Abstract

Aims

Regenerative therapies have evolved as a promising new option in the treatment of post-infarction heart failure. A major limitation of intracoronary application of autologous bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) is that homing of the applied cells is profoundly reduced in patients with post-infarction heart failure compared with patients with acute myocardial infarction. However, early pilot and also randomized controlled trials have demonstrated significant improvements in overall cardiac function. The aim of the present analysis was to quantify a potential mortality risk reduction and reduced hospitalization in order to provide data for a prospective outcome trial.

Methods and results

The results of an ongoing single-centre registry including 297 post-infarction heart failure patients suggest that repeated intracoronary application of autologous bone marrow-derived cells is associated with a significant better 2-year survival compared with a single BM-MNC application (2-year survival 93.6 vs. 84.0%, P = 0.03). Likewise, mortality is significantly lower at 2-year follow-up compared with the mortality estimated by the use of the Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM) in patients receiving repeated BM-MNC application (observed mortality 6.4%, predicted mortality 16.2%, P = 0.02). Although the trend persisted at 3-year follow-up, the mortality reduction was no longer statistically significant between single and repeated treatment (mortality 21.9 vs. 13.7%, P = 0.06).

Conclusion

Repeated intracoronary administration of BM-MNC appears to be associated with improved clinical outcome compared with single treatment at 2 years. This registry provides the rationale for the design of the multicentre randomized, controlled, open-label REPEAT trial, which prospectively compares the effects of single vs. repeated intracoronary application of autologous BM-MNC on total and SHFM-predicted mortality in patients with chronic post-infarction heart failure.

Keywords: Chronic heart failure, Ischaemic cardiomyopathy, Cell therapy, Outcome trial

See page 1667 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv596)

Introduction

The prevalence of chronic heart failure continues to increase.1 One major cause for chronic heart failure is coronary artery disease with one or multiple previous myocardial infarctions, which, due to recent advances in therapies, more and more patients survive.2 However, as a consequence, more patients develop post-infarction heart failure due to adverse left ventricular remodelling. The presence of chronic post-infarction heart failure is associated with massively reduced life expectancy and quality of life. For example, patients suffering from chronic post-infarction heart failure require frequent hospitalizations due to cardiac decompensation. In fact, from ∼15 millions heart failure patients in Europe, 1.5 millions require at least 1 hospitalization for heart failure per year, which also causes tremendous expenses of 2% of the overall healthcare costs.

Cell therapy offers the attractive option of improving left ventricular function and reducing adverse left ventricular remodelling.3 Mechanistically, it is currently assumed that the beneficial effects of autologous bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (BM-MNC) are mediated by the release of paracrine factors from the retained cells which enhance endogenous repair mechanisms and improve the function of the coronary microcirculation (for review see Ref. 4).

So far, >3000 patients with cardiovascular diseases were treated with adult progenitor cells worldwide, and no serious adverse side effects were reported. In recent meta-analyses, treatment with bone marrow-derived progenitor cells was associated with a significantly reduced mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI).5,6 However, limited data are available about effects of intracoronary infusion of autologous BM-MNC in patients with old, at least 3 months old myocardial infarction and post-infarction heart failure. Our own randomized, cross-over trial showed a significant, albeit modest improvement by absolute 3% in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at 3 months after intracoronary infusion of bone marrow-derived cells, but no change in the control group.7 In a smaller, non-randomized Danish trial, 32 patients were treated with two repeated intracoronary infusion of BM-MNC. The symptom status of these patients was significantly improved at 12 months, and there was a tendency towards fewer hospitalizations for heart failure compared with an observational period of 12 months prior to participation in the trial.8 However, there are no long-term mortality data in large patient populations with post-infarction heart failure, but such studies are required to ultimately assess the value of this treatment modality with a view to it becoming standard clinical practice. For this purpose, we assessed the clinical outcome of 297 consecutive patients receiving intracoronary administration of BM-MNC for chronic post-infarction heart failure between 2002 and 2008 at the Goethe University Frankfurt, with the aim to generate the basis for a randomized trial. Observed mortality was compared with the Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM)-predicted mortality, which was shown to be an accurate long-term estimate, including contemporary pharmacological and device therapies.9

