Abstract

Background

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare genetic disease causing unpredictable and potentially life-threatening subcutaneous and submucosal edematous attacks. Cinryze® (Shire ViroPharma Inc., Lexington, MA, USA), a nanofiltered C1 inhibitor (C1-INH), is approved in Europe for the treatment, preprocedure prevention, and routine prophylaxis of HAE attacks, and for the routine prophylaxis of attacks in the USA. This phase 3 study assessed the safety and efficacy of 2 C1-INH doses in preventing attacks in children aged 6–11 years.

Methods

A randomized single-blind crossover study was initiated in March 2014. Results for the first 6 patients completing the study are reported here. After a 12-week qualifying observation period, patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 C1-INH doses, 500 or 1,000 U, every 3–4 days for 12 weeks and crossed over to the alternative dose for a second 12-week period. The primary efficacy endpoint was the number of angioedema attacks per month.

Results

Six females with HAE type I and a median age of 10.5 years received 2 doses of C1-INH (500 and 1,000 U). The mean (SD) difference in the number of monthly angioedema attacks between the baseline observation period and the treatment period was −1.89 (1.31) with 500 U and −1.89 (1.11) with 1,000 U. During the treatment periods, cumulative attack severity, cumulative daily severity, and the number of attacks needing acute treatment were lower. No serious adverse events or study drug discontinuations occurred.

Conclusions

Interim findings from this study indicate that routine prevention with intravenous administration of C1-INH is efficacious, safe, and well tolerated in children ≥6 years of age.

Keywords: Cinryze®, Hereditary angioedema, Attack, Prevention, Pediatric patients, Efficacy, Safety

Introduction

Hereditary angioedema (HAE), a rare disease with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 50,000 [1], is characterized by episodic swelling of the skin, abdomen, and larynx [2, 3]. HAE types I and II are identified by low total levels and nonfunctionality of the C1 inhibitor (C1-INH), respectively, accounting for approximately 85 and 15% of cases [4]. Untreated HAE attacks can last for 2–5 days [5]. The clinical presentation of HAE, including age of symptom onset, anatomical location, frequency, and severity [6, 7, 8], are diverse, and about 50% of patients can experience potentially fatal laryngeal attacks [9, 10]. Examples of attack triggers are stress, hormonal changes, surgical or dental procedures, infection, or hormonal therapy for women such as oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy [11, 12, 13, 14].

To minimize disease burden and improve quality of life [15, 16], prophylaxis is recommended. Three commercially available human plasma-derived C1-INHs [17, 18, 19] for HAE are available with small differences in purity, antigen-activity ratio, and specific activity [20]. However, Cinryze® (Shire ViroPharma Inc., Lexington, MA, USA), a nanofiltered human plasma-derived C1-INH, is the only approved C1-INH for routine prophylaxis in adolescents and adults in the USA, and in pediatric patients (≥6 years of age) with severe and recurrent attacks, adolescents, and adults in the EU [19]. Cinryze is also approved in the EU for the on-demand treatment of acute attacks and for preprocedure prevention of attacks in patients (≥2 years of age). It is administered intravenously to patients as a fixed dose rather than a body weight-adjusted dose of 1,000 U every 3–4 days in adolescents and adults and 500 U or 1,000 U if needed in pediatric patients. Previous studies including 2 placebo-controlled and 2 open-label extension studies involving 46 patients indicated that C1-INH is safe and efficacious in this group [21].

The objective of this ongoing phase 3 study is to assess the safety and relative efficacy of 2 different C1-INH doses in preventing HAE attacks in children aged 6–11 years who have recurrent attacks. Herein we report the interim results for the first 6 patients who completed the study.

Patients and Methods

This is an ongoing randomized phase 3 single-blind crossover study involving 4 US sites and 3 EU sites (NCT02052141). Data for this interim analysis were collected between March 2014 and April 2015. Parents or legal guardians provided written informed consent, and patients assented to participate in this study. The study protocol, informed consent, and subject recruitment information were approved by the ethics committees before study initiation. This study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and other applicable local ethical and legal requirements. Patient selection was based on the following: age ≥6 and <12 years, a confirmed HAE type I or II diagnosis, a functional C1-INH level that was <50% of normal levels, and a monthly average of ≥1.0 attacks classified as moderate, severe, or needing acute treatment in the 3-month period before screening. The requirement for monthly attack frequency was ≥2.0 in Germany, and patients were required to be ≥25 kg in weight. Patients with a history of hypercoagulability, allergic reaction to C1-INH products, or an acquired angioedema diagnosis were excluded.

