Key Points

Question

What are the predictors and sources of variation of long-term acute care hospital (LTAC) vs skilled nursing facility (SNF) transfer among hospitalized older adults?

Findings

In this cohort study of 65 525 hospitalized older adults receiving a tracheostomy and being hospitalized in close proximity to an LTAC were the 2 strongest predictors of LTAC transfer. After adjusting for case-mix, differences between patients, hospitals, and regions explained 52%, 15%, and 33% of the variation in LTAC transfer, respectively.

Meaning

Half of the variation in LTAC vs SNF transfer is independent of patients’ illness severity or clinical complexity, and is explained by where the patient was hospitalized and in what region; given the higher expense associated with LTACs vs SNFs, greater attention is needed to define the optimal role of LTACs in the postacute care of older adults.

This cohort study examines factors associated with variation in acute care transfers to long-term acute care hospitals vs skilled nursing facilities among older patients.

Abstract

Importance

Despite providing an overlapping level of care, it is unknown why hospitalized older adults are transferred to long-term acute care hospitals (LTACs) vs less costly skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) for postacute care.

Objective

To examine factors associated with variation in LTAC vs SNF transfer among hospitalized older adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted this retrospective observational cohort study of hospitalized older adults (≥65 years) transferred to an LTAC vs SNF during fiscal year 2012 using national 5% Medicare data.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Predictors of LTAC transfer were assessed using a multilevel mixed-effects model adjusting for patient-, hospital-, and region-level factors. We estimated variation partition coefficients and adjusted hospital- and region-specific LTAC transfer rates using sequential models.

Results

Among 65 525 hospitalized older adults (42 461 [64.8%] women; 39 908 [60.9%] ≥85 years) transferred to an LTAC or SNF, 3093 (4.7%) were transferred to an LTAC. We identified 29 patient-, 3 hospital-, and 5 region-level independent predictors. The strongest predictors of LTAC transfer were receiving a tracheostomy (adjusted odds ration [aOR], 23.8; 95% CI, 15.8-35.9) and being hospitalized in close proximity to an LTAC (0-2 vs >42 miles; aOR, 8.4, 95% CI, 6.1-11.5). After adjusting for case-mix, differences between patients explained 52.1% (95% CI, 47.7%-56.5%) of the variation in LTAC use. The remainder was attributable to hospital (15.0%; 95% CI, 12.3%-17.6%), and regional differences (32.9%; 95% CI, 27.6%-38.3%). Case-mix adjusted LTAC use was very high in the South (17%-37%) compared with the Pacific Northwest, North, and Northeast (<2.2%). From the full multilevel model, the median adjusted hospital LTAC transfer rate was 2.1% (10th-90th percentile, 0.24%-10.8%). Even within a region, adjusted hospital LTAC transfer rates varied substantially (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC], 0.26; 95% CI, 0.23-0.30).

Conclusions and Relevance

Although many patient-level factors were associated with LTAC use, half of the variation in LTAC vs SNF transfer is independent of patients’ illness severity or clinical complexity, and is explained by where the patient was hospitalized and in what region, with far greater use in the South. Even among hospitals in regions with similar LTAC access, there was considerable variation in LTAC use. Given the higher expense associated with LTACs vs SNFs, greater attention is needed to define the optimal role of LTACs in the postacute care of older adults.

Introduction

The use of postacute care by hospitalized older adults has increased by 50% over the past 2 decades, and accounts for the single largest increase in Medicare spending. Postacute care is the largest driver of variation, accounting for 73% of the geographic variation in Medicare spending. Long-term acute care hospitals (LTACs) are the fastest growing segment of postacute care. Long-term acute care hospitals now account for more than 140 000 hospitalizations and $5.5 billion in Medicare spending annually, which is approximately one-fifth of the spending on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). Despite the rapid growth, the role of LTACs in postacute care is unclear. Long-term acute care hospitals are defined by an average length of stay of at least 25 days and not by specific patient criteria. As such, LTACs care for individuals with a wide spectrum of complex and prolonged illness.

Before the growth in LTACs, many hospitalized older adults who were too sick to go home were instead discharged to SNFs for postacute care. More than 90% of SNFs care for older adults who meet the “clinically complex” or “special care” resource utilization group designation, which includes complex wounds, kidney failure, and severe infections, that are also considered indications for LTAC admission. Given the higher intensity of care provided in LTACs, such as lower nurse-to-patient ratios, LTACs are reimbursed at 3- to 12-fold higher rates than SNFs for equivalent diagnoses. Thus, understanding why patients are transferred to LTACs rather than SNFs has important policy implications for accountable care organizations (ACOs) and payers.

