Abstract

Background

Most patients desire all available prognostic information, but some physicians hesitate to discuss prognosis. We aimed to examine outcomes of prognostic disclosure among parents of children with cancer.

Methods

We surveyed 353 parents of children with newly diagnosed cancer at two tertiary cancer centers, and each child’s oncologist. Using multivariable logistic regression, we assessed associations between parental report of elements of prognosis discussions with the oncologist (quality of information/communication, prognostic disclosure) and potential consequences of these discussions (trust, hope, peace of mind, prognostic understanding, depression, anxiety). Analyses were stratified by oncologist-reported prognosis.

Results

Prognostic disclosure was not associated with increased parental anxiety, depression, or decreased hope. Among parents of children with less favorable prognoses (<75% chance of cure), receipt of high-quality information from the oncologist was associated with greater peace of mind (OR 5.23 [1.81, 15.16]) and communication-related hope (OR 2.54 [1.00, 6.40]). High-quality oncologist communication style was associated with greater trust in the physician (OR 2.45 [1.09, 5.48]) and hope (OR 3.01 [1.26, 7.19]). Accurate prognostic understanding was less common among parents of children with less favorable prognoses (OR 0.39 [0.17, 0.88]). Receipt of high-quality information, high-quality communication, and prognostic disclosure were not significantly associated with more accurate prognostic understanding.

Conclusions

We find no evidence that disclosure is associated with anxiety, depression, or decreased hope. Communication processes may increase peace of mind, trust, and hope. It remains unclear how best to enhance prognostic understanding.

Keywords: prognosis, communication, pediatrics, ethics, disclosure, cancer

INTRODUCTION

Communication is integral to oncology practice,1, 2 but prognostic disclosure varies.3–9 Some oncologists hesitate to discuss prognosis with patients and their families, citing concerns for upsetting them and diminishing hope,4–7 and for the inherent uncertainty of such prognostications.8, 9 Prognosis communication is further complicated by the rise of targeted therapeutics, which can add to prognostic uncertainty.10

Adult cancer patients usually desire all available information about their prognosis.11, 12 Accurate prognostic understanding is important for advanced care planning and end-of-life care, but also to inform decisions about treatment and care plans.13–15 Routinely discussing prognosis is further supported by the physician’s ethical obligation of complete and truthful disclosure out of respect for patient autonomy.2, 13 Our prior work suggests that prognostic disclosure to parents of children with cancer has benefits, including increased hope, trust in the oncologist, and peace of mind.7, 16, 17 Disclosure is desired by parents, even when it upsets them.16 That work has limitations, however, including limited analysis of those with less favorable prognoses, cross-sectional design with variability in timing of survey administration, study of only a single site, and lack of rigorous measurement of psychosocial outcomes of disclosure.

To better understand the impact of prognostic disclosure, in this study we evaluated potential outcomes of discussions about prognosis between parents and oncologists of children with cancer at two tertiary cancer centers. We considered both intended consequences – prognostic understanding, trust in the oncologist, and peace of mind – and unintended consequences – depression, anxiety, and decreased hope – of such discussions (Figure 1). We utilized previously validated measures to assess prognostic disclosure, communication between oncologists and parents, and potential psychosocial outcomes of prognostic disclosure.7, 16–22 We hypothesized that disclosure would not be associated with negative psychosocial outcomes but rather would yield greater understanding of prognosis and increased peace of mind.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of discussions about prognosis in pediatric oncology

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We queried parents of children with cancer and their child’s oncologist between November 2008 and April 2014 at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Survey procedures were reported previously.19 Parents of children with cancer were approached 1 to 6 weeks following diagnosis. The parent who self-identified as primarily responsible for his/her child’s decision-making was invited to take part. The child’s oncologist then was asked to complete a matched survey. Parent surveys were 75 items and included previously validated scales assessing parental report of communication process measures and potential outcomes of prognosis discussions.7, 16–22 Face and content validity was confirmed via 5 parent cognitive interviews; interviewees were selected via purposive selection. Written and electronic surveys were available in Spanish and English, and a $10 gift card was provided to respondents. The Institutional Review Boards of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia approved this study.

