Abstract

Background

Obesity has been linked to increased mortality in several cancer types; however, the relationship between obesity and survival in metastatic melanoma is unknown. The aim of this study was to examine the association between BMI, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) in metastatic melanoma.

Methods

This study included 6 independent cohorts for a total of 1918 metastatic melanoma patients. These included two targeted therapy cohorts [randomized control trials (RCTs) of dabrafenib and trametinib (n=599) and vemurafenib and cobimetinib (n=240)], two immunotherapy cohorts [RCT of ipilimumab + dacarbazine (DTIC) (n=207) and a retrospective cohort treated with anti-PD-1/PDL-1 (n=331)], and two chemotherapy cohorts [RCT DTIC cohorts (n=320 and n=221)]. BMI was classified as normal (BMI 18 to <25; n=694 of 1918, 36.1%) overweight (BMI 25-29.9; n=711, 37.1%) or obese (BMI≥30; n=513, 26.7%). The primary outcomes were the association between BMI, PFS, and OS, stratified by treatment type and sex. These exploratory analyses were based on previously reported intention-to-treat data from the RCTs. The effect of BMI on PFS and OS was assessed by multivariable-adjusted Cox models in independent cohorts. In order to provide a more precise estimate of the association between BMI and outcomes, as well as the interaction between BMI, sex, and therapy type, adjusted hazard ratios were combined in mixed-effects meta-analyses and heterogeneity was explored with meta-regression analyses.

Findings

In the pooled analysis, obesity, as compared to normal BMI, was associated with improved survival in patients with metastatic melanoma [average adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI: 0.77 (0.66-0.90) and 0.74 (0.58-0.95) for PFS and OS, respectively]. The survival benefit associated with obesity was restricted to patients treated with targeted therapy [0.72 (0.57-0.91) and 0.60 (0.45-0.79) for PFS and OS, respectively] and immunotherapy [0.75 (0.56-1.00) and 0.64 (0.47-0.86)]. No associations were observed with chemotherapy [0.87 (0.65-1.17) and 1.03 (0.80-1.34); treatment p for interaction = 0.61 and 0.01, for PFS and OS, respectively]. The prognostic effect of BMI with targeted and immune therapies differed by sex with pronounced inverse associations in males [PFS 0.67 (0.53-0.84) and OS 0.53 (0.40-0.70)], but not females [PFS 0.92 (0.70-1.23) and OS 0.85 (0.61-1.18), sex p for interaction= 0.08 and 0.03, for PFS and OS, respectively]

Interpretation

Obesity is associated with improved PFS and OS in metastatic melanoma, driven by strong associations observed in males treated with targeted or immune therapy. The magnitude of the benefit detected supports the need for investigation into the underlying mechanism of these unexpected observations

Funding

ASCO/CCF Young Investigator Award and ASCO/CCF Career Development Award to JLM

Introduction

Metastatic melanoma is an aggressive disease with poor outcomes historically. However, the outcomes of patients with metastatic melanoma have improved dramatically with the FDA approval of MAPK pathway-directed targeted therapies and checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapies.1–4 Despite these many new options, metastatic melanoma patient outcomes remain heterogeneous and many patients still succumb to this disease. An improved understanding of factors associated with clinical benefit from these treatments may improve their personalized use and provide new insights into resistance.

Obesity is an established risk factor for many malignancies, and is associated with worse outcomes in several cancers.5,6 However, higher BMI has also been associated with improved outcomes in some cancers,7–9 a phenomenon dubbed the “obesity paradox.”10 The role of obesity in melanoma has not been well-studied to date.5 Existing data suggests that obesity is associated with an increased risk of melanoma in men11 and increased primary tumor Breslow thickness.12 We recently demonstrated that obesity is associated with worse outcomes in a large cohort of patients with surgically resected melanoma.13 However, the association of BMI with outcomes in metastatic melanoma patients, particularly among those treated with contemporary targeted and immune therapies, is unknown. Notably, several known associations exist that could link obesity with worsened melanoma outcomes, including germline genetic variants in obesity-related genes associated with melanoma risk,14 inflammation,14 obesity-related cytokines,15 and adipocyte cross-talk.16 Of particular interest, the IGF-1/PI3K/AKT pathway has been shown to play a key role in the pathogenesis of obesity in cancer,17 and has also been implicated in resistance to both targeted and immune therapies in melanoma.18,19

Based on these data, we hypothesized that obesity would be associated with worse outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the association of BMI with progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in independent cohorts of metastatic melanoma patients treated with targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or chemotherapy. Given the well-documented sex disparity in melanoma outcomes,20 as well as sex differences in body composition, we also separately examined associations in male and female patients. Our analyses unexpectedly show that obesity is associated with significantly improved outcomes in metastatic melanoma patients. Moreover, our data suggests these effects are driven by a strong survival advantage associated with obesity in males treated with targeted therapy and with immune therapy.

Methods

Study design and cohort populations

We collated data from six clinical cohorts of metastatic melanoma patients treated with the three categories of FDA-approved therapies in this disease [targeted therapy (2 cohorts), immunotherapy (2 cohorts) or chemotherapy (2 cohorts)] All cohorts were comprised of patients treated on randomized controlled trials (RCTs), except a retrospective cohort of anti-PD1/PDL1.

Targeted therapy cohorts included a cohort of treatment-naive patients with BRAFV600–mutant metastatic melanoma treated with the BRAF inhibitor (BRAFi) + MEK inhibitor (MEKi) combination dabrafenib and trametinib (D+T; FDA approval, 2014) in the randomized clinical trials (RCTs) BRF113220 (part C), COMBI-d, and COMBI-v (n=617).4 A second cohort of patients treated with the only other FDA-approved BRAFi + MEKi combination for BRAFV600-mutant metastatic melanoma, vemurafenib and cobimetinib (V+C; FDA approval, 2016), in the phase III coBRIM RCT (n=247) served as a validation cohort (eligibility criteria appendix page 1).1 Immunotherapy cohorts included metastatic melanoma patients treated on the Phase III RCT CA 184-024 of ipilimumab (IPI, anti-CTLA-4, FDA approval 2011) + dacarbazine (DTIC) (n=250)2 and 342 metastatic melanoma patients treated with anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab, FDA approval 2014, n=261; nivolumab, FDA approval 2014, n=73) or anti-PDL-1 (atezolizumab, n=8) antibodies at 4 centers in the USA and Australia with clinical response assessment and survival data available. (eligibility criteria appendix page 1). Chemotherapy cohorts included metastatic melanoma patients treated with dacarbazine (DTIC) in the control arms of CA 184-0242 (n=252) and the Phase III BRIM3 RCT21 (n=338) (eligibility criteria appendix page 1).

Procedures

Patients without height or weight available for BMI calculation were excluded. BMI at treatment initiation was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of height (in meters) and categorized according to standard World Health Organization definitions of underweight (BMI<18.5), normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25-29.9), and obese (≥30). Underweight patients were excluded from analyses due to low prevalence (<2%) across the cohorts.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were the association of BMI category with progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) stratified by treatment group and sex. Secondary outcomes included the association of BMI with overall response rate (ORR), adverse events (AEs), and pharmacokinetics. Patients were followed from the date of treatment initiation or baseline randomization until disease progression [progression-free survival (PFS)] or death (OS). Disease progression and response rate were defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria. Outcomes data was provided by the sponsors of each of the trials and based on intention-to-treat analyses, other than the retrospective PD-1/PD-L1 cohort for whom outcomes were provided by medical oncologists of the collaborating institutions.

