Abstract

Although the number of clinical applications for fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) cardiac positron emission tomography (PET) has continued to grow, there remains a lack of consensus regarding the ideal method of suppressing normal myocardial glucose utilization for image optimization. This review describes various patient preparation protocols that have been used as well as the success rates achieved in different studies. Collectively, the available literature supports using a high-fat, no-carbohydrate diet for at least two meals with a fast of 4–12 hours prior to 18F-FDG PET imaging and suggests that isolated fasting for less than 12 hours and supplementation with food or drink just prior to imaging should be avoided. Each institution should adopt a protocol and continuously monitor its effectiveness with a goal to achieve adequate myocardial suppression in greater than 80% of patients.

Keywords: PET imaging, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), metabolism, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac positron emission tomography (PET) using fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) has demonstrated utility in the identification and treatment of disease processes that involve pathologic inflammation within the heart.1 Current applications include imaging intra-cardiac device and prosthetic valve infections,2,3 evaluating patients with known or suspected cardiac sarcoidosis or other inflammatory cardiomyopathies,4–6 and an emerging potential role in identification of vulnerable coronary artery plaques.7,8 A challenge faced by this imaging technique is optimizing its ability to distinguish focal areas of pathological 18F-FDG uptake from normal physiologic myocardial uptake.

A number of preparations have been described to suppress 18F-FDG uptake by the myocardium, but there is no consensus on the optimal method and limited data comparing different approaches. Comparison is further limited by the significant variability in protocols used in different studies and by different institutions. This article seeks to review and compare the effectiveness of different preparations and to provide some practical recommendations about methods of suppressing physiologic myocardial glucose uptake for PET imaging based on existing data.

MYOCARDIAL METABOLISM

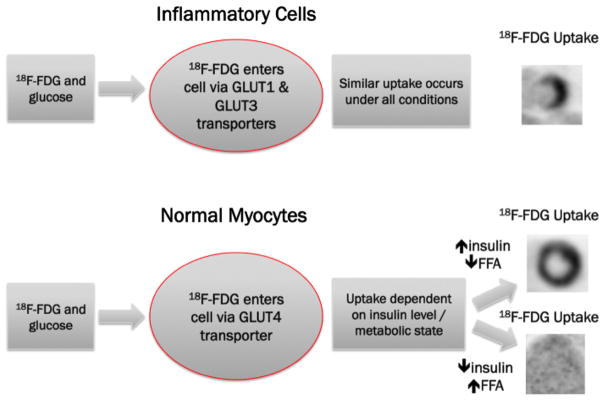

Because normal myocardium has a variable avidity for glucose, and hence 18F-FDG, preparation to promote free fatty acid metabolism and suppress physiologic glucose metabolism is necessary for successful PET 18F-FDG imaging of pathologic processes in the heart. Dietary carbohydrate intake normally triggers insulin secretion, which activates the predominantly expressed glucose transporter GLUT4 in normal myocardium and allows glucose to enter cells. In the absence of carbohydrates and insulin, the myocardium uses free fatty acids for energy.9 However, in inflammatory cells, glucose enters the cell via GLUT1 and GLUT3 (which are constitutively expressed).10 After entering a cell via a glucose transporter, 18F-FDG is trapped by phosphorylation, allowing for metabolic imaging.11 As such, active inflammation or granulomatous disease may be identified by 18F-FDG in an atmosphere that optimally suppresses physiological myocardial uptake of 18F-FDG, as illustrated in Figure 1.12,13 In contrast, when using 18F-FDG imaging to assess myocardial viability, a high insulin state is preferred to promote glucose utilization by hibernating myocardium.14 In such cases, 18F-FDG imaging takes advantage of the upregulation of glucose transporters in ischemic and hibernating myocardium.15

Figure 1.

A schematic demonstrating glucose utilization by inflammatory cells and normal myocardium under variable metabolic conditions.

REVIEW METHODS

A comprehensive literature review was performed to identify studies describing preparation to reduce physiological myocardial glucose utilization for cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging. Studies completed prior to December 2015 with at least nine patients undergoing each method of dietary preparation and a description of the quality of myocardial 18F-FDG uptake suppression were included in this review. Studies that included patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis that did not report the prevalence of sarcoidosis or included a majority (>50%) of patients with known sarcoidosis were excluded to minimize the potential bias of categorizing non-specific 18F-FDG uptake as pathologic. This may occur because there is an increased index of suspicion for active disease in populations that have a higher prevalence of known sarcoidosis. For example, focal-on-diffuse 18F-FDG uptake could be interpreted as positive for inflammation or inadequate suppression in varying clinical situations.

