Abstract

Purpose

Despite the existence of minimum age laws for juvenile justice jurisdiction in 18 US states, California has no explicit law that protects children (i.e. youth less than 12 years old) from being processed in the juvenile justice system. In the absence of a minimum age law, California lags behind other states and international practice and standards. The paper aims to discuss these issues.

Design/methodology/approach

In this policy brief, academics across the University of California campuses examine current evidence, theory, and policy related to the minimum age of juvenile justice jurisdiction.

Findings

Existing evidence suggests that children lack the cognitive maturity to comprehend or benefit from formal juvenile justice processing, and diverting children from the system altogether is likely to be more beneficial for the child and for public safety.

Research limitations/implications

Based on current evidence and theory, the authors argue that minimum age legislation that protects children from contact with the juvenile justice system and treats them as children in need of services and support, rather than as delinquents or criminals, is an important policy goal for California and for other national and international jurisdictions lacking a minimum age law.

Originality/value

California has no law specifying a minimum age for juvenile justice jurisdiction, meaning that young children of any age can be processed in the juvenile justice system. This policy brief provides a rationale for a minimum age law in California and other states and jurisdictions without one.

Paper type

Conceptual paper

Keywords: Criminal justice system, Public health, Health policy, Human rights, Young offenders, Juvenile offenders

Overview

This policy brief examines evidence, theory, and policy related to setting a minimum age for juvenile delinquency jurisdiction (i.e. minimum age law) in the state of California. The paper provides background on the juvenile justice system in California and minimum age laws; summarizes research evidence relevant to children who come into conflict with the law; provides professional association recommendations; and based on the aforementioned topics, asserts our policy recommendations for California, recommendations that are relevant for other US states and countries lacking a minimum age statute. For this policy brief, the term “children” refers to youth less than 12 years old.

Background

Youth arrest and incarceration rates in the USA far exceed those of any other developed country (Hazel, 2008). US law enforcement officials make over 1.3 million arrests of juveniles or minors (i.e. children and adolescents under 18 years old) each year (Puzzanchera, 2014). Moreover, following the prison boom of the 1980s and 1990s, by the year 2000, the youth incarceration rate in the USA was roughly seven times higher than in England and 3,000 times higher than in Japan (Hazel, 2008). Differing from the conventions of most other nations, US state laws, rather than federal ones, specify the parameters for prosecuting and sentencing minors in juvenile court, resulting in state by state policy variations. One such variation is the minimum age at which a child can be prosecuted in juvenile court under state law, referred to as the minimum age of juvenile justice jurisdiction.

The state of California is home to over 39 million people, making it the most populous state in the USA (United States Census Bureau, 2016). In 2014, California arrested 86,823 youth; the most of any other US state. Of these, over 81 percent of California's arrested youth were charged, turned over to probation, or transferred to adult court (California Department of Justice, 2014). California's rate of correctional placement is 197 per 100,000 juveniles, compared to an average of 176 per 100,000 across the USA (Sickmund et al., 2015). The California juvenile justice system is largely county run, and its vast majority of juvenile corrections facilities are administered by the 58 separate county probation service offices.

All US states have laws that protect children and adolescents from being tried in adult criminal courts and that limit the use of harsh sentences for crimes committed as juveniles. California state law stipulates that a young person must be at least 14 years of age in order to be charged as an adult in criminal court (California State Legislature, 2000). However, despite the recent upsurge of reform efforts focused on protecting minors from adult criminal proceedings, relatively little attention has been paid to children in the juvenile justice system. At present in California, there is no law that protects children from being charged and processed in the juvenile justice system. Indeed, children can be subject to formal processing in juvenile court, including detention and confinement, a process that research and best practices would suggest is counter to the standard of the “best interests of the child.” The “best interests of the child” is one of the founding principles of the US juvenile justice system and is the operating standard in child welfare law and in the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (United States Children's Bureau, 2012; United Nations General Assembly, 1989).

Establishing a minimum age of juvenile justice jurisdiction aligns with international human rights standards. Article 40 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) declared that all nations set a minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) below which no child would be subject to formal prosecution. Subsequently, Article 4 of the Beijing Rules specified that this MACR be no younger than 12, and encouraged states not to lower their MACR to 12 if they were set higher (United Nations, 2007).

Following this doctrine, the majority of Western European countries have set the minimum age of juvenile justice jurisdiction at age 12 or even higher (Hazel, 2008). In Finland, no child under age 15 can be subject to any type of criminal prosecution, and children under 18 are incarcerated only in rare circumstances. Other European countries, such as Germany and Austria, have specified the age of “criminal responsibility” (a term often used in an international context to refer to the minimum age of juvenile justice jurisdiction) at 14 (Hazel, 2008).

