Abstract

Background

Although individuals with psychiatric disorders are disproportionately affected by cigarette smoking, few outpatient mental health treatment facilities offer smoking cessation services. In this paper, we describe the development of a smartphone-assisted mindfulness smoking cessation intervention with contingency management (SMI-CM), as well as the design and methods of an ongoing pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) targeting smokers receiving outpatient psychiatric treatment. We also report the results of an open-label pilot feasibility study.

Methods

In phase 1, we developed and pilot-tested SMI-CM, which includes a smartphone intervention app that prompts participants to practice mindfulness, complete ecological momentary assessment (EMA) reports 5 times per day, and submit carbon monoxide (CO) videos twice per day. Participants earned incentives if submitted videos showed CO ≤ 6 ppm. In phase 2, smokers receiving outpatient treatment for mood disorders are randomized to receive SMI-CM or enhanced standard treatment plus non-contingent CM (EST).

Results

The results from the pilot feasibility study (N=8) showed that participants practiced mindfulness an average of 3.4 times/day (≥ 3 minutes), completed 72.3% of prompted EMA reports, and submitted 68.0% of requested CO videos. Participants reported that the program was helpful overall (M=4.85/5) and that daily mindfulness practice was helpful for both managing mood and quitting smoking (Ms=4.50/5).

Conclusions

The results from the feasibility study indicated high levels of acceptability and satisfaction with SMI-CM. The ongoing RCT will allow evaluation of the efficacy and mechanisms of action underlying SMI-CM for improving cessation rates among smokers with mood disorders.

1. Introduction

Although smoking prevalence in the U.S. has decreased to 15% (1), smoking rates among individuals with psychiatric disorders remain disproportionately higher than those in the general population (2–4). However, fewer than 20% of outpatient psychiatric treatment facilities offer smoking cessation services (5), wasting a key opportunity to intervene and reduce smoking-related health disparities among psychiatric patients. Development and evaluation of smoking cessation interventions that could be integrated into psychiatric treatment settings is needed.

There is growing interest in mindfulness training for smoking cessation intervention (6–8). Although evidence for the efficacy of mindfulness approaches to smoking cessation is mixed (7–11), preliminary evidence suggests that mindfulness training, even brief exposure delivered via telephone or the internet, may be particularly beneficial for those in greater affective distress (12, 13). Moreover, there is mounting evidence that regular home mindfulness practice plays an important role in improving various outcomes (e.g., smoking behavior, chronic pain, psychological distress, perceived stress) (8, 14–17). Mindfulness training is hypothesized to disrupt core associations between aversive internal states (i.e., craving and negative affect) and behavioral responses (i.e., smoking) (18). In addition, the literature on learning (19, 20) suggests that smokers should be exposed to the internal discomfort inherent to quitting smoking when practicing mindfulness to learn to not respond to smoking cues. That is, practicing mindfulness while abstinent may be crucial for smokers to learn alternative (non-smoking) responses to smoking cues.

In this study, we used contingency management (CM), in which objectively-verified smoking abstinence is rewarded with monetary incentives, to encourage abstinence. Given that CM has been shown to induce short-term smoking abstinence and reduction in patients with serious mental disorders (21–24), it may be an ideal adjunct intervention to ensure opportunities to practice mindfulness while abstinent. Recent advances in smartphone technology have made remote (i.e., home-based) CM procedures possible, reducing participant burden. In fact, smartphones allow for frequent and multiple methods of delivering interventions (e.g., video-capture, prompting practice) in one’s natural environment, such that the intervention (e.g., mindfulness practice and CM procedure) can be fully integrated into daily life and the generalizability of learning that occurs through the intervention is increased. Hence, mindfulness-based interventions using smartphones to enhance efficacy may be particularly promising.

This paper describes the intervention development and study design and methods for an ongoing preliminary randomized controlled trial (RCT), Project mSMART MIND. The primary aim is to develop and test the efficacy of a smartphone-assisted mindfulness-based smoking cessation intervention with contingency management (SMI-CM), designed to help smokers with mood disorders quit smoking. We also report the results of an open-label pilot feasibility study and discuss pertinent considerations.

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Study Design

Project mSMART MIND has 2 phases: 1) intervention development and an open-label pilot feasibility study of the SMI-CM intervention, followed by 2) a pilot RCT. The open-label pilot feasibility study assessed intervention adherence and participant satisfaction to establish the feasibility and acceptability of SMI-CM.

2.2. Phase 1: Intervention Development and Open-label Feasibility Study

2.2.1. SMI-CM Intervention development

The SMI-CM intervention was developed by HM with input from RAB and DW (Principal and Co-Principal Investigators of this project). It consists of individual counseling sessions (delivered in-person and via phone) and a smartphone intervention that comprises 1) daily mindfulness practice, 2) smoking status verification (submitting videos documenting expired carbon monoxide [CO] levels) for CM, and 3) daily reports (ecological momentary assessment, EMA). All participants are provided with a study smartphone (Samsung Galaxy Grand Prime/J3), a hand-held CO monitor (piCO+ Smokerlyzer, Bedfont Inc., Medford, NJ), and up to an 8-week supply of nicotine patches.

2.2.1.1. Individual counseling sessions

Individual sessions were adapted from a previous Mindfulness-Based Addiction Treatment (25), the Tobacco Dependence Treatment Handbook (26), and the U.S. Public Health Service clinical practice guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence (Fiore et al., 2008). Participants receive two individual, in-person counseling sessions (50 – 60 mins each) at 10 days and 3 days prior to a target quit date and two brief phone counseling sessions (15–20 minutes each) at 3 and 10 days after the target quit date. The in-person sessions include psychoeducation, smoking cessation counseling, and an introduction to the theory and practice of mindfulness, including instructions and feedback. At the end of session 1, participants are oriented to the use of the smartphone intervention, and complete one practice daily report to troubleshoot any issues. Participants are then trained to use a CO monitor to submit CO test videos. Training on CO videos is repeated at the end of the second session to ensure mastery. A summary note of the session, handouts discussed during the session, and illustrated instructions on using the smartphone (e.g., volume setting) and the study app (e.g., mindfulness practice, EMA report, submitting CO videos) are provided to participants at the end of each in-person session. The contents of in-person and phone counseling sessions are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Contents of individual counseling sessions.