In this study, we sought to examine the patient-, hospital-, and region-level factors associated with transferring hospitalized older adults to an LTAC vs an SNF, and quantify how much of the variation in LTAC use is explained by each level. We hypothesize that a large degree of the variation in LTAC use will be explained by the hospital and region, independent of clinical severity.

Methods

Study Design and Cohort

We conducted an observational cohort study using national 5% Medicare data from 2010 to 2012. We included fee-for-service beneficiaries discharged from an acute care hospital and subsequently transferred to an LTAC or SNF on the same or next day using an adjacent claims algorithm during fiscal year 2012. Long-term acute care hospitals and SNFs were identified using the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provider numbers, which are based on Medicare certification. Long-term acute care hospitals were confirmed with manual review of facility names and Internet searches if the facility type was uncertain. Hospital characteristics were obtained from CMS Provider of Services and Impact Files. Regions were defined as the hospital referral region (HRR).

Statistical Analysis

Predictors of LTAC vs SNF Transfer

To ascertain independent predictors of LTAC transfer, we developed a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression model to account for clustering of patients in hospitals and hospitals in HRRs. Model diagnostics suggested excellent fit (C statistic, 0.95; < 0.7% absolute difference between observed and predicted LTAC transfer rates for the lowest 9 deciles of predicted risk). See eMethods 1 and eTables 1, 2, and 3 in the Supplement for details on predictors and analyses.

Variation of LTAC vs SNF Transfer

To quantify the variation explained at the patient, hospital, and region level, we estimated variance partition coefficients (VPCs) using sequential multilevel models. We first developed a case-mix only model that included patient-level predictors from our final model to estimate how much of the variation was owing to regions, independent of patient differences. We then sequentially included hospital- and region-level predictors into the model to estimate VPCs. From the final model, we created a variation profile graph showing adjusted hospital LTAC transfer rates and a scatterplot illustrating hospital variation within HRRs. We restricted these analyses to hospitals with 10 or more patients to enable more stable estimates. Finally, we estimated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to examine variation among hospitals’ transfer rates within the same HRR.

Sensitivity Analyses

We repeated our analyses among 2 subgroups that have more equipoise in the transfer decision: (1) patients hospitalized in HRRs with 1 or more LTAC; and (2) patients who did not receive prolonged mechanical ventilation or a tracheostomy (eMethods 2 in the Supplement).

The UT Southwestern institutional review board approved this study. We conducted analyses using Stata statistical software (version 14.2, Stata Corp), SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc), and ArcGIS (version 10.3, Esri Inc).

Results

We included 65 525 unique patients hospitalized in 3053 different hospitals across 304 HRRs (Table 1). A total of 3093 patients (4.7%) were transferred to an LTAC. There were many notable differences between the LTAC and SNF groups (Table 2), including receipt of tracheostomy (17% vs 0.2%) and distance to the nearest LTAC (41% hospitalized within 0-2 miles vs 19%).

Table 1. Study Flow Table.

| LTAC Claims | Exclusion Criteria | SNF Claims | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included | Excluded | Excluded | Included | |

| 4671 | Initial populationa | 90 359 | ||

| 4667 | 4 | Missing data in denominator file | 87 | 90 272 |

| 4418 | 249 | Did not have continuous Parts A and B in prior year | 2548 | 87 724 |

| 4266 | 152 | Had Part C≥1 months in prior year | 3362 | 84 362 |

| 4265 | 1 | Index acute care hospital was in Alaska or Hawaii | 181 | 84 181 |

| 4264 | 1 | Index acute care hospital missing provider number | 55 | 84 126 |

| 4234 | 30 | Index acute care hospital claim missing DRG | 425 | 83 701 |

| 3093b | 1141 | Not first eligible claim per patient in study period | 21269 | 62 432b |

Abbreviations: DRG, diagnosis-related group; LTAC, long-term acute care hospital; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Of 418 103 unique general acute care hospital claims of adults ages 65 or older during federal fiscal year 2012, 4671 and 90 359 were transferred to an LTAC or SNF respectively on the same or next day of hospital discharge.

Represents unique patients that are mutually exclusive between LTAC and SNF groups.

