Abstract

The autonomic nervous system exerts broad control over the involuntary functions of the human body via complex equilibrium between sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. Imbalance in this equilibrium is associated with a multitude of cardiovascular outcomes, including mortality. The cardiovascular static state of this equilibrium can be quantified via physiological parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure and by spectral analysis of heart rate variability.

Here we review the current state of knowledge of the genetic background of cardiovascular measurements of autonomic tone. For most parameters of autonomic tone a large portion of variability is explained by genetic heritability. Many of the static parameters of autonomic tone have also been studied via candidate gene approach, yielding some insight into how genotypes of adrenergic receptors affect variables such as heart rate. Genome-wide approaches in large cohorts similarly exist for static variables such as heart rate and blood pressure, but less is known about the genetic background of the dynamic and more specific measurements, such as heart rate variability. Furthermore, because most autonomic measures are likely polygenic, pathway analyses and modeling of polygenic effects are critical. Future work will hopefully explain the control of autonomic tone and guide individualized therapeutic interventions.

Subject Codes: Autonomic Nervous System, Cardiovascular Disease, Genetics

Introduction

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) exerts intricate, nearly global control of all involuntary functions of the human body. Through reciprocal and cooperative activation of the two divisions of the ANS, the sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways, the ANS plays a critical role in homeostatic regulation.(1) In addition to regulating homeostasis, the ANS generates rapid hemodynamic and neuroendocrine responses to stressors.(2) Though the ANS regulates a diverse group of functions ranging from pupillary diameter to genitourinary function,(3) autonomic control of cardiovascular function has received increased interest. Autonomic function has been hypothesized to be central to the pathophysiology of heart failure,(4) hypertension,(5) and arrhythmias.(6, 7) While aspects of autonomic function are heritable and may predispose individuals to disease states,(8) very little is known about the genetic underpinnings of autonomic function. With the development of affordable assays to measure not just the overall genetic contribution to physiologic variables but also test for association with candidate genes or perform hypothesis -generating genome wide association studies (Table 1), the understanding of the genetic underpinning of autonomic function is gradually emerging. In this review, we outline the measurement of autonomic function, implications for disease pathogenesis, and the current state of knowledge regarding heritability and genetic determinants of autonomic function, with a focus on cardiovascular disease.

Table 1.

Methods to study genetic association with physiologic variables or pathologic states.

| Measurement | Description |

|---|---|

| Heritability study | For continuous variables (such as heart rate) The covariance of the dizygous twins accounts for environmental influences, and a portion of the genetic influences on the variable (since they share 50% of the DNA). The difference between the covariance in a group of monozygous twins and the covariance in a group of dizygous twins is an estimate of the genetic contribution to the variable. |

| Candidate gene study | A list of biologically plausible genes is generated from existing literature (i.e. genes involved in the acetylcholine pathway). The outcome variable is correlated with the genotype of variants (i.e. single nucleotide polymopisms) within these genes. |

| Genome-wide association study | The genotype of genetic variants (such as single nucleotide polymorphisms or microsatellite markers) distributed around the genome is compared between cases and controls. Most commonly non-protein coding variants. Areas with different frequency genotypes between cases and controls are potentially involved in pathogenesis of disease. |

Autonomic Tone: Definition, measurement, heritability, and uses as prognostic markers

Defined simply, “autonomic tone” can be conceptualized as a rheostat balancing the two ANS divisions—the sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways. Though much of the autonomic nervous system trafficking is processed via reflex mechanisms, this likely omits a great deal of higher-order physiologic complexity in autonomic regulation.(9) In the following section, we will outline a number of cardiovascular measures of autonomic tone, their utility as markers of health and disease, and available evidence regarding their heritability.

1. Heart Rate

Heart rate—the number of times per minute that the heart generates an electrical depolarization—is largely under control of the sinoatrial node, which is reciprocally regulated by autonomic effects on spontaneous diastolic depolarization. In general, sympathetic stimulation results in an increase in heart rate, whereas parasympathetic stimulation results in a decrease in heart rate.(10) Interestingly, while sympathetic stimulation shortens action potential duration (APD) in both ventricular and atrial myocardium, parasympathetic stimulation prolongs APD and effective refractory period (ERP) in the ventricles, but shortens APD and ERP in the atria. This phenomenon may account for the fact that vagal stimulation is arrhythmogenic in the atria, but anti-arrhythmic in the ventricles.(6)

Resting heart rate may serve as a potential marker of health and/or disease. In patients with cardiovascular disease, increased resting heart rate was associated with worsened cardiovascular outcomes.(11) Additionally, increased resting heart rate was also predictive of incident heart failure in a population without known cardiac disease,(12) as well as all-cause mortality in individuals over age 60.(13) Interestingly, increased resting heart rate is also associated with chronic orofacial pain.(14, 15) Conversely, a low-resting heart rate is associated with later development of atrial fibrillation.(16) Taken together, this suggests that shifts of autonomic tone toward sympathetic predominance may increase risk or progression of sympathetically mediated conditions, such as heart failure and chronic pain, whereas excessive parasympathetic tone may act as a trigger for atrial arrhythmias. While age and sex differences exist in resting heart rate,(13) the genetic underpinnings of these differences remain unclear.

a. Heritability of resting HR

Several authors have assessed the heritability of resting HR. A higher correlation was found between the resting HR of siblings than spouses of participants in the Framingham Heart Study.(17) Similarly heritability was estimated to explain 40% of the variability in resting HR comparing related to unrelated individual in a study of Chinese and Japanese cohorts.(18) A study comparing ECG measurements between 251 pairs of twins found that heritability explained 77% of the variability in HR.(19) Similarly, a study comparing the correlation of both resting HR and HR following a mental calculation task between 372 pairs of monozygous and dizygous twins suggested that heritability explained about 63–69% of the variability in both variables.(20)

b. Candidate gene studies of resting HR

Several candidate genes have been suggested to affect resting HR, especially within the adrenergic receptors (Table 2). A variant (Ser49Gly) within the beta-1 adrenergic receptor was found to be associated with resting heart rate in a cohort of 1348 Chinese/Japanese individuals.(18) The same variant was also associated with resting HR in hypertensive African-Americans and Caucasian individuals taking beta-blockers in cohorts of 1337 and 1685 individuals, respectively.(21) Other variants of beta-1 receptors have additionally been associated with a differential response to beta-blocking therapy.(22) Other variants in the alpha-2 receptor was similarly associated with resting HR in subpopulations of Caucasian and African-American individuals.(21)

Table 2.

List of identified genetic variants associated with variables describing autonomic tone, associated genes, key publication describing each variant, and minor allele frequency (MAF) of variants found in Caucasian population. Note that more than one publication can include a description of variant. Also note that several genes can be adjacent to a single nucleotide variant associated with a physiological parameter. All studies were population based, there were no familial studies.

| SNP | Feature | Associated.Gene | Publication | Type of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1799998 | Baroreceptor sensitivity | CYP11B2 | Ylitao et al. and Xing-Sheng et al. | Candidate gene |

