Abstract

Purpose

Peroxisomes perform complex metabolic and catabolic functions essential for normal growth and development. Mutations in 14 genes cause a spectrum of peroxisomal disease in humans. Most recently, PEX11B was associated with an atypical peroxisome biogenesis disorder (PBD) in a single individual. In this study, we identify further PEX11B cases and delineate associated phenotypes.

Methods

Probands from three families underwent next generation sequencing (NGS) for diagnosis of a multisystem developmental disorder. Autozygosity mapping was conducted in one affected sibling pair. ExomeDepth was used to identify copy number variants from NGS data and confirmed by dosage analysis. Biochemical profiling was used to investigate the metabolic signature of the condition.

Results

All patients presented with bilateral cataract at birth but the systemic phenotype was variable, including short stature, skeletal abnormalities, and dysmorphism—features not described in the original case. Next generation sequencing identified biallelic loss-of-function mutations in PEX11B as the underlying cause of disease in each case (PEX11B c.235C>T p.(Arg79Ter) homozygous; PEX11B c.136C>T p.(Arg46Ter) homozygous; PEX11B c.595C>T p.(Arg199Ter) heterozygous, PEX11B ex1-3 del heterozygous). Biochemical studies identified very low plasmalogens in one patient, whilst a mildly deranged very long chain fatty acid profile was found in another.

Conclusions

Our findings expand the phenotypic spectrum of the condition and underscore congenital cataract as the consistent primary presenting feature. We also find that biochemical measurements of peroxisome function may be disturbed in some cases. Furthermore, diagnosis by NGS is proficient and may circumvent the requirement for an invasive skin biopsy for disease identification from fibroblast cells.

Keywords: congenital cataract, PEX11B, peroxisome biogenesis disorder, genomics, next-generation sequencing

Eukaryotic peroxisomes are single-membrane bound organelles harboring enzymes that operate in metabolic pathways critical for normal human development and health and are present in almost all cells.1 Peroxisomes show diversity and plasticity, responding rapidly to meet the metabolic needs of the cell.2 Amongst other roles, they are vital for the catalysis of fatty acid α- and β-oxidation in energy metabolism,3 bile acid production for the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins for skin health,4 the formation of plasmalogen for the myelination nerve cells, and for the protection of cells of the cardiovascular and immune systems against reactive oxygen species.5

Human peroxisomal disease is caused by mutations in the genes encoding two classes of protein: single enzyme or metabolite transporter defects known as peroxisomal enzyme deficiencies (PEDs), the clinical and biochemical effects of which are dependent on the specific function of the affected protein; or peroxisome biogenesis disorders (PBDs) that result from a universal abnormality of peroxisome function due to a specific defect in one of the processes crucial for the assembly or maintenance of peroxisomes (reviewed by Waterham et al.6). Peroxisome biogenesis disorders are a genetically heterogeneous group of disorders caused by biallelic mutations in peroxin (PEX) genes. Peroxins are crucial for multiple aspects of peroxisome biogenesis such as the maturation of pre-peroxisomes via the import of peroxisomal membrane and matrix proteins,7 as well as peroxisome growth, division, fission, and proliferation.2,6,8,9 Fourteen of 16 known human PEX genes have been linked to PBDs in humans and are known to cause a spectrum of developmental brain disorders with a combined estimated incidence of 1/50,000.2 Phenotypic severity ranges from acute, multisystemic disease leading to death in childhood as in the Zellweger syndrome spectrum (ZSS) encompassing Zellweger syndrome, infantile refsum disease, and neonatal adrenoleukodystrophy (reviewed by Wanders1 and Waterham et al.6); to comparatively mild, later-onset, or slowly progressive disorders, recently associated with mutations in specific PEX genes.10–12

PEX11B encodes a peroxisomal membrane protein predicted to harbor two transmembrane domains and has cytosol exposed N- and C-termini.13,14 In 2012, Ebberink et al.10 reported a homozygous nonsense mutation in PEX11B in a single patient with a mild Zellweger spectrum phenotype of bilateral congenital cataract, progressive deafness, polyneuropathy, gastrointestinal problems, and mild intellectual disability (PBD 14B, #MIM 614920).10 Immunofluorescence staining in patient fibroblast cells showed aberrant peroxisome quantity, morphology, and division dynamics.10 Interestingly, all standard biochemical measurements of peroxisomal disease were unhelpful in diagnosing this patient. Here we report three further families with PEX11B mutations and mild biochemical disturbances in association with a range of abnormal features including some additional to those reported by Ebberink et al.,10 offering further delineation of the PEX11B phenotype and biochemical profile.

Methods

Ethics, Patient Recruitment, and Clinical Assessment

This research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and ethics committee approval was obtained from the North West Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0421) and the Scottish Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (04:MRE00/19). Written informed consent was obtained for each affected individual as an essential pre-requisite for study inclusion. Patients were assessed through the clinical genetics service at their respective referral center, where they underwent full ophthalmic, developmental, and dysmorphology examinations. A three-generation family history and full medical history were obtained in each case.

Molecular Investigations

Autozygosity Mapping

DNA from I.1 and I.2 underwent Genome-Wide SNP analysis using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide SNP6.0 microarray. Genotypes were generated using the Birdseed V2 algorithm with a confidence threshold of 0.01, and copy number data were generated using the SNP 6.0 CN/LOH Algorithm both within the Affymetrix Genotyping console. Autozygosity analysis was carried out using AutoSNPa (http://dna.leeds.ac.uk/autosnpa/, in the public domain). Copy number results were analyzed using the Affymetrix Chromosome Analysis Suite. Autozygous regions over 5 Mb that were shared between the affected family members were used to guide analysis of whole exome sequencing (WES) data.

Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Whole Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples according to local protocols. DNA libraries for whole-exome sequencing were prepared using 3 μg of high quality DNA. Enrichment of the libraries was conducted using Nimblegen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library version 3.0 (Roche Nimblegen, Madison, WI, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions, for the capture of the coding and flanking intronic regions of all RefSeq RefGene CDS and miRBase version 14 genes. Library preparations were sequenced on the HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocols. Sequencing reads were aligned to the GRCh37 human reference sequence with the Burrows-Wheeler aligner (BWA version 0.6.2).15 The Genome Analysis Tool Kit Lite (GATK version 2.0.39)16 was used for base quality score recalibration and indel realignment prior to variant calling using the unified genotyper (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk, in the public domain).

DNA from II.1 was prepared and enriched for exonic sequence as described above. Sequencing was carried out at the National High-throughput DNA Sequencing Centre (Copenhagen, Denmark). Sequence reads were aligned to the GRCh37 human genome reference assembly with BWA mem 0.7.10. Duplicate reads were marked with Picard MarkDuplicates 1.126. Reads were realigned around indels and base quality scores recalibrated with GATK 3.3. Single nucleotide variants and small indels were called with GATK 3.3 HaplotypeCaller on each sample and GenotypeGVCFs to produce a raw variant call set. Variants were annotated using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor.

Cataract-Targeted NGS

DNA from III.1 was enriched for the coding regions of 115 known bilateral pediatric cataract causing genes ± 50 bp, using an Agilent SureSelect custom designed target-enrichment (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) as described in Gillespie et al.,17 followed by sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform, according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Copy Number Variant (CNV) Detection

Copy number variants were detected from NGS read data using ExomeDepth version 1.1.6.18 Copy number variants were confirmed by dosage PCR (primer details can be found in Supplementary Data SA). Reactions were analyzed against a GS500 ROX standard (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and run on an ABI 3130XL Genetic Analyzer according to manufacturer’s instructions, using a generic Mulitplex Ligation Probe-Dependent Analysis (MLPA) analysis setting.

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) reactions were carried out according to manufacturer’s instructions (Biorad, Hertfordshire, UK). In each reaction, 50 ng of genomic DNA was combined with a VIC-labeled TaqMan genomic control probe (RNAseP; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), primers specific for control or PEX11B loci (Supplementary Data SA), and an appropriate FAM-labeled Universal Probe Library (UPL) probe (Roche, Basel, Switzerland; Supplementary Data SA). Droplets were generated using a Biorad QX200 or QX200AutoDG droplet generator, PCRs were carried out using a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler, and droplets were analyzed on a QX100 Droplet Reader. The data were analyzed using Quantasoft software (QuantaLife, Pleasanton, CA, USA).

Sanger Sequencing

Primers for PEX11B screening were designed to amplify and sequence all coding exons plus intron–exon boundaries of the gene according to RefSeq transcript NM_003846 (see Supplementary Data SA for primer sequences) using BigDye Terminator version 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Biochemical Analysis

Very long chain fatty acid (VLCFA), phytanic and pristanic acid, and/or plasmalogen enzyme measurements in plasma from peripheral blood samples were used to measure peroxisomal biochemical parameters in each case.

Results

Patient Phenotypes

Family I

The affected sibling pair from family I is briefly described in Gillespie et al.19 Patient I.1 was the first born to first cousin parents originating from Bangladesh (Fig. 1). She had a similarly affected male cousin living in Bangladesh but no further information was available. Born at term following an uneventful pregnancy, she initially presented with bilateral, dense cataracts at 6 weeks of age with associated pendular nystagmus and divergent strabismus. She underwent surgical treatment for the cataracts at 3 months. At that time, no other abnormalities were detected.

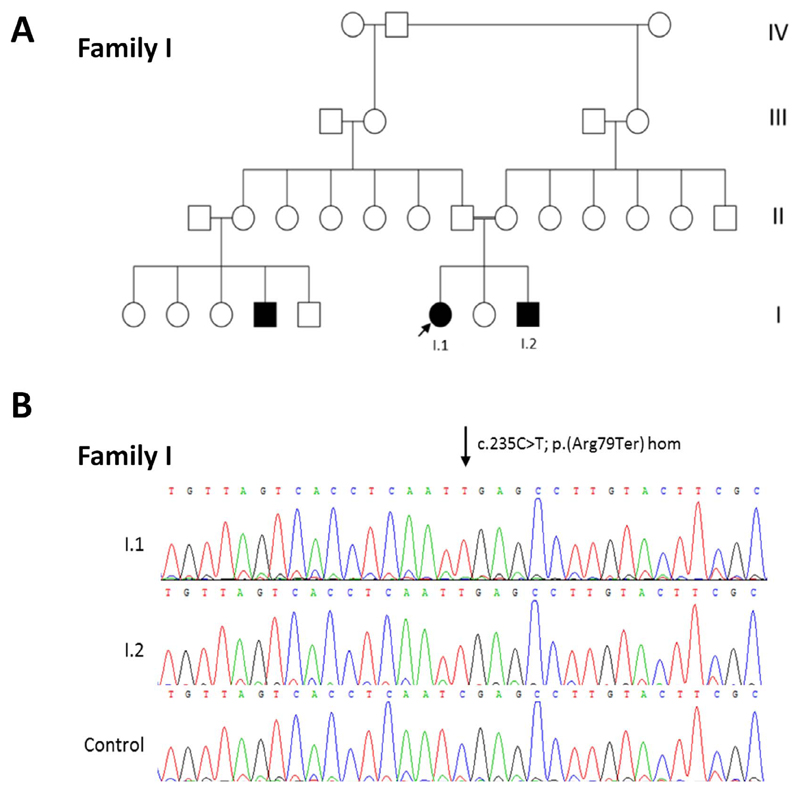

Figure 1.

