Abstract

Introduction

Physiologic changes during pregnancy may impact the pharmacokinetics of drugs. In addition, efficacy and safety/tolerability concerns have been identified for some antiretroviral agents.

Methods

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1–infected pregnant women (18–26 weeks gestation) receiving the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor rilpivirine 25 mg once daily were enrolled in this phase 3b, open-label study examining the impact of pregnancy on the pharmacokinetics of rilpivirine when it is given in combination with other antiretroviral agents. Blood samples (collected over the 24-h dosing interval) to assess total and unbound rilpivirine plasma concentrations were obtained during the second and third trimesters (24–28 and 34–38 weeks gestation, respectively) and 6–12 weeks postpartum. Pharmacokinetic parameters were derived using noncompartmental analysis and compared (pregnancy versus postpartum) using linear mixed effects modeling. Antiviral and immunologic response and safety were assessed.

Results

Nineteen women were enrolled; 15 had evaluable pharmacokinetic results. Total rilpivirine exposure was 29–31% lower during pregnancy versus postpartum; differences were less pronounced for unbound (pharmacodynamically active) rilpivirine. At study entry, 12/19 (63.2%) women were virologically suppressed; 10/12 (83.3%) women were suppressed at the postpartum visit. Twelve infants were born to the 12 women who completed the study (7 discontinued); no perinatal viral transmission was observed among 10 infants with available data. Rilpivirine was generally safe and well tolerated in women and infants exposed in utero.

Conclusion

Despite decreased rilpivirine exposure during pregnancy, treatment was effective in preventing mother-to-child transmission and suppressing HIV-1 RNA in pregnant women. Results suggest that rilpivirine 25 mg once daily, as part of individualized combination antiretroviral therapy, may be an appropriate option for HIV-1–infected pregnant women.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier, NCT00855335.

Keywords: HIV, Pharmacokinetics, Pregnancy, Rilpivirine

Introduction

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) is recommended for pregnant women with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infection to suppress virus replication and reduce the risk of perinatal virus transmission [1, 2]. Because women experience physiologic changes during pregnancy, it is important to assess the potential impact on the pharmacokinetic parameters of antiretroviral (ARV) agents [3]. Previous studies have demonstrated reduced exposure to protease inhibitors during pregnancy [4–6], while exposures to the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) nevirapine, efavirenz, etravirine, and rilpivirine have been reported to be reduced, largely similar, or even increased compared with postpartum [7–12].

Rilpivirine is approved for the treatment of HIV-1 infection, as part of cART, in treatment-naïve individuals and, in most countries, is restricted to those with HIV-1 RNA ≤ 100,000 copies/mL [13]. The efficacy and safety of rilpivirine in nonpregnant, treatment-naïve adults with HIV-1 infection have been demonstrated in 2 randomized, double-blinded, active-controlled, phase 3 studies (ECHO and THRIVE) [14, 15]. Other studies have demonstrated that virologically suppressed, HIV-1–infected subjects maintained virologic suppression after switching to a rilpivirine-containing complete regimen [either emtricitabine/rilpivirine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or emtricitabine/rilpivirine/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)] [16–18]. Current US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines [1] recommend the use of rilpivirine in combination with emtricitabine and TDF, or emtricitabine and TAF, in certain clinical situations in nonpregnant, treatment-naïve adults with pretreatment HIV-1 RNA < 100,000 copies/mL and a CD4+ count of > 200 cells/mm3.

Rilpivirine is currently recommended for the treatment of HIV-1–infected pregnant women in US Perinatal Guidelines (as an alternative agent), and guidelines from the European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) support its continued use during pregnancy [2, 19]. Animal studies have shown no evidence of teratogenicity with rilpivirine and, according to the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry, for rilpivirine, “sufficient numbers of first trimester exposures have been monitored to detect at least a twofold increase in risk of overall birth defects. No such increases have been detected to date” [20]. Clinical studies from the PANNA Network and IMPAACT P1026s have demonstrated reduced exposure to rilpivirine during pregnancy, but no perinatal transmission has been observed [11–13, 20].

In the present study, the pharmacokinetic parameters of several ARV agents, including rilpivirine, were evaluated during pregnancy and postpartum. Antiviral activity, safety/tolerability, and infant outcomes were also assessed. Results from the rilpivirine treatment arm are reported here; results from other treatment arms have been reported previously [5, 6, 9].

Methods

Study Design and Treatment

HIV-1–infected pregnant women at least 18 years of age were enrolled in this phase 3b, multicenter, open-label study to assess the influence of pregnancy on the pharmacokinetic parameters of ARV agents, including darunavir boosted by ritonavir [twice-daily (bid) and once-daily (qd) regimens] or cobicistat (qd), etravirine (bid), and rilpivirine (qd), as part of cART (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00855335).

