Abstract

The frontal lobes are important for cognitive control, yet their functional organization remains controversial. An influential class of theory proposes that the frontal lobes are organized along their rostro-caudal axis to support hierarchical cognitive control. Here, we take an updated look at the literature on hierarchical control, with particular focus on the functional organization of lateral frontal cortex. Our review of the evidence supports neither a unitary model of lateral frontal function nor a unidimensional abstraction gradient. Rather, separate frontal networks interact via local and global hierarchical structure to support diverse task demands.

Keywords: Cognitive control, executive function, frontal lobes

Cognitive control and the functional organization of the frontal lobes

Humans have an unrivaled ability to envision a desired state of affairs and then carry out the actions to achieve it. This capacity to manage goal-directed behaviors in novel situations, counter to habit, or amidst competing action-choices is termed cognitive control [1–3]. In the brain, cognitive control (see Glossary) has a close dependency on the frontal lobes and their associated systems [4]. However, there has been persistent controversy regarding the functional organization of the frontal lobes, whether there exist one or more functionally distinct areas or networks, and how these components interact to support controlled behavior.

Here, we take an updated look at an influential class of hypotheses surrounding the rostro-caudal organization of function in the frontal lobes. Though several variants of this organizing principle have been proposed (reviewed in [5]), the common element has been that rostral frontal areas are involved in more abstract forms of control than more caudal areas. This putative rostro-caudal abstraction gradient has been theorized to support a hierarchical processing architecture of the frontal lobes, wherein abstract goals are actively translated into movements via a rostral-to-caudal flow of processing, and rostral areas of frontal cortex influence and organize processing in posterior areas [6–8]. The last decade has witnessed numerous tests of these basic hypotheses. Here, we revisit the evidence for a hierarchical organization of the frontal lobe and offer a revised framework. Though the evidence supports the hypothesis that the frontal lobes are organized hierarchically, there is likely not a unidimensional gradient of abstraction. Rather, the apex of the hierarchy may be more caudal than previously thought, with rostrolateral prefrontal cortex (RLPFC) supporting a distinct functional role.

What is hierarchical control?

Much of the evidence informing the rostro-caudal organization of frontal cortex has come from studies examining hierarchical cognitive control. In some sense, all cognitive control is hierarchical in that it concerns how top-down contextual signals modulate pathways from stimulus to response. However, hierarchical cognitive control distinguishes those cases wherein actions must be controlled based on immediate contextual signals that are themselves also influenced by one or more superordinate contexts. Managing these multiple levels of contextual contingency at once introduces special problems for the control system (see Box 1).

Box 1. Architectures for Hierarchical Control.

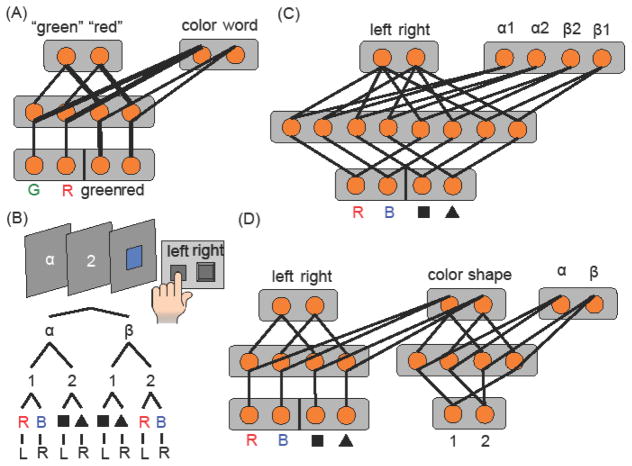

What special problems do hierarchical control tasks pose? To answer this, it is helpful to first consider a simple model of cognitive control. Fig. IA depicts the familiar guided activation model of cognitive control during a Stroop task [91]. Here, control is enacted through a top-down influence from “PFC” units that maintain the task (i.e., “color-naming”) in a context layer. This top-down signal biases the color-naming pathway to win its competition for responding over habitual word-reading.

Fig. IB depicts a hierarchical control problem. In this hypothetical task, the participant must respond to either the color or the shape of a final stimulus with their left or right hand. The shape or color task is cued by a preceding number context. However, the interpretation of this number context is itself contextualized by a Greek letter. This “third order” rule structure can be expressed as a three level hierarchical tree.

This simple increment in rule complexity makes the control problem much harder. To illustrate, consider how one might modify the model in Fig. IA to follow this more complex rule. Even from basic principles of guided activation, there are several qualitatively different ways to solve this problem. The models depicted in Fig. IC–D are representative of two such classes of hypothetical solutions.

The network in Fig. IC is a unitary hub controller architecture. It does not add any new contextual layers to the architecture in Fig IA. Rather, it follows the rule by increasing dimensionality (i.e., a larger number of units) in the associative and context layers to accommodate the separate pathways without overlap. Of course, this model has limitations. For example, as connected, this model loses the hierarchical structure of the rule by effectively flattening the higher contextual layers. This loss of hierarchical structure can make certain types of generalization and transfer difficult.

Fig. ID depicts a hierarchical control architecture. Here, the contextual layer that influences the pathway from low level shape and color inputs to responses is itself controlled by a second network that has access to its own inputs and is influenced by a third contextual layer. Due to their separation, the contextual decisions do not interfere with each other, allowing them to progress in parallel, matching the mostly parallel decision-making dynamics that people exhibit in these higher order rule tasks [92]. Likewise, the network can separately learn when to engage each level of control [93, 94]. And, by preserving hierarchical structure, these architectures can rapidly transfer and generalize [11, 93–95].

Computational models of hierarchical control have largely used hierarchical architectures with separate, interacting context layers [11, 94, 96, 97]. Evidence of rostro-caudal differences in PFC may be in line with the spatially separate controllers required by these architectures. However, others propose that the high dimensional capacity of PFC neural populations [98] can support massive flexibility within a single contextual layer [99]. As noted above, many solutions surely exist to hierarchical control problems, including those not discussed here, such as recurrent networks [100]. However, no model using a non-hierarchical architecture has accounted for the range of effects that hierarchical architectures have captured to date. Nevertheless, as a constraint on theory, it is essential to directly investigate how the brain responds to well-defined hierarchical control problems.

Figure I.

Architectures for hierarchical control. (A) Schematic of the simple model of the Stroop task from [91]. Thick lines depict stronger connection strength. (B) Task schematic and rule structure for a hierarchical control task. A unitary context “hub” (C) and a hierarchical control architecture (D) could both solve this problem, though with different strengths and weaknesses.

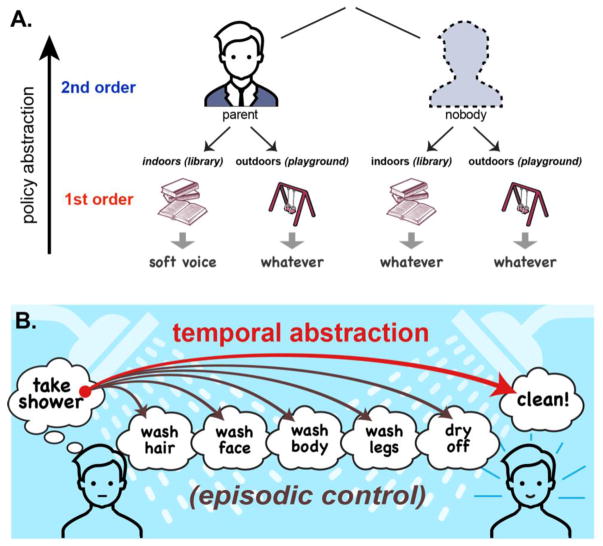

Hierarchical control applies to multi-level rules we follow in everyday life. To illustrate, consider the following example (from [9]) (Fig 1A). Children are often taught, “When inside speak in a soft ‘indoor voice’.” Here, being indoors contextualizes how to speak. However, a savvy child quickly learns that the “indoor voice rule” only applies when a parent is nearby. In this case, the parent provides a superordinate context that determines how other contextual features, like being indoors, should influence behavior. Failing to manage the relationship among these contextual elements properly likely results in a scolding (or wasted effort).