(A) Pedigree of Family I included in this study. Arrows indicate proband. White square or circle = unaffected individual; black square or circle = affected individual; white circle with black segment = individual reported to have eye problems and short stature but not formal diagnosis; * = individual with eye abnormalities and/or short stature. (B) Family I shows sequencing chromatogram of PEX11B c.235C>T p.(Arg79Ter) homozygous variant in I.1 and I.2 in comparison with control trace (arrow indicates altered nucleotide).

At age 6.5 years, she was noted to have significant short stature (<0.4th centile). Her occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) was on the third centile (Table 1). She also had prominent teeth, a high arched palate, sparse hair with a high frontal hairline, and a lateral flare to her eyebrows. She displayed broad, flat feet with hallux valgus and prominent heels (Fig. 2). A skeletal survey revealed cone-shaped epiphyses of the fingers, a fibrous cortical defect in the upper shaft of the tibia, and a narrow thorax with sloping of the ribs, but no unifying diagnosis could be offered on expert radiologic review. She suffered from severe childhood eczema and mild gastrointestinal problems, experiencing loose stools five to six times per day. She was assessed as having mild learning disability.

Table 1.

Overview of Phenotypic and Genetic Findings in PEX11B Cases

| Family | (Ebberink et al.10) | I | II | III | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient (age [sex]) | 1 (26 y [M]) | I.1 (23 y [F]) | I.2 (6 y 6 mo [M]) | II.1 (6 y 3 mo [F]) | III.1 (2 y 11 mo [M]) | III.2 | ||||||||

| Ethnicity (consanguinity) | Dutch (No) | South Asian (Yes) | South Asian (Yes) | Caucasian (No) | ||||||||||

| Pregnancy (birth weight) | Normal (3.5 kg) | Normal | Normal | IUGR and pre-eclampsia (2.3 kg) | Normal (2.535 kg) | Normal (2.35 kg) | ||||||||

| Bilateral congenital cataract | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Eyes (other) | Nystagmus, photophobia† | Nystagmus, nonreactive pupils, divergent strabismus | Microphthalmia, aphakic glaucoma, B/L phthisis | Aphakic glaucoma | – | – | ||||||||

| Skeletal | ||||||||||||||

| Hands/feet | – | Cone-shaped epiphyses, hallux-valgus | “knobbly” fingers, hallux-valgus | Small hands, short distal phalanges, proximally rotated thumbs, talipes | – | – | ||||||||

| Other | – | FCD of tibia, narrow thorax, sloped ribs, joint laxity | – | Short limbs, scoliosis | – | – | ||||||||

| Skin | Dry; scaly hands and feet | Very dry, severe eczema | Very dry, severe eczema | Dry | – | – | ||||||||

| Hair | – | Sparse | – | Sparse | Medially sparse eyebrows | – | ||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | + | + | + | + | – | – | ||||||||

| Development | ||||||||||||||

| Measurements | ||||||||||||||

| Age | – | 5 y | 12 y | 18.5 y | 7.5 y | 17.5 y | 21 y | 2 y 3 mo | 4.5 y | 6 y 3 mo | 1 y 8 mo | 2 y 11 mo | 1 y 11 mo | 7.5 y |

| Height | n.d. | 90.5 cm | 127.6 cm | 134 cm | 88 cm | 118.8 cm | 127 cm | 78 cm | 90 cm | 105 cm | 81.3 cm | 84 cm | 75.4 cm | 111.4 cm |

| Weight | n.d. | 12 kg | 29 kg | 37.6 kg | 13 kg | 23.3 kg | 26.3 kg | 9.14 kg | n.d. | 20.7 kg | 11.4 kg | 13.2 kg | 10.2 kg | 18.1 kg |

| OFC | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 45 cm | 47 cm | 54 cm | 47.2 cm | 48.5 cm | 45.4 cm | n.d. | ||||

| Milestones | ||||||||||||||

| Sit/crawl | n.d. | n.d. | 1 y | 2 y | n.d. | n.d. | ||||||||

| Walk | 1.5 y* | n.d. | 2 y* | – | 1 y 4 mo | n.d. | ||||||||

| Speech | n.d.* | n.d. | 2 y (babbling)* | 2 y | 1 y 6 mo | n.d. | ||||||||

| Intellectual disability | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Dysmorphism | – | Lateral flare to eyebrows, prominent teeth, high arched palate | Lateral flare to eyebrows | Large fontanelle, short forehead, broad nasal bridge, small mandible | High forehead, broad nasal bridge, epicanthus, upslanting palpebral fissures | – | ||||||||

| Other | – | In-toeing gait attributable to tibial torsion | Abnormal gait | Truncal obesity | – | small, dysplastic nails | ||||||||

| Neurologic | ||||||||||||||

| Tone | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Hypotonia | Hypotonia | n.d. | ||||||||

| Muscular strength | ||||||||||||||

| Upper | Normal | Normal | Reduced | Reduced | n.d. | n.d. | ||||||||

| Lower | Reduced | Normal | Reduced | Reduced | n.d. | n.d. | ||||||||

| Reflexes | ||||||||||||||

| Upper | Reduced | Reduced | n.d. | Increased | n.d. | n.d. | ||||||||

| Lower | Absent | Reduced | n.d. | Increased | n.d. | n.d. | ||||||||

| Hearing | B/L perceptive hearing loss | – | B/L sensorineural hearing loss | – | Conductive hearing loss | – | ||||||||

| Seizures | – | – | – | – | + | – | ||||||||

| Sensory disturbance | + | – | – | – | + | – | ||||||||

| MRI | Chiari malformation type I | Not performed | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | ||||||||

| Other | Behavioral problems, slow to recover from illness, episodes of regression following trauma, reduced muscle bulk | Limb spasticity, feeding difficult to establish, behavioral problems | Behavioral problems, short attention span | |||||||||||

FCD, fibrous cortical defect; n.d.: not disclosed; +, present; –, absent.

