Abstract

Background

After hepatectomy, over- and under-resuscitation induce cardiopulmonary complications and acute kidney injury, respectively, leading to significant perioperative morbidity and mortality. Unlike serum chemistries or urine output, serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels have been shown to accurately reflect current intravascular fluid balance without influence from alterations of hormonal axises. Based on these data, this study was designed to measure the impact of a serum BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol on the incidence of post hepatectomy cardiopulmonary/renal complications.

Methods

Hepatectomy patients registered in a single institution ACS-NSQIP database between 2011–2016 were examined in real-time for the development of cardiopulmonary/renal complications and divided into pre (2011–2013) and post (2014–2016) implementation of a BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol groups.

In the post-implementation group, maintenance fluids were tapered on a set protocol. Bolus fluids, diuresis, and micro-adjustments in fluid rate were guided by daily BNP values.

Results

Four hundred twenty-sixty patients underwent hepatectomy in the study period with 251 patients in the pre- and 209 patients in the post-protocol implementation groups. Cardiopulmonary/renal complication rates were 4.0% in the pre-protocol group and reduced to 0.9% after initiation of the BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol (p=0.04).

Conclusions

Despite low event rates, these data suggest that goal-directed postoperative fluid therapy with the combination of a hepatobiliary fluid protocol and serum BNP-guided volume management is superior to traditional chemistry and bedside volume assessment and can reduce post hepatectomy cardiopulmonary and renal complications.

Keywords: Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), hepatectomy, cardiopulmonary, renal, complications

Introduction

Maintenance of euvolemia after hepatectomy is essential to preserve effective circulatory blood volume and organ perfusion. Hypo- or hypervolemia resulting in fluid imbalance in the postoperative period can lead to prolonged hospital stay, increased morbidity, and development of cardiopulmonary and/or renal complications.1 Traditional noninvasive modalities of assessing volume status, such as urine output and serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (CRN) levels, can be inaccurate in the setting of baseline renal insufficiency, alterations of the hormonal axis, and fluid third-spacing.2 Change in body weight over time, which is one of the most accurate measures of volume status, is often inadequate because of lack of dependable measurements.3 Although invasive measures of cardiac output and intravascular fluid status can provide more precise data, a monitored intensive care unit is required and not practical for the routine awake floor patient. Therefore, a better measure is needed to help guide fluid therapy in the postoperative setting after liver resection.

Serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is a 32-amino-acid protein produced in the cardiac atria and ventricles in response to chamber dilation from volume expansion and pressure overload.4, 2 After release into the circulation, BNP promotes diuresis, natriuresis, reduction of preload, and afterload by binding to guanylate cyclase receptors on endothelial cells.4 When measured in surgical patients, BNP levels can provide prognostic and predictive value for development of postoperative complications.

The preoperative utilization of BNP for cardiac risk assessment in high-risk patients have been endorsed by The European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Anesthesiology.5, 6 Meta-analyses have demonstrated that an elevated preoperative BNP level is predictive of serious cardiovascular complications and when measured postoperatively provides additional risk stratification for mortality or nonfatal myocardial infarction after non-cardiac surgery.5, 7

BNP levels have also been shown to parallel changes in fluid balance and resuscitation. Friese et al. examined BNP levels in the trauma intensive care unit and found that serum levels increased with resuscitation.8 In the postoperative setting, Berri et al. demonstrated that serum BNP provided better intervascular volume assessment than did changes in the BUN/CRN ratio, particularly during the early phase of recovery from pancreatectomy.2 These data suggest that BNP levels can be used to guide fluid resuscitation and management in the postoperative period; however, no studies specific to liver surgery have validated these findings.

Of all the fields of surgery, liver surgery demands the most precision in intravascular volume management. Liver resections are associated with dramatic intravascular fluid shifts as patients are maintained in low central venous pressure states during parenchymal transection and aggressively resuscitated after completion. Subsequent liver function depends on maintaining a slight hypovolemic to euvolemic state, despite the confounders of fluid shifts and frequent use of epidural analgesia. These dynamic forces uniquely place the patient at risk for hypervolemic pulmonary, cardiac, and hepatic complications and hypovolemic renal complications. In order to address the need for more accurate volume assessment in liver surgery patients, this study was designed to measure the impact of a BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol on post-hepatectomy cardiopulmonary and renal complications.