Leading the way on policies underscored by an understanding of the process of child and adolescent maturation, many countries have set gradated penalties based on various age categories, as determined by national law, as a way to protect children from contact with the justice system (Child Rights International Network, 2016). For example, the Finnish Criminal Code mandates that sentences for criminal offenses be doled out at one-third of an adult sentence for youth aged 15-17, and two-thirds of an adult sentence for those aged 18-20 (Pitts and Kuula, 2005). Moreover, Germany's law provides the option of trying young adults up to age 21 in juvenile court rather than in adult court (Hazel, 2008). Hence, rather than supervising, prosecuting, or detaining young people under a given age threshold (often age 12 or higher), these countries have implemented procedures for educational, child protection, social services, or family support interventions for children who have committed an act that would be deemed illegal if the child were older. Despite wide variation in how alternatives to formal court processing or sanctions are implemented, monitored, and applied, these countries share an important commonality – their laws protect children from contact with the justice system altogether.

The USA remains the only member of the United Nations that has not endorsed the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, a decision that has drawn sharp criticism from international allies (Hazel, 2008). There is no federal statute regarding the minimum age of juvenile justice jurisdiction. In the majority of states, statutes, common law, court rules, or precedents determine the minimum age at which a child can be processed in the juvenile justice system. As of 2014, 18 states had established a minimum age threshold for juvenile delinquency jurisdiction: one state has set a minimum age of six years old, four states have set an age of seven, one state has set an age of eight, and 12 states have set an age of ten (National Center for Juvenile Justice, 2016). California has an opportunity to be a leader in advancing a minimum age that aligns more closely with international human rights standards.

In considering a potential policy change, it is important to examine current data on children under 12 who are formally processed in the juvenile justice system across the state. According to the State of California's Department of Justice (2016):

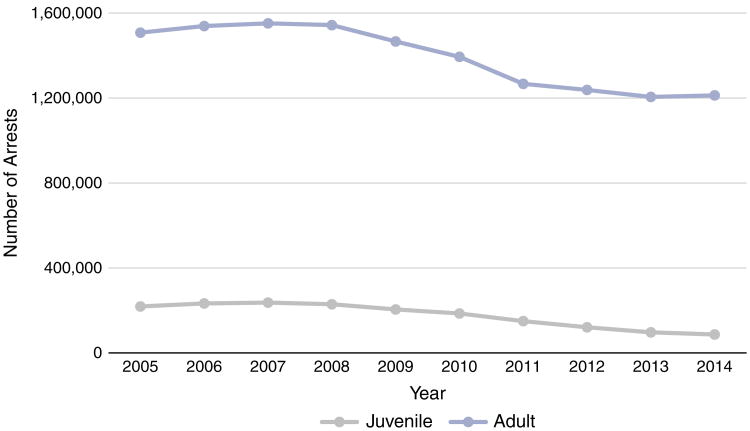

In California, trends in both adult and juvenile arrests have decreased over the last ten years. Juvenile arrests have decreased from over 218,000 in 2005 to just over 86,000 in 2014 (Figure 1).

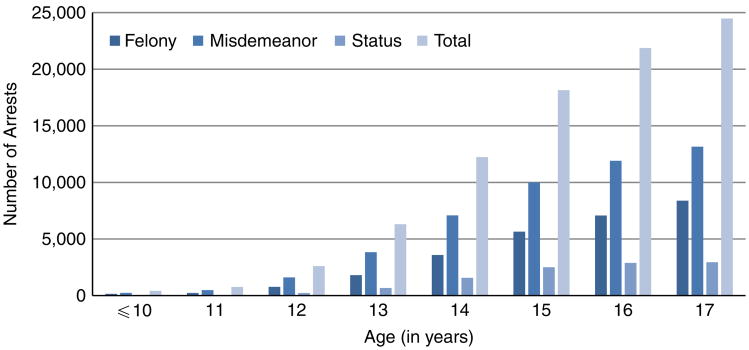

In 2014, of the 86,823 juveniles arrested in California, 1,181 were under age 12. Of these, 420 were ten years old or younger (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Juvenile and adult arrests in California (2005-2014).

Note: “Juvenile” refers to minors less than 18 years old

Source: State of California, Department of Justice, Crime Statistics; https://oag.ca.gov/crime

Figure 2. Juvenile arrests in California by age and reported offense (2014).