| In-Person Individual Session #1 (approx. 60 mins) |

|

|

| • Introduce the mSMART MIND smoking cessation program. |

| • Discuss participant’s values, reasons for quitting, negative aspects of smoking, benefits of quitting. |

| • Provide psychoeducation on depression and smoking cessation, nicotine dependence, and health benefits of quitting. |

| • Introduce the concept of mindfulness and its relation to quitting smoking.* |

| • Practice mindfulness exercises: Raisin Exercise and Mindfulness of Breath (using the recording).* |

| • Explore ways to incorporate mindfulness into daily activities.* |

| • Discuss strategies to begin preparing for target quit date: changing routines, monitor smoking patterns, and the importance of social support, practicing mindfulness. ° |

| ✓ Training in smartphone and CO monitor use: Practice completing an EMA report, and taking/submitting a CO video using the smartphone app (additional approx. 15 min~). |

|

|

| In-Person Individual Session #2 (approx. 50 mins) |

|

|

| • Review mindfulness practice and EMA reports completed in the past week. Explore ways to increase completion rates. Troubleshoot, ensure understanding of the app. ° |

| • Discuss participant's experience practicing mindfulness in daily activities and provide feedback. * |

| • Discuss participant’s triggers to smoke in the past week and how being mindful may help reduce automatic response (i.e., smoking) to these triggers. ° |

| • Explore strategies to manage high-risk situations, to receive helpful social support, to reward oneself for not smoking, and for healthy stress management. ° |

| • Discuss their experience with craving, introduce the concept of urge surfing, and explore other ways of coping with strong craving, and briefly review nicotine patch use. ° |

| • Discuss participant’s experience of pleasant moments (e.g., sense of joy, pride, accomplishment) and how they may relate to their core values, and explore ways to increase these moments in daily life. * |

| ✓ Review CO video procedure using the smartphone app (additional approx. 5 min). |

|

|

| Two Brief Phone Sessions (15–20 mins each) |

|

|

| • Discuss the participant’s successes and challenges since target quit date. |

| • Provide encouragement and help identify strategies to stay quit or initiate another quit attempt. |

| • Encourage to continue practicing mindfulness |

indicates sections that included only in the SMI-CM.

indicates sections that included both in the SMI-CM and EST except that references to or information relevant to mindfulness were excluded in the EST.

2.2.1.2. Transdermal nicotine patches

All participants are eligible to receive up to an 8-week supply (4 boxes) of transdermal nicotine patches. The first box (2-week supply) is provided at the first counseling session. Additional boxes are provided upon the participant’s request at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 6 weeks after the target quit date.

2.2.1.3. Smartphone application

The smartphone app was developed in collaboration with TelASK Technology Inc., a company with extensive experience in mobile behavioral interventions and assessments, including smoking cessation. The application randomly prompts participants 5 times per day (at least 1.5 hours apart) during the participant's reported waking hours to complete EMA reports, as well as to engage in mindfulness practice and to complete a post-mindfulness practice report. The app also prompts participants to videotape themselves testing their CO levels twice a day (at the end of the first and last reports of the day) for 14 days following the target quit date.

2.2.1.4. Mindfulness practice

Starting the day after the first counseling session, participants are prompted to practice mindfulness by listening to an audio recording on the smartphone 5 times per day (after completing each EMA report) for a total of 38 days (10 days prior to and 28 days after the target quit date). A total of 3 instructional messages (i.e., introduction, mindfulness and cessation, common challenges during mindfulness practice) and 11 guided mindfulness practice recordings were developed by MF with input from HM, and recorded by MF, a mindfulness expert who has been involved in previous research studies of mindfulness interventions for smoking cessation. During each of 2 phases (the first 14 days and next 24 days), 7 of the recordings become available to participants in a pre-selected order. Once participants complete all recordings available for each phase, they can listen to any of the mindfulness recordings and can also engage in additional practice as often as desired without prompts.

These mindfulness exercises aim to engage participants to practice noticing and observing their own thoughts, feelings, and sensations without judgment in order to increase tolerance and acceptance of negative experiences associated with smoking cessation and encourage flexibility in responding to internal events (e.g., craving, negative affect) without smoking. Each recording lasts approximately 5–7 minutes. Brief descriptions of each recording are listed in Table 2. At the end of the intervention period (4-week post-target quit date), a CD containing all of the mindfulness recordings is provided upon participant request. If desired, mindfulness recordings can be downloaded onto the participant’s personal smartphone.

Table 2.

Brief descriptions of mindfulness recordings.

| Recording | Length (minutes) |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 – The first 2 weeks | ||

| 1. Introduction | 3:57 | Introduction to the concept of mindfulness and how it can be practiced both formally and informally |

| 2. Mindfulness and Smoking Cessation | 4:25 | How mindfulness can aid in quitting smoking by reducing reactivity and impulsiveness to smoking triggers |

| 3. Mindfulness of Breath | 5:02 | Mindfulness meditation to cultivate present-moment awareness, non-reactivity and concentration through mindful breathing |

| 4. Mindfulness of Breath and Body | 5:50 | Mindfulness meditation to increase awareness of physical sensations, thereby cultivating present-moment attention, concentration and understanding of oneself. |

| 5. Mindfulness and Challenges | 7:02 | Challenges experienced in mindfulness practice and daily life, and how mindfulness can be used to handle these challenges |

| 6. Mindfulness of Sound | 4:59 | Mindfulness meditation to cultivate present-moment attention to sound and how sounds affect one’s experience |

| 7. Walking Meditation | 5:31 | Mindfulness meditation to cultivate deeper awareness of walking, leading to greater presence and concentration. |

| 8. Loving-Kindness Meditation | 5:54 | Mindfulness meditation to cultivate kindness and acceptance towards oneself and others |

| Phase 2 – after the 3rd week | ||

| 9. Informal Practice | 6:25 | How mindfulness can be practiced informally in everyday tasks and activities |

| 10. Body Scan | 6:48 | Mindfulness meditation to cultivate body awareness, concentration, self-awareness and the ability to widen or narrow one’s attention |

| 11. Mountain Meditation | 5:56 | Visual meditation to cultivate and connect to inner strength and stability in the face of internal and external challenges |

| 12. Urge Surfing | 5:04 | Mindfulness meditation to help one cope with cravings and to experience urges with curiosity and tolerance |

| 13. Three Minute Space | 4:11 | Guidance in stopping to recognize and create space around patterns of automatic thinking, bodily sensations and emotions. |

| 14. Mindfulness of Thoughts and Feelings | 6:42 | Mindfulness meditation to cultivate non-judgmental awareness to thoughts and feelings |

