Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: left ventricular assist devices, infection, 18F-FDG PET/CT

Abstract

Implantable continuous flow left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are increasingly used in end-stage heart failure treatment as a bridge-to-transplant and destination therapy (DT). However, LVADs still have major drawbacks, such as infections that can cause morbidity and mortality. Unfortunately, appropriate diagnosis of LVAD-related and LVAD-specific infections can be very cumbersome. The differentiation between deep and superficial infections is crucial in clinical decision-making. Despite a decade of experience in using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) to diagnose various infections, its use in LVAD patients remains scarce. In this case series, we review the current evidence in literature and describe our single center experience using 18F-FDG PET/CT for the diagnosis and management of LVAD infections.

Continuous flow left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are increasingly used as bridge-to-transplantation or destination therapy (DT).1 However, driveline and pump infections remain a major point of concern, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. The consequences of a LVAD infection depend on the location, depth, and the severity of the infection. There is currently no gold standard test available for the detection of the exact site of infection or to monitor the response to treatment of LVAD infections.2

The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) has proposed standard criteria for the clinical, microbiologic, and radiologic diagnosis of infection in LVAD patients.2 These definitions allow for comparative analysis of time course, incidence, outcome, and risk factors for infection in ventricular assist device (VAD) recipients.

However, data regarding the optimal imaging technique to detect infection and monitor the response to treatment in these patients is lacking. In this regard, ultrasound imaging and computed tomography (CT) angiography can be helpful in detecting fluid collections around drivelines, cannulas, and pump. Historically, nuclear imaging modalities described in case series about LVAD infections, are 99mTc-leucocyte and 67 Gallium scintigraphy.3,4 However, nowadays 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) is increasingly used in the diagnostic work-up of infectious endocarditis, especially in the detection of metastatic and primary extra-cardiac infections.5 Despite a decade of experience in using 18F-FDG PET/CT to diagnose various infections, its use in LVAD remains scarce.6–8

In this case series, we describe our single center experience using 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of LVAD infections. Additionally, we have conducted a literature review on LVAD-related and -specific infections and the use of diagnostic nuclear imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT scans.

Methods

Patients

All consecutive HeartMate II (HMII) implantations performed between January 2011 (PET-CT camera installed in the hospital) and May 2016 in our tertiary referral center were reviewed. These data were extracted from the ongoing EuroMacs Registry (European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support) database.9 Patients have agreed with the registry and signed the informed consent. The patients who had 18F-FDG PET/CT scintigraphy to investigate suspected LVAD-related or LVAD-specific infections were included in this case series. Their clinical courses were reviewed, including medical history, comorbidities, microbiologic and laboratory investigation, and imaging results (Table 1). We categorized these patients into three groups based on their clinical, microbiologic, and nuclear imaging characteristics: 1) persistent LVAD-specific infection with positive blood cultures, 2) persistent LVAD-specific infection with negative blood cultures, and 3) fever of unknown origin with negative blood cultures and swab.

Table 1.

Overview of All Patients with a LVAD Needing 18F-FDG PET/CTs in the Correct Localization of Infections. Clinical, Microbiologic, and Nuclear Imaging Characteristics

18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging

All 18F-FDG PET/CT images were acquired using a Siemens Biograph mCT (Siemens Medical Solutions USA Inc., Malvern, PA). Data were iteratively reconstructed (3 iterations, 21 subsets, and 5 mm Gaussian filter) using time-of-flight information and resolution recovery. Low-dose CT was used for attenuation correction. The protocol of patient preparation and scanning was according to the guidelines of Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). As we were interested in imaging of infection near the myocardium, it was important to avoid physiologic uptake of glucose by normal myocardium cells. Therefore a low carbohydrate diet for 24 h before the PET/CT study was recommended to switch the myocardium from using glucose as an energy source to using fatty acids, this is one of the options to reduce physiologic myocardial uptake as suggested in the mentioned guidelines.10,11 In short, patients had a low carbohydrate diet 1 day before the regular fast of 6 h. A total of 2.3 MBq/kg body weight 18F-FDG was administered after which patients were resting in a quiet and warm waiting room (to avoid uptake in muscles, brown fat, etc.). Imaging started 60 min after administration. Low-dose CT was directly followed by PET imaging: the latter for 3 min/bed position for patients <70 kg and for 4 min/bed position for patients >70 kg. This meant total imaging time of about 30 min for scintigraphy from skull to groin. Interpretation of scans was performed on both for attenuation corrected and noncorrected images to avoid false positive judgment caused by artifacts introduced by attenuation correction.

