Abstract

Objective

We sought to examine whether patients with focal epilepsy exhibit sleep dependent memory consolidation, whether memory retention rates correlated with particular aspects of sleep physiology, and how the process was affected by seizures.

Methods

We prospectively recruited patients with focal epilepsy and assessed declarative memory using a task consisting of 15 pairs of colored pictures on a 5 × 6 grid. Patients were tested 12 hours after training, once after 12 hours of wakefulness and once after 12 hours that included sleep. EMG chin electrodes were placed to enable sleep scoring. The number and density of sleep spindles were assessed using a wavelet-based algorithm.

Results

Eleven patients were analyzed age 21–56 years. The percentage memory retention over 12 hours of wakefulness was 62.7% % and over 12 hours which included sleep 83.6 % (p = 0.04). Performance on overnight testing correlated with the duration of slow wave sleep (SWS) (r=+0.63, p <0.05). Three patients had seizures during the day, and another 3 had nocturnal seizures. Day-time seizures did not affect retention rates, while those patients who had night time seizures had a drop in retention from an average of 92% to 60.5%.

Conclusions

There is evidence of sleep dependent memory consolidation in patients with epilepsy which mostly correlates with the amount of SWS. Our preliminary findings suggest that nocturnal seizures likely disrupt sleep dependent memory consolidation.

Significance

Findings highlight the importance of SWS in sleep dependent memory consolidation and the adverse impact of nocturnal seizures on this process.

Keywords: Epilepsy, declarative memory, Sleep, Seizures, Memory consolidation

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurologic conditions with active disease present in almost 7 out of 1000 people in the U.S. (Theodore, et al. 2006). The consequences of epilepsy can be quite debilitating with regard to cognitive, psychiatric, and psychosocial aspects of life (Berg. 2011,Schachter. 2006). Memory complaints are especially prevalent in individuals with epilepsy and can be more debilitating than the seizures themselves (Aldenkamp and Arends. 2004). Traditionally, memory testing for epilepsy patients has consisted of neuropsychological assessments within a single session over several hours. However, new forms of memory deficits were uncovered with serial testing over days to weeks; a phenomenon termed “accelerated long term forgetting” which has been shown to have a strong association with epilepsy (Fitzgerald, et al. 2013).

The role of sleep in memory processing and consolidation has been highlighted in a number of studies (Stickgold. 2005). Memories, once encoded, are subsequently stabilized, enhanced, elaborated and integrated into existing memory networks. The hippocampus plays a central role in the acquisition of new memories which over time become encoded in neocortical regions (Hasselmo and McClelland. 1999). Memory enhancement, at least for motor and visual discrimination, has been shown to be a sleep-dependent process (Stickgold and Walker. 2005). The important components of sleep that seem to be involved in the processing of memories include sleep spindles and the duration slow wave sleep (SWS) (Stickgold. 2005). Studies assessing memory consolidation in epilepsy patients have been limited. In one of the few studies in adult patients, verbal memory consolidation was been shown to correlate with SWS (Deak, et al. 2011). Studies analyzing children with focal epilepsy have highlighted an impairment in sleep dependent memory consolidation and the adverse impact of interictal epileptiform discharges (Sud, et al. 2014,Galer, et al. 2015). Given the limited data available in adults and some conflicting data in children, it would be especially useful to determine whether there is evidence of memory consolidation in the epilepsy monitoring unit to understand the phenomenon better and evaluate factors which may have an influence on this process.

In the current study, we investigated whether there was evidence of sleep dependent memory consolidation in adults with focal epilepsy admitted to the epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU). We tested whether their overnight memory performance correlated with the number of spindles as well as sleep stage duration (N2 and SWS); with repeated testing. We also investigated potential effects of seizures on memory performance.