Treatment in the rilpivirine arm included rilpivirine 25 mg qd, in combination with other ARVs, administered as either a combination of separate agents (EDURANT®; Janssen Therapeutics) or as part of the complete regimen rilpivirine/emtricitabine/TDF (COMPLERA®; Gilead Sciences) [13, 21]. Rilpivirine was dispensed to subjects under the supervision of the investigator, a qualified member of the investigational staff, or by a hospital/clinic pharmacist. Rilpivirine was taken with a meal. Eligible subjects were HIV-1–infected women in the second trimester of pregnancy (18–26 weeks gestation) and receiving rilpivirine 25 mg qd as part of their ARV regimen at the time of study entry. For women receiving rilpivirine as part of their first line of therapy (as a single agent in combination with other ARVs or as part of the complete regimen rilpivirine/emtricitabine/TDF), they must have had pretreatment HIV-1 RNA < 100,000 copies/mL, no evidence of specific NNRTI resistance-associated mutations (RAMs; K101E, K101P, E138A, E138G, E138K, E138R, E138Q, V179L, Y181C, Y181I, Y181V, H221Y, F227C, M230I or M230L, or the combination of K103N and L100I), and been using rilpivirine in combination with two active nucleos(t)ides. For women receiving rilpivirine as part of the complete regimen rilpivirine/emtricitabine/TDF and treatment-experienced (i.e., switched from another ARV regimen), they must have had no history of virologic failure, been virologically suppressed for ≥ 6 months prior to switching to rilpivirine/emtricitabine/TDF, been on their first or second ARV regimen prior to switching to rilpivirine/emtricitabine/TDF, and have no current or past history of resistance to rilpivirine, emtricitabine, or TDF. Additional eligibility criteria included a normal obstetrical exam within 2 weeks of the screening visit, a normal fetal ultrasound, receiving care for pregnancy and HIV management from an obstetrician and/or primary HIV healthcare provider and agreed to continue doing so for the duration of the study, willing to remain on rilpivirine and a background regimen for the duration of the study (including 12 weeks postpartum), and able to comply with the protocol requirements.

Exclusion criteria included active acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)–defining illness (except stable, cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma or wasting syndrome caused by HIV infection); presence of newly diagnosed HIV-related opportunistic infection or any medical condition requiring acute therapy; use of certain concomitant medications; use of disallowed medication per the current prescribing information (as appropriate) for rilpivirine and the ARV background regimen; use of an investigational agent within 90 days prior to screening; any current obstetrical complication; any known fetal anomaly; uncontrolled diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2, or gestational diabetes; untreated hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism; certain hepatic abnormalities; certain laboratory abnormalities; neurological condition requiring medication; current alcohol or recreational drug use; and any condition that could compromise the subject’s safety or adherence to the protocol.

Adherence to study medications was assessed based on 4-day recall, pill counts, maintenance of adequate medication dispensing, and return records of all medications provided.

The primary objective of this analysis was to compare rilpivirine pharmacokinetic parameters during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy to those postpartum. Secondary objectives were to evaluate antiviral activity, safety, and tolerability of rilpivirine-based ARV regimens during pregnancy and postpartum; to compare rilpivirine concentrations between plasma and cord blood samples at the time of delivery; and to assess outcomes for infants of women treated with rilpivirine during pregnancy.

All subjects provided written informed consent to participate in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, and its later amendments, and is consistent with Good Clinical Practices and applicable regulatory requirements. The study protocol and amendments were reviewed by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board.

Pharmacokinetic Evaluations

Blood samples were collected over the 24-h dosing interval to assess the plasma pharmacokinetics of total and unbound rilpivirine. Pharmacokinetic evaluations occurred at clinic visits during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy (24–28 and 34–38 weeks gestation, respectively) and 6–12 weeks postpartum; during these visits, study staff observed subjects’ intake of rilpivirine. Matching cord blood and maternal plasma samples were taken at the intrapartum visit (when feasible). Plasma concentrations of rilpivirine were determined using a validated, specific, and sensitive liquid chromatography mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) method. The fraction of unbound rilpivirine was determined via separation through dialysis of pooled (per subject and per pharmacokinetic visit) plasma samples and LC–MS/MS of the fractions. Pharmacokinetic parameters were derived using noncompartmental analysis (model 200, extravascular input, plasma data; Phoenix™ WinNonlin®, v.6.2.1; Tripos LP, St. Louis, MO, USA) and included area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time of administration to 24 h postdose (AUC24h), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), minimum plasma concentration (Cmin), observed plasma concentration prior to the beginning of a dosing interval (C0h), and time to reach the maximum plasma concentration (tmax).