Literature Search

Additionally, we performed a PubMed/Medline search by using MeSH terms focusing on articles on LVAD-related and LVAD-specific infections and on use of diagnostic nuclear imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT scans. Basic information collected included journal, author, year published, number of patients, and types of LVAD. Specific data collected included the clinical problem, method(s) of (nuclear) imaging, and outcome.

Results

Fifty-one HMII implantations were performed in 48 patients between January 2011 and May 2016. In 9 patients (7 males; mean age 54 ± 15 years) with suspected LVAD-related infections, a total of 10 18F-FDG PET/CTs were performed. The primary indications for LVAD implantation were bridge-to-transplant (8/9) and DT (1/9).

The median duration of LVAD support from implantation or exchange to 18F-FDG PET/CT was 134 days (range 24–645 days). The long-term mortality rate was 11%. A (semi-)urgent listing for heart transplantation (HTx) caused by infectious complications was needed in 4 patients (44%), after a median of 59 days (range 49–200) after the first PET/CT. The detailed clinical characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table 1.

Overall, we describe 9 patients with suspected LVAD infection, either pump or driveline; in 33% blood cultures were positive and in 44% wound cultures were positive. 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed to establish and determine the extent of LVAD-related or -specific infections. In 3 patients we performed the 18F-FDG PET/CT within 90 days postoperative (= short-term) and in 6 patients the 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed at longer term follow-up. Sixty-seven percent of the patients had unexpected extensive deep infections. In 2/9 patients, 18F-FDG PET/CT was able to rule out any LVAD-related or -specific infections, both very early (24 and 29 days, respectively) in the postoperative phase. In only one patient there was an isolated pump inflow cannula infection (see Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/ASAIO/A138).