Table 2. Characteristics and Predictors of LTAC vs SNF Transfer Among Hospitalized Older Medicare Beneficiaries.

| Characteristica | LTAC (n = 3093) | SNF (n = 62 432) | Univariate ORb (95% CI) | Adjusted ORc (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Factors Prior to Hospitalization | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| 65-69 | 567 (18.3) | 5435 (8.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 70-74 | 694 (22.4) | 7881 (12.6) | 0.83 (0.73-0.94) | 0.87 (0.74-1.02) |

| 75-79 | 622 (20.1) | 10 418 (16.7) | 0.56 (0.49-0.64) | 0.76 (0.65-0.90) |

| 80-84 | 577 (18.7) | 13 775 (22.1) | 0.39 (0.34-0.44) | 0.62 (0.53-0.73) |

| ≥85 | 633 (20.5) | 24 923 (39.9) | 0.23 (0.20-0.26) | 0.51 (0.43-0.59) |

| Female | 1621 (52.4) | 40 840 (65.4) | 0.56 (0.52-0.61) | 0.79 (0.72-0.87) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 2337 (75.6) | 54 765 (87.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black | 516 (16.7) | 5284 (8.5) | 1.87 (1.66-2.10) | 1.33 (1.15-1.54) |

| Other | 240 (7.8) | 2383 (3.8) | 1.46 (1.24-1.73) | 1.29 (1.05-1.57) |

| Prior hospitalizations | ||||

| 0 | 1264 (40.8) | 35 522 (56.9) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1 | 785 (25.4) | 14 736 (23.6) | 1.47 (1.34-1.62) | 1.31 (1.17-1.48) |

| ≥2 | 1044 (33.8) | 12 174 (19.5) | 2.27 (2.07-2.49) | 1.59 (1.40-1.80) |

| Prior LTAC use | 222 (7.2) | 378 (0.6) | 5.78 (4.73-7.06) | 3.97 (3.12-5.06) |

| Prior SNF use | 530 (17.1) | 12 233 (19.6) | 0.77 (0.70-0.85) | 0.51 (0.44-0.58) |

| Wheelchair | 477 (15.4) | 6332 (10.1) | 1.41 (1.26-1.57) | 1.23 (1.07-1.42) |

| Home hospital bed | 313 (10.1) | 3201 (5.1) | 1.77 (1.54-2.02) | 1.19 (1.00-1.42) |

| Home oxygen | ||||

| None | 2420 (78.2) | 54 828 (87.8) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Transient (≥1 but <12 mo of use) | 447 (14.5) | 4846 (7.8) | 2.19 (1.95-2.46) | 1.49 (1.29-1.73) |

| Chronic (use for prior 12 mo) | 226 (7.3) | 2758 (4.4) | 2.02 (1.73-2.36) | 1.34 (1.11-1.62) |

| Patient Factors of Index Hospitalization | ||||

| Length of hospital stay,d days | 12 (7-19) | 6 (4-9) | 1.35 (1.33-1.36) | 1.09 (1.07-1.10) |

| Prolonged ICU stay (≥3 d) | 1855 (60.0) | 17 769 (28.5) | 4.64 (4.25-5.06) | 1.15 (1.02-1.29) |

| Primary diagnosis | ||||

| DRG resource intensity weight, per unit | 2.1 (1.5-5.5) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | 1.56 (1.53-1.58) | 1.07 (1.04-1.11) |

| DRG with an MCC designation | 1629 (52.7) | 20 285 (32.5) | 2.30 (2.13-2.49) | 1.65 (1.48-1.85) |

| Respiratory MDC | 481 (15.6) | 7464 (12.0) | 1.30 (1.16-1.45) | 1.64 (1.43-1.88) |

| Circulatory MDC | 367 (11.9) | 9189 (14.7) | 0.77 (0.70-0.86) | 0.70 (0.60-0.81) |

| Musculoskeletal MDC | 230 (7.4) | 17 633 (28.2) | 0.22 (0.19-0.25) | 0.59 (0.50-0.70) |

| Secondary diagnosese | ||||

| Respiratory failure | 1294 (41.8) | 7068 (11.3) | 7.14 (6.54-7.79) | 1.38 (1.21-1.58) |

| Sepsis | 986 (31.9) | 5370 (8.6) | 5.49 (5.01-6.03) | 1.77 (1.56-2.00) |

| Skin, soft-tissue, or joint infection | 454 (14.7) | 2897 (4.6) | 3.93 (3.48-4.44) | 2.35 (2.02-2.74) |

| Chronic skin ulcer | 655 (21.2) | 5859 (9.4) | 2.77 (2.51-3.07) | 1.88 (1.65-2.14) |

| Device, graft, implant complication | 230 (7.4) | 1424 (2.3) | 3.92 (3.33-4.62) | 1.41 (1.14-1.73) |