Of 565 eligible parents, 382 completed surveys (68%). Ninety-five oncologists completed surveys, matching to 361 (95%) parent surveys. 353 parent-oncologist dyads responded to items addressing the child’s prognosis, providing our final analytic cohort.

Communication process

Parents were asked to report the quality of information delivered by the oncologist regarding their child’s treatment, likelihood of cure, future limitations, cause of the child’s cancer, and overall (excellent, good, satisfactory, fair, poor).7 Quality of the oncologist’s communication style was assessed by asking parents how often he/she provided understandable answers, took enough time to answer parent questions, and conveyed information in a sensitive manner (never, sometimes, usually, always).7 Both indices have been previously validated among parents of children with cancer.7, 14, 19

Prognostic disclosure

Parents were asked to report on prognostic disclosure by the oncologist using a five-item summary score previously validated in this population.7, 17, 19 Items addressed whether the oncologist discussed the child’s prognosis, whether he/she offered the information or the parent had to ask for it, whether prognosis was described generally or numerically, whether prognostic information was written or verbal, and whether the parent was satisfied with the amount of prognostic information received.

Psychosocial outcomes

Symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.22 Peace of mind was assessed according to the peace of mind subscale of the FACIT-Sp, developed for cancer patients21 and validated with parents of children with cancer.17 Additional measured outcomes included parental report of hope related to physician communication (“How often has the way your child’s oncologist communicated with you about your child’s cancer made you feel hopeful?”)7 and trust (“How much do you trust your child’s oncologist’s judgment about your child’s medical care?”),20 both validated in this population.7

Prognosis

Parents and physicians were surveyed independently about the child’s likelihood of cure, with response options of “no chance of cure,” “cure very unlikely (<10% chance),” “unlikely (10–24%),” “somewhat likely (25–49%),” “moderately likely (50–74%),” “very likely (75–90%),” and “extremely likely (>90%).”

Statistical methods

Covariates were dichotomized, as in prior work in this field.7, 17, 20–22 We dichotomized information quality and communication quality at the median.7 Depression and anxiety were dichotomized as scores suggestive (>7) or not suggestive (≤7) of the respective state.22 Peace of mind also was dichotomized, corresponding approximately to the categories (“very” or “extremely”) most indicating strong sense of peace of mind.17, 21 Communication-related hope was dichotomized such that only “always” was coded as indicative of hope.7 Trust in the oncologist was considered similarly, with responses of “completely” coded as positive.7, 20 Prognostic disclosure was scored 0 to 5 according to the total summary score.7

To assess parental understanding of prognosis, parent and oncologist responses were directly compared. Accurate parental understanding of prognosis was defined as any parent response no more than one response category away from the oncologist’s response. We employed this strategy to allow responses that were close – but not necessarily identical – to be considered accurate. For example, if the oncologist response was “moderately likely,” parent responses of “somewhat likely,” “moderately likely,” and “very likely” would be classified as accurate, with all others inaccurate. Defining understanding in this fashion, parental optimism was not possible for the highest two categories. Only one parent was inaccurately pessimistic (responding “unlikely” when the oncologist responded “extremely likely”). Accordingly, parental understanding was analyzed only for those for whom cure was at most “moderately likely” (N=140).

Analyses were stratified by prognosis: less favorable (cure at most moderately likely [likelihood of cure <75%] as reported by the oncologist) and more favorable (cure very or extremely likely, ≥75% likelihood). We stratified by prognosis because understanding of prognosis was applicable only for those with less favorable prognoses (cure at most “moderately likely,” as described above), and we hypothesized that the relationship between communication processes and psychosocial outcomes might vary by prognosis. We performed a subgroup analysis considering parents of children whose likelihood of cure was reported as less than “moderately likely” (<50%).