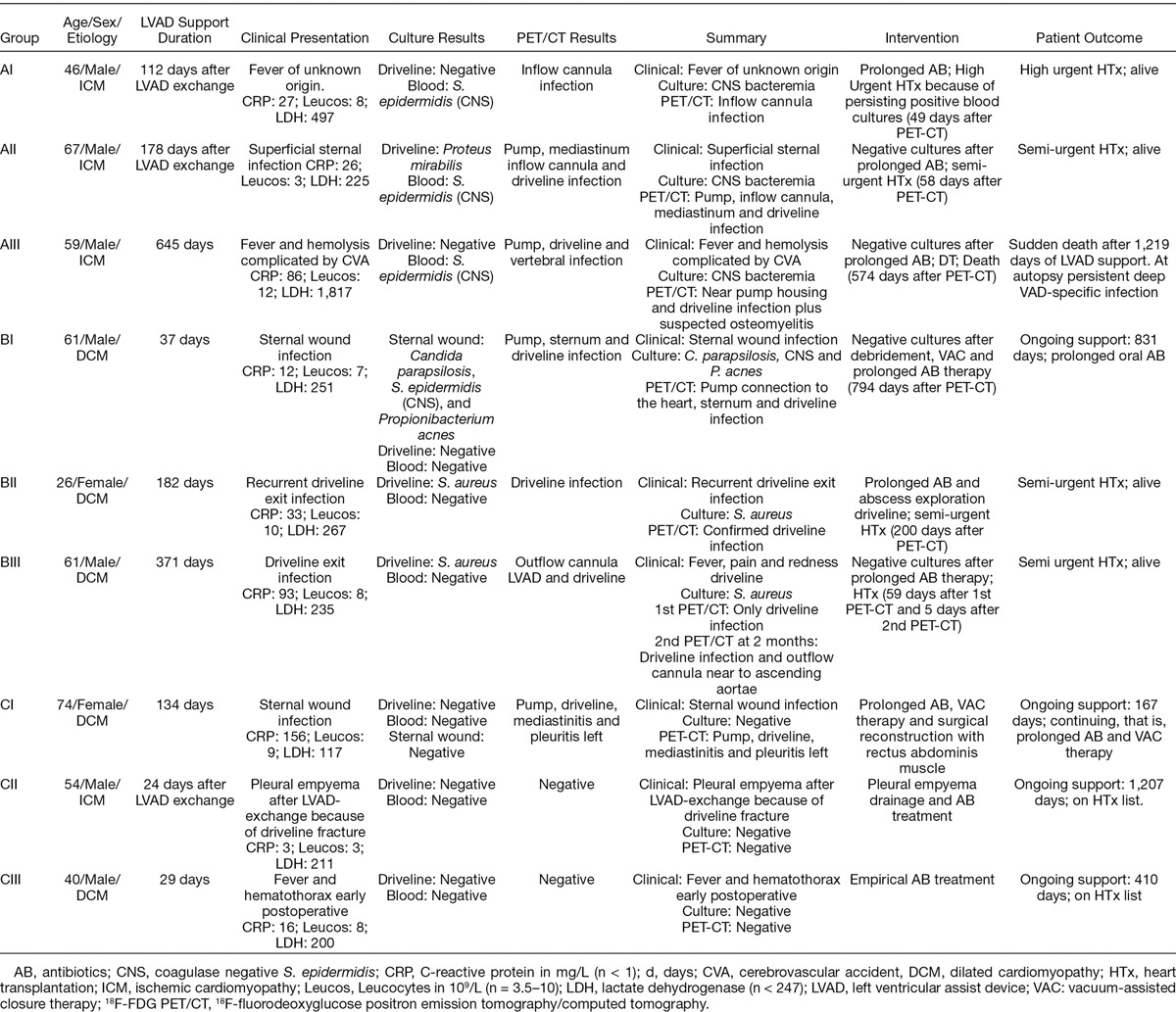

A. Persistent LVAD-specific infection with positive blood cultures: This type of infection was observed in 3 patients (see Table 1; cases AI–AIII), in which 18F-FDG PET/CT scans were performed because of recurrent positive blood cultures despite antibiotics (AB) therapy for 3–6 weeks. In case I (AI in Table 1), the connection between the inflow cannula and the pump body was detected as the source of LVAD infection (Figure 1A). Unfortunately, replacing the LVAD would have been a very high risk operation because of a previous LVAD replacement caused by driveline fracture. The patient was placed on the high urgency list for HTx, and was transplanted 49 days later under AB treatment. After explantation of the LVAD, debris was found in the connection between inflow cannula and the pump housing (Figure 1B). Microscopy showed the same monoculture of Staphylococcus epidermidis as in patient’s previous cultures. The patient is currently doing well and has not experienced any severe infections 3 years after HTx.

Figure 1.

A: Case AI: 18F-FDG PET/CT images of a high FDG ring around the inflow cannula of the LVAD. Banded ring with high degree of accumulation in the connection part of the inflow cannula with the housing. B: Case AI: Picture of the debris we found in the connection between inflow cannula and pump housing (hands of Dr. A.P.W.M. Maat). 18F-FDG PET/CT, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography; LVAD, left ventricular assist devices.

In case AII, this 67 year old male LVAD patient was admitted 175 days after LVAD exchange by sternal infection with coagulase negative Staphylococcus epidermidis (CNS) bacteremia. Ongoing deep infection despite AB therapy proved by 18F-FDG PET/CT led to semi-urgent HTx. The interval after LVAD removal and HTx was complicated by infection, and bacteremia with Enterobacter aerogenes detected in fluid aspirated from the substernal region and in the explanted driveline. A reoperation to address a possible mediastinitis was considered and planned. At day 17 post-HTx, a newly performed 18F-FDG PET/CT showed a hot spot just caudal to the sternum, which was a nonencapsulated fluid collection from which the same Enterobacter species was cultured after an ultrasound-guided puncture. The former driveline route was no longer considered as infected and the planned operation for a mediastinitis was cancelled. The patient has had no infectious problems at 31 months of follow-up periode (FUP) post-HTx.