2. Methods

2.1 Cohort Selection

Consecutive patients with focal epilepsy were recruited prospectively over a period of 2 years from the EMU at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Inclusion criteria were: 1) adults 18 –60 years old, and 2) diagnosis of focal epilepsy by history and EEG. Exclusion criteria were: 1) EMU stays of less than 3 days, 2) history of obstructive sleep apnea or other known primary sleep disorder, 3) daily use of barbiturates or benzodiazepines, 4) prior cranial surgery, 5) inability to exhibit a greater than 40% retention rate on the memory task, 6) known active alcohol or drug use, or 7) diagnosis of a neurodegenerative condition. Data collected included patient demographics, seizure medications at the time of testing, and epilepsy characteristics. The study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital institutional review board.

2.2 EEG and sleep scoring

Subjects recruited for this study underwent inpatient continuous video-EEG monitoring for clinical indications with the aim of capturing their habitual seizures. The conventional 10–20 system electrode placement was used with the addition of anterior temporal (T1,T2) leads to localize the area of ictal onset. EEG data were sampled at 256 Hz. In order to score sleep, additional submental electrodes were added. The T1, T2 electrodes were used for electrooculography. The overnight EEG recording was scored for sleep stages and for arousals using standard guidelines (Iber. 2007).

2.3 Nonverbal memory task

The memory task was a 2-D object-location memory task similar to the children’s game “Concentration.” It consisted of 15 pairs of colored pictures showing different animals and every-day objects. Each pair contained identical pictures of one item. All 30 possible spatial locations were shown and used as grey squares (“the back of the cards”) on a 15 inch laptop screen. The locations were geometrically ordered in a checkerboard-like 5 × 6 matrix. At learning, the first card of each card-pair was presented alone for one second followed by the presentation of both cards for three seconds. After an interstimulus interval of three seconds, the next card-pair was presented in the same way. The entire set of card pairs was presented twice in different orders. Immediately after these two exposures, recall of the spatial locations was tested using a cued recall procedure, i.e., the first card of each pair was presented and the subject was asked to indicate the location of the second card with a computer mouse. Visual feedback was given in each case by presenting the second card at the correct location for two seconds independent of whether the response was correct or not, to enable re-encoding of the correct location of the card-pair. After presenting a card-pair, both cards were replaced by grey squares again, so that the probability of being correct if guessing remains the same throughout each run. The cued recall procedure was repeated until the subject reached a criterion of 40% correct responses. Once subjects achieved the criterion of at least 40% correct, they were tested one last time without any feedback, and the number of card pairs recalled was considered their baseline. Retention rates were calculated as number of correct card pairs recalled after 12 hours/baseline correct card pairs.

Subjects were tested on the recall procedure a maximum of 8 times, after which, if criterion was not reached, the subject’s participation in the study was terminated.

2.3 Study Protocol

Subjects were recruited upon admission and testing was started the following day to avoid any ‘first night effect’ (transient sleep structure changes provoked by sleeping in an unfamiliar environment). For each subject, there was a daytime session (7:00–9:00) and an evening session (19:00–21:00).

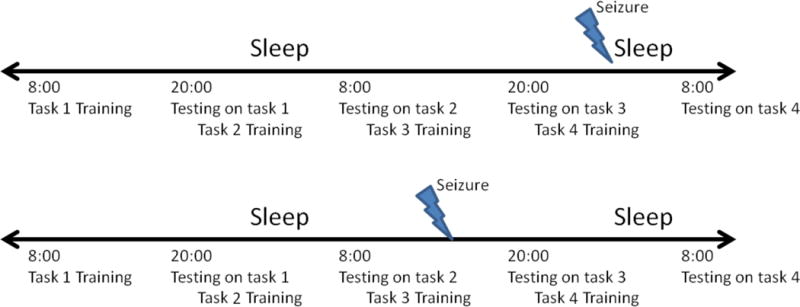

During the first session, subjects were ‘trained’ on a single set of cards. With subsequent sessions, they were first tested on the set on which they trained 10–14 hours prior, and then trained on a new set (figure 1). Subjects were advised to refrain from caffeine, and avoid daytime naps, and they were provided with earplugs to attenuate surrounding noise during sleep. Testing was stopped if the subject was sleep deprived, experienced a focal dyscognitive seizure (with or without secondary generalization), or after 4 days of testing. Prior to each session, the subject filled out the Stanford Sleepiness Score (Hoddes, et al. 1973), a measure of subjective sleepiness, to monitor the effect of sleepiness on the memory task.