Antiviral Activity and Safety/Tolerability

Antiviral response (defined as HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL), immunologic response, and safety/tolerability were evaluated at each study visit, beginning with the baseline visit at 18–26 weeks gestation. Immunologic response was reported as CD4+ percentage, in lieu of absolute CD4+ count, because CD4+ percentage has been reported to be more stable in HIV-1–negative women during pregnancy compared with the 12-week postdelivery period [22]. Laboratory parameters included albumin and α1-acid glycoprotein; concentrations of these plasma proteins are typically reduced during pregnancy due to hemodilution [23] and rilpivirine is highly bound to plasma proteins [13].

Statistical Analyses

Rilpivirine pharmacokinetic parameters (total and unbound) were summarized per exposure period [second and third trimesters (tests) and postpartum (reference)] and compared between pregnancy and postpartum using linear mixed effects modeling. Efficacy and safety data were summarized using descriptive statistics; no comparisons across exposure periods were performed.

Results

Subject Disposition

A total of 19 women were enrolled in the rilpivirine arm of the study and all received rilpivirine 25 mg qd (intent-to-treat population). Fifteen of the 19 women (79%) had ≥ 1 pharmacokinetic sample taken, and were thus included in the pharmacokinetic population. Evaluable pharmacokinetic results were available for 15, 13, and 11 women for the second trimester, third trimester, and postpartum visits, respectively. Twelve of the 19 women (63%) completed the study; reasons for discontinuation of the remaining 7 women included: pregnancy terminated (n = 1), did not fulfill all inclusion/exclusion criteria [n = 2 (due to exclusionary laboratory result and preexisting rilpivirine RAMs)], lost to follow-up (n = 1), noncompliant (n = 1), withdrew consent (n = 1), and other [n = 1 (woman had suspected virologic failure, but was suppressed at the withdrawal visit)]. All 12 women who completed the study gave birth to 1 infant each; HIV-1 infection data were available for 10 of these infants.

Subject Population

The median (range) age of the women at screening was 26 (21–36) years, 17 (90%) women were black or African American, 12 (63%) had HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL, the median (range) HIV-1 RNA level was 1.69 (1.3–3.4) log10 copies/mL, the median (range) CD4+ count was 427.0 (16–1296) cells/mm3, and the median (range) time since conception was 158 (137–190) days (Table 1). Per the inclusion criteria, all women were taking rilpivirine 25 mg qd at baseline; 3 (16%) women used rilpivirine as a single agent in combination with other ARVs and 16 (84%) women used the complete regimen rilpivirine/emtricitabine/TDF. Among the 16 women who used the complete regimen, 3 (19%) were treatment-experienced and virologically suppressed (without previous virologic failure) when they switched to rilpivirine/emtricitabine/TDF, and 13 (81%) used the complete regimen as their first line of therapy. Among all women, background regimens included emtricitabine and TDF [n = 10 (53%)]; emtricitabine, TDF, and zidovudine [n = 8 (42%)]; and lamivudine and zidovudine [n = 1 (5%)]. All 9 (47%) women who were using zidovudine were enrolled at a single study site and started cART with oral zidovudine as a standard-of-care practice (i.e., zidovudine was not added to the regimen due to suspected virologic failure). The mean (standard error) duration of rilpivirine intake in the study was 17.7 (2.1) weeks [11.8 (1.2) weeks prebirth and 9.2 (0.5) weeks postbirth]. The mean (standard error) percentage of rilpivirine doses reported to be taken in the 4 days preceding a visit ranged from 95% (5.0) to 100% throughout the study.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | n = 19 |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age at screening, median (range) (years) | 26 (21–36) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 1 (5) |

| Black or African American | 17 (90) |

| Hispanic | 1 (5) |

| BMI, median (range) (kg/m2) | 31 (22–56) |

| First pregnancy, n (%) | |

| No | 12 (63) |

| Yes | 7 (37) |

| Time since conception, median (range) (days) | 158 (137–190) |

| Disease characteristics | |

| Known duration of HIV infection, median (range) (years) | 0.5 (0.2–12.8) |

| HIV-1 RNA at baseline (copies/mL), n (%) | |

| < 50 | 12 (63) |

| 50 to < 400 | 4 (21) |

| 400 to < 1000 | 1 (5) |

| ≥ 1000 | 2 (11) |

| CD4+ count at baseline (cells/mm3), n (%) | |

| < 50 | 1 (5) |

| 50 to < 100 | 0 |

| 100 to < 200 | 2 (11) |

| 200 to < 350 | 5 (26) |

| ≥ 350 | 11 (58) |

| Combination ARVs used with rilpivirine at baseline, n (%)a | |

| Emtricitabine + TDF | 10 (53) |

| Emtricitabine + TDF + zidovudine | 8 (42) |

| Lamivudine + zidovudine | 1 (5) |

BMI body mass index, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, ARV antiretroviral, TDF tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

aSixteen women used the complete regimen rilpivirine/emtricitabine/TDF and 3 women used rilpivirine as a single agent in combination with other ARVs

