Abstract

Diagnosing autoimmune encephalitis (AE) is complicated by several factors, including issues with availability, sensitivity, and specificity of antibody testing, particularly with variability in assay techniques and new antibodies being rapidly identified; nonspecific findings on MRI, EEG, and lumbar puncture; and competing differential diagnoses. Through case-based discussions with 3 experts from 3 continents, this article discusses the challenges of AE diagnosis, important clinical characteristics of AE, preferences for methods of autoantibody testing and interpretation, and treatment-related questions. In particular, we explore the following question: If a patient's clinical presentation seems consistent with AE but antibody testing is negative, can one still diagnose the patient with AE? Furthermore, what factors does one consider when making this determination, and should treatment proceed independent of antibody testing in suspected cases? The same case-based questions were posed to the rest of our readership in an online survey, the results of which are also presented.

Autoimmune encephalitis (AE) is a form of noninfectious neuroinflammation that has become an increasingly recognized cause of acute/subacute progressive mental status change with a variety of clinical phenotypes. Some cases of AE are associated with specific autoantibodies to a number of structures, including cell surface molecules as well as intracellular targets.1 However, it is common for antibody testing to return negative, in which case clinicians must make a diagnosis based on a combination of clinical phenotypes, CSF results, and neuroimaging. While some cases of suspected AE might respond positively to immunotherapy, this outcome is neither consistent nor specific.

A recently published position paper suggested a clinically grounded guideline for diagnosis of AE.2 The reason for this is twofold: antibody testing is not always available at many institutions, and results of antibody testing, positive or negative, are not perfectly sensitive or specific. The practical challenge of diagnosing AE and interpreting test results is complicated by the fact that new antibodies are being identified at a rapid pace,3,4 and known antibodies have been identified in clinically less suspicious cases such as an isolated first presentation of psychosis.5 In addition, the sensitivity and specificity of a given antibody test will depend on the type of assay performed by the laboratory. Available techniques include indirect tissue immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry, which serve as excellent screening tools for the presence of neural antibodies; Western blot, which is best suited for detecting antibodies binding to cytosolic or nuclear antigens; radioimmunoprecipitation assays, useful for detecting ion channel antibodies; and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), widely available and rapid but limited by false-positive results from binding to the plastic well of the ELISA plate.6 Cell-based assays—in which the target antigen is natively expressed in mammalian cells on a microscopy slide, and binding of the antibody of interest is detected using an antihuman secondary antibody—offer improved specificity over these other techniques, though they typically require a trained evaluator and may not be as readily available.6 Further clouding the picture, in many patients, antibody-mediated CNS syndromes may not be associated with any evidence of inflammation in MRI and CSF studies.7 There are also a number of differential diagnoses to consider with AE-like presentations (table e-1, links.lww.com/CPJ/A10).2,8

In this regard, we sought to explore the following question: If the clinical presentation seems consistent with AE but antibody testing is negative, can one still diagnose the patient with AE? Furthermore, what factors does one consider when making this determination, and should treatment proceed independent of antibody testing in suspected cases? Given a number of uncertainties, and a paucity of high-quality data in the literature, we sought expert opinion from around the globe on these timely questions.

Expert opinion

Questions were posed to experts from 3 different continents, representing differing medical systems and patient populations. The following summary of their responses addresses the challenges of AE diagnosis, important clinical characteristics of AE, preferences for methods of autoantibody testing and interpretation, and treatment-related questions. We also asked each expert to discuss their approach to 2 representative cases potentially suspicious for AE (appendix e-1, links.lww.com/CPJ/A11 for cases and multiple-choice questions). These same cases and questions were posed to the rest of our readership in an online survey, the results of which are presented following the expert commentaries.