Figure 1.

Study protocol and possible seizure scenarios

2.4 Sleep spindle detection

To calculate sleep spindle measures, overnight N2 and SWS data was preprocessed and analyzed using MatLab R2013b (The MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts) software. Manual rejection of artifact was performed visually. To detect discrete spindle events, a wavelet based algorithm (Wamsley, et al. 2012) was used. The raw EEG signal was subjected to a time-frequency transformation using an 8-parameter complex Morlet wavelet. Spindles were detected at each EEG channel by applying a thresholding algorithm to the extracted wavelet scale corresponding approximately to the 10 Hz - 16 Hz frequency range. For thresholding, the rectified moving average of the signal was first calculated, using a 100-millisecond sliding window. A spindle event was identified whenever this wavelet signal exceeded threshold (defined as 4.5 times the mean signal amplitude of all artifact-free epochs) for a minimum of 400 milliseconds; this method has been validated in prior studies (Wamsley, et al. 2012). The spindle counts were obtained for each individual electrode and then averaged.

For subjects who did not have seizures, the first night of testing was analyzed. For patients with seizures, sleep during the 24 hour seizure-free period immediately preceding the seizure was used as the control.

2.5 Statistical analysis

A paired t-test was used to compare performance between testing after12 hours of wakefulness and testing after 12 hours that included sleep after normality of retention scores was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Pearson’s correlation was then used to identify any correlation between overnight retention and total sleep spindle count (N2 and SWS), spindle density (N2 and SWS), and duration of N2 and of SWS. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 11.0 (SAS).

3.0 Results

3.1 Clinical characteristics of the cohort

A total of 17 patients consented to the study. Six patients were subsequently excluded: four were unable to achieve a ≥40% retention rate during training, and two withdrew due to discomfort from the chin leads. The clinical characteristics of the remaining 11 subjects are summarized in Table 1. A single subject’s overnight sleep could not be analyzed due to excessive electrode artifact and was not included in the analysis of sleep spindles and SWS duration.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the cohort