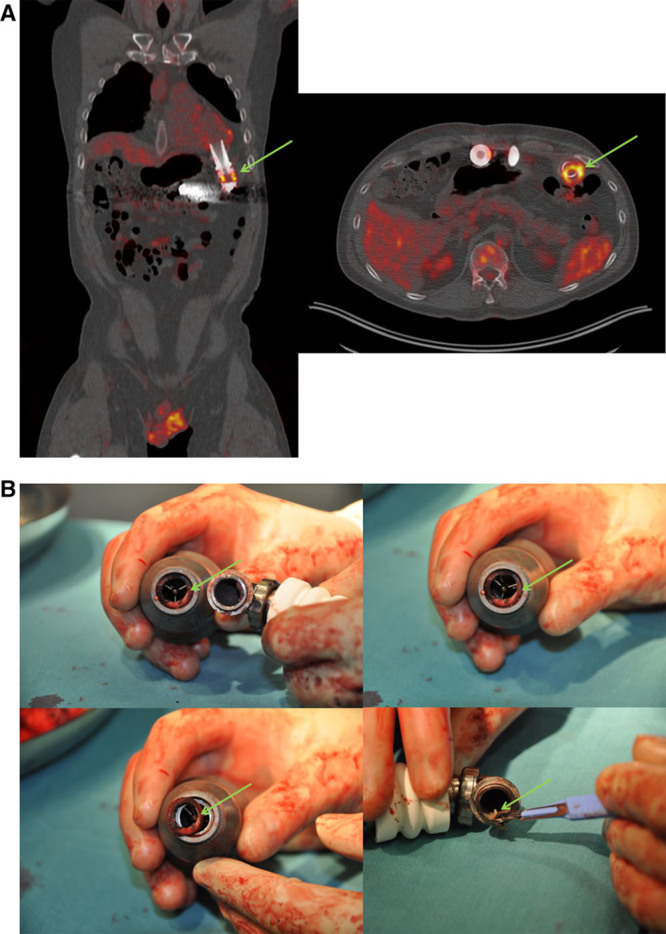

In one patient (case AIII; Figure 2), osteomyelitis was detected at the level of the 5th lumbar vertebra (L5), in addition to a LVAD and driveline infection. Unfortunately, because of severe infection, he became a DT patient and died after acute LVAD failure 1,219 days after implantation. Large bacterial growths were found at the insertion opening of the driveline, and around the LVAD on autopsy. The treatment of the rest of this group of patients varied according to the 18F-FDG PET/CT findings from placement on urgent transplantation list, to continued AB therapy with or without vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy.

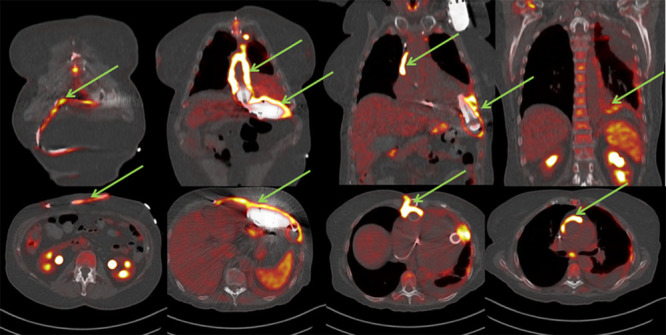

Figure 2.

Case AIII; 59 year old man with inflammation of driveline, subcutaneous part as well as intra-abdominal portion close to pump housing. Beside this there is a strongly suspected osteomyelitis of Lumbar vertebra L5.

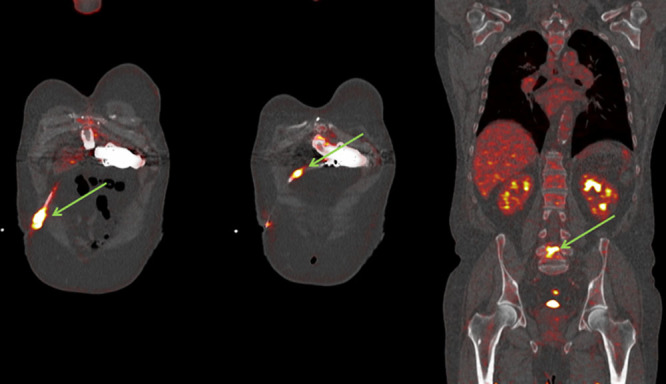

B. Persistent LVAD-specific infection with negative blood cultures: As shown in Figure 3, three patients were found in this group (cases BI–BIII; Table 1). In this group of three patients, clinical symptoms of infection that progressed during AB therapy, despite negative blood cultures, the clinical signs and symptoms of infection were progressive during AB. Figure 3 is an example from this group of patients. These patients (Table 1) were all admitted or unable to be discharged after LVAD implantation because of fever with negative blood cultures. The time between implantation of LVAD and 18F-FDG PET/CT varied from 37 days to 371 days. 18F-FDG PET/CT showed infection of different parts of the LVAD or deep driveline infection despite negative blood cultures, patients had persistent fever.