Pharmacokinetics

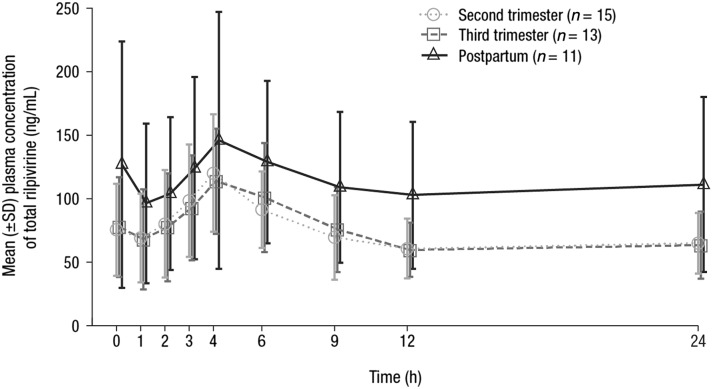

Total rilpivirine plasma concentrations over the entire 24-h dosing interval were lower during pregnancy than postpartum, and comparable between the second and third trimesters of pregnancy (Fig. 1). Correspondingly, mean values for total rilpivirine C0h, Cmin, Cmax, and AUC24h were similar during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, and these values were lower than those during the postpartum period (Table 2). Compared with postpartum, total rilpivirine AUC24h was 29% and 31% lower during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively, and Cmax was 21% and 20% lower during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively. The decrease in unbound rilpivirine exposure during pregnancy was less pronounced than for total rilpivirine. Compared with postpartum, unbound rilpivirine AUC24h was 25% and 22% lower during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively, and Cmax was 15% and 10% lower during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively. Median tmax was 4.00 h at all 3 time points during pregnancy and postpartum.

Fig. 1.

Mean (±SD) plasma concentration–time profiles of total rilpivirine during pregnancy and postpartum over the 24-h dosing interval. SD standard deviation

Table 2.

Mean (±SD) pharmacokinetic parameters and within-subject comparisons for total and unbound rilpivirine during pregnancy and postpartum

| Parameter | Second trimester | Third trimester | Postpartum | LS mean ratio (90% CI) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second trimester versus postpartum | Third trimester versus postpartum | ||||

| Total rilpivirine | |||||

| n | 15 | 13 | 11 | 15 versus 11 | 13 versus 11 |

| C0h (ng/mL) | 75.6 ± 36.2 | 78.0 ± 39.1 | 127 ± 97.0 | ND | ND |

| Cmin (ng/mL) | 54.3 ± 25.8 | 52.9 ± 24.4 | 84.0 ± 58.8 | 64.82 (51.62–81.39)a | 57.61 (45.81–72.45)a |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 121 ± 45.9 | 123 ± 47.5 | 167 ± 101 | 79.47 (63.21–99.91) | 79.99 (63.36–100.99) |

| tmax (h)b | 4.00 (1.00–9.00) | 4.00 (2.00–24.93) | 4.00 (2.03–25.08) | ND | ND |

| AUC24h (ng·h/mL) | 1792 ± 711 | 1762 ± 662 | 2714 ± 1535 | 70.83 (55.23–90.83) | 69.27 (53.80–89.18) |

| Unbound rilpivirine | |||||

| n | 15 | 13 | 11 | 15 versus 11 | 13 versus 11 |

| Cmin (ng/mL) | 0.144 ± 0.0676 | 0.148 ± 0.0706 | 0.196 ± 0.115 | 68.41 (54.81–85.38)c | 63.59 (50.87–79.49)c |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 0.317 ± 0.111 | 0.342 ± 0.135 | 0.387 ± 0.172 | 84.69 (66.91–107.20) | 89.63 (70.43–114.06) |

| AUC24h (ng·h/mL) | 4.74 ± 1.83 | 4.94 ± 1.95 | 6.35 ± 2.79 | 74.71 (56.64–98.56) | 77.85 (58.65–103.34) |