Following screening, there was a 12-week baseline observation period to monitor patients' HAE attacks. Patients who experienced ≥1.0 monthly attacks classified as moderate or severe or that necessitated acute treatment during the baseline observation period (≥2.0 monthly attacks in Germany) were then randomly assigned to 1 of 2 intravenous C1-INH doses, 500 or 1,000 U, administered every 3–4 days for 12 weeks. Patients switched to the alternative dose for a second 12-week period. Patients were not randomized if they had an active infectious illness or a fever within 24 h, or signs and/or symptoms of an angioedema attack within 2 days. Patients and their parents or caregivers were blinded to the treatment sequence.

Parents or caregivers used electronic study diaries to record study information, and all patients were followed up 1 week and 1 month after treatment initiation. Attack severity was rated as mild, moderate, or severe, corresponding to severity scores of 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Adverse events were recorded. Physical examinations, vital sign measurement, clinical laboratory tests, and testing for anti-C1-INH antibodies were also performed.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the number of attacks per month in a 12-week treatment period. Secondary efficacy endpoints, also calculated for each patient in a 12-week period, were cumulative attack severity (the sum of the maximum symptom severity score recorded for each attack), cumulative daily severity (the sum of the maximum severity scores recorded for each day of symptoms), and the number of attacks requiring acute treatment. These values were normalized for the number of days a patient participated in a given period and expressed as a monthly frequency.

Results

Six female patients with HAE type I and a median (range) age of 10.5 (7–11) years have completed the study (Table 1). In the 3 months before screening, patients experienced a mean (SD) of 4.2 (1.2) attacks per month, and all patients reported ≥1 angioedema attack affecting the gastrointestinal tract or abdomen. After the 12-week baseline observation period, 2 patients received 500 U C1-INH (for 12 weeks) followed by 1,000 U C1-INH (for 12 weeks), and 4 patients received these treatment doses in the opposite sequence. Each patient received 23–24 injections of 500 U C1-INH and 22–24 injections of 1,000 U C1-INH. Four patients (67%) had ≥1 concomitant medications; however, only 2 patients (33%) received concomitant medications to manage HAE attacks and its associated symptoms. One patient received concomitant treatment with a single intravenous C1-INH dose (1,000 U) for a mild upper airway attack. Another patient received Baralgina (with fenpiverinium bromide, metamizole sodium, and pitofenone hydrochloride as major components) to manage a severe gastrointestinal attack.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, baseline characteristics, and characteristics of attacks that occurred up to 3 months before patient screening (n = 6)

| Overall characteristics | |

| Age, years | 10.5 (7.0 – 11.0) |

| Female, n | 6 (100) |

| Race, n | |

| White | 5 (83.3) |

| Mixed: black, white | 1 (16.7) |

| Weight, kg | 32.0 (23.2 – 47.1) |

| Height, cm | 147.5 (118 – 159) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 16.8 (13.1 – 20.0) |

| HAE type I, n | 6 (100) |

| Attacks that occurred up to 3 months before screening | |

| Number of attacks | 4 (3 – 6) |

| Locations affected by attacks, n | |

| Upper airway | 1 (16.7) |

| Gastrointestinal or abdominal region | 6 (100) |

| Genitourinary | 1 (16.7) |

| Facial | 3 (50.0) |

| Extremity or peripheral | 5 (83.3) |

| Average severity of attacks, n | |

| Mild | 0 |

| Moderate | 5 (83.3) |

| Severe | 1 (16.7) |

| Average duration of attack, days | 1.5 (1 – 3) |

| Patients needing acute treatment for HAE attack, n | 2 (33.3) |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range), as appropriate. HAE, hereditary angioedema.

