Abstract

Current Neuroscience dogma holds that transections or ablations of a segment of peripheral nerves produce: (1) Immediate loss of axonal continuity, sensory signaling, and motor control; (2) Wallerian rapid (1–3 days) degeneration of severed distal axons, muscle atrophy, and poor behavioral recovery after many months (if ever, after ablations) by slowly-regenerating (1 mm/d), proximal-stump outgrowths that must specifically reinnervate denervated targets; (3) Poor acceptance of microsutured nerve allografts, even if tissue-matched and immune-suppressed. Repair of transections/ablations by neurorrhaphy and well-specified-sequences of PEG-fusion solutions (one containing polyethylene glycol, PEG) successfully address these problems. However, conundrums and confusions regarding unorthodox and dramatic results of PEG-fusion repair in animal model systems often lead to misunderstandings. For example, (1) Axonal continuity and signaling is re-established within minutes by non-specifically PEG-fusing (connecting) severed motor and sensory axons across each lesion site, but remarkable behavioral recovery to near-unoperated levels takes several weeks; (2) Many distal stumps of inappropriately-reconnected, PEG-fused axons do not ever (Wallerian) degenerate and continuously innervate muscle fibers that undergo much less atrophy than otherwise-denervated muscle fibers; (3) Host rats do not reject PEG-fused donor nerve allografts in a non-immuno-privileged environment with no tissue matching or immunosuppression; (4) PEG fuses apposed open axonal ends or seals each shut (thereby preventing PEG-fusion), depending on the experimental protocol; (5) PEG-fusion protocols produce similar results in animal model systems and early human case studies. Hence, iconoclastic PEG-fusion data appropriately understood might provoke a re-thinking of some Neuroscience dogma and a paradigm shift in clinical treatment of peripheral nerve injuries.

Keywords: axonal repair, axotomy, Wallerian degeneration, polyethylene glycol, allograft, autograft, nerve regeneration

Current Expectations for Complete Transection or Ablated Segment of a Peripheral Nerve