Methods

Patients and Data Collection

Permission from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to data collection and analysis. Inclusion of institutional American College of Surgeons (ACS) National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) data was compliant with the NSQIP data use agreement. The institution subscribes to the “essentials model” in ACS-NSQIP with random collection of 14% of all surgical cases. Non-risk adjusted outcomes data were obtained from the institutional ACS-NSQIP database from January 2011 to December 2016 to identify all patients that underwent hepatectomy.

Pre-, intra-, and postoperative variables in the dataset were collected by Surgical Clinical Reviewers trained by NSQIP in medical record analysis. These variables included age, race, body mass index (BMI), presence of diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), myocardial infarction, intubation >48 hours, or acute kidney injury, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, operative procedure, operative time, type of perioperative analgesia, length of hospitalization, and pathology. A Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was calculated for each patient using the formula: 3.78×ln[serum bilirubin (mg/dL)] + 11.2×ln[INR] + 9.57×ln[serum CRN (mg/dL)] + 6.43. The most immediate preoperative levels of serum bilirubin, INR, and CRN were also recorded.

Overall and severe complication rates were recorded for the entire cohort. Severe complications were defined as development of the following NSQIP-specified occurrences: return to the operating room, organ space infection, dehiscence, ventilator dependence or failure to wean >48 hours, reintubation, acute renal insuf ciency or failure, cardiac arrest or myocardial infarction, stroke or coma, venous thromboembolism, sepsis or septic shock, or pneumonia.

Postoperative serum BNP, BUN, and CRN levels and fluid balance (intake and output) were collected by retrospective chart review by the author for postoperative days 0–5. BNP levels were measured using the Alere Triage® BNP test with the Beckman Coulter® Access Immunoassay System. This system employs a mouse monoclonal anti-human antibody, and testing was performed in our institutional central laboratory. Hospital cost, including overhead, for this test was $12.20.

Two groups outcomes were assessed and compared; pre (2011–2013) and post (2014–2016) implementation of the BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol.

To determine the ability of the protocol to prevent both hypovolemic and hypervolemic complications, the cardiopulmonary/renal (CP/R) complications were evaluated using data from the NSQIP dataset as a composite measure of myocardial infarction, intubation >48 hours, need for reintubation, or development of acute kidney injury (CRN > 2 mg/dl).

BNP-Guided Hepatobiliary Fluid Protocol

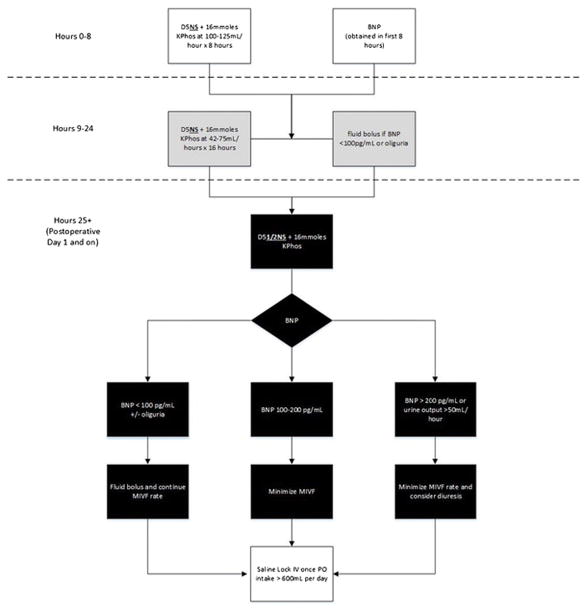

In the first 8 hours postoperatively, patients were resuscitated with D5NS+16mmoles potassium phosphate (KPhos) at 100–125mL/hour (16 mmol of KPhos contains 24 mEq of potassium). During the next 16 hours (hours 9–24), when the patient was experiencing peak third-spacing, the normotonic fluid rate was decreased to 42–75 mL/hour determined by early postoperative BNP level and urine output. On the afternoon of postoperative day 1, the fluid composition was changed to D5 1/2NS + 16mmoles KPhos at a rate of 42–75 mL/hour based on daily BNP level and urine output.

If BNP was <100 pg/mL or urine output decreased to < 50mL/2 hours, a 250–500 mL 5% albumin bolus was administered and the maintenance fluid rate was kept constant.