Bivariable associations between communication processes and parental psychosocial outcomes were conducted using Chi-squared tests; those between prognostic disclosure and parental psychosocial outcomes were assessed with a non-parametric test for trend. Multivariable associations between communication processes and parental psychosocial outcomes were assessed by logistic regression with generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for multiple parents/patients per oncologist. With a type I error rate of 0.05, our sample size of 353 yielded ≥80% power to detect an absolute difference in proportions of 7%, corresponding to ORs of 1.33–1.37 for the psychosocial outcomes measured in this study. In the less favorable prognosis subgroup, multivariable logistic regression with GEE was used to evaluate factors associated with inaccurate parental prognostic understanding. Item non-response was <8% for all measures of interest. Multiple imputation by chained equations was used to impute missing values using the -ice- command in Stata. Imputed values were used for regression analyses but not for descriptive statistics/bivariable analysis. We expect findings to direct future research and did not apply statistical corrections for multiple testing; results should be interpreted in context of having tested for associations with multiple psychosocial outcomes. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the children and parents in the study are provided in Table 1, reported for the overall cohort (N=353) and subdivided by oncologist-reported prognosis: favorable (N=213 [60%]) and less favorable (N=140 [40%]). Participation rates were slightly higher for parents of children with hematologic malignancies and solid tumors than those of children with brain tumors, but not significantly so (p=0.07). Psychosocial outcomes were similar regardless of time to survey completion (data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographics of study cohort, overall and stratified by prognosis

| Overall N=353 |

Less favorable prognosis N=140 |

Favorable prognosis N=213 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age at diagnosis | |||

|

| |||

| 0 to 2 | 93(26%) | 41(29%) | 52(24%) |

| 3 to 6 | 7(20) | 26(19) | 45(21) |

| 7 to 12 | 80(23) | 28(20) | 52(24) |

| 13 to 18 | 109(31) | 45(32) | 64(30) |

|

| |||

| Child gender* | |||

|

| |||

| Male | 154(44) | 68(49) | 86(40) |

| Female | 198(56) | 71(51) | 127(60) |

|

| |||

| Diagnosis | |||

|

| |||

| Hematologic malignancies | 175(50) | 39(28) | 136(64) |

| Solid tumor | 137(39) | 71(51) | 66(31) |

| Brain tumor | 41(12) | 30(21) | 11(5) |

|

| |||

| Physician-rated likelihood of cure | |||

|

| |||

| Extremely likely (>90% chance) | 76(22) | 0(0) | 76(36) |

| Very likely (75–90% chance) | 137(39) | 0(0) | 137(64) |

| Moderately likely (50–74% chance) | 77(22) | 77(55) | 0(0) |

| Less than moderately likely | 63(18) | 63(45) | 0(0) |

|

| |||

| Site | |||

|

| |||

| Boston | 26(74) | 98(70) | 164(77) |

| Philadelphia | 91(26) | 42(30) | 49(23) |

|

| |||

| Parent age* | |||

|

| |||

| < 30 | 36(10) | 17(12) | 19(9) |

| 30 to 39 | 138(40) | 53(39) | 85(41) |

| 40 to 49 | 133(39) | 51(37) | 82(39) |

| 50+ | 38(11) | 16(12) | 22(11) |

|

| |||

| Parent gender* | |||

|

| |||

| Female | 283(81) | 108(78) | 175(83) |

| Male | 66(19) | 31(22) | 35(17) |

|

| |||

| Parent race/ethnicity* | |||

|

| |||

| White non-Hispanic | 275(79) | 112(82) | 163(78) |

| Non-white or Hispanic | 71(21) | 24(18) | 47(22) |

|

| |||

| Parent education* | |||

|

| |||

| High school graduate or less | 122(35) | 48(35) | 74(36) |

| College graduate | 138(40) | 54(39) | 84(41) |

| Graduate/professional school | 85(25) | 36(26) | 49(24) |

|

| |||

| Parent marital status* | |||

|

| |||

| Married/living as married | 289(84) | 117(85) | 172(83) |

| Other | 57(16) | 21(15) | 36(17) |

Child gender was missing for 1; parent age was missing for 8; parent gender was missing for 4; parent race/ethnicity was missing for 7; parent education was missing for 8; and parent marital status was missing for 7.