Methods

Patients

The registry cohort comprises all 297 consecutive patients included into an ongoing registry to assess the effects of intracoronary administration of BM-MNC for treatment of chronic post-ischaemic heart failure due to an at least 3 months old myocardial infarction at a single centre, the Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, between January 2002 and December 2008. Patients were eligible for inclusion into the study if they suffered from stable chronic heart failure symptoms NYHA ≥II, had a previous, successfully revascularized myocardial infarction at least 3 months before BM-MNC administration and had a well-demarcated region of left ventricular dysfunction on echocardiography. Exclusion criteria for intracoronary cell treatment were the presence of acutely decompensated heart failure with NYHA class IV, an acute ischaemic event within 3 months prior to inclusion into the registry, a history of severe chronic diseases, documented cancer within the preceding 5 years, or unwillingness to participate.

After establishing the safety of intracoronary BM-MNC administration in 54 patients, from the beginning of 2004, all following patients were invited to receive repeated BM-MNC administration at their clinical follow-up appointment at 3–6 months after the first treatment, in order to assess a potential additive effect of repetitive cell administration. Thus, 111 of the 297 patients received an additional BM-MNC administration at 3–6 months after the initial treatment. The main reason for not repeating BM-MNC therapy was unwillingness to stay in hospital for the second BM-MNC treatment, or long-distance travelling.

The ethics review board of the Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, approved the protocol, the study is registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00962364), and all patients gave written informed consent to participate in this prospective registry. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Preparation and administration of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells

Bone marrow aspirate (50 mL) was obtained from the iliac crest under local anaesthesia in the morning of the cell administration day (repeated treatment patients received a second bone marrow aspiration and de novo cell isolation procedure at the time of the second cell treatment). BM-MNC were then isolated by Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation, as previously reported.7,10 A mean of 190 ± 110 × 106 cells were available for the intracoronary infusion procedure after processing. For cell administration, arterial puncture was followed by the administration of 5000–7500 U of heparin. BM-MNC were infused into the vessel supplying the most dyskinetic left ventricular area by means of the stop-flow technique with an over-the-wire balloon catheter, as previously described.10 In all but one patient, the target vessel for cell therapy was a native coronary artery.

Follow-up

Clinical data, medication, and laboratory data were prospectively collected by study nurses. Follow-up visits were scheduled at 3 months after each cell application, and then at 12 months after the first cell application, and were performed by physicians, whereas follow-up telephone calls were performed by study nurses at 24, 36, and 48 months.

Mortality and mode of death were adjudicated by means of reviewing medical records by the study physicians. Mode of death was classified as sudden death (unexpected death in a clinically stable patient, typically within 1 h of symptom onset, from documented or presumed cardiac arrhythmia, and without a clear non-cardiovascular cause), pump failure (progressively reduced cardiac output and failure of organ perfusion), non-cardiac death or not classifiable. Implantation of left ventricular assist devices or cardiac transplantations (n = 2) was categorized as death due to pump failure at the time of surgery. All events were prospectively ascertained and classified by physicians unaware of the patients' SHFM scores.

Calculation of the Seattle Heart Failure Model score

The SHFM is a validated risk prediction model based on routinely collected clinical variables, including age, gender, aetiology of cardiomyopathy (ischaemic origin), heart rate, systolic blood pressure, ejection fraction, medication (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, aldosterone blocker, beta-blocker, statins, as well as diuretic type and daily dose, and allopurinol), and laboratory values (serum sodium, total cholesterol, haemoglobin, percent lymphocytes, uric acid).9 In addition, the presence of any implantable device [pacemaker, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), cardiac resynchronization therapy] is included into the calculation of both, the SHFM Score as well as the SHFM-predicted mortality. However, NT-proBNP or BNP values are not included into the model.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range), unless otherwise noted. Analysis-of-variance testing was used for comparison of continuous variables between groups. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test.

For survival analysis within the individual group, Kaplan–Meier analysis was used, including the standard error (SE) with the Greenwood formula. Furthermore, confidence intervals for survival rates were calculated using the log–log transformation. For comparison of survival rates (Figure 2), a multivariable Cox proportional-hazards regression model was used, taking into account the covariates SHFM score, and the number of BM-MNC treatments. 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratio (HR) were also calculated. Estimated survival curves were computed after fitting the Cox regression model. Landmark analyses were performed with a cut-off of 90 days in the single treatment group, which was the earliest time for repeated treatment, and with the day of repeated cell treatment in the repeated treatment group.

