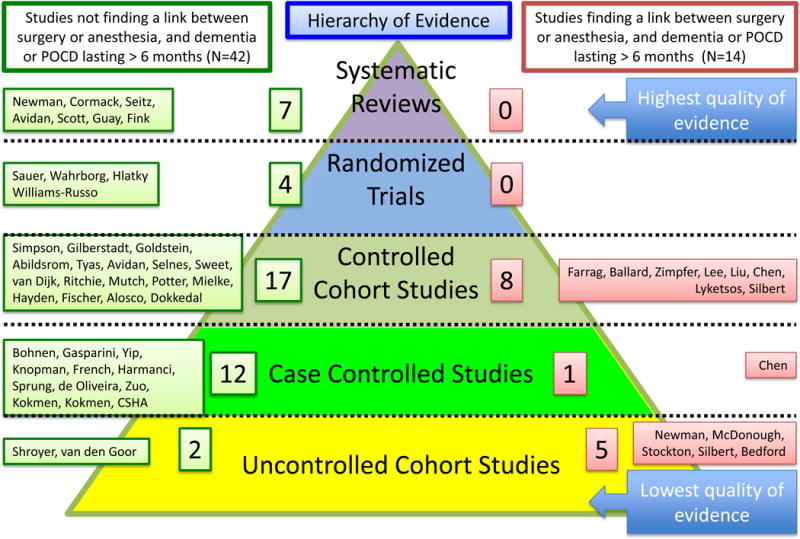

There is a widespread belief in the medical community and lay public that anesthesia and surgery pose a substantial risk of producing long-term cognitive damage in elderly patients. This view endures despite a growing body of clinical research data showing that major surgery and general anesthesia are unlikely to cause persistent postoperative cognitive decline (POCD) or incident dementia. Viewing the studies in an evidential pyramid illustrates that the weight of clinical evidence is heavily tilted against persistent POCD attributable to surgery or anesthesia in older surgical patients. (Figure 1 and Supplementary Online Appendix) The study by Dokkedal et al.1 in this issue of Anesthesiology reinforces this perspective by using a powerful methodological approach. Dokkedal et al. examine the association between exposure to surgery and long-term cognition in a Danish cohort of 8,503 middle aged and elderly twins.1 Their findings substantiate the current evidence of no clinically relevant persistent POCD attributable to surgery or anesthesia, whereas preoperative cognitive trajectory and co-existing disease burden are likely to be strongly predictive of long-term postoperative cognitive trajectory.1 The large number of patients and the use of rigorous longitudinal cognitive testing in this study increased the reliability of the findings, and echoed the results of another twin study that followed World War II veteran twin pairs between 1990 and 2002, and found no negative cognitive effects on the twin who underwent heart surgery.2

Figure 1.

Hierarchy of evidence pyramid showing studies that have and have not found a link between surgery or anesthesia, and dementia or postoperative cognitive decline lasting > 6 months (More details are provided in supplementary online appendix). POCD, postoperative cognitive decline

Historically, some of the landmark studies regarding persistent POCD were in cardiac surgery, which was also included in the study by Dokkedal et al.1 It was generally believed, albeit without compelling evidence, that heart surgery was frequently associated with a cognitive cost, and that this was largely attributable to the cardiopulmonary bypass machine. Importantly, such beliefs were reflected in reputable, mainstream media and have impacted public consciousness to this day. In the New York Times, Sandeep Jauhar wrote, “Studies suggest that anywhere from 10% to 50% or more of bypass patients do poorly on tests of memory, language and spatial orientation 6 months after surgery. These changes can persist years after surgery, and in many cases are probably irreversible.”3 Eric Hawthorne wrote for the British Broadcasting Corporation, “When you go into hospital for heart surgery you do not expect to get brain damage. But that is exactly what is happening to thousands of people a year in Britain.”4