If BNP was 100–200pg/mL, no bolus was given and the maintenance intravenous (IV) fluid rate was minimized. If patients had an elevated BNP >200pg/mL, the maintenance IV fluid rate was minimized or stopped and diuresis considered. Patients with early, extreme or persistent BNP elevations were urgently evaluated for diastolic dysfunction or heart failure. Once a patient was able to tolerate >600mLs of oral intake per day, maintenance fluids were stopped according to enhanced recovery guidelines (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Evans, Pisters, and Lee, BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol algorithm. Oliguria is defined as urine output <50 mL/2 hours. KPhos: Potassium phosphate; BNP: Brain natriuretic peptide; MIVF: maintenance intravenous fluid

Statistical Analysis

Two groups’ outcomes were assessed and compared: pre- (2011–2013) and post- (2014–2016) implementation of the BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol. The pre-implementation and post-implementation groups were compared for the incidence of comorbidities and case types. Likewise, complication, readmission, and mortality rates were compared. In the 2014–2016 group, fluid balance (intake and output) and serum BNP, BUN, and CRN levels were examined for postoperative days 0 through 5. Fluid balance was calculated by the difference between intake and output for a given postoperative day. Serum BNP level was evaluated as an individual value. BUN and CRN were evaluated as a composite ratio expressed as BUN divided by CRN. Box plots were created to evaluate the distribution of fluid balance (Intake minus Output), serum BNP level, and BUN/CRN ratio for each postoperative day.

Data analysis was performed utilizing the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 22.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL). All tests were 2-sided, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Chi-square analyses were used to evaluate associations between categorical variables, and Student’s t-test used to evaluate differences in means between two groups of normally distributed continuous variables.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Four hundred sixty NSQIP-registered patients underwent hepatectomy during the study period: with 251 patients in the pre- and 209 patients in the post-BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol implementation groups.

Table 1 provides the descriptive characteristics of the patient population. Fifty-two percent of patients were male, the median age was 56 years, the median BMI was 27 g/m2, and 85% of patients were white. Diabetes (insulin or non-insulin dependent) was present in 11%, 8% were smokers, 0.4% had COPD, and 37% had hypertension. Ninety-one percent of patients had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of 3, and the median MELD score was 7. Open surgery was performed in 97% of cases; 61% underwent a partial hepatectomy, 17% a trisegmentectomy, 15% a right hepatectomy, and 4% a left hepatectomy. The median operative time was 250 minutes, and the median length of hospital stay was 6 days. Fifty-seven percent of patients had had a prior abdominal operation and 56% had received systemic chemotherapy < 90 days before the operation.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Total Patient Population and Groups Stratified by Pre- versus Post-Implementation of the BNP-Guided Hepatobiliary Fluid Protocol

| Variable | All Patients (n=460) | Pre-Protocol, 2011–2013 (n=251) | Post-Protocol, 2014–2016 (n=209) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Gender, no. (%) | ||||

| Female | 219 (48) | 118 (47) | 101 (48) | 0.79 |

| Male | 241 (52) | 133 (53) | 108 (52) | |

|

| ||||

| Age, median (range) or mean, years | Median 56 (range 19–89) | Mean 55 | Mean 57 | 0.68 |

|

| ||||

| Body mass index, median (range) or mean, g/m2 | Median 27 (range 16–52) | Mean 28 | Mean 27 | 0.28 |

|

| ||||

| Race, no. (%) | 0.46 | |||

| White | 392 (85) | 214 (85) | 178 (85) | |

| African American | 27 (6) | 17 (7) | 10 (5) | |

| Asian | 18 (4) | 10 (4) | 8 (4) | |

| Other | 23 (5) | 10 (4) | 13 (6) | |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 0.56 | |||

| No | 410 (89) | 227 (90) | 183 (88) | |

| Insulin dependent | 16 (4) | 17 (7) | 17 (8) | |

| Non-insulin dependent | 34 (7) | 7 (3) | 9 (4) | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking status, no. (%) | 0.33 | |||

| Current smoker within 1 year | 37 (8) | 23 (9)228 (91) | 14 (7)195 (93) | |

| Non-smoker | 423 (92) | |||

|

| ||||

| COPD, no. (%) | 0.23 | |||

| Yes | 2 (0.4) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| No | 458 (99.6) | 249 (99) | 209 (100) | |

|

| ||||

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 0.37 | |||

| Yes | 170 (37) | 95 (38) | 75 (36) | |

| No | 290 (63) | 156 (62) | 134 (64) | |

|

| ||||

| American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, no. (%) | 0.13 | |||

| 2 | 37 (8) | 25 (10) | 12 (6) | |

| 3 | 419 (91) | 224 (89) | 195 (93) | |

| 4 | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | |

|

| ||||

| Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score, median (range) or mean | Median 7 (range 6–16) | Mean 7 | Mean 7 | 0.53 |

|

| ||||

| Type of liver resection, no. (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Partial hepatectomy | 286 (62) | 133 (53) | 153 (74) | |

