Recruitment and retention outcomes are indicators of intervention feasibility, a key implementation outcome suggestive of whether an intervention may be successfully utilized within a certain context [1]. Regardless of treatment efficacy, when the treatment cannot be reliably carried out within a particular healthcare system, the potential scale of intervention benefits to the population served is diminished. Unfortunately, rates of recruitment for studies of psychosocial interventions in oncology settings are known to be low, typically 50% to 60% [2]. This challenges not only the feasibility of conducting the early intervention efficacy studies, but also the likelihood of ultimate dissemination and implementation into standard practice.

Identifying obstacles to psycho-oncology interventions is important because most people treated for cancer experience distress or treatment-related side effects that can be effectively managed by these interventions. One such area is sexual dysfunction, which is common, distressing, and a key survivorship concern among men [3]. Treatments for rectal and anal cancers are particularly associated with sexual side effects, with up to half of male survivors reporting decreased libido and partial impotence [4]. Male survivors of rectal and anal cancers have expressed strong interest in treatments to address sexual problems [5], yet such interventions show even greater recruitment and retention difficulties than other psycho-oncology interventions [6-8].

The current study examines recruitment and retention for a sexual health intervention pilot for male rectal and anal cancer survivors. Identifying barriers to intervention feasibility will provide important information to improve study design and intervention implementation in the oncology context.

Methods

Eligibility criteria, research design, and recruitment strategy primarily matched that from the parallel pilot intervention study conducted among female rectal and anal cancer survivors (see [7,9]). Only facets unique to the men’s trial are reviewed here. This study was approved by the MSKCC Institutional Review Board (protocol #08-073).

Eligibility

In addition to medical and demographic eligibility criteria, men were required to endorse “moderate” or lower (≤3) confidence in their ability to achieve and maintain erections on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5 (very high confidence) to 1 (very low confidence). After noting a trend in which eligible and consented men randomized to the intervention condition often declined to participate due to lack of distress from their sexual functioning, an additional eligibility requirement was added. Men were henceforth only eligible if, in addition to all prior eligibility criteria, they also endorsed “a little” or more (≥2) bother related to their difficulty with erections on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all bothered) to 5 (extremely bothered).

Research design

This randomized controlled trial pilot study tested an intervention intended to reduce sexual dysfunction among rectal and anal cancer survivors compared to an information-only control. The intervention was tailored from a psycho-educational intervention for men with prostate cancer [6,10] based on expert clinical review. The modified intervention was assessed by focus groups of rectal cancer survivors [5]. The intervention comprised 4 one-hour sessions, with brief booster calls between sessions. Sessions were typically conducted by phone (80% vs. 20% in-person).

Differential attrition was noted. Men randomized to the intervention often declined to participate in the intervention due to lack of distress; these men agreed to complete follow-up questionnaires in the information-only arm. Randomization was therefore changed from 1 intervention:1 control to 3:1 to ensure sufficient participants completed the intervention.

