Abstract

Introduction

Palivizumab is indicated for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in high-risk children. Previous palivizumab utilization studies examined prior authorization claims but did not examine utilization within insured populations as a whole. This study describes outpatient palivizumab utilization trends and characterizes high-risk infants receiving palivizumab within Medicaid- and commercially insured populations.

Methods

Infants born July 1, 2003 through June 30, 2013 were identified in the MarketScan® Multistate Medicaid and Commercial claims databases. Infants with ≥ 18 months of continuous medical insurance enrollment with pharmacy benefits after birth and evidence of chronic lung disease of prematurity (CLDP), congenital heart disease (CHD), or preterm birth without CLDP or CHD were studied. Palivizumab use and demographic and clinical characteristics were measured in infant subgroups. Outpatient palivizumab utilization rates were calculated for each seasonal year (July–June) and for each infant subgroup.

Results

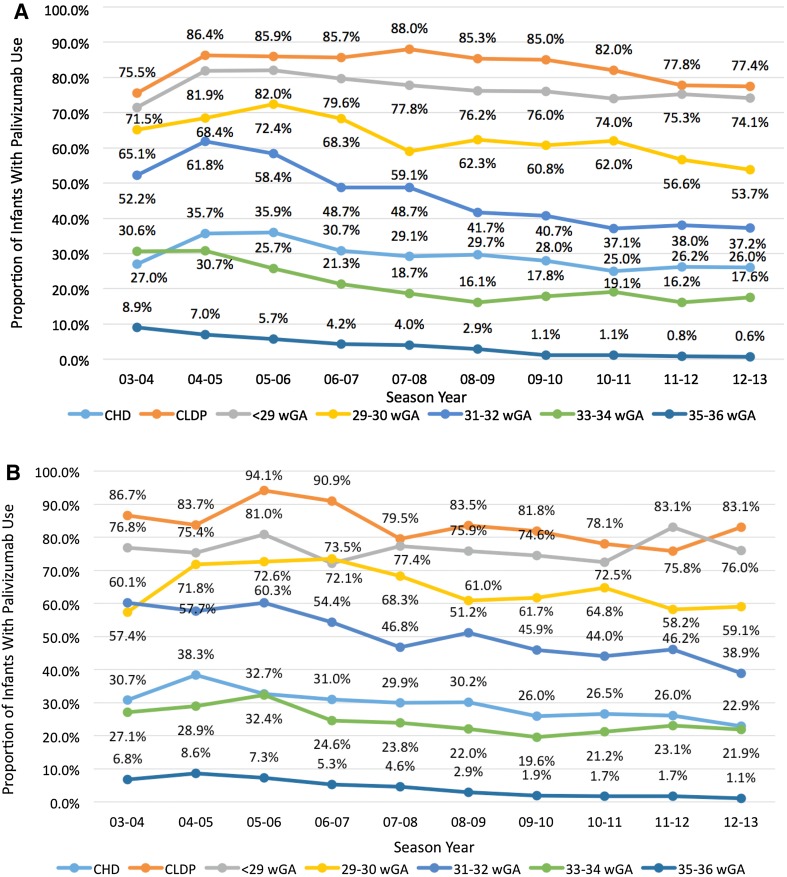

In total, 29,350 (2.1%) Medicaid-insured and 9589 (2.5%) commercially insured infants received palivizumab and had CLDP, CHD, or were born at < 37 weeks gestational age (wGA). Infants with CLDP (82%) and those < 29 wGA (78%) had the highest utilization. Decreases in utilization rates between the 2003–2004 and 2012–2013 seasons were seen among Medicaid-insured infants born at 29–36 wGA (all P < .0001), and commercially insured infants born at 31–32 wGA (P < .0001), 33–34 wGA (P = .055), 35–36 wGA (P < .0001), and with CHD (P = .003). Utilization by month was consistent across subgroups among Medicaid- and commercially insured infants, with most doses administered from November to March.

Conclusion

Palivizumab use is targeted to a small percentage of infants who are at highest risk of hospitalization for RSV disease. Utilization declined in recent years in both Medicaid- and commercially insured infant groups. Most palivizumab doses were administered from November to March, with most infants receiving ≤ 5 doses.

Funding

AstraZeneca.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40121-017-0178-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Infant, Palivizumab, Respiratory syncytial virus, Utilization

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most common cause of lower respiratory tract illness [1, 2], and is the leading cause of hospitalization in infants [3]. RSV infections primarily occur from late October to early April in the 10 regions defined by the US Department of Health and Human Services; [4] the exception is Florida, where the RSV season starts in July. Certain conditions in infants may increase the risk of severe RSV infection, including chronic lung disease of prematurity (CLDP)/bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease (CHD), and preterm birth [5, 6].

Prevention of disease is critical in managing RSV because there is no well-defined treatment standard, and interventions are essentially limited to supportive care [7]. Palivizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody, is indicated for the prevention of serious lower respiratory tract disease caused by RSV in high-risk children. Safety and efficacy have been established in randomized clinical studies of children with BPD or hemodynamically significant CHD and infants with a history of prematurity [i.e., infants born at ≤ 35 weeks gestational age (wGA)] [8, 9]. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval was granted in 1998 at a dose of 15 mg/kg administered intramuscularly every 28–30 days throughout the RSV season [10].