Statistical Analysis

For each clinical cohort, we evaluated the association of baseline BMI category with PFS and OS outcomes. Survival curves for PFS and OS across BMI category and by sex were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. We evaluated the association of BMI with prospective survival outcomes in Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for prognostic factors (defined in Table 2) in all patients, and in sex-stratified analyses. Logistic regression was used to assess associations of BMI with treatment response and pharmacokinetics. In all analyses, normal BMI was used as the reference category. Missing data was left out and not imputed.

Table 2.

Associations between BMI and PFS and OS

| Population | BMI | Patient No. (%) | PFS | OS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | Multivariable Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Univariate HR (95% CI) | Multivariable Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||

| Dabrafenib + Trametiniba | ||||||

| All patients (n=599) | 18.5–24.9 | 222 (37) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 231 (39) | 0.9 (0.76–1.19) | 0.95 (0.75–1.21) | 0.84 (0.65–1.10) | 0.78 (0.59–1.02) | |

| ≥30 | 146 (24) | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) | 0.75 (0.57–0.99) | 0.63 (0.46–0.86) | 0.59 (0.43–0.83) | |

| Male (n=347) | 18.5–24.9 | 109 (31) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 156 (45) | 0.85 (0.63–1.13) | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) | 0.73 (0.53–1.00) | 0.80 (0.57–1.11) | |

| ≥30 | 82 (24) | 0.69 (0.49–0.99) | 0.75 (0.52–1.08) | 0.46 (0.30–0.70) | 0.44 (0.29–0.69) | |

| Female (n=252) | 18.5–24.9 | 113 (45) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 75 (30) | 0.95 (0.65–1.39) | 1.05 (0.69–1.59 | 0.84 (0.52–1.35) | 0.65 (0.37–1.13) | |

| ≥30 | 64 (25) | 0.74 (0.48–1.12) | 0.83 (0.54–1.29) | 0.89 (0.55–1.45) | 0.93 (0.56–1.55) | |

| P–value for interactionb | 0.56 | 0.02 | ||||

| Vemurafenib + Cobimetinibc | ||||||

| All patients (n=240) | 18.5–24.9 | 85 (35) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 88 (37) | 0.73 (0.51–1.04) | 0.65 (0.43–1.00) | 0.86 (0.58–1.28) | 0.67 (0.43-1.06) | |

| ≥30 | 67 (28) | 0.62 (0.42–0.91) | 0.66 (0.42–1.02) | 0.64 (0.41–0.98) | 0.62 (0.37–1.02) | |

| Male (n=142) | 18.5–24.9 | 40 (28) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 58 (41) | 0.69 (0.44–1.07) | 0.62 (0.38–1.03) | 0.82 (0.51–1.35) | 0.67 (0.39–1.15) | |

| ≥30 | 44 (31) | 0.44 (0.26–0.73) | 0.59 (0.31–1.08) | 0.53 (0.29–0.93) | 0.68 (0.35-1.29) | |

| Female (n=98) | 18.5–24.9 | 45 (46) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 30 (31) | 0.64 (0.35–1.16) | 0.66 (0.27–1.58) | 0.71 (0.34–1.39) | 0.72 (0.27–1.83) | |

| ≥30 | 23 (23) | 0.92 (0.50–1.64) | 0.75 (0.37–1.51) | 0.75 (0.35–1.50) | 0.59 (0.25–1.29) | |

| P-value for interaction | 0.06 | 0.44 | ||||

| Ipilimumab + DTICd | ||||||

| All patients (n=207) | 18.5–24.9 | 68 (28) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 88 (37) | 0.87 (0.62–1.22) | 0.88 (0.61–1.26) | 0.76 (0.53–1.08) | 0.70 (0.48–1.03) | |

| ≥30 | 51 (21) | 0.67 (0.45–0.99) | 0.63 (0.41–0.95) | 0.64 (0.42–0.97) | 0.54 (0.34–0.86) | |

| Male (n=138) | 18.5–24.9 | 41 (29) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 64 (45) | 0.76 (0.50–1.16) | 0.77 (0.49–1.22) | 0.69 (0.45–1.07) | 0.63 (0.39–1.01) | |

| ≥30 | 33 (23) | 0.53 (0.32–0.88) | 0.55 (0.32–0.93) | 0.46 (0.27–0.80) | 0.40 (0.22–0.72) | |

| Female (n=69) | 18.5–24.9 | 27 (28) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 24 (24) | 1.02 (0.56–1.88) | 1.29 (0.66–2.51) | 0.79 (0.42–1.50) | 0.84 (0.43–1.64) | |

| ≥30 | 18 (18) | 1.02 (0.55–1.92) | 0.92 (0.45–1.86) | 1.13 (0.58–2.18) | 1.16 (0.55–2.46) | |

| P-value for interaction | 0.28 | 0.15 | ||||

| Anti-PD-1/PD-L1d | ||||||

| All patients (n=331) | 18.5–24.9 | 102 (31) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 109 (33) | 0.78 (0.56–1.07) | 0.82 (0.58–1.16) | 0.75 (0.52–1.10) | 0.78 (0.52–1.17 | |

| ≥30 | 120 (36) | 0.80 (0.58–1.10) | 0.85 (0.61–1.19) | 0.70 (0.48–1.01) | 0.72 (0.48–1.06) | |

| Male (n=214) | 18.5–24.9 | 57 (27) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 78 (36) | 0.62 (0.42–0.93) | 0.69 (0.45–1.07) | 0.59 (0.37–0.93) | 0.71 (0.44–1.17) | |

| ≥30 | 79 (37) | 0.62 (0.41–0.92) | 0.69 (0.45–1.06) | 0.62 (0.39–0.98) | 0.69 (0.42–1.12) | |

| Female (n=117) | 18.5–24.9 | 45 (38) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 31 (26) | 1.08 (0.62–1.88) | 1.10 (0.60–2.03) | 1.08 (0.56–2.08) | 1.00 (0.47–2.10) | |

| ≥30 | 41 (35) | 1.18 (0.70–1.96) | 1.25 (0.72–2.16) | 0.77 (0.40–1.49) | 0.72 (0.36–1.45) | |

| P-value for interaction | 0.07 | 0.84 | ||||

| DTIC (BRIM3)c | ||||||

| All patients (n=320) | 18.5–24.9 | 143 (45) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 107 (33) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 0.94 (0.70–1.25) | 1.05 (0.79–1.39) | 0.98 (0.73–1.31) | |

| ≥30 | 70 (22) | 0.86 (0.62–1.25) | 0.91 (0.64–1.26) | 0.92 (0.66–1.28) | 0.94 (0.66–1.32) | |