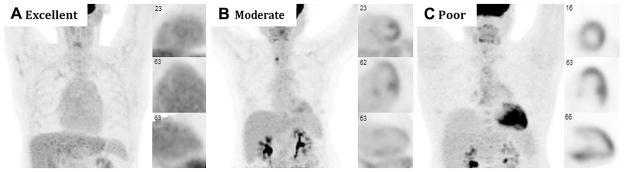

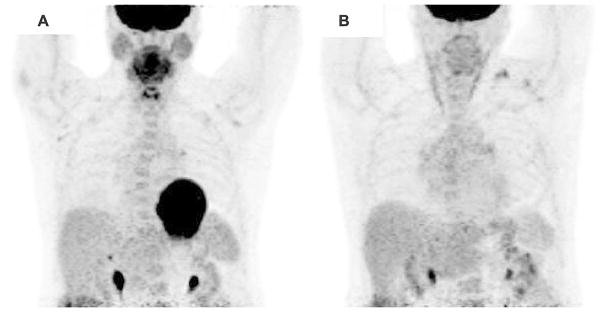

For the purposes of this article, adequate suppression was defined as myocardial uptake that was equal to or less than that seen in the liver in the studies that reported this information or as otherwise defined by each individual study. Only studies that included an assessment of the suppression of physiological glucose utilization by the entire myocardium were included. Figure 2 demonstrates example images of complete, moderate, and poor suppression of physiological myocardial 18F-FDG uptake. Figure 3 shows the results of two separate cardiac 18F-FDG PET scans for the same patient with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. The first image shows diffuse myocardial uptake of 18F-FDG suggesting poor suppression of physiological glucose utilization, likely due to non-compliance with the prescribed dietary preparation. The second shows excellent suppression of physiological glucose utilization, likely indicating excellent compliance with dietary preparation.

Figure 2.

Cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging demonstrating variable suppression in three patients without cardiac disease: A excellent myocardial suppression with blood pool activity that exceeds that of the myocardium, B moderate myocardial suppression with diffuse low-level myocardial 18F-FDG uptake and non-specific focally increased uptake in the papillary muscles and lateral wall, and C poor myocardial suppression with diffuse 18F-FDG uptake throughout the heart.

Figure 3.

Cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging of a patient with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis with A poor myocardial suppression following non-compliance with 4 hour fast prior to 18F-FDG imaging and B excellent suppression following appropriate dietary preparation and fasting demonstrating no focal 18F-FDG uptake.

Ultimately, fifteen studies met the stated criteria for inclusion in this review. For each of these studies, data pertaining to the preparation strategies utilized, total number of patients, and number of patients with adequate physiologic suppression were collected. Where available, the serum blood glucose values, free fatty acid levels, and insulin levels were extracted (Table 1). Analyses comparing the effectiveness of various preparations were similarly reviewed.

Table 1.

Mean glucose, free fatty acid, and insulin levels with different preparations

| First author | Preparation | Blood glucose (mg/dL) | Free fatty acid (mEq/L) | Insulin (μU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wykrzykowska8 | HFLC meal with high-fat (vegetable oil) drink prior to test | 99 ± 43 | ||

| > 8 hour fast | 109 ± 32 (NS) | |||

| Harisankar17 | HFLC diet and 6 hour fast | 96 | ||

| > 12 hour fast | 94 (NS) | |||

| Kumar22 | 4–6 hour fast | 117 ± 21 | ||

| 12–14 hour fast | 101 ± 17 | |||

| HFLC diet and overnight fast | 98 ± 26 (NS) | |||

| Coulden23 | LC diet (< 3 g) 24 hours before with > 8 hour fast | 94.7 ± 11.9 | ||

| > 8 hour fast | 107.3 ± 15.5 (NS) | |||

| Lum25 | No-carbohydrate meal with 12 hour fast | 87.4 ± 21.3 | ||

| 12 hour fast | 87.5 ± 10.6 (NS) | |||

| Morooka5 | ~18 hour fast | 85.1 ± 11.0 | 0.64 ± 0.24 | |

| 12 hour fast with 50 IU/kg IV heparin | 99.1 ± 7.8 (P < .0001) | 0.64 ± 0.27 (NS) | ||

| Manabe6 | LC diet with 18 hour fast with 50 IU/kg IV heparin | 84.3 ± 11.1 | 2.12 ± 0.53 | 2.88 ± 3.67 |

| > 6 hour fast with 50 IU/kg IV heparin | 93.3 ± 15.2 (P = .01) | 2.03 ± 0.71 (NS) | 4.47 ± 2.38 (P < .0001) |

Values displayed as mean ± standard deviation. NS non-significant

A meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of myocardial suppression was not pursued due to the significant heterogeneity in methods of preparation reported. Additionally, a meta-analysis was recently performed to examine the association of various patient preparation techniques with the diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET for cardiac sarcoidosis, as detailed below.16

METHODS OF SUPPRESSING PHYSIOLOGICAL MYOCARDIAL 18F-FDG UPTAKE

Several methods of patient preparation have been described and evaluated in the literature (Table 2). Many of these preparations have been developed on the basis of institutional experiences and preferences and the ability to reliably convey and implement these protocols for a given patient population.