| Complication of care | 495 (16.0) | 3718 (6.0) | 3.67 (3.27-4.11) | 1.20 (1.02-1.40) |

| Delirium or dementia | 599 (19.4) | 18 099 (29.0) | 0.48 (0.43-0.52) | 0.71 (0.63-0.80) |

| Selected intensive treatments and procedures | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||

| None | 2163 (69.9) | 60 394 (96.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Transient (<96 h) | 234 (7.6) | 1357 (2.2) | 5.89 (4.92-6.99) | 1.41 (1.15-1.74) |

| Prolonged (≥96 h) | 696 (22.5) | 681 (1.1) | 51.0 (43.9-59.3) | 2.50 (1.98-3.17) |

| Tracheostomy | 520 (16.8) | 140 (0.2) | 248.5 (194-319) | 23.8 (15.8-35.9) |

| Total parenteral nutrition | 195 (6.3) | 686 (1.1) | 8.01 (6.60- 9.71) | 2.20 (1.73-2.80) |

| Central venous line | 991 (32.0) | 4307 (6.9) | 7.63 (6.93-8.41) | 2.01 (1.78-2.28) |

| Dialysis | 454 (14.7) | 2277 (3.6) | 4.56 (4.03-5.17) | 1.59 (1.36-1.87) |

| Excisional debridement | 101 (3.3) | 376 (0.6) | 7.89 (6.05-10.27) | 3.49 (2.55-4.78) |

| Hospital Factors | ||||

| For profit ownership | 708 (22.9) | 8350 (13.4) | 1.30 (1.11-1.52) | 1.36 (1.14-1.62) |

| Bed size (ORs per 50 beds) | 326 (201-526) | 313 (177-493) | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | 0.96 (0.95-0.98) |

| Disproportionate share index (ORs per 0.10)f | 0.29 (0.20-0.39) | 0.23 (0.17-0.32) | 1.21 (1.16-1.26) | 1.12 (1.07-1.18) |

| Regional Factors | ||||

| Linear arc distance to nearest LTAC, miles | ||||

| >42 | 100 (3.2) | 11 302 (18.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 18-42 | 231 (7.5) | 12 316 (19.7) | 2.00 (1.49-2.68) | 1.86 (1.34-2.58) |

| 7-18 | 502 (16.2) | 12 538 (20.1) | 4.11(3.11-5.44) | 4.03 (2.93-5.54) |

| 2-7 | 1006 (32.5) | 14 444 (23.1) | 6.74 (5.13-8.87) | 6.10 (4.45-8.36) |

| 0-2 | 1254 (40.5) | 11 832 (19.0) | 9.04 (6.88-11.9) | 8.40 (6.12-11.50) |

| State without Certificate of Need law | 1817 (58.7) | 22 065 (35.3) | 1.80 (1.38-2.36) | 1.54 (1.21-1.95) |

| LTAC supply, beds/100K persons (ORs per 5) | 10.8 (7.3-21.5) | 6.9 (2.6-11.4) | 1.40 (1.32-1.49) | 1.17 (1.10-1.23) |

| Median household income, per $10 000g | 5.2 (4.5-6.1) | 5.4 (4.8-6.2) | 0.76 (0.67-0.86) | 0.64 (0.57-0.71) |

| Medicare EOL PAC spending, per $1000 | 14.9 (11.5-19.2) | 12.3 (10.1-15.0) | 1.21 (1.16-1.26) | 1.10 (1.06-1.15) |

Abbreviations: DRG, diagnosis-related group; EOL, end of life; HRR, hospital referral region; ICU, intensive care unit; LTAC, long-term acute care hospital; MCC, major complication or comorbidity; MDC, Major Diagnostic Category; OR, odds ratio; PAC, postacute care; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Categorical data are shown as number (percentage), and numerical data are shown as median (interquartile range).

Unadjusted ORs are from univariable multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression models including random effects for hospital and region.

Adjusted ORs are from a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression model including all predictors listed in the Table.

Length of stay was Winsorized at 4 and 14 days based on functional form analysis using restricted cubic splines.

Categorized using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification Software.

Disproportionate share index is a measure of the share of low-income patients served by the hospital.

Median household income was obtained from the US Census Bureau and aggregated at the HRR level.

Predictors of LTAC vs SNF Transfer

The 2 strongest independent predictors of LTAC transfer were receiving a tracheostomy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 23.8; 95% CI, 15.8-35.9) and being hospitalized near an LTAC (0-2 miles vs >42 miles; aOR, 8.40; 95% CI, 6.12-11.50) (Table 2).