Results

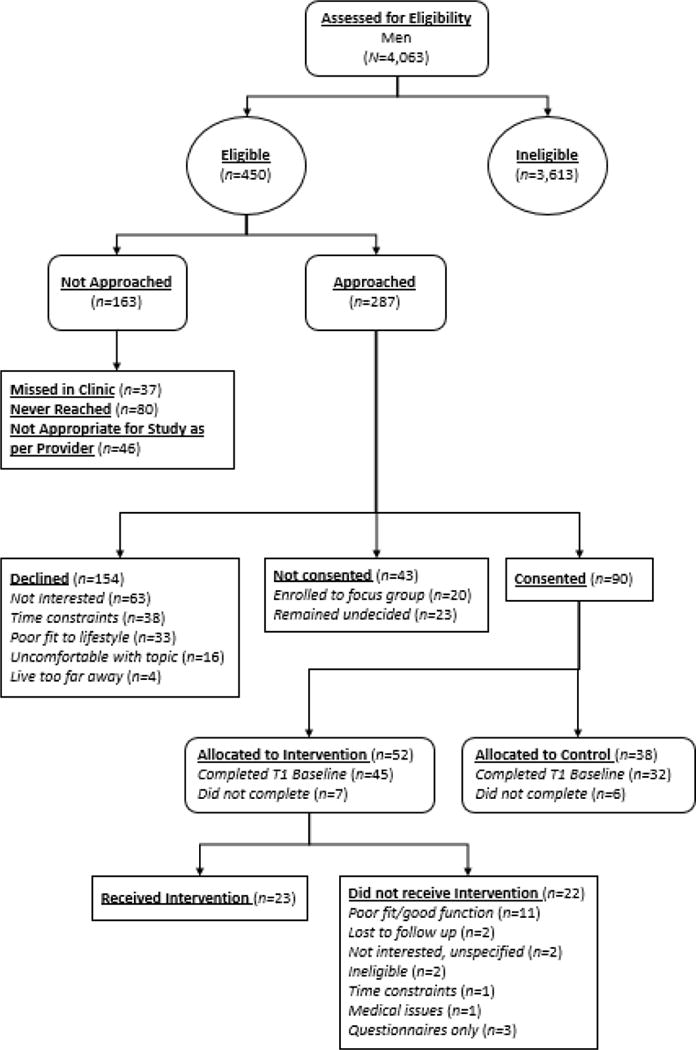

Four-hundred-fifty men were deemed eligible to be approached for additional screening based on their medical record (see Figure 1). Of these, 163 (36%) were not approached because they were missed at clinic (n=37), never reached (n=80), or their provider requested that they not be approached (n= 46). Of the 287 men approached, 43 were not consented to the intervention study (20 enrolled in study focus group, 23 remained undecided), and 154 declined participation (63% of eligible/decided). The primary reason cited was disinterest (n=63, 41%), followed by time constraints (n=38, 25%), poor fit to lifestyle (n=33, 21%), discomfort with the topic (n=16, 10%), and living too far away (n=4, 3%).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

As such, 90 men were randomized between the intervention (n=52) and control (n=38). Of the 45 (87%) men who were randomized to the intervention arm and completed baseline questionnaires, 22 (49%) declined to participate in the intervention. The primary reason given was lack of distress from their sexual function problems (n=11, 50%).

Discussion

The majority of men experiencing sexual side effects following treatment for rectal or anal cancer eligible for an intervention to improve their sexual functioning declined to participate. Barriers existed during eligibility screening, consenting, and adherence, although recruitment [8] and retention [6] rates were comparable to prior sexual health intervention studies among prostate cancer survivors. Of those men consented and randomized to the intervention, half did not participate. Given that there is a high risk for sexual dysfunction following treatment for rectal and anal cancer [3] and a strong interest among male survivors of cancer for sexual functioning education and interventions [5], addressing the unique barriers to accessing treatment for sexual side effects for this population is necessary to improve acceptability and feasibility of sexual health interventions.

Of eligible participants, almost two-thirds declined to participate. Prior qualitative research among male rectal and anal cancer survivors suggests men mentally triage sexual functioning side-effects behind survival during treatment. Many men did not attribute their sexual dysfunction to treatment, possibly due to limited information provided by physicians about sexual functioning side effects of treatment, and instead believed their dysfunction was normative [5]. Although time since treatment was not related to attrition in a sexual health intervention among prostate cancer survivors [6], recruiting for these interventions around treatment conclusion may better capture survivors’ interest when long-term treatment side-effects move into their attentional foreground.

This intervention was also delivered among female survivors [7,9], and recruitment challenges differed between genders. Providers were more likely to screen out men (28%) than women (5%) for participation in the study. Unfortunately, reasons for physician refusal for the study team to approach a patient were not collected.

Compared to eligible women (53%), a higher proportion of eligible men declined to participate (63%). Men and women equally declined due to poor perceived fit with their lifestyle (21% men vs. 20% women, respectively) and discomfort with the topic (10% vs. 10%), whereas women more often cited disinterest (41% vs. 49%). The misperception that sexual well-being is irrelevant for certain survivors (e.g., older, unpartnered) and the taboo nature of sexuality in many cultures are common barriers reported across sexual health observational and interventional psycho-oncology research [3]. The finding that men more often cited inability to make the time commitment (25% vs. 14%) fits with qualitative findings from the intervention development phase, in which men suggested the primary treatment barrier would be scheduling logistics [5]. Sexual health interventions designed to be brief, flexible, and telehealth-based may be particularly attractive for men, while culturally-sensitive sexual health education will likely be beneficial to meeting all survivors’ multifaceted wellness needs following cancer treatment.