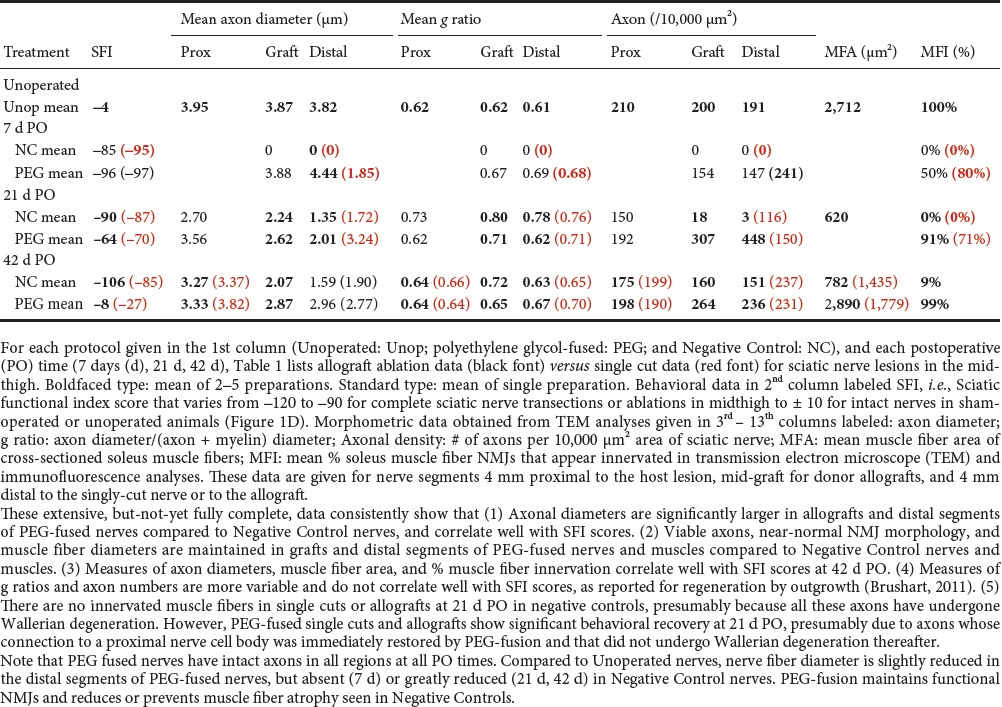

Peripheral nerve injury (PNI) is the most common nerve trauma, the consequences of which significantly burden Health Care Systems in civilian and military populations. PNIs that occur clinically as either complete transections or ablations of a segment of a major nerve often exhibit very poor, if any, behavioral recovery with contemporary clinical practice. Immediately after these PNIs, motor and sensory function distal to the injury is completely lost due to interrupted axonal continuity distal to the lesion. Thereafter, the distal portions of axons always and irreversibly undergo Wallerian degeneration within 1–3 days. Protracted functional recovery can occur only via slowly (1–2 mm/day) regenerating outgrowths from surviving proximal axons that often very inaccurately (non-specifically) reinnervate target tissues that may atrophy before reinnervation occurs, especially after ablation of a segment of a major nerve (Figure 1 and Table 1 (Brushart, 2011; Green and Wolfe, 2011; Kandel et al., 2013; Riley et al., 2015; Bittner et al., 2016)

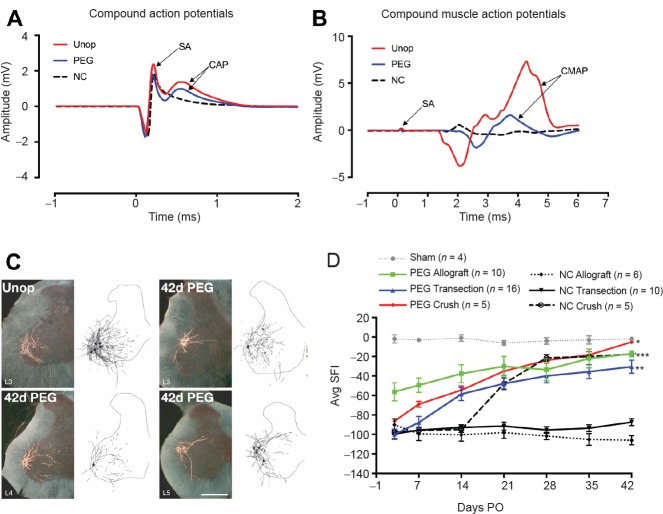

Figure 1.

Electrophysiological, morphologicical and behavioral results of PEG-fusion.

(A, B) Electrophysiological evidence of sciatic nerve continuity within 5 minutes after successful allograft PEG-fusion. (A) CAP (mV) recordings after ablating a 1 cm segment, insertion of a > 1 cm donor segment without (NC: black dashed line) or with PEG-fusion (PEG: blue solid line) of both severed ends microsutured to the proximal or distal ends of the host sciatic nerve. CAP arrow: peak amplitude. As one essential positive control for immediate viability and success of PEG-fusion, we always extracellularly generate action potentials in sciatic nerves in the upper thigh proximal to all lesion sites and extracellularly record those CAPs conducted to the lower leg in all animals prior to, and after, any PEG-fusion procedure (Unop and PEG traces). (B) Through-conduction of CAPs across sites of PEG-fusion is often associated with a twitch and a CMAP of muscles in the calf and foot. Through-conduction of CAPs is lost after single cuts or 0.5–1 cm ablations in the mid-thigh and is not restored unless a lesion is successfully PEG-fused (NC in Figure 1A). Within minutes, PEG-fusion restores through-conducting CAPs from upper thigh to lower limb, as well as twitching and CMAPs of muscles in the calf and foot. CAP amplitudes after PEG-fusion are typically not as large when compared to CAPs initially recorded from the intact nerve, i.e., CAPs are a binary measure of PEG-fusion success because CAP amplitude depends on many variables including electrode placement. CAPs or CMAPs recorded at the time of initial PEG-fusion are not a measure of long-term PEG-fusion success because the PEG-fused ends can separate if not properly microsutured once the animal starts to use the orated limb. CAPs are a much better measure of initial success than CMAPs because CMAPs can be produced in the absence of direct innervation by ephaptic current spread.

