INTRODUCTION

Anxiety is one of the most common symptoms seen in the elderly. Sub-syndromal anxiety is more prevalent than depression and cognitive disorders. The commonest anxiety disorder seen in the clinical practice is Generalised Anxiety Disorder(GAD)(7.3%) followed by phobias(3.1%), the panic disorder(1%) and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder(OCD)(0.6%). Two relatively recent Indian studies have demonstrated an overall prevalence of anxiety disorders to be10.8% and 10.7%, respectively. Thus anxiety is quite common in the elder, among all the disorders of the geriatric population.

These clinical practice guidelines intend to provide the practicing psychiatrists a ready reckoner to identify anxiety disorders, assess them, treat and manage side-effects of medications among elder individuals.

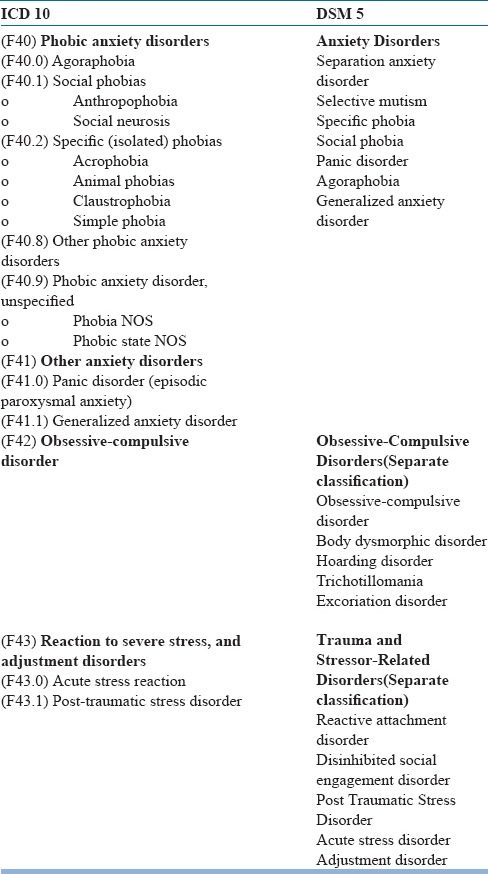

The classificatory systems (Table 1) now have a difference as far as anxiety disorders are concerned, with DSM 5 introducing changes in the classification of anxiety disorders.

Table 1.

Classificatory Systems for Anxiety Disorders

On the basis of their distinct clinical features anxiety disorders can be divided into three categories.

-

1)

Worry/distress disorders- GAD, PTSD, Acute stress disorder

-

2)

Fear disorders- Panic disorder, phobia

-

3)

OCD

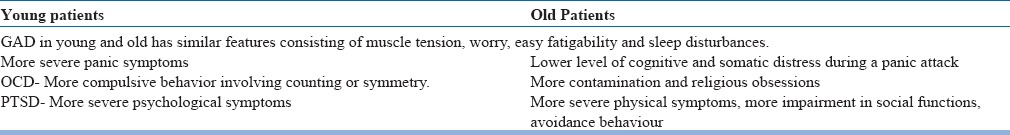

Since we are used to evaluating younger individuals, the usual symptoms we expect might not be seen in the elder. Commonly seen differences between the young and the old in the presentation of anxiety are shown in Table-2.

Table 2.

Differences in clinical presentation of anxiety disorders among young and elderly patients

Assessment

A comprehensive assessment of anxiety disorders includes interviewing the older adult and her/his caregiver. There is a tendency to underplay or normalize certain behaviours, which may be indicative of anxiety for e.g., avoidance to go out of the house or fear of falls. It is thus important to assess not only the severity of these symptoms; but also impairment in functioning because of the symptoms. This can be achieved by interviewing the patient and the caregiver, keeping the following in mind:

-

a)

Fears and concerns as a part of normal aging e. g. Limited mobility in an elderly leading to avoidance of going out of the house

-

b)

Anxiety associated with dementia

-

c)

Medical disorders which may mimic anxiety symptoms.

-

d)

Co-morbidities like cardiac illness, depression, malignancy, Parkinson's disease, auto-immune disorders, collagen vascular diseases, endocrine disorders etc.

-

e)

Clinical presentation in young adults and elderly differs. For e.g., in elderly phobia is experienced as a fear of situations or inanimate stimuli, such as lightening whereas among young people phobia is usually of animals.

-

f)

The ‘worried well’ Worry as a symptom in older adults, independent of a diagnosable disorder.

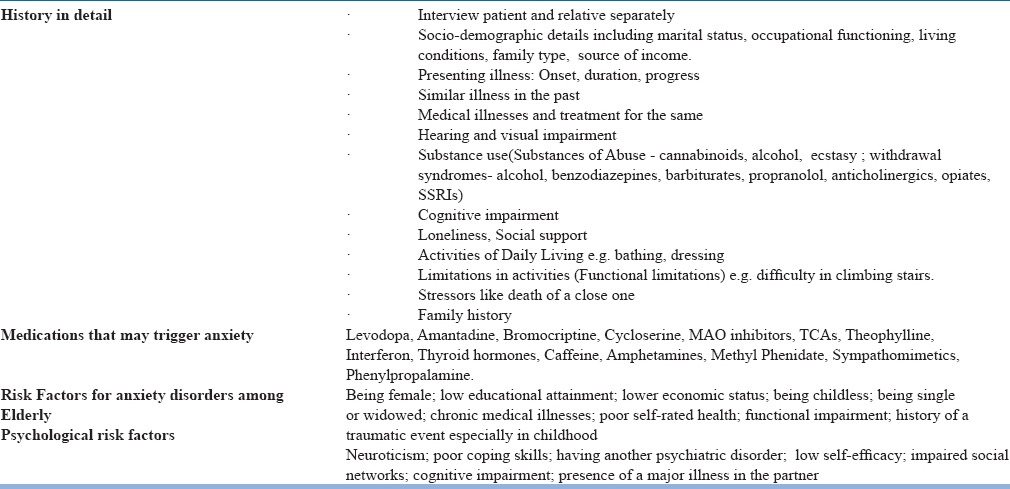

The hallmark of any complete assessment starts with a detailed history.