Regression after stressful episodes/surgery.

Photophobia occurred as part of migraine-like episodes.

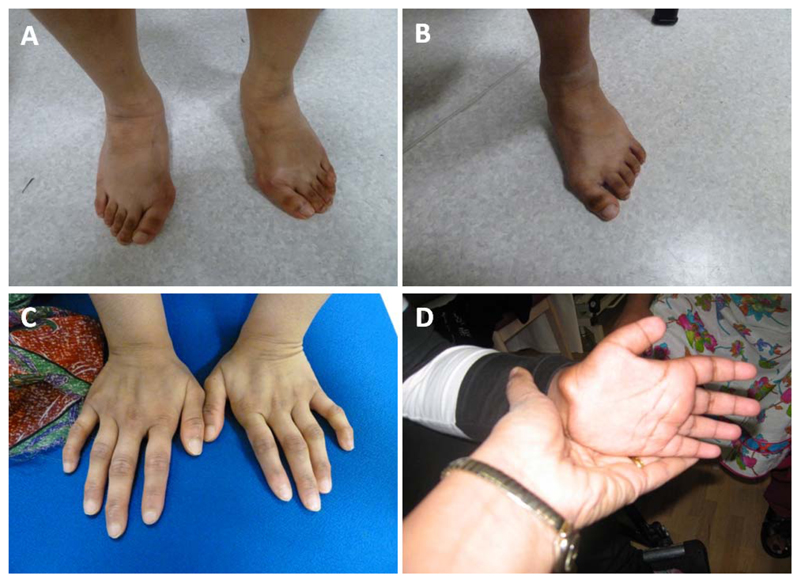

Figure 2.

Abnormalities of the hands and feet of patients with PEX11B mutations. Patient I.1 (A) and patient I.2 (B) showing broad feet and hallux vulgus; hands of patient I.2 (C) showing abnormal metacarpal and phalangeal joints and proximal implanting of the thumb; hands of patient II.1 (D) showing abnormally short distal phalanges and proximal implanting of the thumb.

In patient I.2, bilateral cataracts (removed at 1 month of age) and microphthalmia were observed shortly after birth. He developed glaucoma secondary to surgery. He was generally slow to develop (Table 1). Bilateral sensorineural hearing loss was diagnosed at 4 years. Following this, he went on to develop increasing behavioral and emotional problems, becoming very withdrawn and uncommunicative. He had severe gastrointestinal problems and stopped eating, necessitating a gastrostomy at 6 years of age following which he was slow to recover. Extreme short stature was diagnosed at 14 years for which growth hormone treatment was ineffective. His metacarpal and phalangeal joints were noted to be abnormal, with proximal implanting of the thumb and he had broad, flat feet with hallux valgus and prominent heels (Fig. 2). He is unsteady when walking, demonstrating an unusual in-toeing gait. He was assessed as having moderate intellectual disability.

Family II

Patient II.1, a female, was born at 38 weeks’ gestation weighing 2.3 kg (second centile) to first cousin parents from a large, multiply consanguineous family originating from Pakistan (Fig. 3). Pregnancy was complicated by intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preeclampsia in the third trimester. Family history revealed several affected family members across three generations. Bilateral cataracts were observed at birth and removed at 2 months. Subsequently, she developed aphakic glaucoma. She was also noted to be hypotonic, and this later evolved into four-limb spasticity. Feeding was difficult to establish neonatally. Over the first 6 years of life, her growth parameters remained below the 0.4th centile, and she was slow to reach developmental milestones (Table 1). Her hearing was normal but her speech was slow to develop and by the age of 6 years she was diagnosed with severe intellectual disability. Neurologic assessment detected abnormal muscle tone with reduced muscle strength but increased tendon reflexes. Fine motor skills were present but poor. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan at 6 years was normal. She was noted to be prone to tantrums but had no other behavioral problems. By the age of 13 years, she was still unable to walk; multiple surgeries were attempted to correct progressive talipes but were unsuccessful. Short limbs with small hands and feet were observed. She was described as having stubby fingers and especially short thumbs; her distal phalanges were also abnormally short (Fig. 2). She had very dry skin and sparse hair, which appeared normal upon microscopic analysis. She developed truncal obesity and scoliosis and was noted to be mildly dysmorphic with a large fontanelle, short forehead, broad nasal bridge, and small mandible.