(C) Darkfield digital micrographs and matching computer-generated composites of transverse hemisections through the lumbar spinal cords of an intact control rat (unop), and a rat with a PEG-fused sciatic nerve allograft at postoperative (PO) day 42 (42 d PEG) following injection of horseradish peroxidase conjugated to the cholera toxin B subunit (BHRP) into the anterior tibialis muscle. Computer-generated (Neurolucida, MBF Bioscience) composites of BHRP-labeled somata and processes were drawn at 480 μm intervals through the entire rostrocaudal extent of the tibialis motor pool. In the unoperated animal, motoneuron labeling is restricted to the lumbar (L) 3 spinal segment. In the PEG-fused animal, labeled motoneurons are present in the L3 segment, but are now also found in the L4 and L5 segments; L4/5 motoneurons typically innervate other muscles of the lower leg and intrinsic foot muscles, but now project to the anterior tibialis. That is, reinnervation by continuously surviving PEG-fused motoneurons with inappropriate spinal to peripheral connections are somehow producing dramatically better behavioral recovery than is ever produced by motoneurons that re-innervate by slowly regenerating outgrowths that presumably must make appropriate connections to restore any lost behavior. Scale bar: 500 μm. (D) Behavioral recovery results as measured by the SFI test for 42 days PO after various surgical procedures in the mid-thigh to rat sciatic nerves as abbreviated in key for mean ± SE scores for (1) Sham operations in which the sciatic nerve is not cut (dotted gray line). (2) Allografts microsutured and PEG-fused after lesioning (solid green line). (3) Single cuts (transections) microsutured and PEG-fused (solid blue line); (4) Single Crush 1–2 mm long made with microforceps and PEG-fused (solid red line). (5) Single Crush 1–2 mm long made with microforceps but no PEG is applied (dotted black line). (6) Single cuts microsutured but no PEG is applied (solid black line). (7) Allografts microsutured but no PEG is applied (dashed black line). SFI scores are usually 0 ± 10 for unoperated animals and –90 to –110 for animals with a complete sciatic transection or ablation of a segment. SFIs for PEG-fusion protocols differ significantly from negative controls, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (detected by one way analysis of variance). Note that in the absence of application of a PEG-containing aqueous solution that behavioral recovery is very poor except for 1–2 mm crush lesions made by microforceps that leave endoneurial sheaths intact/continuous from proximal to distal across the lesion site. This short-length experimental crush lesion made by neuroscientists in mice or rats is essentially impossible to produce naturally in a large mammal and is never seen by clinicians (Green and Wolfe, 2011).

PEG: Polyethylene glycol; SA: stimulus artifact; Unop: Unoperated; NC: negative controls; CAP: compound action potentials; CMAP: compound muscle action potentials.

Table 1.

Summary of means for single cut and allograft axonal morphometric data

The standard of care for a transection PNI is to reappose and microsuture the cut ends (Brushart, 2011; Green and Wolfe, 2011; Kandel et al., 2013). An ablation PNI is currently repaired by microsuturing surgically inserted 1) autografts harvested from other body regions; 2) non-viable (non-immunogenic) conduits; or 3) decellularized allograft nerve segments, each of which acts as a bridge to distal nerve tissue. These current techniques often do not prevent Wallerian degeneration and do not improve the speed nor quality of behavioral recovery, if any. Limb amputation is often an acceptable or better alternative after loss of a nerve segment (Brushart, 2011; Green and Wolfe, 2011; Kandel et al., 2013; Riley et al., 2015). Viable donor allografts as a possible alternative are rapidly rejected even with immunosuppression and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) matching, primarily because of T cell adaptive responses and secondarily because of innate antigen-independent pro-inflammatory events (Murphy and Weaver, 2016).

In contrast, we have recently published data showing that repair of transected nerves or ablated segments of nerve trunks by PEG-fusion produces dramatically better morphological, electrophysiological and (most relevant) behavioral recoveries than any other currently-available procedure (Bittner et al., 2012, 2016, 2017; Ghergherehchi et al., 2016).