Figure 1.

Hierarchical control demands affecting rostro-caudal activation. (A) Policy abstraction can be operationalized in terms of the depth of decision tree relating contexts to actions. Here, the presence of a parent contextualizes the relation between the environment and speech volume. (B) Temporal abstraction (red curved arrow) refers to contextual representations that are sustained over time and/or abstract over intervening episodes or subtasks. Here, the goal of “take shower” abstracts over several subtasks en route to the goal of being clean. When a temporally abstract context is used to guide control of lower order tasks, rather than information available in the stimulus, this is referred to as episodic control (brown curved arrows). Thus, if prior steps or the overall structure of a shower plan is referenced to determine what subtask to perform, this is episodic control.

Hierarchical control also contributes to everyday tasks that require taking a series of actions in time. Here, one must simultaneously manage a sequence of sub-goals in the context of a superordinate goal. For example (Fig 1B), when taking a shower, people pursue a sequence of sub-goals; like washing their hair, then face, and so forth, all under the temporally abstract overall goal of getting clean (from [10]). Further, each sub-goal must be internally monitored relative to the overall sequential plan because little in the stimulus indicates whether now is the moment to wash one’s hair versus clean one’s face. Thus, sequential tasks often require episodic control wherein a temporal epoch (i.e., episode) serves as the control signal (Fig 1B).

Almost all tasks we do in everyday life have a complex hierarchical structure with multiple levels of goals prevailing over different timescales. Further, structuring a task hierarchically is an effective way to reduce interference among otherwise competing task sets. Indeed, people tend to impose hierarchical structure on tasks even when doing so is unnecessary or costly [11, 12]. So, in the world outside the laboratory, hierarchical cognitive control is likely the representative rather than exceptional case for task performance.

It follows that one’s capacity for hierarchical control may be particularly important for adaptive behavior. In late childhood to early adolescence, age-related differences in rule-guided behavior can be specifically attributed to a developing ability to handle rules with increasing contingencies [9, 13]. Problems with hierarchical control are likewise among the chief complaints of patients with executive function deficits, usually following frontal lobe damage [14–17]. And, these issues often contrast with these same patients’ preserved ability to perform simplified laboratory tests of cognitive control [16, 18, 19]. Further, hierarchical control problems pose theoretical challenges that may not be solved by straightforward extrapolation from simplified tasks and theory (Box 1). Thus, progress requires experiments that explicitly manipulate hierarchical control demands. Experiments of this type have consistently yielded functional differences along the rostro-caudal axis of frontal cortex, an observation that hints at the importance of this organization for this type of complex control.

Is there a Rostro-Caudal Abstraction Gradient in Lateral Frontal Cortex?

Though several variants of a rostro-caudal organizing principle have been proposed (reviewed in [5]), the common element has been that rostral frontal areas support more abstract forms of control than caudal areas. Evidence across species indicates that progress toward the rostral forebrain is marked by change in several anatomical features, including reduced cell density [20, 21], diminished intra-areal connectivity [20], greater dendritic spines [22], decreased laminar differentiation [23, 24], and longer connectional and synaptic distance from sensory input regions [25]. Theorists have long cited these trends to argue that processing becomes more integrative and abstract toward the rostral forebrain.

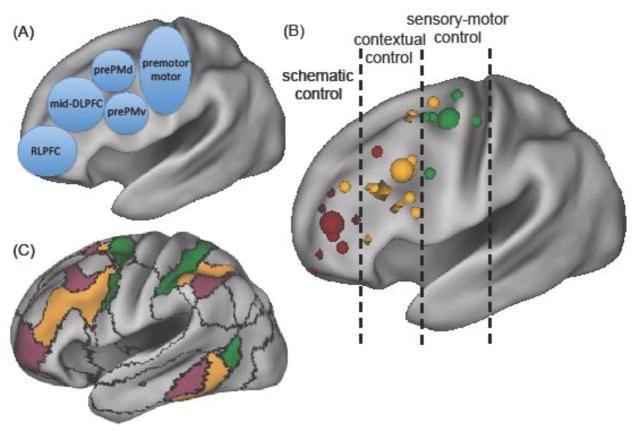

Neuroimaging studies added functional specificity to these foundational ideas [7, 26]. For example, one fMRI study [26] manipulated the abstractness of stimulus-response rules over four levels. At the simplest level, participants responded based on stimulus-response associations (color-finger). Each subsequent level increased the contextual contingencies to be traversed to select a response (color-feature-finger, color-dimension-feature-finger, episode-color-dimension-feature-finger). Activation in progressively rostral prefrontal cortex (PFC) regions tracked competition at higher levels of the task from dorsal premotor (PMd) to anterior premotor (prePM) to mid-dorsolateral PFC (mid-DLPFC) to RLPFC (Fig 2A). Similar abstraction gradients have been observed in studies preceding and following this one [7, 27–35]. These neuroimaging studies gained complementary support from studies of patients with focal brain lesions, who exhibited deficits at a level of complexity commensurate with their lesion and higher, but not lower, levels [36, 37]. Collectively, these data support that more abstract control requires progressively rostral frontal cortex.

Figure 2.

The three zones of rostro-caudal lateral frontal organization. (A) The approximate location of anatomical labels defined in the text on an inflated lateral surface. Dorsal prePM (prePMd) and ventral prePM (prePMv) are separately labeled. (B) Small shapes plot locations of peak foci on the lateral surface from studies that located differences in two or more levels of abstraction. Color distinguishes the three functional zones. Small green spheres plot sensory-motor control (or first order policy). Yellow shapes plot studies manipulating contextual control. Yellow spheres involve 2nd order control. Studies using third order policy are diamonds. Maroon shapes plot studies manipulating schematic control regardless of policy level. Large shapes plot means. The mean sensory motor (Green Sphere: Y=−7) was most caudal. Within the mid-lateral contextual control zone, second and third order control without schematic control demands differed from rostral (third order Yellow Diamond: Y=26) to caudal (second order Yellow Sphere: Y=15). However, regardless of policy, schematic control demands shifted things to most rostral (Maroon sphere: Y=49). (C) The 17-network parcellation of resting state from [76]. Colors highlight the networks that roughly corresponds with the three functional zones: Schematic (Maroon), Contextual (Yellow), and Sensory-Motor (Green).

Testing different forms of abstraction

These early studies provided a foundation of support for the abstraction hypothesis. However, several different types of “abstraction” co-varied in these experiments [5]. As tasks increased in level, contexts generalized over more rules (policy abstraction), more dimensions had to be integrated to make a decision (relational integration), and contexts had to be sustained over longer periods of time while lower-order decisions were made (temporal abstraction). Further, other evidence indicated that anterior frontal areas were more domain general than caudal areas [38, 39], yet a fourth type of abstraction.

Subsequent attempts to distinguish these forms of abstraction from each other have been largely inconclusive. Though several studies have reproduced rostro-caudal differences [27, 29, 34, 35] (Fig 2B), no single type of abstraction has clearly ranked the hierarchy in a task independent way. Further, as tasks have changed, often so have the specific regional associations with different levels of abstraction.

Control over working memory is one task demand that consistently modulates abstraction-related activation patterns. Working memory is central to cognitive control, as it permits the maintenance of task relevant contextual information over time (Box 1). As detailed in Box 2, managing multiple contexts by choosing items to update or select from within working memory may be a central mechanism of hierarchical control. It follows that demands on these processes influence the frontal network. Empirically, however, this influence was first noted in an experiment that pitted different types of abstraction against one another, but failed to find abstraction differences in rostral versus caudal PFC at all [40]. This study used a variant of the 12AX task to distinguish policy versus temporal abstraction. Participants responded according to rules at increasing levels of policy abstraction. Importantly, cues were presented in series so that items could be selectively updated into working memory based on a preceding context.