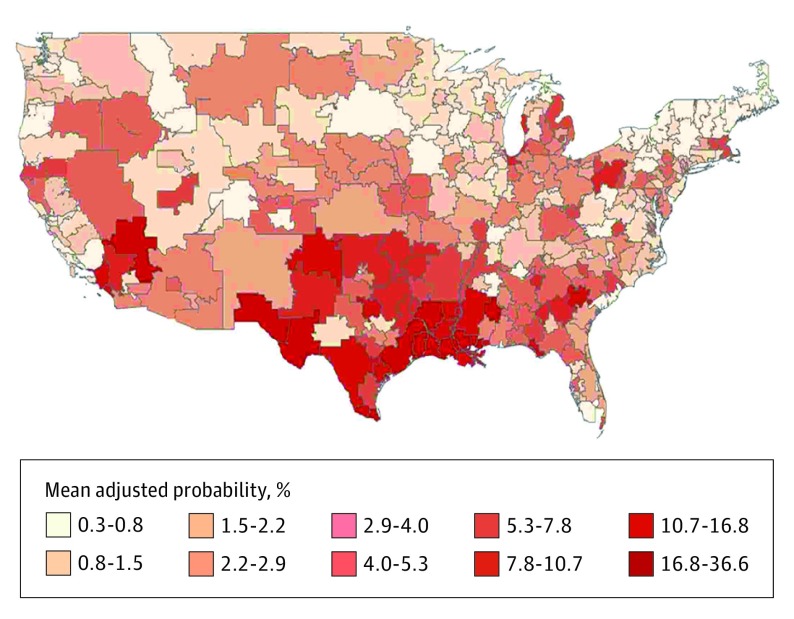

Regional Variation

After adjusting for case-mix, one-third of the variation (32.9%) was explained by differences between regions (Table 3), with a 16-fold difference in LTAC transfer rates between HRRs with the lowest 10th and highest 90th percentile transfer rate (Figure 1). Two-thirds of regional variation identified in the case-mix model was explained by region-level predictors included in our full model (proportion of variation explained: [32.9%-10.8%]/32.9% = 67.1%).

Table 3. Proportion of Variation in LTAC vs SNF Transfer Explained by Patients, Hospitals, and Regionsa.

| VPC | % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Case-Mix Only | Case-Mix + Hospital | Case-Mix + Hospital + Region (Full Model) | |

| Among patients | 52.1 (47.7-56.5) | 53.1 (48.6-57.6) | 73.6 (70.0-77.2) |

| Among hospitals | 15.0 (12.3-17.6) | 14.4 (11.8-17.0) | 15.6 (12.7-18.5) |

| Among regions | 32.9 (27.6-38.3) | 32.5 (27.1-37.8) | 10.8 (7.6-14.1) |

Abbreviations: LTAC, long-term acute care hospital; SNF, skilled nursing facility; VPC, variance partition coefficient.

Variance partition coefficients describe the proportion of variation explained by differences among patients, hospitals, and hospital referral regions. We conducted sequential multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression models to estimate the effect of adjusting for each successive level of predictors shown in Table 2. The case-mix only model adjusted for all patient-level predictors. The case-mix + hospital model further adjusted for the 3 significant hospital-level predictors. The full model adjusted for patient-, hospital-, and region-level predictors.

Figure 1. Adjusted LTAC Transfer Rate by Hospital Referral Region.

The mean adjusted long-term acute care hospital (LTAC) transfer probability (vs skilled nursing facility) by hospital referral region among hospitalized older adults was estimated from the case-mix only multilevel model adjusted for all patient-level predictors shown in Table 2. Hospital referral regions (n = 304) are defined as regional health care markets for tertiary medical care.