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) issues policy statements on the use of palivizumab for RSV immunoprophylaxis every 2–3 years; the policy statement was most recently updated in 2014 [11–14]. The 2009 and 2012 policies for RSV immunoprophylaxis recommended either 3 or 5 doses based on gestational age, chronologic age, and the presence of CLDP or hemodynamically significant CHD [12, 13]. In 2014, however, the AAP policy was revised to no longer recommend palivizumab prophylaxis for otherwise healthy infants born at 29–35 wGA or for those with hemodynamically significant CHD who were aged > 12 months [14]. The 2014 AAP guidance also defined CLDP as infants born at or before 32 wGA requiring > 21% oxygen supplementation for at least the first 28 days of life. Infants meeting this criterion were recommended to receive immunoprophylaxis up to 12 months of age. Infants between 12 and 23 months of age with CLDP were recommended for immunoprophylaxis only if they had received medical intervention (bronchodialators, steroids, diuretics, or oxygen) within 6 months prior to the onset of the RSV season [14].

Most previous palivizumab utilization studies identified patients through palivizumab referrals for prior authorization, and, therefore, do not offer insight into utilization within the entire population [15–17]. In addition, published studies have limited time horizons, with utilization described for only one RSV season or a few consecutive seasons. This study addresses an important data gap by describing trends in outpatient palivizumab utilization prior to the changes made in the 2014 AAP policy. Specifically, this study aims to describe outpatient palivizumab utilization trends over a 10-year period, while also attempting to better characterize the high-risk infant subpopulations who received palivizumab within Medicaid- and commercially insured populations.

Methods

Data Sources and Patient Identification

This analysis focused on infants selected from the Truven MarketScan® Multi-State Medicaid and Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters databases. These databases contain enrollment information, inpatient and outpatient medical claims data, and outpatient pharmacy claims for Medicaid enrollees from several geographically diverse states and enrollees from self-insured employers and health plans. The data were previously collected, statistically de-identified, and made compliant consistent with the privacy rule conditions set forth in Sects. 164.514 (a)–(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996; as such, approval from an institutional review board was not required. This noninterventional study is based on previously available data and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors; therefore, this study was not registered on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Infants born between July 1, 2003 and June 30, 2013 were identified in inpatient medical claims based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Infants must have been discharged alive from their birth hospitalization and continuously enrolled with pharmacy benefits for ≥ 18 months following birth.

DRGs, diagnosis, procedure, and medication codes were used to create mutually exclusive infant risk groups: infants with rare, complex medical conditions (cystic fibrosis; immunodeficiency; congenital anomalies of respiratory system; neuromuscular disease; other neuromuscular, immunologic, or genetic conditions; or organ transplants), CLDP, CHD, and preterm and full-term without the previously mentioned conditions (Supplementary Table 1). The subset of infants identified as having CLDP or CHD, or being born preterm with specific gestational age information (based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes), were included in the study consistent with FDA-approved product indication.

Study Variables

The primary outcome for this study was palivizumab utilization rates during the first 18 months of life. Utilization was calculated by seasonal year, defined as July 1–June 30. Palivizumab claims were identified in the outpatient setting by the presence of any of the following: outpatient prescription drug claim with a National Drug Code 54569549100, 54569549200, 60574411101, 60574411201, 60574411301, or 60574411401; and an outpatient medical claim for palivizumab administration (Current Procedural Terminology code: 90379; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes: S9562, C9003, J1565). Palivizumab drug and administration claims occurring within 7 days of each other were considered to represent the same dose. Although there is geographic and annual variability in the timing of RSV circulation in the United States, the RSV season was defined based on the national annual average as occurring between November 1 and March 31, based on data collected and published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [18]. The infant’s age relative to the start of RSV season (November 1) was also captured.

The number of palivizumab doses administered per infant was captured for the 2012–2013 seasonal year. As inpatient doses of palivizumab are not captured in the database, only outpatient utilization was assessed. The presence of at least one outpatient dose, the number of doses (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, or more doses), the month of dose, and timing of dose relative to the RSV season (defined below) were captured.

Sex and race/ethnicity (Medicaid-insured children only) were identified using enrollment records. The following birth-related characteristics were also measured: birth month, length of stay for birth hospitalization, and cost of birth hospitalization. In addition, proxies of health status at birth were determined from the birth hospitalization. Specifically, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) was identified by revenue codes, procedure codes, and inpatient claim diagnoses. Evidence of respiratory problems was based on the presence of ≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis of respiratory distress syndrome in newborn, apnea of newborn, and/or other respiratory problems (ICD-9-CM codes: 460–519) during the birth hospitalization.

Analyses

Data for Medicaid- and commercially insured infants were analyzed separately. Means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables; counts and proportions were reported for categorical variables. Utilization rates were calculated by seasonal year, and the average number of doses was calculated for the 2012–2013 season, the most recent season for which data were available. Palivizumab utilization was compared between the 2003–2004 and 2012–2013 seasons using Chi-squared tests.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Over 2.3 million Medicaid-insured infants and 2.1 million commercially insured infants born between July 1, 2003 and June 30, 2013 were identified for potential inclusion (Table 1). Of these, approximately 1.4 million (58%) Medicaid-insured infants and 576,000 (26%) commercially insured infants were discharged alive from their birth hospitalization while also having ≥ 18 months of continuous enrollment with pharmacy benefits. In addition, 36,437 (2.6%) Medicaid-insured and 14,198 (2.5%) commercially insured infants received palivizumab.