Box 2. Orchestrating network interactions: Gating and the Striatum.

Cortico-striatal-thalamic circuits may be central in supporting the network interactions required for hierarchical control. Though direct cortico-cortical connections could support these interactions, there are computational advantages to separating mechanisms for memory from those enacting selection and updating, sometimes termed “gating” [101]. A number of models associate the striatum with gating as a means of information routing in complex tasks [102–105].

A gate is a mechanism that regulates propagation from one circuit to another. The cortico-striatal-pallidal-thalamic circuit [106, 107] has long been associated with motor gating [108], acting as a positive or negative feedback loop for cortically represented actions via disinhibition of the thalamus. Neural network models [96] demonstrate that this circuit could also regulate the gating of working memory during cognitive control. For example, the striatum could support an output gate via thalamo-cortical amplification of relevant contexts already maintained in PFC.

Multiple lines of evidence from neuroimaging [33, 41, 109–112], neuropsychology [113], and pharmacological interventions [114–116] support cortico-striatal working memory gating. And, though other mechanisms could also support gating, none has explained the range of memory and learning phenomena that are captured by the cortico-striatal gate.

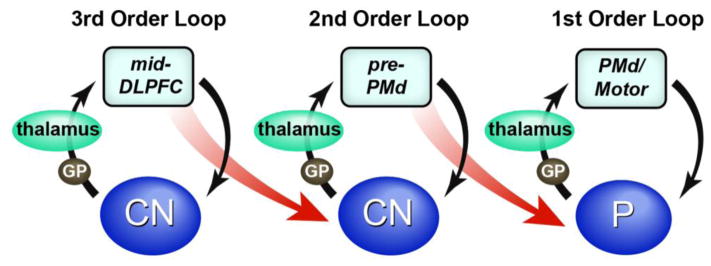

This mechanism can be elaborated to support hierarchical control (Fig II; [94, 109, 117]). For example, higher order context representations in rostral areas could provide top down signals to caudal cortico-striatal loops that regulate output gating of lower order contexts. Indeed, nesting output gating in this way, rather than input gating, may be particularly advantageous for hierarchical control [94, 118].

Fewer studies have directly tested cortico-striatal gating during hierarchical control tasks. One such fMRI study observed that mid-DLPFC increased connectivity with the striatum during input gating of a higher order cortex [33]. However, premotor increased connectivity with parietal cortex rather than striatum when updating the lower order context. A study manipulating both input and output gating similarly found little evidence of cortico-striatal input gating of a lower order context [41]. However, this study did observe evidence of increased prePM-to-caudate connectivity during output gating of the lower order context, perhaps consistent with the emphasis that modeling has placed on output gating during hierarchical control.

There is also preliminary support for multiple interacting cortico-striatal loops. Reward prediction errors related to learning a second order rule modulated fMRI activation in prePMd and a spatially proximate subregion of the caudate nucleus [93]. A study using a hierarchical artificial grammar task [119] showed that three separate pairs of lateral FC and striatal foci were activated by increasing levels of the task, and each shared white matter connections. Further, high fidelity diffusion tractography indicates that not only are fronto-striatal connections finely topographically organized rostro-caudally, but where they diverge from this pattern, they are more likely to do so from rostral PFC to caudal striatum [120], in line with asymmetric top down influences (Fig II).

Cortico-striatal interactions may be crucial for hierarchical control. However, gating mechanisms need not be exclusive to hierarchical control architectures, they could also be applied to unitary context layers. Thus, regardless of the specific architecture, cortico-striatal output gating may be an important part of the mechanism by which hierarchical control is enacted.

Figure II.

Schematic of elaboration of the cortico-striatal model for hierarchical control. Details of the cortico-striatal loops are simplified to emphasize the nested looping structure. Each loop regulates a separate region of frontal cortex. Striatal components of each lower orderloop receive top down context information from higher order areas of FC through diagonal connections (red arrows).

Many areas of the PFC activated to both abstraction manipulations without regional differentiation. Instead, PFC showed stronger transient responses when contextual information was frequently updated, and stronger sustained responses when contexts persisted across trials. The study concluded that the demand to maintain contexts in working memory determined PFC activity rather than abstraction.

This study highlighted how control of working memory, specifically through updating and maintenance, might impact hierarchical control and accordingly, PFC activation patterns. Nevertheless, there were unique features of this experiment that may have contributed to its observations. For example, even lower order policy conditions required referencing temporally remote cues to interpret the present context (i.e., episodic control). Further, as a block design, activity related to individual cues was not assessed.

More recent studies have used similar serial designs while avoiding these limitations. These studies have located results more in line with the rostro-caudal organization, but also confirm the importance of control over working memory. One such fMRI study [33] also employed a 12AX task, but separately examined activation related to updating the higher versus lower order context cue, while minimizing episodic control demands. Updating a lower versus higher order context activated caudal PMd versus rostral mid-DLPFC, respectively. These patterns of activation were further distinguishable from response preparation in motor cortex. Thus, this study observed a clear rostro-caudal pattern related to abstraction, but the specific loci of activation were distinct from similar levels of abstraction tested in previous studies.

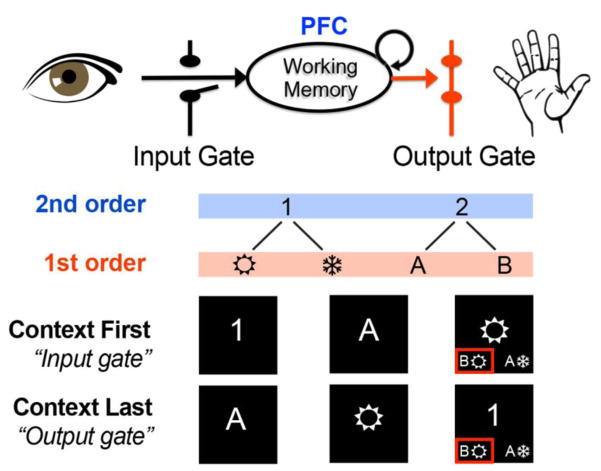

One possible reason for these differences in locus could relate to demands the serial presentation placed on working memory control. Another fMRI study [41] scanned a modified 12AX task in which the higher order context could appear before or after the lower order contextual items (Fig. 3). If the higher order context appeared first, as with [40] and [33], it could be used to update only the relevant lower order context into working memory, a process termed input gating. When the higher order context appeared last, the candidate lower order contexts had to be stored in memory, and then selected once the higher order context appeared, a process termed output gating.

Figure 3.

Gating refers to input and output from working memory. (Top) Updating information into working memory is input gating. Selecting information from within working memory to guide action is output gating. (Bottom) A second order rule from [37] uses a higher order context (number) to decide which lower order context (letter or wingding) is used in a final match decision (red box indicates correct response). The order of second and first order contexts determines gating demands. When a second order context comes first, the relevant first order context can be input gated. When it comes last, the first order context must be output gated from working memory.

More consistent with locations found in previous work [26], this study selectively associated output gating of a second order rule with prePM, rather than areas rostral or caudal. Further, activation in prePM was strongest when the context appeared last versus first. Thus, in contrast to the adaptive maintenance hypothesis [40], it was the demand to use a higher order context to select a lower order context from within working memory that elicited activation in the expected prePM region, not maintenance. Nevertheless, this result also indicates that the dynamics by which contexts are updated and used in working memory will modulate activity patterns in frontal cortex, even when the level of rule abstraction remains constant.

To summarize, demands on working memory gating may be crucial factors in how regions rostral-to-caudal are engaged, over and above manipulations of abstraction. Gates that regulate input and output of working memory are likely important in hierarchical control tasks that require relating separate contextual elements to each other, and so may be core mechanisms of hierarchical cognitive control (see Box 2).