| Male (n=174) | 18.5–24.9 | 70 (40) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 73 (42) | 0.87 (0.61–1.25) | 0.91 (0.63–1.32) | 1.09 (0.76–1.57) | 0.97 (0.66–1.41) | |

| ≥30 | 31 (18) | 0.75 (0.46–1.20) | 0.73 (0.43–1.17) | 1.05 (0.64–1.68) | 0.92 (0.56–1.51) | |

| Female (n=146) | 18.5–24.9 | 73 (29) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 34 (23) | 0.97 (0.60–1.53) | 0.84 (0.49–1.40) | 1.00 (0.61–1.60) | 0.85 (0.50–1.40) | |

| ≥30 | 39 (27) | 0.97 (0.60–1.53) | 1.02 (0.63–1.65) | 0.82 (0.51–1.29) | 0.94 (0.57–1.52) | |

| P-value for interaction | 0.51 | 0.49 | ||||

| DTIC (CA 184-024)d | ||||||

| All patients (n=221) | 18.5–24.9 | 74 (33) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 88 (40) | 0.73 (0.52–1.01) | 0.81 (0.58–1.14) | 0.85 (0.61–1.19) | 0.91 (0.64–1.28) | |

| ≥30 | 59 (27) | 0.83 (0.59–1.18) | 0.96 (0.67–1.39) | 0.95 (0.66–1.37) | 1.16 (0.79–1.70) | |

| Male (n=140) | 18.5–24.9 | 38 (27) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 66 (47) | 0.62 (0.41–0.94) | 0.77 (0.50–1.18) | 0.72 (0.48–1.10) | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | |

| ≥30 | 36 (26) | 0.70 (0.44–1.12) | 1.06 (0.63–1.78) | 0.97 (0.60–1.56) | 1.55 (0.91–2.66) | |

| Female (n=81) | 18.5–24.9 | 36 (44) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–29.9 | 22 (27) | 1.08 (0.62–1.90) | 1.13 (0.63–2.01) | 1.06 (0.60–1.88) | 1.29 (0.70–2.36) | |

| ≥30 | 23 (28) | 1.04 (0.61–1.77) | 1.02 (0.58–1.77) | 0.88 (0.50–1.55) | 0.91 (0.51–1.64) | |

| P-value for interaction | 0.79 | 0.39 | ||||

CI= Confidence Interval. DTIC=dacarbazine. HR=hazard ratio. OS= overall survival. PFS= progression-free survival. PD-1/PD-L1= anti-PD-1 and anti-PDL1 antibody cohort.

Adjusted for age, stage, LDH, BRAF mutation, ECOG performance status, sum of target lesion diameters, number of disease sites, and prior adjuvant therapies as well as sex in overall cohort.

Interaction for sex × BMI was tested using BMI as a categorical variable (obese vs. normal) on multivariable hazard ratios

Adjusted for age, stage, LDH, mutation, and ECOG performance status as well as sex in overall cohort.

Adjusted for age, stage, LDH, and ECOG performance status as well as sex in overall cohort.

In addition to the analysis of each individual cohort, we combined adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) using the methods of mixed-effects meta-analysis to assess the prognostic effect of BMI on metastatic melanoma patient survival overall, by treatment type, and by sex. We explored possible sources of heterogeneity by using meta-regression analyses. We calculated separate average HRs for each treatment class, for each sex, and for each treatment class within each sex. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the Q and I2 statistic: I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% correspond to low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity. Statistical tests for interaction evaluated the significance of categorical cross-product terms in multivariable-adjusted models. Statistical analyses were performed utilizing SAS 9.4, JMP (SAS) 12, R 3.1.1, and S+ 8.0. All statistical tests were 2-sided and considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Role of the funding source

The funding source had no role study in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or writing of the manuscript. The corresponding authors had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Results

There were a total of 2046 patients in the 6 cohorts. 101 (4.9%) of the 2046 patients were excluded for lacking height and/or weight to calculate BMI. Of the 1945 patients with available BMI, 27 (1.4%) were underweight and were excluded due to low prevalence, leaving a total of 1918 patients in this analysis. Of these, 694 (36.1%) were normal weight, 711 (37.1%) were overweight, and 513 (26.7%) were obese. More than half of the patients (1155; 60.2%) were male.

Targeted therapy cohorts

BMI distribution for the D+T cohort reflected that of the overall cohort (appendix p 2). Clinical characteristics, including tumor burden, LDH, and ECOG PS were similar across normal, overweight, and obese BMI groups (Table 1 and appendix p 2). However, patients with higher BMI tended to be older, male, and less likely to have Stage M1C disease. As expected, obese patients had higher use of metabolic syndrome-associated medications (metformin, statins, beta blockers, and aspirin) (appendix p 2).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | D+T (n=599) | V+C (n=240) | IPI + DTIC (n=207) | PD-1/PD-L1 (n=331) | DTIC (BRIM3 (n=320) | DTIC (CA 184-024) (n=221) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI 18.5– 24.9 No. (%) |

BMI 25– 29.9 No. (%) |

BMI ≥30 No. (%) |

BMI 18.5– 24.9 No. (%) |

BMI 25– 29.9 No. (%) |

BMI ≥30 No. (%) |

BMI 18.5– 24.9 No. (%) |

BMI 25– 29.9 No. (%) |

BMI ≥30 No. (%) |

BMI 18.5– 24.9 No. (%) |

BMI 25– 29.9 No. (%) |

BMI ≥30 No. (%) |

BMI 18.5– 24.9 No. (%) |

BMI 25– 29.9 No. (%) |

BMI ≥30 No. (%) |

BMI 18.5– 24.9 No. (%) |

BMI 25– 29.9 No. (%) |

BMI ≥30 No. (%) |

|

| Patients, No. (%) | 222 (37) |

231 (39) |

146 (24) |

85 (35) |

88 (37) |

67 (28) |

68 (33) |

88 (43) |

51 (25) |

102 (31) |

109 (33) |

120 (36) |

143 (45) |

107 (33) |

70 (22) |

74 (33) |

88 (40) |

59 (27) |

| Age, Mean, y (range) | 52 (18–91) |

56 (22–82) |

56 (30–82) |

51 (23–85) |

59 (29–88) |

55 (25–78) |

53 (24–83) |

60 (31–87) |

60 (34–80) |

57 (18–86) |

63 (34–86) |

63 (22–86) |

49 (17–86) |

56 (22–84) |

53 (31–78) |

55 (23–83) |

60 (24–88) |

56 (32–88) |

| Male, No. (%) | 109 (49) |

156 (68) |

82 (56) |

40 (47) |

59 (66) |

44 (66) |

41 (60) |

64 (73) |

33 (65) |

58 (57) |

70 (64) |

83 (69) |

70 (49) |

73 (68) |

31 (44) |

38 (51) |

66 (75) |

36 (61) |

| Stage, No. (%) | ||||||||||||||||||

| III/M1a/M1b | 71 (32) |

81 (35) |

59 (40) |

34 (40) |

34 (39) |

32 (48) |

17 (25) |

38 (43) |

26 (51) |

19 (19) |

32 (29) |

40 (33) |

42 (29) |

29 (27) |

31 (44) |

24 (32) |

37 (42) |

33 (56) |

| M1c | 151 (68) |

150 (65) |

87 (60) |

61 (60) |

54 (61) |

35 (52) |

51 (75) |

50 (57) |

25 (49) |

81 (79) |

76 (70) |

80 (67) |

101 (71) |

78 (73) |

39 (56) |

50 (68) |

51 (58) |

26 (44) |

| LDH >ULN, No. (%)b | 78 (36) |

79 (44) |

48 (33) |

45 (46) |

41 (47) |

26 (40) |

26 (38) |

31 (35) |

18 (25) |

40 (39) |

38 (35) |

39 (32) |

68 (48) |

44 (41) |

23 (33) |

37 (50) |

36 (41) |

23 (39) |

| ECOG PS, No. (%) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 159 (72) |