2.2.1.5. Contingency management (CM)

A CM strategy with a progressive payment schedule is used to increase the likelihood and duration of continued abstinence for the 2 weeks following the participant’s target quit date. Using the video-capture capability of the smartphone’s app, CO levels are tested twice daily (27) (e.g., at the end of the first and last EMA prompt). All participants receive training in taking a video that captures 4 components: 1) the CO monitor showing that it is calibrated to zero, 2) the participant holding his/her breath while the monitor counts down, 3) the participant blowing into the CO monitor and 4) the final CO reading. Video clips are transmitted automatically to the investigators for analysis. Video clips are saved on a secure password-protected server managed by TelAsk. Inc.

Participants receive monetary incentives on an escalating pay schedule contingent on each confirmed CO level of 10 ppm or less on the target quit date and 6 ppm or less thereafter. A 6 ppm limit was chosen due to the urban study location, in which CO can often be detected in non-smokers (28, 29). The first CO sample of 6 ppm or less (or 10 ppm or less on the target quit date) earns a $3.00 voucher (30). Vouchers increase by $0.25 for each consecutive CO sample of 6 ppm or less. Participants also earn a $5.00 bonus for every 3 consecutive CO samples of 6 ppm or less. In all, participants can earn a maximum of $223. If a CO level is greater than 6 ppm, the participant does not receive reinforcement for that sample and the value of the next voucher is reset to $3.00. Payment is provided in cash at the 2-week follow-up visit. Participants can track incentives accumulated to date in the smartphone app (with a line graph showing dollar amount earned over time).

2.2.2. The Open-label Pilot Feasibility Study

We conducted an open-label pilot feasibility study (N = 8) to assess intervention adherence and participant satisfaction in order to establish the feasibility and acceptability of SMI-CM. Study procedures were equivalent to those of the RCT described below except that participants were not randomized (all participants received SMI-CM). The results of the pilot study are presented in the Results section after the description of the RCT protocol.

2.3. Phase II: The RCT: Descriptions of the study protocol

2.3.1. Study Design

The primary aim of the RCT is to test the efficacy of SMI-CM against a comparison intervention, enhanced standard treatment plus non-contingent CM (EST). Abstinence is assessed at 2-week, 4-week, and 3-month post-quit date follow-up visits. We intend to enroll a total of 60 participants with 30 randomized to SMI-CM and 30 to EST.

2.3.2 Study Methods

2.3.2.1. Participants and setting

Participants are recruited from an outpatient psychiatric clinic in the Bronx, NY via an in-person approach by research assistants in the waiting rooms, paper flyers displayed in the outpatient clinic, and medical staff referral. Eligible patients meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) 18 years of age or older, 2) smoking at least 5 cigarettes daily for the past 6 months, 3) English-speaking, 4) intent to quit smoking in the next 3 months, 5) attended a minimum of 3 treatment visits in the past 3 months at the clinic, 6) have a depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, and 7) currently receiving treatment for depression or bipolar disorder. The exclusion criteria are: 1) acute psychiatric symptomatology including current active suicidal ideation, 2) current diagnosis of dementia, cognitive impairment, intellectual disability and/or autistic disorder sufficient to impair provision of informed consent or study participation, 3) diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, 4) current (non-nicotine) substance use disorder with the exception of individuals with at least 6 months of abstinence or currently receiving treatment including counseling and medications (e.g., methadone, suboxone), 5) regular use (4 or more days per week) of other tobacco products or marijuana, 6) use of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation (excluding nicotine replacement therapy) in the past month or current use of nicotine replacement therapy, 7) intention to quit smoking using pharmacotherapy other than transdermal nicotine patches, 8) pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning to become pregnant within 6 months, 9) significant history of cardiovascular disease, or 10) lack of a stable home address where they could reliably be reached.

2.3.2.2. Recruitment process

Interested patients complete a brief initial pre-screener after giving oral consent. If patients are eligible after completing the initial pre-screener, a brief description of the study is provided. Patients are informed that if they are enrolled in this study, their care provider at the clinic will be informed so that they receive integrated care. If interested, patients are scheduled for an in-person screening visit in which the M.I.N.I International Neuropsychiatric Interview 7.0 (31) is administered to assess for diagnostic inclusion/exclusion criteria. If eligible, a detailed description of the study sequences and components is provided and the patient’s ability to provide consent for study participation is assessed. Utilizing iterative feedback, patients are provided with a copy of the consent form and a careful explanation of all aspects and details covered in the written consent. In order to be eligible for study participation, patients have to demonstrate an understanding of study procedures contained in the statement of informed consent after no more than two explanations. Following this process, written informed consent is obtained and clinical staff (patient’s care provider at the psychiatric outpatient clinic) is informed of patient enrollment and a baseline assessment visit is scheduled. Patients receive subway cards worth $11 at the screening visit regardless of study enrollment.

2.3.2.3. Randomization

After the baseline assessment, participants are randomized to receive either SMI-CM or EST. Randomization is stratified by gender and a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Participants are unaware of the assignment until the first in-person counseling session.

2.3.2.4. Comparison condition: Enhanced standard treatment plus non-contingent CM (EST)

Participants assigned to EST receive the same number of individual smoking cessation counseling sessions as SMI-CM (two in-person sessions [35 minutes] and two brief phone sessions [15–20 minutes]), up to 8 weeks of nicotine patches, CO videos submission (with non-contingent incentives), and EMA reports.

2.3.2.4.1. Individual counseling sessions

EST individual session content is identical to SMI-CM except it lacks the mindfulness components. We decided not to match the length of EST individual counseling sessions to SMI-CM in order to compare SMI-CM to realistic smoking cessation interventions.