In alphabetical order:

Jeffrey Gelfand, MD (United States)

Approach to suspecting and investigating AE

Criteria have been proposed to help identify and diagnose clinical presentations of AE (both antibody-positive and antibody-negative AE), and can be a helpful reference for clinicians.2 AE has a differential diagnosis, and it is critical to evaluate for both infectious and autoimmune causes (of which some may be paraneoplastic). In suspected AE cases, I generally prefer to send both serum and CSF for antibody testing. Test characteristics are currently such that some antibodies are more sensitive when testing serum (e.g., LGI1) whereas others are more sensitive when testing CSF (e.g., NMDAR). Antibody panels are generally preferable given that the clinical phenotypes of these syndromes overlap; there is also the potential for more than one antibody to be present. As with all diagnostic tests, it is important to interpret autoantibody testing in clinical context. In other words, antibody testing alone does not make a diagnosis. It is also important to recognize that AE can be “antibody-negative.” Antibody-negative autoimmune encephalitis may occur due to (1) insensitivity of currently available clinical antibody testing (and sensitivity will depend greatly on assay specifics, including whether it is cell-based or incorporates screening of serum or CSF against rodent brain slices); (2) presence of novel or newly discovered neuronal or glial autoantibodies not yet available via clinical laboratory testing; or (3) CNS inflammation that may not be antibody-mediated or associated. Evaluation of CSF or serum for novel or newly characterized antibodies by a research laboratory experienced in AE may be informative in such cases.

Approach to treatment

Once other differential diagnoses have been adequately addressed based on additional clinical history (including exposure and travel history), comprehensive physical examination, and case-specific infectious disease diagnostics taking into account local epidemiologic factors, for clinically suspected AE cases I would start empiric acute immunosuppressive therapy with glucocorticoids with early additional consideration of IV immunoglobulin G (IVIg) or plasma exchange (PLEX) while awaiting the results of confirmatory AE autoantibody testing. Rigorous exclusion of other potential causes is a key diagnostic criterion for both antibody-positive and antibody-negative AE, and this should include careful monitoring and clinical re-evaluation particularly when empiric immunosuppression is initiated. If the diagnosis remains most consistent with antibody-negative AE, I would then continue down the pathway of further empiric immunosuppressive therapy, weighing case-specific factors to select among the many other available immunosuppressive treatment options.

Case discussion

Regarding case 1, given the neuropsychiatric syndrome, brain MRI findings consistent with encephalitis, and the lymphocytic pleocytosis on CSF examination, the clinical syndrome is consistent with a limbic encephalitis. Given the patient's age and clinical phenotype, the most likely autoimmune cause would be NMDAR antibody encephalitis. A targeted search for malignancy should also be initiated, at the very least an ultrasound or pelvic MRI to evaluate for ovarian teratoma given clinical suspicion for NMDAR encephalitis; CT or MRI of the chest/abdomen/pelvis and whole body FDG-PET would also be important to consider as a next step, particularly if NMDAR antibodies are negative. For case 2, new-onset localization-related seizures of this kind has a broad differential diagnosis, and an autoimmune cause would be one important consideration. A CSF examination is needed, and I would send both serum and CSF autoantibodies in addition to CSF cell counts, chemistries, oligoclonal bands, immunoglobulin G index, and a targeted infectious workup as informed by the initial results, case specifics, and local epidemiology. In particular for case 2, I would prefer to have more diagnostic information and diagnostic detail to support a working diagnosis of autoimmune epilepsy as a manifestation of AE. If after additional diagnostics (CSF examination, MRI review) the clinical syndrome is most consistent with an AE, whether antibody-negative or -positive, and after rigorous exclusion of other causes including CNS infection, malignancy, and other causes of seizure, then empiric acute immunosuppressive therapy pending neuronal autoantibody results would be appropriate. Observational data indicate that seizures from AE—and autoimmune epilepsy syndromes associated with neuronal autoantibodies—can have favorable treatment responses with immunosuppression even when refractory to conventional antiseizure medication. I would treat with acute immunosuppressive therapy.