History: The following points (Table 3) need to be kept in mind while detailing a history of elder anxiety, to give a clearer picture. The basic history forms a base or a skeleton on which we have to build the further points which will lead us systematically towards a diagnosis. Elder individuals are considered to be a vulnerable population, and it is this vulnerability which makes them at risk to develop anxiety.

Table 3.

Pertinent issues in history while evaluating for Elder anxiety

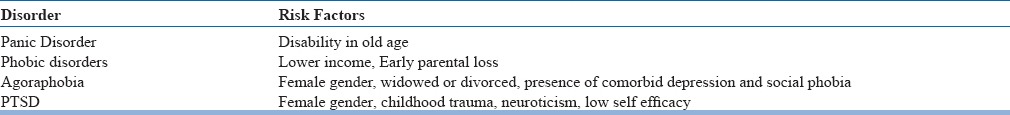

Multiple risk factors have been identified, which are known to be associated and specific anxiety disorders (Table-4).

Table 4.

Risk factors for various anxiety disorders in the elderly

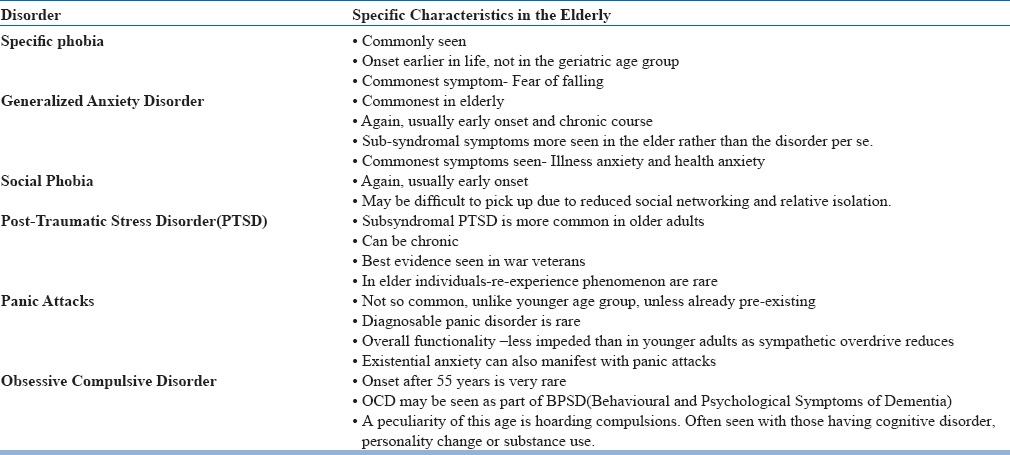

A comprehensive history and assessment of risk factors will be the most important ingredients towards making a diagnosis of the specific anxiety disorder that will emerge as a diagnosis. While narrowing down on the same, the specific characteristics that one can look for, in elder individuals, when one looks for the symptoms of various disorders, are highlighted below (Table 5). The disorders appear from common to uncommon, as seen from various population studies.

Table 5.

Specific presentations of various anxiety disorders in the elderly

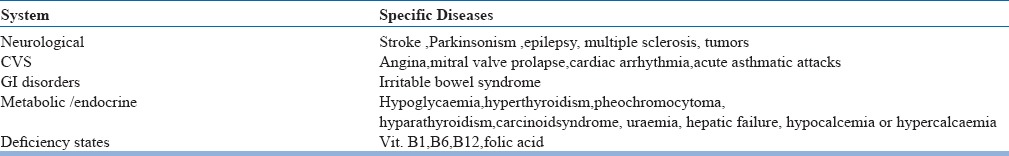

Any psychiatric history cannot be complete without the inclusion of negative history too. Anxiety is such a pervasive symptom, that it not only is seen in specific anxiety disorders, but can be seen in other psychiatric disorders, as well as many medical disorders (Table 6). An astute clinician will keep an eye out for the same, and eliminate that whilst taking the history.

Table 6.

Medical conditions in the elderly which can be mistaken for anxiety

It is not only medical disorders that one must rule out. Usually elder individuals are already on medications for medical co-morbidities, commonest being diabetes or hypertension. They may or may not be on analgesics too. There are some drugs and substances however, that are peculiar in contributing to anxiety. A red flag on any of these would point toward non-idiopathic anxiety, and prompt the treating psychiatrist to first alter the existing prescription, before staring yet another molecule and adding to the prescription load.

It becomes important to liaison with the treating physician/specialist to reduce/replace the suspected offending agent with another acceptable molecule

As one can see, the history, along with medical and drug history, can be quite exhaustive in the elderly, but to get a comprehensive account, it is very much worthwhile investing time into that.

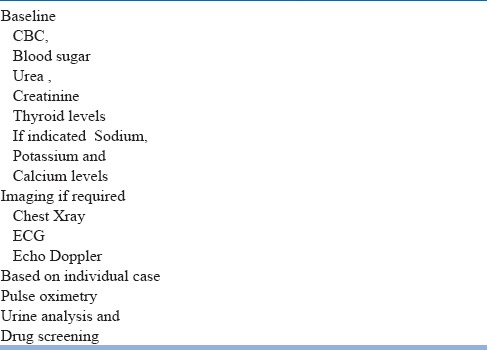

Investigations

Elder individuals are prone to changes in metabolic parameters and nutritional deficiencies, by virtue of a variety of reasons which include decreased appetite, increased frailty and drug-drug interactions. As a baseline, it is advisable to rule out metabolic abnormalities (Table 7) such as:

Table 7.