168 (73) |

103 (70) |

65 (77) |

72 (82) |

43 (64) |

46 (68) |

65 (74) |

35 (69) |

60 (59) |

64 (59) |

72 (60) |

95 (66) |

77 (72) |

46 (66) |

55 (74) |

63 (72) |

38 (64) |

| ≥1 | 61 (28) |

62 (27) |

43 (30) |

19 (22) |

15 (17) |

24 (36) |

22 (32) |

23 (26) |

16 (31) |

41 (40) |

45 (41) |

48 (40) |

48 (34) |

30 (28) |

24 (34) |

19 (26) |

25 (28) |

21 (36) |

| Mutation, No. (%)b | ||||||||||||||||||

| BRAF mutant | 222 (100) |

231 (100) |

146 (100) |

85 (100) |

88 (100) |

67 (100) |

– | – | – | 34 (33) |

32 (29) |

34 (28) |

143 (100) |

107 (100) |

70 (100) |

– | – | – |

| V600E | 201 (91) |

192 (83) |

129 (88) |

61 (72) |

62 (70) | 44 (66) |

– | – | – | – | – | – | 132 (92) |

94 (88) |

62 (89) |

– | – | – |

| Other V600 | 21 (9) |

39 (17) |

17 (12) |

6 (7) |

10 (11) |

8 (8) |

– | – | – | – | – | – | 8 (5) | 10 (9) | 5 (7) | – | – | – |

| NRAS mutant | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 24 (24) |

21 (19) |

18 (15) |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| WT | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 37 (36) |

50 (46) |

67 (57) |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

BMI= Body Mass Index. D+T= dabrafenib and trametinib cohort. ECOG PS=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status. IPI= Ipilimumab + dacarbazine cohort. LDH=lactate dehydrogenase. PD-1/PD-L1= anti-PD-1 and anti-PDL1 antibody cohort. V+C= vemurafenib and cobimetinib cohort. ULN= upper limit of normal. WT= wild type.

Data missing for 3 patients in PD1/PDL1 cohort

Data missing for 2 patients in D+T cohort, 3 patients in V+C cohort, 2 patients in PD1/PDL1 cohort, and 1 patient in CA184-024 cohort.

Data missing for 3 patients in D+T cohort, 2 patients in V+C cohort, 1 patient in PD1/PDL1 cohort

Data missing for 14 patients in PD1/PDL1

With a median follow-up of 9.3 months (IQR 5.1-21.2) for PFS, there were 386 events. The median PFS was 9.6 months (95% CI 9.0-12.1) for normal BMI, 11.0 months (9.2-14.9) and 15.7 (11.0-20.4) months for obese patients treated with D+T (Figure 1) with a significant association observed between obesity and improved PFS (Table 2). Analysis of BMI as a continuous variable demonstrated a dose-dependent inverse relationship between BMI and PFS that extended through morbid obesity (appendix p 3).

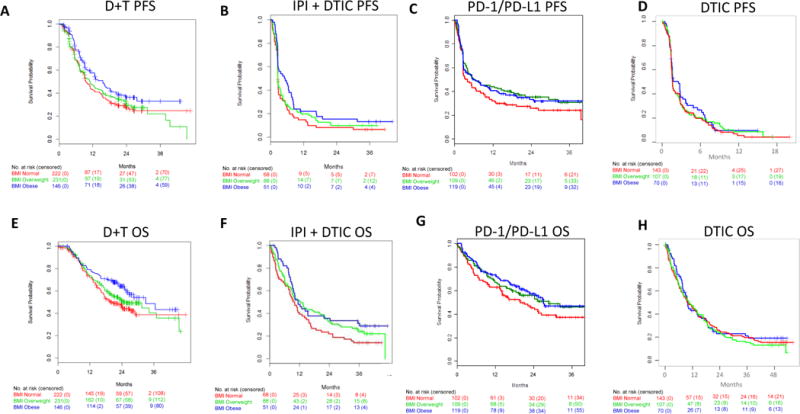

Figure 1. Progression-free survival and overall survival by BMI in metastatic melanoma patients treated with targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or chemotherapy.

Progression-free survival (PFS) in metastatic melanoma patients treated with a) dabrafenib + trametinib (D+T), b) Ipilimumab (IPI) + dacarbazine (DTIC) c) anti-PD-1/PD-L1, and d) dacarbazine (DTIC) chemotherapy. Overall survival (OS) in metastatic melanoma patients treated with e) dabrafenib + trametinib (D+T), f) Ipilimumab (IPI) + dacarbazine (DTIC) g) anti-PD-1/PD-L1, and h) dacarbazine (DTIC) chemotherapy. Red lines, normal BMI; Green lines, overweight BMI; Blue lines, obese BMI.

With a median follow-up of 20.9 months (IQR 10.5-24.8), there were 282 deaths. The median OS was 19.8 months (95% C 17.3-29.0) for normal BMI, 25.6 months (20.2-NR) for overweight, and 33.0 months (26.7-NR) months for obese patients treated with D+T, with a 37% decrease in risk of death among obese as compared to normal BMI patients (Figure 1 and Table 2). In multivariable-adjusted analyses incorporating clinicopathological factors previously associated with outcomes with D+T (age, sex, stage, LDH, BRAFV600 mutation type, ECOG PS, sum of target lesion diameters, number of disease sites, and prior adjuvant therapies)4, obese patients had significantly improved PFS [(HR and 95% CI 0.75 (0.57-0.99)] and OS [0.59 (0.43-0.82); Table 2] compared to normal BMI patients. We also examined the possible contribution of metabolic syndrome-related medication use, including metformin, beta blockers, aspirin, and statins. Following adjustment for concomitant medication use, obesity remained strongly associated with improved OS while the association with PFS was slightly attenuated (appendix p 3]. Clinical response rates with D+T were modestly increased in obese patients (appendix p 4-5).

With a median follow-up of 21.2 months (IQR 10.5-32.7) in the V+C cohort, there were 132 deaths and 170 PFS events out of 240 patients. Obese patients treated with V+C had improved PFS and OS, with very similar effects to those observed in the D+T cohort (Table 2, appendix p6). Following adjustment for clinical prognostic factors in this smaller cohort (age, gender, stage, LDH, BRAF mutation, ECOG performance status), the overall effects were minimally changed but statistical significance was lost (Table 2)]. Cobimetinib pharmacokinetic (PK) data available for this cohort demonstrated no significant differences in serum drug concentrations between BMI groups (appendix p 7).