Sarosh R. Irani, DPhil, MRCP (Neurol) (United Kingdom)

Approach to suspecting and investigating AE

I am guided by a combination of timing of onset and clinical features. The timing of onset is often subacute, a few days to a few weeks (usually 3 months or less), but it is important not to be too strict about this. Some patients can have a genuinely acute overnight presentation, while some can have an insidious progression of symptoms over several months, almost like some cases of Alzheimer disease. As for clinical features, I look for multiple neurologic or neuropsychiatric symptoms. Very few patients have a pure cognitive syndrome; usually there is also a movement disorder, seizures, or sleep disturbances. Others may just have seizures but these are generally atypical in some way, often very frequent or associated with subtle neuropsychiatric features. It is important not to discriminate on the basis of age, sex, or prior autoimmune or psychiatric history, as these do not appear to be reliable in favoring or arguing against an AE diagnosis. In suspected AE cases, the key investigations that I pursue quickly are lumbar puncture, MRI, and EEG. Importantly, these can all be normal, although in an encephalitic presentation, you often expect more than 5 cells in the CSF. EEG is reasonably sensitive but not specific. Slowing of any kind on EEG is helpful, and we can see delta brush in some NMDA encephalitis cases. Epileptiform activity can be helpful, but really what I am looking for is an absence of EEG findings; particularly in very psychiatric presentations, a normal EEG can help reassure us that there is not underlying AE. There are sometimes helpful clues in the bloodwork, like low serum sodium in LGI1 encephalitis. Whenever possible, I will obtain antibody testing in both serum and CSF. With NMDA encephalitis, it is clear that a positive result in the CSF has high predictive value; one the other hand, CSF antibody testing is not always positive in LGI1 or Caspr2 encephalitis.

Approach to treatment

I do not wait for antibody results to treat patients; ultimately I am still going to end up relying on clinical presentation more than any test results. We have been treating many patients with suspected AE purely on the basis of clinical suspicion. For example, I recently treated a man with new onset of very frequent focal seizures who progressed to encephalopathy over a few days. There was very little in the way of a differential diagnosis once we had a normal structural brain scan. In such cases, we can feel safe to treat these patients, as acute treatment with short courses of steroids is unlikely to cause significant harm. I use IV steroid pulses as first-line treatment. I often use PLEX along with steroids. For second-line treatment, I increasingly prefer PLEX over IVIg; although any data available suggest equivalence, I find that PLEX has greater efficacy. With PLEX, we often find that CSF antibody levels drop surprisingly quickly. IVIg does not require as much sedation, but in centers like Oxford we are able to perform PLEX without using a central line, with a lower risk of infection. Negative antibody test results should always make you reconsider the diagnosis, but it is rare that this ends up changing your clinical approach as the clinical presentations are so distinctive and the common differential diagnoses are so easily excluded (such as with CSF viral PCR for viral encephalitis). We can assume it is AE after excluding other diagnoses. We have had only one patient in whom we have revised the diagnosis.

Case discussion

Case 1 is a presentation consistent with AE. I would send off antibody tests in both the serum and CSF, but I would not wait for the results to come back to initiate treatment with IV steroids. A negative panel would not change my decision to treat. As long as other investigations were reassuring, there is little else in the way of a differential diagnosis here; a negative panel is not very unusual. If the patient has not shown a response within a couple of weeks, I would pursue PLEX if I had not already done so. If the disease course behaves like AE, then we could carry on with treatment and wait (perhaps the patient will turn a corner later), or we could also give IVIg. If there is an inadequate response to all these treatments, then we consider other immune-suppressing agents like cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil titrated up quickly. In the United Kingdom, we are unable to give rituximab for this indication. It is also reasonable to reimage the brain to see if there is an evolving brain lesion like a tumor; reimaging the body within just a few weeks is less helpful. Similarly, in case 2, I would also send antibody tests in both the serum and CSF. If the scan had been normal, then it may have been reasonable to hold off on treating the patient, but with an abnormal scan consistent with AE, then I would treat with immunotherapy without waiting for the antibody results.