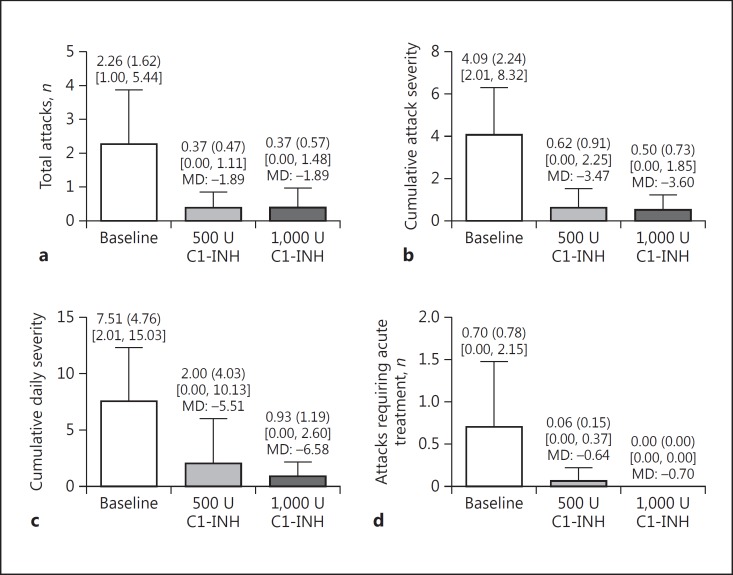

The mean (SD) number of attacks after the observation period was 2.26 (1.62) attacks per month. The mean (SD) difference (normalized per month) in the number of attacks between the observation period and the treatment period was −1.89 (1.31) with 500 U and −1.89 (1.11) with 1,000 U (Fig. 1a), which is a reduction of −84.8 and −88.1%, respectively. During both treatment periods, cumulative attack severity, cumulative daily severity, and the number of attacks needing acute treatment were also lower (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Primary and secondary endpoints (numbers are normalized per month). a Total number of HAE attacks. b Cumulative attack severity (the sum of the maximum symptom severity score recorded for each attack. c Cumulative daily severity (the sum of the maximum severity scores recorded for each day of symptoms). d Number of attacks needing acute treatment. Mean (SD) values are shown at the top of each bar. Maximum and minimum values are shown in square brackets. The mean differences (MD) between the baseline observation period and the treatment period with a nanofiltered C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) are also shown.

Five patients experienced a total of 55 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs): 25 TEAEs in 4 patients while receiving 500 U C1-INH and 30 TEAEs in 5 patients while receiving 1,000 U C1-INH. The adverse event profiles for both doses were comparable. No serious adverse events, thrombotic events, thromboembolic events, or study drug discontinuations occurred. One patient had 2 severe angioedema attacks during treatment with 500 U C1-INH. Adverse events of fatigue and irritability in 2 patients each were related to the study drug (Table 2). No patients reported a TEAE during infusion of either C1-INH dose, and the majority of TEAEs (HAE attack, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, fatigue, and irritability) occurred within 24 h after administration. In addition, all patients tested negative for anti-C1-INH antibodies, and no clinically relevant abnormalities were found in clinical laboratory tests or vital signs.

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events

| Patients who experienced at least 1 event of that type |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 weeks 500 U C1-INH (n = 6) |

12 weeks 1,000 U C1-INH (n = 6) |

total (n = 6) |

|

| Type of TEAE (within 24 h after administration) | |||

| Any type | 4 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) |

| HAE attack | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 4 (66.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Fatigue | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Irritability | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| TEAE related to the study drug | |||

| Any type | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Fatigue | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Irritability | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| TEAE by maximum severity | |||

| Mild | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| Moderate | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Severe | 1 (16.7)a | 0 | 1 (16.7)a |

| TEAE during study drug administration | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Any serious event | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAE leading to study drug discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data are presented as n (%). HAE, hereditary angioedema; TEAEs, treatment-emergent adverse events.

One patient reported 2 severe TEAEs that were HAE attacks during treatment with 500 U of a nanofiltered C1 inhibitor (C1-INH).

Discussion

A study of Danish patients with HAE found that the mean annual attack rate, without prophylaxis, was 17 per year, with broad variation between patients [22]. This interim analysis of an ongoing phase 3 study showed that intravenously administered C1-INH (500 or 1,000 U) was safe and well tolerated in children aged 7–11 years with HAE. The same formulation of C1-INH (1,000 U) was previously evaluated in a placebo-controlled, crossover study of mostly adult patients with a history of ≥2 monthly attacks [23]. The number of attacks per 12-week period was significantly reduced from 12.7 with placebo to 6.3 with C1-INH. The severity and number of attacks needing open-label rescue therapy were also reduced. An open-label 2.6-year extension study in patients with a mean (SD) age of 36.5 (16.5) years showed that C1-INH prophylaxis reduced the median number of monthly attacks by 93.7% (3.00–0.19) [24]. A post hoc analysis of data from 4 prospective clinical trials was performed to evaluate the efficacy of C1-INH (1,000 U) for acute treatment and prophylaxis in a pediatric subgroup [21]. This post hoc analysis showed that in the placebo-controlled trial, 4 patients (9–17 years of age) had their number of HAE attacks almost halved from 13.0 with placebo to 7.0 with C1-INH prophylaxis. In addition, 23 patients aged 2–17 years in the open-label extension study [21] had a reduction in their median (range) monthly attacks from 3.0 (0.5–28.0) before enrollment to 0.39 (0–3.36) after prophylaxis. However, this was a post hoc analysis rather than a clinical trial in children with HAE. The interim analysis described here, however, shows a similar reduction in the monthly number of attacks from a mean (SD) of 2.262 (1.622) at baseline to 0.372 (0.470) with 500 U C1-INH and 0.372 (0.573) with 1,000 U C1-INH. This is an 84% reduction in the number of attacks relative to baseline. Moreover, the attacks that occurred were generally less severe and fewer required rescue medication.

