Abstract

Introduction and purpose

Sarcopenia is defined as a decrease in muscle mass and muscle strength, and it has been demonstrated to be an adverse predictor in numerous types of cancers. Exercise therapy (ET) carries multiple health benefits in several diseases. Despite these clinical benefits, there are limited data available regarding patients with pancreatic cancer (PC) undergoing ET. We aim to prospectively examine the effect of ET on sarcopenia in patients with PC.

Methods and analysis

All clinical stages of PC can be included. When registering study subjects, a precise evaluation of the nutritional status and the daily physical activities performed will be undertaken individually, for each participant. Study participants will be randomly allocated into two groups: (1) the ET and standard therapy group and (2) the standard therapy group. Amelioration of sarcopenia at 3 months postrandomisation will be the primary endpoint. Muscle mass will be calculated using bioimpedance analysis. Sarcopenia will be defined based on the current Asian guidelines. Participants will be instructed to perform exercises with > 3 metabolic equivalents (mets; energy consumption in physical activities/resting metabolic rate) for 60 min/day and to perform exercises with > 23 mets/week. In the ET group, physical activities equal to or greater than walking for 60 min/day will be strongly recommended.

Ethics and dissemination

The Institutional Review Board at Hyogo College of Medicine has approved this study protocol (approval no. 2772). The final data will be publicly announced. A report releasing the study results will be submitted for publication.

Trial registration number

UMIN000029271; Pre-results.

Keywords: cancer, clinical trials, gastrointestinal neoplasia, nutritional status, pancreatic cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, the current clinical trial is the first prospective interventional study (randomised trial) to examine the effect of exercise therapy on sarcopenia in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Our study results will be limited to a Japanese population, and further validation studies on other ethnic backgrounds will be required.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) has been reported to be the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1–4 Majority of patients with PC present with locally advanced or metastatic disease at initial diagnosis and the proportion of patients with PC who can proceed with curative intent (eg, surgical resection) is <20%.1–4 Currently, there is no standard programme for screening patients at a high risk of PC.1–4 Treatment for unresectable PC has traditionally involved use of gemcitabine with low response rates and a marginal survival benefit.5 6

On the other hand, regular physical activity favourably affects the risk of disease onset and progression of several chronic diseases.7–12 A recent study reported that elimination of physical inactivity would increase the life expectancy of the world’s population by 0.68 years.7 However, the clinical impact of exercise therapy (ET) on patients with PC is poorly understood.

Decrease in muscle mass and muscle strength which is related to ageing is termed as primary sarcopenia, while secondary sarcopenia is defined as a decrease in muscle mass and muscle strength that accompanies underlying diseases such as chronic inflammatory diseases, advanced malignancies and malnutrition.13–17 In the field of malignancies, sarcopenia has been demonstrated to be an adverse predictor in numerous types of cancers.18 19 Pretherapeutic sarcopenia is highly prevalent in patients with malignancies.18 19 In our previous investigation, we demonstrated that decreased skeletal muscle mass could be a significant predictor of prognosis in patients with unresectable advanced PC undergoing systemic chemotherapy, and some interventions for patients with sarcopenic PC could be beneficial for ameliorating clinical outcomes.20

Again, ET brings multiple health benefits both in healthy individuals and several diseases.7–12 21–23 Despite these clinical benefits, there are limited data available regarding patients with PC undergoing ET. There is therefore a need to investigate this issue. In this study, we aim to prospectively examine the effect of ET on sarcopenia in patients with PC.

Patient eligibility criteria

In malnourished patients with PC, ET may be accompanied with increased health risks, as ET may accelerate further protein catabolism and muscle mass decrease.24–26 While registering study subjects, a precise evaluation of the nutritional status and the daily physical activities performed will be undertaken individually for each participant. For all potential participants, the researchers will explain in detail the study aims, procedure and potential benefits and risks of this study in a written informed manner. The researchers must let all potential participants know that he/she has the right to withdraw consent at any time throughout the study period. All potential participants must be given sufficient time for careful consideration prior to making a decision. All participants must sign the consent before he/she can participate in the study. Written informed consents will be kept as a part of the clinical trial documents.