| NA | Baroreceptor sensitivity | NOS3 | Xing-Sheng et al. | Candidate gene |

| NA | Baroreceptor sensitivity | BDKRB2 | Xing-Sheng et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs11195419 | Blood pressure | ADRA2A | Sober et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs10077885 | Blood pressure | TRIM36 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs10760117 | Blood pressure | PSMD5 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs10889553 | Blood pressure | LEPR | Sober et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs11105354 | Blood pressure | ATP2B1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs11128722 | Blood pressure | FGD5 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs11195417 | Blood pressure | ADRA2A | Sober et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs11556924a | Blood pressure | ZC3HC1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1156725 | Blood pressure | PLEKHA7 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs11953630 | Blood pressure | EBF1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs12243859 | Blood pressure | CACNB2 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs12247028 | Blood pressure | SYNPO2L | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs12627651 | Blood pressure | CRYAA–SIK1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs12656497 | Blood pressure | NPR3–C5orf23 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs12705390 | Blood pressure | PIK3C G | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs12940887 | Blood pressure | ZNF652 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs12958173 | Blood pressure | SETBP1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs13107325a | Blood pressure | SLC39A8 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1327235 | Blood pressure | JAG1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1361831 | Blood pressure | RSPO3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1371182 | Blood pressure | FIGN–GRB14 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1450271 | Blood pressure | ADM | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1458038 | Blood pressure | FGF5 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1620668 | Blood pressure | ST7L–CAPZA1–MOV10 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs17010957 | Blood pressure | ARHGAP24 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs17037390a | Blood pressure | MTHFR–NPPB | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs17080093 | Blood pressure | PLEKHG1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs17097182 | Blood pressure | LEPR | Sober et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs17608766 | Blood pressure | GOSR2 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs17638167 | Blood pressure | ELAVL3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1799945a | Blood pressure | HFE | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1975487 | Blood pressure | PNPT1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2187668 | Blood pressure | BAT2–BAT5 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2272007a | Blood pressure | ULK4 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2291435 | Blood pressure | TBC1D1–FLJ13197 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2493134a | Blood pressure | AGT | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2521501 | Blood pressure | FURIN–FES | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2586886 | Blood pressure | KCNK3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2594992 | Blood pressure | HRH1–ATG7 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2891546 | Blood pressure | TBX5–TBX3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2898290 | Blood pressure | BLK–GATA4 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs2969070 | Blood pressure | CHST12–LFNG | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs3184504a | Blood pressure | SH2B3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs3735533 | Blood pressure | HOTTIP–EVX | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs3741378a | Blood pressure | SIPA1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs3752728 | Blood pressure | PDE3A | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs4245739 | Blood pressure | MDM4 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs4247374 | Blood pressure | INSR | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs4691707 | Blood pressure | GUCY1A3–GUCY1B3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs592373 | Blood pressure | LSP1–TNNT3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs6026748 | Blood pressure | GNAS–EDN3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs6271a | Blood pressure | DBH | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs633185 | Blood pressure | FLJ32810–TMEM133 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs6442101a | Blood pressure | MAP4 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs6779380 | Blood pressure | MECOM | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs6891344 | Blood pressure | CSNK1G3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs6919440 | Blood pressure | ZNF318–ABCC10 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs7076398 | Blood pressure | C10orf107 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs7103648 | Blood pressure | RAPSN | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs711737 | Blood pressure | SLC4A7 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs7213273 | Blood pressure | PLCD3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs740746 | Blood pressure | ADRB1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs7515635 | Blood pressure | HIVEP3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs751984 | Blood pressure | LRRC10B | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs772178 | Blood pressure | NCAPH | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs880315 | Blood pressure | CASZ1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs918466 | Blood pressure | ADAMTS9 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs932764a | Blood pressure | PLCE1 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs936226 | Blood pressure | CYP1A1–ULK3 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs943037 | Blood pressure | CYP17A1–NT5C2 | Ehret et al. | GWAS |

| rs1042713 | Cold pressor test | ADRB2 | Li et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs16887217 | Cold pressor test | STAR | Hong et al. | GWAS |

| rs16991617 | Cold pressor test | MCM8 | Yang et al. | GWAS |

| rs17020502 | Cold pressor test | CTNNA2 | Hong et al. | GWAS |

| rs2006765 | Cold pressor test | AGT | Wang et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs2326373 | Cold pressor test | SMOX | Yang et al. | GWAS |

| rs3087776 | Cold pressor test | CYB561 | Zhang et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs4681443 | Cold pressor test | AGTR1 | Wang et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs4959677 | Cold pressor test | MYLK4 | Hong et al. | GWAS |

| rs6052943 | Cold pressor test | SLC23A2 | Yang et al. | GWAS |

| rs6356 | Cold pressor test | TH | Rao et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs6715049 | Cold pressor test | CTNNA2 | Hong et al. | GWAS |

| rs6736587 | Cold pressor test | CTNNA2 | Hong et al. | GWAS |

| rs6756959 | Cold pressor test | CTNNA2 | Hong et al. | GWAS |

| rs6892553 | Cold pressor test | ACTBL2 | Hong et al. | GWAS |

| rs7098785 | Cold pressor test | PIK3AP1 | Hong et al. | GWAS |

| rs1050288 | Heart rate | KLHL42 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs10739663 | Heart rate | MAPKAP1 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs10841486 | Heart rate | PDE3A | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs10880689g | Heart rate | ALG10B | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs11083258 | Heart rate | CDH2 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs11118555 | Heart rate | CD46 | den Hoed et al. | GWAS |

| rs11454451 | Heart rate | GPATCH2 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs11563648 | Heart rate | ZNF800 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs11920570 | Heart rate | CCDC58 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs12501032 | Heart rate | PPARGC1A | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs12576326 | Heart rate | TP53I11 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs12579753 | Heart rate | PPFIA2 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs1260326 | Heart rate | GCKR | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs12713404 | Heart rate | BCL11A | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs12721051 | Heart rate | APOE; APOC1; PVRL2 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs12889267 | Heart rate | NDRG2; ARHGEF40; ZNF219 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs13165531 | Heart rate | CDH6 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs138186803 | Heart rate | MKLN1 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs145358377 | Heart rate | RNF207; ICMT | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs1468333f | Heart rate | CDC23 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs1483890 | Heart rate | FRMD4B | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs1549118 | Heart rate | ADCK1 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs16974196 | Heart rate | C19orf47; MAP3K10 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs17180489 | Heart rate | RGS6 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs17265513 | Heart rate | ZHX3; EMILIN3 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs1801252 | Heart rate | ADRB1 | Eppinga et al., Ranade et al, Wilk et al. | GWAS |

| rs2076028 | Heart rate | SUN2; CBY1; FAM227A; JOSD1; TOMM22; DDX17; GTPBP1 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs2152735 | Heart rate | LMO4 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs2283274 | Heart rate | CACNA1C | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs2358740 | Heart rate | CACNA1D | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs236349 | Heart rate | PPIL1 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs272564 | Heart rate | RNF220 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs365990 | Heart rate | MYH6 | Holm et al. | GWAS |

| rs3749237 | Heart rate | IP6K1; GMPPB; FAM212A; DAG1; KLHDC8B; LAMB2; PRKAR2A; QRICH1 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs3915499 | Heart rate | MYH11 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs41312411 | Heart rate | SCN5A | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs41748 | Heart rate | MET | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs4608502 | Heart rate | COL4A3 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs4900069 | Heart rate | C14orf159 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs56233017 | Heart rate | PLEC | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs564190295 | Heart rate | WIPF1 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs58437978 | Heart rate | TBX20 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs61735998 | Heart rate | FHOD3 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs6845865 | Heart rate | ARHGAP10; EDNRA | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs7194801 | Heart rate | CDH11 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs75190942 | Heart rate | KCNJ5; C11orf45 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs79121763 | Heart rate | TEKT3; PMP22 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs867400 | Heart rate | RASSF3 | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rs907683 | Heart rate | SPEG; DES | Eppinga et al. | GWAS |

| rsl015451 | Heart rate | GJA1 | den Hoed et al. | GWAS |

| rsl3245899 | Heart rate | ACHE | den Hoed et al. | GWAS |

| rsl7287293 | Heart rate | LINC00477 (C12orf67) | den Hoed et al. | GWAS |

| rsl74549 | Heart rate | FADS1 | den Hoed et al. | GWAS |

| rs11153730 | Heart rate | SLC35F1 | den Hoed et al. | GWAS |

| rs12974991, rs12974440, rs12980262 | Heart rate variability | NDUFA11 | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs10842383 | Heart rate variability | LINC00477 (C12orf67) | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs236349 | Heart rate variability | PPIL1 | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs7980799, rs1351682, rs1384598 | Heart rate variability | SYT10 | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs4262, rs180238 | Heart rate variability | GNG11 | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs4899412, rs2052015, rs2529471, rs36423 | Heart rate variability | RGS6 | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs2680344 | Heart rate variability | HCN4 | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs1812835 | Heart rate variability | NEO1 | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs6123471 | Heart rate variability | KIAA1755 | Nolte et al. | GWAS |

| rs11191548 | Orthotatism | CYP17A1 | Fedoeowski et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs11953630 | Orthotatism | EBF1 | Fedoeowski et al. | Candidate gene |

| rs4149601 | Orthotatism | NEDD4L | Luo et al. | Candidate gene |

| NA | Orthotatism | GNB3 | Tabara et al. | Candidate gene |

| NA | Orthotatism | GNAS1 | Tabara et al. | Candidate gene |

c. Genome-wide studies of resting HR

Multiple genome-wide association studies have been performed on resting HR in several populations (Table 2). The first association identified via GWAS of two populations with 10,000 individuals each was with rs365990, a missense variant in the myosin heavy chain alpha isoform (MYH6).(23) Later studies expanded the cohorts used in the original GWAS studies to include a total of 181,171 individuals.(24) These confirmed prior loci and added 14 additional loci, with loci also associated with dilated, hypertrophic and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, regulation of heart contraction, cell adhesion, energy metabolism and Alzheimer’s disease. Most recently, 64 loci, including 46 not previously described, were found to be significantly associated with resting heart rate in a study of 19.9 million variants in up to 265,046 individuals.(25) These included multiple loci on all but three autosomal chromosomes. Interestingly none of the variants identified via GWAS approach include beta-adrenergic receptors, the focus of candidate approaches. This highlights the utility of using data-driven approaches to identify novel pathways associated with cardiovascular and autonomic phenotypes.