2.3.2.4.2. Non-contingent incentives for CO video submission (non-contingent CM)

Each participant in the EST group (the non-contingent CO group) is yoked to a single participant in the SMI-CM, similar to the procedure used in Dallery et al. (32). The yoked EST participant earns a similar amount of incentives as long as they submit a sufficient number of CO videos. EST participants are told that submitting a CO video gives them a chance to earn incentives regardless of CO levels (non-contingent), but that the incentives are awarded on an unpredictable schedule. The goal is to ensure that the average amount of money earned by the EST group will be similar to that of the SMI-CM group. All other procedures (submitting CO videos) are the same as in SMI-CM.

2.3.3. Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) reports

As in SMI-CM, participants in the EST group are asked to complete the same frequency of EMAs (5 daily reports) via the smartphone app for 38 days.

2.3.4. Considerations for Comparison Intervention and Study Design

We recognized that if we did not offer nicotine patch and monetary incentives in the EST group and subsequently found an advantage for the SMI-CM condition, we could not rule out the possibility that the effect was due to receiving the nicotine patch or receiving monetary incentives. Therefore, to isolate the effect of SMI-CM, EST participants also receive nicotine patches and monetary compensation. While this makes the control condition more stringent, if we do find any advantage for SMI-CM, we will be confident that the finding is due to the intervention itself (mindfulness training and contingency management). Nevertheless, we acknowledge that our design does not allow us to tease apart the effects of mindfulness training vs. CM. We considered using a three-group design (i.e., mindfulness training with and without CM) plus the EST control. However, a three-group design goes beyond the scope of this developmental project, and we therefore, decided to focus on the efficacy of the mindfulness intervention when combined with CM.

2.3.5. Assessment and compensation

2.3.5.1. Assessment visits

Self-report measures and interview questions are administered at baseline (approximately 14 days prior to target quit date), pre-quit (3 days prior to target quit date), and post-quit follow-up assessments (2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 3 months after target quit date). Assessments are administered by trained undergraduate and bachelors’ level research assistants in private offices at the outpatient psychiatric clinic from which participants are recruited. The study duration for a typical participant is 3.5 months. Participants receive $25, $30, $50, $50, and $50 in prepaid gift cards for each assessment, respectively. A maximum of $205 is provided for completing all 5 assessment visits. For the first in-person counseling visit (without assessment), a subway card valued at $5.50 is provided.

2.3.5.2. EMA

All participants are randomly (at least 1.5 hours apart during participants’ waking hours) prompted by the smartphone app to complete EMA reports 5 times per day. Each report takes about 3–5 minutes to complete. In order to increase adherence, participants receive $.20 for each completed EMA report, up to a total of $38. A bonus of $10 is also provided if participants complete more than 90% of the assessments each week. The maximum total incentives for completing EMA reports is $88 and the earned amount is provided in cash at the 4-week follow-up visit after participants return their study smartphone.

In addition, immediately after the mindfulness practice, participants are prompted to complete a brief post-mindfulness report which takes less than 1 minute to complete. No incentives are provided for post-mindfulness reports in order to avoid inadvertently incentivizing the mindfulness practice.

2.3.6. Adherence and retention

Feedback regarding EMA report adherence is provided to all participants at the beginning of the second counseling session. When participants (both groups) do not complete any practice or reports for 2 consecutive days, a research assistant contacts them to troubleshoot. In addition, if a participant does not submit any CO videos on the first day (target quit date), a research assistant contacts the participant. If the participant is having difficulty, a research assistant reviews the CO video procedure with the participant over the phone.

We also collect contact information for a significant other and/or close friend/family member, and ask participants’ permission to contact their health care providers (e.g., case manager, social worker, therapist/counselor) at the study clinic and other clinics if we are not able to reach them.

2.3.7. Measures

Participants complete self-report measures administered at baseline, 3 days prior to their target quit date (pre-quit), and at 2-week, 4-week, and 3-month follow-up assessments. Participants also provide EMA data directly through the smartphone starting 10 days prior to their target quit date through 4 weeks post-target quit date. See Table 3 for measures and schedule of administration.

Table 3.

Measures and Scheduled Study Visits.

| Measures | # of items |

BL | PQ | 2wk | 4-week | 3-month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking History, Nicotine Dependence, Withdrawals | ||||||

| Demographic Information and Smoking History | ✕ | |||||

| Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) (33) | 6 | ✕ | ||||

| Readiness to Quit Smoking (Readiness Ruler) | 1 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Thoughts About Abstinence (TAA) (35) | 7 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS) (36) | 15 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale (MRSS) (34) | 21 | ✕ | ||||

| Smoking Outcomes | ||||||

| Point Prevalence Abstinence | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | |||

| Timeline Follow-Back (cigarette smoking) (47) | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | |

| Carbon Monoxide | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | |

| Saliva Cotinine | ✕ | |||||

| Mindfulness, Experiential Avoidance, Stress Reactivity | ||||||

| Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (37) | 39 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ) (38) | 7 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS) (39) | 13 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS) (40) | 15 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Perceived Stress Reactivity Scale (PSRS) (41) | 23 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Psychiatric Symptoms and Affect | ||||||

| PROMIS- Depression Short Form 8a (43) | 8 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| PROMIS- Anxiety Short Form 8a (43) | 8 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) (45) | 20 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM) (44) | 5 | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Alcohol and Drug Use | ||||||

| Timeline Follow-Back (alcohol and drug use) (47) | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | |

| Psychiatric and Medical History | ||||||

| Treatment History Interview | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | |

| Qualitative Interview | ||||||

| Qualitative interview | ✕ | |||||

| Ecological Momentary Assessments (5 times/day) | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

PROMIS: Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

BL: baseline, PQ: pre-quit, 2wk: 2-week, 4wk: 4-week, 3m: 3-month

2.3.7.1

Demographic information, smoking history, and smoking related constructs including nicotine dependence (33), reasons for smoking (34), commitment, desire, and expected success/difficulty with abstinence (35), and nicotine withdrawal symptoms (36) are assessed. To examine potential mediators, the general tendency to be mindful in daily life (37), general experiential avoidance (38), smoking-specific experiential avoidance (39), distress tolerance (40), and perceived stress reactivity (41) are assessed. We also assess depression and anxiety (42, 43), the presence and/or severity of manic symptoms (44), and positive and negative affect (45).