Table 2.

Preparation strategies and metabolic consequences

| Common preparation | Metabolic effects |

|---|---|

| High-fat, no-carbohydrate (HFNC) diet4,18 |

|

| High-fat, low-carbohydrate (HFLC) diet7,8,17,19,22 |

|

| Low-carbohydrate diet6,19–21,23–25 |

|

| Short- to long-term fasting4–7,17–20,22–26 |

|

| Co-administration of high-fat beverage prior to exam7,8,19,20 |

|

| Co-administration of verapamil7 |

|

| Co-administration of heparin5,6,24 |

|

Behavioral Approaches

Vigorous exercise and the resulting catecholaminergic stimulation increase myocardial glucose uptake by augmenting transporter recruitment and glucose utilization via oxidation.9 As a result, almost all strategies urge patients to avoid strenuous exercise for 12–24 hours prior to their exam.

Dietary Approaches

One well-studied strategy is to utilize a high-fat and low- or no-carbohydrate (HFLC or HFNC) diet in preparation for myocardial 18F-FDG PET imaging. In these studies, patients are instructed to eat at least one fatty meal prior to the exam with minimal or no carbohydrates with a subsequent fast prior to 18F-FDG administration. In addition to suppressing insulin release, this strategy also aims to increase serum fatty acids for myocardial utilization.4,7,8,17–19,22 Prescribed high-fat diets were reported to contain 20–35 g of fat.18,19 The effect of adding a high-fat drink to this diet just prior to giving 18F-FDG in an attempt to further augment serum fatty acid levels has also been evaluated.7,8,19,20 One study examined the role of using a low-carbohydrate diet for one full day with comparison to an unrestricted diet.21

Alternatively, other studies have described the use of fasting as a means of shifting cardiac metabolism toward free fatty acids and away from glucose prior to 18F-FDG administration.4–7,17–20,22–26 This strategy also reduces insulin release and promotes systemic lipolysis, both of which suppress myocardial glucose utilization. The optimal duration of fasting is unknown, and a range (e.g., 4–18 hours) of durations has been assessed.

Pharmacologic Approaches

Pharmacologic strategies have also been employed with the aim of manipulating myocardial metabolism. Intravenous heparin administration, which promotes lipolysis and the availability of free fatty acids,27 has been described as a means of augmenting a dietary preparation.5,6,24 Intracellular calcium is known to increase glucose uptake, and calcium channel blockade has reduced myocardial 18F-FDG uptake in a mouse model.28 As such, one study has explored the use of calcium channel blockade with verapamil as a means of improving myocardial suppression.7

Most studies have combined two or more of these strategies to achieve optimal myocardial suppression. These strategies have included a prescribed meal prior to a prolonged fast or the addition of a pharmacologic adjunct to a dietary preparation or prolonged fast and are detailed below.

PRIOR META-ANALYSIS OF PREPARATION FOR 18F-FDG PET FOR CARDIAC SARCOIDOSIS

A recent meta-analysis of 16 studies and 559 patients referred for cardiac 18F-FDG PET for suspected or known cardiac sarcoidosis by Tang et al. sought to examine how different patient preparations may impact the sensitivity and specificity of 18F-FDG PET for the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. It was concluded that fasting duration and heparin administration significantly affected the diagnostic odds ratio (P = .01 and .04, respectively), but a HFLC diet did not have a significant effect (P = .17).16

This study and its findings are limited by the fact that there is no reliable reference standard on which to base these diagnostic accuracy parameters for cardiac sarcoidosis. Tang et al. used the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare Criteria in their analysis;29,30 however, many prior studies have shown that imaging is more sensitive and specific than these clinical criteria.4,30,31 Furthermore, because most studies were small and preparation strategies were heterogeneous, there was insufficient power to determine if one specific technique results in superior diagnostic accuracy. Finally, the analysis only included studies that contained patients with known or suspected cardiac sarcoidosis rather than a broader patient population.

EFFICACY OF SUPPRESSION OF PHYSIOLOGICAL MYOCARDIAL 18F-FDG UPTAKE

Although there was a great deal of variability in the specific protocols used for dietary preparation, there was a substantial overlap in the general methods employed by these studies. Several studies reported the efficacy of a specific protocol used at an individual institution, while others systematically compared the effectiveness of different strategies. The results of these preparations are listed in Table 3, and each study is described individually in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 3.