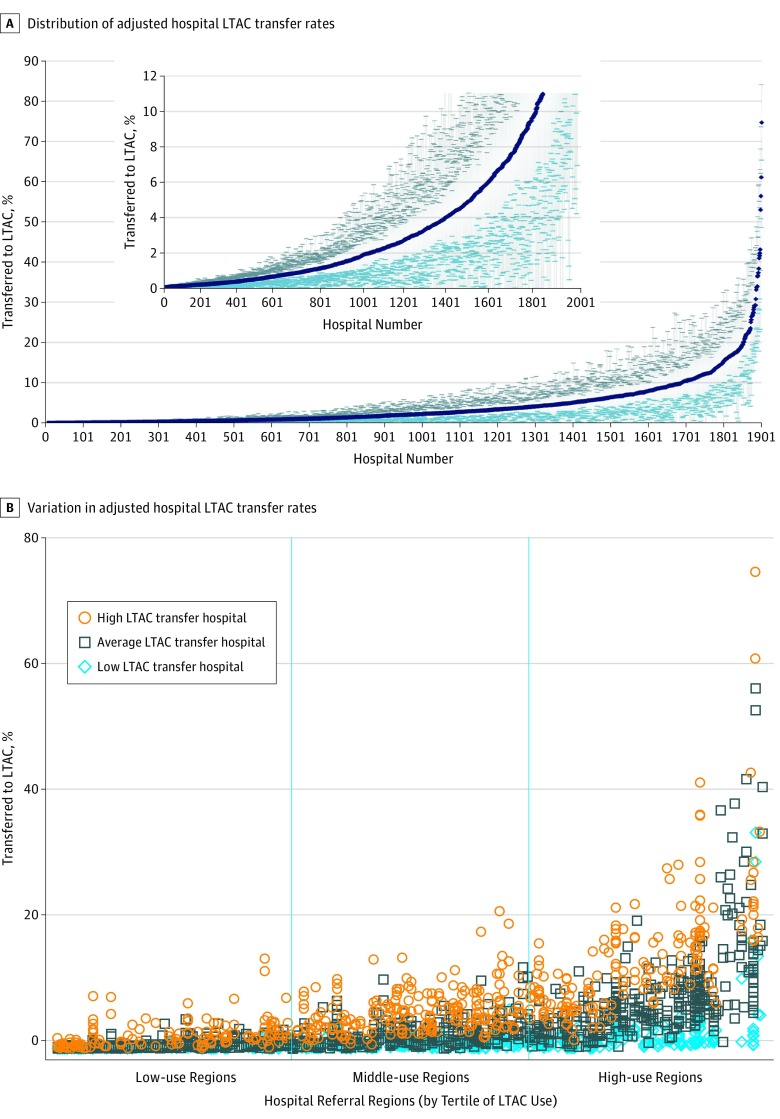

Hospital Variation

In our fully adjusted model, 15.6% of the variation in LTAC use was explained by differences between hospitals. The average adjusted transfer rate for hospitals varied considerably (Figure 2A). The median adjusted hospital LTAC transfer rate was 2.1% (10th-90th percentile, 0.24%-10.8%) with minimum and maximum values of 0.03% and 74.7%, respectively. Even within HRRs, adjusted hospital LTAC transfer rates varied substantially (ICC, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.23-0.30) (Figure 2B). In low-use HRRs there were hospitals with high adjusted transfer rates and in high-use HRRs there were hospitals with very low transfer rates.

Figure 2. Hospital Variation in LTAC Use.

Adjusted hospital LTAC transfer rates were estimated from the full multilevel model and shown for hospitals with 10 or more patients transferred to an LTAC or SNF (n = 1990). A, Hospitals are sorted in ascending order by their adjusted transfer rate and numbered. Mean hospital adjusted transfer rates are shown as dark blue points. The 95% CIs are shown as light gray vertical bars capped by light blue markers. The median hospital adjusted transfer rate was 2.1% (10th-90th percentile, 0.2%-10.8%). The inset shows a magnified version to better illustrate the variability of hospitals in the bottom 90th percentile of adjusted LTAC transfer rates. B, Hospitals are shown as individual markers within hospital referral regions (HRRs). The HRRs were sorted in ascending order by their case-mix adjusted LTAC transfer rates (as per Figure 1) and further categorized by tertiles of use. For each of the 304 HRRs, we estimated the HRR-specific 25th and 75th percentile values for adjusted hospital LTAC transfer rates. A low LTAC transfer hospital (blue diamond) was defined as having an adjusted transfer rate less than their HRR-specific 25th percentile hospital transfer rate. An average LTAC transfer hospital (black square) was defined as having between the 25th-75th percentile transfer rate. A high LTAC transfer hospital (orange circle) was defined as greater than the 75th percentile rate. All hospitals in HRRs with fewer than 4 hospitals were defined as average. This approach compares a hospital’s adjusted LTAC transfer rate with those of their peers within the same HRR.

Sensitivity Analyses

Findings were similar among patients not receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation (eTables 3-4 in the Supplement). Among patients hospitalized in HRRs with 1 or more LTAC, the effect size of distance to the nearest LTAC was attenuated, and differences between regions explained less of the variation in LTAC use (24.2% vs 32.9% for the full cohort). Otherwise, findings were comparable with those of our overall analysis.