Figure 3.

A: Case BIII, 61 year old male with example of a deep driveline infection; driveline in situ with subcutaneous fat infiltration visible around the course of the line in the abdominal wall (dotted green arrows). B: In case BIII, the second 18F-FDG PET/CT showed 54 days later persisting and increased metabolic activity around the subcutaneous driveline in abdominal wall. Furthermore, appearance of increased metabolic activity around the outflow cannula of the LVAD near to ascending aortae (green arrows). 18F-FDG PET/CT, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography; LVAD, left ventricular assist devices.

Ongoing AB therapy was accepted in case BI because of extended LVAD-specific infection 37 days after HMII concomitant with aortic valve replacement (AVR). This patient had no deterioration of chronic infection at follow-up of 831 days on continuing LVAD support.

In case BII, there was persisting driveline infection with Staphylococcus aureus 40 days after implantation until HTx and despite several AB regimens and surgical interventions. The abscess around the driveline exit was drained and treatment with intravenous (i.v.) flucloxacillin was started. However, the patient developed recurring cellulitis and the cultures taken from the driveline entrance remained positive despite of AB treatment. The 18F-FDG PET/CT showed high intensity in the abdominal segment because of FDG accumulation along the driveline route. Two hundred days after LVAD implantation she underwent HTx and is still doing well.

In case BIII (Figure 3A), a 61 year old male with LVAD was admitted with a suspected driveline infection caused by cellulites of the abdominal skin at the driveline exit. The cultures showed S. aureus in the driveline exit, but blood cultures were negative. An abdominal ultrasound was performed which showed an infiltrated aspect of the skin. After 16 days of AB therapy, the fluid collection around the driveline decreased. The 18F-FDG PET/CT showed subcutaneous fat infiltration along the driveline with abnormal FDG accumulation. There was no other suspicion of infection beside this deep driveline infection on 18F-FDG PET/CT. The patient was listed for urgent HTx. Despite AB therapy, a control 18F-FDG PET/CT showed extension of increased uptake in the infected region; from the driveline exit to the outflow cannula (Figure 3B). He was transplanted 5 days after the 18F-FDG PET/CT scan. Postoperative cultures of the LVAD showed S. aureus and Candida species.

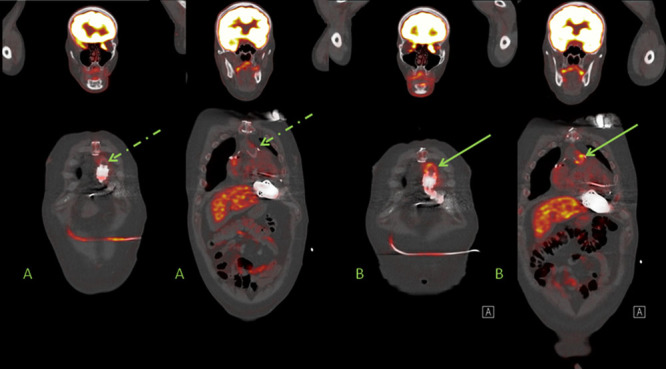

C. LVAD patients with fever of unknown origin and negative cultures: In these three patients, 18F-FDG PET/CT was used after negative blood and swab cultures to either detect or excluded LVAD-specific or -related infection and detect other causes for fever. The first patient (CI in Table 1) is a 75 year old female who received a LVAD as DT. The patient was previously admitted with superficial sternum infection and was treated with empirical AB therapy, however the patient was re-admitted with fever and progression of the sternal wound infection. The 18F-FDG PET/CT showed an infected system and mediastinitis because of migration of the infection. The patient was treated with VAC therapy and AB because of a diffuse infected pump, driveline and mediastinum. There was no other infection unrelated to LVAD, particularly not around the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). At an optimal moment after VAC therapy, a rectus abdominis muscle flap reconstruction was performed 82 days after initiation of AB and VAC therapy to reconstruct the sternal wound. Figure 4 shows this case as an example of the worst case scenario for persisting progressive sternum infections with negative cultures during AB therapy.