Investigations which may be done in a case of Elder Anxiety

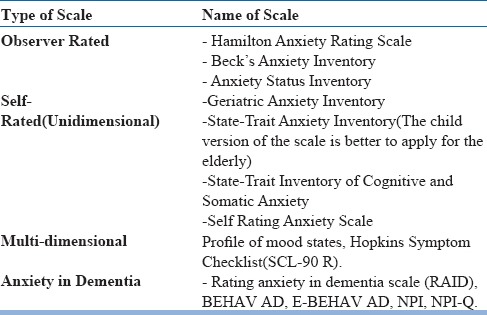

Once the basic medical work-up and evaluation is done, then a scale may be used to measure or quantify the anxiety, which would also aid as a prognostic indicator. Various anxiety rating scales (Table 8) have been used in elderly to substantiate the diagnosis and to assess severity of the disorder. These scales also assist in diagnosing anxiety symptoms not amounting to a disorder. This is particularly helpful as anxiety in elderly is under-diagnosed.

Table 8.

Rating Scales for Geriatric Anxiety

The choice of the scale would largely depend on the time and purpose that it is being used for.

The Geriatric Anxiety Inventory has become the gold standard for assessment in elder anxiety.

At the end of the above exercise, one would be sufficiently equipped with a preliminary diagnosis or differential diagnosis at the back of the mind.

Whilst we come to a definite diagnosis, the following differentials must be ruled out as these commonly will be the underlying cause of the anxiety, and our treatment may then show only a partial response.

Differential Diagnosis of Anxiety in Elder individuals(in order of likelihood)

Side Effects of Medication use, including self medication

Drug and alcohol use

Medical comorbidities

Other Psychiatric disorders(including cognitive disorders)

Trimming a prescription or changing medication might be a challenge initially, the tricky aspects at times are when one funnels down to a psychiatric diagnosis. Here, there are two pertinent issues which often crop up while assessing the elder individual for anxiety. These are:

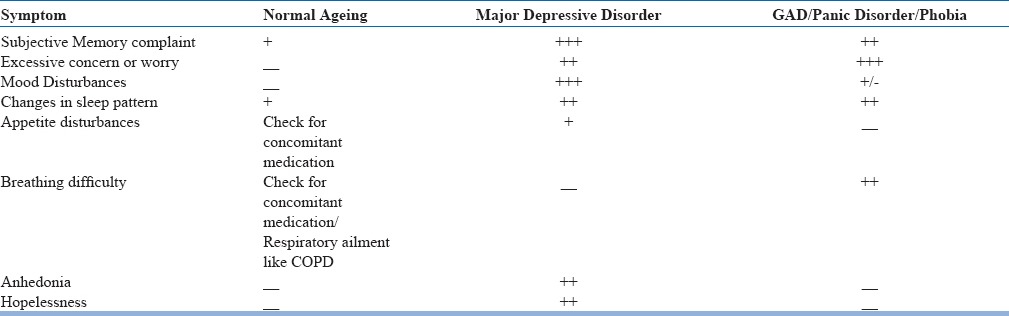

Distinguishing anxiety and depression in the elder (Table 9)

Table 9.

Comparative Symptom Overview for Normal Ageing versus Anxiety versus Depression in the Elder

This simple overview is very helpful in distinguishing the above

-

2.

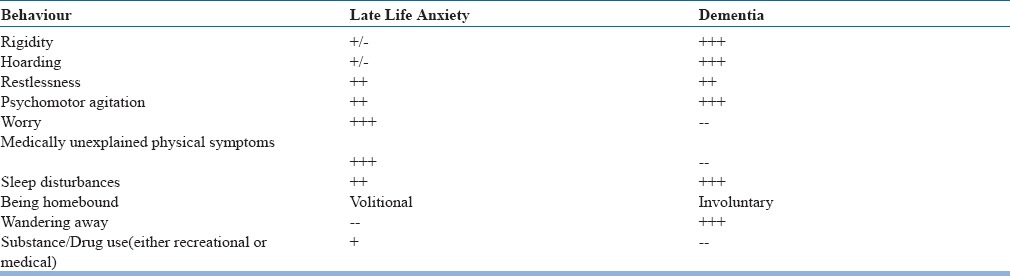

Distinguishing anxiety from cognition(Table 10)

Table 10.

Comparative Symptom Overview for Late Life Anxiety versus Dementia

Anxiety has reported high prevalence rates among people with dementia. It has a negative impact on cognitive impairment and is associated with agitation and poor quality of life. The presence of excessive anxiety can be difficult to establish in people with dementia, especially when expressive or receptive speech is impaired.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of research on the treatment of anxiety in dementia, and also on the wider issue of the management of anxiety disorders in old age. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia are not limited to the later stages of the disease.

The following comparative chart helps with clinical differentiation of the two.

Once one has been able to differentiate between normal ageing, anxiety, depression and a cognitive disorder or dementia, and come to a definitive diagnosis of anxiety - one can then proceed on deciding how to manage the patient.

Choice of treatment setting

Most of the anxiety disorders can be treated in outpatien setting.

Inpatient management of anxiety disorders is indicated when

-

1)

Comorbid severe depression(and at times suicidality) is present.

-

2)

Anxiety disorder is severe and treatment resistant. e.g. OCD.

-

3)

In case of poor social support and presence of chronic stressor separation from the stressful situation is needed.

-

4)

Concurrent medical illnesses and treatment need evaluation and management.

Non-Pharmacological treatments

Treatment of geriatric anxiety actually involves more of non-pharmacological approaches which are first recommended rather than pharmacological approaches. The usual non-pharmacological measures advised are:

Lifestyle modification: Sleep, diet, exercise, socialisation –all in moderation. Eliminate medical and non-medical triggers

Structured daily activities are one of the mainstays of elder care. The premise behind the same being, that activities provide some stimulation and interaction with the environment, give a sense of control and reduce overall anxiety. Apart from managing one's own daily routine, the following are commonly advocated.