Chandrashekhar Meshram, MD, DM (India)

Approach to suspecting and investigating AE

AE is a relatively new and emerging area of neurologic disease, so if we as neurologists do not suspect it, the patients will not be diagnosed. I suspect the possibility of AE in all patients who present with an evolution of symptoms that could be in keeping with the disease. This often includes a viral infection-like prodromal history—fever, malaise, headache, or anorexia—often followed by psychiatric symptoms like anxiety, depression, hallucinations, sleep disturbance, and psychosis, and then short-term memory impairment, temporal lobe type seizures, or autonomic dysfunction, encephalopathy, or coma. So if I have a young patient with these types of clinical manifestations, my approach is to obtain an MRI brain, EEG, and CSF analysis mainly to rule out other causes (particularly viral or other infections, toxic or metabolic etiologies, and underlying malignancies). The MRI might show predominant medial temporal lobe involvement but I find that it is normal in the majority of cases, and the EEG too can be nonspecific, though some patients with NMDA encephalitis can demonstrate extreme delta brush. CSF can show a mild protein rise and pleocytosis, usually <100 cells. I send off autoimmune antibody tests in both the CSF and serum in these patients.

Approach to treatment

I do not wait for antibody results—there are new antibodies being implicated all the time and the ones we test for may come back negative. If no other cause is found, then even with negative antibody results I would treat. So if I suspect AE, I start treatment with immunomodulatory treatment right away if CSF analysis indicates that an infection is unlikely, starting with IV methylprednisolone (IVMP) 1 g daily for 5 days. If the patients can afford the treatment, I give them IVIg and IVMP simultaneously. If no response is seen within a couple of weeks, then I turn to rituximab as a second-line agent; however, if the symptoms are particularly severe, then I give all 3 agents simultaneously.

Lower/middle-income country challenges

As for issues with AE management in lower/middle-income country settings, one of the main challenges in India is the deficiency of neurologists. We have more than 1.3 billion people and only 1,800 neurologists. Consequently, most of the patients are managed by internists, but many of them are also referred to psychiatrists. The majority of patients and doctors are unaware of AE, so there is often a delay in diagnosis. The most common alternative diagnosis provided is viral encephalitis (given preceding fever or malaise), but psychiatrists can often attribute subsequent neurologic symptoms to side effects of antipsychotics used to treat psychiatric symptoms. Unless we adopt a team approach and work with these colleagues, we cannot achieve timely diagnosis and treatment. The majority of patients do not reach neurologists in time, and this delay can result in poor outcomes. In addition, the majority of antibody tests for AE are not easily available; when they are offered commercially, they cost about $350, which many patients cannot afford (although government hospitals provide free-of-cost health care facilities, in practice, Indian patients are often served in the private health care sector with expenses paid out of pocket rather than through private insurance, contributing to a high financial burden for families).9 Clinical judgment therefore becomes very important. With respect to treatment options, again, affordability becomes an issue. Many patients are not covered by health insurance and cannot afford IVIg and steroid treatment. PLEX is not easily available, and even IVIg is not available in many government hospitals.

Case discussion

Case 1 highly favors a diagnosis of AE. I would not wait for antibody results to treat this patient. I would continue immunotherapy even if there is not a noticeable response; sometimes it takes up to 4 weeks for these patients to show a response. If this patient still is not showing a response at that point, then I would use steroids along with PLEX/IVIg. If IVIg had already been used with steroids, then I would add rituximab. Sometimes underlying malignancies like ovarian teratomas may be missed on initial scans and could aggravate the patient's AE; I would consider a PET scan and would follow this patient closely, every 6 months. As for case 2, I would send antibodies in both the serum and the CSF. I find that serum can give false results. In this case as well, I would start treatment without waiting for antibody results.

Preliminary survey results (December 12, 2017): Section Editor Luca Bartolini, MD

We collected a total of 463 complete individual questionnaires over the course of 2 weeks. The majority of survey takers practice outside of the United States (84%) and see adults only (85%). Only a minority (14%) identify themselves as neuroimmunologists. Most represented countries are United States (n = 75), India (n = 38), Spain (n = 36), Italy (n = 33), and Brazil (n = 27). About half of responders are faculty, while 39% are trainees and a growing 8% are advanced care providers. Most neurologists (65%) stated they had seen between 1 and 5 patients with AE over the last 12 months.