SD standard deviation, LS least squares, CI confidence interval, C0h observed plasma concentration prior to the beginning of a dosing interval, ND not determined, Cmin minimum plasma concentration, Cmax maximum plasma concentration, tmax time to reach the maximum plasma concentration, AUC24h area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time of administration to 24 h postdose, BLQ below the limit of quantification, LLOQ lower limit of quantification

aBLQ values were excluded for Cmin; second trimester, n = 14; third trimester, n = 13; and postpartum, n = 10. Statistical analyses were also performed including the BLQ values (included as 0.5 × LLOQ); the LS mean ratio (90% CI) for the second trimester versus postpartum was then 75.50 (31.35–181.80), and for the third trimester versus postpartum was 95.81 (38.46–238.64)

bData are presented as median (range)

cBLQ values were excluded for Cmin; second trimester, n = 14; third trimester, n = 13; and postpartum, n = 10. Statistical analyses were also performed including the BLQ values (included as 0.5 × LLOQ); the LS mean ratio (90% CI) for the second trimester versus postpartum was then 82.70 (33.76–202.61), and for the third trimester versus postpartum was 111.74 (43.97–283.93)

For Cmin, the statistical comparisons of total and unbound rilpivirine values during pregnancy versus postpartum were carried out both without and with 2 values that were below the limit of quantification (BLQ), which is indicative of nonadherence; 1 woman had a Cmin value BLQ at the second trimester visit (reported adherence was 75% in the 4 days prior to the visit) and 1 woman had a Cmin value BLQ at the postpartum visit (reported adherence was 100% in the 4 days prior to the visit). Excluding the Cmin values that were BLQ, compared with postpartum, total rilpivirine Cmin was 35% and 42% lower during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively; unbound Cmin was 32% and 36% lower during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively (Table 2). Including the Cmin values that were BLQ, compared with postpartum, the 90% confidence intervals around the least squares mean ratios were very wide; total rilpivirine Cmin was 24% and 4% lower during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively, and unbound Cmin was 17% lower and 12% higher during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively.

Individual cord/maternal plasma ratios of total rilpivirine on the day of delivery were analyzed in 8 women; the median ratio was 0.55 (range: 0.43-0.98).

Efficacy

Among the 10 infants with available data, no perinatal viral transmission was observed.

