivity.174 In addition, western blotting has also been coupled with CE to allow multiplexed protein detection.175 A high throughput of 38 cells per minute has been achieved by introducing sheath-flow streams to focus labeled cells. 176 This was used to analyze reduced GSH and reactive oxygen species in single erythrocytes. Cells trapped in microwells have also been subject to automated and high-throughput CE analysis.177, 178 Microfluidic CE has also been used for analysis of neurotransmitters in single rat pheochromocytoma (PC 12) cells179 and peptidase activity in single tumor cells,180 in addition to analysis of small-molecule metabolites,181 sphingosine kinase activity,182 and Akt activity in single cells.183

Fig. 3.

Microfluidics-based chemical analysis of single cells. (A) Chemical cytometry. Reprinted with permission from H. -Y. Wang, et al., Chem. Commun., 2006, 33, 3528–3530. Copyright 2006 The Royal Society of Chemistry. (B) TIRF (Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence) flow cytometry. Reprinted with permission from J. Wang, et al., Anal. Chem., 2008, 80, 9840–9844. Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society. (C) CARS (Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Spectroscopy) cytometry. Reprinted with permission from H. -W. Wang, et al., Opt. Express, 2008, 16, 5782–5789. Copyright 2008 Optical Society of America. (D) Mass cytometry. Reprinted with permission from S. C. Bendall, et al., Science, 2011, 332, 687–696. Copyright 2011 The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

4.2. Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry based on detecting fluorescence emitted from flowing single cells has been widely used to study single cell intracellular calcium,44, 184, 185 proteins and cytokines,22, 186, 187 DNA content,188 and apoptosis189, 190. We have developed specialized flow cytometric technologies on microfluidic platforms for applications other than quantification of fluorescent species. For instance, we combined electroporation with flow cytometry, denoted as Electroporative Flow Cytometry (EFC), in a microfluidic device to study the translocation of a protein-tyrosine kinase to the plasma membrane in B cells.191 EFC took advantage of the fact that the rate of electroporation-based release of intracellular molecules depends on their subcellular locations (e.g. a protein in the nucleus is harder to release than the same protein of cytosolic localization during electroporation, which breaches plasma membrane). Thus the protein subcellular localization quantitatively correlated with the amount of protein loss during electroporation (or other release methods). Other than examining translocation to cell membrane, we also used it to study NF-kB nucleocytoplasmic transport at the single cell level.187, 192 We also developed total internal reflection fluorescence flow cytometry (TIRF-FC) which could be utilized to quantitatively examine events at the plasma membrane region by using a TIRF setup and a microfluidic constriction region where cells were forced to be in close contact with the substrate surface (Fig. 3B)193. TIRF-FC was run at a throughput of ~100–150 cells per second and used to detect protein translocations194 and examine endocytosis-based uptake of quantum dots into cells195.

Baumgarth et al. reported a multicolor flow cytometer, which could detect eleven colors of fluorescence plus two scattered light parameters on each single cell.196 Krutzik et al. developed a fluorescent cell barcoding (FCB) technique which enabled cells to be labeled with multiple fluorophores of different intensities.22 This allowed them to achieve high-throughput flow cytometry while measuring fifteen or more fluorescent parameters of single cells. 23

The first microfabricated fluorescence-activated cell sorter (μFACS) was developed by Fu et al.197 Miniaturized flow cytometry has been integrated in a microfluidic device by Kruger et al. for FACS.198 Since then, different kinds of microfluidic techniques have been used to separate target cells after being identified by fluorescence. For instance, Holmes et al. demonstrated a high-speed microparticle sorting microfluidic platform that employed DEP to deflect fluorescent particles in the microchannel.199 Wang et al. utilized optical force for sorting of HeLa cells expressing a fluorescent protein to achieve fluorescence-activated microfluidic cell sorting.200 Chiou’s group developed a pulsed laser triggered fluorescence activated cell sorter (PLACS), which could achieve throughput of 20,000 cells/s with 37% sorting purity and >90% purity at throughput of 1,500 cells/s.201 Hydrodynamic switching originating from pneumatic microvalves,202 off-chip valves,203 or piezoelectric (PZT) actuators204 have also been employed to isolate single cells after fluorescence detection.

4.3. Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy that provides information on chemical signature is a valuable tool for analysis of single cells. Single cell Raman spectroscopy (SCRS) provides a wealth of information for classification of cell types,205–208 physiological states,209–212 and environmental conditions.213–215 These have been reviewed previously. 216, 217

By integrating SCRS-based analysis into microfluidic systems, Raman cell counting, Raman flow cytometry, and Raman-activated cell sorting (RACS) have been developed. Li et al. showed that 12C- and 13C-cyanobacterial cells could be counted in a microfluidic device by using resonance Raman spectra to improve the weak spontaneous Raman signal of single cells.218 Nolan et al. pioneered the method of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) flow cytometry.219, 220 For instance, Sebba et al. developed a high-throughput SERS flow cytometry with nanoparticles labeled with one of three chromophores: oxazine 170, thionin, or malachite green. 220 This allowed for SERS detection within submillisecond time. Collaborating with Ji-xin Cheng group, we incorporated laser-scanning coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS) detection into a microfluidic device (i.e. microfluidic CARS flow cytometry).221 We demonstrated its use to measure the size distribution of adipocytes harvested from mice fat tissue (Fig. 3C).221 Subsequent works coupled multiplexed CARS with flow cytometry to reach a large spectral range by exciting multiple Raman transitions.222, 223 Stimulated Raman spectroscopy (SRS) could significantly improve Raman detection sensitivity. SRS flow cytometry allowed 200,000 Raman spectra to be acquired within one second and the throughput could achieve 11,000 particles per second 224. Using SRS flow cytometry, Zhang et al. has demonstrated the classification of 3T3-L1 cells based on their differentiation states.224