The difficulty with “difficulty”

An important alternative to the abstraction hypothesis is the “difficulty hypothesis”. From this perspective, more rostral frontal cortex is activated as tasks become more difficult. Supporting this view, an fMRI study [42] examined PFC activity while participants identified the shortest among a set of visually-presented lines across conditions that varied in their difficulty. Relative to a baseline, each of the difficulty manipulations increased activity in the PFC as far rostral as the right RLPFC. The mechanisms underlying these manipulations were not specified. Nevertheless, as the difficulty of a perceptual discrimination does not ostensibly vary with abstraction, the authors concluded that PFC is sensitive to task difficulty, not abstraction.

Yet, the difficulty account is hard to reconcile with the broader body of evidence for functional differences along the lateral frontal cortex (Fig 2B). For example, it is unclear why updating a higher order context cue would be more difficult than a lower order response cue, even though the former activates a more rostral site [33]. The fMRI study already discussed that found a rostro-caudal gradient associated with increasingly abstract rules [26] also found that task difficulty, as indexed by response time, could not explain their results. A combined fMRI/transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) study [10] tested a hierarchical sequential task and observed RLPFC to be least activated at the first sequence position, though behaviorally, this position had the longest response time [10, 43]. An fMRI study of effective connectivity during hierarchical control [34] observed RLPFC in their “Delay condition” that required holding a sequence position pending. Though involving episodic control, this was the easiest condition in the experiment based on performance. Thus, though difficulty undoubtedly affects activity in PFC, it is likely the mechanisms that the PFC supports to overcome that difficulty that determines the rostro-caudal activity pattern.

The diverse functions of RLPFC

The function of RLPFC is central to any account of the rostro-caudal organization of PFC. RLPFC has been consistently distinguished from mid-lateral and caudal portions of PFC when some form of episodic or temporally abstract control is required (Fig 2B). RLPFC is active and necessary when participants have to use a temporal context to guide interpretation of the stimulus context [7, 26, 27, 35, 44]. It is also consistently activated when participants hold a pending goal in mind while performing a subtask [30, 34] or prospectively planning a task [45–47].

However, RLPFC activation is also observed under conditions that are not readily described in terms of temporal or episodic control. For example, studies continue to associate RLPFC with relational integration tasks that require integrating multiple stimulus dimensions (e.g., [48]). And, this association is evident even when pitted against maintenance of a (non-integrated) cue over a delay [35].

Further, a growing body of evidence has found RLPFC regions are consistently active when alternative courses of action are merely considered [49]. For example, RLPFC has been associated with strategic choices to explore versus exploit [50–52], such as by tracking the relative uncertainty of an unexplored option [50]. Similarly, RLPFC may track alternative task sets during learning, allowing for new task set discovery [53].

Finally, RLPFC shows a terminal position preference during sequential tasks that is not readily explained as episodic control [54]. In an fMRI experiment [10], participants were required to repeatedly perform two categorization tasks (a color or shape judgment) in a four-task sequence (e.g., color, shape, shape, color). No cues indicated which task to perform on any trial, so the sequence order had to be internally sustained and episodic control was required uniformly throughout. Yet, RLPFC ramped its activation over the course of the task sequence, with its peak activity at the terminal position of the sequence. Others have observed similar terminal position effects during variable length sequences [55]. Further, TMS of RLPFC, but not mid-DLPFC or rostral-medial PFC, induced errors at the end of the sequence [10]. Perhaps relatedly, the sole electrophysiological recording study from monkey frontal pole located strategy-selective cell firing at the end of the trial sequence, during feedback [56].

Thus, broadly, RLPFC appears engaged under conditions requiring abstract superordinate knowledge of current and hypothetical task states, pending states, and future goals; this includes, but is not exclusive to, tasks requiring episodic control.

Beyond gradients: Three frontal cortical zones

In summary, we find limited evidence supporting any single dimension that forms a gradient over lateral frontal cortex, whether that dimension is one particular type of abstraction or global difficulty. However, this is not to say that there are no functional distinctions along the rostro-caudal axis of frontal cortex. On the contrary, the evidence appears to consistently support three major functional subdivisions (Fig 2B).

The most caudal subdivision includes motor and premotor cortex and is generally related to sensory-motor control of effector movements. While movements are commonly considered the output of control processes (i.e. controlled behavior), the ability to sustain working memory may leverage effector systems (e.g. frontal eye-fields for spatial working memory) [57, 58]. Within this zone, motor and premotor subregions hold a hierarchical relationship to one another in the representation of movement[59, 60]. There is also evidence for domain specificity within this zone, such as with respect to spatial versus verbal information along a dorsal/ventral divide [34].

More rostral, the mid-lateral PFC zone is related to contextual control of behavior in the present moment or episode. This zone is associated with diverse task demands, including most conventional cognitive control tasks, and it overlaps the lateral PFC component of the “multiple demand system” [61, 62]. More controversially, within this zone, there may be at least two subregions: prePM and mid-DLPFC [7, 26, 41]. The evidence distinguishing these regions has mostly come from studies manipulating policy abstraction (Fig 2B). This relationship may be due to the demands abstract policy places on working memory gating. However, policy abstraction has not been systematically distinguished from other factors in these areas. For example, there is some evidence that the more caudal subregions are more domain specific than the mid-DLPFC [34]. Nevertheless, these separate areas might provide spatially distinct pools of neurons to support hierarchical control based on separate representations of multiple contexts, above the sensory-motor level (Box 1).

Finally, the most rostral zone includes RLPFC and represents a range of control signals that we term schematic control in order to convey its generality beyond only temporal or episodic signals. Bartlett [63] coined the term schema as a knowledge structure that organizes many lower order features and their relationships. In essence, schemas are models of the world and ourselves in it. Recently, schemas have gained renewed focus in memory systems research [64, 65], where their retrieval and use have been associated with interactions between rostral ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) and hippocampus [64, 66]. Schema representations in vmPFC support knowledge of sequential structure (e.g., [67]), as well as memory-based inferences, such as transitivity among associates [68]. Likewise, vmPFC may represent a “cognitive map” of the latent task space that people can reference to make decisions and learn [69]. Finally, this system has been implicated in episodic future planning, wherein people imagine specific images of future events and goals [70].

RLPFC is consistently engaged when control depends on an episodic or temporally structured context, integration and inference over multiple features, and when tracking hypothetical strategies, goals, and pending states. These types of control broadly depend on the structured information that schemas are proposed to hold. RLPFC also shares close anatomical connections with vmPFC [71, 72], and so it may be well positioned to transmit internal schematic knowledge retrieved by the vmPFC-hippocampal system to the PFC as a control signal. In line with this hypothesis, it was recently observed that the strength of fMRI classifier evidence for a future goal in hippocampus correlated with the strength of activation in RLPFC [73].

The extrinsic connectivity of the frontal lobe largely fits with this functional organization. Evidence from the non-human primate indicates that the PFC can be organized along dorsal and ventral architectonic trends [23, 24], with some also distinguishing a further caudal zone [74] [75]. Five pathways connect the dorsal trend with posterior neocortex and four connect the ventral trend. These pathways transmit uni- and multi-modal information to frontal cortex. Roughly, the primary termination of these sensory pathways tends to be in caudal frontal areas up to area 9/46, with the more rostral areas, like area 46, receiving these inputs indirectly via intrinsic frontal connections or through the cingulate fasciculus. Further, posterior dorsal regions supporting spatial representations, like dorsal parietal cortex, tend to connect with dorsal caudal frontal cortex, while ventral temporal regions processing objects and verbal-semantic information connect with ventral frontal areas. Thus, these connectivity patterns generally align with the observation that caudal areas of PFC are relatively more domain specific and may have closer proximity to the input than rostral ones. However, RLPFC may be similar to these caudal regions in that it shares strong primary connections with vmPFC regions that are important for internally generated schematic knowledge.

This tripartite division between sensory-motor, contextual, and schematic control fits with the heuristic that more rostral areas support more abstract representations. However, these zones are functionally discontinuous, violating a linear, progressive rostro-caudal gradient. Rather, they may overlap with distinct functional networks, such as those identified from a parcellation of resting state functional connectivity [76] (Fig 2C). As such, each zone correlates with distinct areas outside of the lateral frontal cortex, including medial frontal (Box 3), parietal, and temporal lobe structures. Thus, the functional distinctions drawn here may apply to these distributed networks more broadly.