Discussion

In this national study of postacute care use by hospitalized older adults, nearly half of the variation in LTAC use was independent of patients’ severity of illness or clinical complexity, and was instead related to the hospital and in what region they were located, with much greater use in the South than in the Pacific Northwest, North, and Northeast. Even among hospitals within the same region with similar potential LTAC access, there was substantial variation in LTAC use. Given that postacute care accounts for most of the geographic variation in Medicare spending and LTACs are the most expensive provider, our findings highlight opportunities to optimize the use of LTACs for patients who could not be effectively treated in less intensive settings, such as SNFs.

Our findings were similar to those found by Kahn and colleagues, who studied variation in LTAC use specifically after an intensive care unit (ICU) stay. Among this subset of patients, they identified significant hospital variation in LTAC use. Government-funded studies have also identified measures of patient severity (ie, tracheostomy) and LTAC bed supply as independent predictors of LTAC use. Finally, our findings of significant regional variation in LTAC use paralleled findings from prior studies on the geographic distribution of LTACs, where some regions have many and others few or none. However, we found that a considerable proportion of variation in LTAC use is owing to unexplained differences between regions, even after accounting for LTAC availability and other region-level factors.

Our study expands on prior research in several ways. First, we included all patients transferred to LTACs, and not just a subset of individuals surviving a critical illness in the ICU. Second, we simultaneously evaluated the independent contribution of patient-, hospital-, and regional-level predictors by conducting a 3-level hierarchical model, which previous studies did not do. This approach is essential given the large VPCs for hospitals and regions, and allowed us to parse out the variation after adjusting for key differences, which is important to help guide further research and policy. Third, we focused on the clinically relevant question of why hospitalized older adults are transferred to an LTAC vs an SNF, the principal postacute alternative. Previous studies examined predictors of LTAC transfer vs all other options combined, including discharge home, transfer to an alternate postacute care setting, or remaining hospitalized for the entire episode of care. There are many choices to optimize recovery, and the decision to transfer hospitalized older adults to LTACs vs each of these alternatives is likely to be unique.

Our study has several implications. For patients and clinicians, there may be more than 1 option to receive postacute care. Long-term acute care hospitals may improve outcomes by providing daily physician care, more favorable nurse-to-patient ratios, and more intensive interdisciplinary care, such as complex wound care, that are frequently unavailable in SNFs. Alternately, LTACs may lead to worse health outcomes. For example, patients treated in LTACs have higher rates of hospital-acquired infections than SNFs, including multidrug resistant pathogens. Further research is needed to assess the comparative effectiveness of LTACs vs SNFs in optimizing outcomes and functional recovery.

For insurance networks and ACOs, the substantial hospital variation in LTAC use represents an opportunity for cost savings by transferring similarly ill patients to less expensive SNFs for postacute care. Even in high-use regions, there are a considerable number of low LTAC transfer hospitals despite having similar access to LTACs. However, although SNFs may be less expensive than LTACs, the entire episode of care may be more costly if patients are rehospitalized after SNF transfer owing to an inability to care for these medically complex patients. The demand for LTACs is in part because of a perceived lack of adequately staffed, high-quality SNFs capable of providing complex nursing and medical therapy. By partnering with high-quality SNFs, payers and ACOs may be able to obviate the need for LTACs to fill this void among patients who do not require daily physician care.

For Medicare and other payers, our findings suggest that geography is destiny. The extremely large regional variation represents an opportunity to increase LTAC access in very low-use regions where patients with severe and complex illness may benefit from this higher level of postacute care, and in high-use regions to realign the incentives for using lower-cost SNFs. This includes both decreasing LTAC use by less-sick patients, and by ensuring adequate staffing and resources in SNFs to provide the necessary level of care for more medically complex patients. By October 2018, LTACs will receive a lower site-neutral payment for all patients who were not hospitalized in the ICU for at least 3 days or did not need prolonged mechanical ventilation prior to transfer. However, it is unclear whether this policy will result in indiscriminate vs clinically appropriate reductions in LTAC use, as patients who do not meet these criteria may be sicker and more complex in other ways.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, we studied older fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Although we cannot comment on privately insured, Medicare Advantage, or younger populations, fee-for-service beneficiaries account for two-thirds of national LTAC use. Second, even though we included many strong measures of advanced illness, complexity, functional impairment, and frailty, administrative data may not fully capture these differences among patients.