-

a)

Physical Exercise: Regular physical exercise, even for just a few minutes daily, improves cerebral blood flow and metabolism. Sedentary individuals who are bound to their beds have a distinct reduction in cerebral blood flow. Exercise need not be strenuous in the form of aerobic exercises or gym based exercises. A simple walk in the garden or outdoors should suffice, that too at the pace of the individual concerned. If wheelchair bound, then upper body can be exercised with simple stretches, use of a ball and hand exercises.

Other forms of physical exercise could include

- Walking in the house if too frail

- Swimming or aqua exercises or playing around in a large tub to mobilize the limbs

- Physical games like playing ball, carrom, table tennis etc

-

b)

Sleep: We are aware that the sleep architecture gets altered with advancing age, hence a shorter night time sleep, phase advancement and more fragmented sleep are all seen in the elder. Hence while teaching about sleep hygiene, it is also important to counsel the elder individual about lowering their expectations about sleep duration.

-

c)

Nutrition: By virtue of decreasing appetite and increasing social isolation, elderly often have compromised nutrition and imbalanced electrolytes. Minor changes in blood levels of sodium, potassium, chloride, vitamin D etc. could give rise to anxiety symptoms. Monitoring through a simple nutrition chart, helps maintain basic parameters, and at times is the only intervention required to manage the anxiety.

-

2.

Behaviour Therapy:

-

a)Relaxation Therapy: Classical Jacobson's technique of progressive muscle relaxation can be taught to the individual with anxiety. This can also be coupled with guided imagery, or practiced alone.

-

b)Systemic desensitization : This works particularly for phobias and unspecified fears for eg. fear of falling. Creating a hierarchy and controlling the response helps.

-

c)Exposure and Response Prevention: For OCD

-

d)Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR): For PTSD.

-

a)

-

3.

Cognitive Therapy:

-

a)Cognitive Behaviour Therapy : The aim of CBT in older adults is to target cognitive symptoms, physical symptoms as well as behavioural symptoms. First and foremost psycho-education is a must –about the anxiety in general and management of the same. Acceptance that the symptoms may not be suggestive of a medical emergency, at the same time being vigilant of associated co-morbidities, becomes a tricky issue to deal with and require a lot of awareness and self-monitoring. The principles of relaxation and hierarchal construction may also be used. The core of CBT, however, remains cognitive restructuring using the ABC model(antecedents-behaviour-consequences), wherein cognitive errors and maladaptive behaviour are identified and worked upon. The pace may have to be a little slow, as with age new learning takes time, and the template of old learned behaviours is hard to change.

-

a)

-

4.

Mindfulness: Mindfulness as a therapeutic intervention is finding applicability in a wide range of disorders. Mindfulness is inculcating the ability to focus on ‘the now’. It involves focussing initially on individual senses for eg. taste, smell, vision, hearing etc. and then graduating to focussing on one's emotions, reactions, responses etc. The aim is to harmonise the difference between the mind and body. Mindfulness is particularly important in the elderly, where there are so many transitions taking place not only in the body, but also in the mind, social interactions and roles within the family as well as outside. All of these can contribute to and worsen anxiety. Mindfulness then becomes a very effective tool, under these circumstances.

-

5.

Miscellaneous-

-

a)Yoga : Based on the medical condition of the individual, various asanas can be taught. Yoga an also be done sitting on a chair, and not on the floor. More importantly relaxation, stretches and pranayamas can be taught to senior citizens. There is mounting evidence of control of elder anxiety with Yoga.

-

b)Art Therapy: Free art in the form of drawing, sketching or colouring as well as structured art in the form of following instructions, are both recommended. Art therapy can be planned as an individual or group activity. Art is said to be soothing and stimulates relaxation, which is paradoxical to anxiety.

-

c)Dance therapy: Dance as a structured art form, or free dance to music of one's choice both are advocated. Even for wheel chair bound and individuals confined to bed, movement of the upper body can help with some stimulation.

-

d)Music Therapy: Music as a form of environment modification has already been discussed. Music can also be used as an activity—either singing or playing an instrument. This can be done as individual therapy or in a group, though there is more evidence for group therapy.

-

e)Cognitive Rehabilitation: As much as the body needs physical exercises, the mind too needs to exercise itself. In our daily routine we do not even realize how much we use the brain for planning, sequencing and executing tasks. Cognitive training involves activities like sorting by colour, shape, sequence etc. It also involves memory games wherein memorizing by loci, chunking, pneumonics, visual imagery, su doku etc.

-

f)Social Activities or Networking : Interacting with others not only is an important stimulus, but it also improves synaptic connections between the neurons in the brain. Social activity can be within a small locus, or could be extended to external activities like meeting in a senior citizen's group, laughter clubs, book clubs, ‘satsangs’ etc.

-

g)Alternative Therapies: Complementary and alternative therapies like touch therapy, reflexology, massage, reiki etc have been tried with not very robust evidence. There are more of anecdotal reports of the same.

-

a)

While it is important to try out any of the above approaches, one must not forget to keep in mind the caregivers dealing with a patient of elder anxiety. Educating them about the illness, expectations, response etc. are equally important in the measure of overall response. Apart from information related to the illness per se, it is vital that they learn the art of communication, which can reduce the anxiety in the elder individual. A few do's and don'ts in this regard are:

Do's

-

a)

Talk in a neutral tone

-

b)

Use very simple words and sentences. And speak slowly.

-

c)

If instructing, please give one instruction at a time

-

d)

If asking for something, please give maximally two choices at a time

Don'ts

-

a)

Use a harsh tone or voice

-

b)

Use negative words or derogatory remarks

-

c)

Lose your patience

Having a supportive and encouraging caregiver, is half the battle won. A stay at home caregiver can even learn most of the therapies by themselves, and minimize therapists visits.

However, if a trial of the above non-pharmacological methods does not succeed, or the anxiety is too severe, then pharmacological treatment can be initiated, but is lowest possible doses for as short a duration as possible.