2. Blood Pressure, systemic vascular resistance, and baroreceptor response

The autonomic nervous system exerts complex control over blood pressure through regulation of cardiac function, vascular resistance, intravascular volume, and integration of sensory inputs.(26) Short-term perturbations of blood pressure are sensed in large part by arterial baroreceptors, which then modulate efferent sympathetic and parasympathetic trafficking. While chronotropic responses to changes in blood pressure largely rely on the parasympathetic nervous system, the sympathetic nervous system exercises greater control over peripheral vascular tone as well as cardiac function.(27) Indeed, neurodegenerative disorders affecting the sympathetic nervous system often result in symptomatic hypotension due to failure of part of the baroreceptor reflex arc.(28) The role of the sympathetic nervous system in chronic blood pressure elevation is well appreciated, with numerous studies demonstrating sympathetic hyperactivity in patients with both early and established hypertension.(29) Indeed, many pharmacologic treatments for hypertension aim to reduce the sympathetic hyperactivity that is thought to play a central role in the pathogenesis of hypertension.(30) Additionally, emerging non-pharmacologic strategies for the management of hypertension include modulation of sympathetic tone.(27)

The role of blood pressure as a marker of health and disease is well established. Orthostatic hypotension is associated with a higher risk of incident stroke and coronary artery disease.(31) Similarly, failure to appropriately augment blood pressure in response to physical exercise is associated with higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.(32) Hypertension—elevated resting blood pressure—is an extremely common medical condition that increases risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and renal disease.(33) To mitigate these risks, current guidelines recommend careful treatment of hypertension,(34) though recent trials might result in changes in target blood pressure.(35) Evidence suggests that gender and race may impact adrenergic receptor responsiveness, thereby mediating vascular resistance.(36)

a. Heritability of resting blood pressure, systemic vascular resistance, and baroreceptor response

Heritability in measurements of both systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure has been established, with the correlation of both resting BP and BP responses to a mental stressor (mental arithmetic) using twin pairs, revealed that 49–72% of the variability in DBP and SBP was explained by heritability.(20) Similarly, utilizing a high-density SNP genotyping in two large cohorts, 20–27% and 39–50% of the variability in SBP and DBP was explained by heritability.(37) In a family study with 444 individuals, both 23% of blood pressure and 39% variability in pulse pressure was found to be explained by heritability.(38) In 172 pairs of twins utilizing a non-invasive measurement of cardiac output, the heritability of systemic vascular resistance was found to be 59%.(39) Finally, heritability explained 36–44% of the variability in measurements of baroreceptor sensitivity, measured as the slope between instantaneous blood pressure and subsequent R-R interval in a study of 149 twin pairs.(40)

b. Candidate gene studies of resting blood pressure

Few authors have attempted association of plausible candidates to blood pressure variation (Table 2). Screening individuals from the Framingham heart study for variants in genes associated with salt handling known to cause familial hyper-or hypotension (SLC12A3, SLC12AI, KCNJ1), 138 coding sequence variants were identified in 2,492 individuals.(41) Individuals carrying the rare variants had a significantly lower SBP than individuals without them. Additionally, variants within 160 genes with a biological link to hypertension were assessed for association with measurements of blood pressure in three cohorts, revealing only a weak association for variants with two of the genes (LEPR, ADRA2A) and blood pressure.(42) There was only a weak association between homozygotes for variants in the Rho/rho kinase isoform 2 gene (ROCK2) and systemic vascular resistance.(39) Baroreceptor reflex, measured as the blood pressure response to a Valsalva maneuver, differed between variants in the aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2).(22) Another study, quantifying baroreceptor reflex sensitivity by measuring the fluctuation between systemic blood pressure and R-R interval, also identified association between the response and variants in the CYP11B2 gene and both the bradykinin B2 receptor (BDKRB2) and the endothelial nitrous oxide (NOS3) synthase gene.(43)

c. Genome-wide studies of blood pressure

Original genome-wide approaches in a sample of 14,000 individuals identified no genetic regions associated with a diagnosis of hypertension.(44) Increasing the number of patients by combining multiple large consortia of individuals have subsequently identified more than 60 loci associated with quantitative measurements of blood pressure, each with a relatively small contribution to the phenotype (Table 2).(45–47) This highlights the challenges in mapping and understanding how very complex genetic interactions contribute to blood pressure regulation.

3. Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

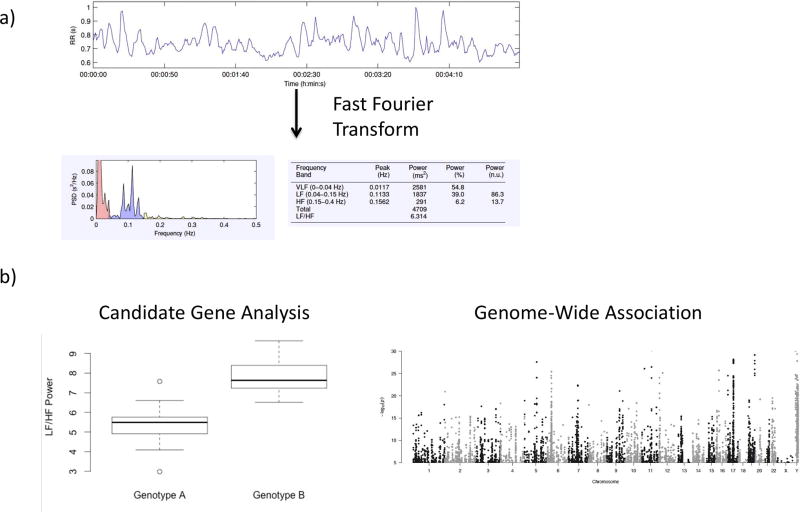

As one of the primary controllers of heart rate, the autonomic nervous system plays a large role in dictating the length of the inter-beat interval—the length of time between each heartbeat. These beat-to-beat fluctuations in heart rate can be measured with a variety of technologies, and interpreted over short (i.e. 5 minutes) or long (i.e. 24 hours) periods of time. Short recordings are typically analyzed using frequency-domain measures, which group inter-beat fluctuations into several defined frequency spectra of high frequency (HF), low frequency (LF), and very low frequency (VLF) (Figure 1a). Additionally, normalized measurements of high frequency (HF/HF+LF), low frequency (LF/HF+LF) and ratio of LF/HF have been utilized as surrogate markers of autonomic tone. The quantification of the fluctuation within each frequency spectra can then be utilized for analysis of the genetic background of autonomic tone (Figure 1b). Similarly, long recordings of inter-beat intervals may be analyzed using frequency domain or time-domain techniques, which quantitatively describe the variability as normal-normal intervals.(48) The variability is then traditionally described as standard deviation of normal-normal interval (SDNN), root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) and percentage of successive intervals with more than 50 ms difference (pNN50). Additionally, multiple novel analytic techniques, which are beyond the scope of this review, may provide insight into autonomic tone.(49) In both healthy controls(50) and patients with risk factors for cardiovascular disease,(51) levels of adrenergic hormones correlate with frequency domain measures of HRV. Similarly, cardiac norepinephrine spillover correlates with non-linear measures of HRV complexity.(52)

Figure 1.

Example of the analysis of the genetic background of heart rate variability: a) RR interval (time between heart beats) are collected over 5 minutes, and spectral analysis performed by fast Fourier transform of the signal to describe the data in domains of High frequency (HF), low frequency (LF), very low frequency (VLF) and LF/HF ratio. b) The quantified measurements of heart rate variables are then compared between different genotypes of candidate genes or different alleles of single nucleotide polymorphisms evenly distributed throughout the genome in an unbiased genome-wide approach.

Analysis of heart rate variability may provide valuable insights in a variety of settings.(53) Multiple studies have suggested that decreased heart rate variability may predict worsened outcomes in patients with congestive heart failure or after acute myocardial infarction.(54) Frequency-domain measures of HRV predict dysrhythmias in both ambulatory patients(16, 55) and patients after major thoracic surgery.(56) In patients with chronic pain(57) and chronic headaches,(58) frequency-domain measures of HRV suggest decreased vagal function compared to healthy controls. Additionally, reduced heart rate complexity is predictive of mortality in both critically ill patients(59) and trauma patients, regardless of injury mechanism.(60) Interestingly, gender and ethnic differences exist in frequency-domain measures of HRV,(61) though the genetic underpinnings of these differences remain unclear.