Table 1.

Patient selection

| Selection criterion | Total Medicaid-insured patients | Total commercially insured patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Insured infants born July 1, 2003 through June 30, 2013 | 2,381,611 | 100 | 2,180,385 | 100 |

| Discharged from birth hospitalization | 2,355,094 | 98.9 | 2,159,869 | 99.1 |

| 18 months of continuous enrollment and pharmacy data availability | 1,390,353 | 58.4 | 576,651 | 26.4 |

| Number of infants (%) | Palivizumab use (n = 36,437) | No palivizumab use (n = 1,353,916) | Palivizumab use (n = 14,198) | No palivizumab use (n = 562,453) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare complex medical conditionsa | 686 (1.9%) | 2231 (0.2%) | 305 (2.1%) | 799 (0.1%) |

| CLDP | 1416 (3.9%) | 299 (0.0%) | 586 (4.1%) | 125 (0.0%) |

| CHD | 5188 (14.2%) | 13,033 (1.0%) | 2525 (17.8%) | 6450 (1.1%) |

| PT | 22,746 (61.5%) | 93,128 (6.9%) | 6478 (45.6%) | 26,998 (4.8%) |

| < 29 wGA | 5835 (16.0%) | 1813 (0.1%) | 1223 (8.6%) | 382 (0.1%) |

| 29–30 wGA | 3998 (11.0%) | 2469 (0.2%) | 1039 (7.3%) | 581 (0.1%) |

| 31–32 wGA | 5458 (15.0%) | 6786 (0.5%) | 1651 (11.6%) | 1773 (0.3%) |

| 33–34 wGA | 5710 (15.7%) | 22,487 (1.7%) | 1991 (14.0%) | 6642 (1.2%) |

| 35–36 wGA | 1745 (4.8%) | 59,573 (4.4%) | 574 (4.0%) | 17,620 (3.1%) |

| PT, unknown GA | 4564 (12.5%) | 26,718 (2.0%) | 3647 (25.7%) | 19,049 (3.4%) |

| FT | 1299 (3.5%) | 968,743 (71.6%) | 458 (3.2%) | 408,981 (72.7%) |

| Unknown | 538 (1.5%) | 249,764 (18.4%) | 199 (1.4%) | 100,051 (17.4%) |

CHD congenital heart disease, CLDP chronic lung disease of prematurity, FT full-term, GA gestational age, PT preterm, wGA weeks gestational age

aIncludes cystic fibrosis; immunodeficiency; congenital anomalies of respiratory system; neuromuscular disease; other neuromuscular, immunologic, or genetic conditions; or organ transplants

The majority of palivizumab use (93.1% of Medicaid-insured and 93.2% of commercially insured infants) occurred among infants who were classified as < 37 wGA, preterm with unknown gestational age, CHD, or CLDP. Among infants who did not receive palivizumab, the majority (90% of Medicaid- and commercially insured infants) either could not be classified into a specific subgroup or were classified as full-term.

Demographic and Birth-Related Characteristics of Palivizumab Recipients

Demographic and birth-related characteristics, stratified by subgroup and palivizumab use, are presented in Tables 2 and 3. In the Medicaid-insured population, 33–42% of prophylaxed infants were born during the RSV season, 28–37% were aged < 3 months at the start of the RSV season, and 17–30% were aged 3–6 months at the start of the RSV season. For Medicaid-insured infants, the median length of stay of birth hospitalizations ranged from 8 to 72 days in infants who received palivizumab, and from 4 to 57 days in infants who did not receive palivizumab, with infants born < 29 wGA and infants with CLDP having the longest median length of stay. Most infants born at ≤ 34 wGA and infants with CLDP or CHD were admitted to the NICU and commonly had respiratory problems diagnosed at birth, with similar findings among those with and without palivizumab use. The median cost of a birth hospitalization in infants who received palivizumab ranged from US$9602 to US$130,278 across cohorts, with infants < 29 wGA and with CLDP having the highest median cost.

Table 2.

Demographic and birth-related characteristics among Medicaid-insured infants

| Birth-related characteristics | CLDP with Pali n = 1416 | CLDP w/o Pali n = 299 | CHD with Pali n = 5188 | CHD w/o Pali n = 13,033 | < 29 wGA with Pali n = 5835 | < 29 wGA w/o Pali n = 1813 |

