Objective

The Medicaid Title XIX sterilization forms were mandated in 1976 in order to protect vulnerable women from coercive sterilization.1–3 The forms require a 30-day waiting period between when the form is signed and when sterilization can occur, but does allow for a shorter 72-hour interval prior to postpartum sterilization following premature delivery.1–2 Given the infrastructure of Medicaid, variation could potentially exist in defining the term, “premature delivery,” in a federally mandated but state-based form. Therefore, we sought to survey the practices of obstetricians-gynecologists surrounding the waiting period for postpartum sterilization in the Medicaid population. We hypothesized that there would not be variation in the definition of “premature delivery” given the federal nature of the consent form.

Study Design

This is a prospective, electronic survey-based study of 1000 obstetrician-gynecologist members of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), half of whom are members of the Collaborative Ambulatory Research Network (CARN). CARN members are a demographically-representative group of practicing ACOG members and were randomly selected. Non-CARN members were selected by utilizing proportionate random sampling by ACOG district. The survey instrument was developed in an iterative fashion and pilot-tested. A unique survey link was sent electronically to all participants along with an introductory email message. Five reminder emails and links were sent on a weekly basis if a participant did not complete the survey previously. Responses were anonymous and excluded if incomplete. All analyses were performed using R Version 3.3.0.4 This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of MetroHealth Medical Center.

Results

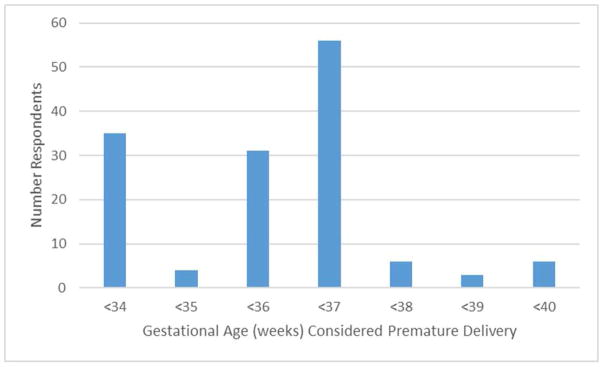

218 of 957 (22.8%) of surveyed physicians responded to the survey, after accounting for exclusions. Of these, 165 (75.7%) were CARN members. 5.9% of respondents were in solo practice, 34.6% in group practice, 18.6% in multispecialty group practice, 13.3% in hospital-based practice, and 18.1% in university-affiliated practice. 89.4% of respondents perform sterilization in their practice. Of those who perform sterilization, 18.6% of respondents utilized delivery prior to 34 weeks, 2.1% utilized 35 weeks, 16.4% utilized 36 weeks, 29.8% utilized 37 weeks, 3.2% utilized 38 weeks, 1.6% utilized 39 weeks, and 3.2% utilized 40 weeks as the definition of premature delivery, thus permitting a 72-hour rather than 30-day waiting period (Figure 1). The remaining 25% of respondents answered “Not Applicable” to this question. There was variation among respondents from within the same state regarding the gestational age they utilized to define premature delivery. Overall, there were no consistent patterns for the variation within or between states by physician or practice demographic characteristics. There were also no significant associations between region of the country for either training or current practice and waiting period utilized. 43% of respondents answered that their hospital had a policy regarding postpartum sterilization. Presence of a hospital policy was associated with use of delivery prior to 37 weeks gestation as the definition of premature delivery (p=0.014).

Figure 1.

Frequency of responses for gestational age used to define “premature labor” and allow for a 72-hour rather than 30-day waiting period for postpartum sterilization.

Conclusion

While caution should be utilized in interpreting statistical relationships as the response rate to our survey is low, it is surprising that there was variation both within and between states regarding the gestational age utilized to define premature delivery. Rationale for this variation was unable to be obtained by the empirical survey methodology. Use of an earlier gestational age leads to a more restrictive sterilization policy and may serve as a barrier to sterilization fulfillment. Additionally, intra-state variation suggests a lack of uniform application of state policy, which is ethically problematic in terms of justice or fairness concerns. We recommend individual obstetrician-gynecologists consistently utilize the waiting period required by their state as well as consider implementing hospital policies to standardize the approach.

Acknowledgments

Funding - Dr. Arora is funded by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, KL2TR000440 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Financial support for this study was provided in part by Grant UA6MC19010 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act, Health Resources and Services Administration, and Department of Health and Human Services). This manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or HRSA.

Laura Morello, MA, LSW and Roselle Ponsaran, MA for their assistance in survey development.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest –The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Block-Abraham D, Arora KS, Tate D, Gee RE. Medicaid consent to sterilization forms: Historical, practical, ethical, and advocacy considerations. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;58(2):409–17. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 530: Access to postpartum sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(1):212–215. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318262e354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrero S, Zite N, Potter JE, et al. Medicaid policy on sterilization—anachronistic or still relevant? N Engl J Med. 2014;370:102–104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1313325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2017. https://R-project.org. [Google Scholar]