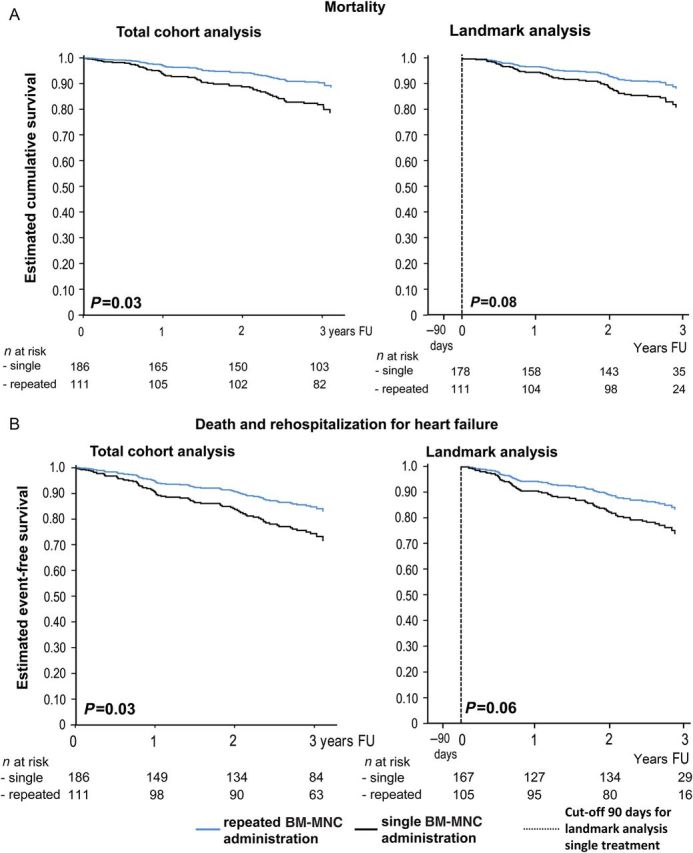

Figure 2.

(A) Cox regression analysis for total mortality, adjusted for the Seattle Heart Failure Model score, in the entire study cohort (left) and the landmark analysis (right). Note that the reference time (90 days) for the landmark analysis is marked by a vertical line. (B) Cox regression analysis for the combined endpoint mortality and rehospitalization for heart failure, adjusted for the Seattle Heart Failure Model score, in the entire study cohort (left) and the landmark analysis (right). The reference time (90 days) for the landmark analysis is marked by a vertical line.

The calculation of estimated survival by the SHFM score is based on a parametric (exponential) survival model.9 Therefore, a likelihood ratio test can be defined and calculated for comparison between estimated mortality according to the SHFM score and the pre-specified parameter in the survival model and observed mortality. Thereby, we compared the pre-specified coefficient of exp(SHFM) with a maximum likelihood estimator for the coefficient of exp(SHFM) from the new data in a comparable exponential model. The maximum likelihood estimator of the coefficient can be calculated as number of cases divided by the sum of observation time ti multiplied with exp(SHFM) of the ith observed individual patient.

Statistical significance was assumed for P values of <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 16.0), SAS software (version 9.4), and the comparison between estimated and observed mortality was performed with R, a language and environment for statistical computing (version 3.0.2).

Results

During 3-year follow-up, 58 patients died and 10 patients were lost to follow-up (3.3%). In detail, four patients were lost at 1-year follow-up and nine patients were lost at 2-year follow-up. The baseline characteristics of the 297 patients are summarized in Table 1, according to single or repeated treatment. The most recent myocardial infarction had occurred at a mean time of 88.5 months (median = 60 months) prior to intracoronary BM-MNC administration. All patients received optimal pharmacological treatment. Clinical characteristics did not differ at the time of first or second treatment in the repeated treatment group except for NYHA class, which was significantly improved at the time of repeated treatment (see Supplementary material online, Table S1). Characteristics of the applied BM-MNC were also comparable between the two treatment groups (Table 2). Total time at risk was 833 patient-years. Of note, baseline characteristics and SHFM score of the 10 patients lost to follow-up at 3 years did not significantly differ from the overall patient cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort

| Single Tx (n = 186) Median (IQR) | Repeated Tx (n = 111) Median (IQR) | P value (single vs. repeated) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62 (55–68) | 65 (57–72) | 0.004 |

| Sex (male/female; n) | 167/19 | 95/16 | 0.35 |

| Weight (kg) | 81 (72–90) | 78 (71–88) | 0.13 |

| SHFM score | 0.3 (−0.1–0.8) | 0.4 (−0.1–1.0) | 0.39 |

| NYHA class n (%) | I: 27 (15) | 11(10) | 0.04 |

| II: 84 (45) | 40 (36) | ||

| III: 69 (37) | 59 (53) | ||

| IV: 6 (3) | 1 (1) | ||

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 66 (60–75) | 68 (61–76) | 0.63 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 112 (100–130) | 112 (100–135) | 0.17 |

| Hypertension (%) | 69 | 74 | 0.43 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (%) | 86 | 80 | 0.26 |

| Diabetes (%) | 30 | 32 | 0.61 |

| Smoking (ever; %) | 73 | 70 | 0.69 |

| Family history (%) | 53 | 54 | 0.97 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (1.0–1.4) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.93 |

| Peripheral artery occlusive disease (%) | 12 | 16 | 0.39 |

| Coronary artery disease (1/2/3 vessel disease; %) | 23/30/47 | 23/28/49 | 0.55 |

| Previous bypass operation (%) | 38 | 42 | 0.46 |

| Time from last AMI (months) | 53 (13–122) | 72 (18–156) | 0.15 |

| Atrial fibrillation on admission (%) | 11 | 12 | 1.0 |

| ICD (%) | 24 | 23 | 1.0 |

| CRT (%) | 0.5 | 3.6 | 0.05 |

| CRT-D (%) | 5.4 | 2.7 | 0.28 |

| Mitral regurgitation (grade) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 1.0 (0.5–1.5) | 0.33 |

| Quantitative LVEF (%) | 39 (29–47)a | 36 (28–44)b | 0.09 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 (137–141) | 140 (138–142) | 0.35 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 14 (13–15) | 14 (13–15) | 0.30 |

| White blood count (/nL) | 7 (6–9) | 7 (6–9) | 0.18 |

| Lymphocyte count (%) | 25 (21–27) | 25 (21–27) | 0.14 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.94 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 7 (6–8) | 7 (5–9) | 0.83 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 162 (136–189) | 168 (139–194) | 0.06 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 770 (339–2522)c | 1023 (426–2299)d | 0.39 |

| Antiplatelet therapy (%) | 97 | 97 | 1.00 |

| Oral anticoagulant therapy (%) | 30 | 35 | 0.44 |

| ACEI or ATRB (%) | 95 | 96 | 0.58 |

| Beta-blocker (%) | 95 | 89 | 0.11 |

| Diuretic (%) | 83 | 87 | 0.41 |

| Statin (%) | 91 | 91 | 1.0 |

| Aldosterone blocker (%) | 43 | 48 | 0.47 |

a n = 156.

b n = 93.

c n = 183.

d n = 107.

Table 2.

Cell characteristics

| Single treatment | Repeated treatment |

P value (single vs. first repeated) | P value (first vs. second Tx) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 186) Median (IQR) |

First Tx (n = 111) Median (IQR) |

Second Tx (n = 111) Median (IQR) |

|||

| Cell number (×106 mononuclear cells) | 168 (109–254) | 151 (93–240) | 123 (80–200) | 0.20 | 0.07 |

| SDF-1-induced migration capacity | 90 (59–146) | 97 (61–142) | 104 (65–155) | 0.72 | 0.61 |

| Colony-forming unit capacity | 23 (16–38) | 20 (14–32) | 20 (13–28) | 0.02 | 0.29 |

| CD45+CD34+ cells (%) (assay 1a, n = 181) | 2.1 (1.2–2.9) (n = 114) | 1.8 (0.8–2.5) (n = 44) | 2.0 (0.9–3.1) (n = 23) | 0.34 | 0.92 |

| CD45+CD34+ cells (%) (assay 2a, n = 220) | 1.3 (1.1–1.8) (n = 65) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) (n = 67) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) (n = 88) | 0.99 | 0.90 |

aThe FACS protocol and antibodies were changed during the ongoing registry.