29–30 wGA with Pali n = 3998 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Male | 860 (60.7) | 195 (65.2) | 2772 (53.4) | 6433 (49.4) | 2946 (50.5) | 922 (50.9) | 2087 (52.2) |

| Female | 556 (39.3) | 104 (34.8) | 2416 (46.6) | 6600 (50.6) | 2889 (49.5) | 891 (49.1) | 1911 (47.8) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 501 (35.4) | 119 (39.8) | 2117 (40.8) | 6083 (46.7) | 1660 (28.4) | 536 (29.6) | 1496 (37.4) |

| Black | 373 (26.3) | 95 (31.8) | 1286 (24.8) | 3835 (29.4) | 1785 (30.6) | 651 (35.9) | 1568 (39.2) |

| Hispanic | 81 (5.7) | 26 (8.7) | 406 (7.8) | 1440 (11.0) | 307 (5.3) | 153 (8.4) | 251 (6.3) |

| Other/unknown | 461 (32.6) | 59 (19.7) | 1379 (26.6) | 1675 (12.9) | 2083 (35.7) | 473 (26.1) | 683 (17.1) |

| Birth hospitalization | |||||||

| Length of stay in days, median (range) | 68 (1–239) | 47 (1–147) | 26 (1–331) | 4 (1–287) | 72 (1–320) | 57 (1–267) | 42 (1–239) |

| Total cost in US$, median range) | 130,278 (0–3,815,783) | 58,752 (0–1,213,094) | 53,780 (0–7,834,659) |

4135 (0–7,121,939) |

122,832 (0–3,793,546) | 68,422 (0–3,150,990) | 58,530 (0–1,487,620) |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 1394 (98.4) | 268 (89.6) | 4393 (84.7) | 5547 (42.6) | 5790 (99.2) | 1680 (92.7) | 3946 (98.7) |

| Presence of respiratory problems, n (%) | 1347 (95.1) | 255 (85.3) | 3602 (69.4) | 3819 (29.3) | 5501 (94.3) | 1443 (79.6) | 3554 (88.9) |

| Age relative to the first RSV season, n (%) | |||||||

| Born during the RSV season | 551 (38.9) | 171 (57.2) | 2008 (38.7) | 5609 (43.0) | 2262 (38.8) | 930 (51.3) | 1312 (32.8) |

| < 3 months at start of RSV season | 411 (29.0) | 44 (14.7) | 1565 (30.2) | 3027 (23.2) | 1630 (27.9) | 358 (19.7) | 1291 (32.3) |

| 3–6 months at start of RSV season | 347 (24.5) | 52 (17.4) | 1273 (24.5) | 3236 (24.8) | 1526 (26.2) | 360 (19.9) | 1184 (29.6) |

| Birth-related characteristics | 29–30 wGA w/o Pali n = 2469 | 31–32 wGA with Pali n = 5458 | 31–32 wGA w/o Pali n = 6786 | 33–34 wGA with Pali n = 5710 | 33–34 wGA w/o Pali n = 22,487 | 35–36 wGA with Pali n = 1745 | 35–36 wGA w/o Pali n = 59,573 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Male | 1291 (52.3) | 2851 (52.2) | 3529 (52.0) | 2913 (51.0) | 11,746 (52.2) | 886 (50.8) | 30,884 (51.8) |

| Female | 1178 (47.7) | 2607 (47.8) | 3257 (48.0) | 2797 (49.0) | 10,741 (47.8) | 859 (49.2) | 28,689 (48.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 824 (33.4) | 2308 (42.3) | 2588 (38.1) | 2754 (48.2) | 9379 (41.7) | 963 (55.2) | 27,661 (46.4) |

| Black | 1078 (43.7) | 2228 (40.8) | 3011 (44.4) | 2080 (36.4) | 9306 (41.4) | 504 (28.9) | 22,447 (37.7) |

| Hispanic | 186 (7.5) | 372 (6.8) | 581 (8.6) | 319 (5.6) | 1896 (8.4) | 95 (5.4) | 4742 (8.0) |

| Other/unknown | 381 (15.4) | 550 (10.1) | 606 (8.9) | 557 (9.8) | 1906 (8.5) | 183 (10.5) | 4723 (7.9) |

| Birth hospitalization | |||||||

| Length of stay in days, median (range) | 39 (1–254) | 27 (1–232) | 23 (1–213) | 14 (1–184) | 12 (1–230) | 8 (1–128) | 4 (1–248) |

| Total cost in US$, median range) | 47,280 (0–1,949,638) | 37,607 (0–1,484,627) | 26,162 (0–1,048,228) | 16,688 (0–988,644) | 11,630 (0–2,556,897) | 9602 (0–1,250,846) | 3363 (0–1,376,862) |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 2338 (94.7) | 5271 (96.6) | 6237 (91.9) | 5003 (87.6) | 17,441 (77.6) | 1114 (63.8) | 18,562 (31.2) |

| Presence of respiratory problems, n (%) | 2017 (81.7) | 4055 (74.3) | 4641 (68.4) | 3009 (52.7) | 9632 (42.8) | 700 (40.1) | 11,580 (19.4) |

| Age relative to the first RSV season, n (%) | |||||||

| Born during the RSV season | 1376 (55.7) | 2032 (37.2) | 3006 (44.3) | 2408 (42.2) | 9207 (40.9) | 593 (34.0) | 24,732 (41.5) |

| < 3 months at start of RSV season | 337 (13.6) | 1894 (34.7) | 1151 (17.0) | 2125 (37.2) | 4961 (22.1) | 648 (37.1) | 14,545 (24.4) |

| 3–6 months at start of RSV season | 460 (18.6) | 1279 (23.4) | 1885 (27.8) | 979 (17.1) | 6188 (27.5) | 426 (24.4) | 15,223 (25.6) |

CHD congenital heart disease, CLDP chronic lung disease of prematurity, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, Pali palivizumab, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, SD standard deviation, wGA weeks gestational age

Table 3.