Another tool used to assess baroreceptor sensitivity is heart rate turbulence, which measures the variability in the beat-to-beat duration following a single premature ventricular beat.(62) This variable is thought to reflect the reflex activation of the vagus nerve to control sinus rhythm.(63) Several studies have associated heart rate turbulence with morbidity from cardiovascular diseases.(64, 65) This could partially be due to differences in intrinsic cardiac innervation during electrical remodeling of diseased myocardium, as well as mediated via autonomic influences on ion channels contributing to arrhythmogenesis. (62)

1. Heritability of HRV

A sub-study of the Framingham heart study found a higher correlation in several measurements of HRV between siblings than spouses of individuals included in the study, indicating a genetic contribution to the parameter. (17) Similarly, the twins heart study found that there was a higher correlation between indices of HRV between monozygous twins than heterozygous twins.(66) Ambulatory HRV, assessed at four periods in the day by SDNN and RMSSD from 24h ECG measurements, has also been compared between monozygous twins and dizygous twins/singleton siblings in a study of 772 individuals.(67) The genetic contribution to ambulatory HRV ranged from 35% to 48%. Recently the heritability of multiple indices of HRV (HR, SDNN, RMSSD, pNN50, LF, HF, LF/HF) was assessed in a large sample of 1060 adult twins, revealing that heritability explained approximately 50–60% of the variability of all HRV measurements performed.(68) This indicates that a portion of inter-individual variability in HRV is mediated by shared genome rather than shared environment.

2. Candidate Gene Approaches

Several studies have attempted to associate variants in individual genes or regions with measurements of HRV, mostly variants within the acetylcholinergic pathway. A study identified an association between a variant in the choline transporter gene (SLC5A7) and HRV assessed by both LF power and LF/HF ratio.(69) Variants in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were associated with both HF power and LF/HF ratio in a sample of 211 Chinese Han individuals. (70) The largest study to date combined genetic and HRV information for 6740 individuals from 7 smaller studies into discovery and replication cohorts and then tested for association of 443 variants within genes related to acetylcholine pathway (CHAT, SLC18A3, SLC5A7, CHRNB4, CHRNA3, CHRNA, CHRM2 and ACHE) and measurements of HRV assessed by RMSSD.(71) After correcting for multiple testing, no variant was found to be associated with HRV. The authors suggested that even though acetylcholine pathways might be involved in the physiology of HRV, their epigenetic interactions with other pathways controlled by other genes might not be fully understood. Identifying genes and pathways associated with HRV therefore likely requires an unbiased high-resolution genome-wide approach in an adequately powered cohort with high quality HRV phenotypes coupled with new and emerging bioinformatic and statistical procedures that permit the examination of gene-gene interactions.

3. Genome-wide association studies

The first attempted genome wide scan for HRV-associated traits was a linkage scan of individuals from the Framingham Heart Study, associating genetic regions with measurements of HRV (VLF power, LF power and HF power).(72) This identified two genetic regions on chromosomes 2 and 15. The region on chromosome 15 is in proximity with a cluster of genes coding for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. However, a follow-up 100 kb SNP resolution genome-wide scan of HRV (assessed by LF/HF power and total power) did not identify any variants associated with HRV in a cohort of 548 individuals from the offspring substudy of the Framingham study.(73) A recent meta-analysis utilizing 17 genome-wide association studies assessed the genetic contribution to HRV.(74) This was done mostly through studies measuring inter-beat interval variability (SDNN and RMSSD) on short or ultra-short (10 second) ECGs, although these variability measurements are more traditionally done on ECG measurements of longer duration. This study identified that genetic risk scores by combination of risk alleles only predicted 0.9–2.6% of the variability in these measurement, but also identified 8 loci with genome-wide associations. As expected there was a strong association between these measurements of HRV and heart rate, and several loci associated with heart rate were identified. These include pathways affecting acetylcholine release in the sinoatrial node and genes coding for muscarinic adrenergic potassium channels (GIRK).(74)

4. Lessons from monogenic diseases affecting cardiovascular tone

Several monogenic diseases have shed light on potential mechanisms affecting cardiovascular presentation of autonomic tone. Patients with dopamine beta-hydroxylase deficiency suffer from severe orthostatic hypotension in addition to other symptoms of lack of sympathetic tone, such as hypothermia.(75) The disease is due to mutations in the dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) gene responsible for conversion of dopamine to norepinephrine.(75) Similarly, patients with mutations in the norepinephrine-transporter gene (NET/SLC6A2) impairing the reuptake of norephinephrine into the releasing neuron. This results in increased activity and spillage of norepinephrine into circulation, resulting in elevated baseline heart rate and a profound response to orthostatic challenge.(76) Pathogenic mutations affecting the expression or increased copy numbers of the Parkinson disease 1 or 4 gene (SNCA, PARK1, PARK4) result in abnormally high expression of the alpha-synuclein protein, interacting with dopamine metabolism and affecting downstream generation of noradrenaline. In addition to causing early-onset Parkinsons disease, these patients will frequently have dysregulation in peripheral adrenergic receptors and symptoms of severe orthostatic hypotension.(77) These diseases all highlight the importance of metabolism of adrenergic neurotransmitters in modulating autonomic cardiovascular tone.

4. Autonomic Response to Physical Stress

a. Heritability of autonomic response to physical stress

Compared to the available data on heritability and the genetic background of HR, BP and HRV, less is known about the response to physical stressors. Several studies have tested the heritability of blood pressure response to orthostatic challenge, such as a head-up table tilting, is the most commonly applied physical stress. The heritability of blood pressure response to head-up table test was compared in a cohort of 444 individuals from five multi-generational families.(38) Heritability was assumed to explain about 14–19% of the variability in the DBP and SBP response to the head-up table test. Similarly, heritability was estimated to explain 25% of the change in SBP from an orthostatic challenge in a cohort of 767 families.(78) A total of 40% of the variability in HR change in response to cold pressor test was found to be heritable in a study of 576 individuals from twin and sibling pairs.(79) Another study found that 12–25% of the blood pressure response to cold pressor test was due to genetic effects in a family cohort of 835 individuals.(80)

b. Candidate gene studies of autonomic response to physical stress

In a cohort of 3630 untreated hypertensive patients, individuals homozygous for the Arg389/Gly variant in the beta-1 adrenergic receptor were found to have a greater change in SBP following an orthostatic challenge.(81) Polymorphisms in GNAS1, another gene in the sympathetic nervous system, were also found to be associated with differential response to orthostatic challenge in a cohort of 415 individuals.(82) No association was found with variants within genes involved in the renin-angiotension-aldosterone pathway. A weak association between orthostatism and a variant in the NEDD4L gene, that regulates expression of a sodium channel in the kidney, was also found in a study of 793 individuals.(83) Variants in the EBF1 and CYP17A1 genes were associated with a diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension in a study that tested the association of 31 variants associated with blood pressure or hypertension in genome-wide analysis in cohort of 38,970 individuals from 5 populations.(84) Multiple variants within sympathetic pathway have been associated with differential response to the cold pressor test (Table 2). Amongst those are variants in the CYB561 gene, a transporter gene in the sympathetic pathway,(79) as well as variants in the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) gene, involved in catecholamine biosynthesis.(85) Polymorphism in the beta-2 adrenergic receptor was also associated with the blood pressure response in a cohort of young twins.(86) Furthermore genes involved in intracellular signal transduction and its response to salt load, namely ADD1 and GNB3, and in genes (AGT, AGTR1) within renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway were also associated with the response to the cold pressor test in a Chinese Han population.(87, 88)

c. Genome-wide association studies of autonomic response to physical stress

A genome-wide study of changes in hypertension with orthostatic challenge in two Korean populations totaling approximately 6000 individuals identified multiple variants within the CTNNA2 gene, previously unassociated with any autonomic phenotypes, and changes in SBP.(89) Variants in PIK3AP1 were also associated with changes in SBP, and variants in ACTBL2, STAR and MYLK4 were associated with changes in DBP. None of these variants have been previously associated with autonomic tone. No variant was associated with a diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension. A genome-wide linkage study followed by single nucleotide polymorphism screen of linked regions identified variants in the MCM8, SLC23A2 and STK35 genes associated with the blood pressure response to the cold pressor test, via unknown pathways.(90)

5. Autonomic Response to Mental Stress

The heritability of the hemodynamic response to mental stressors has been assessed. In addition to baseline measurements, heritability was found to explain 44–74% of the HR and BP response to both a reaction time task and calculation task in a twin study with 373 twin pairs.(20) Another study found no significant increase in heritability in the response of HF and RMSSD measurements of HRV when 735 twin pairs were exposed to virtual reality driving stressor, video game or a social competence interview. This indicates that the same genes regulate the HRV under rest and stress.(91) However, a subset of the individuals also underwent 24h blood pressure measurement to assess hemodynamic response to real-life stressors. This indicated that a substantial fraction of the variability in hemodynamic response was unexplained by genes explaining baseline HRV.(92) Thus far, no candidate gene studies or genome-wide association studies on the hemodynamic effects of mental stress exist.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Autonomic tone is a paramount physiological variable associated with multiple cardiovascular outcomes of clinical interest. Cardiovascular measures of autonomic tone involve both basic measurements of the static components such as heart rate and blood pressure as well as more complex measurements of the dynamic components of autonomic tone such as different spectra of heart rate variability. Furthermore, the effects of physiological and psychological strain on these measurements can be quantified.