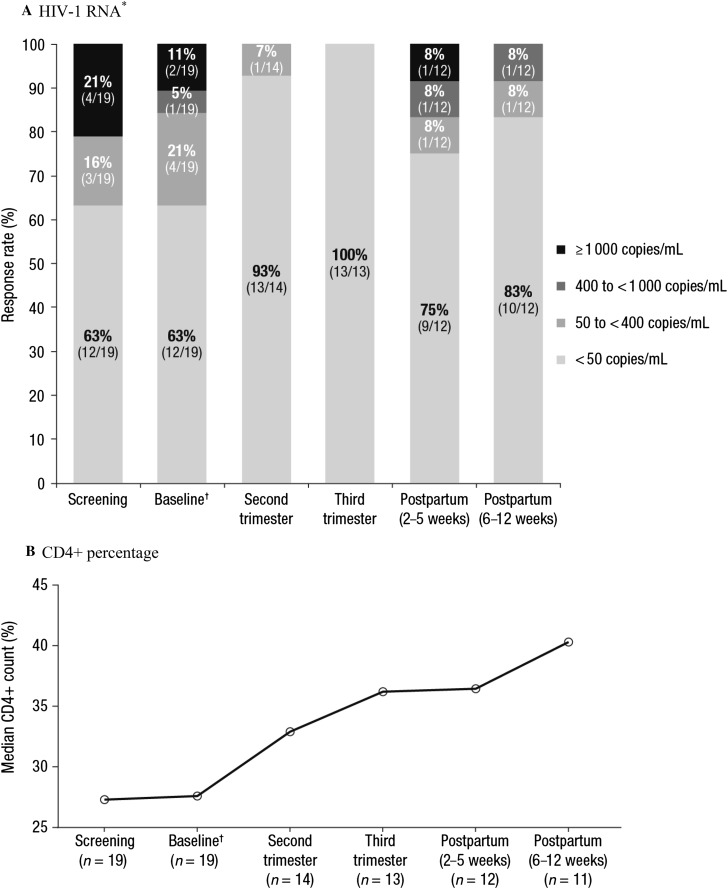

At baseline, 12 of 19 (63%) women were virologically suppressed. Viral suppression was reached or maintained during the study in 13 of 14 (93%) women with available data at the second trimester visit, 13 of 13 (100%) at the third trimester visit, and 10 of 12 (83%) at the end-of-study visit (6–12 weeks postpartum visit; Fig. 2a). Though the sample size was small, the addition of zidovudine to the background regimen did not appear to have an impact on virologic suppression data; of the 10 women who were suppressed at study completion, 3 used zidovudine in their background regimen and 7 did not use zidovudine. For the 2 women who were not suppressed at the end of study visit, both used a background regimen of emtricitabine, TDF, and zidovudine. One of these women was suppressed at baseline and all visits during pregnancy, but had an HIV-1 RNA level of 9640 copies/mL at the 2–5 weeks postpartum visit and an HIV-1 RNA level of 50 copies/mL at the 6–12 weeks postpartum visit; this woman did not meet the criteria for virologic failure. The other woman who was not suppressed at the end of study visit had virologic failure postpartum (i.e., 2 consecutive HIV-1 RNA measurements of > 200 copies/mL after reaching HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL) and suspected nonadherence postpartum (at the 6–12 weeks postpartum visit, the rilpivirine predose concentration was BLQ, while it was 155 and 131 ng/mL at the second and third trimester visits, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Antiviral activity over time, as assessed by a HIV-1 RNA* and b CD4+ percentage during pregnancy and postpartum. HIV-1 human immunodeficiency virus-1, qd once daily, ARV antiretroviral. *For each time point, percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. †The baseline visit occurred at 18–26 weeks gestation; per the inclusion criteria, eligible subjects were receiving rilpivirine 25 mg qd as part of their ARV regimen at the time of study entry

As noted previously, 1 woman withdrew from the study due to suspected virologic failure (background regimen: emtricitabine and TDF). Virologic failure was suspected due to HIV-1 RNA levels that did not decrease by ≥ 0.5 log 4 weeks after baseline. Moreover, the rilpivirine predose concentration at the second trimester visit was BLQ, and thus indicative of nonadherence. This woman was subsequently suppressed at the time of withdrawal with an HIV-1 RNA level of 36 copies/mL. For the 2 women with (suspected) virologic failure, no resistance test results were available at the time of failure.

Median CD4+ percentage, which is reported in lieu of absolute CD4+ count (see “Methods”), increased over time (Fig. 2b).

Safety/Tolerability

Nine of 19 women (47%) experienced ≥ 1 adverse event (AE); none of the AEs were considered by the investigator to be at least possibly related to the study medication and none led to study discontinuation (Table 3). The most common AEs (occurring in > 1 woman) were chorioamnionitis [n = 3 (16%)] and vaginal discharge [n = 2 (11%)]. There was 1 case of premature labor (delivery at 34 weeks gestation). In total, 4 women experienced ≥ 1 serious AE (SAE). The SAEs included blurred vision, sepsis, chorioamnionitis, intrauterine death, preeclampsia, and premature labor [each in 1 subject except chorioamnionitis (n = 2)]; none were considered by the investigator to be at least possibly related to the study medication. One woman experienced chorioamnionitis associated with sepsis and intrauterine death of the fetus (all grade 3 in severity); this woman was withdrawn from the study due to terminated pregnancy.

Table 3.

Summary of AEs

| Incidence, n (%) | n = 19 |

|---|---|

| Any AE | 9 (47) |

| Any AE considered at least possibly related to study medication | 0 |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation | 0 |

| Any SAE | 4 (21) |

| Any grade 3 or 4 AE | 1 (5) |

| Most common AEs (occurring in > 1 woman) | |

| Chorioamnionitis | 3 (16) |

| Vaginal discharge | 2 (11) |

AE adverse event, SAE serious adverse event

Serum albumin and α1-acid glycoprotein concentrations were evaluated in 19 women at baseline, 15 at the second trimester visit, 13 at the third trimester visit, and 12 at the 6–12 weeks postpartum visit. Mean albumin concentrations were 32.8 g/L (baseline), 31.6 g/L (second trimester), 29.6 g/L (third trimester), and 39.0 g/L (6–12 weeks postpartum). Mean α1-acid glycoprotein concentrations were 605.8 mg/L (baseline), 600.0 mg/L (second trimester), 603.1 mg/L (third trimester), and 955.0 mg/L (6–12 weeks postpartum).

Seven of the 12 infants (58%) born to women who completed the study experienced ≥ 1 AE, all of which were grade 1 or 2 in severity; none of the AEs were considered by the investigator to be related to study medication or HIV infection. The most common AEs (occurring in > 1 infant) were exomphalos [n = 2 (17%)] and neonatal vomiting [n = 2 (17%)]. Six (50%) infants experienced ≥ 1 SAE. These SAEs included talipes, ventricular septal defect, neonatal vomiting, neonatal fever, neonatal sepsis, medical observation, premature baby, and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome; each was reported in a single infant, except neonatal vomiting [n = 2 (17%)], and none were considered by the investigator to be related to HIV infection.