Communication and prognostic disclosure

Table 2 presents bivariable associations between communication process measures and parent-reported outcomes, stratified by prognosis. In the overall cohort, parents who reported that the oncologist provided high-quality information were more likely to trust him/her “completely” (p<0.001), have peace of mind (p<0.001), and report that physician communication “always” made them feel hopeful (p<0.001) relative to those who reported receiving lower quality information. High-quality information delivery also was associated with decreased anxiety (p=0.01). Similarly, high-quality physician communication style was associated with greater trust in the oncologist (p<0.001), peace of mind (p=0.02), communication-related hope (p=0.02), and decreased anxiety (p=0.02). Comparable findings were seen in both prognostic subsets, and on subgroup analysis for those with likelihood of cure <50% (Supporting Table 1).

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between communication process measures and psychosocial outcomes*

| Number of parents** | Suggestive of depression | Suggestive of anxiety | Strong peace of mind | Hopeful always | Trust completely | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| % | P | % | P | % | P | % | P | % | P | ||

| Entire cohort (N=353) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Overall | 30 | 53 | 30 | 51 | 71 | ||||||

| Information quality | 0.06 | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low | 140 | 34 | 58 | 14 | 28 | 56 | |||||

| High | 194 | 25 | 43 | 39 | 66 | 79 | |||||

| Communication quality | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low | 167 | 32 | 56 | 23 | 35 | 56 | |||||

| High | 179 | 25 | 44 | 34 | 65 | 84 | |||||

| Prognostic disclosure | 0.42 | 0.64 | 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.58 | ||||||

| 0 | 14 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 29 | 86 | |||||

| 1 | 30 | 37 | 60 | 17 | 40 | 63 | |||||

| 2 | 42 | 21 | 57 | 31 | 36 | 57 | |||||

| 3 | 98 | 30 | 46 | 26 | 48 | 73 | |||||

| 4 | 91 | 27 | 52 | 26 | 52 | 67 | |||||

| 5 | 56 | 25 | 45 | 39 | 71 | 77 | |||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Less favorable prognosis subgroup (N=140) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Overall | 30 | 50 | 26 | 40 | 71 | ||||||

| Information quality | 0.48 | 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Low | 70 | 33 | 50 | 11 | 27 | 61 | |||||

| High | 64 | 28 | 41 | 39 | 53 | 78 | |||||

| Communication quality | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.27 | <0.001 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Low | 68 | 35 | 54 | 21 | 25 | 60 | |||||

| High | 70 | 26 | 39 | 29 | 54 | 80 | |||||

| Prognostic disclosure | 0.91 | 0.49 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 0.90 | ||||||

| 0 | 8 | 38 | 38 | 25 | 38 | 100 | |||||

| 1 | 21 | 24 | 57 | 19 | 43 | 67 | |||||

| 2 | 22 | 23 | 55 | 27 | 32 | 55 | |||||

| 3 | 43 | 28 | 35 | 26 | 42 | 67 | |||||

| 4 | 22 | 41 | 55 | 23 | 27 | 73 | |||||

| 5 | 14 | 21 | 36 | 29 | 57 | 79 | |||||

| Understanding | 0.19 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.43 | ||||||

| Inaccurate | 75 | 25 | 45 | 33 | 48 | 73 | |||||

| Accurate | 65 | 35 | 49 | 14 | 29 | 66 | |||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Favorable prognosis subgroup (N=213) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Overall | 29 | 56 | 33 | 57 | 71 | ||||||

| Information quality | 0.07 | 0.003 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low | 70 | 36 | 66 | 16 | 29 | 51 | |||||

| High | 130 | 23 | 44 | 39 | 72 | 80 | |||||

| Communication quality | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low | 99 | 29 | 57 | 24 | 41 | 53 | |||||

| High | 109 | 25 | 48 | 38 | 72 | 87 | |||||

| Prognostic disclosure* | 0.21 | 0.60 | 0.34 | <0.001 | 0.40 | ||||||

| 0 | 6 | 33 | 33 | 50 | 17 | 67 | |||||

| 1 | 9 | 67 | 67 | 11 | 33 | 56 | |||||

| 2 | 20 | 20 | 60 | 35 | 40 | 60 | |||||

| 3 | 55 | 31 | 55 | 25 | 53 | 78 | |||||

| 4 | 69 | 23 | 51 | 28 | 59 | 65 | |||||

| 5 | 42 | 26 | 48 | 43 | 76 | 76 | |||||

P-values for prognostic disclosure from non-parametric test for trend; all others from Chi-squared test

Numbers may not sum to 353, as bivariate analyses were performed on non-imputed data

Prognostic disclosure by the oncologist was not, on bivariable analysis, significantly associated with increased depression or anxiety in the overall cohort (p=0.42 and 0.64, respectively) or in parents of children with less favorable prognoses (p=0.91, p=0.49). Disclosure was associated with greater communication-related hope in the overall and favorable prognosis cohorts (p<0.001, p<0.001), though this finding was not statistically significant in the less favorable prognosis subgroup (p=0.76).