Variability in methods and adequacy of myocardial suppression

| Preparation | Adequate | Total patients | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-fat, no-carbohydrate diet for two meals with 4 hour fast4 | 103 | 118 | 87 |

| High-fat, no-carbohydrate diet for two meals with 4 hour fast18 | 28 | 30 | 93 |

| High-fat, low-carbohydrate diet for two meals with 4 hour fast17 | 54 | 60 | 90 |

| High-fat, low-carbohydrate meal with 18 hour fast7 | 8 | 9 | 89 |

| High-fat, low-carbohydrate diet for 2 days with 12–14 hour fast22 | 39 | 51 | 76 |

| Low-carbohydrate meal with fast of at least 12 hour19 | 17 | 21 | 81 |

| Low-carbohydrate diet for 24 hours prior to > 8 hour fast23 | 92 | 94 | 98 |

| Low-carbohydrate meal with 12 hour fast24 | 27 | 50 | 54 |

| No-carbohydrate meal with 12 hour fast25 | 35 | 47 | 74 |

| High-fat, low-carbohydrate meal with 12 hour fast and verapamil7 | 8 | 9 | 89 |

| Low-carbohydrate meal with 18 hour fast and heparin6 | 24 | 24 | 100 |

| Low-carbohydrate meal with 12 hour fast and heparin24 | 44 | 50 | 88 |

| Low-carbohydrate diet for 24 hours21 | 68 | 100 | 68 |

| Low-carbohydrate diet for 24 hours with high-fat beverage20 | 10 | 14 | 71 |

| High-fat, low-carbohydrate meal with high-fat beverage19 | 12 | 21 | 57 |

| High-fat, low-carbohydrate meal with high-fat beverage/olive oil7 | 9 | 18 | 50 |

| High-fat, low-carbohydrate meal with high-fat beverage8 | 20 | 32 | 63 |

| 4–6 hour fast22 | 5 | 51 | 10 |

| 6 hour fast24 | 14 | 50 | 28 |

| > 6 hour fast20 | 4 | 14 | 29 |

| ~6 hour fast26 | 14 | 36 | 39 |

| > 8 hour fast23 | 80 | 120 | 67 |

| 12–14 hour fast22 | 28 | 51 | 55 |

| > 12 hour fast17 | 27 | 50 | 54 |

| ~12 hour fast26 | 30 | 66 | 45 |

| 12 hour fast25 | 14 | 49 | 29 |

| ~18 hour fast5 | 12 | 18 | 67 |

| Heparin bolus after > 6 hour fast6 | 42 | 58 | 72 |

| Heparin bolus after 12 hour fast5 | 2 | 19 | 11 |

| Unrestricted diet19 | 13 | 21 | 62 |

| Unrestricted diet21 | 15 | 100 | 15 |

Table 4.

Studies comparing multiple methods of myocardial suppression

| First author | Preparation comparison | Population | Protocol | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morooka5 | ~18 hour fast (N = 19) vs 12 hour fast with heparin (N = 18) | Normal (subgroup) |

|

|

| Manabe6 | LC diet with 18 hour fast with heparin load (N = 24) vs > 6 hour fast with heparin load (N = 58) | Suspected CS |

|

|

| Demeure7 | HFLC meal/12 hour fast (group 1) vs HFLC meal/12 hour fast/supplemental HF drink (group 2) vs HFLC meal/12 hour fast/supplemental olive oil (group 3) vs HFLC meal/12 hour fast/verapamil (group 4) | Normal |

|

|

| Harisankar17 | HFLC diet/fast (N = 60) vs > 12 hour fast (N = 50) | Oncologic (N = 119) and suspected CS (N = 1) |

|

|

| Cheng19 | Unrestricted (group 1, N = 21) vs LC (group 2, N = 21) vs HFLC with supplemental HF drink 1 hour before imaging (group 3, N = 21) | Oncologic |

|

|

| Kobayashi20 | LC diet (< 10 g glucose, N = 14) and HFLC drink vs greater than 6 hour fast (N = 14) | Normal |

|

|

| Balink21 | LC diet (N = 100) vs unrestricted diet (N = 100) | Oncologic |

|

|

| Kumar22 | 4–6 hour fast (group 1, N = 51) vs 12–14 hour fast (group 2, N = 51) vs HFLC diet and > 12 hour fast (group 3, N = 51) | Oncologic without known coronary artery disease |

|

|

| Coulden23 | LC diet (< 3 g) day before/overnight fast (N = 94) vs overnight fast (N = 120) | Oncologic |

|

|

| Scholtens24 | 6 hour fast (group 1, N = 50) vs LC diet + 12 hour fast (group 2, N = 50) vs LC diet + 12 hour fast + heparin (group 3, N = 50) | Group 1: oncologic Group 2–3: Inflammation or infection |

|

|

| Lum25 | Carbohydrate meal + 12 hour fast (N = 49) vs non-carbohydrate meal + 12 hour fast (N = 47) | Oncology |

|

|

| Lee26 | Overnight (~12 hour, N = 66) vs non-overnight (~6 hour, N = 36) fast | Normal |

|

|

Table 5.