Inclusion criteria

Both sexes.

Patients with PC aged ≥20 years. PC includes all type of pancreatic malignancies. A diagnosis of PC will be based on the current Japanese guidelines.27 Clinical stage for PC will be determined based on Union for International Cancer Control classification system.28

Patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) 0 or 1.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with severe depression or psychiatric disorder.

Patients with far advanced PC with massive ascites or extensive metastases due to which participation in this study is anticipated to be difficult.

Patients with severe underlying diseases, such as severe infectious diseases, severe chronic heart failure and/or respiratory disorders.

Pregnant or lactating female patients.

Patients who may be at a risk of fall.

Patients considered unsuitable for the study because of the inability to participate in ET.

Patients considered unsuitable for the study because of other reasons.

Study protocol

Study design: single-centre non-double blind randomised controlled trial

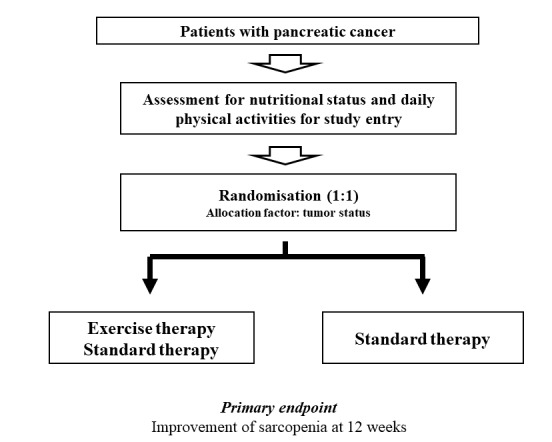

Our study participants will be patients with PC. All clinical stages (stage I, II, III and IV) of PC can be included. Standard therapy for each patient with PC will be permitted. Study participants will be randomly allocated into two groups: (1) the ET and standard therapy group and (2) the standard therapy group (figure 1). Standard therapies such as surgical resection and systemic chemotherapy will be chosen based on tumour status and baseline characteristics in each patient after thorough discussion with surgeons and oncologists.20 27

Figure 1.

Study design.

Exercise therapy

In the ET group, guidance for ET will be provided for each participant once a month at the outpatient nutritional guidance clinic. Participants will also be instructed to perform exercises with > 3 metabolic equivalents (mets; energy consumption in physical activities/resting metabolic rate) for 60 min/day and to perform exercises >23 mets/week.7–12 In the ET group, physical activities equal to or greater than walking for 60 min/day will be strongly recommended for each study participant. In both groups, standard therapies for PC will be allowed and we will ask all study participants to self-declare their daily amount of exercise. Direct monitoring of exercise will not be undertaken.

Time of starting ET

In the ET group, when the general condition of the patient is stable after initial standard therapy, and it is judged by the attending physician that ET can be performed safely, it will be started as soon as possible.

Primary endpoints

Sarcopenia improvement

Muscle mass, using bioimpedance analysis (BIA) and analysis of muscle strength (hand-grip strength) for the evaluation of sarcopenia, will be calculated once each month. Sarcopenia will be defined based on the current Asian guidelines.15 The cut-off values for hand grip strength are <26 kg in male and <18 kg in female patients and those for muscle mass in BIA are <7.0 kg/m2 in male and <5.7 kg/m2 in female patients.15 Patients who meet both these criteria will be defined as patients with sarcopenia. Amelioration of sarcopenia at 3 months postrandomisation will be the primary endpoint.29 We will prospectively compare the amelioration of sarcopenia within the two groups.

Secondary endpoints (examination for study)

Changes over time in baseline characteristics

We will assess changes over time of the following baseline characteristics: body weight, body mass index, white blood cell count, platelet count, serum albumin level, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total cholesterol, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, fasting blood glucose, haemoglobin A1c, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance and tumour markers

Follow-up and standard of care

During the observation period and after completion of the study, all study subjects will be seen in our clinic every 4 weeks to address complications of PC and other comorbidities. In both groups, standard therapies for PC will be continued. Regular laboratory tests (haematology, biochemistry and coagulation) will be requisite at study entry and at completion of the study and on an as-required basis.

Case registration period

From October 2017 to March 2021.