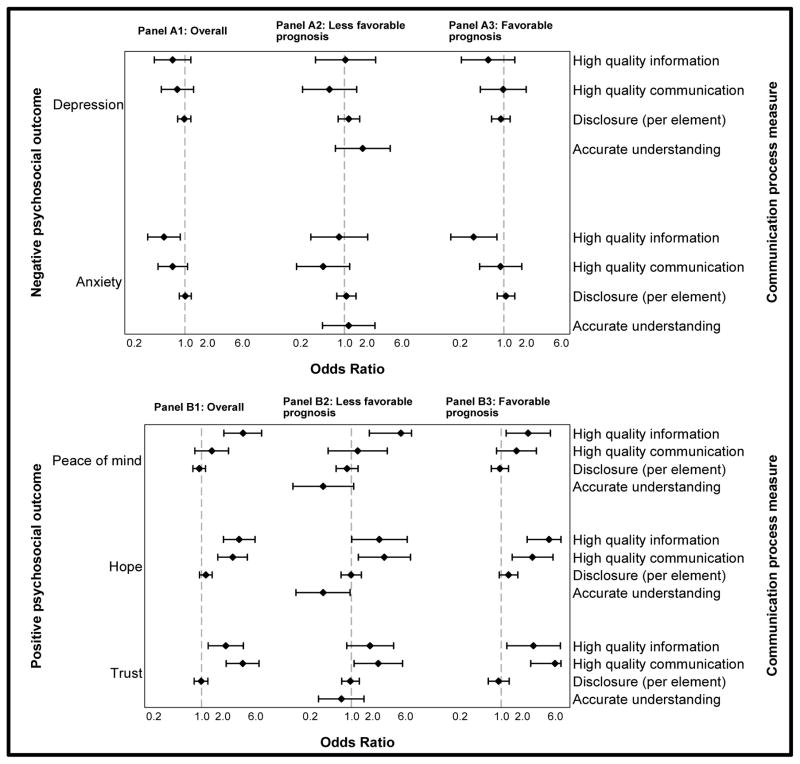

Multivariable relationships between communication processes and psychosocial outcomes are depicted in Figure 2 (raw data in Supporting Table 2). Most bivariable findings persist in these models. In the overall cohort, parents who reported receiving high-quality information more frequently reported peace of mind (OR 3.97 [2.09, 7.57], p<0.001), communication-related hope (OR 3.50 [2.07, 5.92], p<0.001), and trust in the oncologist (OR 2.24 [1.24, 4.02], p=0.01). They less often reported symptoms of anxiety (OR 0.52 [0.38, 0.87], p=0.01). Parents who reported a high-quality physician communication style more frequently reported hope (OR 2.81 [1.71, 4.62], p<0.001) and trust in the oncologist (OR 3.93 [2.26, 6.82], p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of adjusted odds ratios for the association between communication process measures and negative (Panel A) and positive (Panel B) psychosocial outcomes, stratified by prognosis. Panel 1: Overall cohort; Panel 2: Less favorable prognosis subset; Panel 3: Favorable Prognosis subset

Diamonds represent odds ratios and bars represent associated 95% confidence intervals, with upper bounds truncated at 7. Odds ratios adjusted for all communication process measures shown, plus site, child age, gender, and diagnosis; prognosis (for Panel A); and parent age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status. Within-physician clustering accounted for by generalized estimating equations (GEE).