2.3.7.2. Adherence to study activities

Participants’ adherence to each of the smartphone-assisted components of the intervention are assessed by calculating the completion rates of mindfulness practice, CO video submission, and EMA reports.

2.3.7.3. Smoking outcomes

Self-reported abstinence in the past 7 days (i.e., 7-day point prevalence abstinence) at each follow-up assessment is biochemically verified by expired carbon monoxide (CO) analysis (≤ 6 ppm) (46). At the 3-month follow-up, saliva cotinine verification (<15ng/ml) is obtained to confirm self-reported abstinence if the participant is not using nicotine replacement therapy.

2.3.7.4. Smoking cessation treatment, alcohol and drug use, and psychiatric and medical history/hospital courses

The timeline follow-back (TLFB) (47) is used to track use of nicotine patch provided as part of the study, as well as other pharmacotherapy and treatments (e.g., counseling) for tobacco cessation that were not provided as part of the study, alcohol and drug use frequency and quantity, and non-smoking related treatments (hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits, outpatient treatment, medication use).

2.3.7.5. Program evaluation

At the 4-week follow-up, participants complete brief evaluations that include questions assessing how helpful they perceive the overall program, counseling sessions, mindfulness practice, and contingency management components with regard to quitting smoking and managing mood on a 5-point scale (1= “Not at all” to 5= “Very much”). In addition, comfort level with the smartphone and difficulty with videotaping are assessed.

2.3.7.6. Brief qualitative interview

At the 4-week assessment, participants complete a semi-structured interview (15 minutes) to provide feedback on their experience with the EST or SMI-CM intervention.

2.3.7.7. Ecological momentary assessment

2.3.7.7.1. Random reports

Via smartphone, all participants complete EMA via smartphone regarding smoking behavior, putative mediators (e.g., mindfulness, experiential avoidance, affect, withdrawal symptoms, craving), motivation, confidence to quit, perceived behavioral control, temptations to smoke, and alcohol and drug use. The reports are equivalent across conditions except that the SMI-CM group receives 2 additional questions regarding mindfulness activities in the first and last report of the day. Research suggests that brief EMA reports yield summary scores with adequate reliability and data regarding the predictive validity of EMA-administered withdrawal scales that are administered have been published (48, 49).

2.3.7.7.2. Post-mindfulness reports (Only SMI-CM group)

Immediately after the mindfulness practice, participants in the SMI-CM condition are prompted to complete a brief report to provide ratings of momentary negative and positive affect, withdrawal symptoms, and craving, as well as location and activity, and feedback on the mindfulness exercise (e.g., perceived effectiveness of the exercise, ability to focus).

2.3.8. Study materials

An Android smartphone with an unlimited talk, text, data plan, and a CO monitor are provided to participants along with a set of earphones. All smartphones and CO monitors are engraved with “Property of Fordham University.” Participants are able to make domestic phone calls and use the internet as desired with the study smartphones. At participants’ request, a research assistant installs requested game apps on the participant’s study smartphone to increase the likelihood that the study phone is being carried at all times during the study. In order to maximize equipment return, payout of the incentives for CM and EMA is contingent upon return of the CO monitor (at 2-week follow-up) and smartphone (at 4-week follow-up), respectively.

2.3.9. Safety protocol

We developed a comprehensive safety protocol for addressing reports of suicidal ideation at study visits that included discouraging communication with research staff via submitted CO videos. If any messages indicating an emergency are received, the research coordinator immediately contacts a PI.

2.3.10. Sample Size Considerations

Due to the preliminary nature of this RCT, we intend to enroll a total of 60 participants (30 in each condition) to ascertain an effect size for SMI-CM. Effect size estimates will include odds ratios for 7-day point-prevalence abstinence (i.e., biochemically verified self-reported abstinence in the past 7 days) rates at 2-week (end of CM), 4-week (end of mindfulness training), and 3-month follow-ups. We recognize that a sample of this size will be able to detect only medium to large effect sizes (OR ≥ 2.5) using generalized estimating equations (with three assessment points)1. However, a sample size of 60 should allow us to perform an initial evaluation of the potential of SMI-CM intervention while staying within the scope of a developmental project. (50)

2.3.11. Data Analysis Plan

2.3.11.1 Smoking outcomes

We will test the efficacy of the intervention on smoking cessation outcome (biochemically verified 7-day point-prevalence abstinence) at the 2-week, 4-week, and 3-month follow-ups using GEE (51, 52), controlling for gender, nicotine dependence, baseline depressive symptoms, and presence of bipolar disorder diagnosis. In addition, other demographic variables that significantly differ between groups will be included as covariates. Next, the linear effect of time-by-group interaction will be included to examine whether group differences vary as a function of time. Odds ratios and number needed to treat (NNT) will also be calculated. Differential changes in average daily cigarette consumption between groups will also be tested using GEE. Missing data will be handled using 3 different techniques including 1) replacing missing outcome as “smoking,” 2) using available data only, and 3) multiple imputation. An additional analysis will be conducted including a diagnosis (depression vs. bipolar) × group interaction to examine potential differential intervention effects across diagnoses.

2.3.11.2 Potential mechanisms

Although conducting formal mediation analysis is not feasible because of the small sample size of this RCT, we will test potential mechanisms of the SMI-CM intervention effect using both visit data and EMA data. First, we will run regression analyses testing the effect of SMI-CM on values of the putative mediators assessed at 2-week (end of CM) and 4-week (end of mindfulness training) visits, controlling for baseline values. Next, we will use EMA data (the within-individuals, repeated data obtained from randomly timed reports and evening reports) during: 1) the first 2 weeks post target quit date (with CM) and 2) the subsequent 2 weeks (without CM) in separate models to examine the effect of SMI-CM on post-quit changes in hypothesized mediators. Specifically, multilevel models will be used where changes in the candidate mediators (e.g., mindfulness, experiential avoidance, stress reactivity, negative affect, and craving) are assessed within subjects and treatment is assessed between subjects. For example, we will examine the extent to which SMI-CM affects changes in experiential avoidance during the 2-week CM period, relative to EST, controlling for baseline levels of experiential avoidance. Similarly, we will test the treatment effect on the short-term associations between internal smoking cues (e.g., craving, negative affect, withdrawal symptoms) and smoking behavior during the 2 post-quit periods with and without CM.