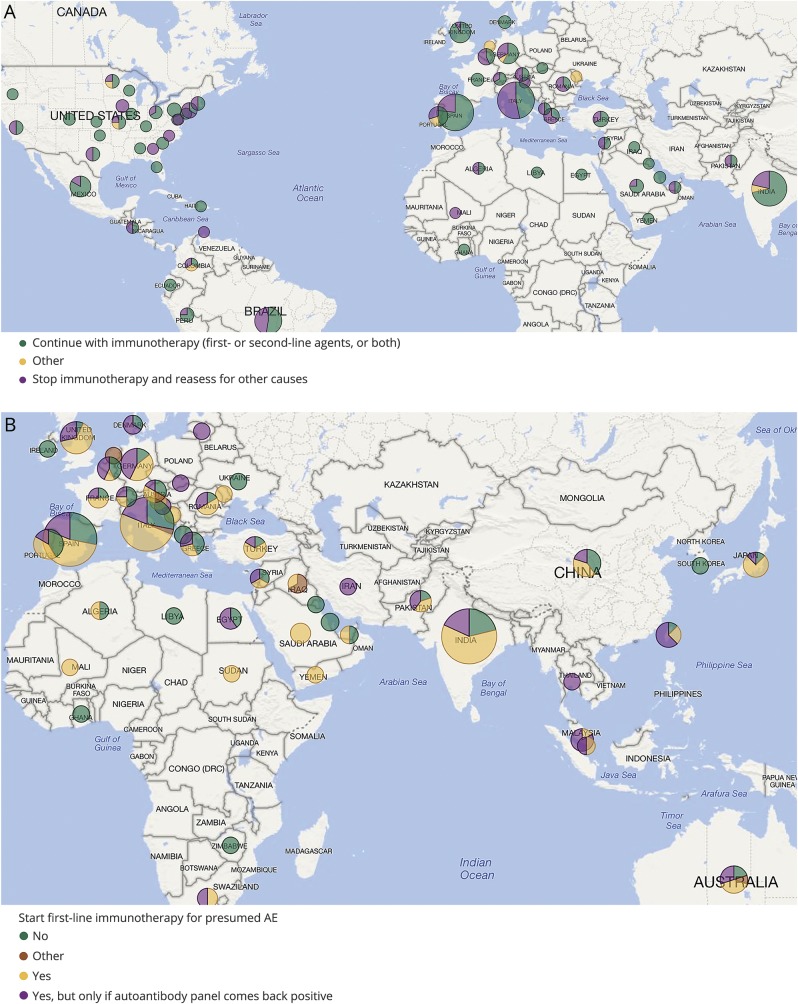

For the first case about a young adult woman who presents with acute psychiatric symptoms and is found to have mild CSF pleocytosis and MRI T2 hyperintensity in the medial temporal lobes, almost all responders (94%) agree to send an autoimmune antibody panel in both serum and CSF (93%). Similarly, 87% would start empiric treatment for presumed AE, with results of the antibody panel still pending. Interestingly, when asked what they would do if after 2 weeks from initial therapy the patient had made no substantial improvement and antibody panel came back negative, 36% would stop immunotherapy (figure, A).

Figure. Interactive world map.

(A) Responses to the question on continuation of therapy in case of high clinical suspicion for autoimmune encephalitis (AE) but lack of improvement after 2 weeks from initial immunotherapy and negative antibody testing, showing that 36% of responders would stop immunotherapy. (B) Decisions to start immunotherapy around the globe in a patient with new onset temporal lobe seizures and short-term memory loss, revealing overall lack of consensus. The size of the pie charts is proportional to the total number of responses from a specific country or state.