Other than Raman flow cytometry, RACS has also been developed to identify and isolate target cells from cell suspension based on their Raman spectra.71, 75, 76, 225 Lau et al. developed an optofluidic RACS platform by using optical tweezers to trap single cells for acquisition of Raman spectra before moving the cell of interest into a collection channel.76 Zhang et al. reported a more automated RACS system with cell sorting of higher throughput, in which they used positive dielectrophoresis (pDEP) to trap single cells for Raman acquisition. 71 The target cells were then isolated in a collection chamber using solenoid valve suction.

4.4. Mass spectroscopy

Different types of mass spectroscopy have been used in the field of single cell analysis, including single probe mass spectrometry,226 matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS),227, 228 secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS),229 electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS),230 and combined methodologies.231 Utilizing microfluidic technology, a high-density microarray for mass spectrometry (MAMS) was produced by Urban et al. for single cell analysis using MALDI-MS. Furthermore, Xie et al. utilized a microfluidic frame and microporous membrane to selectively place single cells in a microwell array on an indium tin oxide coated glass slide. The array of cells were processed using MALDI-MS to study phospholipids in the single cells. 232 In addition, Mellors et al. demonstrated a microfluidic system integrating capillary electrophoresis and electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. 233 The system electrically lysed single cells, separated the cellular contents in the electrophoretic channel and passed the separated contents to the electrospray emitter to be characterized by mass spectrometry.233 Using inkjet single cell printing, Chen et al. was able to profile lipid fingerprints of single cells using probe electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. 234

In the past decade, single cell mass cytometry, or cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF), has seen dramatic improvement for multi-parameter analysis of cells.235–238 This technique was first reported by Bandura et al., who used an inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry to conduct simultaneous measurement of 20 antigens in single cells of leukemia cell lines and leukemia patient samples.239 Recently, Porpiglia et al. reported that CyTOF could simultaneously measure up to 50 parameters in single cell analysis.240 Using time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry with a single cell array, Huang et al. were able to study phenotypic alterations through cell apoptosis.241 CyTOF has been widely used in single cell analysis by Nolan’s group (Fig. 3D)242–244 as well as other groups.240, 245

5. Molecular biology analysis

5.1. Immunoassays

Microwells

Microwell-based single cell immunoassay was a microengraving-based method first developed by Love et al. 246 After loading cells into a microwell array engraved on a PDMS slab, the array was bound to a slide of glass coated with antigen. Primary antibody produced by the cells was captured onto the substrate and fluorescently labeled secondary antibody was added. The secondary antibody targeted the primary antibody and indicated the amount of antigen-specific antibody secreted by single cells. This method was used to characterize the antibodies produced by primary B cells in terms of specificity, isotype, and apparent affinity at single cell level.247 The cytokine secretion from single cells has also been analyzed.204, 248–250 Combined with the cellular barcoding technique, the microengraving method achieved simultaneous analysis of thousands of single cells.251

Herr’s group developed a microwell-based single cell western blotting method that detected single cell proteins with high specificity. 252–254 The method integrated the multiple processes of single cell loading in microwells, on-chip lysis, gel electrophoresis, blotting, and antibody probing. Whole cell imaging was further incorporated in single cell western blotting to demonstrate simultaneous phenotypic and proteomic analysis of single cells.255

Microchambers

Eyer et al. integrated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) into a microchamber. This allowed for single cell capture, lysis, and analysis of proteins, secondary messengers, or metabolites. The system has been demonstrated to quantify the enzyme GAPDH in single U937 cells and HEK 293 cells. 256 Sun et al. demonstrated a microfluidic cell array chip for immunocytochemistry, termed microfluidic image cytometry (MIC). They achieved multiparametric single cell measurements (simultaneous quantification of four proteins). 257, 258 There were many other methods for analyzing protein expression 259 and spatial distribution 260 in single cells using fluorescence.