Overall mortality of the study cohort was 7.8% [SE 1.6, 95% confidence interval (CI): 5.3–11.5%] at 1 year, 12.3% (SE 1.9, 95% CI: 9.4–17.1%) at 2 years, and 18.7% (SE 2.3, 95% CI: 14.7%–23.8%) at 3 years. Of the 58 patients who died up to 3-year follow-up, 30 patients died from progressive pump failure, 3 patients from sudden cardiac death, 2 from myocardial re-infarction, and 1 from pulmonary embolism. Ten patients died of non-cardiac death and cause of death could not be determined in 12 patients. One patient underwent heart transplantation and another received a left ventricular assist device. Both these patients were classified as death due to progressive pump failure. Patients who died during follow-up were significantly older, had increased heart rate, creatinine and NT-proBNP serum levels, and higher functional NYHA class, but lower systolic blood pressure and LVEF at inclusion into the registry (see Supplementary material online, Table S2). Moreover, SHFM score was higher in patients who died during the 3-year follow-up time, reflecting more advanced heart failure. This is also evident from more intensive medical therapy and more frequent presence of an ICD. Interestingly, patients who died had undergone repeated cell administration less frequently than survivors (P = 0.048).

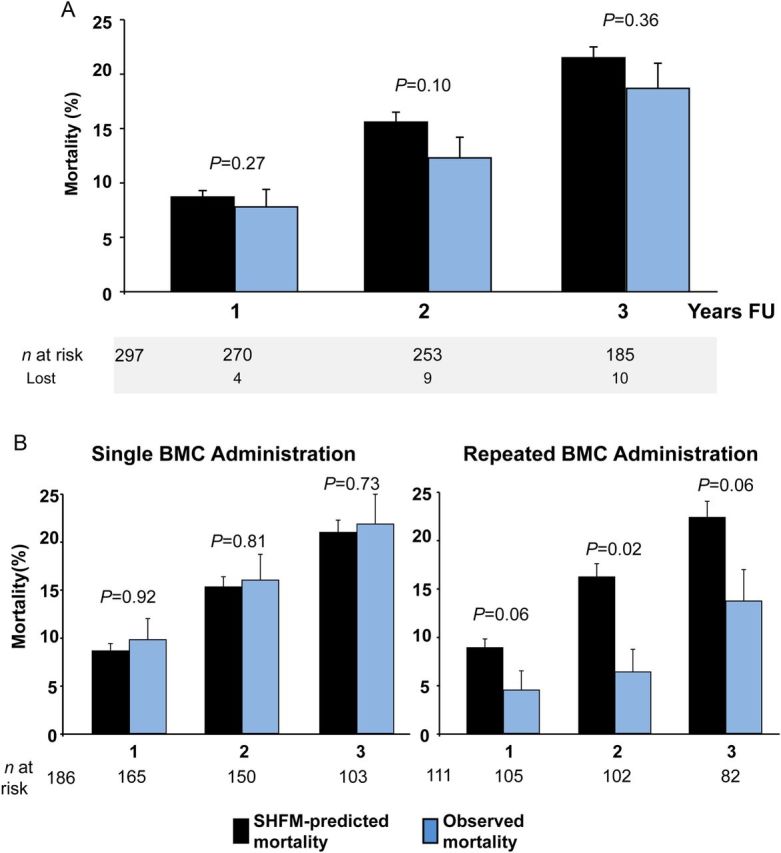

Observed and model-predicted mortality

As illustrated in Figure 1A, observed mortality was consistently lower than model-predicted mortality throughout the 3-year follow-up period. Importantly, the difference between observed and model-predicted mortality was almost entirely driven by a profound mortality risk reduction in patients receiving repeated administrations of BM-MNC, whereas patients receiving a single BM-MNC administration exhibited mortality rates similar to model-predicted mortality (Figure 1B). Most notably, SHFM-predicted mortality did not significantly differ between patients receiving repetitive administration of BM-MNC compared with those receiving only a single treatment. In addition, as summarized in Table 1, patients receiving repeated cell administration did not differ from patients receiving single treatment with respect to any of the baseline characteristics, except that repeatedly treated patients were significantly older, and had trends towards more advanced heart failure symptoms and an even lower LVEF compared with patients receiving single treatment. These data reduce the likelihood that selection bias towards less severe heart failure in patients receiving repeated BM-MNC.