Demographic and birth-related characteristics among commercially insured infants

| Birth-related characteristics | CLDP with Pali n = 586 |

CLDP w/o Pali n = 125 |

CHD with Pali n = 2525 |

CHD w/o Pali n = 6450 |

< 29 wGA with Pali n = 1223 |

< 29 wGA w/o Pali n = 382 |

29–30 wGA with Pali n = 1039 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Male | 368 (62.8) | 81 (64.8) | 1341 (53.1) | 3239 (50.2) | 645 (52.7) | 203 (53.1) | 555 (53.4) |

| Female | 218 (37.2) | 44 (35.2) | 1184 (46.9) | 3211 (49.8) | 578 (47.3) | 179 (46.9) | 484 (46.6) |

| Birth hospitalization | |||||||

| Length of stay in days, median (range) | 66 (1–209) | 43 (1–192) | 23 (1–300) | 4 (1–212) | 74 (1–336) | 58 (1–207) | 45 (1–318) |

| Total cost in US$, median (range) | 273,539 (0–4,352,342) | 179,513 (0–1,946,891) | 134,282 (0–7,064,240) | 7014 (0–2,549,157) | 283,178 (0–5,078,734) | 185,733 (0–1,931,297) | 145,576 (0–2,197,190) |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 565 (96.4) | 112 (89.6) | 2130 (84.4) | 2562 (39.7) | 1189 (97.2) | 322 (84.3) | 1009 (97.1) |

| Presence of respiratory problems, n (%) | 558 (95.2) | 112 (89.6) | 1741 (69.0) | 1843 (28.6) | 1136 (92.9) | 290 (75.9) | 936 (90.1) |

| Age relative to the first RSV season, n (%) | |||||||

| Born during the RSV season | 260 (44.4) | 61 (48.8) | 1042 (41.3) | 2722 (42.2) | 527 (43.1) | 187 (49.0) | 382 (36.8) |

| < 3 months at start of RSV season | 141 (24.1) | 22 (17.6) | 684 (27.1) | 1311 (20.3) | 294 (24.0) | 76 (19.9) | 292 (28.1) |

| 3–6 months at start of RSV season | 139 (23.7) | 30 (24.0) | 622 (24.6) | 1719 (26.7) | 296 (24.2) | 84 (22.0) | 287 (27.6) |

| Birth-related characteristics | 29–30 wGA w/o Pali n = 581 | 31–32 wGA with Pali n = 1651 | 31-32 wGA w/o Pali n = 1773 | 33–34 wGA with Pali n = 1991 | 33–34 wGA w/o Pali n = 6642 | 35–36 wGA with Pali n = 574 | 35–36 wGA w/o Pali n = 17,620 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Male | 328 (56.5) | 896 (54.3) | 949 (53.5) | 1061 (53.3) | 3701 (55.7) | 306 (53.3) | 9533 (54.1) |

| Female | 253 (43.5) | 755 (45.7) | 824 (46.5) | 930 (46.7) | 2941 (44.3) | 268 (46.7) | 8087 (45.9) |

| Birth hospitalization | |||||||

| Length of stay in days, median (range) | 42 (1–106) | 29 (1–122) | 25 (1–132) | 15 (1–130) | 13 (1–240) | 10 (1–141) | 4 (1–183) |

| Total cost in US$, median (range) | 132,856 (0–2,679,865) | 85,894 (0–2,179,730) | 67,693 (0–903,974) | 41,271 (0–633,084) | 33,037 (0–846,475) | 24,351 (0-713,298) | 6401 (0–1,126,573) |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 527 (90.7) | 1584 (95.9) | 1606 (90.6) | 1785 (89.7) | 5431 (81.8) | 438 (76.3) | 6840 (38.8) |

| Presence of respiratory problems, n (%) | 495 (85.2) | 1305 (79.0) | 1291 (72.8) | 1219 (61.2) | 3555 (53.5) | 312 (54.4) | 4635 (26.3) |

| Age relative to the first RSV season, n (%) | |||||||

| Born during the RSV season | 322 (55.4) | 674 (40.8) | 850 (47.9) | 877 (44.0) | 2794 (42.1) | 222 (38.7) | 7448 (42.3) |

| < 3 months at start of RSV season | 68 (11.7) | 490 (29.7) | 252 (14.2) | 690 (34.7) | 1132 (17.0) | 171 (29.8) | 3602 (20.4) |

| 3–6 months at start of RSV season | 98 (16.9) | 387 (23.4) | 409 (23.1) | 329 (16.5) | 1904 (28.7) | 157 (27.4) | 4795 (27.2) |

CHD congenital heart disease, CLDP chronic lung disease of prematurity, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, Pali palivizumab, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, SD standard deviation, wGA weeks gestational age

In the commercially insured population, 37–44% of infants were born during the RSV season, 24–35% of infants were aged < 3 months at the start of the RSV season, and 17–28% were aged 3–6 months at the start of the RSV season. The median length of stay of birth hospitalizations in commercially insured infants was 10–74 days in infants who received palivizumab and 4–58 days in infants who did not receive palivizumab, with infants born < 29 wGA and infants with CLDP having the longest median length of stay. The majority of commercially insured infants born at < 34 wGA and infants with CLDP or CHD were admitted to the NICU at birth, with respiratory problems being most commonly diagnosed, a finding also noted in the Medicaid population. The median cost of a birth hospitalization ranged from US$24,351 to US$283,178, with the highest cost observed in infants born at < 29 wGA and infants with CLDP.