Data collection

A study assistant will gather data elements from the patient medical records, including the following:

Baseline data:

Sex and age

Height and body weight

Vital signs and ECOG-PS

History of alcohol consumption and history of smoking

Clinical stage of PC

Previous treatment and medication

Comorbid conditions

Baseline laboratory tests

Presence or absence of ascites on radiological findings

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics

Data will be entered using JMP software (SAS Institute), and all data will be checked to confirm consistency. Data at each time point will be compared. Quantitative parameters will be compared using a paired or an unpaired t-test. Categorical parameters will be compared using Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test, as applicable. Statistical analyses will be undertaken on an intention-to-treat basis, and all patients will be analysed in the group to which they are assigned.

Sample size estimation

According to our previous BIA results, considering that the α error (type 1 error) is 0.05, the detection power (β) is 0.8, the difference in the two groups to be detected and measured using BIA is 10, and the SD of outcome is 10, the number of required participants in each group will be 17 (total of 34 participants) in order to randomly allocate one to one.30 31 Randomisation will be performed using a dedicated computer and using the clinical stage of PC as an allocation factor for matching baseline characteristics between the two groups. We anticipate that a few of the participants may drop out of the study; therefore, a total of 40 participants will be required to confirm our hypothesis.

Discussion

The population of Japan has the longest life expectancy in the world.11 Japan is an ageing country, and the clinical importance of ET has recently gained considerable attention due to its multiple health benefits.7–12 21–23 Sarcopenia is closely associated with ageing and underlying disease and ET has been shown to impact epigenetic modulation, reducing the risk and mortality in patients with malignancies.30 32 33 In addition, ET may have a potential favourable impact on tumour outcome by reducing insulin resistance and insulin-like growth factor-1 secretion.34 Based on this background, we conducted the current randomised controlled trial (RCT). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective interventional clinical trial that will objectively assess the effect of ET on sarcopenia in patients with PC. From a clinical practice perspective, we highlight the potential safety risks of ET in malnourished patients with PC, because ET may risk promoting further protein catabolism and muscle mass loss. An appropriate nutritional assessment will be needed prior to starting ET and this study will be performed with sufficient care.

One of the major strengths of our study is that this will be an RCT. We acknowledge several limitations of this study design. First, this study will be based solely on a Japanese population. Additional research in different ethnic populations will be required to further verify the efficacy of ET in sarcopenia and to extrapolate our results to other ethnicities. Second, direct monitoring of ET will not be undertaken. Third, short duration of ET alone cannot assess the clinical outcome in patients with PC. However, if the clinical efficacy of ET for sarcopenia in patients with PC is confirmed in this RCT, the information provided may be beneficial to clinicians.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics approval

The study protocol, informed consent form and other submitted documents were reviewed and approved. Throughout the study period, Declaration of Helsinki will be strictly followed in order to guarantee the rights of the study subjects. No patient is registered at the time of submission of our manuscript.

Confidentiality

Personal information of all study subjects will be kept confidential. All relevant documents will be kept locked and preserved at the department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Hyogo College of Medicine, Hyogo, Japan, in accordance with data protection procedures. For each study subject, all data collected during the study period will be identified by a serial number and a name acronym in the case report forms.

Dissemination policy

Final data will be publicly disseminated irrespective of the study results. Results will be presented at relevant conferences and submitted to an appropriate journal following trial closure and analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: KY: designed the study and will write the initial draft of the manuscript. HN and HE: will do analysis and interpretation of the data, and assist in preparation of the manuscript. All other authors: will do data collection and interpretation, and will critically review the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2013. Ann Oncol 2013;24:792–800. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kamisawa T, Wood LD, Itoi T, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2016;388:73–85. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00141-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cid-Arregui A, Juarez V. Perspectives in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:9297–316. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2011;378:607–20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borazanci E, Von Hoff DD. Nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine for the treatment of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;8:739–47. doi:10.1586/17474124.2014.925799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thota R, Pauff JM, Berlin JD. Treatment of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a review. Oncology 2014;28:70–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012;380:219–29. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Samitz G, Egger M, Zwahlen M. Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:1382–400. doi:10.1093/ije/dyr112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zheng H, Orsini N, Amin J, et al. Quantifying the dose-response of walking in reducing coronary heart disease risk: meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:181–92. doi:10.1007/s10654-009-9328-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599979_eng.pdf [PubMed]