We will also estimate the relationships between putative mediators (the CM and non-CM periods) and smoking abstinence at 2-week, 4-week and 3-month visits, respectively, controlling for treatment and baseline levels of the mediators to determine if they appear to be associated with outcomes in the expected direction. Visit data for the same periods will also be used to examine the mediator-outcome relationships. While power will be limited, these analyses will indicate whether the selected mediators are likely to be (a) influenced by the intervention and (b) associated with smoking outcomes.

3. Results of the open-label pilot feasibility study

As noted earlier, recruitment procedures were equivalent to the RCT, except that in the RCT we loosened the eligibility criteria due to recruitment difficulties. Additional exclusion criteria for the pilot study were 1) bipolar disorder, 2) current (non-nicotine) substance use disorder (without any exceptions), and 3) regular use (“more than 3 times a month”) of other tobacco products or marijuana (vs. “more than 4 days per week” in the RCT).

3.1. Participant characteristics

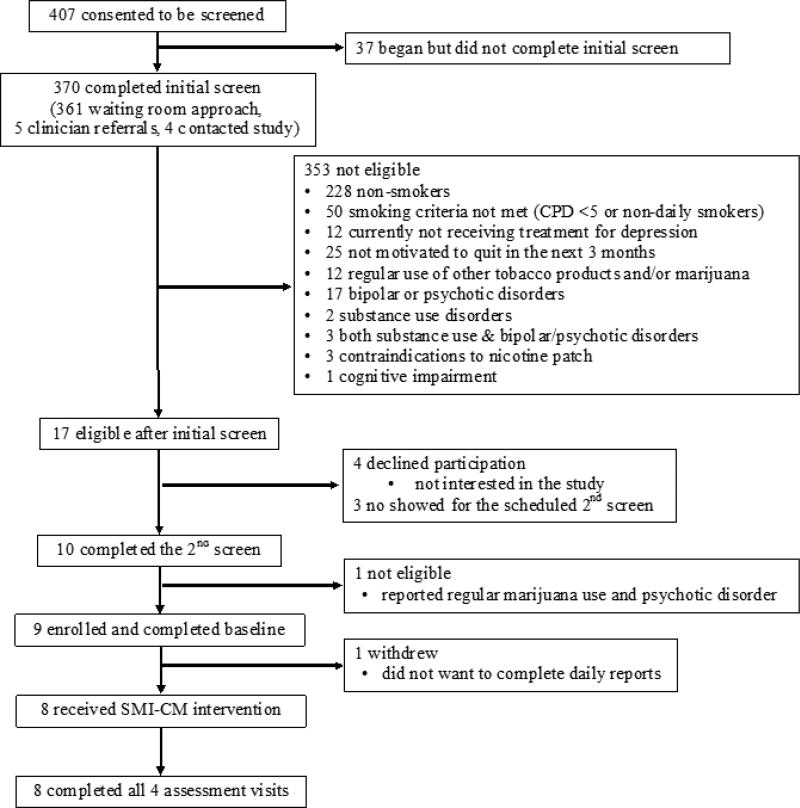

The CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure 1. In total, 9 participants were enrolled and completed the baseline assessment. Of those, 1 dropped out after baseline assessment, leaving 8 participants who initiated SMI-CM.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

All participants (N = 8) were female, 4 (38.5%) were white, 4 (50.0%) were Hispanic, 7 (87.5%) had a high school diploma/GED or less, all reported household incomes of less than $25,000, and 75% were on disability. Three (37.5%) spoke Spanish as their first language. Half (4 of 8) reported only 1 or no prior serious quit attempts and 3 (37.5%) had never used a smartphone or tablet before. Demographic and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Participant Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (N=8).

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Female | 8 (100%) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (50%) | |

| Race | ||

| White or Caucasian | 3 (37.5%) | |

| Black or African American | 4 (50%) | |

| Asian | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Highest Level of Education | ||

| Four-year college | 1 (12.5%) | |

| High School Diploma/GAD | 4 (50%) | |

| Less than High School | 3 (37.5%) | |

| Employment | ||

| Part-time | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Disabled | 6 (75%) | |

| Retired | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Household Income | ||

| Less than $25,000 | 8 (100%) | |

|

| ||

| Mean (SD) | ||

|

| ||

| Age | 55.25 (4.59) | |

| Cigarettes per day | 12.75 (6.88) | |

| Nicotine Dependence (FTCD) | 5.25 (1.91) | |

| Number of Past Serious Quit Attempts | 2.56 (2.19) | |

| Depressive symptoms (PROMIS-D8a) | 23.00 (7.37) | |

| Anxiety symptoms (PROMIS –A8a) | 26.25 (5.15) | |

FTCD: Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence

PROMIS: Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

3.2. Adherence and retention

3.2.1. Individual counseling sessions

All 8 participants received all scheduled individual counseling sessions (2 in-person and 2 phone).

3.2.2. Daily mindfulness practice

Practices lasting less than 3 minutes were excluded from the following statistics. Overall, participants practiced mindfulness 129 times (SD=82) over 38 days (M = 3.4/day). When prompted, participants practiced mindfulness 53% of the time (SD=25.4%) and in addition to the prompted practice, participants, on average, voluntarily practiced mindfulness 29 times (SD=50.6) over 38 days. The most often used recordings were Mindfulness and Cessation (18.1%), Loving Kindness Meditation (12.4%), and Mindfulness and Challenges (11.3%). The least often used recording was Body Scan (1.9%).

3.2.3. CO videos

In total, 68.0% (150 of 220) of requested CO videos were submitted with an average of 18.8 CO videos per participant (M=68.5%, SD=35.0%). A total of 7 participants submitted at least 1 CO video and among those, an average of 12.4 videos (87 videos in total) earned cash incentives (CO ≤ 6 ppm) per participant (M=52.5%, SD=38.8%), making up 58% of overall submitted videos, suggesting that smoking status did not consistently predict video submission. A total of $542, an average of $67.75 per participant (SD=$86.12), was provided to participants as incentives.