PEG-Fusion Results for Complete Transection or Ablated Segment of a Peripheral Nerve

PEG-fusion protocols consist of a well-specified sequence of solutions directly applied to well-trimmed, open axonal cut ends that are closely apposed by microsutures through the connective-tissue epineurium to provide mechanical strength to PEG-fused axons (see Figure 4 from Bittner et al., 2016). In brief, 50% w/w 2–5 kDa PEG/distilled water removes plasmalemmal-bound water to induce lipids in the apposed axolemmas of open axonal ends to produce axolemmal continuity (fuse) across the lesion site. Intact and repaired axolemmas have very low tensile strength/resistance to stretching.

Our laboratories have much published and other data documented in part in Figure 1 and Table 1 showing that after PEG-fusion axolemmal and axoplasmic continuity is rapidly (within minutes) restored as assessed by conduction of extracellularly-recorded compound action potentials (CAPs) (Figure 1A) and intracellular dye diffusion in both directions across the lesion site(s). Compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) also confirm such continuity (Figure 1B). Proximal and distal ends of motor or sensory axons are non-specifically connected (Figure 1C) and motor axons can be fused to sensory axons. Nevertheless, the following morphological, cell biological, and functional events are consistently obtained (Bittner et al., 2012, 2016, 2017; Riley et al., 2015; Ghergherehchi et al., 2016):

1) Fast axonal transport between cell bodies and distal motor nerve junctions or sensory nerve endings is restored days (single cuts) or weeks (ablations) after PEG-fusing single cuts and/or allografts, thereby supplying host proteins to all regions of the axon, as demonstrated by retrograde transport of tracers (Figure 1C). 2) Survival of distal segments of many transected axons or donor graft axons is continuously maintained from 0–150 days PO for single cuts and allografts, i.e., reducing or preventing axonal Wallerian degeneration, as assessed by photon microscopy and transmission electron microscope (TEM) of cross and longitudinal sections (Table 1). 3) Neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) are continuously maintained, as measured by confocal immunohistochemistry, TEM and counts of innervated muscle fibers (Table 1). 4) Muscle fibers are continuously maintained and often undergo very little atrophy, as assessed by TEM (Table 1). 5) Function/behavioral recovery is restored within days to weeks and approaches or equals that of unoperated animals as measured by the Sciatic Functional Index (SFI), especially for PEG-fused allografts. The SFI is a commonly used behavioral measure primarily determined by fine control of distal muscle masses responsible for toe spread and foot placement (Figure 1D and Table 1). Note that we always analyze the structure and function of nerves, muscles, myelin, and NMJs. However, we always define successful PEG-fusion repair by behavioral measures, not axon counts or any other morphological or electrophysiological measure, as Brushart (2011) has emphasized.

Remarkably, PEG-fused allografts are not rejected as assessed by photon microscopy, TEM, histological or immuno-histochemical methods: This is important because unlike brain or spinal nerves, mammalian peripheral nerves are in a non-immunoprivileged environment as are hearts, livers and kidneys (Murphy and Weaver, 2016).