Among parents of children with less favorable prognoses, receipt of high-quality information was associated with greater peace of mind (OR 5.23 [1.81, 15.16] p=0.002) and communication-related hope (OR 2.54 [1.00, 6.40], p=0.05). High-quality physician communication style was associated with increased trust (OR 2.45 [1.09, 5.48], p=0.03) and communication-related hope (OR 3.01 [1.26, 7.19], p=0.01).

In this multivariable model, among parents of children with less favorable prognoses, disclosure was not significantly associated with increased depression (OR 1.15 [0.81, 1.61], p=0.43) or anxiety (OR 1.06 [0.79, 1.44], p=0.69) or decreased hope (OR 0.99 [0.70, 1.39], p=0.94). Prognostic disclosure also was not significantly associated with increased depression or anxiety or decreased hope in the more favorable prognosis subset or in the overall cohort.

Parental understanding of prognosis

Table 3 demonstrates the results of a multivariable logistic regression model evaluating communication processes associated with accurate versus inaccurate parental understanding of prognosis for the less favorable prognosis cohort. Parents were less likely to have an accurate understanding of their child’s prognosis when the oncologist reported that the child’s chance of cure was less than 50% (OR 0.39 [0.17, 0.88], p=0.02) and when the parent was non-white or Hispanic (OR 0.35 [0.12, 1.04], p=0.06), though the latter finding did not achieve statistical significance. No statistical difference was seen according to child’s age, gender, or diagnosis; or according to parent’s age, gender, marital status, or education level. Disclosure was not significantly associated with greater prognostic understanding (OR 0.89 [0.66, 1.20], p=0.45). Accurate understanding of prognosis also was not significantly associated with parental report of receipt of high-quality information (OR 0.45 [0.19, 1.10], p=0.08) or high-quality communication (OR 1.06 [0.47, 2.36], p=0.89) from the oncologist.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model for parental accurate versus inaccurate understanding of prognosis, less favorable prognosis subset*

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information quality (high vs low) | 0.45 | 0.19, 1.10 | 0.08 |

|

| |||

| Communication quality (high vs low) | 1.06 | 0.47, 2.36 | 0.89 |

|

| |||

| Prognostic disclosure (per element) | 0.89 | 0.66, 1.20 | 0.45 |

|

| |||

| Site (Philadelphia vs Boston) | 0.76 | 0.33, 1.74 | 0.76 |

|

| |||

| Child gender (male vs female) | 1.54 | 0.70, 3.40 | 0.29 |

|

| |||

| Child age | 0.47 | ||

|

| |||

| 0–2 | Ref | -- | |

| 3–6 | 0.42 | 0.13, 1.33 | |

| 7 to 12 | 0.50 | 0.15, 1.72 | |

| 13 to 18 | 0.44 | 0.12, 1.64 | |

|

| |||

| Child diagnosis | 0.88 | ||

|

| |||

| Hematologic malignancies | Ref | -- | |

| Solid tumor | 0.81 | 0.31, 2.10 | |

| Brain tumor | 0.96 | 0.33, 2.81 | |

|

| |||

| Child’s prognosis (assessed by oncologist) | 0.02 | ||

|

| |||

| Moderately likely (50–74% chance) | Ref | -- | |

| Less than moderately likely | 0.39 | 0.17, 0.88 | |

|

| |||

| Parent age | 0.12 | ||

|

| |||

| <30 | Ref | -- | |

| 30 to 39 | 3.00 | 0.69, 13.1 | |

| 40 to 49 | 1.27 | 0.23, 6.94 | |

| 50+ | 0.78 | 0.09, 7.08 | |

|

| |||

| Parent gender (male vs female) | 0.92 | 0.35, 2.41 | 0.86 |

|

| |||

| Parent ethnicity | 0.06 | ||

| White non-Hispanic | Ref | -- | |

| Non-white or Hispanic | 0.35 | 0.12, 1.04 | |

|

| |||

| Parent education | 0.89 | ||

|

| |||

| High school graduate or less | Ref | -- | |

| College graduate | 0.84 | 0.33, 2.18 | |

| Graduate/professional school | 1.07 | 0.36, 3.17 | |

|

| |||

| Parent marital status | 0.16 | ||

|

| |||

| Married/living as married | Ref | -- | |

| Other | 0.42 | 0.13, 1.42 | |

OR >1 represent higher likelihood parental report of accurate prognosis.