Pharmacological management

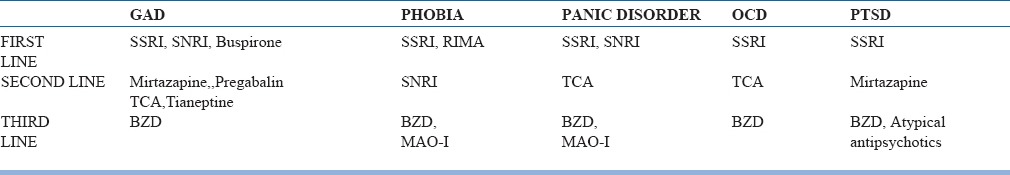

SSRI's top the list of first line drugs(Table 11) across the various disorders. Usually, failure of response leads to trial with an SNRI, and then the rest of the drugs follow. Benzodiazepines should be restricted to short term use, and quickly tapered, owing to multiple problems that they may lead to in the elderly.

Table 11.

Treatment Overview

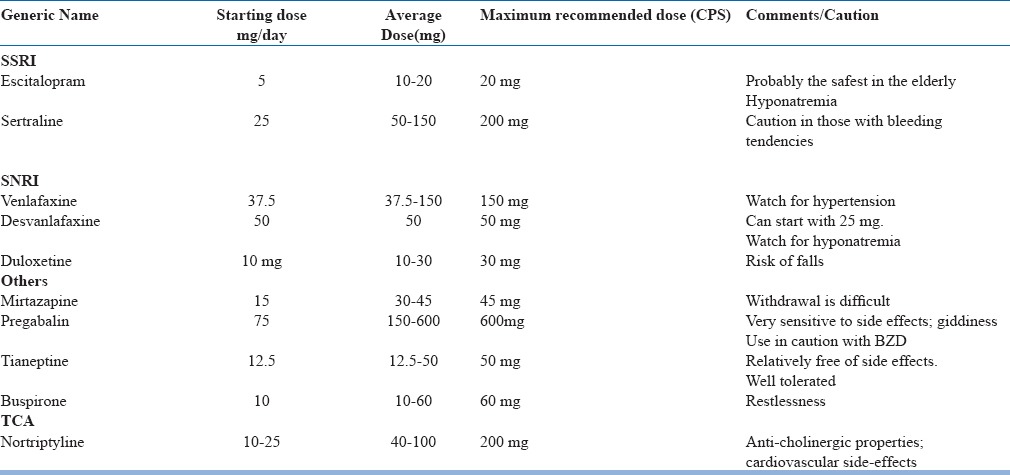

While choosing a pharmacological agent, it is always preferable to follow the thumb rule—start low, go slow and titrate upto usually half of the adult dose.

Commonly, the following doses (Table 12) are recommended:

Table 12.

Dosing strategies for commonly used Antidepressant Medications

It is advisable to continue treatment for 4-12 weeks(longer for OCD and PTSD, before a response is expected). The above can be combined with benzodiazepines, but with use of both benzodiazepines as well as non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists preferably should be limited to 2-4 weeks in the initial period only. Both are associated with increased risk of falls, dissociative phenomena and confusion in the elderly.

Elderly in fact are quite sensitive to benzodiazepines, which have neuro-cognitive effects in them, similar to alcohol. There use can also cause paradoxical agitation. Hence as far as possible we should avoid using them, but when required use in very low doses and taper them quickly.

There are certain indications for benzodiazepines in the elderly too-like alcohol withdrawal, pre-operative anaesthesia, seizures and in very severe anxiety. However here too, it is preferable to start with lower doses, and quickly taper.

Should there be no response with the first line of medications, then the second line can be tried either as monotherapy i.e switch to the given drug of another class or augment. The details of the same are discussed under specific anxiety disorders.

Other modalities of treatment

Modalities of treatment like. rTMS, tDCS have been tried in a few studies of anxiety disorders in adult patients, but similar studies in elderly patients have not been done. However rTMS has been shown to be useful in resistant geriatric depression and it has been observed in these patients that concurrent anxiety symptoms also improve. Further research is needed in this area to establish these treatment modalities in anxiety disorders.

Managing Side –effects

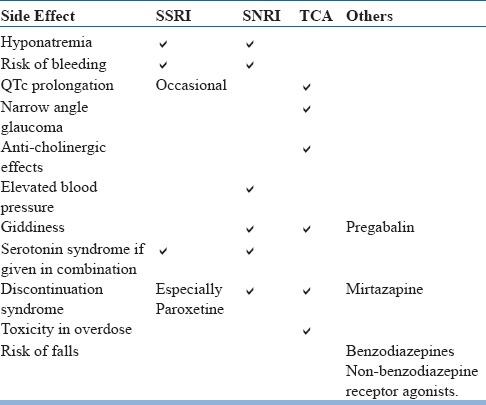

As the elder are more sensitive to side effects of most medication, it is important for us to know of the common side effects (Table 13) of the commonly prescribed anti-anxiety medications, so we can keep a vigil on the same. The overview below serves as a quick checklist.

Table 13.

Common Side effects of medication seen in elderly

There are two challenging side effects, commonly seen, which are often difficult to deal with and manage. These are:

1] Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia is defined as a level of serum sodium below 135 mmol/l and is considered to be severe if it is below 120mmol/l. Usually below 130mmol/l would lead to nausea and malaise and the elderly seem to be more prone to even small changes in sodium levels. Below 115 mmol/l cn be life threatening, leading to headache, disorientation, seizures, coma, respiratory depression and even death.

Hyponatremia may be acute or chronic, or due to osmotic demyelination. In chronic hyponatremia, there are increased chances of falls due to two reasons-

-

a)

Increase lethargy and confusion due to CNS impairment

-

b)

Increased osteoclastic activity and decreased bone mineralization leading to osteoporosis and frail bones, which predispose to falls.