Box 3. A gradient in dorsomedial frontal cortex.

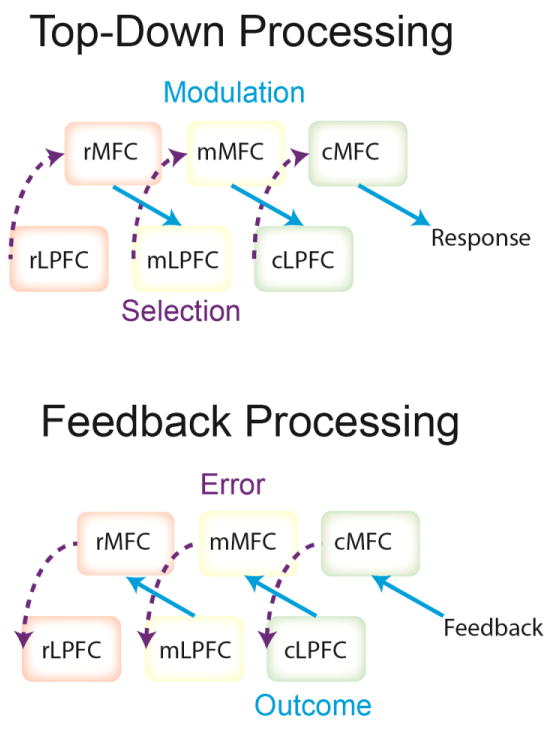

A synergistic role between lateral and dorsomedial PFC has long been a staple of theories of cognitive control. For example, adding a “conflict monitor” to Fig. IA that detects co-activation in the response layer and relays this “response conflict” to the context layer enables dynamic control that simulates trial-by-trial adjustments made in humans [121]. Under this framework, the context layer corresponds to the lateral PFC, while the conflict monitor corresponds to the dorsomedial PFC [122, 123]. More recently, as the lateral PFC has been fractionated into subdivisions, so too has the medial PFC.

Paralleling the lateral PFC, demands on sensory-motor control tend to elicit activity in the caudal supplementary motor area (SMA), while demands on contextual control engage the more rostral preSMA ([124] and dorsomedial PFC. More broadly, gradients along the medial wall have been observed in decision-making contexts, with progressively rostral medial PFC areas computing progressively abstract signals related to competition at the level of responses, decisions, and strategies [125], which have point-by-point interactions with corresponding lateral PFC areas [126, 127].

Dorsomedial PFC areas are particularly sensitive to rewards/penalties [128, 129], with the preSMA showing signals reflecting immediate, contextual incentives, and the more rostral dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) showing signals reflecting tonic, episodic incentives [130]. These dorsomedial PFC signals have been shown to interact with lateral PFC regions sensitive to contextual and episodic control, respectively, and so may provide motivational signals that selectively up-regulate control processes in these lateral PFC zones [130]. Similar point-by-point interactions between the dorsomedial and lateral PFC have been observed when prediction errors require updating of control representations at different levels of abstraction [131]. Collectively, these data indicate a parallel structure between the lateral and dorsomedial PFC.

Numerous modeling efforts have sought to understand the computations performed by the dorsomedial PFC [121, 132–134], but few have attempted to incorporate its rostral-caudal structure. A recent exception is the hierarchical error representation model [132]. Under this model, the fundamental role of dorsomedial PFC is to learn to predict outcomes given the representations retained in the lateral PFC. Distinct medial-lateral layers correspond to first, second, and third order contingencies linking responses to outcomes. Hierarchical control emerges from a cascade of rostral-to-caudal signals whereby rostral dorsomedial PFC areas diagonally influence adjacent caudal lateral PFC areas, modulating representations therein (Fig III). Conversely, performance feedback reverses these dynamics whereby prediction errors update lateral PFC representations and dorsomedial PFC outcome predictions in a caudal-to-rostral manner (Fig III). Collectively, these dynamics allow the model to learn what information is useful to remember to successfully complete complex, hierarchical control problems. The model makes testable predictions of medial-lateral PFC interactions that can guide future research.

Figure III.

Model schematics showing top-down versus feedback processing in the medial-lateral hierarchical architecture from [97].

The processing architecture of lateral frontal cortex

If these distinct zones or networks operate together as a hierarchical control architecture, then there should be evidence that rostral, superordinate regions influence caudal, subordinate regions during hierarchical control tasks [6, 7]. An intracranial recording study in humans [77] provided evidence for such interregional dynamics during hierarchical control. Four patients with implanted subdural grids overlying lateral frontal cortex performed the first three levels of the hierarchical control task previously associated with rostro-caudal differences using fMRI [26]. As the policy level increased, theta-gamma phase-amplitude coupling increased both within PFC and between PFC and premotor/motor electrodes. Further a directional analysis indicated that PFC theta-phase encoding was a stronger predictor of the premotor/motor gamma modulation than the reverse. The precise physiological correlate of these oscillatory signals is still a matter of open research [78, 79]. However, these results provide evidence that hierarchical control demands modulate rostro-to-caudal interregional dynamics.

Of course, a frontal processing hierarchy predicts a deeper, multi-level architecture than was tested in this study. For example, the cascade model [7] proposed that hierarchical control is supported by a propagation of top-down control signals from rostral to caudal areas. RLPFC might form the apex of the frontal hierarchy and would influence mid-DLPFC, which would influence prePM, and so forth toward motor cortex. Support for this model has come from structural equation modeling of fMRI connectivity showing the anticipated top-down cascade, although RLPFC was not explicitly examined. Likewise, an initial review of monkey anatomy suggested that RLPFC might be the apex [80].

Recent evidence, however, has called the idea of an RLPFC apex into question. An extensive meta-analysis of monkey anatomical projections focused on connectional asymmetry. Based on a proposal by [80], any area higher in the hierarchy might exert asymmetrical influence, with broader efferent connections to lower order (i.e., caudal) areas than the reverse. Thus, if it is the apex, RLPFC should show the highest connectional asymmetry. However, among lateral PFC regions, anterior mid-DLPFC (areas 45 and 46) showed the greatest asymmetry, while RLPFC (area 10) was average on this metric [81]. This study did note that a laminar definition of hierarchy [82], rather than connectional asymmetry, would place RLPFC closer to the top. However, effective connectivity from human fMRI has provided convergent evidence that mid-DLPFC, rather than RLPFC, may be the apex of a frontal processing hierarchy.

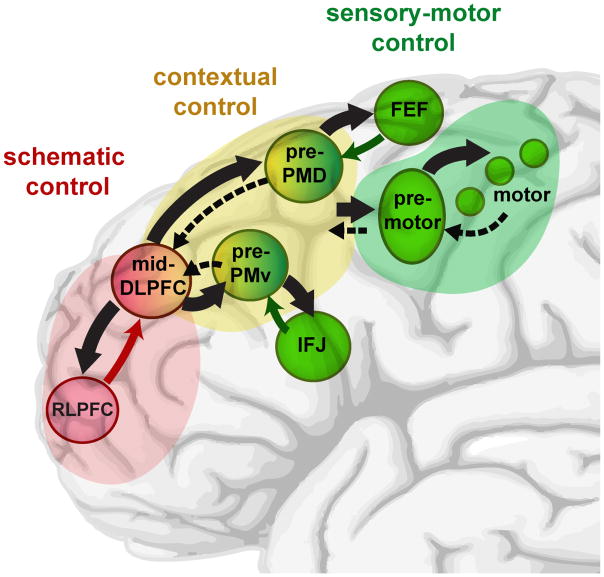

In a recent fMRI study [34], dynamic causal modeling was used to study effective connectivity during a hierarchical control task. Univariate activity dissociated regions along rostral-caudal PFC in accord with the tripartite division we label here as schematic, contextual, and sensory-motor control. A stimulus-domain manipulation identified dorsal (human frontal eye fields [FEF]) and ventral (inferior frontal junction [IFJ]) frontal regions within the caudal sensory-motor zone sensitive to spatial versus verbal information, respectively. Importantly, during periods of minimal cognitive control demands, hierarchical strength, defined again based on greater outward than inward effective connectivity, progressed from a reversed “input” pattern (greater inward than outward connectivity) for the most caudal sensory-motor regions to positive for the caudal mid-lateral regions (prePMv and prePMd) to maximal for rostral mid-DLPFC. However, hierarchical strength then dropped in RLPFC to the reversed (input > output) level, akin to the most caudal sensory-motor regions.