ORs adjusted for parent-reported information quality, communication quality, prognostic disclosure; site; child age/gender/diagnosis; parent age/gender/race/ethnicity/education/marital status; oncologist-reported prognosis. Within-physician clustering accounted for by GEE

DISCUSSION

We surveyed parents of children with cancer shortly after their child’s diagnosis to consider potential outcomes of prognosis communication and found that prognostic disclosure is not significantly associated with adverse psychosocial outcomes, even in parents of children with less favorable prognoses. Instead, delivery of high-quality information and a high-quality communication style can support parents by instilling hope, peace of mind, and trust in the oncologist. Even when adjusting for prognosis, parents more often report hope and peace of mind when provided high-quality information, indicating that even parents of children with a lower likelihood of cure can experience psychological benefit from forthright discussions with the medical team. While we hypothesize that these benefits result from honest prognostic disclosure, it is possible that hope, peace of mind, and trust may emanate from the communication process rather than disclosure itself. Our study does not allow us to separate these issues. This does not, however, diminish the importance of prognostic disclosure, an ethical responsibility of oncologists2, 13, 23 that is supported by parental preferences.16 Instead, this work highlights the importance of attention to all aspects of communication. Oncologists should pay attention both to what they say and how they say it. Even if positive outcomes primarily are a function of the communication process, these findings reinforce that prognostic disclosure, when occurring within a supportive and caring parent-physician relationship, need not be harmful.

Unfortunately, improved understanding of prognosis – the primary purpose of these discussions – was not associated with prognostic disclosure. Numerous studies in medical oncology have aimed to improve prognostic understanding, but targeted interventions have proven only minimally effective.12, 24–26 Even interventions that have improved prognostic understanding do not appear to maintain improvements over time.27, 28

In our cohort, parents of children for whom cure was less likely more frequently demonstrated inaccurate prognostic understanding, a finding previously reported in this field.18, 29 This highlights the need for greater understanding of how best to convey prognostic information, regardless of prognosis. That accurate understanding of prognosis was associated with decreased communication-related hope among parents of children with less favorable prognoses lends further support to this need but also highlights uncertainty in the relationship between disclosure and positive psychosocial outcomes. Our finding that inaccurate understanding of prognosis was seen more often – though not statistically significantly – among non-white and Hispanic parents reaffirms results of other studies addressing prognosis communication,28, 30–32 raising concerns about justice and equity, particularly given that end-of-life preferences are known to vary by race/ethnicity.31, 33

This work is not without limitations. We focused on parents’ reports soon after diagnosis; it is possible that prognostic discussions are perceived differently later in treatment and that these discussions would be perceived differently by an outside/objective party. Parental perception of communication is key, however, so parental report is particularly meaningful. Additionally, it is possible that parental hope and trust support parents’ perception of physician communication processes, rather than the reverse; we cannot make determinations of causality or directionality from this work. Furthermore, though the breakdown of cancer diagnoses examined in this cohort is similar to that seen nationally,34 the preponderance of children with hematologic malignancies led to a relative paucity of patients with solid tumors and brain tumors, diagnoses that can portend worse prognoses. Though medical advances have reduced the number of children with very poor prognoses, it is conceivable that parents of children with particularly bleak prognoses have different perspectives on discussions of prognosis that are not adequately captured in this study. That our subgroup analysis considering parents of children with less than a 50% likelihood of cure showed similar results to our primary analyses helps assuage these concerns, however.

Children with up to a 75% likelihood of cure were included in our “less favorable prognosis” cohort, and some might argue that this cohort is not adequately representative of those with very poor prognoses. The similar findings in the aforementioned subgroup analysis and the similarity of the overall cohort to the characteristics of children diagnosed with cancer nationwide,34 however, support the generalizability of this work. Because parents were enrolled at two large academic centers, it is possible that results are less relevant to children treated in smaller and/or non-academic settings. As is recommended, most children with cancer in the United States are primarily cared for at such pediatric cancer centers,35 so these results should be applicable to most pediatric cancer patients. Finally, this work focused on discussions with parents and did not evaluate children’s experiences. As part of a related study, we interviewed older children and adolescents and found that many also desire prognostic information.36