Discussion

Findings from the present study examining ARV pharmacokinetics in HIV-1–infected women demonstrated that exposure to rilpivirine is reduced during pregnancy compared with postpartum. Rilpivirine exposure was similar during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Compared with total rilpivirine, the reduction in exposure during pregnancy was less pronounced for unbound (pharmacodynamically active) rilpivirine. Despite the decrease during pregnancy, total rilpivirine AUC24h during each of the 3 time points (second and third trimesters of pregnancy and postpartum) was in the range of those observed in nonpregnant adults administered rilpivirine 25 mg qd (mean ± standard deviation 2235 ± 851 ng·h/mL) [13]. Similar decreases in total rilpivirine exposure during pregnancy have also been observed previously, including one study in which rilpivirine exposure (AUC) was 23% lower during the second trimester of pregnancy compared with postpartum and 20% lower during the third trimester of pregnancy compared with postpartum [11, 12]. Apart from general physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy, these decreases in rilpivirine exposure during pregnancy are likely, at least partly, related to the metabolism of rilpivirine by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP34A, as the activity of this enzyme is increased during pregnancy [1, 3, 13].

The earlier evaluations of rilpivirine pharmacokinetics during pregnancy focused only on total rilpivirine [11, 12]. In the current study, which included assessment of unbound (pharmacodynamically active) rilpivirine, the decreases in exposure seen during pregnancy were less pronounced for unbound rilpivirine compared with total rilpivirine, although the differences were limited. Rilpivirine is approximately 99.7% bound to plasma proteins, primarily albumin [13]; however, changes in plasma protein content during pregnancy only had a limited impact on the fraction of unbound rilpivirine.

Rilpivirine had a favorable safety/tolerability profile in pregnant women; none of the maternal AEs were considered by the investigator to be at least possibly related to study medication and there were no discontinuations due to an AE. Importantly, despite decreased rilpivirine exposure during pregnancy, treatment was effective in suppressing HIV-1 infection in pregnant women and preventing mother-to-child transmission. No perinatal virus transmission was observed for any of the 10 infants with available data, consistent with previous studies [11, 12]. Individual cord/maternal plasma ratios of total rilpivirine on the day of delivery were also in the range of previous observations [median (range) 0.55 (0.3–0.8)] [12]. Moreover, rilpivirine was generally safe and well tolerated in infants; all infant AEs were mild in severity and none were considered by the investigator to be related to study medication or HIV infection. These results are similar to those of previous clinical studies assessing rilpivirine exposure in pregnant women.

This study was limited in some ways. The population size was small and data collection began after the first trimester of pregnancy. In addition, study medication administration was only observed on days in which women visited the clinic, and thus adherence during the study may have been incomplete for some women.

Conclusion

In summary, these study findings demonstrated that rilpivirine exposure was lower during pregnancy compared with postpartum, and the decrease was less pronounced for unbound rilpivirine compared with total rilpivirine. Despite this decrease in exposure, treatment with rilpivirine 25 mg qd was effective in preventing mother-to-child virus transmission and in suppressing HIV-1 RNA in pregnant women in this study. Rilpivirine was generally safe and well tolerated in both women and their infants during pregnancy. Similar findings have been reported in other studies with rilpivirine in pregnant women [11, 12]. Together, these results suggest that rilpivirine 25 mg qd, as part of individualized cART, may be an appropriate option for HIV-1–infected pregnant women with close virologic monitoring.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families, and the study investigators.

Funding

Funding for this study and the article processing charges were provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs. All authors had full access to the study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Courtney St. Amour, PhD, of MedErgy, and was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs.

Authorship

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Prior Presentation

These data were previously presented, in part, in abstract and poster form at the 7th International Workshop on HIV & Women, February 11–12, 2017, Seattle, WA, USA.

Disclosures

Olayemi Osiyemi has participated in speaker programs for Janssen, AbbVie, and Gilead; served on advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, AbbVie, Janssen, and Durata; and received research grants from Forest Laboratories and Gilead. Salih Yasin has no financial interests to disclose. Carmen Zorrilla has received grant/research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, Merck, and Tibotec. Ceyhun Bicer is a consultant for Janssen and an employee of BICER Consulting & Research (Antwerp, Belgium). Vera Hillewaert is a full-time employee of Janssen. Kimberley Brown is a full-time employee of Janssen. Herta M. Crauwels is a full-time employee of Janssen.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All subjects provided written informed consent to participate in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, and its later amendments, and is consistent with Good Clinical Practices and applicable regulatory requirements. The study protocol and amendments were reviewed by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry Advisory Committee Consensus Statement