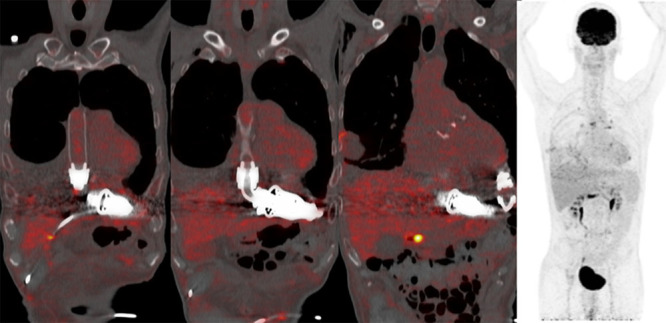

Figure 4.

Case CI: 74 year old female with mediastinitis in diffuse LVAD infection after re-admission because of progressive clinical signs of sternal wound infection during AB treatment. LVAD, left ventricular assist devices; AB, antibiotics.

The second patient (CII in Table 1) is a 54 year old man (Figure 5) with LVAD and concomitant AVR who was admitted to cardiac ICU because of driveline fracture with recurrent LVAD alarms more than two years post LVAD implantation. Because of driveline dysfunction, the LVAD device was exchanged. Three days after surgery because of fever and increased infection parameters, diagnostic CT thorax was performed which showed signs of empyema of the left pleural space. It was treated by thoracic drainage and vancomycin, cefuroxim, clindamycin, and rifampicin for 2 weeks (blood cultures showed growth of Micrococcus luteus and S. aureus). After discontinuation of i.v. AB, oral clindamycin was continued for 1 month. The 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed 24 days after LVAD exchange to monitor the infection and the effect of treatment. There were no signs of an infected LVAD or active infections elsewhere. He is currently alive on LVAD support for more than 3 years.

Figure 5.

Case CII; 54 year old male 24 days after LVAD exchange (678 days on support) PET/CT-guided exclusion of active infection. Mild increased activity around the pleural fluid in the right lung, as well as slightly increased activity in multiple mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes bilaterally as well as in pleural nodular; all possible still reactive. There is no focus of infection. Other finding is subcutaneous emphysema with pneumothorax right sided. LVAD, left ventricular assist devices.

The last patient (CIII; 40 year old male) with LVAD and AVR was admitted for recurrent cardiac tamponade. Because of persisting fever on day 19 post LVAD implantation a thoracic CT scan was done, showing air bubbles in the pericardium which was concluded to be a normal postoperative effect. Ten days later, after initiation of broad spectrum AB for 2 weeks, the 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed which ruled out LVAD infections or prosthetic valve endocarditis. After 410 days on LVAD support, he has no signs of infection at the outpatient clinic.