| Clinical Characteristics | |

|

| |

| Female | 45% |

|

| |

| Race | Caucasian 63% |

| Hispanic 37% | |

|

| |

| Average age at testing in years (range) | 39.7 (21.7 to 55.7) |

|

| |

| Average epilepsy duration in years | 15.6 (2.4 – 33.9) |

|

| |

| Average monthly frequency of dyscognitive seizures (range) | 3.3 (0–12) |

|

| |

| Epilepsy Localization | Right temporal (18%) |

| Right Frontal (9%) | |

| Left Frontotemporal/temporal (73%) | |

|

| |

| MRI findings | Normal (54%) |

| Cavernoma (9%) | |

| Mesial temporal sclerosis (9%) | |

| Low grade Glioma (9%) | |

| Heterotopia (9%) | |

| Dual Pathology (9%) | |

3.2 Sleep-dependent memory consolidation

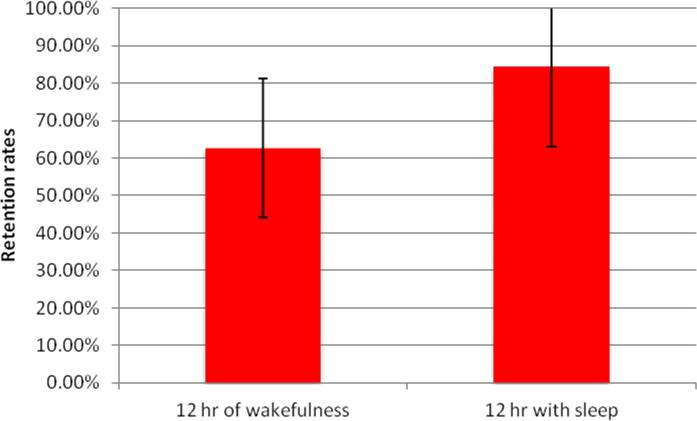

The average percentage memory retention over 12 hours of wakefulness was 62.7% (±18.5% S.D.), and over 12 hours that included sleep was 83.6 % (±21.5% S.D.), p = 0.0396 (figure 2). Subject 6′s daytime retention rate was unavailable for the night analyzed and was not included in the comparison. Average Stanford Sleepiness Scale scores after 12 hours of wakefulness was 3.18 (1–4) and after sleep 2.91 (1–4). Data regarding sleep stage duration and medications administered over the 24 hours of testing are included in Table 2. A single subject’s retention rate was 120%; the subject had correctly encoded 6 card pairs after training, but only 5 pairs on immediate testing unlike other subjects who either remained the same or improved their score. The subject recalled 6 correct card pairs after a night of sleep.

Figure 2.

Retention rates over 12 hours of wakefulness, and 12 hours with sleep.

Table 2.

Study night characteristics

| Retention (%) | N1 (min) | N2 (min) | N3 (min) | REM (min) | Total Sleep time (Hours) | Antiseizure medications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 120 | 51 | 292 | 67 | 19 | 7.15 | Levetiracetam, topiramate |

| 2 | 100 | 64 | 235 | 30 | 53 | 6.65 | Levetiracetam |

| 3 | 70 | 21 | 269 | 42 | 52 | 6.38 | Valproic acid |

| 4 | 100 | 52 | 290 | 52 | 84 | 7.93 | Lamotrigine, Carbamazepine |

| 5 | 75 | 49 | 138 | 29 | 40 | 4.25 | None |

| 6 | 100 | 121 | 234 | 11 | 43 | 6.81 | None |

| 7 | 60 | 14 | 177 | 16 | 61 | 4.45 | None |

| 8 | 75 | 41 | 194 | 14 | 70 | 5.31 | Lamotrigine, Valproic acid |

| 9 | 85.7 | 46 | 146 | 43 | 53 | 4.78 | Lamotrigine |

| 10 | 50 | 66 | 326 | 7 | 63 | 7.69 | Valproic acid |

| 11 | 100 | 44 | 243 | 27 | 46 | 5.99 | Oxcarbazepine |

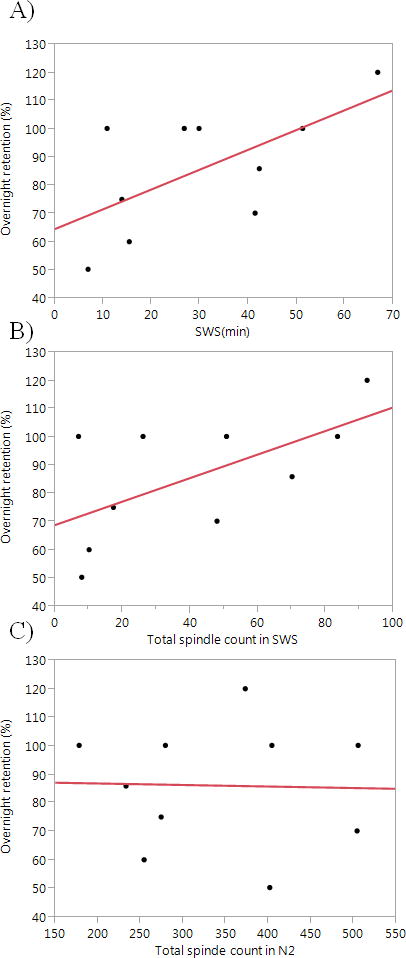

There was a correlation between retention rates and the amount of SWS (in minutes), as well as a trend towards correlation of retention rates and number of sleep spindles in SWS, but not with sleep spindles in N2 (Figure 3) or with duration of N2. No correlation was found between retention rates and N2 or SWS spindle density.

Figure 3.