| Left hepatectomy | 19 (4) | 16 (6) | 3 (1) | |

| Right hepatectomy | 68 (15) | 45 (18) | 23 (11) | |

| Trisegmentectomy | 73 (16) | 48 (19) | 25 (12) | |

| Other | 14 (3) | 9 (4) | 5 (2) | |

|

| ||||

| Type of operation | 0.02 | |||

| Open | 446 (97) | 247 (98) | 199 (95) | |

| Laparoscopic | 14 (3) | 4 (2) | 10 (5) | |

|

| ||||

| Duration of procedure, median (range) or mean, minutes | Median 250 (range 40–963) | Mean 240 | Mean 299 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Length of hospital stay, median (range) or mean, days | Median 6 (range 1–47) | Mean 7 | Mean 6 | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Tumor pathology, no. (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Colorectal liver metastases | 300 (65) | 183 (73) | 117 (56) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 39 (8) | 8 (3) | 31 (15) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 29 (6) | 14 (6) | 15 (7) | |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 12 (3) | 7 (3) | 5 (2) | |

| Secondary liver metastases | 54 (12) | 27 (11) | 27 (13) | |

| Other | 26 (6) | 12 (5) | 14 (7) | |

The postoperative overall complication rate was 13%, and the severe complication rate was 10%. Transfusions were administered to 11% (n=49) of patients, with a median of 2 units of blood. No patients died within 90 days of surgery.

Between the pre- and post-intervention groups there were no differences in demographic or comorbidity distributions (Table 1). Regarding case magnitude, there was a trend toward parenchymal-sparing hepatectomy, but this also correlated with an increase in case length (Table 1).

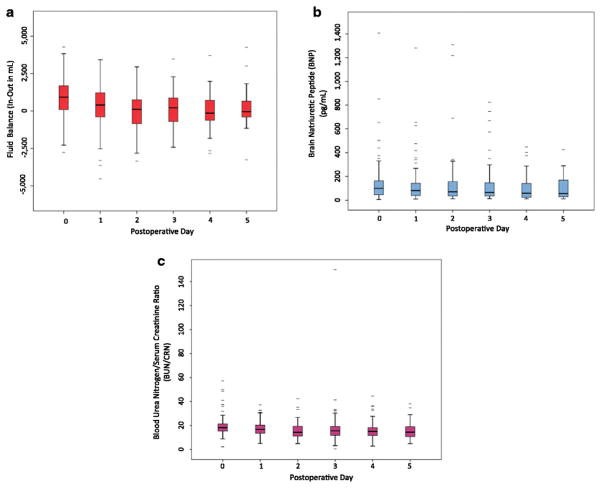

Within the post-intervention cohort, 75% of patients had BNP values either > 200 pg/ml or < 100 pg/ml. In these patients, BNP values were actively used to assist fluid management decision-making (Figure 2). The actionable range for volume adjustment is broader for BNP (25%–75%: 34 to 184 pg/mL) when compared to BUN (25%–75%: 9 to 17) or CRN (25%–75%: 0.6 to 1.0), where the ranges were narrower.

Figure 2.

Box plot for serum BNP levels of all 209 patients who underwent hepatectomy after implementation of the brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol (2014–2016). The y-axis scale is changed to highlight the therapeutic range in which changes to fluid balance can be made based on serum BNP levels. From postoperative day 0 to day 5, BNP was >200 pg/ml or < 100 pg/ml an average of 75% of the time.

Diuresis was administered to 12% of patients who were clinically asymptomatic with BNP values >200pg/mL. Fluid bolus was given to 5% of patients with a normal urine output and BNP value <100 pg/mL.

Cardiopulmonary/Renal Complications

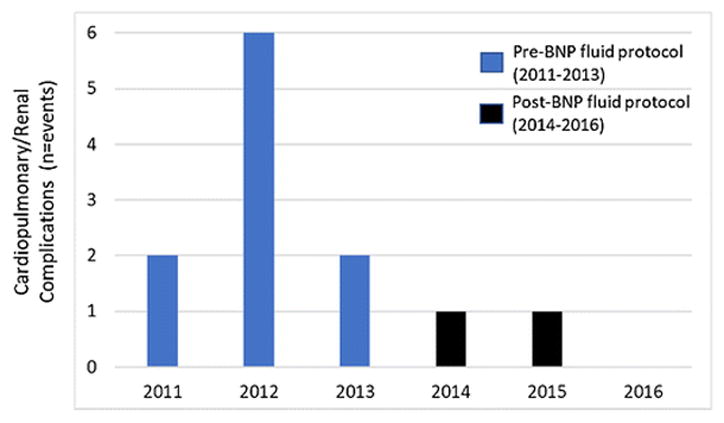

Overall, the CP/R complication rate was 3%. In the pre-implementation group, the CP/R complication rate was 4.0% (n=10), while only 0.9% (n=2) of post-protocol implementation patients experienced CP/R complications (P=0.04).