Cognitive control demands modulated these dynamics. The overall pattern was hierarchical such that the apical mid-DLPFC region exerted a domain-general influence on the domain-specific prePMd and prePMv regions. These caudal contextual control regions also received domain-specific input from the sensory-motor regions. Similarly, the mid-DLPFC received input from RLPFC during conditions of schematic control. Collectively, these dynamics demonstrate the integration of inputs from sensory-motor areas (sensory) and RLPFC (schematic), with hierarchical control between mid-DLPFC and prePM. A subsequent fMRI/TMS experiment has replicated these effects and found that behavioral changes following stimulation were consistent with this pattern of information flow [83].

Conclusions: A revised framework for hierarchical control

A longstanding question in the study of cognitive control has concerned whether the fronto-parietal control system is best conceptualized as a unitary controller or if it possesses a meaningful functional organization. This debate has been complicated by further controversy over the “catalogue” of executive functions and their non-specific mapping to regions within this network. The literature reviewed here is inconsistent with any fully unitary view. Likewise, proposals of a unidimensional rostro-caudal gradient of abstraction or processing hierarchy also require revision.

We propose that anterior mid-DLPFC, rather than RLPFC, is the apex of the frontal control hierarchy (Fig. 4). RLPFC is best characterized as a domain specific frontal region, with a role analogous to caudal domain-specific frontal regions. RLPFC’s input domain, however, is internal schema-based knowledge, possibly transmitted from vmPFC and its associated network. When demands on cognitive control arise during a task, sensory information from posterior areas converges with schematic information from RLPFC in the mid-lateral contextual control zone. These regions support cognitive control generally, however the local relationship between mid-DLPFC and prePM, and then premotor and motor cortex within each zone, is hierarchical. Interactions between these areas or networks, as well as their broader outputs to the brain, may be learned and coordinated via gating computations carried out by local cortico-striatal-thalamic loops (Box 2). Motivational, conflict, and/or error signals conveying control demands are tracked via medial frontal cortex, which modulates intensity of control by these lateral frontal zones (Box 3).

Figure 4.

Schematic summary of the functional relationships among regions of frontal cortex. Regions within the schematic (maroon), contextual (yellow), and sensory-motor (green) control zones are labeled along with their respective influences. Heavy, solid black arrows show primary direction of influence, based on structural and effective connectivity. Dashed black arrows show weaker influences. Colored arrows show task-dependent domain specific influences. The architecture features both global and local hierarchical relations, with the contextual control zone influencing the other zones, and then further local hierarchy within the contextual and sensory-motor zones. Individual regions also differ in domain specificity or proximity to different domain influences.

Thus, returning to the examples at the outset of this paper, cases like following complex rules or taking a shower require multiple levels of context to be managed at once. In the present framework, these multiple contextual elements can be updated and maintained separately by different lateral frontal networks running from mid-DLPFC to prePM and premotor to motor cortex, depending on (a) the type of control (sensory-motor or contextual) and (b) the level and domain (verbal/spatial/schematic) of contextual contingency to be monitored. Higher order contingencies are processed more rostrally within these zones. To the degree that control depends on temporal episodes, pending tasks, or future and alternative courses of action, RLPFC may be important for processing and transmitting this information to the control hierarchy, potentially to the highest level in mid-DLPFC. In our example of taking a shower, for instance, RLPFC might track an episodic code that can be referenced as needed to select the correct subgoal at sequence boundaries in the absence of any cues in the environment to do so.

This model subtly contrasts with the perspective of mid-lateral PFC as an amodal hub. Mid-lateral PFC is activated across a range of task demands and may be important in rapidly orchestrating broader network dynamics to perform a diverse range of tasks [62, 84–88]. These observations are not inconsistent with the framework we present here. The overall output from broad contextual control zone could support these diverse demands. Further, due to their placement, caudal prePM areas might be engaged by more tasks.

However, it is important to distinguish that no single area appears to act as an amodal hub. The apical region of mid-DLPFC is not engaged by simple control problems [7, 26, 41]. And, it may not be characterized as a hub in the network sense. Goulas et al. [74] did not find that their apical areas 45 and 46 were hubs as assessed by betweeness centrality (though see [75]). Likewise, most structural connectivity metrics do not assign a particularly high hub score to any mid-lateral PFC region relative to other areas of the frontal lobe [89]. Rather, mid-DLPFC might exert its influence via the other lower-order frontal regions: a hierarchical rather than hub-like network position. More posterior contextual control regions (e.g., prePM) might better resemble hubs in that input from both mid-DLPFC and the caudal sensory-motor regions converge on them [34]. Likewise, as contextual information propagates through the hierarchy, caudal areas lower in the hierarchy might receive a more specific mixture of accumulated contextual information, perhaps consistent with evidence from fMRI multivoxel classifier analysis [90]. However, given their domain sensitivity, they would be expected to be involved variably across different tasks, unlike an amodal hub. Thus, though the overall mid-lateral contextual control zone is perhaps multiple-demand and hub-like when considered as a broad zone, this character may emerge from a local hierarchical processing architecture that changes dynamics among regions in a task-dependent way.

We expect this framework to undergo further revision as we gain new observations regarding the connectivity between networks and regions (see Outstanding Questions Box). It will be important to understand how specific demands, like working memory gating or learning, change these network relationships. And, given the complex tasks required to expose these relationships, more mechanistic theory is needed addressing hierarchical control problems.

Outstanding Questions and Future Directions Box.

How does the brain solve hierarchical control problems? This is the topic of this review, but our review has also made clear that more studies are needed that directly address hierarchical control demands, like policy and temporal abstraction, and the influence of schematic knowledge. Simplified tasks may not expose the dynamics of the control system, whereas complex tasks without clear mechanisms challenge interpretation. More data is needed from hierarchical control tasks with clear operational definitions and interpretable mechanisms.

To what degree do the systems-level dynamics reviewed here generalize across tasks? What is their underlying neurophysiological basis? How do broader cortical and subcortical structures, like the thalamus or parietal cortex, contribute to these dynamics? More studies of anatomical and effective connectivity during hierarchical control tasks are needed, including using approaches beyond fMRI.

What is the relationship between the local hierarchical control structure of frontal cortex and the broader brain networks dynamics required to carry out a task? Recent efforts have applying control and graph theoretic concepts to cognitive control at a systems level may help answer this question.

How do learning and experience impact the hierarchical functional organization of the frontal lobes? There is evidence that the network relationships among frontal regions we review here change with experience. Future studies may inform both the dynamics of this frontal processing architecture, as well as how subcomponents, like striatum, may shape the learning process.

What are the mechanisms of working memory gating? Gating may be central for hierarchical control, but its mechanism – whether cortico-cortical, cortico-striatal-thalamic, or both – remains controversial. Research on the neural dynamics of working memory gating will inform our understanding of hierarchical control and the network dynamics in the system we review here.

In conclusion, research on hierarchical cognitive control prompts departure from both unitary theories and unidimensional abstraction gradients. Rather, the frontal lobes are a dynamic system with several different local networks that interact at a systems level to carry out complex tasks. These networks influence each other through both local and global hierarchical structure, forming a processing architecture capable of enacting complex hierarchically structured rules. This architecture supports our ability to flexibly behave in a complex world.