Protein barcodes are multiple strips of antibodies capable of capturing specific proteins. When coupled with fluorescence detection, they provided a simple method for quantifying proteins for a number of loci. A single-cell barcode chip was developed by Heath’s group for quantitative and multiplexed analysis of intracellular proteins from single cells isolated in microchambers containing antibody barcode array. Shin et al. first developed a method for patterning microfluidic platforms using DNA microarrays which were subsequently converted into antibody arrays for protein capture and quantification. 261 Using this method, they were able to develop a microfluidic system for capturing single cells and profiling their protein secretions. 262 Lu et al. expanded upon previous work, developing a highly paralleled protein barcode assay for secretomic analysis of single cells. 263 Using 14-protein barcodes in a microchamber array (>5000 microchambers) allowed for simultaneous analysis of thousands of single cells. 263 Elitas et al. further improved the system to allow for detection of up to 16 different proteins. 264 Finally, Lu et al. expanded upon their barcode secretomic analysis platform by multiplexing the protein barcodes with multiple fluorescent signals. 265 This enabled analysis of up to 45 different proteins at the single cell level in a highly multiplexed assay (Fig. 4A). Many groups have demonstrated the use of protein barcoding for high-throughput single cell protein analysis.266 Shi et al. developed a microfluidic system for profiling signaling pathways that integrated single cell chambers and a protein detecting antibody barcode, which could detect and quantify nine proteins released from lysed single cells. 64 Ma et al. demonstrated an assay for high-throughput secretomic analysis at the single cell level. The system used antibody barcodes in over 1,000 microchambers and allowed for simultaneous analysis of up to 10 proteins.267 Deng et al. created a microfluidic system to isolate circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from whole blood using ssDNA encoded antibodies to absorb CTCs. These complexes were then captured on a functionalized surface in the microfluidic device. After purification, the CTCs were loaded onto a single cell barcode chip for fluorescent protein analysis. 53

Fig. 4.

Single cell analysis based on immunoassays and PCR. (A) Single-cell immunoassay. Reprinted with permission from Y. Lu, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 2015, 112, E607–E615. Copyright 2015 National Academy of Sciences. (B) PCR-based single-locus analysis. Reprinted with permission from D. J. Eastburn, et al., Nucleic Acids Res., 2014, 42, e128. Copyright 2014 Oxford University Press.

Droplets

There are a number of reports of immunoassays performed in microfluidic droplets. Konry et al. demonstrated a droplet-based approach to detect protein secretions by co-encapsulating secreting T cells with capture-antibody-modified microspheres and fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. Using this method, IL-10 cytokine secretion in single CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells has been detected.268 Akbari et al. developed a droplet-based heterogeneous single cell immunoassay that could be used to screen cells producing antigen-specific antibodies at the single cell level.269 By using digital microfluidics, Ng et al. created an automated system for cell culture, stimulation, and immunochemistry study of single cells. The digital microfluidic system allowed for very short pulsing of stimuli and subsequent examination of the phosphorylation state of platelet-derived growth factor and signaling protein Akt.270

5.2. PCR-based single-locus analysis

PCR-based assays target specific genes in the single cell transcriptome, genome and epigenome. These assays have been performed on single cells trapped in microwells,271 microchambers,272, 273 and droplets. 89, 274, 275 Gong et al. demonstrated a microwell-based protocol for single cell detection of gene expression by single step RT-PCR of mRNA transcripts. The system deposited a dilute cell suspension with PCR mix into a microwell array for on-chip PCR and fluorescence detection. 271 Zhang et al. developed a microarray with 900 microwells that was capable of performing fully integrated liquid phase purification of DNA or RNA and qPCR of single bacterial cells. This microarray achieved 87% and 71% single cell positive amplification for DNA and RNA, respectively. 276 This platform was also employed to investigate bacterial adhesion to single host cells. 276 With hydrophilic-surface-based single cell trapping, Shi et al.111 and Zhu et al. 277 demonstrated real-time PCR assay of single bacterial cells and reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) assay of single Huh-7 cells, respectively. White et al. developed a fully integrated device consisting of a series of pneumatic-valve-formed microchambers to capture single cells, which were then washed, lysed, and reverse transcribed. PCR mix was loaded into the chambers for real time qPCR to measure the gene expression. 272 White et al. then expanded upon their previous high-throughput platform by adding a digital PCR assay instead of the qPCR chamber, reaching 204,000 PCR reactions per run. This approach made it possible to provide direct quantification of mRNA transcripts and microRNAs on a high-throughput platform. 62

Kumaresan et al. reported a droplet-based microfluidic platform that could generate droplets containing single cells, primer-attached beads, and PCR mix for PCR analysis of a specific gene in single cells.275 Combined with fluorescent microscope analysis, single cell agarose droplet PCR has been used to digitally detect rare pathogen with high sensitivity and throughput 278 and transcriptional profiling of single mammalian cells with a throughput of ~50,000 individual cells per run.279 It was reported that CE could also be coupled with single cell droplet PCR for analysis of short tandem repeat (STR) in forensic identification. 89 Combining single-cell droplet PCR with DEP-based droplet sorting, PCR-activated cell sorting (PACS) was able to separate droplets containing target nucleic acids within single cells after PCR. 274 This was utilized for enrichment of genomes and transcripts of prostate cancer cells (Fig. 4B). PACS has further been used to sort rare microbes90 or specific virus280, 281 based on their genomes from a mixed population without requiring cultivation.