Conclusions

Half of the variation in transferring hospitalized older adults to LTACs vs SNFs is independent of patients’ illness severity and clinical complexity. Regional differences explain a third of the variation, with far greater use in the South. The considerable hospital variation in LTAC use, even among hospitals with similar LTAC access, suggests that insurance networks and ACOs have the potential to partner with low LTAC transfer hospitals and high-quality SNFs to develop more efficient networks. The increasing use and greater expense of LTACs, coupled with tremendous variation in use, mandate greater attention to understanding and defining its role in the postacute care of older adults recovering from acute illness.

eMethods 1. Predictors of LTAC vs SNF Transfer

eTable 1. Data Sources and Definitions for Predictors Included in Full Model

eMethods 2. Sub-Cohorts for Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 2. Model Performance of Full Multilevel Models

eTable 3. Predictors of LTAC use from Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 4. Variation in LTAC use from Sensitivity Analyses

eReferences.

References

- 1.Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post-acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):295-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenq GY, Tinetti ME. Post-acute care: who belongs where? JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):296-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Patient and hospitalization characteristics associated with increased postacute care facility discharges from US hospitals. Med Care. 2015;53(6):492-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(5):864-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in health care spending in the United States: insights from an Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1227-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Medicare Payment Policy: Long-Term Acute Care Hospital Services Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eskildsen MA. Long-term acute care: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):775-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalton K, Kandilov AM, Kennell DK, Wright A. Determining Medical Necessity and Appropriateness of Care for Medicare Long-term Care Hospitals Falls Church, VA: Kennell and Associates Inc and RTI International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Medicare Payment Policy: Long-term Acute Care Hospital Services. Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Medicare Payment Policy: Skilled Nursing Home Services. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS Medicare program; prospective payment system and consolidated billing for skilled nursing facilities for FY 2012. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2011;76(152):48486-48562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandilov AM, Dalton K. Utilization and Payment Effects of Medicare Referrals to Long-term Care Hospitals. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, Moody J, Kahn JM, Asch DA. The structure of critical care transfer networks. Med Care. 2009;47(7):787-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn JM, Benson NM, Appleby D, Carson SS, Iwashyna TJ. Long-term acute care hospital utilization after critical illness. JAMA. 2010;303(22):2253-2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 16.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, et al. . A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(4):290-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Census Bureau 2011. American Community Survey 5-year Estimates, Table S1901: Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2011 Inflation–adjusted Dollars). http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/con-certificate-of-need-state-laws.aspx. Accessed December 15, 2016.

- 18.Kahn JM, Werner RM, Carson SS, Iwashyna TJ. Variation in long-term acute care hospital use after intensive care. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(3):339-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gage B, Morley M, Smith L, et al. . Post-Acute Care Payment Reform Demonstration: Final report. Volume 3 of 4 Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International ; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gage B, Morley M, Spain P, Ingber MJ. Examining Post Acute Care Relationships in an Integrated Hospital System. Waltham, MA: RTI International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makam AN, Nguyen OK, Zhou J, Ottenbacher KJ, Halm EA. Trends in long-term acute care hospital use in Texas from 2002-2011. Ann Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2015;2(3):1031. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gage B, Pilkauskas N, Dalton K, et al. . Long-term Care Hospital Payment System Monitoring and Evaluation. Phase II Report. Waltham, MA: RTI International; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chitnis AS, Edwards JR, Ricks PM, Sievert DM, Fridkin SK, Gould CV. Device-associated infection rates, device utilization, and antimicrobial resistance in long-term acute care hospitals reporting to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(10):993-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould CV, Rothenberg R, Steinberg JP. Antibiotic resistance in long-term acute care hospitals: the perfect storm. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27(9):920-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munoz-Price LS. Long-term acute care hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(3):438-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfenden LL, Anderson G, Veledar E, Srinivasan A. Catheter-associated bloodstream infections in 2 long-term acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(1):105-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn JM, Werner RM, David G, Ten Have TR, Benson NM, Asch DA. Effectiveness of long-term acute care hospitalization in elderly patients with chronic critical illness. Med Care. 2013;51(1):4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koenig L, Demiralp B, Saavoss J, Zhang Q. The Role of long-term acute care hospitals in treating the critically ill and medically complex: an analysis of nonventilator patients. Med Care. 2015;53(7):582-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Long Term Care Hospital Prospective Payment System. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Long-Term-Care-Hospital-PPS-Fact-Sheet-ICN006956.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Predictors of LTAC vs SNF Transfer

eTable 1. Data Sources and Definitions for Predictors Included in Full Model

eMethods 2. Sub-Cohorts for Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 2. Model Performance of Full Multilevel Models

eTable 3. Predictors of LTAC use from Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 4. Variation in LTAC use from Sensitivity Analyses

eReferences.