Palivizumab Utilization

Average palivizumab utilization during the study period was highest among infants with CLDP and infants in the < 29 wGA group, followed by infants 29–30 wGA, infants 31–32 wGA, infants with CHD, infants 33–34 wGA, and infants 35–36 wGA (Fig. 1a, b). Among both the Medicaid- and commercially insured infant groups, utilization rates for those born < 29 wGA and those with CLDP remained consistent during the study period; there were no significant differences in utilization from the first seasonal year (2003–2004) to the last seasonal year (2012–2013) evaluated (< 29 wGA: Medicaid P = .251, commercial P = .890; CLDP: Medicaid P = .668, commercial P = .651).

Fig. 1.

a Palivizumab use during the study period among Medicaid-insured infants. There were significant differences in utilization from the 2003–2004 season to the 2012–2013 season in infants 29–30, 31–32, 33–34, and 35–36 wGA (P < .0001). b Palivizumab use during the study period among commercially insured infants. There were significant differences in utilization from the 2003–2004 season to the 2012–2013 season in infants 31–32 wGA (P < .0001), 35–36 wGA (P < .0001), and with CHD (P = .003). CHD congenital heart disease, CLDP chronic lung disease of prematurity, wGA weeks gestational age

In Medicaid-insured infants, utilization decreased significantly between the 2003–2004 and 2012–2013 seasons for infants 29–30, 31–32, 33–34, and 35–36 wGA (P < .001). In commercially insured infants, there was significant change in utilization from the first to last year evaluated among infants 31–32 wGA (P < .001) and 35–36 wGA (P < .001). Utilization in infants 33–34 wGA decreased over the study period and approached significance (P = .055); among infants 29–30 wGA, there was no significant change (P = .815). Utilization rates among infants classified as CHD decreased only in the commercially insured population (Medicaid: P = .502, commercial: P = .003) across the study period.

During the 2012–2013 RSV season, most doses of palivizumab were administered during the national average season of November to March (Medicaid: 89.1%, commercial: 89.5%; Fig. 2). The 2 months immediately adjacent to the defined RSV season (October and April) demonstrated the next highest utilization for both Medicaid- and commercially insured infants. Further analysis of the 2012–2013 season (Table 4) showed that most infants received < 5 doses, with an average range of 2.4–3.7 doses per infant. In both the Medicaid- and commercially insured populations, the average number of doses received was lowest for infants in the 33–34 wGA group and highest among commercially insured infants with CLDP.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of outpatient doses administered

Table 4.

Total number of outpatient doses received during the 2012–2013 RSV season

| CLDP | CHD | < 29 wGA | 29–30 wGA | 31–32 wGA | 33–34 wGA | 35–36 wGA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MED | COM | MED | COM | MED | COM | MED | COM | MED | COM | MED | COM | MED | COM | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (1.9) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.4 (1.7) | 3.2 (1.7) | 3.7 (1.8) | 3.2 (1.8) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.2 (1.7) | 3.2 (1.8) | 2.8 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.6) | 2.8 (1.7) |

| Number of doses | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 16.3 | 14.0 | 16.6 | 19.9 | 15.4 | 18.5 | 14.5 | 18.8 | 20.0 | 26.3 | 30.2 | 31.2 | 16.3 | 27.7 |

| 2 | 10.9 | 18.9 | 17.9 | 22.1 | 13.6 | 26.6 | 17.8 | 24.2 | 20.5 | 24.6 | 30.5 | 32.9 | 15.0 | 23.5 |

| 3 | 17.6 | 14.0 | 15.3 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 15.8 | 14.5 | 17.8 | 19.8 | 17.6 | 16.3 | 17.4 | 17.5 | 18.5 |

| 4 | 18.4 | 16.0 | 18.4 | 14.9 | 18.5 | 10.8 | 18.0 | 11.0 | 13.4 | 14.0 | 9.7 | 7.5 | 11.3 | 10.1 |

| 5 | 30.1 | 28.0 | 24.7 | 21.1 | 27.5 | 19.2 | 25.4 | 20.0 | 19.2 | 13.1 | 12.4 | 8.9 | 35.0 | 14.3 |

| 6 | 0.8 | 5.3 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 4.6 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.4 |

| 7+ | 5.9 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

CHD congenital heart disease, CLDP chronic lung disease of prematurity, COM commercially insured, MED Medicaid-insured, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, SD standard deviation, wGA weeks gestational age