5.3. Transcriptomic, genomic and epigenomic analysis

We have recently written a review specifically on microfluidics-based whole-genome analysis assays that included transcriptomic, genomic and epigenomic analysis of single cells.282 Thus we will only highlight some of the most important works on omic analysis of single cells in here.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides the ability to classify the entirety of the transcriptome of a single cell. Streets et al. developed a multiplexed assay to capture single cells, perform lysis, reverse transcription, polyA tailing, primer digestion, and second strand cDNA synthesis. 63 Other steps such as amplification, purification, library preparation, and sequencing were all performed off-chip. This device utilized multiple chambers to increase the reaction volume with every step to achieve proper concentrations and produce such high quality cDNA for sequencing that the majority of the bulk transcriptome could be recreated using the transcriptomes of 10 single cells. Using mESCs, this method was able to detect an average of 8,000 genes per cell, which was approximately 65% of the bulk samples detection. 63 A commercially available Fluidigm C1 microchamber-based platform has also been widely used for RNA-seq. It can perform 96 parallel assays of single cell capture, lysis, reverse transcription, and preamplification. 283 The platform has been utilized to study RNA sequencing for a number of different biological outcomes such as understanding cellular taxonomy of neurons, 284 cell reprogramming, 284 genetic cause of disease,285 and constructing lineage hierarchies. 283

Microwells have also been utilized as reactors to process single cells in preparation for RNA sequencing. DeKosky et al. fabricated 170,000 wells of 125-pl volume within a PDMS slide for containing single cells and poly(dT) magnetic beads. After annealing, the beads were collected and emulsified for cDNA synthesis. Sequencing was performed after linkage PCR.286 Fan et al. demonstrated that barcoded beads loaded into microwells were able to distinguish each single cell and each transcript copy. 287 By this method, one could examine a few thousand cells simultaneously with high sensitivity. Bose et al. integrated the microwells in a microfluidic platform, which allowed for easy reagent loading and diffusion-based fluid exchange. 288 Furthermore, by using sealing oil, this system was able to reduce crosstalk between samples by physically segregating the microwells during lysis and the mRNA hybridization. The average sample using this method detected a mean of 635 genes per cell using human cancer cell lines. Similarly, a more automated microwell platform has been developed for single cell RNA-seq.289 Recently, a portable and low-cost platform, named Seq-Well was reported for massively parallel single cell RNA-seq, in which ~86,000 sub-nanoliter wells within a slide of PDMS could achieve ~95% single-bead loading efficiency and 80% single cell capture efficiency. 290 A semipermeable membrane was used to seal the microwells that would trap biological macromolecules within the microwells while enabling rapid solution exchange.

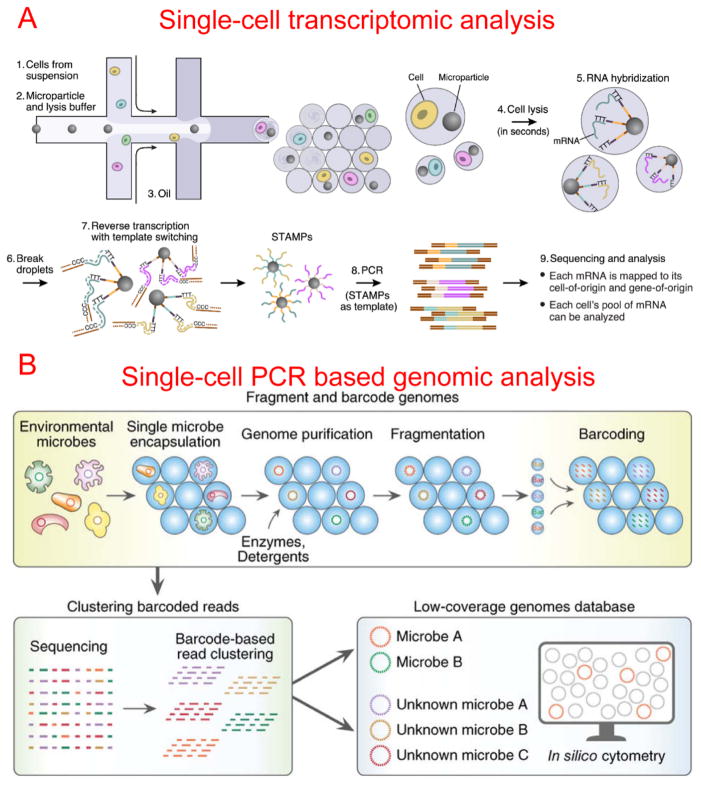

Two microfluidic droplet-based RNA-seq devices have been reported in 2015. Macosko et al. utilized nanoliter droplets to combine single cells together with barcoded beads for analysis of all mRNAs from a single cell, termed Drop-seq.9 Barcoded beads have been carefully designed with a priming site for downstream PCR and sequencing, a cell barcode sequence for identifying different cells, a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) for distinguishing different mRNA transcripts, and an oligo-dT sequencing for capture of mRNAs (Fig. 5A). Drop-seq has been used to characterize transcriptomes and find 39 distinct cell populations with a high-throughput.9 Instead of barcoded beads, Klein et al. reported using barcoded hydrogel microspheres co-encapsulated in droplets with single cells and RT mix, termed inDrop11. The hydrogel microspheres contained T7 promoter, sequencing primer, barcodes, synthesis adaptor, UMI, and poly-T primer. It has been demonstrated to profile the whole transcriptome of mESCs with a throughput of over 10,000 cells per run.11

Fig. 5.