C1-INH is used as prophylaxis because it acts on the complement and contact plasma cascades, thereby reducing bradykinin release (the main pathologic mechanism in HAE) [25]. At the end of the study, 4 patients (66.7%) were attack free after prophylaxis at either dose. Previous studies have also shown that patients still experience HAE attacks while on C1-INH prophylaxis. In the placebo-controlled phase 3 study [23], 18% of 22 patients were attack free after prophylaxis [26]. In the open-label extension study [24], 35% of 146 patients were attack free following prophylaxis. Although routine prophylaxis with C1-INH reduces attack severity and frequency, it does not completely prevent breakthrough attacks. Since administered C1-INH doses are unable to return functional C1-INH to normal levels in all patients, it is likely that individualization of the dose or administration frequency will be needed to achieve optimal responses in some patients [23]. In support of this, another study found that escalating the C1-INH dose to 2,500 U every 3 or 4 days for those who are not responsive to 1,000 U is well tolerated [27]. In addition, C1-INH was shown in a previous study to have a positive impact on the quality of life of patients [28].

Our study indicates that regular C1-INH infusions provided effective prophylaxis in this group of pediatric patients with a considerable pretreatment disease burden. The target sample size in this study is small but appropriate given the rarity of HAE and the specific age group. Although this is an interim analysis, the results support previous clinical studies [21] indicating that C1-INH may have a beneficial, prophylactic role in HAE management in children.

Disclosure Statement

James Hao and Jennifer Schranz are full-time employees of Shire (Lexington, MA, USA). Arthur Van Leerberghe is a full-time employee of Shire (Brussels, Belgium). Dumitru Moldovan received research funding and travel grants from CSL Behring, Pharming Technologies, and Shire HGT, unrestricted educational grants from CSL Behring, Pharming Technologies, Shire HGT, and Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, and served as consultant for Pharming Technologies and Swedish Orphan Biovitrum. Emel Aygören-Pürsün and Inmaculada Martinez-Saguer received honoraria, research funding, and/or travel grants from Biocryst, CSL Behring, Pharming Technologies, and Shire and/or served as a consultant for these companies. Daniel Soteres is a speaker and has participated in advisory boards for Shire. Kraig W. Jacobson has participated in clinical trials for Shire. Jim Christensen has nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the sponsor, Shire ViroPharma Inc., Lexington, MA, USA. Under the direction of the authors, Sally Hassan, PhD, of Excel Scientific Solutions provided writing assistance for this publication. Excel Scientific Solutions also provided editorial assistance in formatting, proofreading, copyediting, and fact checking. James Hao and Irmgard Andresen from Shire HGT also reviewed and edited the manuscript for scientific accuracy. Shire HGT provided funding to Excel Scientific Solutions for support in writing and editing this manuscript. Although employees of the sponsor were involved in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation, and fact checking of information, the content of this manuscript, the interpretation of its data, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication were independently made by the authors. These data were presented at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Congress, 2015, in Vienna, Austria.