3.2.4. EMA reports

Participants completed 72.3% (SD=24.1%) of prompted daily reports, with 97% of reports completed within 30 minutes of the prompt. On average, participants received $45.28 (SD=$27.99) for completing random reports. Overall, 91.0% (938 of 1031) of post-mindfulness reports were completed after the mindfulness practice (≥3 minutes) with an average of 94.1% (SD=7.9%) of prompted post-mindfulness reports completed per participant.

3.2.5 Assessment visits

Follow-up retention was 100% (8/8) at all 4 pre-quit and follow-up visits.

3.3. Smoking cessation outcomes

At each follow-up visit, 1 participant (12.5%) reported biochemically verified (CO ≤ 6 ppm) 7-day point prevalence abstinence. Saliva cotinine level was not tested as the participant reported continued use of nicotine patches. All participants reported reductions in the number of cigarettes smoked per day from baseline (M=12.8, SD=6.9) to 2-week, 4-week, and 3-month post-quit follow-ups (M=2.0, 2.1, 7.2, SD= 2.1, 2.0, 6.2; 84%, 84%, and 46% reduction from baseline, respectively).

3.4. Program evaluations: Participant satisfaction

Participants reported that the program was helpful overall (M=4.88, SD=0.35, on a 5-point scale with 1= “Not at all” and 5= “Very much”) and that they learned helpful skills (M=5.00) and information (M=4.88, SD = 0.35). The mean ratings of helpfulness for the in-person and phone counseling sessions were 4.75 (SD = 0.71) and 4.25 (SD = 1.16), respectively. Participants also reported that daily mindfulness practice was enjoyable (M=4.63, SD=0.74) and helpful for both quitting smoking (M=4.5, SD=1.07), managing mood (M=4.5, SD=0.93), and being mindful in their daily activities (M=4.5, SD=1.07), and that they were likely to continue practicing mindfulness using the recordings in the future (M=4.25, SD=0.71). With regards to the CM component of the program, participants reported that both testing CO and submitting CO videos twice a day (M=4.75, SD=0.46) and receiving incentives for CO less than 7 ppm (M=4.38, SD=0.74) helped with their cessation effort.

Most of the participants reported that they were comfortable working with the smartphone (M=4.25, SD=1.16), with 5 participants endorsing “very much” and 1 “slightly” comfortable. In addition, participants did not find using the CO monitor very difficult (M=2.00, SD=1.20) with 4 participants reporting “not at all” and 1 “moderately” difficult.

3.5. Study materials

All CO monitors were returned. One participant lost her study smartphone and was provided with another smartphone. All other smartphones (including the replacement) were returned.

3.6. Safety monitoring

No adverse events were reported during the study period. The CO videos were not used to communicate any crisis or cases of emergency.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we described 2 phases of a smoking cessation trial conducted at a psychiatric outpatient clinic, including intervention development, study protocol of the currently ongoing preliminary RCT, and results from an open-label pilot feasibility study. The intervention, called smartphone-assisted mindfulness-based intervention with contingency management (SMI-CM), is intended to help smokers with mood disorders currently receiving outpatient psychiatric treatment. The findings from the pilot study indicate high levels of feasibility and acceptability of SMI-CM. Program feedback was very positive and reasonable adherence rates were observed despite the high intensity of the study components (i.e., practicing mindfulness and completing EMA reports 5 times/day and submitting CO videos twice a day), and that 3 of the 8 participants had never used a smartphone before participating in the study.

The pilot study also demonstrated that with brief training and practice sessions augmented by occasional toubleshooting over the phone, all participants, including those who were not familiar or never used a smartphone before, could complete the intervention and study actitvies using the smartphone. Feasibility of the RCT protocol was also demonstrated by high participant retention rates. This high retention rate may, at least partially, be attributable to communications between research staff and participants’ mental health care providers (i.e., counselor, social worker, or psychiatrist), as well as the clinic’s effort to include the research team as part of the clinic to achieve integrated care. At the same time, the generalization of these findings to other populations may be limited as all participants in this feasibility study were low socioeconomic status (household incomes of less than $25,000), and none held full-time jobs; time constraints and value of monetary incentives may differ across different populations.

Only minor changes were made in the study description and instruction, to clarify the study sequences and components. Regarding eligibility criteria, recruitment slowed down after a few months into the RCT phase, and at that point, we relaxed the criteria to include smokers with bipolar disorders and who are in substance use treatment, and to enforce a less restrictive definition of regular use of marijuana and other tobacco use. We acknowledge that increases in the hetrogeneity of the sample will make it more difficult to identify the potential active ingredients of the intervention especially given the small sample size of the RCT. However, less restrictive exclusion criteria may increase generalizability of the findings.

In the RCT, SMI-CM is being tested against a comparison intervention, enhanced standard treatment plus non-contingent CM (EST), that includes the same number of individual smoking cessation counseling sessions (without mindfulness components), daily CO videos submission (with non-contingent incentives), and equivalent EMA reports for achieving smoking cessation. The hypothesized mechanisms of treatment will also be examined. This study may provide valuable information needed to improve smoking cessation rates among smokers with mood disorders, a high-risk population. EMA data from this RCT will also avdance our understanding of dynamic changes in momentary states including affect and craving, in relation to smoking behavior and mindfulness practice assessed in real time.

Acknowledgments

We thank the mental health care providers, administrative staff, and patients at the Montefiore Behavioral Health Center for their invaluable cooperation and support. We are especially grateful to Dr. Elise Richman and Adam Mcgahee for their guidance, which made this project possible.

Funding: The project described is supported by Award Number NIDA grant R34 DA037364 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (PIs: Haruka Minami, Ph.D. and Richard A. Brown, Ph.D.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Calculated using GEEsize (50) with a power of 80% and an alpha of 0.05, assuming Rho (correlation between adjacent time-point) at 0.5 and Psi (a "damping" parameter used to model an attenuated autoregressive correlation structure) at 0.6.