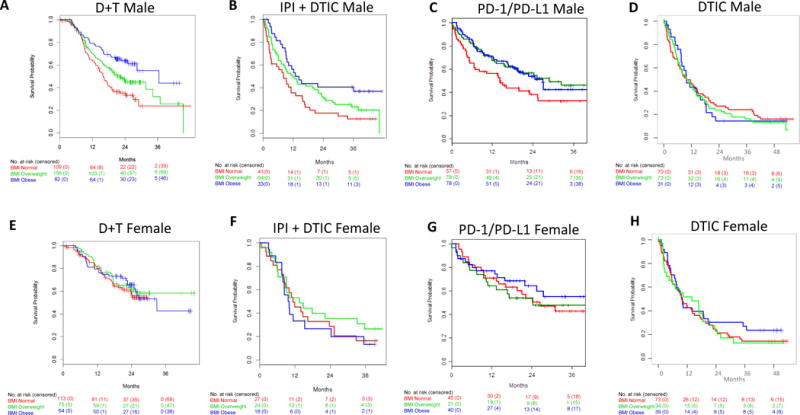

As female sex was previously shown to be independently associated with improved survival in the D+T cohort,4 and as there were sex differences in BMI distribution (Table 1), we assessed associations in men and women separately [p for interaction = 0.56 and 0.02 for PFS and OS, respectively (Table 2)]). These analyses showed that obesity was associated with improved PFS and OS in male patients treated with D+T. Median PFS and OS were 7.4 (95%CI 7.2-10.0) and 16.0(14.1-19.2) months respectively for normal BMI males, 10.1(8.1-12.1) and 21.3(18.1-27.0) months for overweight males, and 12.8 (9.1-20.4) and 36.5 (28.4-NR) months for obese males (Figure 2 and appendix p 8). Differences in OS remained significant after adjustment for other prognostic features (HR and 95% 0.44 (0.29-0.69) Table 2)]. These differences were marked, as the 2-year OS rate for obese males was 64% (95% CI 53%-74%) compared to 35% (26%-44%) for normal BMI males (appendix p 4). Obesity was also associated with a 2.3-fold higher response rate in males (appendix p 4-5)]. In contrast, there were no significant differences in PFS, OS, or response rates by BMI in female patients treated with D+T (Figure 2; Table 2; appendix p 4, 5, and 8). Similar differences by sex were observed in patients treated with V+C [p for interaction =0.06 and 0.44 for PFS and OS, respectively (Table 2 and appendix p 6)]. Obesity was associated with markedly improved PFS and OS in male patients, but statistical significance was lost following consideration of other prognostic factors in this smaller cohort (Table 2). No significant associations of BMI with outcomes were detected in female patients (Table 2).

Figure 2. Overall survival by BMI and sex.

Overall survival (OS) in male metastatic melanoma patients treated with a) dabrafenib + trametinib (D+T), b) Ipilimumab (IPI) + dacarbazine (DTIC) c) anti-PD-1/PD-L1, and d) dacarbazine (DTIC) chemotherapy. OS in female metastatic melanoma patients treated with e) dabrafenib + trametinib (D+T), f) Ipilimumab (IPI) + dacarbazine (DTIC) g) anti-PD-1/PD-L1, and h) dacarbazine (DTIC) chemotherapy. Red lines, normal BMI; Green lines, overweight BMI; Blue lines, obese BMI.

Immunotherapy cohorts

To determine if the association of obesity with improved outcomes was specific to targeted therapy, we analyzed the association of BMI with outcomes in patients treated with IPI + DTIC or with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy. BMI distributions of both immunotherapy cohorts were similar to the targeted therapy cohorts. Patients with higher BMI were again older and more likely to be male, and in the IPI + DTIC cohort also less likely to have M1C disease (Table 1 and appendix p 9). With a median follow-up of 28.7 months (IQR 2.5-36.6) for PFS, there were 176 events among 207 patients. With a median follow-up of 38.4 (IQR 35.6-40.4) months for OS, there were 158 deaths. Obesity was associated with improved PFS and OS compared to normal BMI in patients treated with IPI + DTIC (Table 2 and Figure 1). These associations remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, stage, and LDH [HR and 95% CI for PFS and OS respectively: 0.63 (CI 0.41-0.95) and 0.54 (0.34-0.86) Table 2].

Similar to targeted therapy, obesity in men was associated with significantly improved PFS [(multivariable-adjusted HR and 95% CI 0.55 (0.32-0.93)] and OS [(0.40 (0.22-0.72)], with 2 year OS of 41% (95% CI 27%-62%) in obese males versus 18% (9%-35%) in normal BMI males (Table 2; appendix p 4). In contrast, BMI was not associated with either PFS or OS in females treated with IPI + DTIC (Table 2; Figure 2).

Among the 331 patients in the anti-PD1/PD-L1 cohort, with a median follow-up of 25.4 months (IQR 18.4-34.2) for PFS, there were 221 events. With a median follow-up of 24.1 (IQR 17.4-33.9) months for OS, there were 162 deaths. The median PFS and OS respectively for metastatic melanoma patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 were 3.8 (95% CI 2.8-8.1) and 19.9 (14.2-31.1) months for patients with normal BMI, 6.2(4.7-17.7) and 28.8 (18.6-NR) months for overweight, and 5.7 (3.0-13.3) and 27.2 (22.0-NR) months for obese (Figure 1), though these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2). Obesity, as compared to normal BMI, was again associated with significantly improved outcomes in males but not females treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 [p for interaction for PFS and OS, respectively=0.07 and 0.84 (Table2)]. Among obese versus normal weight male patients, the median PFS was 7.6 (95% CI 4.1-23.5) vs. 2.7 (2.7-6.8) months (appendix p 8). This coincided with a 30-40% lower risk of progression [PFS HR and 95% CI 0.62 (0.41-0.92)] and death [OS 0.62 (0.39-0.98)], though adjustment for other prognostic factors attenuated the findings in this retrospective cohort (Table 2). Overall, associations were of the same magnitude and consistent with those observed with IPI + DTIC. In contrast, in women, there were no significant BMI associations (Table 2, Figure 2, appendix p 8).

Chemotherapy cohorts

To explore whether obesity was predictive of response to highly active contemporary therapies or generally prognostic in metastatic melanoma, we examined the associations of BMI in metastatic melanoma patients treated with dacarbazine (DTIC) chemotherapy, a control arm in multiple RCTs with low activity in this disease.2,21 Among the 331 patients in the BRIM3 cohort, there were 257 PFS events and 245 deaths. Among the 221 patients in the CA 184-024, with a median follow-up of 28.5 months (IQR 0.4-36.2), there were 211 PFS events and with a median follow-up of 38.2 months (IQR 35.9-41.3), there were 196 deaths. BMI was not significantly associated with PFS or OS in either cohort examined (Table 2; Figure 1). Further, BMI was not significantly associated with outcomes in either males or females (Table 2, Figures 2 and 3, appendix p 8 and 10).