Lastly, women who were randomized to the intervention were more likely to attend at least one or more treatment sessions (74%) relative to men (44%). Men who endorsed both difficulty with sexual functioning and distress from this difficulty were more likely to adhere to the intervention. Findings reinforce that physical sexual dysfunction symptoms do not automatically confer psychological distress, yet the overall discrepancy between survivors’ expressed interest in interventions addressing sexual dysfunction [5] and their enrollment in and adherence to such interventions is notable.

Clinical Implications

Applying clinical frameworks that specifically target ambivalence and avoidance to intervention recruitment may narrow this gap between enrollment and engagement. Motivational interviewing (MI) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) are two such patient-centered approaches that seek to overcome barriers to change (e.g., discomfort, avolition) by connecting behavior to patients’ values (e.g., physical intimacy) and long-term goals (e.g., satisfactory erectile functioning). Incorporating values assessment and motivational enhancement techniques into recruitment may increase interest in symptom management interventions by justifying the effort of engaging in the program with potential for personally-relevant gains.

Study Limitations

As aforementioned, the study did not collect reasons for physicians excluding participants from recruitment. This represents an important future area of research to better understand how physicians facilitate versus gate-keep to research studies. Moreover, examination of enrollment differences by demographic characteristics was impossible due to data being destroyed to protect privacy for all patients who were potentially eligible but not ultimately enrolled.

Despite prevalent symptoms of sexual dysfunction, few male survivors of rectal and anal cancer agreed and adhered to a sexual health intervention—a notable discrepancy between expressed interest and engagement in the intervention. There were recruitment and retention challenges both unique to men and comparable to those among women. Despite interest in, and demonstrated efficacy of, psychosocial interventions for managing sexual dysfunction among other distressing symptoms, significant barriers to implementation of psycho-oncology interventions exist. Better understanding barriers common across interventions and settings, as well as those unique to patient populations and intervention targets, is critical to improve the study design and dissemination of psycho-oncology interventions.

Male survivors of rectal and anal cancers frequently express interest in sexual health treatments, yet recruitment challenges to relevant intervention studies are significant.

Almost two-thirds of eligible male survivors declined participation for a sexual health intervention, primarily citing disinterest.

Of men randomized to the intervention, almost half declined to participate, primarily citing lack of distress from sexual dysfunction—a notable discrepancy between expressed interest and engagement in the intervention.

Tailoring men’s sexual health interventions to be low-burden may be particularly important for implementation and dissemination of such interventions.

Broader education about sexual health in cancer survivorship, as well as tailoring recruitment and intervention to survivors’ values and long-term goals, may increase engagement in sexual health interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Support was provided by NCI (R21CA129195-0:DuHamel; T32CA009461:Ostroff; P30CA008748:Thompson).

References

- 1.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrykowski MA, Manne SL. Are psychological interventions effective and accepted by cancer patients? I Standards and levels of evidence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;32:93–97. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3202_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: Challenges and intervention. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:3712–3719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendren SK, O’Connor BI, Liu M, Asano T, Cohen Z, Swallow CJ, MacRae HM, Gryfe R, McLeod RS. Prevalence of male and female sexual dysfunction is high following surgery for rectal cancer. Annals of Surgery. 2005;242:212–223. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171299.43954.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball M, Nelson CJ, Shuk E, Starr TD, Temple L, Jandorf L, Schover L, Mulhall JP, Woo H, Jennings S. Men’s experience with sexual dysfunction post-rectal cancer treatment: A qualitative study. Journal of Cancer Education. 2013;28:494–502. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0492-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2689–2700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings S, Philip EJ, Nelson C, Schuler T, Starr T, Jandorf L, Temple L, Garcia E, Carter J, DuHamel K. Barriers to recruitment in psycho-oncology: Unique challenges in conducting research focusing on sexual health in female survivorship. Psycho-oncology. 2014;23:1192. doi: 10.1002/pon.3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manne SL, Kissane DW, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Winkel G, Zaider T. Intimacy‐enhancing psychological intervention for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners: A pilot study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;8:1197–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuHamel K, Schuler T, Nelson C, Philip E, Temple L, Schover L, Baser RE, Starr TD, Cannon K, Jennings S. The sexual health of female rectal and anal cancer survivors: Results of a pilot randomized psycho-educational intervention trial. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2016;10:553–563. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, Sui D, Neese L, Jenkins R, Rhodes MM. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118:500–509. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]