References

- 1.CDC. Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2005–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2016. 2016;65(44):1205–11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes JR. Possible effects of smoke-free inpatient units on psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1993;54(3):109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lising-Enriquez K, George TP. Treatment of comorbid tobacco use in people with serious mental illness. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2009;34(3):E1–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SAMSHA. National Mental Health Services Survey (The N-MHSS Report) Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen S, Marlatt A. Surfing the urge: brief mindfulness-based intervention for college student smokers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(4):666–71. doi: 10.1037/a0017127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis JM, Fleming MF, Bonus KA, Baker TB. A pilot study on mindfulness based stress reduction for smokers. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewer JA, Mallik S, Babuscio TA, Nich C, Johnson HE, Deleone CM, et al. Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: results from a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(1–2):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis JM, Goldberg SB, Anderson MC, Manley AR, Smith SS, Baker TB. Randomized trial on mindfulness training for smokers targeted to a disadvantaged population. Substance use & misuse. 2014;49(5):571–85. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.770025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Myers RE, Karazsia BT, Winton ASW, Singh J. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Mindfulness-Based Smoking Cessation Program for Individuals with Mild Intellectual Disability. International JOurnal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2014;12:153–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vidrine JI, Spears CA, Heppner WL, Reitzel LR, Marcus MT, Cinciripini PM, et al. Efficacy of mindfulness-based addiction treatment (MBAT) for smoking cessation and lapse recovery: A randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(9):824–38. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gluck TM, Maercker A. A randomized controlled pilot study of a brief web-based mindfulness training. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:175. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bricker JB, Bush T, Zbikowski SM, Mercer LD, Heffner JL. Randomized trial of telephone-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation: a pilot study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(11):1446–54. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):613–22. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med. 2008;31(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenzweig S, Greeson JM, Reibel DK, Green JS, Jasser SA, Beasley D. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain conditions: variation in treatment outcomes and role of home meditation practice. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elwafi HM, Witkiewitz K, Mallik S, Thornhill TAt, Brewer JA. Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: moderation of the relationship between craving and cigarette use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130(1–3):222–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brewer JA, Elwafi HM, Davis JH. Craving to Quit: Psychological Models and Neurobiological Mechanisms of Mindfulness Training as Treatment for Addictions. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0028490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouton ME, Westbrook RF, Corcoran KA, Maren S. Contextual and temporal modulation of extinction: behavioral and biological mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):352–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermans D, Craske MG, Mineka S, Lovibond PF. Extinction in human fear conditioning. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigmon SC, Patrick ME. The use of financial incentives in promoting smoking cessation. Preventive medicine. 2012;55(Suppl):S24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tidey JW. Using incentives to reduce substance use and other health risk behaviors among people with serious mental illness. Preventive medicine. 2012;55(Suppl):S54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallagher SM, Penn PE, Schindler E, Layne W. A comparison of smoking cessation treatments for persons with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(4):487–97. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ledgewood DM. Contingency management for smoking cessation: where do we go from here? Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2008;1:340–9. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801030340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wetter D, Vidrine J, Fine M, Rowan P, Reitzel L, Tindle H. Mindfulness-Based Addiction Treatment (MBAT) Manual. 2007 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Brown RA, Emmons KM, Goldstein MG, Monti PM. The Tobacco Dependence Treatment Handbook: A Guide to Best Practices. New York: The Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoops WW, Dallery J, Fields NM, Nuzzo PA, Schoenberg NE, Martin CA, et al. An internet-based abstinence reinforcement smoking cessation intervention in rural smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(1–2):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chau CK, Tu EY, Chan DW, Burnett J. Estimating the total exposure to air pollutants for different population age groups in Hong Kong. Environ Int. 2002;27(8):617–30. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(01)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones AY, Lam PK. End-expiratory carbon monoxide levels in healthy subjects living in a densely populated urban environment. Sci Total Environ. 2006;354(2–3):150–6. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dallery J, Glenn IM, Raiff BR. An Internet-based abstinence reinforcement treatment for cigarette smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(2–3):230–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Bonara LI, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF, Dunbar GC. Reliability and Validity of the M.I.N.I. International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): According to the SCID-P. European Psychiatry. 1997;12:232–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dallery J, Raiff BR, Grabinski MJ. Internet-based contingency management to promote smoking cessation: a randomized controlled study. J Appl Behav Anal. 2013;46(4):750–64. doi: 10.1002/jaba.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berlin I, Singleton EG, Pedarriosse AM, Lancrenon S, Rames A, Aubin HJ, et al. The Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale: factorial structure, gender effects and relationship with nicotine dependence and smoking cessation in French smokers. Addiction. 2003;98(11):1575–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Commitment to abstinence and acute stress in relapse to alcohol, opiates, and nicotine. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1990;58(2):175–81. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43(3):289–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baer RA, Smith GT, Allen KB. Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment. 2004;11(3):191–206. doi: 10.1177/1073191104268029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Waltz T, Zettle RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionniare - II: A revised measure of psychological flexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011;42:676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Antonuccio DO, Piasecki MM, Rasmussen-Hall ML, Palm KM. Acceptance-based treatment for smoking cessation. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35(4):689–705. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29(2):83–102. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlotz W, Yim IS, Zoccola PM, Jansen L, Schulz P. The Perceived Stress Reactivity Scale: measurement invariance, stability, and validity in three countries. Psychol Assess. 2011;23(1):80–94. doi: 10.1037/a0021148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Salsman JM, Butt Z, Moore TL, Lawrence SM, et al. Assessment of self-reported negative affect in the NIH Toolbox. Psychiatry Res. 2013;206(1):88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18(3):263–83. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, Davis JM. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42(10):948–55. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cropsey KL, Trent LR, Clark CB, Stevens EN, Lahti AC, Hendricks PS. How low should you go? Determining the optimal cutoff for exhaled carbon monoxide to confirm smoking abstinence when using cotinine as reference. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(10):1348–55. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12(2):101–12. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Life before and after quitting smoking: an electronic diary study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(3):454–66. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Lawrence DL, Jorenby DE, Shiffman S, Baker TB. Psychological mediators of bupropion sustained-release treatment for smoking cessation. Addiction. 2008;103(9):1521–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dahmen G, Rochon J, Konig IR, Ziegler A. Sample size calculations for controlled clinical trials using generalized estimating equations (GEE) Methods Inf Med. 2004;43(5):451–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeger SL, Liang K-Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]