Hence it is important that hyponatremia is corrected at the earliest. In order to correct it, one should ascertain whether the hyponatremia is

-

i)

Dilutional: a) Hypervolemic(oedema) secondary to heart disease, nephritic syndrome, cirrhosis

-

b)

Euvolemic(no oedema) SIADH—which may be idiopathic of drug induced; hypothyroidism, secondary renal insufficiency

-

ii)Depletional : Secondary to volume loss—burns, vomiting, trauma, diuretics, pancreatitis, primary renal insufficiency.

-

ii)

In order to determine the cause, in addition to the sodium levels, the total urine volume(24 hour) along with serum and urine osmolality will give a clue. In addition tests of thyroid and adrenal function may be done.

Once the cause is determined the approach is fairly standard:

- Remove the offending molecule if it is drug induced. SSRI's are notorious for causing the same in the elderly, and along with correction, the offending molecule should be replaced.

- Correct sodium levels by addition of sodium (by standard formulae for correction)

- Reduce total volume by fluid restriction, demeclocylcine, vasopressin receptor antagonists etc.

2] Another very specific issue is managing benzodiazepine abuse or dependence

Benzodiazepine Abuse is usually seen in two patterns

Non-medical or recreational abuse (to ‘feel good’)

Partial dependence due to quasi-therapeutic use - long-term drug taking inconsistent with accepted medicalpractice and at the same dose.

Benzodiazepine abuse may be approached in two steps:

A] Detoxification

1. Traditional Taper Method

Initially substitute with a longer acting BZD. Then start tapering. Elder individuals may be sensitive to the side effects and emergent paradoxical reactions with BZD, and this becomes pronounced with longer acting molecules, hence caution is advised.

The rule of thumb is 10% reduction till half the original dose is reached, then 5% reduction till one-fourth the original dose is reached, then 2.5 % reduction till 0.5 mg is reached and then slowly increase the gap and gradually stop. For eg. If 20 mg of diazepam is the substituted molecule, reduce by 2 mg daily, till 10 mg is reached. Then reduce by 1 mg daily till 5mg is reached. After this dose the next steps have to be largely individualized. Then reduction can be by 0.5 mg daily/alternate days/twice a week depending on the patient response; till 0.5 mg is reached. Once 0.5 mg is reached start increasing the gap between the doses i.e alternate days, then thrice a week, then twice a week then stop.

The response to tapering depends on

Individual patients

Setting-outpatient more difficult to monitor

Better if previous use was for therapeutic reasons

Co-morbid medications

Acceptance of need to abstain by the patient i.e patient contract

-

2.

Alternate method: Substitution to once daily dosing of long acting BZD, taper over 4 weeks and stop.

B] Adjuvant pharamacotherapy-

In order to deal with the anticipated withdrawal syndrome, anticonvulsants like Carbamazepine, Gabapentin, Valproic acid may be used for about two weeks. In addition, propranolol or anti-histaminics may also be tried for a period of two weeks.

Treatment End Point

It is recommended that the duration of treatment should be a minimum of 12 months starting from the time of remission (and up to 2 years).

If the decision is made to stop medication, the dose should be reduced over several months with monitoring for relapse. Monitoring should be done 3-6 monthly keeping two things in mind:

-

a)

Remission/and or exacerbation of anxiety

-

b)

Emergent cognitive symptoms

Specific Disorders

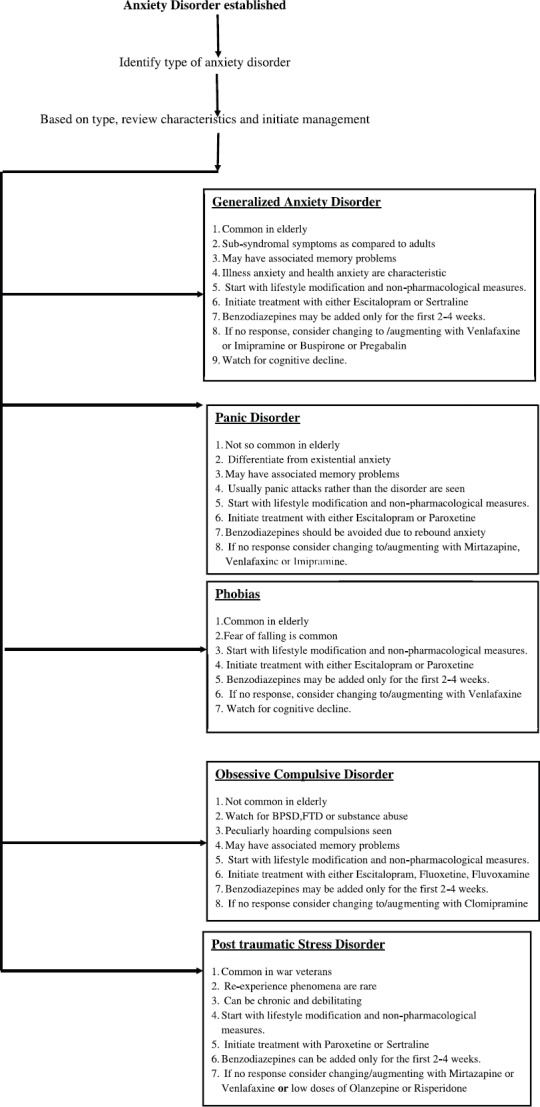

If we have to summarize the overall management and divide it according to the various anxiety disorders in the elderly, the following guideline may be useful (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1.