Notes: “Juvenile” refers to minors less than 18 years old. Reported offense categories include felony, misdemeanor, and status offense. A “status offense” is an act that is only deemed illegal because of the young age of the offender. Status offenses include truancy and running away

Source: State of California, Department of Justice, Crime Statistics; https://oag.ca.gov/crime

Although these data indicate that overall arrest rates are declining and that children represent a small proportion of juvenile arrests in the state, it is nevertheless important to address the needs of this extremely vulnerable group and avoid any reversal in downward trends.

Evidence: formal juvenile justice system involvement harms children

Research has found that children in the juvenile justice system are already a very vulnerable group. Compared to their non-justice-involved peers, children who are arrested or charged with a crime are significantly more likely to have histories of child maltreatment, learning problems, or underlying, unaddressed behavioral health conditions (Loeber et al., 2003). Up to 90 percent of court-involved youth report exposure to some type of traumatic event, often first occurring within the first five years of life. Subjecting victimized children to court proceedings and/or confinement may indeed further perpetuate cycles of victimization and maladaptive responses (Dierkhising et al., 2013).

Decades of research, including rigorous systematic reviews, have shown that formally processing youth in the juvenile justice system does not result in preventing future crime, but instead increases the likelihood of future criminal behavior (Petrosino et al., 2010). Early contact with the juvenile justice system has a negative prognosis on future behaviors that increases inversely with age of first contact. Without receipt of appropriate treatment, individuals who first become involved in the justice system as children are more likely to become chronic offenders – a pattern that can continue into adulthood (Loeber et al., 2003). Additionally, incarceration itself likely hinders youths' healthy development as secure confinement has been shown to have a detrimental effect on youths' development of psychosocial maturity (Dmitrieva et al., 2012). Alternatives to formally processing children in the juvenile justice system – such as by increasing the use of community-based treatment programs – can be more effective in promoting positive pathways to healthy lifestyles and rehabilitation (Loeber et al., 2003).

Science and law: the young brain and criminal capacity, competency, and responsibility

Both science and the law have long recognized the vulnerabilities of youth; this was the original premise of creating a separate juvenile system oriented toward treatment and rehabilitation (Greenwood and Turner, 2011). Cognitive and psychosocial development exists along a continuum and accordingly, children's developmentally appropriate psychosocial immaturity can play a direct role in offending. Because qualities such as impulse control and future orientation do not become fully developed in the brain until adulthood, many researchers contend that children are morally less responsible and therefore less legally culpable for criminal behavior compared to adults (Cauffman and Steinberg, 2000; Steinberg et al., 2009). Indeed, advances in science have confirmed that young people do not reach neurocognitive maturity until at least their mid-20s (Giedd, 2004).

Findings from developmental and neuroscience research have informed four recent US Supreme Court decisions, reflecting an evolving understanding of the interplay among criminal culpability, neurocognitive development, and adolescent behavior (Bath et al., 2013). These trends in jurisprudence have resulted in enhanced due-process protections for children and have pushed the justice system toward a developmental approach in considering culpability. Specifically, Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005), abolished the juvenile death penalty. Subsequently, Graham v. Florida, 130 S. Ct. 2011 (2010), found that sentencing adolescents to life without parole for a crime other than homicide violates the 8th Amendment; Miller v. Alabama, 132 S. Ct. 2455 (2012) extended the Graham decision to abolish mandatory life without parole for all youth and require judicial consideration of all mitigation, including age and psychosocial factors, before life without parole can be imposed; and the recent Montgomery v. Louisiana case (2016) applied Miller retroactively (Bath et al., 2013).

In all of these cases, the majority arguments noted that a young person's inherent developmental immaturity and malleability renders them less blameworthy for their crimes relative to adults, and because of this malleability, their capacity for change over time and amenability to rehabilitative efforts is greater as compared to adults.

The recurring conclusion that age matters has been expressed in myriad areas of law – including in assessing a youth's very ability to understand and engage in legal proceedings. Juvenile competency to stand trial, also referred to as adjudicative competence, is perhaps one of the most basic and bedrock components of due-process safeguards in the justice system; the concept requires a youth to have a rational and factual understanding of the proceedings against him or her and be able to consult with his or her lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding. Many youth, particularly children under 12, lack adjudicative competency to understand legal proceedings in the juvenile justice system (Bath and Gerring, 2014). Numerous studies have documented that youth under age 15 struggle with adjudicative competence and are at risk for being found incompetent to stand trial during court proceedings (Grisso, 2005). As the appreciation of developmental differences between youth and adults grows, the understanding of adjudicative competency also has evolved to consider development as part of the equation and has resulted in important legislative changes.