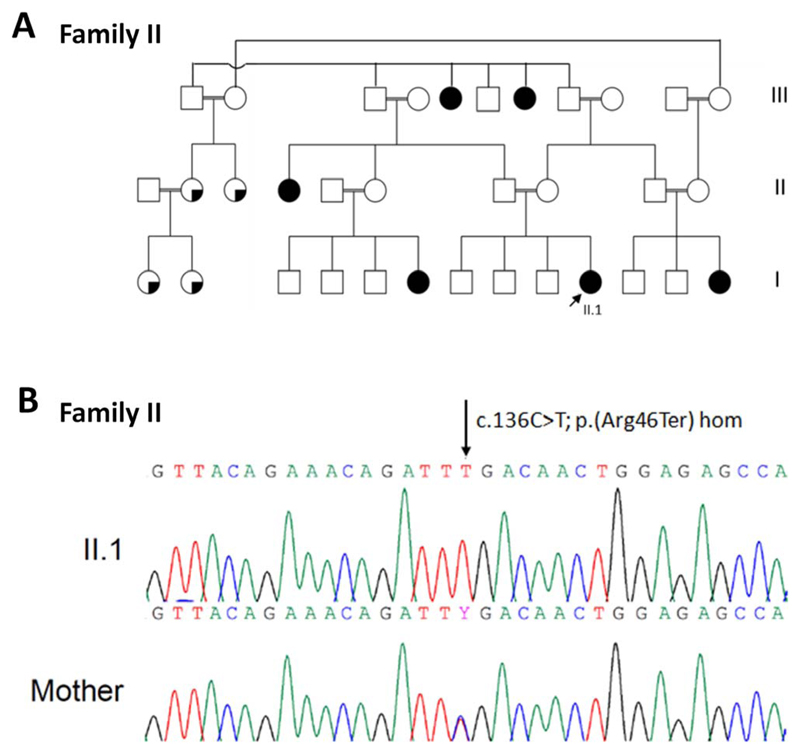

Figure 3.

(A) Pedigree of Family II included in this study. Arrows indicate proband. White square or circle = unaffected individual; black square or circle = affected individual; white circle with black segment = individual reported to have eye problems and short stature but not formal diagnosis; * = individual with eye abnormalities and/or short stature. (B) Family II shows chromatogram of PEX11B c.136C>T p.(Arg46Ter) homozygous variant in II.1 that is heterozygous in his mother (arrow indicates altered nucleotide).

Family III

The proband from family III (III.1; Fig. 4), a Caucasian male, was born at 38 weeks’ gestation weighing 2.353 kg (second centile), following a normal pregnancy. Neonatal examination identified bilateral congenital cataracts that were surgically removed (left eye at 7 weeks of age; right eye at 9 weeks). He walked independently at 16 months, but was delayed with his speech by 18 months, speaking fewer than 30 words. At 20 months, his height and weight were within normal range, though his OFC measured small (47.2 cm, third centile). By the age of 2 years 11 months, all of his growth parameters were below the normal range (Table 1). At 1 year of age, he displayed jerking head movements and an electroencephalogram revealed bisynchronous discharges, suggestive of seizures, but coherence tomography (CT) and MRI scans of his brain were normal. Urea and electrolyte measurements were normal. He was subsequently commenced on sodium valproate. He experienced conductive hearing loss due to mild otitis media with effusion. Behaviorally, he was described as having a sensory disturbance that involved frequent mouthing and licking of objects and a preference for skin-to-skin contact. Development of fine motor skills was delayed. Dysmorphology assessment identified a high forehead, broad nasal bridge, epicanthic folds, upslanting palpebral fissures, and medially sparse eyebrows.

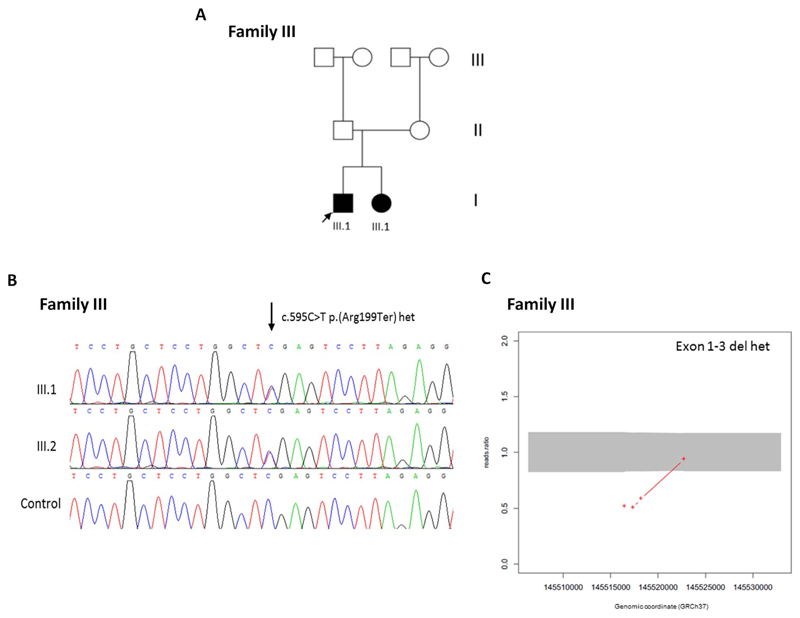

Figure 4.

(A) Pedigree of Family III included in this study. Arrows indicate proband. White square or circle = unaffected individual; black square or circle = affected individual; white circle with black segment = individual reported to have eye problems and short stature but not formal diagnosis; * = individual with eye abnormalities and/or short stature. (B) Family III shows sequencing chromatogram indicating c.595C>T p.(Arg299Ter) heterozygous variant in III.1 and III.2 in comparison with normal control (arrow indicates altered nucleotide). (C) ExomeDepth analysis indicating deletion of exons 1 to 3 of PEX11B according to WES read ratios in patient III.1.

Patient III.2 was born at 38 weeks’ gestation weighing 2.35 kg, following a normal pregnancy (Table1). Bilateral congenital cataracts were noticed at birth and removed at 3 months of age. Clinical examination at 23 months identified developmental delay, but brain MRI was unremarkable. At 7.5 years of age, her weight and weight measurements were on the 0.4th to 2nd centile. She was assessed as having learning difficulties and described as displaying impulsive behavior with no awareness of danger, and poor concentration.