For the second case about an adult with new onset temporal lobe seizures and short-term memory impairment, the majority of responders chose to send an autoimmune antibody panel in both serum and CSF (70%) at presentation. Forty-three percent also recommended starting empiric first-line immunotherapy, while 25% chose to do it only if the autoimmune panel came back positive, and 29% decided not to use immunotherapy (figure, B). For those who decided to wait, a low-titer positive anti-NMDAR antibody result and persistence of focal seizures would prompt them to initiate immunomodulation.

After analyzing these results, it is inevitable to ask what the threshold should be to send an autoimmune panel and to use immunotherapy in patients with new onset imaging-negative temporal lobe epilepsy. Should this approach be reserved for those patients who have additional concerning features, such as, for example, memory impairment or psychiatric manifestations, or should all patients at least be tested? It is conceivable that the underlying process that leads to seizure generation, if autoimmune in nature, would take time to develop; also, temporal lobe seizures can be subtle, so it may be difficult to pinpoint the exact time of seizure onset in a patient's life. All things considered, would it be reasonable to have more evidence and wait 2 more weeks for a positive antibody panel before starting medications with potentially serious side effects, or should this decision not be influenced by the results of this test?

Discussion

To the practicing neurologist, the diagnostic process for AE can seem fraught with uncertainty, with typical investigations like neuroimaging, EEG, and CSF testing often being unremarkable, new antibodies constantly on the horizon, and high-quality diagnostic and treatment studies difficult to come by. Nevertheless, the remarkably consistent responses of our 3 experts, particularly with respect to the cases posed, can provide a measure of reassurance. Despite their different practice settings, all of them agreed that the diagnosis of AE should be driven primarily by the patient's clinical presentation and the exclusion of key differential diagnoses, particularly infectious etiologies, and that workup should involve a thorough search for associated malignancies. While they differed in their preferences for immunotherapy, all 3 emphasized the importance of treating suspected cases of AE with at least steroids while awaiting the results of antibody testing. They also agreed that antibody testing for AE should be performed on both CSF and serum samples, but cautioned against overreliance on these test results. In particular, negative test results for known or available antibodies would not dissuade them from treating patients with presentations that are otherwise clinically convincing for AE. Fortunately, even in the rapidly evolving era of antibody-mediated syndromes, it would seem that bedside assessment and clinical judgment remain paramount.

Biography

Jeffrey Gelfand, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). He specializes in caring for patients with a wide range of neuroinflammatory disorders, conducts clinical research, and is an award-winning medical educator. Dr. Gelfand received an AB in history from Princeton University, graduating summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa. He received his MD from Harvard Medical School. He completed an internship in internal medicine, residency in neurology, and fellowship training in MS/neuroimmunology, all at UCSF, and is board-certified in neurology. Dr. Gelfand received a Masters in Advanced Study (MAS) in Clinical Research at UCSF. His research focuses on advancing care for people with autoimmune encephalitis, multiple sclerosis, neurosarcoidosis, and other neuroinflammatory conditions. Dr. Gelfand directs the UCSF MS and Neuroinflammation Center Fellowship Program. He is a recipient of the Robert B. Layzer teaching award, which is voted on annually by UCSF Neurology Department residents, and an Excellence in Teaching Award from the UCSF Haile T. Debas Academy of Medical Educators. Dr. Gelfand was elected as a Fellow of the American Academy of Neurology (FAAN), serves as a member of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Clinical Research Subcommittee, and cofounded the AAN Autoimmune Neurology section.

Sarosh R. Irani, DPhil, MRCP (Neurol), is an Associate Professor and consultant neurologist who heads the Oxford Autoimmune Neurology Group research laboratory. Dr. Irani has clinical and laboratory experience in the field of autoantibody-mediated diseases of the nervous system, in particular the CNS. He cares for patients with these disorders and runs a research group to learn more about the origins and treatments of these diseases. His group has patented the discovery of LGI1 and CASPR2 antibodies, and described faciobrachial dystonic seizures as a highly distinctive clinical feature associated exclusively with LGI1 antibodies. Their recent work shows that early treatment of this syndrome with immunotherapy appears to prevent onset of cognitive impairment associated with encephalitis. His group works to make pathophysiologic sense of these phenotype–antibody correlations by studying neuronal models of the effects of antibodies, and by understanding the mechanisms by which the antibodies are generated. In particular, they are interested in obtaining immune cells that make autoantibodies from patients with aquaporin-4 NMDA-receptor antibodies, and assessing conditions that promote and inhibit antibody production. They anticipate this will provide insights into the mechanisms by which autoantibody production can be inhibited.