Single-cell transcriptomic and genomic analysis. (A) Single-cell transcriptomic analysis. Reprinted with permission from E. Z. Macosko, et al., Cell, 2015, 161, 1202–1214. Copyright 2015 Elsevier. (B) Single-cell genomic analysis. Reprinted with permission from F. Lan, et al., Nat. Biotechnol., 2017, 35, 640–646. Copyright 2017 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

It is often advantageous to perform whole-genome amplification in order to study the DNA of a single cell. Multiple displacement amplification (MDA) is a non-PCR-based method for whole-genome amplification which has been known to generate less nonspecific amplification artifacts compared with PCR amplification. The first microfluidic single cell MDA was reported by Marcy et al., in which multiple single cell processing was achieved by utilizing microchambers formed by integrated valves. 59 Single E.coli MDA was performed with a small volume of 60 nl that could reduce background amplification and improve amplification efficiency. This platform was further used to amplify and analyze genomes of uncultivated, rare single microbial cells,291 as well as single sperm cells.61 Instead of MDA, Yu et al. developed a microfluidic device that was able to perform whole genome amplification utilizing multiple annealing and looping based amplification cycles (MALBEC). After single cell isolation, lysis, MALBEC preamplification, and MALBEC, PCR was performed, achieving lower contamination and improved amplification uniformity. 292

By using a commercially available liquid dispensing platform, Leung et al. created nanoliter droplets on a planar substrate as single cell MDA reactors. The method was able to achieve up to 80% coverage at the single cell level. 293 Gole et al. developed microwell displacement amplification system (MIDAS) to perform a single cell MDA reaction within a 12 nl volume, achieving highly uniform genome coverage and low amplification bias.107 By reducing the amplification volume even further, Fu et al. demonstrated single cell whole genome amplification with reduced amplification bias while utilizing MDA. 92 This was done by encapsulating fragments of genomic DNA in picoliter droplets which could then be isothermally amplified to saturation.92 Recently, Lan et al. developed an ultra-high-throughput droplet-microfluidic platform to prepare single-cell genomes for sequencing, which achieved single-cell genomic sequencing (SiC-seq) at >50000 cells per run and the sequencing of large populations of single cells (Fig. 5B).294

Microfluidic epigenomic analysis has just been emerging. We developed microfluidic oscillatory washing based chromatin immunoprecipitation (MOWChIP-seq) to examine genome-wide histone modifications using as few as 100 cells295. Our technology used a packed bed of beads and oscillatory washing to achieve adsorption of ChIP DNA with high efficiency approaching the theoretical limit. Drop-ChIP was the first microfluidic single cell ChIP-seq tool.10 Chromatin fragments from single cells were encapsulated and processed in droplets to tag unique barcodes to chromatin from individual cells. Then ChIP was conducted at the population level. Drop-ChIP was able to reveal variation among cells. However the downside was that each cell only yielded about 1000 reads which were not enough to provide high resolution on genome-wide features.

6. Conclusions

Many microfluidic technologies have been developed over the past decade for the analysis of single cells. The devices have become increasingly integrated, high-throughput, and sensitive. Future generations of microfluidic single cell tools will trend towards high-throughput and multi-modal assays with full workflow integration and limited operator interaction. We predict that molecular biology assays will be a significant point of growth in the near future, given their direct relevance to clinical assessment and decision-making. With decreasing cost associated with next-generation sequencing, single-cell omic analysis will also see substantial interests and development. The application of these single cell technologies will enable the analysis and profiling of various cell and tissue types in a human body, as well as yielding improved understanding and resolution of cell signaling pathways and phenotypic/genotypic changes. Finally, there will likely be great strives made in the field of personalized and precision medicine with the widespread availability of single cell profiling technologies, specifically with regard to rare cell types such as circulating tumor cells and cancer stem cells.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from National Institutes of Health grants HG008623, CA214176, EB017235, and HG009256.

Biographies

Travis Murphy received his B.S. in chemical engineering with honors from Virginia Tech in 2014. He is now a Ph.D. candidate in chemical engineering at Virginia Tech with Professor Chang Lu. His research interests include developing high-throughput microfluidic technologies as well as downstream integration and automation of microfluidic systems specifically in the area of epigenomic analysis.

Qiang Zhang is currently a PhD student in the Department of Chemical Engineering at Virginia Tech. He obtained his B.S and M.S. from Qingdao University. His research interests include droplet microfluidics, bisulfite sequencing, and single-cell analysis.

Lynette Naler is a graduate student in chemical engineering at Virginia Tech. Lynette obtained her B.S. in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and B.A. in Computer Science from Johns Hopkins University in 2014. She then spent two years as a research fellow at the National Institute on Aging. Lynette is currently a member of Prof. Chang Lu’s group where she is working on a microfluidic technology for the study of epigenetics using low-input samples.

Dr. Sai Ma is a postdoctoral associate at Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. He obtained his B.S. in Chemistry from Zhejiang University in 2011. He received his PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Virginia Tech in 2017 where his research in Dr. Chang Lu’s group was focused on developing microfluidic technologies for comprehensive genomic and epigenomic analysis. These technologies have been used to study neurological disease and brain development. After completing his PhD, he joined Broad Institute working with Dr. Jason Buenrostro and Dr. Aviv Regev where he is currently focused on developing high-throughput biological tools to systematically understand single cells.

Dr. Chang Lu is the Fred W. Bull professor of chemical engineering at Virginia Tech. Dr. Lu obtained his B.S. in Chemistry with honors from Peking University in 1998 and PhD in Chemical Engineering from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2002. He then spent 2 years as a postdoctoral associate in Applied Physics of Cornell University. His research has been in the general area of developing microfluidic technologies for molecular manipulation and analysis. Dr. Lu received Wallace Coulter Foundation Early Career Award, NSF CAREER Award, and VT Dean’s award for research excellence among a number of honors.