Genomic and Biochemical Analyses

Family I

Autozygosity mapping identified four shared regions of autozygosity on chromosomes 1, 5, 17, and 19 in the affected siblings, I.1 and I.2 (Table 2). Whole exome sequencing data from patient I.1 was enriched for rare (minor allele frequency [MAF] < 0.01), recessive, protein-altering variants within these regions, leading to the identification of a PEX11B c.277C>G p.Arg93X homozygous variant within exon 3, the penultimate coding exon of the gene, at chr1: 145,518,175 (GRCh37; Fig. 1). Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of this variant in her similarly affected sibling, patient I.2. Parental samples were unavailable for testing, but ExomeDepth dosage analysis of sequencing reads mapped to PEX11B did not detect any large deletion or insertion events at this locus (Supplementary Fig. S1). Standard peroxisomal parameters in patient I.2 found blood plasma concentrations of VLCFAs were all within normal range. He had very low plasmalogen levels (C16 dimethyl Acetyl dimethyl acetyl [DMA] = 0.8% [normal range = 3%–15%]); C18 DMA = 1.5% [normal range = 3%–21%]; Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic, Biochemical and Clinical Investigation Results in PEX11B Patients

| Family | PEX11B Mutation(s) | ExAC Frequency | Autozygous Regions | Biochemical Profile | Other Investigations (Result) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | c.235C>T p.(Arg79Ter) hom | – | Chr1: 115,634,100–158,295,100 (42.7 Mb); Chr5: 33,529,100–93,624,300 (60.1 Mb); Chr17: 78,782,220–81,039,680 (2.3 Mb); Chr19: 24,027,080–28,497,590 (4.5 Mb) |

(I.1) FBC: normal; WBC: normal; U&Es: normal; CKs: normal; LFTs: normal; Igs: normal (I.2) VCFLA (μmol/L): C26 = 3.01, C24/C22 = 0.84, C26/C22 = 0.028; phytanic acid: normal; pristanic acid: normal; plasmalogens: C16 DMA 0.8% (very low), C18 DMA 1.5% (very low) |

Skeletal survey: abnormal; ERG: normal; VEP: normal; IOP: normal; fundus exam: normal – |

| II | c.136C>T p.(Arg46Ter) | 8.241e-06 | – | (II.1) VCFLA: C26:0 = 0.548, C24/C22 = 1.213, C26/C22 = 0.03; phytanic acid: normal; pristanic acid: normal | (II.1) MRI: normal; karyotype: normal |

| III | c.595C>T p.(Arg199Ter) het; Exon 1–3 del het | –; – | – | (III.1) VLCFA: normal; LFTs: normal; U&Es: normal | (III.1) ECG: bisynchronous discharges; brain CT: normal; brain MRI: normal; aCGH: normal; skeletal survey: delayed bone age (III.2) Brain MRI: normal |

VCFLA: C26 normal range (μmol/L) = 0.3–4.0; C26:0 normal range = 0.45–1.32; C24/C22 normal range = 0.57–0.92; C26/C22 normal range = 0.003–0.02. Plasmalogens: C16 DMA normal range = 3%–15%; C18 DMA normal range = 3%–21%. aCGH, array comparative genomic hybridization; Chr, chromosome; CKs, creatine kinase levels; del, deletion; ERG, electroretinogram; FBC, full blood count; het, heterozygous; hom, homozygous; Igs, immunoglobulins; IOP, intraocular pressure; LFTs, liver function tests; N.A., not available; U&Es, urea and electrolytes; VEP, visual evoked potentials; WBC, white blood cell count.

Family II

Patient II.1 was initially recruited to a Warburg micro/Martsolf syndrome cohort (PMID: 23420520). Screening of the entire coding region and intron/exon boundaries of RAB3GAP1, RAB3GAP2, RAB18, and TBC1D20 did not identify any putative pathogenic variants. Whole exome sequencing analysis led to the identification of a homozygous PEX11B c.136C>T p.(Arg46Ter) variant within exon 2, at chr1: 145,517,352 (GRCh37; Table 2; Fig. 3). Screening of a further 83 families within the Warburg micro/Martsolf syndrome cohort by Sanger sequencing (data not shown) and ddPCR copy number analysis of a further 28 probands for whom sufficient genomic DNA was available (Supplementary Fig. S2) did not identify any additional pathogenic PEX11B variants.

Patient II.1 was found to have normal phytanic and pristanic acid levels. However, her VLCFA profile was mildly deranged (C26:0 = 0.548 [normal, range = 0.45–1.32], C24:0/C22:0 ratio = 1.213 [elevated, normal range = 0.57–0.92], C26/C22:3 ratio = 0.03 [elevated, normal range = 0.003–0.02]). Interestingly, the C24:0/C22:0 ratio score falls in to the range expected for a Zellweger spectrum disorder (C24:0/C22:0 = 0.92–2.52) unlike previously described for PEX11B-related disease.

Family III

Patient III.1 was referred for cataract-targeted NGS testing, which identified a c.595C>T p.(Arg199Ter) heterozygous variant in exon 4 of PEX11B at chr1: 145,522,734 (GRCh37). Subsequent CNV analysis via Exome-Depth version 1.1.6 indicated a ≥1.87 Kbp heterozygous deletion of PEX11B at chr1: 145516401-145518272 (GRCh37), encompassing exons 1 to 3 (Fig. 4). Dosage analysis was able to confirm the presence of a deletion spanning at least exon 1 to exon 3 PEX11B (Supplementary Fig. S3). Sanger sequencing and dosage analysis was able to confirm the presence of both variants in his similarly affected sibling, patient III.2. Very long chain fatty acid analysis in both III.1 and III.2 was normal (Table 2).