Studies evaluating myocardial suppression in a single cohort

| First author | Preparation | Population | Protocol | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blankstein4 | HFNC diet with brief fast (N = 118) | Suspected cardiac sarcoidosis |

|

|

| Wykrzykowska8 | HFLC meal with high-fat (vegetable oil) drink prior to test (N = 32) | Oncologic |

|

|

| Soussan18 | Two HFNC meals with 4 hour fast | Oncologic (N = 30) |

|

|

Three randomized studies have been performed. Cheng et al. compared preparation in groups of 21 patients with an unrestricted diet, a HFLC meal and subsequent fast of approximately 12 hours, and a HFLC meal with a high-fat drink 1 hour prior to the exam with findings of significantly improved suppression with a HFLC diet and fast over the other strategies (57% vs 81% vs 62% success).19 Demeure et al. compared the effectiveness of four different approaches: a HFLC meal followed by a 12 hour fast, HFLC meal followed by a high-fat drink or olive oil 1 hour prior to imaging, and a HFLC meal followed by 12 hour fast and oral verapamil. Their study included groups of nine patients. It found improved suppression in the HFLC meal followed by 12 hour fast group over the HFLC meal together with a drink or olive oil group (89% vs 50%) and similar suppression with the addition of verapamil to the HFLC and 12 hour fast preparation (89% vs 89%). They concluded that a HFLC diet with 12 hour fast with or without verapamil had a trend toward better suppression, but there was no significant difference.7 Another article evaluated a HFLC diet for 2 days and subsequent 12–14 hour fast with a 12–14 hour fast alone in groups of 51 patients and found that HFLC improved the rate of suppression (76% vs 55%).22

In addition, there have been a number of non-randomized studies. In one study, 60 patients underwent preparation with two HFLC meals and a 4 hour fast, and 50 patients were prepared with a greater than 12 hour fast with significantly improved suppression in the HFLC group (90% vs 54% success).17 Manabe et al. assessed a brief fast of more than 6 hours followed by intravenous heparin prior to imaging in comparison to a LC meal with an 18 hour fast and heparin administration and found improved efficacy in the latter (72% vs 100%).6 Kobayashi et al. demonstrated that a LC diet bolstered by a high-fat drink led to complete suppression in 71% of patients as compared to 29% of patients prepared with a greater than 6 hour fast alone. In this study, patients prepared with a diet who had focal uptake were frequently noted to have uptake in the papillary muscles.20 A 24 hour dietary preparation with a fat-allowed, low-carbohydrate diet was shown to be superior to unrestricted preparation with 68% vs 15% suppression.21 Likewise, a 24 hour dietary preparation with <3 g of carbohydrates and >8 hour fast (98%) led to improved myocardial suppression over a fast alone (67%) in oncologic patients.23 A long-term fast of approximately 18 hours was compared to a 12 hour fast with adjunctive heparin administration in subgroups of 18 and 19 healthy patients, respectively, with a higher rate of suppression in the group with a longer duration of fasting (67% vs 12%). Common patterns of non-specific 18F-FDG uptake involved the basal ring and lateral wall.5 A recent study reviewed 150 cardiac 18F-FDG PET images at a single institution with three groups of 50 patients prepared with either a 6 hour fast, a low carbohydrate diet with a 12 hour fast, or a low carbohydrate diet followed by a 12 hour fast and heparin bolus had successful suppression in 28%, 54%, and 88% of those in the respective groups. Significantly improved suppression was noted in the final group as compared to fasting alone. In this study, normal variants included uptake in the basal myocardial ring and lateral wall.24 The addition of a carbohydrate restricted meal prior to a 12 hour fast outperformed a 12 hour fast by itself with suppression in 74% and 29% of oncology patients, respectively.25 In a study by Lee et al., a short-term fast of approximately 6 hours in 36 patients was compared with a longer fast of above 12 hours in 66 patients with findings of adequate suppression in 14 (39%) and 30 (45%) of the subjects.26

A final group of studies exploring applications of cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging reported suppression rates with a standardized protocol used throughout the study. Blankstein et al. employed a preparation consisting of HFNC dinner and breakfast followed by a fast of at least 4 hours in a population of 118 patients undergoing evaluation for sarcoidosis with successful suppression in 103 patients (87%).4 In a study utilizing cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging to detect metabolically active coronary plaques, a protocol of a HFLC meal followed by a high-fat drink was effective in 20 of 32 patients (63%).8 In another publication, 30 control patients were prepared with a HFLC diet for two meals with a 4 hour fast preceding their imaging with adequate suppression seen in 28 patients (93%), though focal papillary muscle uptake was noted in five of the subjects with adequate suppression. In this study, patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis were assessed separately; however, the frequency of adequate suppression was not reported, and their results were not included.18