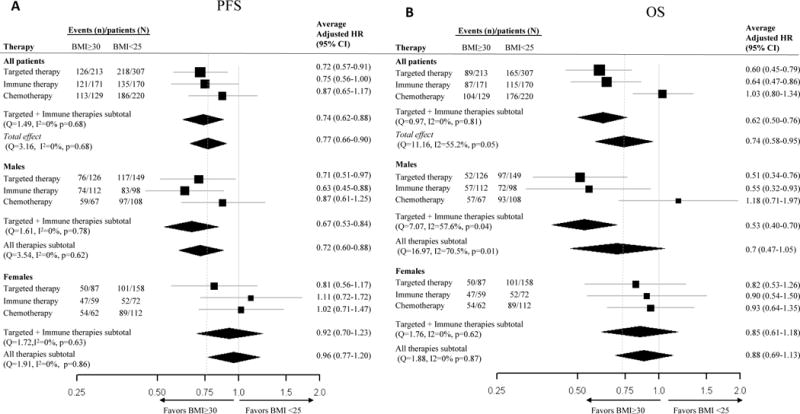

Figure 3. Forest plot of hazard ratios for PFS and OS for obese vs. normal BMI.

Forest plots of average adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for obese BMI in comparison to normal BMI by treatment class and sex for and a) progression-free survival (PFS) and b) overall survival (OS).

Adverse events

To explore whether differences in treatment tolerance could underlie the BMI effect, we determined rates of adverse events by BMI, sex, and grade in each cohort (appendix p 11-12). There was no evidence that adverse events occurred at a higher rate in normal BMI patients, supporting that the associations of obesity with improved survival are unlikely to be due to improved treatment tolerance.

Pooled analysis

In order to gain a better understanding of the prognostic importance of obesity in metastatic melanoma patients and the modifying effects of sex and treatment, we conducted pooled analyses using the methods of meta-analyses (Figure 3). Pooling the results from all cohorts, obesity, as compared to normal BMI, was associated with improved outcomes [average adjusted hazard ratio and 95% CI: 0.77 (0.66-0.90) and 0.74 (0.58-0.95) for PFS and OS, respectively]. However, we found significant heterogeneity in the prognostic effect of BMI by treatment type across the 6 cohorts for OS (Q=11.2, I2=55.2%, p<0.05) but not PFS, although similar trends were observed (Figure 3). Significant associations were observed with targeted therapy [average HR and 95% CI for OS: 0.60 (CI 0.45-0.79)] and immunotherapy [0.64 (0.47-0.86)] but not chemotherapy. We further examined BMI associations with outcomes in combined targeted and immune therapy cohorts [average HR and 95% CI for OS: 0.62 (0.50-0.76)], which significantly differed from pooled associations observed for chemotherapy (p for interaction=0.002). Although the protective effect of obesity for the combined targeted and immune therapy cohorts remained consistent for PFS [average HR and 95% CI 0.74: (0.62-0.88)], no significant interaction by treatment type was observed (p for interaction=0.34). Consistent with findings across individual targeted therapy and immunotherapy cohorts, we observed notable differences in BMI associations by sex in the combined analysis (p interaction for PFS and OS, respectively: 0.08 and 0.03). Within the combined targeted and immune therapy cohorts, the survival benefit of obesity was again restricted to males [average HR and 95% CI for PFS and OS 0.67 (0.53-0.84) and 0.53 (0.40-0.70), respectively; Figure 3]. BMI was not associated with outcomes in the pooled chemotherapy cohorts of male or female patients.

Discussion

Little is known about the clinical significance of obesity in advanced melanoma. Our analyses of multiple large, independent cohorts of metastatic melanoma patients treated with contemporary targeted and immune therapies unexpectedly revealed that obesity was associated with significantly improved outcomes. These associations appeared to be independent of traditional prognostic factors and concomitant medications, and they were not explained by differences in treatment tolerance or pharmacokinetics. Our findings further suggest that the relationship between BMI and outcomes in metastatic melanoma patients may vary by sex and treatment with a pronounced survival advantage observed among obese males treated with targeted and immune therapies. No significant associations between BMI and outcomes were observed among women, or in patients treated with chemotherapy within either individual cohorts or in the pooled analysis.

The current findings among metastatic melanoma patients contrast with prior data linking obesity with a slightly increased risk of developing melanoma,11,12 as well as a recent analysis of melanoma patients with clinically localized disease in which higher BMI was associated with worse survival.22 In aggregate, the findings support the presence of an “obesity paradox” across the spectrum of melanoma development, progression, and treatment response. This phenomenon, wherein higher BMI is associated with increased disease risk but confers a survival advantage in patients with established or advanced disease, has recently been described in other malignancies.7–9 Whether this inverse relationship is causal remains poorly understood.10 However, several features of the current study suggest a potential biological role of adiposity in metastatic melanoma patient survival. In other malignancies in which the obesity paradox has been observed, the survival advantage is often limited to overweight or only mildly obese patients.8 Though BMI is widely-used, it is an imperfect surrogate of adiposity and may misclassify body composition (fat versus muscle), particularly in the overweight range. In contrast, our data suggests a dose-effect of BMI with modestly improved outcomes in overweight patients and a strong, consistent survival advantage observed in obese patients. We also observed a nearly linear association between increasing BMI and PFS that extended to morbid obesity (where body composition is unlikely to be misclassified) in the large D+T cohort. In several malignancies in which obesity has been associated with a survival advantage, either the cancer or its treatment (i.e., chemotherapy) often cause weight loss, raising the possibility of reverse causality.10 As BMI was analyzed at a single time point (therapy initiation), we cannot rule out potential antecedent weight loss and future studies should include longitudinal BMI assessment. However, underweight BMI was rare (<2%) in these cohorts and such patients were excluded from analyses. Moreover, the BMI distribution of each cohort mirrored that of the general population, with over 60% of patients classified as overweight or obese. ECOG PS and albumin levels (PD-1/PDL-1 cohort) did not differ by BMI category, supporting that the normal BMI patients were not cachectic at baseline. Perhaps most importantly, the obesity survival advantage was specifically observed in patients treated with targeted and immune therapy, regimens which are not usually associated with the significant weight loss typical of chemotherapy-treated cohorts.

Our analyses also accounted for the potential contribution of traditional prognostic factors and the use of concomitant medications which may have anti-cancer activity, including metformin, statins, beta blockers, and aspirin. To interrogate other potential causes of the observed differences, we also examined rates of adverse events and available pharmacokinetic data (cobimetinib). These analyses again showed no significant differences by BMI category, supporting that treatment tolerance and drug exposure are unlikely to explain the observed associations. Differences in drug absorption are also an unlikely cause given that associations were seen in cohorts of patients treated with agents given orally at a fixed dose (targeted therapies) and with agents using weight-based intravenous dosing (immunotherapies). The associations of BMI with outcomes in patients treated with immunotherapy should be evaluated again in future cohorts of patients treated with flat-dosing regimens of these agents, which are now generally used.