Within the composite complication metric consisting of myocardial infarction, need for intubation (either reintubation or prolonged postoperative intubation), and acute kidney injury, none of the patients developed a myocardial infarction; nine required intubation, which was secondary to volume overload; and three patients developed acute kidney injury. Figure 3 shows CP/R events over the study time period.

Figure 3.

Bar graph showing Cardiopulmonary/renal complications over the study period. Pre- and post-BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol are depicted in blue and black, respectively.

Table 2 provides descriptive characteristics of the patients who developed CP/R complications. Within this subgroup, 58% were male, and the median age was 58 years. All patients who developed CP/R complications were white. None of the patients were smokers or had COPD, but 8% had insulin-dependent diabetes, and half had hypertension. Ninety-two percent of patients with these complications had an ASA status of 3 with 50% undergoing a partial hepatectomy, 25% a right hepatectomy, 17% a trisegmentectomy, and 8% a left hepatectomy. All cases were open with a median operative time of only 188 minutes.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 12 Patients Who Developed Cardiopulmonary/Renal Complications

| Variable | All patients N (percentage) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Female | 5 (42) |

| Male | 7 (58) |

|

| |

| Age (median) | 58 Range (38–70) |

|

| |

| Body mass index (median) | 25 Range (17–31) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 12 (100) |

| African American | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

|

| |

| Diabetes | |

| No | 11 (92) |

| Insulin dependent | 1 (8) |

| Non-insulin dependent | 0 (0) |

|

| |

| Smoker | |

| Current smoker within 1 year | 0 (0) |

| Non-smoker | 12 (100) |

|

| |

| COPD | |

| Yes | 0 (0) |

| No | 12 (100) |

|

| |

| Hypertension | |

| Yes | 6 (50) |

| No | 6 (50) |

|

| |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status classification | |

| 2 | 1 (8) |

| 3 | 11 (92) |

| 4 | 0 (0) |

|

| |

| Model for End Stage Liver Disease (median) | 7 Range (6–16) |

|

| |

| Type of Operation | |

| Partial hepatectomy | 6 (50) |

| Left hepatectomy | 1 (8) |

| Right hepatectomy | 3 (25) |

| Trisegmentectomy | 2 (17) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

|

| |

| Open | 12 (100) |

| Laparoscopic | 0 (0) |

|

| |

| Duration of Procedure in minutes (median) | 188 Range (77–963) |

|

| |

| Length of Hospital Stay in days (median) | 12 Range (5–47) |

|

| |

| Tumor Pathology | |

| Colorectal liver metastases | 2 (17) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 0 (0) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 (8) |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 0 (0) |

| Secondary liver metastases | 7 (58) |

| Other | 2 (17) |

Patients who developed a CP/R complication had a lower median preoperative albumin level (3.9 versus 4.2, P=0.007) and a higher postoperative transfusion rate (50% versus 10%, P<0.001). The development of these complications was significant as these patients had a longer average length of hospital stay than did patients who did not have these complications (6 days versus 12 days, P<0.001).

Fluid Volume Assessments

Box plots were created to examine the relationships between fluid balance (intake-output), BNP level, and BUN/CRN ratio for postoperative days 0–5 in the 209 patients in the post-protocol intervention group (Figure 4). There were no significant differences between median BNP values over the postoperative period (P>0.05), indicating that the hepatobiliary fluid protocol compensated for physiologic volume shifts to maintain fairly consistent intravascular volume status.

Figure 4.