In reviewing all reported defects from the prospective registry, informed by clinical studies and retrospective reports of antiretroviral exposure, the Registry finds no apparent increases in frequency of specific defects with first trimester exposures and no pattern to suggest a common cause. While the Registry population exposed and monitored to date is not sufficient to detect an increase in the risk of relatively rare defects, these findings should provide some assurance when counseling patients. However, potential limitations of registries such as this should be recognized. The Registry is ongoing. Given the emergence of new therapies about which data are still insufficient, health care providers are strongly encouraged to report eligible patients to the Registry at http://www.APRegistry.com.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/DD1DF06034FBB700.

References

- 1.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed 17 Oct 2017.

- 2.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant women with HIV infection and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/PerinatalGL.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2017.

- 3.Anderson GD. Pregnancy-induced changes in pharmacokinetics: a mechanistic-based approach. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(10):989–1008. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert EM, Darin KM, Scarsi KK, et al. Antiretroviral pharmacokinetics in pregnant women. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(9):838–855. doi: 10.1002/phar.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zorrilla CD, Wright R, Osiyemi OO, et al. Total and unbound darunavir pharmacokinetics in pregnant women infected with HIV-1: results of a study of darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg administered twice daily. HIV Med. 2014;15(1):50–56. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crauwels HM, Kakuda TN, Ryan B, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once-daily darunavir/ritonavir in HIV-1-infected pregnant women. HIV Med. 2016;17(9):643–652. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamorde M, Byakika-Kibwika P, Okaba-Kayom V, et al. Suboptimal nevirapine steady-state pharmacokinetics during intrapartum compared with postpartum in HIV-1-seropositive Ugandan women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(3):345–350. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9871b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cressey TR, Stek A, Capparelli E, et al. Efavirenz pharmacokinetics during the third trimester of pregnancy and postpartum. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):245–252. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823ff052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramgopal M, Osiyemi O, Zorrilla C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of total and unbound etravirine in HIV-1-infected pregnant women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(3):268–274. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulligan N, Schalkwijk S, Best BM, et al. Etravirine pharmacokinetics in HIV-infected pregnant women. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:239. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schalkwijk S, Colbers A, Konopnicki D, et al. Lowered rilpivirine exposure during the third trimester of pregnancy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected women. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(8):1335–1341. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran AH, Best BM, Stek A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of rilpivirine in HIV-infected pregnant women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(3):289–296. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.EDURANT® (rilpivirine) [package insert]. Titusville: Janssen Therapeutics; 2015.

- 14.Cohen CJ, Molina JM, Cahn P, et al. Efficacy and safety of rilpivirine (TMC278) versus efavirenz at 48 weeks in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients: pooled results from the phase 3 double-blind randomized ECHO and THRIVE Trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(1):33–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824d006e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson MR, Elion RA, Cohen CJ, et al. Rilpivirine versus efavirenz in HIV-1-infected subjects receiving emtricitabine/tenofovir DF: pooled 96-week data from ECHO and THRIVE studies. HIV Clin Trials. 2013;14(3):81–91. doi: 10.1310/hct1403-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palella FJ, Jr, Fisher M, Tebas P, et al. Simplification to rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate from ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor antiretroviral therapy in a randomized trial of HIV-1 RNA-suppressed participants. AIDS. 2014;28(3):335–344. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orkin C, DeJesus E, Ramgopal M, et al. Switching from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate to tenofovir alafenamide coformulated with rilpivirine and emtricitabine in virally suppressed adults with HIV-1 infection: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3b, non-interfority study. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(5):e195–e204. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeJesus E, Ramgopal M, Crofoot G, et al. Switching from efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disproxil fumarate to tenofovir alafenamide coformulated with rilpivirine and emtricitabine in virally suppressed adults with HIV-1 infection: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3b, non-inferiority study. Lancet HIV. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS guidelines, version 9.0. 2017.

- 20.Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry Steering Committee . Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry International Interim Report for 1 January 1989 through 31 January 2017. Wilmington: Registry Coordinating Center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.COMPLERA® (emtricitabine, rilpivirine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) [package insert]. Foster City: Gilead Sciences; 2016.

- 22.Towers CV, Rumney PJ, Ghamsary MG. Longitudinal study of CD4+ cell counts in HIV-negative pregnant patients. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(10):1091–1096. doi: 10.3109/14767050903580359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Notarianni LJ. Plasma protein binding of drugs in pregnancy and in neonates. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990;18(1):20–36. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199018010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.