Both the heritability and genetic background of the static aspects of cardiovascular measurements of autonomic tone, such as resting heart rate and blood pressure, have been thoroughly studied. As highlighted here, this has revealed a substantial genetic component of these static variables, both when studied macroscopically by shared variability between twins and in high-resolution genome-wide association studies. Interestingly, there is no overlap where associations between these measurements and plausible candidate genes identified via candidate gene studies have not been identified or confirmed in a hypothesis-free genome-wide association studies. Furthermore, the identified variants generally did not conform to a single cellular signaling or metabolic pathway. This indicates that there is likely a multifactorial genetic contribution to these variables.

Furthermore, heritability represents a large component of the variability in measurements of the dynamic phase of autonomic tone, namely heart rate variability and changes in heart rate, blood pressure and heart rate variability with physical and psychological stressors. However, there is currently a lack of high-resolution genome-wide association studies with a high-quality phenotyping of these important variables. Furthermore, novel bioinformatical methods, such as functional group/pathway analysis and modeling of polygenic effects, should be applied to the results of genome-wide association analyses to reveal effects that are not able to pass conservative significance thresholds typically applied to the genome-wide analyses. Comprehensive functional annotation of genetic variants via bioinformatic databases (such as tissue-specific gene expression and DNA methylation maps) is needed to understand how identified variants mediate their biological effects. Finally, limited work exists on modification of autonomic tone to affect the associated cardiovascular outcomes. These could include heart rate modulation by blockade of beta-receptor or calcium channels. It is likely that only a subset of the patients would have benefit from such interventions, and perhaps these patients could be identified in the future from their genetic background. It is likely that such studies will follow, given the utility of such information for cardiovascular risk prognostication and development of novel therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (grants U01-DE017018; WM and P01NS045685;WM). NHW is supported by an American Heart Association Mentored Clinical and Population Research Award (16MCPRP30700010).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Maixner and Smith have equity ownership in Algynomics Inc. Dr. Maixner is a on a patent application related to COMT haplotypes and pain sensitivity, which has been licensed to Proove Biosciences. Dr. Maixner is also on the Board of Directors of Orthogen Inc. These relationships have been reviewed in conjunction with this research and are under management by the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill and Duke University.