References

- 1.Whitesides GM. Nature. 2006;442:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nature05058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Ali J, Sorger PK, Jensen KF. Nature. 2006;442:403–411. doi: 10.1038/nature05063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorsen T, Maerkl SJ, Quake SR. Science. 2002;298:580–584. doi: 10.1126/science.1076996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unger MA, Chou HP, Thorsen T, Scherer A, Quake SR. Science. 2000;288:113. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teh SY, Lin R, Hung LH, Lee AP. Lab Chip. 2008;8:198–220. doi: 10.1039/b715524g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belder D. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:3521–3522. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joensson HN, Andersson Svahn H. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:12176–12192. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo MT, Rotem A, Heyman JA, Weitz DA. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2146–2155. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21147e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck EM, Trombetta JJ, Weitz DA, Sanes JR, Shalek AK, Regev A, McCarroll SA. Cell. 2015;161:1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotem A, Ram O, Shoresh N, Sperling RA, Goren A, Weitz DA, Bernstein BE. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:1165–1172. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein Allon M, Mazutis L, Akartuna I, Tallapragada N, Veres A, Li V, Peshkin L, Weitz David A, Kirschner Marc W. Cell. 2015;161:1187–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan F, Haliburton JR, Yuan A, Abate AR. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11784. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdelgawad M, Wheeler AR. Adv Mater. 2009;21:920–925. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi K, Ng AH, Fobel R, Wheeler AR. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2012;5:413–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-062011-143028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buettner F, Natarajan KN, Casale FP, Proserpio V, Scialdone A, Theis FJ, Teichmann SA, Marioni JC, Stegle O. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:155–160. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Junker JP, van Oudenaarden A. Cell. 2014;157:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver WM, Tseng P, Kunze A, Masaeli M, Chung AJ, Dudani JS, Kittur H, Kulkarni RP, Di Carlo D. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2014;25:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyamoto DT, Lee RJ, Stott SL, Ting DT, Wittner BS, Ulman M, Smas ME, Lord JB, Brannigan BW, Trautwein J, Bander NH, Wu CL, Sequist LV, Smith MR, Ramaswamy S, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:995–1003. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stott SL, Lee RJ, Nagrath S, Yu M, Miyamoto DT, Ulkus L, Inserra EJ, Ulman M, Springer S, Nakamura Z, Moore AL, Tsukrov DI, Kempner ME, Dahl DM, Wu CL, Iafrate AJ, Smith MR, Tompkins RG, Sequist LV, Toner M, Haber DA, Maheswaran S. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:25ra23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawson DA, Bhakta NR, Kessenbrock K, Prummel KD, Yu Y, Takai K, Zhou A, Eyob H, Balakrishnan S, Wang CY, Yaswen P, Goga A, Werb Z. Nature. 2015;526:131–135. doi: 10.1038/nature15260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen L, Tang F. Genome Biol. 2016;17:71. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0941-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krutzik PO, Nolan GP. Nat Methods. 2006;3:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nmeth872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krutzik PO, Crane JM, Clutter MR, Nolan GP. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:132–142. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang B, Wu H, Bhaya D, Grossman A, Granier S, Kobilka BK, Zare RN. Science. 2007;315:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1133992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeffries GD, Lorenz RM, Chiu DT. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9948–9954. doi: 10.1021/ac102173m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindstrom S, Eriksson M, Vazin T, Sandberg J, Lundeberg J, Frisen H, Andersson-Svahn J. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang K, Martiny AC, Reppas NB, Barry KW, Malek J, Chisholm SW, Church GM. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:680–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurimoto K, Yabuta Y, Ohinata Y, Saitou M. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:739–752. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potter NE, Ermini L, Papaemmanuil E, Cazzaniga G, Vijayaraghavan G, Titley I, Ford A, Campbell P, Kearney L, Greaves M. Genome Res. 2013;23:2115–2125. doi: 10.1101/gr.159913.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalerba P, Kalisky T, Sahoo D, Rajendran PS, Rothenberg ME, Leyrat AA, Sim S, Okamoto J, Johnston DM, Qian D, Zabala M, Bueno J, Neff NF, Wang J, Shelton AA, Visser B, Hisamori S, Shimono Y, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Clarke MF, Quake SR. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1120–1127. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espina V, Wulfkuhle JD, Calvert VS, VanMeter A, Zhou WD, Coukos G, Geho DH, Petricoin EF, Liotta LA. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:586–603. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding XY, Li P, Lin SCS, Stratton ZS, Nama N, Guo F, Slotcavage D, Mao XL, Shi JJ, Costanzo F, Huang TJ. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13:3626–3649. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50361e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franke T, Braunmuller S, Schmid L, Wixforth A, Weitz DA. Lab on a Chip. 2010;10:789–794. doi: 10.1039/b915522h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shields CW, Reyes CD, Lopez GP. Lab on a Chip. 2015;15:1230–1249. doi: 10.1039/c4lc01246a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li P, Mao ZM, Peng ZL, Zhou LL, Chen YC, Huang PH, Truica CI, Drabick JJ, El-Deiry WS, Dao M, Suresh S, Huang TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:4970–4975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504484112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huh D, Bahng JH, Ling Y, Wei HH, Kripfgans OD, Fowlkes JB, Grotberg JB, Takayama S. Anal Chem. 2007;79:1369–1376. doi: 10.1021/ac061542n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia N, Hunt TP, Mayers BT, Alsberg E, Whitesides GM, Westervelt RM, Ingber DE. Biomed Microdevices. 