Despite the lack of proof regarding either the cognitive cost or the culpability of the machine, off-pump cardiac surgery was invented and prematurely promoted in an attempt to avoid the hypothetical public health crisis of brain damage after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass, colloquially referred to as “pump-head”.5 It has now been established beyond reasonable doubt that there is no difference in intermediate-term (>6 months) cognitive outcomes regardless of whether cardiopulmonary bypass is used.6,7 The misguided solution of off-pump cardiac surgery was ultimately revealed to pertain to a non-existent problem. It proved financially costly, and importantly was associated with inferior surgical outcomes.6 A recent landmark randomized controlled trial by Sauer and colleagues upended perceived wisdom in finding that patients who underwent heart surgery had better cognitive performance after 7.5 years than patients who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, without any surgery or anesthesia.8 In his editorial contextualizing this trial, Selnes stated, “This study by Sauer and associates adds to a long list of previous studies that by now have convincingly demonstrated that surgical interventions for coronary artery disease are not associated with a higher risk of late cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s disease than medical or nonsurgical interventions.”9 In a systematic review focused on older patients (>65 years) Fink et al summarized, “persistent cognitive impairment after the studied cardiovascular procedures may be uncommon or reflect cognitive impairment that was present before the procedure”.10 Specifically, they found that “CABG [coronary artery bypass grafting] may have little persistent adverse cognitive effect in older adults.”10

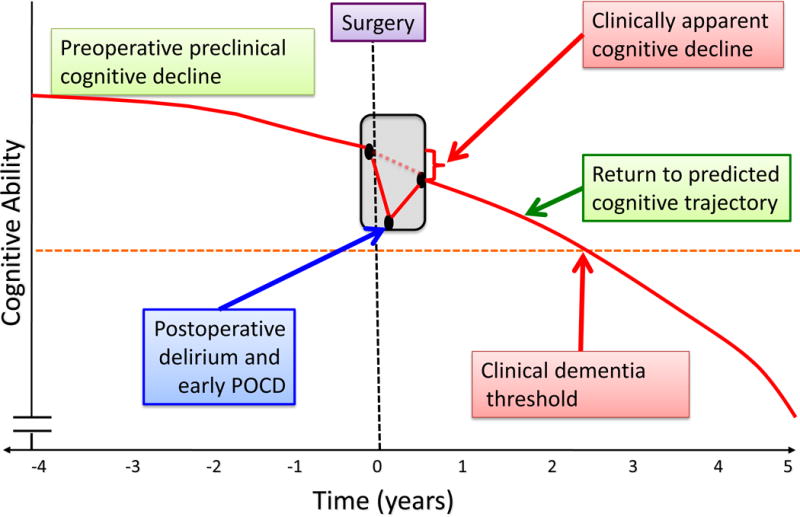

It is interesting to consider why the perceptions of persistent POCD and dementia attributable to surgery endure despite the refutation studies. It is likely that persistent POCD is a powerful example of a post hoc ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this) misattribution fallacy. Anecdote can be very compelling and one often hears about people who were never the same cognitively after their surgery. It might therefore be assumed that the surgery or the anesthesia caused the cognitive change. However, the first time detection of cognitive decline or dementia after surgery is to be expected for several reasons. First, cognitive decline and dementia are common with aging, especially when there are coexisting diseases such diabetes, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, and vascular disease. Similarly, approximately half of people older than sixty undergo a major surgical procedure. Therefore, it is predictable that in some older adults, cognitive decline or dementia will be initially detected following surgery. Second the preoperative cognitive trajectory of surgical patients is not currently assessed. It is likely that many older surgical patients are already experiencing sub-clinical or unappreciated cognitive decline. When they undergo major surgery they are sometimes not seen by friends and colleagues for a few months. In this intervening period, they would continue to decline along their predicted trajectory, but with the time gap, cognitive decline becomes apparent. (Figure 2) Third, it is now appreciated that rapid onset dementia can occur over a period of weeks to months.11 Unsurprisingly this will manifest in some people in the postoperative period. Finally, despite evidential dissonance, it is difficult to change a firmly entrenched belief among many researchers, clinicians and the general public. For all these reasons, when elderly people become demented or experience persistent cognitive decline following a surgical procedure, we suggest that the surgery is usually a coincidence masquerading as the cause.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical preoperative and postoperative cognitive trajectory. POCD, postoperative cognitive decline