Correlations between percentage retention rates after a night of sleep and A) SWS duration (r= +0.63, p = 0.049) B) total spindle counts in SWS (r= +0.62, p= 0.057) C) total spindle count in N2 sleep (r= −0.03, p >0.5)

Using a different approach of data analysis, we re-assessed the correlations using the change score (night time retention - daytime retention) rather than then the ratio and found a similar positive correlation with SWS in minutes (r=+0.67, p=0.04), and number of spindles in SWS (r=+0.68, p=0.035).

3.3 Effects of seizures

Three subjects had seizures during the 12 hours of wakefulness (1 had a right temporal focal seizure and a separate generalized tonic clonic (GTC) seizure, the other 2 each had 1 left fronto-temporal/temporal seizures). Average memory retention for the 3 subjects was 62.5% with no seizures and 71% with seizures. Interestingly, the patient with both a focal and a separate GTC seizure still achieved 83% retention.

Three subjects had seizures during sleep (1 had 3 right temporal focal dyscognitive seizures, 1 had 1 left temporal dyscognitive seizure, and 1 had a GTC seizure of left temporal onset). Average overnight retention for the 3 subjects was 91.7% with no seizures and 60.5% with seizures. Subject 2 had seizures during the daytime and then seizures during the night. A summary of seizure details and effect on sleep are listed in table 3.

Table 3.

Details about retention rates and sleep in patients with seizures, and the day of seizure occurrence during their admission.

| Patients with daytime seizures | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl retention | Sz retention | Sz on day# | Sz timing (after training in hrs) | Sz timing (before testing in hrs) | Total sleep time ctrl (hrs) | Total sleep after sz (hrs) | Ctrl N3 (min) | Sz N3 (min) |

| 50 | 83.33 | 3 | GTC (4), FD(5) | −7, −6 | 6.65 | 5.72 | 29.9 | 23.8 |

| 75 | 75 | 3 | FD(8) | −3 | 7.93 | 7.0 | 51.5 | 33.5 |

| 62.5 | 54.5 | 4 | FD(2) | −9 | 4.78 | X | 43 | X |

| Patients with seizures during sleep | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl retention | Sz retention | Sz on day# | Sz timing (after training in hrs) | Sz timing (before testing in hrs) | Sz timing (after sleep in hrs) | Total sleep ctrl night (hrs) | Total sleep sz night (hrs) | Ctrl N3 (min) | Sz N3 (min) | N3 (min) prior to sz |

| 100 | 40 | 3 | FD (9,10,11) | −1,−2,−3 | 5,6,7 | 6.65 | 5.72 | 29.9 | 23.8 | 23.8 |

| 75 | 70 | 3 | FD (2) | −9 | 1 | X | 4.26 | X | 58 | 0 |

| 100 | 71 | 4 | GTC (3) | −9 | 1 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 27 | 51.5 | 51.5 |

Ctrl = control, FD = focal dyscognitive, GTC= generalized tonic clonic, Hrs= hours, min = minutes, Sz= seizure.

The day# is in relation to the patient’s admission (e.g. day# 3 is the third day of admission and includes an initial 12 hour epoch of wakefulness starting between 7:00–9:00 followed by another 12 hour epoch with sleep starting between 19:00–21:00 – a seizure during this latter epoch is still labelled as day#3). One patient’s post-seizure sleep EEG was unavailable and one patient’s control night could not be analyzed due to electrode artifact. X signifies that the data is unavailable.

4.0 Discussion

This study provides two significant contributions to our current understanding of sleep and memory in patients with epilepsy. It reveals evidence of sleep-dependent memory consolidation in epilepsy patients admitted to the EMU, and that the consolidation correlates with the amount of SWS overnight. A trend toward correlation of consolidation with the amount of sleep spindles during SWS was also observed. Secondly, our study provides preliminary data as evidence that seizures significantly reduce this consolidation.