References

- 1.Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex. Nature. 2002 Dec 19–26;420(6917):853–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2009 Jun;10(6):397–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuroscience. 2. Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Floras JS, Ponikowski P. The sympathetic/parasympathetic imbalance in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. European heart journal. 2015 Aug 07;36(30):1974–82b. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grassi G, Ram VS. Evidence for a critical role of the sympathetic nervous system in hypertension. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension : JASH. 2016 May;10(5):457–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen MJ, Zipes DP. Role of the autonomic nervous system in modulating cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation research. 2014 Mar 14;114(6):1004–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalla M, Herring N, Paterson DJ. Cardiac sympatho-vagal balance and ventricular arrhythmia. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical. 2016 Aug;199:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin BY, Anderson SL. The molecular basis of familial dysautonomia: overview, new discoveries and implications for directed therapies. Neuromolecular medicine. 2008;10(3):148–56. doi: 10.1007/s12017-007-8019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taggart P, Critchley H, van Duijvendoden S, Lambiase PD. Significance of neuro-cardiac control mechanisms governed by higher regions of the brain. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical. 2016 Aug;199:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verrier RL, Tan A. Heart rate, autonomic markers, and cardiac mortality. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2009 Nov;6(11 Suppl):S68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, Danchin N, Ferrari R, Lopez Sendon JL, Steg PG, Tardif JC, Tavazzi L, Tendera M, Heart Rate Working G Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007 Aug 28;50(9):823–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opdahl A, Ambale Venkatesh B, Fernandes VR, Wu CO, Nasir K, Choi EY, Almeida AL, Rosen B, Carvalho B, Edvardsen T, Bluemke DA, Lima JA. Resting heart rate as predictor for left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Apr 01;63(12):1182–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li K, Yao C, Yang X, Dong L. Effect of Resting Heart Rate on All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events According to Age. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016 Dec 30; doi: 10.1111/jgs.14714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenspan JD, Slade GD, Bair E, Dubner R, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Knott C, Diatchenko L, Liu Q, Maixner W. Pain sensitivity and autonomic factors associated with development of TMD: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2013 Dec;14(12 Suppl):T63–74. e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maixner W, Greenspan JD, Dubner R, Bair E, Mulkey F, Miller V, Knott C, Slade GD, Ohrbach R, Diatchenko L, Fillingim RB. Potential autonomic risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2011 Nov;12(11 Suppl):T75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal SK, Norby FL, Whitsel EA, Soliman EZ, Chen LY, Loehr LR, Fuster V, Heiss G, Coresh J, Alonso A. Cardiac Autonomic Dysfunction and Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation: Results From 20 Years Follow-Up. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Jan 24;69(3):291–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh JP, Larson MG, O'Donnell CJ, Tsuji H, Evans JC, Levy D. Heritability of heart rate variability: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1999 May 04;99(17):2251–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.17.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranade K, Jorgenson E, Sheu WH, Pei D, Hsiung CA, Chiang FT, Chen YD, Pratt R, Olshen RA, Curb D, Cox DR, Botstein D, Risch N. A polymorphism in the beta1 adrenergic receptor is associated with resting heart rate. Am J Hum Genet. 2002 Apr;70(4):935–42. doi: 10.1086/339621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell MW, Law I, Sholinsky P, Fabsitz RR. Heritability of ECG measurements in adult male twins. J Electrocardiol. 1998;30(Suppl):64–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(98)80034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Geus EJ, Kupper N, Boomsma DI, Snieder H. Bivariate genetic modeling of cardiovascular stress reactivity: does stress uncover genetic variance? Psychosom Med. 2007 May;69(4):356–64. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318049cc2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilk JB, Myers RH, Pankow JS, Hunt SC, Leppert MF, Freedman BI, Province MA, Ellison RC. Adrenergic receptor polymorphisms associated with resting heart rate: the HyperGEN Study. Ann Hum Genet. 2006 Sep;70(Pt 5):566–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2005.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ylitalo A, Airaksinen KE, Hautanen A, Kupari M, Carson M, Virolainen J, Savolainen M, Kauma H, Kesaniemi YA, White PC, Huikuri HV. Baroreflex sensitivity and variants of the renin angiotensin system genes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 Jan;35(1):194–200. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holm H, Gudbjartsson DF, Arnar DO, Thorleifsson G, Thorgeirsson G, Stefansdottir H, Gudjonsson SA, Jonasdottir A, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Nyrnes A, Wilsgaard T, Hald EM, Hveem K, Stoltenberg C, Lochen ML, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. Several common variants modulate heart rate, PR interval and QRS duration. Nat Genet. 2010 Feb;42(2):117–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.den Hoed M, Eijgelsheim M, Esko T, Brundel BJ, Peal DS, Evans DM, Nolte IM, Segre AV, Holm H, Handsaker RE, Westra HJ, Johnson T, Isaacs A, Yang J, Lundby A, Zhao JH, Kim YJ, Go MJ, Almgren P, Bochud M, Boucher G, Cornelis MC, Gudbjartsson D, Hadley D, van der Harst P, Hayward C, den Heijer M, Igl W, Jackson AU, Kutalik Z, Luan J, Kemp JP, Kristiansson K, Ladenvall C, Lorentzon M, Montasser ME, Njajou OT, O'Reilly PF, Padmanabhan S, St Pourcain B, Rankinen T, Salo P, Tanaka T, Timpson NJ, Vitart V, Waite L, Wheeler W, Zhang W, Draisma HH, Feitosa MF, Kerr KF, Lind PA, Mihailov E, Onland-Moret NC, Song C, Weedon MN, Xie W, Yengo L, Absher D, Albert CM, Alonso A, Arking DE, de Bakker PI, Balkau B, Barlassina C, Benaglio P, Bis JC, Bouatia-Naji N, Brage S, Chanock SJ, Chines PS, Chung M, Darbar D, Dina C, Dorr M, Elliott P, Felix SB, Fischer K, Fuchsberger C, de Geus EJ, Goyette P, Gudnason V, Harris TB, Hartikainen AL, Havulinna AS, Heckbert SR, Hicks AA, Hofman A, Holewijn S, Hoogstra-Berends F, Hottenga JJ, Jensen MK, Johansson A, Junttila J, Kaab S, Kanon B, Ketkar S, Khaw KT, Knowles JW, Kooner AS, Kors JA, Kumari M, Milani L, Laiho P, Lakatta EG, Langenberg C, Leusink M, Liu Y, Luben RN, Lunetta KL, Lynch SN, Markus MR, Marques-Vidal P, Leach IM, McArdle WL, McCarroll SA, Medland SE, Miller KA, Montgomery GW, Morrison AC, M MVL-N, Navarro P, Nelis M, O'Connell JR, O'Donnell CJ, Ong KK, Newman AB, Peters A, Polasek O, Pouta A, Pramstaller PP, Psaty BM, Rao DC, Ring SM, Rossin EJ, Rudan D, Sanna S, Scott RA, Sehmi JS, Sharp S, Shin JT, Singleton AB, Smith AV, Soranzo N, Spector TD, Stewart C, Stringham HM, Tarasov KV, Uitterlinden AG, Vandenput L, Hwang SJ, Whitfield JB, Wijmenga C, Wild SH, Willemsen G, Wilson JF, Witteman JC, Wong A, Wong Q, Jamshidi Y, Zitting P, Boer JM, Boomsma DI, Borecki IB, van Duijn CM, Ekelund U, Forouhi NG, Froguel P, Hingorani A, Ingelsson E, Kivimaki M, Kronmal RA, Kuh D, Lind L, Martin NG, Oostra BA, Pedersen NL, Quertermous T, Rotter JI, van der Schouw YT, Verschuren WM, Walker M, Albanes D, Arnar DO, Assimes TL, Bandinelli S, Boehnke M, de Boer RA, Bouchard C, Caulfield WL, Chambers JC, Curhan G, Cusi D, Eriksson J, Ferrucci L, van Gilst WH, Glorioso N, de Graaf J, Groop L, Gyllensten U, Hsueh WC, Hu FB, Huikuri HV, Hunter DJ, Iribarren C, Isomaa B, Jarvelin MR, Jula A, Kahonen M, Kiemeney LA, van der Klauw MM, Kooner JS, Kraft P, Iacoviello L, Lehtimaki T, Lokki ML, Mitchell BD, Navis G, Nieminen MS, Ohlsson C, Poulter NR, Qi L, Raitakari OT, Rimm EB, Rioux JD, Rizzi F, Rudan I, Salomaa V, Sever PS, Shields DC, Shuldiner AR, Sinisalo J, Stanton AV, Stolk RP, Strachan DP, Tardif JC, Thorsteinsdottir U, Tuomilehto J, van Veldhuisen DJ, Virtamo J, Viikari J, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Widen E, Cho YS, Olsen JV, Visscher PM, Willer C, Franke L, Erdmann J, Thompson JR, Pfeufer A, Sotoodehnia N, Newton-Cheh C, Ellinor PT, Stricker BH, Metspalu A, Perola M, Beckmann JS, Smith GD, Stefansson K, Wareham NJ, Munroe PB, Sibon OC, Milan DJ, Snieder H, Samani NJ, Loos RJ. Identification of heart rate-associated loci and their effects on cardiac conduction and rhythm disorders. Nat Genet. 2013 Apr 14; doi: 10.1038/ng.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eppinga RN, Hagemeijer Y, Burgess S, Hinds DA, Stefansson K, Gudbjartsson DF, van Veldhuisen DJ, Munroe PB, Verweij N, van der Harst P. Identification of genomic loci associated with resting heart rate and shared genetic predictors with all-cause mortality. Nat Genet. 2016 Dec;48(12):1557–63. doi: 10.1038/ng.3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salman IM. Major Autonomic Neuroregulatory Pathways Underlying Short- and Long-Term Control of Cardiovascular Function. Current hypertension reports. 2016 Mar;18(3):18. doi: 10.1007/s11906-016-0625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Victor RG. Carotid baroreflex activation therapy for resistant hypertension. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2015 Aug;12(8):451–63. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonell KE, Shibao CA, Claassen DO. Clinical Relevance of Orthostatic Hypotension in Neurodegenerative Disease. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2015 Dec;15(12):78. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mancia G, Grassi G. The autonomic nervous system and hypertension. Circulation research. 2014 May 23;114(11):1804–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Mancia G. Sympathetic activation in cardiovascular disease: evidence, clinical impact and therapeutic implications. European journal of clinical investigation. 2015 Dec;45(12):1367–75. doi: 10.1111/eci.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xin W, Lin Z, Mi S. Orthostatic hypotension and mortality risk: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Heart. 