Figure 1.

(A) Seattle Heart Failure Model-predicted mortality (black) and observed mortality (blue) of the total study cohort. (B) Seattle Heart Failure Model-predicted mortality (grey) and observed mortality (black), separated by single and repeated treatment. Standard errors were derived from Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Figure 2A illustrates the Cox regression survival curves adjusted for SHFM score, showing a significantly better outcome for patients receiving repeated BM-MNC treatment compared with the single BM-MNC treatment group (HR 0.53, 95% CI: 0.30–0.94, P = 0.03). In order to account for a survival selection bias for patients undergoing repeated cell administration, the analysis was repeated on a landmark basis. After censoring all patients who were dead (n = 7) or lost to follow-up (n = 1) until 3 months after the first cell administration, multivariable Cox regression analysis still suggests that repeated BM-MNC administration may be a predictor for improved survival (HR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.33–1.06, P = 0.08). Likewise, cox regression analysis for the combined endpoint death and rehospitalization for heart failure showed a significantly better event-free survival in the total cohort analysis (HR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.36–0.95, P = 0.03), and a strong trend towards better outcome for the repeated treatment group in the landmark analysis (HR 0.61, 95% CI: 0.37–1.01, P = 0.06; Figure 2B).

Discussion

The results of the present registry analysis demonstrate that observed mortality rates compare favourably with predicted mortality according to the SHFM score in patients receiving intracoronary administration of BM-MNC for treatment of chronic post-infarction heart failure. However, the reduction of observed compared with predicted mortality appears to be confined to patients receiving repeated cell administration.

The SHFM score, which uses widely available clinical variables to predict mortality in heart failure9 and also incorporates the impact of concurrent medical and device therapy,11,12 has been extensively validated in several patient cohorts including patients with chronic post-infarction heart failure. Given that patients providing informed consent to be included into a study (as also performed in the present registry study) will automatically have a lower risk than an unselected population, it is important to stress that validation of the SHFM has been performed in patients included into randomized trials, the largest of which being the Val-HeFT trial.13 Importantly, 1-year (90.9%), 2-year (83.9%), and 3-year (77.4%) survival rates in Val-HeFT are essentially identical to those predicted for the study cohort of the present work, with 91% at 1 year, 87% at 2 years, and 80% at 3 years, respectively. Thus, the externally derived SHFM clinical risk predictor model appears to be appropriately suited to detect a potential role for intracoronary BM-MNC administration to modify mortality in the patients with chronic heart failure of the present study.

The observation of the present study that risk reduction appears to be confined to patients receiving repeated cell administrations does not come as a surprise. Adverse left ventricular remodelling processes operate for years following an AMI, leading to an enlargement of the left ventricle with extensive fibrosis, which constitutes the pathomorphological substrate of post-infarction heart failure.14 Given the limited plasticity of adult BM-MNC to contribute to contractile recovery of the infarct scar tissue,15 one cannot expect a single BM-MNC administration to have a sustained effect on cardiac functional recovery. It is currently assumed that potential beneficial effects of autologous BM-MNC are mediated by the release of paracrine factors from the retained cells to enhance endogenous repair mechanisms and improve the function of the coronary microcirculation.16,17 The data of the present study suggest that repeated intracoronary cell administrations are required to modify the chronic disease process in patients with chronic post-infarction heart failure with a median time lag of 60 months after the most recent AMI. However, we cannot comment whether intramyocardial injection of cells may also require repetitive treatment. The only other study which investigated repeated cell administration in the setting of chronic heart failure, the DanCell study, recently reported 7-year follow-up clinical data of the 32 patients, who received intracoronary infusion of autologous BM-MNC.18 At 7 years, mortality was 31%, and patients, who received a higher number of CD34+ cells, showed a better survival compared with patients who received low numbers of CD34+ cells, a finding which remained significant in a multivariate analysis. However, the trial comprised only 32 patients compared with our 297 patients, and no comparison was performed to a control group or heart failure score. Of note, in DanCell, although ∼10 times higher cell numbers were intracoronarily injected, there are no cell functional data available, which could also correlate with clinical outcome.19