Box plots (representing the 25th and 75th percentiles) for all 209 patients in the later (2014–2016) group after implementation of the brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol. Variables examined were (A) fluid balance (Intake minus Output), (B) serum BNP level, and (C) blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio on postoperative days 0 through 5 Outliers are marked with bars

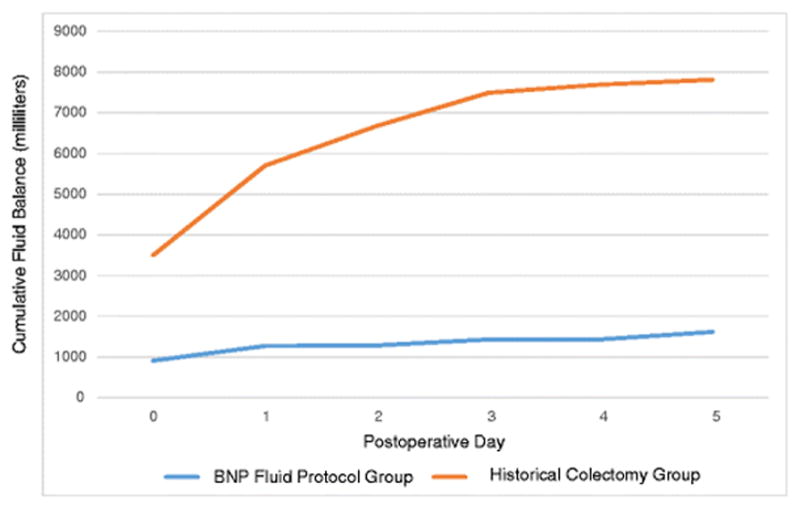

In Figure 5, cumulative fluid balance for the post-protocol implementation patients is shown in comparison to the standard fluid intake seen after colectomy, demonstrating that a low overall cumulative fluid balance was achieved using the BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol.

Figure 5.

Cumulative fluid balance of the 209 patients in the post-fluid protocol implementation group over postoperative days 0–5. A historical fluid balance plot after colectomy is shown for comparison.

Discussion

Balanced fluid resuscitation to achieve euvolemia is of paramount importance in patients undergoing liver surgery. The development of either volume overload of the intravascular and interstitial fluid compartment or hypovolemic under-resuscitation can result in increased morbidity, prolonged hospital stay, and even mortality. To date, highly accurate postoperative measures of volume status that account for physiologic and iatrogenic fluid shifts are lacking. In an effort to enhance “Precision Liver Surgery”, this study proposed the combination of a regimented hepatobiliary fluid protocol with BNP-based modifications to improve patient outcomes.9

Analysis of the outcomes data in this study demonstrates that utilization of a BNP-guided hepatobiliary fluid protocol can help the clinical team to maintain patient euvolemia. By simultaneously limiting unnecessary fluid administration and guiding appropriate fluid supplementation the protocol reduced both cardiopulmonary and renal complications.

There are several additional positive attributes of the protocol. First, the protocol is non-invasive. Invasive methods of measuring volume status are not practical in the routine, awake, hepatectomy patient. BNP level can provide a noninvasive means of determining intravascular volume status that is more immediate, accurate, and actionable than BUN and CRN levels or ratio. Second, BNP testing is inexpensive. At our institution, the test has a cost of only $12.20 per sample. This cost is easily justified against a return on investment of 3 out of every 100 patients avoiding cardiopulmonary and/or renal complications, which in our study resulted in a doubling of length of stay. In addition, cost savings are further accentuated by the protocol’s ability to refine and limit the indications for relatively expensive albumin fluid boluses. Third, BNP is constitutively produced, not stored, and has a short half-life of 21 minutes, thereby allowing for real-time and repeated assessments of serum levels. Fourth, BNP is degraded by natriuretic peptide C receptors and neutral endopeptidases, maintaining its reliability as a marker of intravascular volume status even in situations of decreased glomerular filtration rates.10 Fifth, early, extreme, and/or persistent elevations of BNP can signal the potential of underlying cardiac dysfunction that may have catastrophic consequences if left untreated.

Previous studies, performed in postoperative oncologic but not hepatectomy patients, have demonstrated that variations in BNP levels parallel intravascular fluid shifts.2, 11 To our knowledge, this is the first study to corroborate these findings in the hepatectomy patient population, where intravascular fluid shifts can be particularly prevalent and impactful on outcomes. Likewise, this is the first study to report the utilization of BNP levels to make specific decisions on fluid adjustments using a regimented protocol.