Discussion

In 2012, Ebberink et al.10 described a single patient with a complex multisystem phenotype including bilateral congenital cataract, intellectual disability, bilateral hearing loss, gastrointestinal problems, and episodes of regression following trauma. In this initial report, despite extensive metabolic investigations for a clinically suspected mitochondrial or peroxisome defect, a definitive diagnosis was not reached.10 A defect of peroxisome morphology, proliferation, and division was identified following direct microscopic analysis of cultured patient fibroblasts. Subsequent sequencing of all genes known to be implicated in peroxisome elongation and division led to the identification of a PEX11B c.64C>T p.(Gln22Ter) homozygous variant, assigning this novel and atypical peroxisomal disorder to the milder end of the disease spectrum. The work highlighted the observation that peroxisome biogenesis defects can exist despite normal biochemical measurements of peroxisome function; though electron microscopy of fibroblast samples taken at a skin biopsy may show some characteristic changes.10 However, one would normally have to be prompted to undertake a skin biopsy for diagnosis of a peroxisomal disorder because of abnormal biochemical results, which are not usually present with PEX11B mutations, suggesting direct analytical methods such as genomic analysis can be the most appropriate means of diagnosis for this heterogeneous group of disorders.

Our study provides detailed phenotypic profiles of five additional patients from three families found to harbor biallelic PEX11B mutations via NGS, extending the spectrum and severity of the phenotypes associated with mutations in this gene. In line with the phenotype described for the patient reported by Ebberink et al.,10 all patients described in this study cohort exhibited cataract at birth, underscoring this abnormality as a consistent early feature of the condition. Furthermore, this finding emphasizes the importance of obtaining a precise diagnosis in cases of bilateral pediatric cataract as we have previously demonstrated.17,19 Although congenital cataract is a consistent and obvious early feature of this condition, affected individuals appear otherwise well in infancy. Identification of the precise genetic cause of congenital cataract in infancy enables delineation of disease subtype (i.e., distinguishes isolated cataract from cataract presenting as a syndromic or metabolic condition), allowing the timely implementation of a personalized approach to patient care and importantly, disease-specific monitoring. Two of the five patients described in this cases series developed postoperative (aphakic) glaucoma with patient I.2 going on to develop bilateral phthisis bulbi at 18 years of age, possibly suggesting that patients with PEX11B mutations are at risk of developing problems following eye surgery. Early identification of syndromic forms of pediatric cataract may be used to inform risk of surgical outcomes. Furthermore, monitoring for postoperative complications and observation of the surgical outcomes in further cases of congenital cataract due to PEX11B mutations are indicated to provide more data of the natural history of the eye involvement, which could inform prognosis.

Later in childhood, and further analogous to the original PEX11B patient, all patients in this cohort were found to be developmentally delayed and had intellectual disability. Three of five experienced gastrointestinal abnormalities, two developed hearing loss, and three of five had dry, scaly skin that particularly affected the hands and feet. We also report a number of novel phenotypic features in association with PEX11B peroxisomal disease—all patients in our cohort were found to have short stature and three of five had sparse hair. Two patients had subtle abnormalities of both the axial and appendicular skeleton (patient I.1 and II.1); two were hypotonic, whilst three of five patients were found to have digital abnormalities with hallux-vulgus, prominent joints, or talipes. Interestingly, two patients from different families were found to have dysmorphic facial features reminiscent of more severe Zellweger spectrum of disorders (ZSDs), including large anterior fontanelle, prominent forehead, epicanthic folds, broad nasal bridge, and high arched palate. The same two patients were also found to be hypotonic, and one had experienced a seizure, demonstrating further similarity with more severe ZSDs phenotypes. An interesting observation in II.1, given Ebberink’s description, was the occurrence of episodic bouts of withdrawal and mutism, raising the possibility of a specific behavioral phenotype.

The original PEX11B c.64C>T p.(Gln22Ter) homozygous mutation was confirmed as a protein null mutation via immunoblot analysis in fibroblast protein homogenates.20 The three PEX11B mutations identified by this study are also predicted null genotypes via nonsense mediated decay. However, should the transcript survive, each of these mutations would result in truncation of the protein prior to a C-terminal domain from amino acid 211 to 259 that is thought to be required for homodimerization with PEX11A,21 and interaction with PEX19 and FIS1 for normal peroxisome membrane proliferation and trafficking.14,22 Nonetheless, in each case, the residual peroxisomes are partially functional given the near normal VLCFA results in the probands,20 suggesting redundancy of the gene product. PEX11 (PEX11A, PEX11B, and PEX11G) proteins are known to have an important role in the elongation and constriction of peroxisomes, and PEX11B is known to function in the growth and division pathway of peroxisome biogenesis and specifically in the elongation and constriction of peroxisomes, prior to fission of organelles, orchestrated by DLP1 and FIS1.23,24 Ebberink et al.10 found that when PEX11B deficient fibroblasts were cultured at a high temperature, they lost their ability to import catalase and were slow to recover from this stress, potentially mimicking the slow recovery phenotypes of patients with PEX11B–related disease.6,10