It is important that we don’t “throw out the baby with the bath water”. While dementia and persistent cognitive decline are unlikely to be caused by surgery, the brain is vulnerable in the perioperative period, and it is important to mitigate the indisputable neurological consequences of major surgery, including delirium, early POCD, overt stroke and covert stroke. Postoperative delirium is a pathophysiologically obscure, reversible condition characterized by acute onset inattention and disorganized thinking.12 Early POCD is reversible cognitive decline that occurs within days to weeks following surgery.13 Delirium and early POCD are distressing for patients and family members, and are associated with worse outcomes.12,13 Perioperative covert stroke is an under-studied, under-appreciated and potentially preventable complication.14 As such it is important for researchers to focus attention on strategies to prevent postoperative delirium, early POCD, and perioperative stroke.

It is tragic when parents choose not to vaccinate their children against measles because of the persistent fallacy that there is a causal link between vaccination and autism. It is similarly tragic when adults older than 50 forego quality of life-enhancing surgery based largely on hypothesis-generating cohort studies and a post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy dating to a 1955 report by Bedford in the Lancet, which suggested that persistent POCD was a concern following complaints from patients and their families regarding problems with cognitive function after surgery.15 Based on a growing body of evidence, of which the study by Dokkedal et al.1 is emblematic, older patients should today be reassured that surgery and anesthesia are unlikely to be implicated in causing persistent cognitive decline or incident dementia. At the same time, we must energetically seek to alter the dominant narrative on the platform of public opinion, and ensure that reputable media sources correct the misconceptions that they have previously promulgated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are not supported by, nor maintain any financial interest in, any commercial activity that may be associated with the topic of this article.

References

- 1.Dokkedal U, Hansen TG, Rasmussen LS, Mengel-From J, Christensen K. Cognitive functioning after surgery in middle-aged and elderly Danish twins. ANESTHESIOLOGY. 2015 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potter GG, Plassman BL, Helms MJ, Steffens DC, Welsh-Bohmer KA. Age effects of coronary artery bypass graft on cognitive status change among elderly male twins. Neurology. 2004;63:2245–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147291.49404.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jauhar S. Saving the Heart Can Sometimes Mean Losing the Memory. New York Times; 2000. Sep 19, [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawthorne E. Coping with brain damage from heart surgery. British Broadcasting Corporation; 2003. Aug 13, [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck M. ‘Bypass Brain’: How Surgery May Affect Mental Acuity. Wall Street Journal. 2008 Jun 10; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B, Collins JF, McDonald GO, Kozora E, Lucke JC, Baltz JH, Novitzky D, Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) Study Group On-pump versus off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(19):1827–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun JH, Wu XY, Wang WJ, Jin LL. Cognitive dysfunction after off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: a meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:852–8. doi: 10.1177/147323001204000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauër AM, Nathoe HM, Hendrikse J, Peelen LM, Regieli J, Veldhuijzen DS, Kalkman CJ, Grobbee DE, Doevendans PA, van Dijk D, Octopus Study Group Cognitive outcomes 7.5 years after angioplasty compared with off-pump coronary bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(4):1294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selnes OA. Invited commentary. The Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1300–1. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fink HA, Hemmy LS, MacDonald R, Carlyle MH, Olson CM, Dysken MW, McCarten JR, Kane RL, Garcia SA, Rutks IR, Ouellette J, Wilt TJ. Intermediate- and Long-Term Cognitive Outcomes After Cardiovascular Procedures in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(2):107–17. doi: 10.7326/M14-2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geschwind MD, Shu H, Haman A, Sejvar JJ, Miller BL. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:97–108. doi: 10.1002/ana.21430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383:911–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krenk L, Rasmussen LS. Postoperative delirium and postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly - what are the differences? Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:742–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassell ME, Nijveldt R, Roos YB, Majoie CB, Hamon M, Piek JJ, Delewi R. Silent cerebral infarcts associated with cardiac disease and procedures. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10(12):696–706. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedford PD. Adverse cerebral effects of anaesthesia on old people. Lancet. 1955;269:259–63. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(55)92689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.