The maintenance hepatobiliary fluid choice used in this protocol deserves additional discussion. The maintenance fluid portion of this regimen, including the composition of the fluids and the strategy for tapering sodium concentration and rate, has been used in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery at our institution for over 15 years. The “invention” of the regimen is attributed to Douglas Evans, MD, Peter Pisters, MD, and Jeffrey E. Lee, MD. The rationale for the protocol is that the patient is maintained on an initially high rate of normotonic saline during the first 24 postoperative hours, competing against cortisol-induced third-spacing when its effect is at its maximum. Giving 1/2 normal saline during this critical phase, a common practice throughout most of gastrointestinal surgery, results in donation of at least half the delivered volume to the interstitial tissues, with multiple adverse sequelae, including poor renal perfusion, almost universally resulting in early oliguria and the need for fluid boluses. Matching the rate and tonicity of fluid to the patient’s most intravascularly dry period, the hepatobiliary fluid protocol reduces bolus demand to less than one per patient on average. Although it is generally felt that excessive saline can be harmful to postoperative liver function, we find that this is not seen in our liver patients when the isotonic saline is limited to the first 24 hours, including in patients with cirrhosis.12–14 The benefits of this practice are considerable, and the hepatic-specific risk is negligible to non-existent.

After this acute 24-hour period the maintenance fluids are transitioned to a D51/2NS solution, limiting the sodium load and avoiding hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and its associated coagulopathy. The addition of 16mmoles KPhos was chosen as it provides 24mEquivalents potassium and a continuous supplementation of phosphate. In hepatectomy patients, the phosphate infusion is critical to provide substrate for ATP production in the rapidly regenerating liver, avoiding potentially morbid depletion of phosphate stores and muscular failure. We find that the more robust continuous supplementation of both potassium and phosphorus is valuable for non-liver patients, as well, as it significantly reduces ileus and clinician and nursing staff workload with significantly lower requirements for electrolyte boluses to maintain normal laboratory levels. In the absence of preexisting renal insufficiency or acute kidney injury, early mild elevations in serum potassium and/or phosphorus that occur on the regimen are harmless and rapidly return to normal without intervention as the IVF rate is tapered on the protocol. In this study cohort, transient mild hyperphosphatemia and/or hyperkalemia did develop in 15% of patients. All cases of hyperkalemia resolved without additional intervention and were tolerated without any adverse cardiac events or arrhythmias.

During the two time periods, 2011–2013 and 2014–2016, there were no major changes in the operative techniques utilized at this institution. The two-surgeon technique with saline-linked cautery and ultrasonic dissection has been the standard strategy for parenchymal transection and routine intraoperative air leak test was utilized for major hepatectomies to reduce the rate of postoperative biliary fistula. 15,16 Despite a heavily pretreated population with frequent preexisting anemia, red blood cell transfusion rates were low, and no other blood product types were given.17 There was a trend toward more parenchymal-sparing hepatectomy, which could be interpreted as a covariate for reduced complications. However, while these procedures reduced the risk of postoperative hepatic insufficiency by preserving remnant liver volume, they paradoxically require more frequent and prolonged inflow occlusion and may not necessarily be less risky in the early postoperative period. To reinforce this point, patients in the post-implementation cohort had significantly longer operative times, which likely put them at increased risk for cardiopulmonary and/or renal complications. Our enhanced recovery protocol was initiated January of 2011.

Although euvolemia was achieved postoperatively using the postoperative fluid protocol, it is important to note that this program was coupled with intraoperative goal-directed therapy. Throughout the study period, previously reported uniform intraoperative goal-directed fluid and blood product replacement protocols were utilized.17 For over a decade, we have not used central venous catheters; instead optimal intraoperative resuscitation was accomplished by effective cross-table communication with anesthesia during the entire case, judicious use of fluids and vasopressors, and non-invasive stroke volume variation monitoring using an arterial line.

There are several limitations of this study. Because institutional NSQIP data were used, there are more granular cardiopulmonary outcomes that were not captured by the database, such as arrhythmias, pulmonary effusions, and pulmonary edema. However, had these issues arisen and progressed, their more serious associated events, including reintubation, would have been captured. Another potential critique is that we did not routinely obtain preoperative BNP levels. Although these would have provided a baseline, and they may have some prognostic value, in the absence of a history of congestive heart failure or new cardiac signs and symptoms preoperative BNP has not been shown to aid in management of non-cardiac surgery patients.5, 1 It could also be argued that our findings can be attributed to general increased vigilance. Although it is difficult to refute this possibility, during these time periods the level of the trainee (complex general surgical oncology fellow and hepatopancreatobiliary fellow) and advanced practice provider caring for these patients did not change, and all other order sets remained the same. Finally, because of the low event rate, only a limited number of prognostic and predictive risk factors for the development of CP/R complications were identified.

Conclusions

Our data and analysis indicate that intraoperative goal-directed therapy coupled with our programmatic hepatobiliary fluid protocol with serum BNP-guided modifications is a simple, ubiquitously available, evidence-based, and cost-saving practice that facilitates increased precision in the care of liver surgery patients, reduces resources needed for IV boluses, and leads to better outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grants T32 CA009599.