Trends Box.

It has been proposed that rostral frontal regions support more abstract cognitive control.

Current evidence supports three distinct functional networks supporting sensory-motor control, control based on a present context, and control based on an internal state (schematic control).

However, no single dimension of abstraction defines a gradient across the full rostro-caudal axis of frontal cortex.

The processing architecture of lateral frontal cortex is hierarchical such that some regions influence others more than vice versa.

Mid-DLPFC, not RLPFC, may be the top of the frontal hierarchy.

RLPFC is important for schematic control.

Cortico-striatal circuits may govern hierarchical dynamics among networks.

Motivational signals conveying control demands are tracked via a parallel rostro-caudal organization in medial frontal cortex, which modulates the intensity of control.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH111737, MH099078), a MURI award from the Office of Naval Research (N00014-16-1-2832), and an award from the James S. McDonnell Foundation. We are grateful to Mark D’Esposito, Michael Frank, Christopher Chatham, Theresa Desrochers, Will Alexander, and Apoorva Bhandari for helpful comments and discussions on these topics, and to Charles Badland for help with the illustrations.

Glossary

- Cognitive control

The general capacity to use an internal contextual representation to guide full pathways of thought and action in accord with goals.

- Contextual control zone

Region of mid-lateral PFC supporting cognitive control of thought or action in the present moment or episode based on internally maintained context representations.

- Domain generality

Abstracts over or is insensitive to differences in input domain.

- Episodic control

Using a latent state, episode, or temporal context to guide behavior. The term “episodic” does not imply a necessary relationship to episodic memory, but rather conveys control by episodes or temporal events.

- Hierarchical cognitive control

The specific case whereby context-action relationships are themselves controlled by one or more superordinate contexts.

- Input gate

A mechanism to control what information is encoded and maintained in working memory.

- Output gate

A mechanism to select information from within working memory for further processing.

- Policy

The relationship between a context and an appropriate course of action, akin to a rule.

- Policy abstraction

The degree to which a policy relates contexts to classes of more specific policies.

- Relational integration

The degree to which separate feature dimensions must be related to one another in order to make a decision

- Rostro-caudal organization

The organization of function along a front (rostral) to back (caudal) axis of a brain area.

- Schema

A superordinate declarative knowledge structure that encodes a large number of lower order features and their relationships, abstracted over multiple experiences.

- Schematic controlzone

Region of rostrolateral PFC involved in control based on superordinate or model-based knowledge encoded in schemas.

- Sensory-motor controlzone

Region of caudal frontal cortex involved in control of effector movements based on basic stimulus-response relationships.

- Temporal abstraction

Contexts that are sustained in time and abstract over intervening episodes.