Limitations

Although the present registry analysis is by far the largest cohort of patients with chronic post-infarction heart failure undergoing intracoronary cell therapy with a total time at risk of 821 patient-years, our study has several important limitations. First and most importantly, patients were not randomized to receive single or repeated BM-MNC administration. Thus, although baseline characteristics and SHFM-predicted mortality did not differ between patients receiving single or repeated BM-MNC administration, and even though we performed a landmark analysis in order to exclude a survival selection bias, we cannot fully exclude a potential selection bias, which might not be reflected in model-estimated risk prediction. Secondly, we limited the duration of follow-up to 3 years which might be an issue. However, recent large trials evaluating a potential benefit of both pharmacological and device therapy on prognosis in patients with chronic heart failure are generally designed to cover a 2–3 years observation period.13,20–22 Thirdly, we did not analyse potential effects of BM-MNC administration on parameters of left ventricular function or quality of life, but rather focused on a single hard endpoint, which was all-cause mortality. Fourthly, the study cohort comprises a consecutive series of all patients treated for post-infarction heart failure by intracoronary BM-MNC administration at a single centre with a highly experienced core lab for cell processing applying rigorous quality standards. Given that the quality of cell processing has a major impact on BM-MNC functionality and efficacy,23 the observations of the present study may not be extrapolated to clinical trials using different cell types or different cell processing techniques. Finally, although survival and the reduction of the combined endpoint of death and rehospitalization for heart failure were significantly different by Cox regression analysis in favour of the repeated treatment group, the effect lost its significance in the landmark analysis. Although the remaining trend still favoured the repeated treatment group with respect to improved outcome, the limited number of hard clinical events like death and rehospitalization for heart failure is, to our opinion, responsible for the loss of significance.

Thus, taken together, the results of the present registry analysis provide the framework and rationale for a prospective randomized multicentre trial, which will clarify whether intracoronary administration of BM-MNC is capable to reduce mortality in patients with chronic post-infarction heart failure (REPEAT trial). The trial essentials of this currently recruiting study (NCT 01693042) can be found in the Supplementary material online, Appendix.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Authors’ contributions

B.A. and E.H.: performed statistical analysis. A.M.Z.: handled funding and supervision. S.D.R., S.A., and H.B.: acquired the data. B.A., A.M.Z., and S.D.: conceived and designed the research. B.A. and A.M.Z.: drafted the manuscript. S.D., A.M.Z., E.H., H.B., and W.C.L.: made critical revision of the manuscript for key intellectual content.

Funding

The REPEAT trial is supported by the LOEWE (Landes-Offensive zur Entwicklung Wissenschaftlich-ökonomischer Exzellenz) Center for Cell and Gene Therapy (State of Hessen).