2006;8:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s10544-006-0033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pamme N, Wilhelm C. Lab Chip. 2006;6:974–980. doi: 10.1039/b604542a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saliba AE, Saias L, Psychari E, Minc N, Simon D, Bidard FC, Mathiot C, Pierga JY, Fraisier V, Salamero J, Saada V, Farace F, Vielh P, Malaquin L, Viovy JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14524–14529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001515107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lieu VH, House TA, Schwartz DT. Anal Chem. 2012;84:1963–1968. doi: 10.1021/ac203002z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanyeri M, Schroeder CM. Nano Lett. 2013;13:2357–2364. doi: 10.1021/nl4008437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karimi A, Yazdi S, Ardekani AM. Biomicrofluidics. 2013;7:21501. doi: 10.1063/1.4799787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Carlo D, Wu LY, Lee LP. Lab Chip. 2006;6:1445–1449. doi: 10.1039/b605937f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Li PC. Anal Chem. 2005;77:4315–4322. doi: 10.1021/ac048240a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Carlo D, Aghdam N, Lee LP. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4925–4930. doi: 10.1021/ac060541s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen F, Li X, Li PC. Biomicrofluidics. 2014;8:014109. doi: 10.1063/1.4866358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen H, Sun J, Wolvetang E, Cooper-White J. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1072–1083. doi: 10.1039/c4lc01176g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung J, Kim YJ, Yoon E. Appl Phys Lett. 2011;98:123701. doi: 10.1063/1.3565236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yesilkoy F, Ueno R, Desbiolles BX, Grisi M, Sakai Y, Kim BJ, Brugger J. Biomicrofluidics. 2016;10:014120. doi: 10.1063/1.4942457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang K, Han X, Li Y, Li SY, Zu Y, Wang Z, Qin L. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10858–10861. doi: 10.1021/ja5053279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaguchi Y, Arakawa T, Takeda N, Edagawa Y, Shoji S. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 2009;136:555–561. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin D, Deng B, Li JX, Cai W, Tu L, Chen J, Wu Q, Wang WH. Biomicrofluidics. 2015;9:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.4905428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deng Y, Zhang Y, Sun S, Wang Z, Wang M, Yu B, Czajkowsky DM, Liu B, Li Y, Wei W, Shi Q. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7499. doi: 10.1038/srep07499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Wagenaar B, Berendsen JT, Bomer JG, Olthuis W, van den Berg A, Segerink LI. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1294–1301. doi: 10.1039/c4lc01425a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung K, Kim Y, Kanodia JS, Gong E, Shvartsman SY, Lu H. Nat Methods. 2011;8:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hong S, Pan Q, Lee LP. Integr Biol (Camb) 2012;4:374–380. doi: 10.1039/c2ib00166g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hong JW, Studer V, Hang G, Anderson WF, Quake SR. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:435–439. doi: 10.1038/nbt951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ottesen EA, Hong JW, Quake SR, Leadbetter JR. Science. 2006;314:1464–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.1131370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marcy Y, Ishoey T, Lasken RS, Stockwell TB, Walenz BP, Halpern AL, Beeson KY, Goldberg SM, Quake SR. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1702–1708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fan HC, Wang J, Potanina A, Quake SR. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang J, Fan HC, Behr B, Quake SR. Cell. 2012;150:402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.White AK, Heyries KA, Doolin C, Vaninsberghe M, Hansen CL. Anal Chem. 2013;85:7182–7190. doi: 10.1021/ac400896j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Streets AM, Zhang X, Cao C, Pang Y, Wu X, Xiong L, Yang L, Fu Y, Zhao L, Tang F, Huang Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:7048–7053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi Q, Qin L, Wei W, Geng F, Fan R, Shin YS, Guo D, Hood L, Mischel PS, Heath JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:419–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110865109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toriello NM, Douglas ES, Mathies RA. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6935–6941. doi: 10.1021/ac051032d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Das CM, Becker F, Vernon S, Noshari J, Joyce C, Gascoyne PR. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2708–2719. doi: 10.1021/ac048196z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Magnus SJ, Katja U, Thomas S, Torsten M. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2008;41:175502. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas RS, Mitchell PD, Oreffo RO, Morgan H. Biomicrofluidics. 2010;4:9. doi: 10.1063/1.3406951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chrimes AF, Khoshmanesh K, Tang SY, Wood BR, Stoddart PR, Collins SS, Mitchell A, Kalantar-zadeh K. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;49:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schroder UC, Ramoji A, Glaser U, Sachse S, Leiterer C, Csaki A, Hubner U, Fritzsche W, Pfister W, Bauer M, Popp J, Neugebauer U. Anal Chem. 2013;85:10717–10724. doi: 10.1021/ac4021616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang P, Ren L, Zhang X, Shan Y, Wang Y, Ji Y, Yin H, Huang WE, Xu J, Ma B. Anal Chem. 2015;87:2282–2289. doi: 10.1021/ac503974e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen NC, Chen CH, Chen MK, Jang LS, Wang MH. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 2014;190:570–577. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xie C, Dinno MA, Li YQ. Opt Lett. 2002;27:249–251. doi: 10.1364/ol.27.000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xie CG, Li YQ, Tang W, Newton RJ. J Appl Phys. 2003;94:6138–6142. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xie C, Chen D, Li YQ. Opt Lett. 2005;30:1800–1802. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lau AY, Lee LP, Chan JW. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1116–1120. doi: 10.1039/b803598a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dochow S, Krafft C, Neugebauer U, Bocklitz T, Henkel T, Mayer G, Albert J, Popp J. Lab Chip. 2011;11:1484–1490. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00612b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chiou PY, Ohta AT, Wu MC. Nature. 2005;436:370–372. doi: 10.1038/nature03831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang KW, Wu YC, Lee JA, Chiou PY. Lab Chip. 2013;13:3721–3727. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50607j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koster S, Angile FE, Duan H, Agresti JJ, Wintner A, Schmitz C, Rowat AC, Merten CA, Pisignano D, Griffiths AD, Weitz DA. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1110–1115. doi: 10.1039/b802941e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang BL, Ghaderi A, Zhou H, Agresti J, Weitz DA, Fink GR, Stephanopoulos G. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:473–478. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu H, Caen O, Vrignon J, Zonta E, El Harrak Z, Nizard P, Baret JC, Taly V. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1366. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01454-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen F, Zhan Y, Geng T, Lian H, Xu P, Lu C. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8816–8820. doi: 10.1021/ac2022794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhan Y, Wang J, Bao N, Lu C. Anal Chem. 2009;81:2027–2031. doi: 10.1021/ac9001172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mazutis L, Gilbert J, Ung WL, Weitz DA, Griffiths AD, Heyman JA. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:870–891. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sjostrom SL, Bai Y, Huang M, Liu Z, Nielsen J, Joensson HN, Andersson Svahn H. Lab Chip. 2014;14:806–813. doi: 10.1039/c3lc51202a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zinchenko A, Devenish SR, Kintses B, Colin PY, Fischlechner M, Hollfelder F. Anal Chem. 2014;86:2526–2533. doi: 10.1021/ac403585p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brouzes E, Medkova M, Savenelli N, Marran D, Twardowski M, Hutchison JB, Rothberg JM, Link DR, Perrimon N, Samuels ML. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14195–14200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903542106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Geng T, Novak R, Mathies RA. Anal Chem. 2014;86:703–712. doi: 10.1021/ac403137h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lim SW, Tran TM, Abate AR. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0113549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leung K, Zahn H, Leaver T, Konwar KM, Hanson NW, Page AP, Lo CC, Chain PS, Hallam SJ, Hansen CL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7665–7670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106752109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fu Y, Li C, Lu S, Zhou W, Tang F, Xie XS, Huang Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11923–11928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513988112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jing T, Ramji R, Warkiani ME, Han J, Lim CT, Chen CH. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;66:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kemna EW, Schoeman RM, Wolbers F, Vermes I, Weitz DA, van den Berg A. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2881–2887. doi: 10.1039/c2lc00013j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chabert M, Viovy JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3191–3196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Edd JF, Di Carlo D, Humphry KJ, Koster S, Irimia D, Weitz DA, Toner M. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1262–1264. doi: 10.1039/b805456h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cao Z, Chen F, Bao N, He H, Xu P, Jana S, Jung S, Lian H, Lu C. Lab Chip. 2013;13:171–178. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40950j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu L, Chen P, Dong Y, Feng X, Liu BF. Biomed Microdevices. 2013;15:553–560. doi: 10.1007/s10544-013-9754-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang Q, Wang T, Zhou Q, Zhang P, Gong Y, Gou H, Xu J, Ma B. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41192. doi: 10.1038/srep41192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu C, Liu J, Gao D, Ding M, Lin JM. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9418–9424. doi: 10.1021/ac102094r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chin VI, Taupin P, Sanga S, Scheel J, Gage FH, Bhatia SN. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88:399–415. doi: 10.1002/bit.20254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tokimitsu Y, Kishi H, Kondo S, Honda R, Tajiri K, Motoki K, Ozawa T, Kadowaki S, Obata T, Fujiki S, Tateno C, Takaishi H, Chayama K, Yoshizato K, Tamiya E, Sugiyama T, Muraguchi A. Cytometry A. 2007;71:1003–1010. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Guo P, Hall EW, Schirhagl R, Mukaibo H, Martin CR, Zare RN. Lab Chip. 2012;12:558–561. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21092d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bocchi M, Rambelli L, Faenza A, Giulianelli L, Pecorari N, Duqi E, Gallois JC, Guerrieri R. Lab Chip. 2012;12:3168–3176. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40124j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Faenza A, Bocchi M, Duqi E, Giulianelli L, Pecorari N, Rambelli L, Guerrieri R. Anal Chem. 2013;85:3446–3453. doi: 10.1021/ac400230d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Huang L, Chen Y, Chen Y, Wu H. Anal Chem. 2015;87:12169–12176. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]