In summary, this study describes a further five individuals from three families with PBD 14B attributable to novel biallelic loss of function mutations in PEX11B. We describe additional phenotypic features to those reported in the first and only description of this disorder,10 thereby expanding the phenotypic spectrum of the disease. Importantly, our findings underscore congenital cataract, the primary presenting feature of the condition, and highlight the importance of determining the precise molecular cause of bilateral cataract in neonates. It is also worth noting the tentative clinical diagnosis of Warburg micro/Martsolf syndrome that was made in one of our cases, suggesting that PEX11B should be considered in such cases that are mutation negative for RAB3GAP1/2, RAB18, and TBC1D20. Our work adds to cumulative evidence that NGS technologies offer a proficient means of diagnosis of this group of genetically heterogeneous and phenotypically variable group of disorders,25–27 especially since PEX11B-related disease escapes detection using standard peroxisomal biochemical measurements. In addition, direct gene analysis through this route avoids the need for diagnosis by invasive skin biopsy, which is not acceptable to all patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the family members for their enthusiastic participation in this study. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of the Manchester Academic Health Science Centre and the Manchester National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre.

Supported by Fight for Sight (grant number: 1831) and the Newlife Foundation for Disabled Children (13–14/02). The funding organization had no role on the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Disclosure: R.L. Taylor, None; M.T. Handley, None; S. Waller, None; C. Campbell, None; J. Urquhart, None; A.M. Meynert, None; J. Ellingford, None; D. Donnelly, None; G. Wilcox, None; I.C. Lloyd, None; H. Mundy, None; D.R. FitzPatrick, None; C. Deshpande, None; J. Clayton-Smith, None; G.C. Black, None

References

- 1.Wanders RJ. Metabolic functions of peroxisomes in health and disease. Biochimie. 2014;98:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith JJ, Aitchison JD. Peroxisomes take shape. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:803–817. doi: 10.1038/nrm3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper TG, Beevers H. Mitochondria and glyoxysomes from castor bean endosperm. Enzyme constitutents and catalytic capacity. J Biol Chemistry. 1969;244:3507–3513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagey LR, Krisans SK. Degradation of cholesterol to propionic acid by rat liver peroxisomes. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1982;107:834–841. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)90598-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagan N, Zoeller RA. Plasmalogens: biosynthesis and functions. Prog Lipid Res. 2001;40:199–229. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waterham HR, Ferdinandusse S, Wanders RJ. Human disorders of peroxisome metabolism and biogenesis. Biochim Biophysica Acta. 2016;1863:922–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theodoulou FL, Bernhardt K, Linka N, Baker A. Peroxisome membrane proteins: multiple trafficking routes and multiple functions? Biochem J. 2013;451:345–352. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motley AM, Hettema EH. Yeast peroxisomes multiply by growth and division. J Cell Biology. 2007;178:399–410. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoepfner D, Schildknegt D, Braakman I, Philippsen P, Tabak HF. Contribution of the endoplasmic reticulum to peroxisome formation. Cell. 2005;122:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebberink MS, Koster J, Visser G, et al. A novel defect of peroxisome division due to a homozygous non-sense mutation in the PEX11 beta gene. J Med Genetics. 2012;49:307–313. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui S, Funahashi M, Honda A, Shimozawa N. Newly identified milder phenotype of peroxisome biogenesis disorder caused by mutated PEX3 gene. Brain Dev. 2013;35:842–848. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mignarri A, Vinciguerra C, Giorgio A, et al. Zellweger spectrum disorder with mild phenotype caused by PEX2 gene mutations. JIMD Rep. 2012;6:43–46. doi: 10.1007/8904_2011_102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schrader M, Reuber BE, Morrell JC, et al. Expression of PEX11beta mediates peroxisome proliferation in the absence of extracellular stimuli. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29607–29614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch J, Pranjic K, Huber A, et al. PEX11 family members are membrane elongation factors that coordinate peroxisome proliferation and maintenance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3389–3400. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillespie RL, O’Sullivan J, Ashworth J, et al. Personalized diagnosis and management of congenital cataract by next-generation sequencing. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2124–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plagnol V, Curtis J, Epstein M, et al. A robust model for read count data in exome sequencing experiments and implications for copy number variant calling. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2747–2754. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillespie RL, Urquhart J, Anderson B, et al. Next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of metabolic disease marked by pediatric cataract. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebberink MS, Koster J, Visser G, et al. A novel defect of peroxisome division due to a homozygous non-sense mutation in the PEX11beta gene. J Med Genetics. 2012;49:307–313. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Gould SJ. The dynamin-like GTPase DLP1 is essential for peroxisome division and is recruited to peroxisomes in part by PEX11. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17012–17020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi S, Tanaka A, Fujiki Y. Fis1, DLP1, and Pex11p coordinately regulate peroxisome morphogenesis. Exper Cell Res. 2007;313:1675–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrader M, Almeida M, Grille S. Postfixation detergent treatment liberates the membrane modelling protein Pex11-beta from peroxisomal membranes. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;138:541–547. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-1010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schrader M, Costello JL, Godinho LF, Azadi AS, Islinger M. Proliferation and fission of peroxisomes: an update. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 2016;1863:971–983. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bacino C, Chao YH, Seto E, et al. A homozygous mutation in PEX16 identified by whole-exome sequencing ending a diagnostic odyssey. Mol Genetics Metabolism Rep. 2015;5:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tran C, Hewson S, Steinberg SJ, Mercimek-Mahmutoglu S. Late-onset Zellweger spectrum disorder caused by PEX6 mutations mimicking X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;51:262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohba C, Osaka H, Iai M, et al. Diagnostic utility of whole exome sequencing in patients showing cerebellar and/or vermis atrophy in childhood. Neurogenetics. 2013;14:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10048-013-0375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.