Conflict of interest: B.A. reports grants from LOEWE Center for Cell and Gene Therapy (State of Hessen) during the conduct of the study. S.D.R., S.A., and H.B. have nothing to disclose. E.H. reports grants from DZHK (Grant from German Federal Ministry of Education and Research) during the conduct of the study. W.C.L. reports being member of Clinical Endpoint Committees (Novartis, St Jude Medical), member of Steering Committees (GE Healthcare), Consultant (Abbott, Biotronik, and HeartWare), and having research grants from NIH, HeartWare, Thoratec, GE Healthcare, in addition to being local PI of clinical trials (Resmed, Novartis, Alnylam, Amgen). S.D. and A.M.Z. report that they are cofounders of t2cure, a for-profit company focused on regenerative therapies for cardiovascular disease. They serve as scientific advisers and are shareholders. In addition, A.M.Z. reports grants from Government during the conduct of the study; and being scientific advisor of Sanofi/Aventis, outside the submitted work.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Willey JZ, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2015;131:e29–e322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shafazand M, Schaufelberger M, Lappas G, Swedberg K, Rosengren A. Survival trends in men and women with heart failure of ischaemic and non-ischaemic origin: data for the period 1987-2003 from the Swedish Hospital Discharge Registry. Eur Heart J 2009;30:671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malliaras K, Marban E. Cardiac cell therapy: where we've been, where we are, and where we should be headed. Br Med Bull 2011;98:161–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forbes SJ, Rosenthal N. Preparing the ground for tissue regeneration: from mechanism to therapy. Nat Med 2014;20:857–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jeevanantham V, Butler M, Saad A, Abdel-Latif A, Zuba-Surma EK, Dawn B. Adult bone marrow cell therapy improves survival and induces long-term improvement in cardiac parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2012;126:551–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clifford DM, Fisher SA, Brunskill SJ, Doree C, Mathur A, Clarke MJ, Watt SM, Martin-Rendon E. Long-term effects of autologous bone marrow stem cell treatment in acute myocardial infarction: factors that may influence outcomes. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e37373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Assmus B, Honold J, Schachinger V, Britten MB, Fischer-Rasokat U, Lehmann R, Teupe C, Pistorius K, Martin H, Abolmaali ND, Tonn T, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Transcoronary transplantation of progenitor cells after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1222–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diederichsen AC, Moller JE, Thayssen P, Junker AB, Videbaek L, Saekmose SG, Barington T, Kristiansen M, Kassem M. Effect of repeated intracoronary injection of bone marrow cells in patients with ischaemic heart failure the Danish stem cell study--congestive heart failure trial (DanCell-CHF). Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10:661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, Anand I, Maggioni A, Burton P, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Mann DL, Packer M. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation 2006;113:1424–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Assmus B, Schachinger V, Teupe C, Britten M, Lehmann R, Dobert N, Grunwald F, Aicher A, Urbich C, Martin H, Hoelzer D, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Transplantation of Progenitor Cells and Regeneration Enhancement in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TOPCARE-AMI). Circulation 2002;106:3009–3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mozaffarian D, Anker SD, Anand I, Linker DT, Sullivan MD, Cleland JG, Carson PE, Maggioni AP, Mann DL, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Levy WC. Prediction of mode of death in heart failure: the Seattle Heart Failure Model. Circulation 2007;116:392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levy WC, Lee KL, Hellkamp AS, Poole JE, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Maggioni AP, Anand I, Poole-Wilson PA, Fishbein DP, Johnson G, Anderson J, Mark DB, Bardy GH. Maximizing survival benefit with primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in a heart failure population. Circulation 2009;120:835–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cohn JN, Tognoni G. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1667–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sutton MG, Sharpe N. Left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: pathophysiology and therapy. Circulation 2000;101:2981–2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM, Schneider MD. Unchain my heart: the scientific foundations of cardiac repair. J Clin Invest 2005;115:572–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Erbs S, Linke A, Schachinger V, Assmus B, Thiele H, Diederich KW, Hoffmann C, Dimmeler S, Tonn T, Hambrecht R, Zeiher AM, Schuler G. Restoration of microvascular function in the infarct-related artery by intracoronary transplantation of bone marrow progenitor cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Doppler Substudy of the Reinfusion of Enriched Progenitor Cells and Infarct Remodeling in Acute Myocardial Infarction (REPAIR-AMI) trial. Circulation 2007;116:366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chavakis E, Koyanagi M, Dimmeler S. Enhancing the outcome of cell therapy for cardiac repair: progress from bench to bedside and back. Circulation 2010;121:325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hansen M, Nyby S, Eifer Moller J, Videbaek L, Kassem M, Barington T, Thayssen P, Diederichsen AC. Intracoronary injection of CD34-cells in chronic ischemic heart failure: 7 years follow-up of the DanCell study. Cardiology 2014;129:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Assmus B, Fischer-Rasokat U, Honold J, Seeger FH, Fichtlscherer S, Tonn T, Seifried E, Schächinger V, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Transcoronary transplantation of functionally competent BMCs is associated with a decrease in natriuretic peptide serum levels and improved survival of patients with chronic postinfarction heart failure: results of the TOPCARE-CHD Registry. Circ Res 2007;100:1234–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005;352:225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Yusuf S, Pocock S. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet 2003;362:759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999;341:709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seeger FH, Tonn T, Krzossok N, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Cell isolation procedures matter: a comparison of different isolation protocols of bone marrow mononuclear cells used for cell therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2007;28:766–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.