Anxiety Disorder established

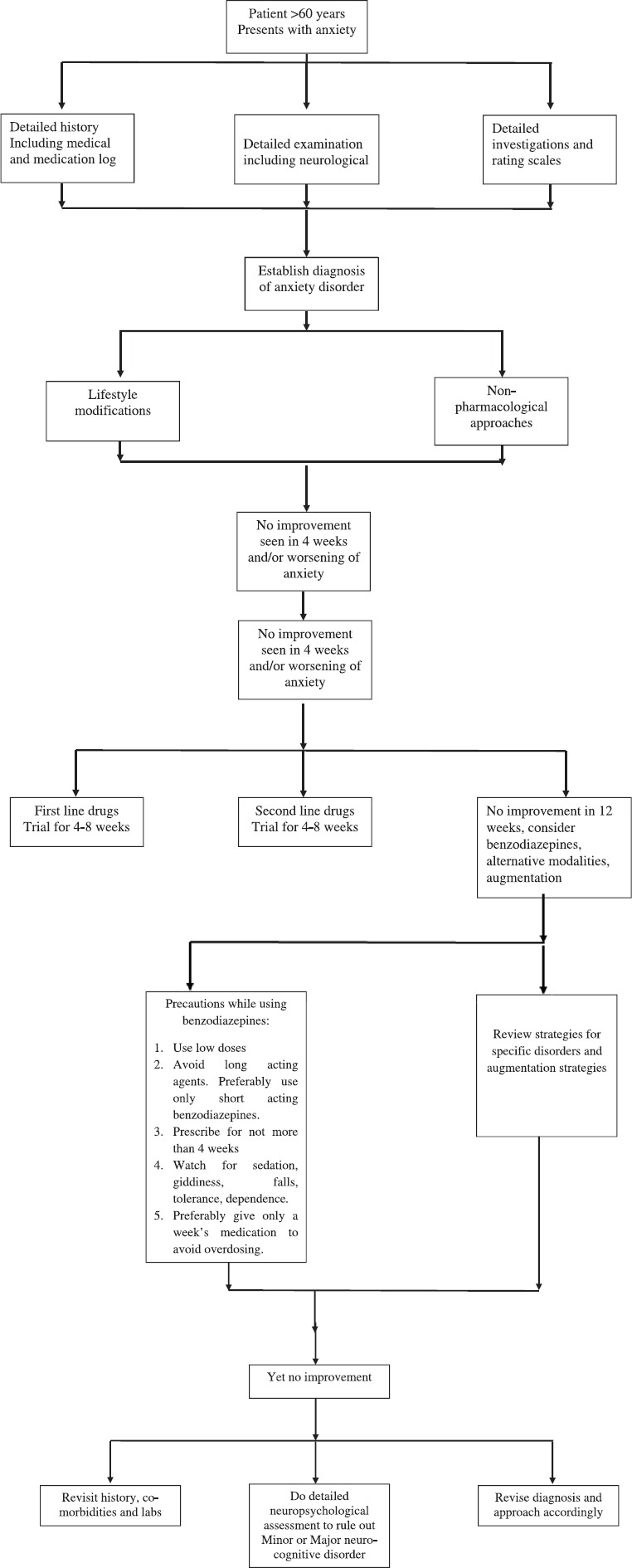

Fig. 2.