DISCUSSION

While there has been a high degree of variation in the protocols described in these studies, there are general trends that support certain principles for effective preparation for myocardial suppression to optimize cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging. Current SNMMI/ASNC/SCCT guidelines recommend preparation with a diet rich in fat and devoid of carbohydrates for 12–24 hours prior to the scan, a 12–18 hour fast, and/or the use of intravenous heparin approximately 15 min prior to 18F-FDG injection.32 The reviewed data suggest that a HFNC diet should be implemented for one or two meals with a subsequent fast of at least 4 hours, although an even longer fast may be preferred for optimal suppression of myocardial glucose uptake. With this strategy, successful suppression has been demonstrated in up to 85–90% of patient populations in most studies,4,17,18 although other studies have reported lower rates of adequacy using this strategy.22 Another effective strategy appears to be a no or low carbohydrate meal, followed by a fast and heparin administration just prior to 18F-FDG administration. Two studies have demonstrated adequate suppression with this strategy in 88–100% of patients.6,24

Several strategies have demonstrated limited benefit for imaging preparation. For instance, it does not appear that verapamil administration provides added benefit.7 Short-term fasting without any dietary preparation appears to provide the lowest rate of suppression, especially with durations of 6 hours or less.20,22,24,26 Multiple studies have revealed no benefit or diminishing success with the addition of a high-fat drink within an hour prior to the scan.7,8,19,20 These findings support the notion that fat loading immediately prior to imaging could be disadvantageous and may paradoxically cause increased 18F-FDG uptake by increasing myocardial oxygen consumption and glucose metabolism.33

An ideal preparation strategy for cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging would facilitate complete suppression of physiologic 18F-FDG uptake by normal myocardium. Nevertheless, the included studies did not always report complete suppression. In fact, multiple studies determined adequacy of suppression by semi-quantitative grading comparing cardiac to hepatic uptake or by quantifying the intensity of myocardial uptake in relation to a threshold value. In the current review, each individual study had a unique definition for adequacy, which rarely required complete suppression of 18F-FDG uptake (i.e., the optimal definition of adequate). The definitions of adequacy for each study are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

The Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare (JMHW) has established clinical criteria for the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and is relied upon as the standard for diagnosis of the disease;29,30 however, as previously mentioned, the validity and predictive value of these criteria have been called into question by several articles.4,30,31 Given that there is not a true diagnostic gold standard for cardiac sarcoidosis, this article did not seek to determine the diagnostic accuracy of cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging for cardiac sarcoidosis. Additionally, given the significant variation of patient populations and preparations in the reviewed studies, it was felt that it was not possible to meaningfully pool the studies to provide any summary statistics.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the reviewed literature, we advocate for the use of at least two HFNC meals followed by a fast of at least four hours as the most effective preparation for cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging of inflammation. Intravenous heparin, when administered just prior to imaging following at least one HFLC meal and overnight fast, appears to be part of a regimen that is as efficacious as two HFNC meals with a fast but requires exposure to an intravenous medication with possible adverse reactions. We do not recommend preparation plans that utilize fasting alone; however, when such an option has to be employed, i.e., a patient who cannot eat or has dietary restrictions precluding the recommend diet, fasting for at least 18 hours is suggested. We also do not advocate the use of calcium channel blockers or unrestricted diets. Likewise, patients should be instructed to avoid eating or drinking anything within at least 4 hours of their test, and a high-fat supplement given during this interval immediately prior to the exam does not appear to have additive benefit. Exercise should be avoided for 24 hours prior to the exam. These recommendations are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Recommendations

| Recommendation | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Favorable evidence | Utilize HFNC diet for at least two meals |

| Fast of at least 4 hours duration prior to exam | |

| Avoid carbohydrate intake | |

| Optimize fat intake | |

| Avoid vigorous exercise within 24 hours of the exam | |

| Continuous review of rate of suppression for all cardiac 18F-FDG PET studies with a goal of 80% adequacy | |

| Maybe | Heparin given intravenously 15 min before 18F-FDG with dietary preparation/fasting |

| Inadequate evidence | Any food or drink within 4 hours of exam |

| Unrestricted diet | |

| Isolated fasting (< 12 hours) | |

| Calcium channel blockers |

Special caution should be taken in inpatient studies. It is critical to avoid the use of intravenous medications that contain dextrose within 12 hours of imaging. Likewise, there must be communication between nurses, physicians, nutritionists, kitchen staff, and the patient to avoid inadvertent errors in preparation. Specific dietary instructions are included in Table 7.

Table 7.