Discussion

This analysis of two large US claims databases demonstrated that outpatient utilization of palivizumab occurred in < 3% of all infants born each year within both the Medicaid- and commercially insured populations. For both Medicaid- and commercially insured infants in this study, palivizumab utilization rates were highest among infants with CLDP and infants < 29 wGA and were consistent during the study period. These findings were anticipated, as these groups are considered to be at greatest risk of severe RSV disease and have consistently received the AAP’s recommendation to receive palivizumab. Of note, over the study period, palivizumab utilization decreased significantly among infants 29–36 wGA in the Medicaid-insured population and among certain infant cohorts (31–32 wGA, 35–36 wGA, and with CHD) in the commercially insured population. These decreases in utilization can be partially explained by changes to the 2009 and 2012 AAP policies on the use of palivizumab. These policy statements recommended that infants with CLDP, CHD, or born at < 32 wGA should receive 5 doses of palivizumab during the RSV season. In 2009 and 2012, infants born at 32–34 wGA were recommended to receive a maximum of 3 palivizumab doses, with cessation of therapy at 3 months of age. These data suggest that, within 1 year of a policy change, a decrease in utilization followed. In 2006, 2009, and 2012, the guidance continued to recommend RSV immunoprophylaxis for infants < 32 wGA; interestingly, however, utilization still decreased in this population [11–13]. The data suggest that the revisions to the guidance for 32–35 wGA infants unintentionally limited palivizumab use among infants < 32 wGA.

Despite the COID recommendations for RSV immunoprophylaxis in certain specified groups, palivizumab utilization was found to be inconsistent. In some cases, high-risk infants may not seem to “qualify” for immunoprophylaxis when considering confounding factors such as birth date and hospital discharge relative to the RSV season. Infants are at highest risk of severe RSV disease during the first 6 months of life [19]. As such, infants born shortly after one RSV season would be aged > 6 months during the following RSV season and may not have been identified to receive palivizumab. In a recent multicenter observational study by Anderson et al., it was found that 29–35 wGA infants had a high frequency of ICU admissions and invasive mechanical ventilation at younger chronologic ages [20]. In addition, the MarketScan® databases do not capture information on doses administered in the inpatient setting, and it is likely that some infants in both study populations received a palivizumab dose prior to hospital discharge, and that the overall utilization rates are somewhat higher than the outpatient-only rates.

Although it was not the intent of the study to compare within-cohort differences between infants who did or did not receive palivizumab, there were some consistent trends, including higher birth hospitalization length of stay and cost, rates of NICU admission, and diagnosis of respiratory problems among infant groups that received palivizumab. This suggests that, even within high-risk subgroups, prescribers may be recommending palivizumab for infants they perceive to be at greatest risk of severe RSV disease.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has assessed trends in palivizumab utilization over a 10-year period, and also the first to provide detailed information on the birth hospitalizations for palivizumab-treated infants. Although three previous studies provide context for our findings, none reported palivizumab utilization as a percentage of live births. As such, there is not an opportunity for benchmarking the overall utilization rate obtained in our study [15–17]. In the first of these studies, Diehl et al. [15] assessed compliance with the outpatient palivizumab dosing schedule as recommended by the 2006 AAP guidelines. These infants only received palivizumab if they met prior authorization (PA) criteria based on the COID recommendations. Of those patients who received palivizumab, only 30% of the prophylaxed infants were deemed to be compliant with the guidelines (i.e., they received their first outpatient dose prior to the start of the RSV season or within 37 days of discharge from their birth hospitalization, and they received subsequent monthly injections on time) [15]. Whereas the Diehl et al. [15] study gleaned insight into utilization during one season within a managed care organization, utilization was assessed by chronologic age rather than separately for infants in specific high-risk subgroups, which could explain why some infants may not have been compliant. It is conceivable that a correlation existed between gestational age and entire-season compliance (e.g., infants born > 32 wGA). Stewart et al. [17] evaluated outpatient palivizumab utilization and the relationship between noncompliance and RSV-related hospitalizations using the Optum Research database. Although each study described patients who received palivizumab, neither provided the total number of infants identified during the study period. Because of this, we cannot directly compare the utilization rates from these studies with the utilization rate observed in our study.

Buckley et al. [16] assessed palivizumab utilization rates using SelectHealth administrative claims data based on PA approval or denial from 2005 to 2008. Providers submitted palivizumab claims for 1090 infants over the 3 RSV seasons, among which 742 (68%) were approved, resulting in 648 (59%) receiving ≥ 1 dose of palivizumab. Infants who were PA-approved for palivizumab had a mean gestational age of 32.5 wGA, compared to 34.4 wGA in infants who were PA-denied palivizumab [16]. The average number of seasonal-year doses per approved infant was 3.59 during 2005–2006, 3.73 in 2006–2007, and 3.60 in 2007–2008. These are consistent with our observed number of seasonal-year doses administered. In our analysis of the 2012–2013 season, the average number of doses per infant by subgroup ranged from 2.4 to 3.7. However, Buckley et al. [16] only considered the rate of palivizumab recipients among those who applied for PA, rather than studying utilization among the entire population. In addition, there is no mention of whether inpatient palivizumab was included in the analysis.