2014 Mar;100(5):406–13. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barlow PA, Otahal P, Schultz MG, Shing CM, Sharman JE. Low exercise blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2014 Nov;237(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coffman TM. Under pressure: the search for the essential mechanisms of hypertension. Nature medicine. 2011 Nov 07;17(11):1402–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC, Jr, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT, Jr, Narva AS, Ortiz E. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) Jama. 2014 Feb 05;311(5):507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yusuf S, Lonn E. The SPRINT and the HOPE-3 Trial in the Context of Other Blood Pressure-Lowering Trials. JAMA cardiology. 2016 Nov 01;1(8):857–8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherwood A, Hill LK, Blumenthal JA, Johnson KS, Hinderliter AL. Race and sex differences in cardiovascular alpha-adrenergic and beta-adrenergic receptor responsiveness in men and women with high blood pressure. Journal of hypertension. 2017 May;35(5):975–81. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salfati E, Morrison AC, Boerwinkle E, Chakravarti A. Direct Estimates of the Genomic Contributions to Blood Pressure Heritability within a Population-Based Cohort (ARIC) PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choh AC, Czerwinski SA, Lee M, Demerath EW, Cole SA, Wilson AF, Towne B, Siervogel RM. Quantitative genetic analysis of blood pressure reactivity to orthostatic tilt using principal components analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2006 Apr;20(4):281–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seasholtz TM, Wessel J, Rao F, Rana BK, Khandrika S, Kennedy BP, Lillie EO, Ziegler MG, Smith DW, Schork NJ, Brown JH, O'Connor DT. Rho kinase polymorphism influences blood pressure and systemic vascular resistance in human twins: role of heredity. Hypertension. 2006 May;47(5):937–47. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217364.45622.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tank J, Jordan J, Diedrich A, Stoffels M, Franke G, Faulhaber HD, Luft FC, Busjahn A. Genetic influences on baroreflex function in normal twins. Hypertension. 2001 Mar;37(3):907–10. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.3.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ji W, Foo JN, O'Roak BJ, Zhao H, Larson MG, Simon DB, Newton-Cheh C, State MW, Levy D, Lifton RP. Rare independent mutations in renal salt handling genes contribute to blood pressure variation. Nat Genet. 2008 May;40(5):592–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sober S, Org E, Kepp K, Juhanson P, Eyheramendy S, Gieger C, Lichtner P, Klopp N, Veldre G, Viigimaa M, Doring A, Kooperative Gesundheitsforschung in der Region Augsburg S. Putku M, Kelgo P, Study HYiE. Shaw-Hawkins S, Howard P, Onipinla A, Dobson RJ, Newhouse SJ, Brown M, Dominiczak A, Connell J, Samani N, Farrall M, Study MRCBGoH. Caulfield MJ, Munroe PB, Illig T, Wichmann HE, Meitinger T, Laan M. Targeting 160 candidate genes for blood pressure regulation with a genome-wide genotyping array. PLoS One. 2009 Jun 29;4(6):e6034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xing-Sheng Y, Yong-Zhi L, Jie-Xin L, Yu-Qing G, Zhang-Huang C, Chong-Fa Z, Zhi-Zhong T, Shu-Zheng L. Genetic influence on baroreflex sensitivity in normotensive young men. Am J Hypertens. 2010 Jun;23(6):655–9. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wellcome Trust Case Control C. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007 Jun 07;447(7145):661–78. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehret GB, Ferreira T, Chasman DI, Jackson AU, Schmidt EM, Johnson T, Thorleifsson G, Luan J, Donnelly LA, Kanoni S, Petersen AK, Pihur V, Strawbridge RJ, Shungin D, Hughes MF, Meirelles O, Kaakinen M, Bouatia-Naji N, Kristiansson K, Shah S, Kleber ME, Guo X, Lyytikainen LP, Fava C, Eriksson N, Nolte IM, Magnusson PK, Salfati EL, Rallidis LS, Theusch E, Smith AJ, Folkersen L, Witkowska K, Pers TH, Joehanes R, Kim SK, Lataniotis L, Jansen R, Johnson AD, Warren H, Kim YJ, Zhao W, Wu Y, Tayo BO, Bochud M, Consortium CH-E, Consortium C-H, Wellcome Trust Case Control C. Absher D, Adair LS, Amin N, Arking DE, Axelsson T, Baldassarre D, Balkau B, Bandinelli S, Barnes MR, Barroso I, Bevan S, Bis JC, Bjornsdottir G, Boehnke M, Boerwinkle E, Bonnycastle LL, Boomsma DI, Bornstein SR, Brown MJ, Burnier M, Cabrera CP, Chambers JC, Chang IS, Cheng CY, Chines PS, Chung RH, Collins FS, Connell JM, Doring A, Dallongeville J, Danesh J, de Faire U, Delgado G, Dominiczak AF, Doney AS, Drenos F, Edkins S, Eicher JD, Elosua R, Enroth S, Erdmann J, Eriksson P, Esko T, Evangelou E, Evans A, Fall T, Farrall M, Felix JF, Ferrieres J, Ferrucci L, Fornage M, Forrester T, Franceschini N, Franco OH, Franco-Cereceda A, Fraser RM, Ganesh SK, Gao H, Gertow K, Gianfagna F, Gigante B, Giulianini F, Goel A, Goodall AH, Goodarzi MO, Gorski M, Grassler J, Groves CJ, Gudnason V, Gyllensten U, Hallmans G, Hartikainen AL, Hassinen M, Havulinna AS, Hayward C, Hercberg S, Herzig KH, Hicks AA, Hingorani AD, Hirschhorn JN, Hofman A, Holmen J, Holmen OL, Hottenga JJ, Howard P, Hsiung CA, Hunt SC, Ikram MA, Illig T, Iribarren C, Jensen RA, Kahonen M, Kang HM, Kathiresan S, Keating BJ, Khaw KT, Kim YK, Kim E, Kivimaki M, Klopp N, Kolovou G, Komulainen P, Kooner JS, Kosova G, Krauss RM, Kuh D, Kutalik Z, Kuusisto J, Kvaloy K, Lakka TA, Lee NR, Lee IT, Lee WJ, Levy D, Li X, Liang KW, Lin H, Lin L, Lindstrom J, Lobbens S, Mannisto S, Muller G, Muller-Nurasyid M, Mach F, Markus HS, Marouli E, McCarthy MI, McKenzie CA, Meneton P, Menni C, Metspalu A, Mijatovic V, Moilanen L, Montasser ME, Morris AD, Morrison AC, Mulas A, Nagaraja R, Narisu N, Nikus K, O'Donnell CJ, O'Reilly PF, Ong KK, Paccaud F, Palmer CD, Parsa A, Pedersen NL, Penninx BW, Perola M, Peters A, Poulter N, Pramstaller PP, Psaty BM, Quertermous T, Rao DC, Rasheed A, Rayner NW, Renstrom F, Rettig R, Rice KM, Roberts R, Rose LM, Rossouw J, Samani NJ, Sanna S, Saramies J, Schunkert H, Sebert S, Sheu WH, Shin YA, Sim X, Smit JH, Smith AV, Sosa MX, Spector TD, Stancakova A, Stanton AV, Stirrups KE, Stringham HM, Sundstrom J, Swift AJ, Syvanen AC, Tai ES, Tanaka T, Tarasov KV, Teumer A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Tobin MD, Tremoli E, Uitterlinden AG, Uusitupa M, Vaez A, Vaidya D, van Duijn CM, van Iperen EP, Vasan RS, Verwoert GC, Virtamo J, Vitart V, Voight BF, Vollenweider P, Wagner A, Wain LV, Wareham NJ, Watkins H, Weder AB, Westra HJ, Wilks R, Wilsgaard T, Wilson JF, Wong TY, Yang TP, Yao J, Yengo L, Zhang W, Zhao JH, Zhu X, Bovet P, Cooper RS, Mohlke KL, Saleheen D, Lee JY, Elliott P, Gierman HJ, Willer CJ, Franke L, Hovingh GK, Taylor KD, Dedoussis G, Sever P, Wong A, Lind L, Assimes TL, Njolstad I, Schwarz PE, Langenberg C, Snieder H, Caulfield MJ, Melander O, Laakso M, Saltevo J, Rauramaa R, Tuomilehto J, Ingelsson E, Lehtimaki T, Hveem K, Palmas W, Marz W, Kumari M, Salomaa V, Chen YD, Rotter JI, Froguel P, Jarvelin MR, Lakatta EG, Kuulasmaa K, Franks PW, Hamsten A, Wichmann HE, Palmer CN, Stefansson K, Ridker PM, Loos RJ, Chakravarti A, Deloukas P, Morris AP, Newton-Cheh C, Munroe PB. The genetics of blood pressure regulation and its target organs from association studies in 342,415 individuals. Nat Genet. 2016 Oct;48(10):1171–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K, Verwoert GC, Launer LJ, Dehghan A, Glazer NL, Morrison AC, Johnson AD, Aspelund T, Aulchenko Y, Lumley T, Kottgen A, Vasan RS, Rivadeneira F, Eiriksdottir G, Guo X, Arking DE, Mitchell GF, Mattace-Raso FU, Smith AV, Taylor K, Scharpf RB, Hwang SJ, Sijbrands EJ, Bis J, Harris TB, Ganesh SK, O'Donnell CJ, Hofman A, Rotter JI, Coresh J, Benjamin EJ, Uitterlinden AG, Heiss G, Fox CS, Witteman JC, Boerwinkle E, Wang TJ, Gudnason V, Larson MG, Chakravarti A, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet. 2009 Jun;41(6):677–87. doi: 10.1038/ng.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Padmanabhan S, Caulfield M, Dominiczak AF. Genetic and molecular aspects of hypertension. Circ Res. 2015 Mar 13;116(6):937–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 1996 Mar 1;93(5):1043–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sassi R, Cerutti S, Lombardi F, Malik M, Huikuri HV, Peng CK, Schmidt G, Yamamoto Y. Advances in heart rate variability signal analysis: joint position statement by the e-Cardiology ESC Working Group and the European Heart Rhythm Association co-endorsed by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2015 Sep;17(9):1341–53. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohira H, Matsunaga M, Osumi T, Fukuyama S, Shinoda J, Yamada J, Gidron Y. Vagal nerve activity as a moderator of brain-immune relationships. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2013 Jul 15;260(1–2):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eller NH. Total power and high frequency components of heart rate variability and risk factors for atherosclerosis. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical. 2007 Jan 30;131(1–2):123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baumert M, Lambert GW, Dawood T, Lambert EA, Esler MD, McGrane M, Barton D, Sanders P, Nalivaiko E. Short-term heart rate variability and cardiac norepinephrine spillover in patients with depression and panic disorder. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2009 Aug;297(2):H674–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00236.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mazzeo AT, La Monaca E, Di Leo R, Vita G, Santamaria LB. Heart rate variability: a diagnostic and prognostic tool in anesthesia and intensive care. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2011 Aug;55(7):797–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huikuri HV, Stein PK. Heart rate variability in risk stratification of cardiac patients. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2013 Sep-Oct;56(2):153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bettoni M, Zimmermann M. Autonomic tone variations before the onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2002 Jun 11;105(23):2753–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018443.44005.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amar D, Zhang H, Miodownik S, Kadish AH. Competing autonomic mechanisms precede the onset of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003 Oct 1;42(7):1262–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00955-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koenig J, Falvay D, Clamor A, Wagner J, Jarczok MN, Ellis RJ, Weber C, Thayer JF. Pneumogastric (Vagus) Nerve Activity Indexed by Heart Rate Variability in Chronic Pain Patients Compared to Healthy Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain physician. 