Conundrums and Confusions Regarding PEG- Fusion

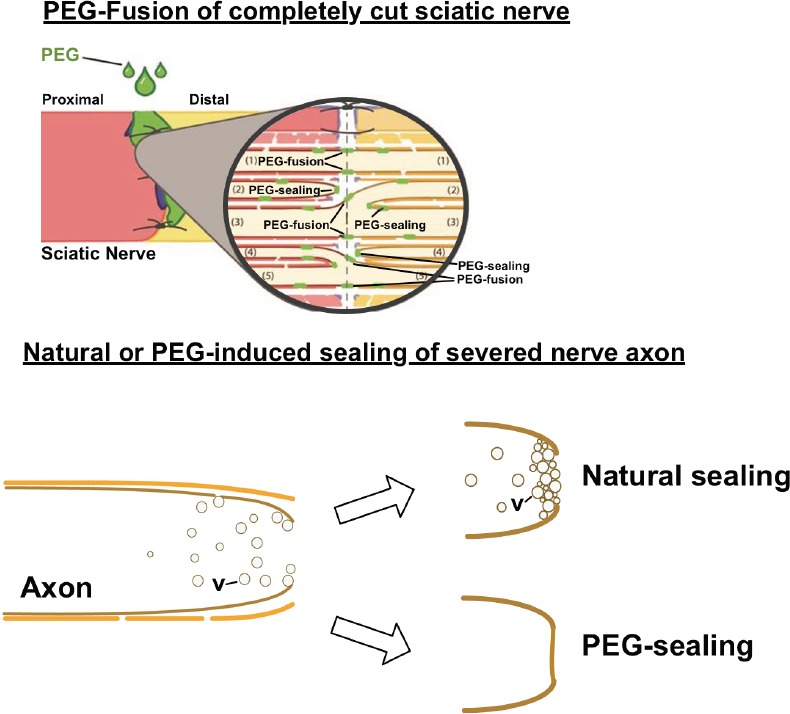

Some results of PEG-fusion present unexpected conundrums and/or are contrary to neuroscience (Kandel et al., 2013) or immunology (Murphy and Weaver, 2016) textbook dogma and hence lead to confusion (e.g., Robinson and Madison, 2016). As one example, some do not recognize or understand that when used in different circumstances or formulations, PEG can produce either membrane fusion (Bittner et al., 2016, 2017), membrane sealing (Spaeth et al., 2012) or cell protection (Kwon et al., 2009). In particular, our 2–5 kDa PEG dissolved in distilled water in a 50% w/w solution causes the closely apposed membranes of open cut axon ends to flow into each other (fuse) to join (repair) the cut, aka “PEG-fusion” (Figure 2; also see Figure 4 in Bittner et al., 2016). However, if the cut ends are not closely apposed, the PEG solution causes the axolemma at the open axonal ends to collapse, fuse, and seal-off (“PEG-sealing”) (Figure 2; Spaeth et al., 2012). These collapsed and sealed cut ends are very difficult to PEG-fuse unless recut and opened (Ghergherehchi et al., 2016). Alternatively, PEG used in synthetic hydrogels or in high (e.g., 15 kDa) molecular weight polymers may have some neuroprotective effects by unknown mechanisms (Kwon et al., 2009). Lower kDa PEG polymers may have some neuroprotective effects due to PEG-sealing, but if so, not by PEG-fusion. PEG applied to crushed segments of peripheral nerves produces a slight increase in recovery compared to recovery if nothing is done because the PEG causes PEG-sealing (rather than PEG-fusion). To produce good recovery using PEG, the crushed segments of such nerves almost certainly need be ablated and an allograft inserted and PEG-fused.

Figure 2.

PEG produces fusion of proximal and distal axons if their open, vesicle-free, cut ends are brought into close apposition by microsutures (“PEG-fusion”).

If axonal ends are not brought into close apposition, PEG causes the membranes at the cut ends to collapse and seal (“PEG-sealing”). If axons are completely cut, a Ca2+-induced accumulation of vesicles (v) occurs naturally to form a plug that seals the severed cut end--or any small hole in an axolemma (Spaeth et al., 2012; Bittner et al., 2016).

As a second example, PEG-fusion in each animal has its own unique characteristics due to nerve anatomy, exact lesion site, length of ablation, skill of the surgeon on that day, etc., as does surgery on a sciatic nerve in each human patient. That is, results fall within a range of recoveries, rather than exactly the same recovery SFI at each tested day for each animal (see Figure 5 in Ghergherehchi et al., 2016; See Figure 3 in Riley et al., 2015). The excellent behavioral recoveries seen after PEG-fusion compared to the poor or no recovery seen in Negative Controls are for transected or ablated PNI's in a proximal major nerve (mid-thigh sciatic lesions in rats). Short length (1–3 mm) crush lesions made by microforceps in mice and rats often recover very well in weeks (Figure 1D; Brushart, 2011). Such short-length crush lesions almost never occur in large mammals like humans (Green and Wolfe, 2011).