References

- 1.Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. New Engl J Med. 2008;359:1027–1036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0803977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams AH, Craig TJ. Perioperative management for patients with hereditary angioedema. Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 2015;6:50–55. doi: 10.2500/ar.2015.6.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt J. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med. 2006;119:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston DT. Diagnosis and management of hereditary angioedema. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gompels MM, Lock RJ, Abinun M, Bethune CA, Davies G, Grattan C, Fay AC, Longhurst HJ, Morrison L, Price A, Price M, Watters D. C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus document. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;139:379–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bork K. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor activity including hereditary angioedema with coagulation factor XII gene mutations. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26:709–724. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aygören-Pürsün E, Bygum A, Beusterien K, Hautamaki E, Sisic Z, Wait S, Boysen HB, Caballero T. Socioeconomic burden of hereditary angioedema: results from the hereditary angioedema burden of illness study in Europe. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:99. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caballero T, Aygören-Pürsün E, Bygum A, Beusterien K, Hautamaki E, Sisic Z, Wait S, Boysen HB. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: results from the Burden of Illness Study in Europe. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35:47–53. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bork K, Ressel N. Sudden upper airway obstruction in patients with hereditary angioedema. Transfus Apher Sci. 2003;29:235–238. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bork K, Siedlecki K, Bosch S, Schopf RE, Kreuz W. Asphyxiation by laryngeal edema in patients with hereditary angioedema. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:349–354. doi: 10.4065/75.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bork K, Hardt J, Staubach-Renz P, Witzke G. Risk of laryngeal edema and facial swellings after tooth extraction in patients with hereditary angioedema with and without prophylaxis with C1 inhibitor concentrate: a retrospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morcavallo PS, Leonida A, Rossi G, Mingardi M, Martini M, Monguzzi R, Carini F, Baldoni M. Hereditary angioedema in oral surgery: overview of the clinical picture and report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2307–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zotter Z, Csuka D, Szabo E, Czaller I, Nebenfuhrer Z, Temesszentandrasi G, Fust G, Varga L, Farkas H. The influence of trigger factors on hereditary angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouillet L. Hereditary angioedema in women. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang SW. Results of an on-line survey of patients with hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2004;25:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lumry WR, Castaldo AJ, Vernon MK, Blaustein MB, Wilson DA, Horn PT. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: impact on health-related quality of life, productivity, and depression. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:407–414. doi: 10.2500/aap.2010.31.3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CSL Behring Berinert® (C1 Esterase Inhibitor [Human]): Full Prescribing Information. Marburg, Germany, CSL Behring GmbH, September 2016 http://labeling.cslbehring.com/PI/US/Berinert/EN/Berinert-Prescribing-Information.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

- 18.Sanquin: Cetor®: Summary of Product Characteristics Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Sanquin, 2010. https://www.sanquin.nl/repository/documenten/en/prod-en-dienst/plasmaproducten/139660/Summary_of_ Product_Characteristics.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

- 19.European Medicines Agency Cinryze 500 Units Powder And Solvent For Solutions For Injection: Summary of Product Characteristics London, European Medicines Agency, December 2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/001207/WC500108895.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

- 20.Feussner A, Kalina U, Hofmann P, Machnig T, Henkel G. Biochemical comparison of four commercially available C1 esterase inhibitor concentrates for treatment of hereditary angioedema. Transfusion. 2014;54:2566–2573. doi: 10.1111/trf.12678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lumry W, Manning ME, Hurewitz DS, Davis-Lorton M, Fitts D, Kalfus IN, Uknis ME. Nanofiltered C1-esterase inhibitor for the acute management and prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks due to C1-inhibitor deficiency in children. J Pediatr. 2013;162:1017–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.11.030. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bygum A. Hereditary angioedema - consequences of a new treatment paradigm in Denmark. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:436–441. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, Jacobs J, Lumry W, Baker J, Craig T, Grant JA, Hurewitz D, Bielory L, Cartwright WE, Koleilat M, Ryan W, Schaefer O, Manning M, Patel P, Bernstein JA, Friedman RA, Wilkinson R, Tanner D, Kohler G, Gunther G, Levy R, McClellan J, Redhead J, Guss D, Heyman E, Blumenstein BA, Kalfus I, Frank MM. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. New Engl J Med. 2010;363:513–522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuraw BL, Kalfus I. Safety and efficacy of prophylactic nanofiltered C1-inhibitor in hereditary angioedema. Am J Med. 2012;125:938. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.02.020. e931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gower RG, Busse PJ, Aygören-Pürsün E, Barakat AJ, Caballero T, Davis-Lorton M, Farkas H, Hurewitz DS, Jacobs JS, Johnston DT, Lumry W, Maurer M. Hereditary angioedema caused by C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency: a literature-based analysis and clinical commentary on prophylaxis treatment strategies. World Allergy Organ J. 2011;4:S9–S21. doi: 10.1097/1939-4551-4-S2-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shire: Cinryze® (C1 Esterase Inhibitor [Human]). Full Prescribing Information Lexington, Shire ViroPharma Inc., December 2016. http://pi.shirecontent.com/PI/PDFs/Cinryze_USA_ENG.pdf (accessed June 23, 2017).

- 27.Bernstein JA, Manning ME, Li H, White MV, Baker J, Lumry WR, Davis-Lorton MA, Jacobson KW, Gower RG, Broom C, Fitts D, Schranz J. Escalating doses of C1 esterase inhibitor (Cinryze) for prophylaxis in patients with hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lumry WR, Miller DP, Newcomer S, Fitts D, Dayno J. Quality of life in patients with hereditary angioedema receiving therapy for routine prevention of attacks. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35:371–376. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]