Overview of approach to an elder individual with anxiety

Identify type of anxiety disorder

Based on type, review characteristics and initiate management

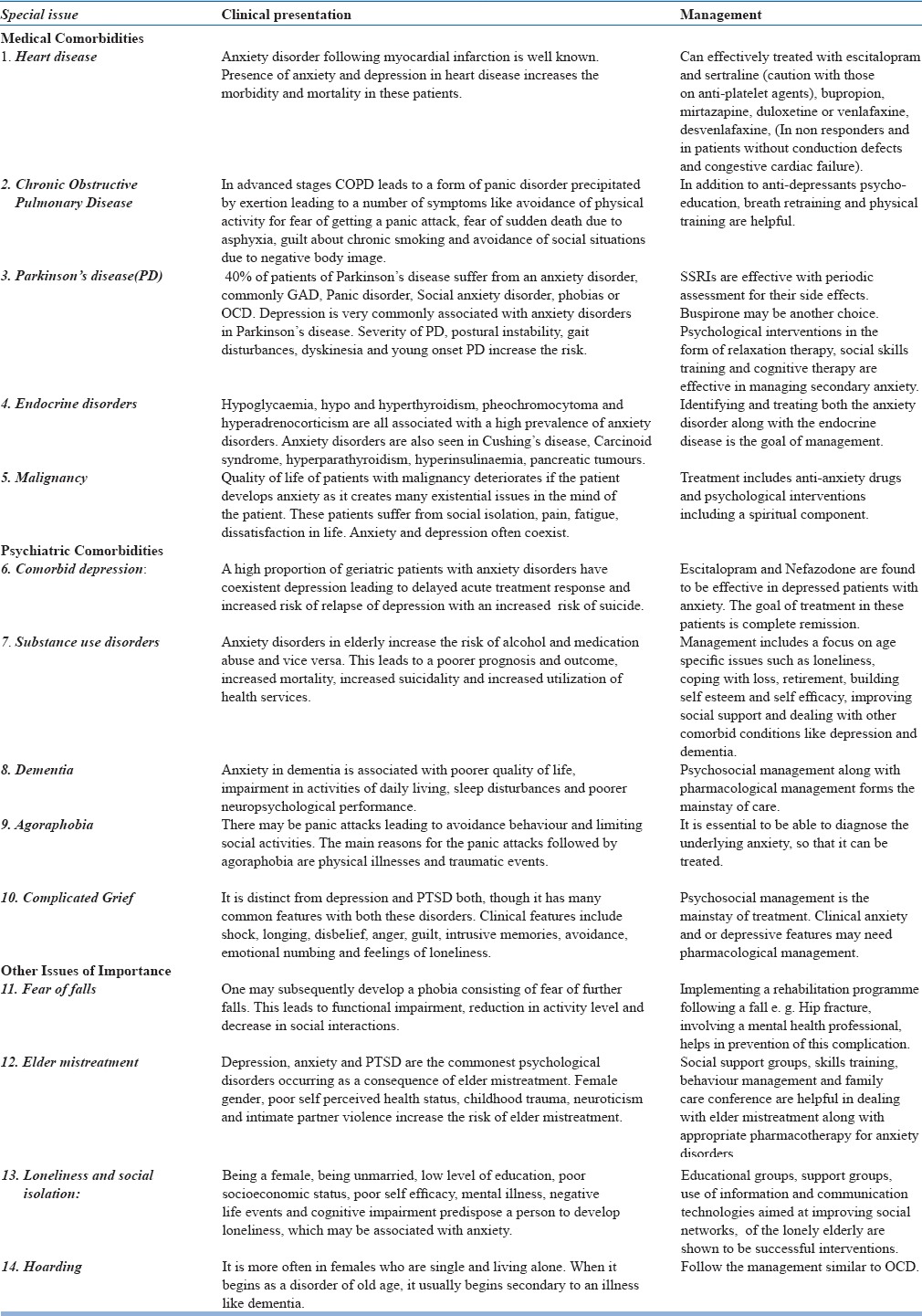

Special Issues

Treatment of anxiety disorders in elderly is complicated by comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions and multiple medications that these patients may be receiving. Certain medical illnesses in older individuals require special mention, as may lead to anxiety disorders (Table 14)

Table 14.

Issues of Special Concern.

Conflict of Interest: Nil

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Gellis Zvi D, Stanley G. McCracken. “Advanced MSW curriculum in mental health and aging”. CSWE Gero-Ed Center. 2008. Available at www.gero-edcenter.org .

- 2.Ravi Soni. Demography and Epidemiology of Psychiatric Disorders in the Elderly. Health and Medicine. 2014. Oct 2nd, accessed from http://www.slideshare.net .

- 3.Chowdhury A, Rasania S. A Community Based Study Of Psychiatric Disorders Among The Elderly Living In Delhi. The Internet Journal of Health. 2007;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sreejith S. Nair, Pooja Raghunath, Sreekanth S. Nair. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders among the Rural Geriatric Population: A Pilot Study in Karnataka, India. Central Asian Journal of Global Health. 2015;4(1) doi: 10.5195/cajgh.2015.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elaine Kwan, Chanaka Wijeratne. Presentations of Anxiety in Older People. Medicine Today. 2016;17(12):34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keri-Leigh Cassidy, MD, Neil A. Rector., PhD The Silent Geriatric Giant: Anxiety Disorders in Late Life. Geriatrics and Aging. 2008;11(3):150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 7.CANADIAN NETWORK For MOOD And ANXIETY TREATMENTS (CANMAT.ORG) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beattie E, Pachana N, Franklin S. Double Jeopardy: Comorbid Anxiety and Depression in Late Life. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2010;3(3):209–220. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20100528-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnie S. Wiese. Geriatric depression: The use of antidepressants in the elderly. BCMJ. 2011 Sep;53(7):341–347. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campanelli C. M. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults: The American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(4):616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Sarkar S. Benzodiazepine abuse among the elderly. J Geriatr Ment Health. 2016;3:123–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diefenbach G J, Goethe J. Clinical Interventions for Late-Life Anxious Depression. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2006;1(1):41–50. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soiza RL, Hannah S.C. Talbot Management of hyponatraemia in older people: old threats and new opportunities. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2(1):9–17. doi: 10.1177/2042098610394233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleakley S. The pharmacological management of anxiety disorders. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. pp. 15–20. Accessed through www.progressnp.com .

- 15.Orgeta V, Qazi A, Spector AE, Orrell M. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in dementia andmild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009125.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olthuis JV, Watt MC, Bailey K, Hayden JA, Stewart SH. Therapist-supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011565.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LenzeEric J. Blazer Dan G, Steffens David C, editors. Wetherell Julie Loebach Anxiety disorders, in Textbook of Geriatric Psychiatry. The American Psychiatic Publishing. (4th edition) :333–345. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wetherell Julie Loebach, Stein Murray B. Anxiety disorders in chapter Geriatric Psychiatry in Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. In: Sadock Benjamin, Sadock Virginia, Ruiz Pedro., editors. 9th Edition. Wolters Kluwer: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; pp. 4040–4047. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katzman Martin A, Bleau Pierre, Chokka Pratap, et al. Canadian Clinical Practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stojanovic J, Collamati A, Mariusz D, et al. Decreasing Loneliness and social isolation among the older people: systematic research and narrative review. Epi Biostat and Pub Health. 2017;14(2)(Suupl 1):e12408-1–e12408-8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong Xin Qi, Chen RuiJia, Chang E-Shien, et al. Elder abuse and psychological well being: A systematic review and implications for research and policy- a mini review. Gerontology. 2013;59:132–142. doi: 10.1159/000341652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong Xin Qi. Elder abuse: a systematic review and implications for practice. JAGS. 2015;63:1214–1238. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuurmans J, Balkom A. Late life anxiety disorders: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(4):267–73. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tampi R, Tampi D. Anxiety disorders in late life: A comprehensive review. Healthy aging Research. 2014;3:14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh K, Bennett G. Parkinson's disease and anxiety. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:89–93. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.904.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wison K, Chochinov H, Skirko G. Depression and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. J pain and Symp Management. 2007;33(2):118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall R, Hall R. Anxiety and endocrine disease. Semin in clin neuropsychiatry. 1999;4(2):72–83. doi: 10.1053/SCNP00400072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ascott- Evans B, Kinvig T. Endocrine disorders in the elderly. Endo Dis. 2004;22(11):623–628. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dissananyaka N Sellbach A, Matheson S. Anxiety disorders in Parkinson's disease: Prevalence and risk factors. Mov Dis. 201;25(7):838–845. doi: 10.1002/mds.22833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Hara, Beaudreau Late-Life Anxiety and Cognitive Impairment: A Review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 Oct;16:10. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31817945c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chattopadhyay K, Singh AP. Anxiety and its impact on quality of life among urban elderly population in India: An exploratory study. Indian J Res Homoeopathy. 2016;10:133–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syed Elias SM, Neville CC, Scott TL. The effectiveness of group reminiscence therapy for loneliness, anxiety and depression in older adults in long-term care. Asystematic review Geriatric Nursing. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]