Specific dietary recommendations

| Consume | Meat fried in oil or butter without breading or broiled (chicken, turkey, bacon, meat-only sausage, hamburgers, steak, fish) |

| Eggs (prepared without milk or cheese) | |

| Oil (an option for patients who are unable to eat and have enteral access or vegan patients) and butter | |

| Clear liquids (water, tea, coffee, diet sodas, etc.) | |

| Acceptable | Some artificial sweeteners (Sweet’N Low, Equal, NutraSweet) |

| Fast of 18 hours or longer if unable to eat with no enteral access or dietary restrictions preventing consumption of advised diet | |

| Avoid | Vegetables, beans, nuts, fruits and juices |

| Bread, grain, rice, pasta, all baked goods | |

| Sweetened, grilled or cured meats or meat with carbohydrate-containing additives (some sausages, ham, sweetened bacon) | |

| Dairy products aside from butter (milk, cheese, etc.) | |

| Candy, gum, lozenges and sugar | |

| Alcoholic beverages, soda and sports drinks | |

| Mayonnaise, ketchup, tartar sauce, mustard and other condiments | |

| Dextrose containing intravenous medications |

Recognizing that currently available data do not point to a single preparation technique as markedly superior to all others and that individual patients have variable metabolic profiles, we believe it is prudent for different centers to optimize unique protocols that adhere to the above principles. We recommend that every center continuously review the quality of achieved background suppression for all cardiac 18F-FDG PET studies. In general, by following the above principles, adequate suppression, defined as complete suppression of myocardial physiologic glucose uptake or suppression sufficient for diagnostic evaluation, should be achieved in greater than 80% of studies. Additional high-quality and adequately powered studies comparing different strategies of physiologic myocardial suppression are needed. Nevertheless, the challenges relating to incomplete suppression of physiological myocardial glucose utilization in a small proportion of studies are likely to persist; therefore, the development of alternative targeted inflammation imaging radiotracers would be useful.

NEW KNOWLEDGE GAINED

This paper provides a unique review of the available literature regarding preparation for cardiac 18F-FDG PET imaging. The data support the use of high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet for at least two meals with a fast of at least 4 hours for optimal suppression of physiologic myocardial glucose utilization. Because there is no single superior patient preparation technique, each institution should continuously evaluate their image quality data to ensure that greater than 80% of the scans achieve adequate suppression of 18F-FDG.

Abbreviations

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- PET

Positron emission tomography

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12350-016-0502-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Disclosure