The California case of Timothy J (2007) 150 Cal. App. 4th 847, further underscores the importance of considering age-related developmental immaturity as a potential predicate for being found incompetent to stand trial. In that case, the court-appointed psychologist concluded that the 11-year-old defendant “had little or no concept of the future, so the idea of prolonged punishment or supervision had no meaning to him and because he had not yet developed a desire to be independent of his parents, the impositions of physical restrictions would not have the same meaning and effect on him as it would have on an adult.” The psychologist further concluded that the child “would defer to his parents or his attorney to make decisions regarding his case, that if he disagreed with them, he would not be able to stand up for himself, and that he is not able to appreciate the long-term effects of his decisions.”

Prior to Timothy J, only mental illness or developmental disorders could be used as reasons for a finding of incompetency in youth. The court's decision in the Timothy J case marked a definitive recognition that age alone can be a key basis for such a finding. As of 2014, California became one of 21 states with a specific juvenile competency statute (AB 2212) and one of 14 to recognize developmental immaturity as a potential predicate for a finding of incompetency (Bath and Gerring, 2014).

Other areas of research into the criminal justice process have echoed an appreciation of children's developmental differences and their limited capacities for comprehension of their rights and of the justice system process. These include youth's difficulty in comprehending their Miranda rights during arrest (Grisso et al., 2003), as well as during interrogation, when youth, especially children, are more highly prone to falsely confess (Malloy et al., 2014). Indeed, there has also been long-standing recognition that whole categories of youth may not even be able to form criminal intent. Common law doctrine rooted in custom and court decisions has typically found that children under seven completely lack criminal capacity, while children between 7 and 14 are presumed to also lack criminal capacity. In California, the Supreme Court recognized this presumption in a 1970 case, In re Gladys R, 1 C3d 855, which requires “clear proof” that “a child under the age of 14 years at the time of committing the act appreciated its wrongfulness.”

The extent to which the existing protections for children are applied and adhered to in practice – both in terms of competency (as established after the Timothy J case) and capacity (per In re Gladys R) – is unclear.

Professional association recommendations

A growing body of research demonstrates the vulnerabilities of children. In response to this, professional associations from several fields have adopted standards regarding juvenile justice jurisdiction and law. Key examples are as follows:

The National Academy of Sciences recommends using developmental research to guide juvenile justice decision making (National Research Council, 2013).

The American Academy of Pediatrics officially recognizes incarcerated youth as a high-risk group of children and adolescents who have high rates of unmet medical, developmental, and mental health needs. The Academy called to reduce the number of youth confined in the USA and for all confinement to be developmentally appropriate (American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence, 2011).

The American Bar Association (1977) asserted that children under the age often (at the time of the offense) should not be prosecuted in even a juvenile court.

Recommendations

In alignment with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, we suggest that children younger than at least 12 years of age should be protected from juvenile court proceedings. This applies to all jurisdictions currently without a minimum age policy, and particularly for jurisdictions like the state of California whose juvenile justice system effects the lives of thousands of children and their families each year. Additionally, policies and further research are needed to ensure the most appropriate treatment for children who exhibit early anti-social behavior, including “delinquent” acts. Policies that re-direct children to effective alternatives to incarceration are an important first step. Additional studies are needed to further characterize the scope of this issue and identify appropriate reforms, including efforts to: identify the impact of formal justice system contact on the short and long-term physical and mental health outcomes of youth; identify evidence-based ways to address the unmet mental health, physical health, and social needs of children who exhibit delinquent behaviors; and develop a deeper understanding of diversion programs and other alternatives to incarceration for children. Together, this type of work can move criminal justice jurisdictions, including California, toward developing and implementing evidence-based policies that re-direct children in contact with the justice system to effective, alternative pathways that optimize their health and enhance public safety. A critical step in this process is developing a minimum age law (of 12 or higher) for juvenile justice jurisdiction in all US states and nations currently lacking such a law, including the state of California.

Conclusion

The best ways to address the needs of children who exhibit delinquent behaviors must be carefully evaluated and reframed within a neurodevelopmental framework. Minimum age legislation that excludes children younger than 12 years of age (or higher) from contact with the juvenile justice system is an important policy goal for the state of California and other states and jurisdictions lacking a minimum age statute.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a seed grant from the UC Criminal Justice & Health Consortium and by a UCLA Transdisciplinary Seed Grant to the first and second author. Dr Barnert was supported by a grant from the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000124) and the UCLA Children's Discovery and Innovation Institute. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or the official position of the affiliated institutions.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth S. Barnert, Juvenile Justice Working Group, University of California Criminal Justice and Health Consortium, California, USA and the Department of Pediatrics, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA

Laura S. Abrams, Juvenile Justice Working Group, University of California Criminal Justice and Health Consortium, California, USA and the Department of Social Welfare, Luskin School of Public Affairs, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA

Cheryl Maxson, Juvenile Justice Working Group, University of California Criminal Justice and Health Consortium, California, USA and the Department of Criminology, Law and Society, Irvine School of Social Ecology, University of California, Irvine, California, USA.