- 12AX task

The standard AX task requires participants to monitor a series of letters for an X that follows an A. The 12AX adds a preceding context, the 1 or 2, that cues whether one monitors for an X following an A or a Y following a B.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Duncan J, et al. Intelligence and the frontal lobe: the organization of goal-directed behavior. Cogn Psychol. 1996;30(3):257–303. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1996.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logan GD, Gordon RD. Executive control of visual attention in dual-task situations. Psychol Rev. 2001;108(2):393–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuss DT, Benson DF. The frontal lobes and control of cognition and memory. In: Perecman E, editor. The Frontal Lobes Revisited. The IRBN Press; 1987. pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badre D. Cognitive control, hierarchy, and the rostro-caudal organization of the frontal lobes. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(5):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuster JM. The prefrontal cortex--an update: time is of the essence. Neuron. 2001;30(2):319–33. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koechlin E, et al. The architecture of cognitive control in the human prefrontal cortex. Science. 2003;302(5648):1181–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1088545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrides M. Lateral prefrontal cortex: architectonic and functional organization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1456):781–95. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amso D, et al. Working memory updating and the development of rule-guided behavior. Cognition. 2014;133(1):201–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desrochers TM, et al. The Necessity of Rostrolateral Prefrontal Cortex for Higher-Level Sequential Behavior. Neuron. 2015;87(6):1357–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins AG, Frank MJ. Cognitive control over learning: creating, clustering, and generalizing task-set structure. Psychol Rev. 2013;120(1):190–229. doi: 10.1037/a0030852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins AGE. The Cost of Structure Learning. J Cogn Neurosci. 2017:1–10. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unger K, et al. Working memory gating mechanisms explain developmental change in rule-guided behavior. Cognition. 2016;155:8–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan J. Disorganization of behaviour after frontal lobe damage. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1986;3(3):271–291. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goel V, et al. Lesions to right prefrontal cortex impair real-world planning through premature commitments. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51(4):713–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shallice T, Burgess PW. Deficits in strategy application following frontal lobe damage in man. Brain. 1991;114(2):727–741. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanini S, et al. Action sequencing deficit following frontal lobe lesion. Neurocase. 2002;8(1–2):88–99. doi: 10.1093/neucas/8.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgess PW, et al. The ecological validity of tests of executive function. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1998;4(6):547–58. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798466037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eslinger PJ, Damasio AR. Severe disturbance of higher cognition after bilateral frontal lobe ablation: patient EVR. Neurology. 1985;35(12):1731–41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.12.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finlay BL. Principles of Network Architecture Emerging from Comparisons of the Cerebral Cortex in Large and Small Brains. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(9):e1002556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiebaut de Schotten M, et al. Rostro-caudal Architecture of the Frontal Lobes in Humans. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27(8):4033–4047. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs B, et al. Regional dendritic and spine variation in human cerebral cortex: a quantitative golgi study. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11(6):558–71. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanides F. Representation of the cerebral cortex and it areal lamination pattern. In: Bourne GH, editor. The Structure and Function of the Nervous System. Academic Press; 1972. pp. 329–453. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeterian EH, et al. The cortical connectivity of the prefrontal cortex in the monkey brain. Cortex. 2012;48(1):58–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margulies DS, et al. Situating the default-mode network along a principal gradient of macroscale cortical organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(44):12574–12579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608282113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badre D, D’Esposito M. Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for a hierarchical organization of the prefrontal cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19(12):2082–2099. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.12.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bahlmann J, et al. The Rostro-Caudal Axis of Frontal Cortex Is Sensitive to the Domain of Stimulus Information. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25(7):1815–26. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbalat G, et al. Impaired hierarchical control within the lateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbalat G, et al. Organization of cognitive control within the lateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(4):377–86. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koechlin E, et al. The role of the anterior prefrontal cortex in human cognition. Nature. 1999;399(6732):148–51. doi: 10.1038/20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koechlin E, Hyafil A. Anterior prefrontal function and the limits of human decision-making. Science. 2007;318(5850):594–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1142995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koechlin E, Jubault T. Broca’s area and the hierarchical organization of human behavior. Neuron. 2006;50(6):963–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nee DE, Brown JW. Dissociable frontal-striatal and frontal-parietal networks involved in updating hierarchical contexts in working memory. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(9):2146–58. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nee DE, D’Esposito M. The hierarchical organization of the lateral prefrontal cortex. Elife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nee DE, et al. Prefrontal cortex organization: dissociating effects of temporal abstraction, relational abstraction, and integration with FMRI. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(9):2377–87. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azuar C, et al. Testing the model of caudo-rostral organization of cognitive control in the human with frontal lesions. Neuroimage. 2014;84:1053–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Badre D, et al. Hierarchical cognitive control deficits following damage to the human frontal lobe. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12(4):515–522. doi: 10.1038/nn.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Courtney SM, et al. Transient and sustained activity in a distributed neural system for human working memory. Nature. 1997;386(6625):608–11. doi: 10.1038/386608a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakai K, Passingham RE. Prefrontal interactions reflect future task operations. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(1):75–81. doi: 10.1038/nn987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reynolds JR, et al. The function and organization of lateral prefrontal cortex: a test of competing hypotheses. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chatham CH, et al. Corticostriatal Output Gating during Selection from Working Memory. Neuron. 2014;81(4):930–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crittenden BM, Duncan J. Task difficulty manipulation reveals multiple demand activity but no frontal lobe hierarchy. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(2):532–40. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider DW, Logan GD. Hierarchical control of cognitive processes: switching tasks in sequences. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2006;135(4):623–40. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.135.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bahlmann J, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation reveals complex cognitive control representations in the rostral frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2015;300:425–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilbert SJ. Decoding the content of delayed intentions. J Neurosci. 2011;31(8):2888–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5336-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Momennejad I, Haynes JD. Human anterior prefrontal cortex encodes the ‘what’ and ‘when’ of future intentions. Neuroimage. 2012;61(1):139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volle E, et al. The role of rostral prefrontal cortex in prospective memory: a voxel-based lesion study. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(8):2185–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parkin BL, et al. Dynamic network mechanisms of relational integration. J Neurosci. 2015;35(20):7660–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4956-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mansouri FA, et al. Managing competing goals - a key role for the frontopolar cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(11):645–657. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Badre D, et al. Rostrolateral prefrontal cortex and individual differences in uncertainty-driven exploration. Neuron. 2012;73(3):595–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boorman ED, et al. How green is the grass on the other side? Frontopolar cortex and the evidence in favor of alternative courses of action. Neuron. 2009;62(5):733–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daw ND, et al. Cortical substrates for exploratory decisions in humans. Nature. 2006;441(7095):876–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donoso M, et al. Human cognition. Foundations of human reasoning in the prefrontal cortex. Science. 2014;344(6191):1481–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1252254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desrochers TM, et al. The Monitoring and Control of Task Sequences in Human and Non-Human Primates. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015;9:185. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Farooqui AA, et al. Hierarchical organization of cognition reflected in distributed frontoparietal activity. J Neurosci. 2012;32(48):17373–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0598-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsujimoto S, et al. Evaluating self-generated decisions in frontal pole cortex of monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(1):120–6. doi: 10.1038/nn.2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nee DE, D’Esposito M. Working Memory. In: Toga AW, editor. Brain Mapping: An Encyclopedic Reference. Academic Press: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 589–595. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buchsbaum BR, D’Esposito M. Short-term and working memory systems. In: Byrne JH, editor. Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference. Adacemic Press; 2008. pp. 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buch ER, et al. A network centered on ventral premotor cortex exerts both facilitatory and inhibitory control over primary motor cortex during action reprogramming. J Neurosci. 2010;30(4):1395–401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4882-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Picard N, Strick PL. Imaging the premotor areas. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11(6):663–72. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(01)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duncan J. The structure of cognition: attentional episodes in mind and brain. Neuron. 2013;80(1):35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fedorenko E, et al. Broad domain generality in focal regions of frontal and parietal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(41):16616–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315235110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bartlett FC. Remembering. Cambridge University Press; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gilboa A, Marlatte H. Neurobiology of Schemas and Schema-Mediated Memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21(8):618–631. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moscovitch M, et al. Episodic Memory and Beyond: The Hippocampus and Neocortex in Transformation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2016;67:105–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghosh VE, et al. Schema representation in patients with ventromedial PFC lesions. J Neurosci. 2014;34(36):12057–70. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0740-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hsieh LT, Ranganath C. Cortical and subcortical contributions to sequence retrieval: Schematic coding of temporal context in the neocortical recollection network. Neuroimage. 2015;121:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeithamova D, et al. Hippocampal and ventral medial prefrontal activation during retrieval-mediated learning supports novel inference. Neuron. 2012;75(1):168–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schuck NW, et al. Human Orbitofrontal Cortex Represents a Cognitive Map of State Space. Neuron. 2016;91(6):1402–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schacter DL, et al. Remembering the past to imagine the future: the prospective brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(9):657–61. doi: 10.1038/nrn2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Averbeck BB, Seo M. The statistical neuroanatomy of frontal networks in the macaque. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4(4):e1000050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Markov NT, et al. A weighted and directed interareal connectivity matrix for macaque cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(1):17–36. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brown TI, et al. Prospective representation of navigational goals in the human hippocampus. Science. 2016;352(6291):1323–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saleem KS, et al. Subdivisions and connectional networks of the lateral prefrontal cortex in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522(7):1641–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.23498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blumenfeld RS, et al. Quantitative Anatomical Evidence for a Dorsoventral and Rostrocaudal Segregation within the Nonhuman Primate Frontal Cortex. J Cogn Neurosci. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yeo BT, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106(3):1125–65. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Voytek B, et al. Oscillatory dynamics coordinating human frontal networks in support of goal maintenance. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(9):1318–24. doi: 10.1038/nn.4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cole SR, Voytek B. Brain Oscillations and the Importance of Waveform Shape. Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones SR. When brain rhythms aren’t ‘rhythmic’: implication for their mechanisms and meaning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2016;40:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Badre D, D’Esposito M. Is the rostro-caudal axis of the frontal lobe hierarchical? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(9):659–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goulas A, et al. Mapping the hierarchical layout of the structural network of the macaque prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(5):1178–94. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barbas H, Rempel-Clower N. Cortical structure predicts the pattern of corticocortical connections. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7(7):635–46. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nee DE, D’Esposito M. Causal evidence for lateral prefrontal cortex dynamics supporting cognitive control. Elife. 2017:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.28040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cole MW, et al. Activity flow over resting-state networks shapes cognitive task activations. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(12):1718–1726. doi: 10.1038/nn.4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cole MW, et al. Multi-task connectivity reveals flexible hubs for adaptive task control. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(9):1348–55. doi: 10.1038/nn.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cole MW, et al. Global connectivity of prefrontal cortex predicts cognitive control and intelligence. J Neurosci. 2012;32(26):8988–99. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0536-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bertolero MA, et al. The modular and integrative functional architecture of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(49):E6798–807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510619112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yeo BT, et al. Functional Specialization and Flexibility in Human Association Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25(10):3654–72. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.van den Heuvel MP, Sporns O. Network hubs in the human brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(12):683–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nee DE, Brown JW. Rostral-caudal gradients of abstraction revealed by multi-variate pattern analysis of working memory. Neuroimage. 2012;63(3):1285–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cohen JD, et al. On the control of automatic processes: A parallel distributed processing account of the Stroop effect. Psychological Review. 1990;97:332–361. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ranti C, et al. Parallel temporal dynamics in hierarchical cognitive control. Cognition. 2015;142:205–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Badre D, Frank MJ. Mechanisms of hierarchical reinforcement learning in cortico-striatal circuits 2: evidence from fMRI. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(3):527–36. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Frank MJ, Badre D. Mechanisms of hierarchical reinforcement learning in corticostriatal circuits 1: computational analysis. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(3):509–26. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Badre D, et al. Frontal cortex and the discovery of abstract action rules. Neuron. 2010;66(2):315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.O’Reilly RC, Frank MJ. Making working memory work: a computational model of learning in the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia. Neural Comput. 2006;18(2):283–328. doi: 10.1162/089976606775093909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Alexander WH, Brown JW. Hierarchical Error Representation: A Computational Model of Anterior Cingulate and Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex. Neural Comput. 2015;27(11):2354–410. doi: 10.1162/NECO_a_00779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rigotti M, et al. The importance of mixed selectivity in complex cognitive tasks. Nature. 2013;497(7451):585–90. doi: 10.1038/nature12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fusi S, et al. Why neurons mix: high dimensionality for higher cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2016;37:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Song HF, et al. Training Excitatory-Inhibitory Recurrent Neural Networks for Cognitive Tasks: A Simple and Flexible Framework. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(2):e1004792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–80. doi: 10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Frank MJ, O’Reilly RC. A mechanistic account of striatal dopamine function in human cognition: psychopharmacological studies with cabergoline and haloperidol. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120(3):497–517. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Helie S, et al. A neurocomputational model of automatic sequence production. J Cogn Neurosci. 2015;27(7):1412–26. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kriete T, et al. Indirection and symbol-like processing in the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(41):16390–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303547110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]