2016 Jan;19(1):E55–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koenig J, Williams DP, Kemp AH, Thayer JF. Vagally mediated heart rate variability in headache patients--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2016 Mar;36(3):265–78. doi: 10.1177/0333102415583989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Norris PR, Stein PK, Morris JA., Jr Reduced heart rate multiscale entropy predicts death in critical illness: a study of physiologic complexity in 285 trauma patients. Journal of critical care. 2008 Sep;23(3):399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riordan WP, Jr, Norris PR, Jenkins JM, Morris JA., Jr Early loss of heart rate complexity predicts mortality regardless of mechanism, anatomic location, or severity of injury in 2178 trauma patients. The Journal of surgical research. 2009 Oct;156(2):283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, Thayer JF, Treiber F, Snieder H. Ethnic differences and heritability of heart rate variability in African- and European American youth. The American journal of cardiology. 2005 Oct 15;96(8):1166–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verrier RL, Antzelevitch C. Autonomic aspects of arrhythmogenesis: the enduring and the new. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004 Jan;19(1):2–11. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guzik P, Schmidt G. A phenomenon of heart-rate turbulence, its evaluation, and prognostic value. Card Electrophysiol Rev. 2002 Sep;6(3):256–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1016333109829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmidt G, Malik M, Barthel P, Schneider R, Ulm K, Rolnitzky L, Camm AJ, Bigger JT, Jr, Schomig A. Heart-rate turbulence after ventricular premature beats as a predictor of mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1999 Apr 24;353(9162):1390–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.La Rovere MT, Bigger JT, Jr, Marcus FI, Mortara A, Schwartz PJ. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction) Investigators. Lancet. 1998 Feb 14;351(9101):478–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Su S, Lampert R, Lee F, Bremner JD, Snieder H, Jones L, Murrah NV, Goldberg J, Vaccarino V. Common genes contribute to depressive symptoms and heart rate variability: the Twins Heart Study. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2010 Feb;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.1375/twin.13.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kupper NH, Willemsen G, van den Berg M, de Boer D, Posthuma D, Boomsma DI, de Geus EJ. Heritability of ambulatory heart rate variability. Circulation. 2004 Nov 02;110(18):2792–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146334.96820.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Golosheykin S, Grant JD, Novak OV, Heath AC, Anokhin AP. Genetic influences on heart rate variability. Int J Psychophysiol. 2016 Apr 22; doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neumann SA, Lawrence EC, Jennings JR, Ferrell RE, Manuck SB. Heart rate variability is associated with polymorphic variation in the choline transporter gene. Psychosom Med. 2005 Mar-Apr;67(2):168–71. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000155671.90861.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang AC, Chen TJ, Tsai SJ, Hong CJ, Kuo CH, Yang CH, Kao KP. BDNF Val66Met polymorphism alters sympathovagal balance in healthy subjects. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010 Jul;153B(5):1024–30. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riese H, Munoz LM, Hartman CA, Ding X, Su S, Oldehinkel AJ, van Roon AM, van der Most PJ, Lefrandt J, Gansevoort RT, van der Harst P, Verweij N, Licht CM, Boomsma DI, Hottenga JJ, Willemsen G, Penninx BW, Nolte IM, de Geus EJ, Wang X, Snieder H. Identifying genetic variants for heart rate variability in the acetylcholine pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh JP, Larson MG, O'Donnell CJ, Tsuji H, Corey D, Levy D. Genome scan linkage results for heart rate variability (the Framingham Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 2002 Dec 15;90(12):1290–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02865-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Newton-Cheh C, Guo CY, Wang TJ, O'Donnell CJ, Levy D, Larson MG. Genome-wide association study of electrocardiographic and heart rate variability traits: the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007 Sep 19;8(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nolte IM, Munoz ML, Tragante V, Amare AT, Jansen R, Vaez A, von der Heyde B, Avery CL, Bis JC, Dierckx B, van Dongen J, Gogarten SM, Goyette P, Hernesniemi J, Huikari V, Hwang SJ, Jaju D, Kerr KF, Kluttig A, Krijthe BP, Kumar J, van der Laan SW, Lyytikainen LP, Maihofer AX, Minassian A, van der Most PJ, Muller-Nurasyid M, Nivard M, Salvi E, Stewart JD, Thayer JF, Verweij N, Wong A, Zabaneh D, Zafarmand MH, Abdellaoui A, Albarwani S, Albert C, Alonso A, Ashar F, Auvinen J, Axelsson T, Baker DG, de Bakker PIW, Barcella M, Bayoumi R, Bieringa RJ, Boomsma D, Boucher G, Britton AR, Christophersen I, Dietrich A, Ehret GB, Ellinor PT, Eskola M, Felix JF, Floras JS, Franco OH, Friberg P, Gademan MGJ, Geyer MA, Giedraitis V, Hartman CA, Hemerich D, Hofman A, Hottenga JJ, Huikuri H, Hutri-Kahonen N, Jouven X, Junttila J, Juonala M, Kiviniemi AM, Kors JA, Kumari M, Kuznetsova T, Laurie CC, Lefrandt JD, Li Y, Li Y, Liao D, Limacher MC, Lin HJ, Lindgren CM, Lubitz SA, Mahajan A, McKnight B, Zu Schwabedissen HM, Milaneschi Y, Mononen N, Morris AP, Nalls MA, Navis G, Neijts M, Nikus K, North KE, O'Connor DT, Ormel J, Perz S, Peters A, Psaty BM, Raitakari OT, Risbrough VB, Sinner MF, Siscovick D, Smit JH, Smith NL, Soliman EZ, Sotoodehnia N, Staessen JA, Stein PK, Stilp AM, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Strauch K, Sundstrom J, Swenne CA, Syvanen AC, Tardif JC, Taylor KD, Teumer A, Thornton TA, Tinker LE, Uitterlinden AG, van Setten J, Voss A, Waldenberger M, Wilhelmsen KC, Willemsen G, Wong Q, Zhang ZM, Zonderman AB, Cusi D, Evans MK, Greiser HK, van der Harst P, Hassan M, Ingelsson E, Jarvelin MR, Kaab S, Kahonen M, Kivimaki M, Kooperberg C, Kuh D, Lehtimaki T, Lind L, Nievergelt CM, O'Donnell CJ, Oldehinkel AJ, Penninx B, Reiner AP, Riese H, van Roon AM, Rioux JD, Rotter JI, Sofer T, Stricker BH, Tiemeier H, Vrijkotte TGM, Asselbergs FW, Brundel B, Heckbert SR, Whitsel EA, den Hoed M, Snieder H, de Geus EJC. Genetic loci associated with heart rate variability and their effects on cardiac disease risk. Nature communications. 2017 Jun 14;8:15805. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Senard JM, Rouet P. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006 Mar 30;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shannon JR, Flattem NL, Jordan J, Jacob G, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Blakely RD, Robertson D. Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine-transporter deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 24;342(8):541–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oczkowska A, Kozubski W, Lianeri M, Dorszewska J. Mutations in PRKN and SNCA Genes Important for the Progress of Parkinson's Disease. Curr Genomics. 2013 Dec;14(8):502–17. doi: 10.2174/1389202914666131210205839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harrap SB, Cui JS, Wong ZY, Hopper JL. Familial and genomic analyses of postural changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Hypertension. 2004 Mar;43(3):586–91. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000118044.84189.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang K, Deacon DC, Rao F, Schork AJ, Fung MM, Waalen J, Schork NJ, Nievergelt CM, Chi NC, O'Connor DT. Human heart rate: heritability of resting and stress values in twin pairs, and influence of genetic variation in the adrenergic pathway at a microribonucleic acid (microrna) motif in the 3'-UTR of cytochrome b561 [corrected] J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Feb 04;63(4):358–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roy-Gagnon MH, Weir MR, Sorkin JD, Ryan KA, Sack PA, Hines S, Bielak LF, Peyser PA, Post W, Mitchell BD, Shuldiner AR, Douglas JA. Genetic influences on blood pressure response to the cold pressor test: results from the Heredity and Phenotype Intervention Heart Study. J Hypertens. 2008 Apr;26(4):729–36. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f524b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gao Y, Lin Y, Sun K, Wang Y, Chen J, Wang H, Zhou X, Fan X, Hui R. Orthostatic blood pressure dysregulation and polymorphisms of beta-adrenergic receptor genes in hypertensive patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014 Mar;16(3):207–13. doi: 10.1111/jch.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tabara Y, Kohara K, Miki T. Polymorphisms of genes encoding components of the sympathetic nervous system but not the renin-angiotensin system as risk factors for orthostatic hypotension. J Hypertens. 2002 Apr;20(4):651–6. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200204000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luo F, Wang Y, Wang X, Sun K, Zhou X, Hui R. A functional variant of NEDD4L is associated with hypertension, antihypertensive response, and orthostatic hypotension. Hypertension. 2009 Oct;54(4):796–801. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fedorowski A, Franceschini N, Brody J, Liu C, Verwoert GC, Boerwinkle E, Couper D, Rice KM, Rotter JI, Mattace-Raso F, Uitterlinden A, Hofman A, Almgren P, Sjogren M, Hedblad B, Larson MG, Newton-Cheh C, Wang TJ, Rose KM, Psaty BM, Levy D, Witteman J, Melander O. Orthostatic hypotension and novel blood pressure-associated gene variants: Genetics of Postural Hemodynamics (GPH) Consortium. Eur Heart J. 2012 Sep;33(18):2331–41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rao F, Zhang L, Wessel J, Zhang K, Wen G, Kennedy BP, Rana BK, Das M, Rodriguez-Flores JL, Smith DW, Cadman PE, Salem RM, Mahata SK, Schork NJ, Taupenot L, Ziegler MG, O'Connor DT. Adrenergic polymorphism and the human stress response. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008 Dec;1148:282–96. doi: 10.1196/annals.1410.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li GH, Faulhaber HD, Rosenthal M, Schuster H, Jordan J, Timmermann B, Hoehe MR, Luft FC, Busjahn A. Beta-2 adrenergic receptor gene variations and blood pressure under stress in normal twins. Psychophysiology. 2001 May;38(3):485–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]