Lauren Gase, Juvenile Justice Working Group, University of California Criminal Justice and Health Consortium, California, USA and the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Patricia Soung, Children's Defense Fund-California, California, USA.

Paul Carroll, Juvenile Justice Working Group, University of California Criminal Justice and Health Consortium, California, USA and the Department of Psychology, University of California, Merced, California, USA.

Eraka Bath, Juvenile Justice Working Group, University of California Criminal Justice and Health Consortium, California, USA and the Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence. Health care for youth in the juvenile justice system. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1219–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Bar Association. Standards Related to Juvenile Delinquency and Sanctions. American Bar Association; Washington, DC: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bath E, Gerring J. National trends in juvenile competency to stand trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):265–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath E, Sidhu S, Stepanyan ST. Landmark legislative trends in juvenile justice: an update and primer for child and adolescent psychiatrists. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(7):671–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Justice. Juvenile Justice in California. California Department of Justice; Sacramento, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- California State Legislature. California Welfare and Institutions Code 602b 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Steinberg L. (Im)maturity of judgment in adolescence: why adolescents may be less culpable than adults. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2000;18(6):741–60. doi: 10.1002/bsl.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Rights International Network. Child Rights International Network; 2016. [accessed June 22 2016]. Minimum ages of criminal responsibility in Europe. available at: www.crin.org/en/home/ages/europe. [Google Scholar]

- Dierkhising CB, Ko SJ, Woods-Jaeger B, Briggs EC, Lee R, Pynoos RS. Trauma histories among justice-involved youth: findings from the national child traumatic stress network. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2013 Jul;4:1–12. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva J, Monahan KC, Cauffman E, Steinberg L. Arrested development: the effects of incarceration on the development of psychosocial maturity. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(3):1073–90. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN. Structural magnetic resonance imaging of the adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004 Jun;1021:77–85. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood P, Turner S. Juvenile crime and juvenile justice. In: Wilson J, Petersilia J, editors. Crime and Public Policy. Oxford University Press; Oxford; 2011. pp. 88–129. [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T. Evaluating Juveniles' Adjudicative Competence: A Guide for Clinical Practice. Professional Resource Press; Sarasota, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T, Steinberg L, Woolard J, Cauffman E, Scott E, Graham S, Lexcen F, Reppucci ND, Schwartz R. Juveniles' competence to stand trial: a comparison of adolescents' and adults' capacities as trial defendants. Law and Human Behavior. 2003;27(4):333–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1024065015717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazel N. Cross-National Comparison of Youth Justice. University of Salford; Salford: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington D, Petechuk D. Child Delinquency: Early Intervention and Prevention. US Department of Justice - Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Programs; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Malloy LC, Shulman EP, Cauffman E. Interrogations, confessions, and guilty pleas among serious adolescent offenders. Law and Human Behavior. 2014 Apr;38:181–93. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Juvenile Justice. National Center for Juvenile Justice; 2016. [accessed June 22 2016]. Jurisdictional boundaries. available at: www.jjgps.org/jurisdictional-boundaries. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Reforming Juvenile Justice: A Developmental Approach. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Petrosino A, Turpin-Petrosino C, Guckenburg S. Formal System Processing of Juveniles: Effects on Delinquency. Campbell Systematic Reviews, The Campbell Corporation; Woburn, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts J, Kuula T. Incarcerating young people: an Anglo-Finnish comparison. Youth Justice. 2005;5(3):147–64. [Google Scholar]

- Puzzanchera C. Juvenile arrests 2012 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Sickmund M, Sladky T, Kang W, Puzzanchera C. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2015. [accessed July 8, 2016]. Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement. available at: www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/ [Google Scholar]

- State of California Department of Justice. State of California Department of Justice – Office of the Attorney General; 2016. [accessed June 22, 2016]. Crime data. available at: https://oag.ca.gov/crime. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Graham S, O'brien L, Woolard J, Cauffman E, Banich M. Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development. 2009;81(1):28–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child – General Comment No 10– Children's Rights in Juvenile Justice. United Nations; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations; Geneva: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. accessed July 8, 2016. United States Census Bureau; 2016. Quick facts: California. available at: www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/06,2412150,00. [Google Scholar]

- United States Children's Bureau. Child Welfare Information Gateway, US Children's Bureau; 2012. [accessed June 15, 2016]. Determining the best interests of the child. available at: www.childwelfare.gov/ [Google Scholar]