Chandrashekhar Meshram, MD (Medicine), DM (Neurology), is a consultant neurologist and Director, Brain and Mind Institute, Nagpur, India. He is President of the Tropical and Geographical Research Group of the World Federation of Neurology (WFN). He served the Indian Academy of Neurology (IAN) for 11 years as President, Secretary, and Executive Committee Member. The IAN conferred on him the title of Fellow of the IAN (FIAN) in 2012. Dr. Meshram was organizing secretary of the 12th Annual Conference of the Indian Academy of Neurology in 2004 in Nagpur and the International Tropical Neurology Conference in Mumbai in 2017. He served for 3 years as the first Editor-in-Chief of Indian Clinical Updates Neurology published by Wiley Blackwell. He has 30 publications to his credit in national and international journals and has been the principal investigator for 18 multicenter clinical trials. Dr. Meshram has represented India 6 times as National Delegate for the Council of Delegates meetings of WFN. He was a member of the constitution and by-laws committee of WFN for 4 years. He is now a member of the Scientific Program Committee of WFN. For the last 3 years, he has helmed the National Brain Week campaign for public education and awareness of neurologic disorders by IAN.

Footnotes

Explore this topic: NPub.org/NCP/pc6

Interactive world map: NPub.org/NCP/map06

More Practice Current: NPub.org/NCP/practicecurrent

Author contributions

A. Ganesh and S. Wesley were involved in the conception, writing, and revising of the article, as well as interviewing of expert opinion contributors.

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

A. Ganesh is a member of the editorial staff of the Resident & Fellow Section of Neurology®; has received speaker honoraria and/or funding for travel from The Meritas Seminar Series, Oxford; University of Calgary Post-Graduate Medical Education, St John's College, Oxford; and International Stroke Conference; has served as a consultant for Adkins Research Group and Genome BC; receives research support from The Rhodes Trust and Wellcome Trust; and holds stock/stock options from SnapDx, TheRounds.ca, and Advanced Health Analytics (AHA Health Ltd). S. Wesley is a member of the editorial staff of the Resident & Fellow Section of Neurology. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Dalmau J, Geis C, Graus F. Autoantibodies to synaptic receptors and neuronal cell surface proteins in autoimmune diseases of the central nervous system. Physiol Rev 2017;97:839–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:391–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gresa-Arribas N, Planaguma J, Petit-Pedrol M, et al. Human neurexin-3alpha antibodies associate with encephalitis and alter synapse development. Neurology 2016;86:2235–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabater L, Gaig C, Gelpi E, et al. A novel non-rapid-eye movement and rapid-eye-movement parasomnia with sleep breathing disorder associated with antibodies to iglon5: a case series, characterisation of the antigen, and post-mortem study. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:575–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayser MS, Titulaer MJ, Gresa-Arribas N, Dalmau J. Frequency and characteristics of isolated psychiatric episodes in anti-n-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:1133–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters P, Pettingill P, Lang B. Detection methods for neural autoantibodies. Handb Clin Neurol 2016;133:147–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escudero D, Guasp M, Arino H, et al. Antibody-associated CNS syndromes without signs of inflammation in the elderly. Neurology 2017;89:1471–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lancaster E. The diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune encephalitis. J Clin Neurol 2016;12:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman P, Ahuja R, Bhandari L. The impoverishing effect of healthcare payments in India: new methodology and findings. Econ Polit Weekly 2010;45:65–71. [Google Scholar]