Discussion

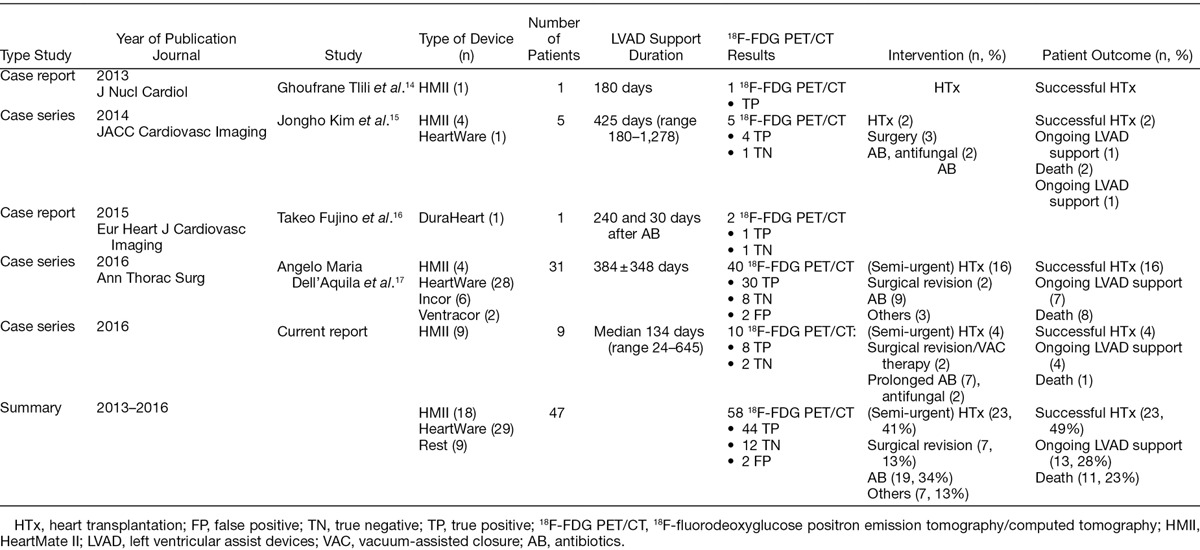

In this paper, we present nine different LVAD patients who suffered from clinically suspected or proven infections in which 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging supported clinical decision-making in LVAD-specific and -related infection. To our best knowledge, our case series contains yet the largest population of HMII patients ever managed by 18F-FDG PET/CT. However, limited data exist regarding the management and outcomes of LVAD infections. In the current literature, we found only 4 studies with case reports and series with a total of 47 cases: 2 case reports and 2 case series with 18F-FDG PET/CT were published between 2013 and 2016. The findings of these four studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of All Published Studies on LVAD-Related Infections and 18F-FDG PET/CT

One of the major drawbacks for long-term LVAD support are LVAD-specific and LVAD-related infections resulting in high risk of morbidity and mortality.12 Prompt diagnosis of LVAD-related infections can be particularly challenging in cases involving pump of cannula infections, pocket infections or deep sternal wound or mediastinal infections. Innovations in cardiovascular imaging strategies have emerged to resolve these issues such as: multi-slice CT, 3D echocardiography, 18F-FDG PET scan, molecular imaging, and cardiac magnetic resonance.

18F-FDG PET/CT appeared to be a useful nuclear imaging diagnostic tool to assess LVAD infections. In a clinical study of 31 LVAD patients, 18F-FDG PET/CT had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 80% of 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting infections of LVAD components, both in patients with and without obvious infection.13 In our current case series we found a sensitivity and specificity of 100% in nine HMII patients including early and very early performed 18F-FDG PET/CT in contrast to previous studies and recommendations. Additionally, the timing when to perform the 18F-FDG PET/CT varies greatly in the current literature (Table 2). Although our sample size is small, 18F-FDG PET/CT was able to evaluate and rule out LVAD infections as early as 3 weeks post-implantation, in contrast to the current paradigm of waiting 3–6 months after LVAD implantation. This was in line with the first paper on nuclear imaging in 8 HMII patients with suspected infection (mean durations after implantation 54 days) without any false positive result.3 In our case series 18F-FDG PET/CT was used to detect the site and extent of infection and to guide duration of AB treatment in 7/9 patients (Table 1). The study accurately ruled out infection in 2/9 patients. Therefore, given the clinical experience in the current literature and our paper, we believe that 18F-FDG PET/CT is a crucial imaging tool in the diagnosis and management in infection specific and related to LVAD patients. However, some issues remain unresolved and require further investigation.

The optimal conditions for 18F-FDG PET/CT acquisition that allows us to improve the image contrast and to better discriminate between positive and negative scans, have to be further determined. 18F-FDG PET/CT could have a widespread use based on practical reasons, however it is limited by meticulous test preparation with low-carbohydrate diet. In the latter circumstance, physiologic myocardial uptake can be seen, reducing the specificity of scan findings. It is therefore unfortunate that among all of the studies reported so far, only two included a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet in addition to the fasting period in the patients’ preparation. Furthermore, image analysis should be standardized regarding both the pattern and the quantification of the uptake. Additionally, the impact of factors such as AB treatment and the type of infective agent needs to be evaluated more precisely. The initiation of AB therapy and, if present, its duration before imaging is likely to alter the inflammatory response of the host and thus FDG uptake.5 Also, it is acknowledged that some bacteria strains may escape immune response either by producing a biofilm on prosthetic material, or by using an intracellular cycle, allowing them to be hardly detectable by immune cells.7