Dr Murthy owns stock in General Electric, Cardinal Health and Mallinckrodt. Drs Osborne, Hulten, Skali, Taqueti, Dorbala, DiCarli and Blankstein have no disclosures or conflicts of interest related to this publication. The opinions and assertions contained herein are the authors’ alone and do not represent the views of the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the US Army, or the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Blankstein R, Lundbye J, Heller G. Proceedings of the ASNC cardiac PET summit meeting, May 12 2014, Baltimore MD. J Nucl Cardiol. 2015;22:720–9. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cautela J, Alessandrini S, Cammilleri S, Giorgi R, Richet H, Casalta JP, et al. Diagnostic yield of FDG positron-emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with CEID infection: A pilot study. Europace. 2013;15:252–7. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saby L, Laas O, Habib G, Cammilleri S, Mancini J, Tessonnier L, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography for diagnosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis: Increased valvular 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake as a novel major criterion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2374–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blankstein R, Osborne M, Naya M, Waller A, Kim CK, Murthy VL, et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography enhances prognostic assessments of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;21:166–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morooka M, Moroi M, Ito K, Wu J, Nakagawa T, Kubota K, et al. Long fasting is effective in inhibiting physiological myocardial 18F-FDG uptake and for evaluating active lesion of cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2014;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manabe O, Yoshinaga K, Ohira H, Masuda A, Sato T, Tsujino I, et al. The effects of 18-h fasting with low-carbohydrate diet preparation on suppressed physiological myocardial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake and possible minimal effects of unfractionated heparin use in patients with suspected cardiac involvement sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016;23:244–52. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0226-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demeure F, Hanin FX, Bol A, Vincent MF, Pouleur AC, Gerber B, et al. A randomized trial on the optimization of 18F-FDG myocardial uptake suppression: Implications for vulnerable coronary plaque imaging. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1629–35. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.138594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wykrzykowska J, Lehman S, Williams G, Parker JA, Palmer MR, Varkey S, et al. Imaging of inflamed and vulnerable plaque in coronary arteries with 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with suppression of myocardial uptake using a low-carbohydrate, high-fat preparation. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:563–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Depre C, Vanoverschelde JL, Taegtmeyer H. Glucose for the heart. Circulation. 1999;99:578–88. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mochizuki T, Tsukamoto E, Kuge Y, Kanegae K, Zhao S, Hikosaka K, et al. FDG uptake and glucose transporter subtype expressions in experimental tumor and inflammation models. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1551–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuutila P, Koivisto VA, Knuuti J, Ruotsalainen U, Teras M, Haaparanta M, et al. Glucose-free fatty acid cycle operates in heart and skeletal muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1767–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI115780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada S, Kubota K, Kubota K, Ido T, Tamahashi N. High accumulation of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in turpentine-induced inflammatory tissue. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyagawa M, Yokoyama R, Nishiyama Y, Ogimoto A, Higaki J, Mochizuki T. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography for imaging inflammatory cardiovascular disease. Circ J. 2014;78:1302–10. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-14-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bax JJ, Veening MA, Visser FC, van Lingen A, Heine RJ, Cornel JH, et al. Optimal metabolic conditions during fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose imaging; A comparative study using different protocols. Eur J Nucl Med. 1997;24:35–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01728306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garfein O. Current concepts in cardiovascular physiology. Burlington: Elsevier Science; 2012. p. 565. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang R, Wang JT, Wang L, Le K, Huang Y, Hickey AJ, et al. Impact of patient preparation on the diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG PET in cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nuc Med. 2015 doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harisankar CN, Mittal BR, Agarwal KL, Abrar ML, Bhattacharya A. Utility of high fat and low carbohydrate diet in suppressing myocardial FDG Uptake. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18:926–36. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soussan M, Brilley PY, Nunes H, Pop G, Ouvrier MJ, Naggara N, et al. Clinical value of a high-fat and low-carbohydrate diet before FDG-PET/CT for evaluation of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20:120–7. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng VY, Slomka PJ, Ahlen M, Thomson LE, Waxman AD, Berman DS. Impact of carbohydrate restriction with and without fatty acid loading on myocardial 18F-FDG uptake during PET: A randomized controlled trial. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17:286–91. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9179-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi Y, Kumita S, Fukushima Y, Ishihara K, Suda M, Sakurai M. Significant suppression of myocardial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake using 24-h carbohydrate restriction and a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. J Cardiol. 2013;62:314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balink H, Hut E, Pol T, Flokstra FJ, Roef M. Suppression of 18F-FDG myocardial uptake using a fat-allowed, carbohydrate-restricted diet. J Nucl Med Technol. 2011;39:185–9. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.110.076489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P, Patel CD, Singla S, Malhotra A. Effect of duration of fasting and diet on the myocardial uptake of fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (F-18 FDG) at rest. Indian J Nucl Med. 2014;29:140–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-3919.136559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coulden R, Chung P, Sonnex E, Ibrahim Q, Maguire C, Abele J. Suppression of myocardial 18F-FDG uptake with a preparatory “Atkins-style” low-carbohydrate diet. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:2221–8. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholtens AM, Verberne HJ, Budde RP, Lam MG. Additional heparin pre-administration improves cardiac glucose metabolism over low carbohydrate diet alone in 18F-FDG-PET imaging. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:568–73. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.166884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lum DP, Wandell S, Ko J, Koel MN. Reduction of myocardial 2-deoxy-2[18F]fluoro-D-glucose uptake artifacts in positron emission tomography using dietary carbohydrate restriction. Mol Imaging Biol. 2002;4:232–7. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(01)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee HY, Nam HY, Shin SK. Comparison of myocardial F-18 uptake between overnight and non-overnight fasting in non-diabetic healthy subjects. Jpn J Radiol. 2015;33:385–91. doi: 10.1007/s11604-015-0428-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asmal AC, Leary WP, Thandroyen F, Botha J, Wattrus S. A dose-response study of the anticoagulant and lipolytic activities of heparin in normal subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;7:531–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb01000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaeta C, Fernández Y, Pavía J, et al. Reduced myocardial 18F-FDG uptake after calcium channel blocker administration: Initial observation for a potential new method to improve plaque detection. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:2018–24. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1873-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Japanese Society of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. Diagnostic standard and guideline for sarcoidosis. Tokyo: Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2006. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soejima K, Yada H. The work-up and management of patients with apparent or subclinical cardiac sarcoidosis: With emphasis on the associated heart rhythm abnormalities. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:578–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel MR, Cawley PC, Heitner JF, Klem I, Parker MA, Jaroudi WA, et al. Detection of myocardial damage in patients with sarcoidosis. Circulation. 2009;120:1969–77. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.851352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorbala S, Di Carli MF, Delbeke D, Abbara S, DePuey EG, Dilsizian V, et al. SNMMI/ASNC/SCCT guideline for cardiac SPECT/CT and PET/CT 1. 0. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1485–507. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.105155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vik-Mo H, Mjøs OD. Influence of free fatty acids on myocardial oxygen consumption and ischemic injury. Am J Cardiol. 1981;2:361–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]