Our data must be considered within the limitations of this study. Data used in this analysis were generated for reimbursement purposes, not for research; clinical coding is likely imperfect. We report outpatient palivizumab use only; therefore, presumably these data represent an underestimate of utilization, as some infants would be eligible to receive only 1 inpatient dose of palivizumab. Quantifying number of palivizumab doses administered proved to be challenging. First, our data were extracted from both administration in outpatient medical claims and drug procurement in outpatient pharmacy claims. In addition, because larger infants require multiple dosing vials to achieve the weight-based dosing guidelines for palivizumab, this can result in multiple pharmacy claims. In an effort to control for this, we created an algorithm to improve the accuracy of dose counting by combining administration and drug claims. Although this reduced the risk of overcounting doses, overestimation may still have occurred. Because of specificity limitations within ICD-9-CM codes, the current analysis considers all infants diagnosed with CHD rather than the narrower cohort of infants born with hemodynamically significant CHD. This may have caused our utilization rates to be lower in this population, as not all infants diagnosed with CHD are eligible to receive palivizumab. Furthermore, because this study was primarily a descriptive analysis of trends, we did not formally explore reasons for the observed differences in palivizumab utilization. Further research should be conducted to evaluate palivizumab utilization by geographic location and socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

This is the first study to assess trends in utilization of palivizumab over a 10-year period within the population of infants who were recommended by the AAP guidelines. Among infants born in the United States, palivizumab utilization from 2003 to 2013 was low relative to the total number of infants born each year, and specifically targeted to infants at high risk of hospitalization for severe RSV disease. Utilization has declined in recent years for both Medicaid- and commercially insured infants. In most cases, palivizumab immunoprophylaxis was appropriately utilized during the RSV season, with the majority of infants receiving ≤ 5 doses, as per current recommendations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study and the article processing charges was provided by AstraZeneca (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). All authors had full access to all data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. The authors thank Rebecca McCracken, MSPH, CMPP, of The Lockwood Group (Stamford, CT, USA) for providing editorial support, which was in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and funded by AstraZeneca. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Melissa Pavilack is an employee of AstraZeneca. Tara Gonzales is an employee of AstraZeneca. Kimmie K. McLaurin is an employee of AstraZeneca. Amanda M. Kong is an employee of Truven Health Analytics, an IBM Company, which was contracted by AstraZeneca for data analyses. Sally Wade is a consultant to Truven Health Analytics. Robert A. Clifford has been on the Speakers’ Bureau for MedImmune, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Sanofi-Pasteur.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously available data, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The data used for this analysis were from proprietary databases and could not be made publicly available due to agreements between Truven Health Analytics and the data contributors. More information about the data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/72DCF0605D43277C.

References

- 1.Shay DK, Holman RC, Newman RD, Liu LL, Stout JW, Anderson LJ. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations among US children, 1980-1996. JAMA. 1999;282:1440–1446. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stockman LJ, Curns AT, Anderson LJ, Fischer-Langley G. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalizations among infants and young children in the United States, 1997-2006. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:5–9. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822e68e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leader S, Kohlhase K. Respiratory syncytial virus-coded pediatric hospitalizations, 1997 to 1999. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:629–632. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV): symptoms and care. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/about/symptoms.html. Accessed 4 Mar 2016.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV): trends and surveillance. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/research/us-surveillance.html. Accessed 4 Mar 2016.

- 6.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVincenzo JP, McClure MW, Symons JA, Fathi H, Westland C, et al. Activity of oral ALS-008176 in a respiratory syncytial virus challenge study. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2048–2058. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feltes TF, Cabalka AK, Meissner HC, Piazza FM, Carlin DA, et al. Palivizumab prophylaxis reduces hospitalizations due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2003;143:532–540. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The IMpact-RSV Study Group Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:531–537. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Synagis (palivizumab) [prescribing information]. Gaithersburg, MD: MedImmune, LLC; 2014.

- 11.American Academy of Pediatrics. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, McMillan JA, eds. (2006) Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 560-567.

- 12.American Academy of Pediatrics. Respiratory syncytial virus. (2009) In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 560-569.

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics () Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, eds. (2012) Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 609-617.

- 14.Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines Committee Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014;134:415–420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diehl JL, Daw JR, Coley KC, Rayburg R. Medical utilization associated with palivizumab compliance in a commercial and managed Medicaid health plan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16:23–31. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckley BC, Roylance D, Mitchell MP, Patel SM, Cannon HE, Dunn JD. Description of the outcomes of prior authorization of palivizumab for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection in a managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16:15–22. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart DL, Ryan KJ, Seare JG, Pinsky B, Becker L, Frogel M. Association of RSV-related hospitalization and non-compliance with palivizumab among commercially insured infants: a retrospective claims analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:334. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haynes AK, Prill MM, Iwane MK, Gerber SI, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Respiratory syncytial virus—United States, July 2012-June 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1133–1336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalizations among children less than 24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e341–e348. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson EJ, Krilov LR, DeVincenzo JP, Checchia PA, Halasa N, et al. SENTINEL1: an observational study of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among US infants born at 29 to 35 weeks’ gestational age not receiving immunoprophylaxis. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:51–61. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this analysis were from proprietary databases and could not be made publicly available due to agreements between Truven Health Analytics and the data contributors. More information about the data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.