Third, PEG-fused allografts are not in a privileged environment but are not rejected despite not being tissue matched nor immune suppressed, even if the donor is not of the same stain (or species; unpublished data) as the host. PNI allografts are indeed very allogenic, as documented by their rapid rejection in Negative Control protocols in which all solutions are used except PEG or in which PEG is used but microsutures do not closely appose cut ends. Although the mechanism is not yet known, one working hypothesis is that rapid restoration of axonal transport through a fusion site may allow the host to introduce its MHC proteins into donor axons in the grafted segment, thus disguising the graft as “self”, thereby escaping immune surveillance and targeting. Regardless of mechanism, the lack of rejection of PEG-fused allografts is very different from allograft transplant repair of other tissues (Murphy and Weaver, 2016). That is, the 50% PEG solution used in a PEG-fusion protocol may have some neuroprotective effects but PEG-fusion is a very different functional use of PEG compared to its use in PEG-hydrogels as a neuroprotective agent (Kwon et al., 2009)

Fourth, PEG-fusion works by non-specifically joining open cut axonal ends (Riley et al., 2015; Bittner et al., 2016, 2017; Ghergherehchi et al., 2016). For allografts, this non-specificity includes different numbers of axons in donor and host nerve segments (Riley et al., 2015; Bittner et al., 2016). Such PEG-fused axons immediately restore action potential conduction across the lesion sites, as demonstrated by CAPs, CMAPs and muscle twitches (Figure 1A, B). Good recovery of behaviors usually occurs after several weeks (Figure 1D), but before any axons regenerating by outgrowth have reached muscle masses that remain innervated. These muscle masses do not atrophy because PEG-fused axons do not undergo Wallerian degeneration (Table 1). Outcomes from PEG-fusion repair of allografts are superior to PEG-fusion repair of single transections, almost certainly because the allograft is sized to be longer than the ablated segment after all cut ends are carefully trimmed, thereby eliminating any deleterious strain/tension of any host or donor axons (Riley et al., 2015). The behavioral recovery after PEG-fusion of a single transection or an ablation/allograft insertion presumably occurs by activating peripheral and CNS plasticities to a much greater extent than most neuroscientists currently believe to be possible (Riley et al., 2015; Bittner et al., 2016, 2017). As part of this conundrum/confusion, we note that PEG-fusion does not prevent regeneration by outgrowth, presumably from axons that were not successfully PEG-fused (Table 1; Bittner et al., 2016). However, such outgrowth adds little to the recovery already obtained by surviving PEG-fused axons in allografts after segment ablation of a major peripheral nerve (Figure 1D).

As one specific example of errors in interpretation of the PEG-fusion mechanism and/or results, a recent publications (Robinson and Madison, 2016) attempted “to assess motor neuron regeneration accuracy” after PEG-fusion. The authors concluded that PEG-fusion led to inaccuracy in regeneration by outgrowth and hence would probably fail as a clinical technique. However, these researchers did not perform a positive control (CAP conduction across the site of PEG-fusion) to demonstrate that they produced PEG-fusion at the time of their original surgery or a positive control behavioral test, such as the SFI, to demonstrate that they maintained successful PEG-fusion at any time postoperatively, especially when they attempted to assess the innervation accuracy of axons.

More importantly, even if one assumes that Robinson and Madison (2016) did produce successful PEG-fusion in the absence of evidence, the experimental protocol employed to assess the specificity of axons regenerating by outgrowth cannot distinguish between axons regenerating by outgrowth versus those that were PEG-fused immediately after injury to produce immediate reinnervation and have been maintained. Logically, one cannot label a nerve that contains both newly regenerated axons as well as maintained PEG-fused axons and then attribute all the results to axons regenerating by outgrowth, as the authors concluded (Bittner et al., 2017). They also failed to consider a set of relevant papers (Riley et al., 2015; Bittner et al., 2016) describing PEG-fusion recovery after allograft repair of ablated segments, at which time no regenerating axons have reached the denervated muscles, but instead reinnervation is solely due to by surviving PEG-fused axons. To date there is no study that has published data that validly addresses reinnervation by PEG-fusion versus regeneration by outgrowth from surviving proximal stumps.