The timing of 18F-FDG PET/CT remains controversial because of recent surgery.13 Nevertheless, in our small cohort there is a promising use of this imaging technique to rule out function even in an early postoperative period (3–6 weeks). Larger studies and comparisons are needed to optimize timing of 18F-FDG PET/CT when there is an ongoing suspicion of LVAD-specific infections without source control in both in the outpatient and inpatient setting. In particular, it is important to define who are the patients that would benefit the most from this test according to their probability of infection based on clinical evaluation, echo(cardio)graphy results and risk factors for development of infection during LVAD support.

Conclusion

In this case series of nine patients with continuous flow LVAD type HMII, 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging provided accurate information on the localization and extent for LVAD-specific or -related infections as early as 3 weeks post-implantation. Review of the current literature with 2 case reports and 2 case series with a total of 47 cases, confirms the promising role of this novel imaging modality.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Mohamud Egal, MD (Department of Intensive Care, Erasmus MC Rotterdam) for his kind suggestions to the previous version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Submitted for consideration June 2016; accepted for publication in revised form February 2017.

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Institutional resources.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.asaiojournal.com).

References

- 1.Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med 2009361: 2241–2251., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannan MM, Husain S, Mattner F, et al. Working formulation for the standardization of definitions of infections in patients using ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 201130: 375–384., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litzler PY, Manrique A, Etienne M, et al. Leukocyte SPECT/CT for detecting infection of left-ventricular-assist devices: preliminary results. J Nucl Med 201051: 1044–1048., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy DT, Minamoto GY, Da Silva R, et al. Role of gallium SPECT-CT in the diagnosis of left ventricular assist device infections. ASAIO J 201561: e5–10., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanis W, Budde RP, van der Bilt IA, et al. Novel imaging strategies for the detection of prosthetic heart valve obstruction and endocarditis. Neth Heart J 201624: 96–107., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akin S, den Uil CA, Groeninx van Zoelen CE, Gommers D.PET-CT for detecting the undetected in the ICU. Intensive Care Med 201642: 111–112., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanis W, Scholtens A, Habets J, et al. CT angiography and ¹8F-FDG-PET fusion imaging for prosthetic heart valve endocarditis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 20136: 1008–1013., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanis W, Scholtens A, Habets J, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography for diagnosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis: increased valvular 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake as a novel major criterion. J Am Coll Cardiol 201463: 186–187., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de By TM, Mohacsi P, Gummert J, et al. The European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support (EUROMACS): first annual report. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 201547(5):770–776.; discussion 776–777, XXX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamar F, Buscombe J, Chiti A, et al. EANM/SNMMI guideline for 18F-FDG use in inflammation and infection. J Nucl Med 201354: 647–658., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boellaard R, Delgado-Bolton R, Oyen WJ, et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 2.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 201542: 328–354., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannan MM, Husain S, Mattner F, et al. Working formulation for the standardization of definitions of infections in patients using ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 201130: 375–384., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dell’Aquila AM, Mastrobuoni S, Alles S, et al. Contributory role of fluorine 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the diagnosis and clinical management of infections in patients supported with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg 2016101: 87–94; discussion 94., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tlili G, Picard F, Pinaquy JB, Domingues-Dos-Santos P, Bordenave L.The usefulness of FDG PET/CT imaging in suspicion of LVAD infection. J Nucl Cardiol 201421: 845–848., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Feller ED, Chen W, Dilsizian V.FDG PET/CT imaging for LVAD associated infections. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 20147: 839–842., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujino T, Higo T, Tanoue Y, Ide T.FDG-PET/CT for driveline infection in a patient with implantable left ventricular assist device. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 201617: 23, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dell’Aquila AM, Mastrobuoni S, Alles S, et al. Contributory role of fluorine 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the diagnosis and clinical management of infections in patients supported with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg 2016101: 87–94; discussion 94., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]