- 11. Ikeda N, Inoue M, Iso H, et al. Adult mortality attributable to preventable risk factors for non-communicable diseases and injuries in Japan: a comparative risk assessment. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001160 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sofi F, Valecchi D, Bacci D, et al. Physical activity and risk of cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Intern Med 2011;269:107–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02281.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing 2010;39:412–23. doi:10.1093/ageing/afq034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tieland M, Trouwborst I, Clark BC. Skeletal muscle performance and ageing. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:95–101. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marty E, Liu Y, Samuel A, et al. A review of sarcopenia: enhancing awareness of an increasingly prevalent disease. Bone 2017;105:276–86. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishikawa H, Enomoto H, Ishii A, et al. Elevated serum myostatin level is associated with worse survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017;8:915–25. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pamoukdjian F, Bouillet T, Lévy V, et al. Prevalence and predictive value of pre-therapeutic sarcopenia in cancer patients: a systematic review. Clin Nutr 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.07.010 [Epub ahead of print 13 Jul 2017]. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carneiro IP, Mazurak VC, Prado CM. Clinical Implications of sarcopenic obesity in Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2016;18:62 doi:10.1007/s11912-016-0546-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ishii N, Iwata Y, Nishikawa H, et al. Effect of pretreatment psoas muscle mass on survival for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer undergoing systemic chemotherapy. Oncol Lett 2017;14:6059–65. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.6952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mikkelsen K, Stojanovska L, Polenakovic M, et al. Exercise and mental health. Maturitas 2017;106:48–56. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mohammed J, Derom E, Van Oosterwijck J, et al. Evidence for aerobic exercise training on the autonomic function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2017.07.004 [Epub ahead of print 22 Jul 2017]. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grazioli E, Dimauro I, Mercatelli N, et al. Physical activity in the prevention of human diseases: role of epigenetic modifications. BMC Genomics 2017;18(Suppl 8):802 doi:10.1186/s12864-017-4193-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pausch T, Hartwig W, Hinz U, et al. Cachexia but not obesity worsens the postoperative outcome after pancreatoduodenectomy in pancreatic cancer. Surgery 2012;152(Suppl 1):S81–8. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nemer L, Krishna SG, Shah ZK, et al. Predictors of pancreatic cancer-associated weight loss and nutritional interventions. Pancreas 2017;46:1152–7. doi:10.1097/MPA.0000000000000898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vigano A, Kasvis P, Di Tomasso J, et al. Pearls of optimizing nutrition and physical performance of older adults undergoing cancer therapy. J Geriatr Oncol 2017;8:428–36. doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2017.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamaguchi K, Okusaka T, Shimizu K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for pancreatic cancer 2016 from the Japan pancreas society: a synopsis. Pancreas 2017;46:595–604. doi:10.1097/MPA.0000000000000816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1471–4. doi:10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buffart LM, Kalter J, Sweegers MG, et al. Effects and moderators of exercise on quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 34 RCTs. Cancer Treat Rev 2017;52:91–104. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nishikawa H, Shiraki M, Hiramatsu A, et al. Japan Society of Hepatology guidelines for sarcopenia in liver disease (1st edition): recommendation from the working group for creation of sarcopenia assessment criteria. Hepatol Res 2016;46:951–63. doi:10.1111/hepr.12774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nishikawa H, Enomoto H, Iwata Y, et al. Clinical utility of bioimpedance analysis in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017;24:409–16. doi:10.1002/jhbp.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Slattery ML, Curtin K, Wolff RK, et al. Diet, physical activity, and body size associations with rectal tumor mutations and epigenetic changes. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:1237–45. doi:10.1007/s10552-010-9551-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yuasa Y, Nagasaki H, Akiyama Y, et al. DNA methylation status is inversely correlated with green tea intake and physical activity in gastric cancer patients. Int J Cancer 2009;124:2677–82. doi:10.1002/ijc.24231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, et al. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:815–40. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]