PEG-fusion technologies could produce a paradigm shift in current Neuroscience dogma that asserts that: 1) distal stumps of severed axons undergo obligate degeneration within days; 2) reinnervation can only occur by slowly growing regenerating processes from severed proximal stumps that need appropriately reinnervate denervated target tissues (that have often atrophied); and 3) allo-transplanted neuronal tissue is always rapidly rejected in unprotected immune environments.

In contrast, PEG-fusion results show that: 1) distal stumps of severed axons survive indefinitely, 2) reinnervation can occur within seconds to minutes by connecting axons in proximal and distal stumps to appropriately or inappropriately reinnervate denervated target tissues; 3) target tissues to not undergo atrophy; 4) remarkable behavioral restoration is obtained due to inappropriate connections that must be subject to substantial peripheral and/or CNS plasticities that support functional recovery; 5) PEG-fused transplanted allogenic neuronal tissue is most unexpectedly not rejected despite no tissue matching or immune suppression; and 6) PEG fusion works very similarly in humans in early case studies, as it does in rats.

All these results suggest that PEG-fusion technologies have the potential to produce a paradigm shift in clinical treatment of PNS nerve injuries.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Financial support: None.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bittner GD, Sengelaub DR, Trevino RC, Ghergherehchi CL, Mikesh M. Robinson and madison have published no data on whether polyethylene glycol fusion repair prevents reinnervation accuracy in rat peripheral nerve. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95:863–866. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bittner GD, Sengelaub DR, Trevino RC, Peduzzi JD, Mikesh M, Ghergherehchi CL, Schallert T, Thayer WP. The curious ability of polyethylene glycol fusion technologies to restore lost behaviors after nerve severance. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94:207–230. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bittner GD, Keating CP, Kane JR, Britt JM, Spaeth CS, Fan JD, Zuzek A, Wilcott RW, Thayer WP, Winograd JM, Gonzalez-Lima F, Schallert T. Rapid, effective, and long-lasting behavioral recovery produced by microsutures, methylene blue, and polyethylene glycol after completely cutting rat sciatic nerves. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:967–980. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brushart TM. Nerve Repair. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghergherehchi CL, Bittner GD, Hastings RL, Mikesh M, Riley DC, Trevino RC, Schallert T, Thayer WP, Sunkesula SR, Ha TA, Munoz N, Pyarali M, Bansal A, Poon AD, Mazal AT, Smith TA, Wong NS, Dunne PJ. Effects of extracellular calcium and surgical techniques on restoration of axonal continuity by polyethylene glycol fusion following complete cut or crush severance of rat sciatic nerves. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94:231–245. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green DP, Wolfe SW. Green's Operative Hand Surgery. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM, Siegelbaum SA, Hudspeth AJ. Principles of Neural Science. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon BK, Roy J, Lee JH, Okon E, Zhang H, Marx JC, Kindy MS. Magnesium chloride in a polyethylene glycol formulation as a neuroprotective therapy for acute spinal cord injury: preclinical refinement and optimization. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1379–1393. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy K, Weaver C. Janeway's Immunobiology. New York, NY: Garland Science/Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riley DC, Bittner GD, Mikesh M, Cardwell NL, Pollins AC, Ghergherehchi CL, Bhupanapadu Sunkesula SR, Ha TN, Hall BT, Poon AD, Pyarali M, Boyer RB, Mazal AT, Munoz N, Trevino RC, Schallert T, Thayer WP. Polyethylene glycol-fused allografts produce rapid behavioral recovery after ablation of sciatic nerve segments. J Neurosci Res. 2015;93:572–583. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson GA, Madison RD. Polyethylene glycol fusion repair prevents reinnervation accuracy in rat peripheral nerve. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94:636–644. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spaeth CS, Robison T, Fan JD, Bittner GD. Cellular mechanisms of plasmalemmal sealing and axonal repair by polyethylene glycol and methylene blue. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:955–966. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]