Supported by the NIH/NCI under award number P30CA016672, T32 CA009599, and used the Clinical Trials Support Resource.

Footnotes

The NIH had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication

Presentation: This work was presented as an oral presentation at the 2017 Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association (AHPBA) Annual Meeting.

Author Contributions:

Patel: design of the work, data acquisition/analysis, drafting and critical revisions of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript

Kim: design of the work, data acquisition/analysis, drafting and critical revisions of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript

Tzeng: conceptualization, data analysis, critical revisions of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript

Chun: conceptualization, data analysis, critical revisions of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript

Conrad: conceptualization, data analysis, critical revisions of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript

Vauthey: conceptualization, data analysis, critical revisions of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript

Aloia: design of the work, data analysis, drafting and critical revisions of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript

References

- 1.Varadhan KK, Lobo DN. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of intravenous fluid therapy in major elective open abdominal surgery: getting the balance right. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2010;69(4):488–98. doi: 10.1017/s0029665110001734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berri RN, Sahai SK, Durand JB, Lin HY, Folloder J, Rozner MA, et al. Serum brain naturietic peptide measurements reflect fluid balance after pancreatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(5):778–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lodeserto JA, Chohan H, Payne RB. Accuracy of daily weights and fluid balance in medical intensive care unit patients with the intervention of electronic medical records and electronic bedside weight measurements. Chest. 2009;136(15S) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonow RO. New insights into the cardiac natriuretic peptides. Circulation. 1996;93(11):1946–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.11.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodseth RN, Biccard BM, Le Manach Y, Sessler DI, Lurati Buse GA, Thabane L, et al. The prognostic value of pre-operative and post-operative B-type natriuretic peptides in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: B-type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal fragment of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63(2):170–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Boersma E, De Hert S, Eeckhout E, Fowkes G, et al. Guidelines for pre-operative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative cardiac management in non-cardiac surgery. European heart journal. 2009;30(22):2769–812. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodseth RN, Lurati Buse GA, Bolliger D, Burkhart CS, Cuthbertson BH, Gibson SC, et al. The predictive ability of pre-operative B-type natriuretic peptide in vascular patients for major adverse cardiac events: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58(5):522–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friese RS, Dineen S, Jennings A, Pruitt J, McBride D, Shafi S, et al. Serum B-type natriuretic peptide: a marker of fluid resuscitation after injury? The Journal of trauma. 2007;62(6):1346–50. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31804798c3. discussion 50–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong J, Yang S, Zeng J, Cai S, Ji W, Duan W, et al. Precision in liver surgery. Seminars in liver disease. 2013;33(3):189–203. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Troughton RW, Richards AM. B-type natriuretic peptides and echocardiographic measures of cardiac structure and function. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2009;2(2):216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher SBRS, Hess K, Grotz TE, Mansfield PF, Royal R, Badgwell B, Fleming J, Fournier KF, Mann GN. Elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is an early marker for patients at risk for complications after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS + HIPEC). Abstract Society of Surgical Oncology Meeting; March 2017; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melloul E, Hubner M, Scott M, Snowden C, Prentis J, Dejong CH, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Liver Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations. World journal of surgery. 2016;40(10):2425–40. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3700-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCluskey SA, Karkouti K, Wijeysundera D, Minkovich L, Tait G, Beattie WS. Hyperchloremia after noncardiac surgery is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality: a propensity-matched cohort study. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2013;117(2):412–21. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318293d81e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw AD, Bagshaw SM, Goldstein SL, Scherer LA, Duan M, Schermer CR, et al. Major complications, mortality, and resource utilization after open abdominal surgery: 0.9% saline compared to Plasma-Lyte. Annals of surgery. 2012;255(5):821–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825074f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aloia TA, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN. Two-surgeon technique for hepatic parenchymal transection of the noncirrhotic liver using saline-linked cautery and ultrasonic dissection. Annals of surgery. 2005;242(2):172–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171300.62318.f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmitti G, Vauthey JN, Shindoh J, Tzeng CW, Roses RE, Ribero D, et al. Systematic use of an intraoperative air leak test at the time of major liver resection reduces the rate of postoperative biliary complications. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(6):1028–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.07.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day RW, Brudvik KW, Vauthey JN, Conrad C, Gottumukkala V, Chun YS, et al. Advances in hepatectomy technique: Toward zero transfusions in the modern era of liver surgery. Surgery. 2016;159(3):793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]