The strength and consistency of these associations support the need for focused investigations into their biological basis. The significant interactions between BMI, sex and therapy in the pooled analyses are provocative and hypothesis-generating into potential mechanisms. Although targeted therapy and immunotherapy are fundamentally different treatment modalities, cross-talk between oncogenic signaling pathways and the anti-tumor immune response has been implicated in response and resistance to both treatments in melanoma.19,23,24 Though the impact of obesity-associated inflammation on carcinogenesis has been well-studied, the impact of energy balance on the anti-tumor immune response has not been examined to date and should be investigated as a potential explanation underlying the observed interaction between BMI and both targeted and immune therapy. A recent study in renal cell carcinoma in which high BMI was associated with improved outcomes with targeted therapy found that alterations in fatty acid metabolism were associated with both obesity and outcomes.9 Given emerging evidence implicating tumor and immune cell metabolism in melanoma therapeutic response,25 the relationship between tumor metabolism and clinical metabolic phenotype should also be explored in this disease. Analyses are ongoing examining the molecular, immunologic, and metabolic correlates of obesity in melanoma. However, the striking differences in BMI and outcome associations by sex observed here also suggest a potential hormonal mediator of the BMI effects.

In male patients, obesity was associated with a near doubling in survival whereas no significant associations were observed in females. Female sex has long been recognized as a predictor of improved outcomes in melanoma.20 Intriguingly, our data suggests that obesity could confer a similar survival advantage among male metastatic melanoma patients treated with targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Obesity in males results in higher levels of circulating estradiol as adipose tissue aromatase activity converts androgens to oestrogen compounds.26 Interestingly, a previous RCT of DTIC +/− tamoxifen, a selective oestrogen receptor modulator, showed no benefit in metastatic melanoma patients overall. However, higher BMI in men and postmenopausal status in women was predictive of benefit from the addition of tamoxifen to chemotherapy, but not with chemotherapy alone, in this trial.27 Though menopausal status was not available for the cohorts in the current analysis, this interaction should be investigated in future studies and would further strengthen the hypothesis of a hormonal mediator driving the observed associations. Melanoma lacks significant oestrogen receptor alpha (ERα) expression, the receptor responsible for the proliferative effects of oestrogen on breast cancer. However, prior reports have demonstrated high oestrogen-receptor beta (ERβ), which may have anti-proliferative activity,28 in primary melanoma,29 as well as non-classical oestrogen signaling through a G-protein coupled oestrogen receptor (GPER).30 Recent studies suggest that GPER signaling in melanocytes may regulate their differentiation status,30 which has been implicated in resistance to both targeted and immune therapy in this disease. Moreover, the effect of estrogen on immune function has been well-studied in the context of sex disparities in rates of autoimmune disease, and immune response to vaccines and pathogens, and is another potential mechanism by which hormones could mediate the observed BMI effect.

The pooled analysis has several limitations and should be viewed as exploratory given that there were only 6 cohorts, as meta-analysis methodology is problematic with small numbers of studies. As further data on the associations between BMI and outcomes in melanoma becomes available, full meta-analyses should be conducted. Within the pooled analysis, we observed significant interactions between BMI, therapy, and sex, which support the associations observed within the individual cohorts in which BMI was associated with improved outcomes in males treated with targeted and immune therapy but not associated with outcomes in females or in patients treated with chemotherapy. However, even with the pooled analysis, fewer females (particularly obese females) across the cohorts could have limited statistical power to detect associations in this group. Moreover, the current analysis could be underpowered to detect the association between BMI and outcomes in a treatment that has a low response rate (i.e., chemotherapy). However, the striking survival advantage observed among obese men in the IPI +DTIC cohort would argue against this given that the response rate to ipilimumab (10-15%) is only marginally higher than that observed with chemotherapy.

In conclusion, obesity is associated with improved outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma. Our analysis of multiple independent cohorts and our pooled analysis support that these effects may vary by treatment and sex, with the strongest associations observed in males treated with either targeted or immune therapy. The use of pooled data from the D+T arms of multiple clinical trials, which had previously been analyzed for clinical prognostic factors, allowed for robust covariate adjustment and examination of RECIST response rates in addition to survival.4 As survival data matures from the PD1 immunotherapy trials (FDA approvals 2014) we will validate the findings of the multi-institutional retrospective PD1 cohort presented here with clinical trial level data. The association of BMI and outcomes in other malignancies in which targeted and/or immune therapies are approved should also be examined. The magnitude of the observed differences in OS observed in male patients was quite large, comparable to or larger than differences seen in several registration trials in metastatic melanoma.1,31 These findings support the need to consider sex and BMI as stratification factors in trials, and to investigate the biological mechanisms underlying these unexpected and provocative results.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

To our knowledge, there have been no prior studies examining the association of BMI with outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma. We searched PubMed up to August 15, 2017 for articles with the terms “melanoma,” and “body mass index” and identified 149 articles. Of these, there were 14 analyses examining the association between body mass index and risk of melanoma, including 12 primary studies and two meta-analyses. Overall, the studies support that elevated BMI is associated with a slightly increased risk of melanoma in men, but not in women. Two studies found that increased BMI is associated with increased primary melanoma thickness. Only two studies have reported on the association between BMI and outcomes in melanoma. We recently demonstrated that increased BMI was associated with worse survival in patients with surgically resected melanoma. A report of a clinical trial of dacarbazine +/− tamoxifen in metastatic melanoma contained an exploratory analysis suggesting that increased BMI in men and post-menopausal females was associated with benefit from the addition of tamoxifen to dacarbazine. We did not identify any studies that examined the association of BMI with outcomes in melanoma patients treated with targeted and immune therapies

Added value of this study

This study examined the association of BMI with outcomes in 6 independent cohorts, which together included >1900 patients with metastatic melanoma. The cohorts included several randomized clinical trials that led to FDA approval of immune and targeted therapies, as well as their chemotherapy control arms. This analysis showed that obesity was associated with significantly improved survival in metastatic melanoma, an association that has not been identified previously. This association was independent of traditional prognostic factors. Further, the survival benefit of obesity was restricted to patients treated with targeted and immune therapies and was not detected in chemotherapy cohorts. Finally, we identified a novel sex difference, as BMI was associated with marked improvements in survival in obese males compared to their normal BMI counterparts, but not in females.

Implications of all the available evidence

The results have implications for the design of future clinical trials for metastatic melanoma patients. The magnitude of the effects, as well as the novel interaction observed between BMI, sex, and treatment suggest possible underlying mechanisms which should be examined further.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support:

The study was supported by philanthropic support from the MDACC Melanoma Moonshot Program, the MDACC Center Melanoma SPORE (NIH/NCI P50CA221703), and the Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation. JLM was initially supported for this work by an ASCO/CCF Young Investigator Award and an NIH T32 Training Grant CA009666, and has ongoing support through an ASCO/CCF Career Development Award and a MDACC Center Melanoma SPORE Developmental Research Program Award, and an. CRD and KH are supported by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016672). PBC is funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. JEL is supported by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Various Donors Melanoma and Skin Cancers Priority Program Fund; the Miriam and Jim Mulva Research Fund; the McCarthy Skin Cancer Research Fund and the Marit Peterson Fund for Melanoma Research GVL is supported by the University of Sydney Medical Foundation and NHMRC Australian Research Fellowship. DBJ is supported by NIH/NCI K23 CA204726. AMM is supported by a Cancer Institute NSW Fellowship. MAD is supported by NIH/NCI (1 R01 CA187076-01).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