In conclusion, despite oft-cited concerns otherwise, prognostic disclosure does not appear to harm the parent-oncologist relationship in pediatric oncology, but can actually strengthen it. Accordingly, this work strengthens the argument that pediatric oncologists should feel comfortable discussing prognosis with all parents of children with cancer, even when the child’s prognosis is less favorable. Disclosure alone appears inadequate to improve parental prognostic understanding, however.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32 CA136432), an American Society of Clinical Oncology Conquer Cancer Foundation (ASCO/CCF) Merit Award, and support from Pedals for Pediatrics and the Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics (JMM); and an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant and ASCO/CCF Career Development Award (JWM).

Footnotes

Previously presented in part at the 51st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, May 29 – June 2, 2015 and the 2015 Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium, Boston, MA, October 9–10, 2015.

No authors have conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Contributions

Marron: Data analysis/interpretation, writing, approval of final version, manuscript guarantor.

Cronin: Data analysis/interpretation, writing, approval of final version.

Kang: Collection/assembly of data, data analysis/interpretation, writing, approval of final version.

Mack: Conception/design, collection/assembly of data, data analysis/interpretation, writing, approval of final version.

References

- 1.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. Patient-Clinician Communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2311. JCO2017752311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 6. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daugherty CK, Hlubocky FJ. What are terminally ill cancer patients told about their expected deaths? A study of cancer physicians’ self-reports of prognosis disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5988–5993. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon EJ, Daugherty CK. ‘Hitting you over the head’: oncologists’ disclosure of prognosis to advanced cancer patients. Bioethics. 2003;17:142–168. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The AM, Hak T, Koeter G, van Der Wal G. Collusion in doctor-patient communication about imminent death: an ethnographic study. BMJ. 2000;321:1376–1381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, Tattersall MH. Fostering coping and nurturing hope when discussing the future with terminally ill cancer patients and their caregivers. Cancer. 2005;103:1965–1975. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5636–5642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:469–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AK, White DB, Arnold RM. Uncertainty--the other side of prognosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2448–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1303295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temel JS, Shaw AT, Greer JA. Challenge of Prognostic Uncertainty in the Modern Era of Cancer Therapeutics. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:3605–3608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, et al. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 1997;277:1485–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of Prognostic Disclosure: Associations With Prognostic Understanding, Distress, and Relationship With Physician Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3809–3816. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mack JW, Joffe S. Communicating about prognosis: ethical responsibilities of pediatricians and parents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(Suppl 1):S24–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3608E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenzang KA, Cronin AM, Mack JW. Parental preparedness for late effects and long-term quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2016;122:2587–2594. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9146–9154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5265–5270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Peace of mind and sense of purpose as core existential issues among parents of children with cancer. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:519–524. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1357–1362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mack JW, Cronin AM, Kang TI. Decisional Regret Among Parents of Children With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the Trust in Physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychol Rep. 1990;67:1091–1100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. Patient-Clinician Communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017:11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of a Patient-Centered Communication Intervention on Oncologist-Patient Communication, Quality of Life, and Health Care Utilization in Advanced Cancer: The VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:92–100. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith TJ, Dow LA, Virago EA, Khatcheressian J, Matsuyama R, Lyckholm LJ. A pilot trial of decision aids to give truthful prognostic and treatment information to chemotherapy patients with advanced cancer. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein AS, Prigerson HG, O’Reilly EM, Maciejewski PK. Discussions of Life Expectancy and Changes in Illness Understanding in Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2398–2403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4131–4137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trevino KM, Zhang B, Shen MJ, Prigerson HG. Accuracy of advanced cancer patients’ life expectancy estimates: The role of race and source of life expectancy information. Cancer. 2016;122:1905–1912. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KJ, Tieves K, Scanlon MC. Alterations in end-of-life support in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e859–864. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corrigan JJ, Feig SA. Guidelines for pediatric cancer centers. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1833–1835. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brand SR, Fasciano K, Mack JW. Communication preferences of pediatric cancer patients: talking about prognosis and their future life. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:769–774. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3458-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.