JLM, CRD, and KRH report no disclosures. CM has received consultant fees from Novartis. DYW, RRR, JJP, LEH, and CS report no disclosures. MW is an employee of Roche/Genentech and is a stockholder in Roche and ARIAD Pharmaceuticals. SL is a former employee of Novartis and a current employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. DYL and MK are employees of Novartis. MM, KEB, and SMR report no disclosures. IR, LM, NB, and JH are employees of Genentech and LM and NB are also shareholders of Genentech. TSN reports no disclosures. AA is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. TH is an employee and shareholder of Novartis. MP, SL, and SF report no disclosures. JAW has received compensation for Speaker’s Bureau and honoraria from Dava Oncology, Bristol Myers Squibb and Illumina, and has served on advisory committees for GlaxoSmithKline, Roche/Genentech, Novartis, Astra Zenneca. JEG is on advisory boards for Merck and Castle Biosciences. JEL reports no disclosures. PH has received fees from Dragonfly, Immatics, Iovance, Sanofi, and GSK and non-financial support from MedImmune. PBC is a consultant for Daiichi, Hoffman-LaRoche, Genentech, and Merck, has received research support from Pfizer and BMS, and is a stockholder in Rgenix. KTF is a consultant to Novartis. JAS has received fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, Merck, Genentech, and Array. DS is a consultant for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Leo Pharma, Roche, Merck/MSD, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. JJG is on the advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Amgen, Merck/Pfizer, and Pierre Fabre. KTF reports no disclosures. DW is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. YY is an employee and shareholder of Roche/Genentech. EM is an employee and shareholder of Roche/Genentech. JJL is an employee and shareholder of Novartis. MSC is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Novartis and Amgen. AR is on the advisory board of Roche/Genentech, Novartis, Merck, Takeda, and Pierre-Fabre. JMK has received personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche/Genentech, Novartis, EMD Serono, Merck, Array Biopharma, Amgen, SolaranRX, Inc, and Checkmate Pharmaceuticals and research funding from Merck and Prometheus. GVL is a consultant for Amgen, Array, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck MSD, Novartis, Pierre-Fabre, and Roche/Genentech. DBJ is on advisory boards for BMS and Genoptix and receives research funding from Incyte. AM is on the advisory board for Novartis, MSD, Chugai, and Pierre-Fabre and has received honoraria from BMS and Roche. MAD has served on advisory boards for Novartis, Roche/Genentech, GSK, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, and Vaccinex and is the principal investigator on research funding to MDACC from Roche/Genentech, GSK, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck, and Astrazeneca.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Drs. McQuade and Davies had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study design: McQuade, Davies

Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation: All authors

Writing: McQuade, Daniel, Davies

Critical review and revision of the manuscript: All authors

Additional Contributions: We thank the following for data collection: Sergine Lo, MD, Alexander Gumiski, MD; Kazi Nahar, MD.

References

- 1.Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1867–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus Dacarbazine for Previously Untreated Metastatic Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(26):2517–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in Previously Untreated Melanoma without BRAF Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(4):320–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long GV, Grob JJ, Nathan P, et al. Factors predictive of response, disease progression, and overall survival after dabrafenib and trametinib combination treatment: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1743–54. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. Body Fatness and Cancer - Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenlee H, Unger JM, LeBlanc M, Ramsey S, Hershman DL. Association between Body Mass Index and Cancer Survival in a Pooled Analysis of 22 Clinical Trials. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention. 2017;26(1):21–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroenke CH, Neugebauer R, Meyerhardt J, et al. Analysis of Body Mass Index and Mortality in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Using Causal Diagrams. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1137–45. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albiges L, Hakimi AA, Xie W, et al. Body Mass Index and Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Clinical and Biological Correlations. J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lennon H, Sperrin M, Badrick E, Renehan AG. The Obesity Paradox in Cancer: a Review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18(9):56. doi: 10.1007/s11912-016-0539-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sergentanis TN, Antoniadis AG, Gogas HJ, et al. Obesity and risk of malignant melanoma: a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(3):642–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skowron F, Berard F, Balme B, Maucort-Boulch D. Role of obesity on the thickness of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jdv.12515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang S, Wang Y, Dang Y, et al. Association between Body Mass Index, C-Reactive Protein Levels, and Melanoma Patient Outcomes. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(8):1792–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang S, Wang Y, Sui D, et al. C-reactive protein as a marker of melanoma progression. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(12):1389–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gogas H, Trakatelli M, Dessypris N, et al. Melanoma risk in association with serum leptin levels and lifestyle parameters: a case-control study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(2):384–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazar I, Clement E, Dauvillier S, et al. Adipocyte Exosomes Promote Melanoma Aggressiveness through Fatty Acid Oxidation: A Novel Mechanism Linking Obesity and Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76(14):4051–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hursting SD, Berger NA. Energy balance, host-related factors, and cancer progression. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(26):4058–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.27.9935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gopal YN, Deng W, Woodman SE, et al. Basal and treatment-induced activation of AKT mediates resistance to cell death by AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in Braf-mutant human cutaneous melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(21):8736–47. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng W, Chen JQ, Liu C, et al. Loss of PTEN promotes resistance to T-cell mediated immunotherapy. Cancer Discovery. 2016;6(2):201–16. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joosse A, Collette S, Suciu S, et al. Sex Is an Independent Prognostic Indicator for Survival and Relapse/Progression-Free Survival in Metastasized Stage III to IV Melanoma: A Pooled Analysis of Five European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(18):2337–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang S, Wang Y, Dang Y, et al. Association between body mass index, C-reactive protein levels, and melanoma patient outcomes. J Invest Dermatol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frederick DT, Piris A, Cogdill AP, et al. BRAF Inhibition Is Associated with Enhanced Melanoma Antigen Expression and a More Favorable Tumor Microenvironment in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2013;19(5):1225–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen G, McQuade JL, Panka DJ, et al. Clinical, molecular, and immune analysis of dabrafenib-trametinib combination treatment for braf inhibitor–refractory metastatic melanoma: A phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gopal YNV, Rizos H, Chen G, et al. Inhibition of mTORC1/2 Overcomes Resistance to MAPK Pathway Inhibitors Mediated by PGC1α and Oxidative Phosphorylation in Melanoma. Cancer Research. 2014;74(23):7037–47. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider G, Kirschner MA, Berkowitz R, Ertel NH. Increased estrogen production in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;48(4):633–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem-48-4-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cocconi G, Bella M, Calabresi F, et al. Treatment of metastatic malignant melanoma with dacarbazine plus tamoxifen. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(8):516–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208203270803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marzagalli M, Casati L, Moretti RM, Montagnani Marelli M, Limonta P. Estrogen Receptor beta Agonists Differentially Affect the Growth of Human Melanoma Cell Lines. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Giorgi V, Gori A, Gandini S, et al. Oestrogen receptor beta and melanoma: a comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):513–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Natale CA, Duperret EK, Zhang J, et al. Sex steroids regulate skin pigmentation through nonclassical membrane-bound receptors. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.15104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2006–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.