Slow waves are the most prominent feature of SWS and consist of alternating down states of hyperpolarization and up states of depolarization, the latter accompanied by prominent faster frequency oscillations including sleep spindles (Piantoni, et al. 2013). The spindles occurring during the slow oscillations have been postulated to play a role in memory consolidation (Molle, et al. 2011), and the transition of memories from a hippocampus-dependent state to more widespread cortical networks (Frankland and Bontempi. 2005,Hasselmo. 1999). The slow wave oscillations allow functional coupling of distributed cortical networks and facilitate cortico-cortical communication (Cox, et al. 2014). The synaptic homeostasis theory for sleep dependent memory consolidation also posits a central role for SWS by facilitating synaptic reorganization and changes in synaptic strengths (Tononi and Cirelli. 2014). During SWS, protein synthesis required for long-term potentiation also appears to be increased (Poe, et al. 2010).

Our findings are consistent with prior studies on visuospatial consolidation in sleep. Studies analyzing declarative memory in healthy volunteers revealed improvement in visuospatial navigation of a maze after a night of sleep (Nguyen, et al. 2013). Peigneux et al. showed that the extent of increase in regional hippocampal blood flow during SWS correlated with improved overnight performance on a navigation task (Peigneux, et al. 2004). Other investigators have demonstrated enhanced memory consolidation using odor cues but only when the cues were provided during SWS (Rasch, et al. 2007).

Only a handful of prior studies have addressed memory consolidation in epilepsy in particular. In a study of adults with temporal lobe epilepsy, there was evidence of accelerated forgetting during wakefulness, and evidence of a correlation on verbal memory performance with percentage of SWS (Deak, et al. 2011). In children with idiopathic focal epilepsy, overnight performance on a visuospatial task was worse than in healthy controls, and was even further worse in those with a higher calculated spike wave index, but poor performance did not correlate with antiseizure medications (Galer, et al. 2015). In another study of children with medically refractory epilepsy in the EMU, there was no evidence of overnight consolidation on a verbal task (Sud, et al. 2014). The discrepancy between some of our findings and those of prior studies may be related to the setting, the task being tested (verbal v.s. nonverbal), and the degree of interictal abnormalities. In general, adults with epilepsy tend to have a lower number of sleep-potentiated interictal discharges as compared to children, especially those with idiopathic focal epilepsy (Sanchez Fernandez and Loddenkemper. 2012) which is why we did not analyze the burden of interictal discharges.

The relationship between sleep and epilepsy is complex. Patients with temporal lobe epilepsy have decreased sleep efficiency (Crespel, et al. 2000) even in the absence of seizures, and patients with epilepsy in general have less SWS and sleep spindles (Declerck, et al. 1982). In addition, certain antiseizure medications have been shown to affect sleep architecture with some evidence for a decrease in SWS with lamotrigine and benzodiazepines, and an increase with gabapentin (Bazil. 2003). How antiseizure medication affects memory consolidation is in need of further research. Galer’s study did not find any effect in children (Galer, et al. 2015). In light of our findings, interventions to enhance the amount of SWS may be of importance in this patient population given the prevalence of memory complaints.

We also provide some interesting preliminary findings on the effect of seizures on memory consolidation. For example, one of our subjects with a single daytime right temporal seizure and then another daytime GTC seizure showed very good retention of visuospatial memory suggesting that the information acquired was resistant to the seizure effects and could still be retrieved. The most prominent effects on consolidation were noted in subjects who had seizures during sleep. We suspect that the significant impairment in consolidation seen after seizures that occurred in sleep is multifactorial, involving the effects of seizures themselves on brain function, sleep architecture, as well as the length of the post-ictal state.

The pathophysiology of the post-ictal state is unclear but likely involves cortical spreading depression, neurotransmitter changes and alterations in cerebral blood flow (Fisher and Schachter. 2000). Haelmstaedter (1994) assessed 31 patients with dyscognitive and secondarily generalized seizures using a paradigm consisting of verbal list and block design recall up to one hour after a seizure. They showed preferential changes in memory deficits depending on site of seizure onset, even after the patients were thought to have recovered clinically from their seizure. There is also evidence that nocturnal seizures may have a significant disruption on sleep architecture and increase stage 1 sleep while reducing stage 4 and REM sleep (Bazil, et al. 2000). Studies in animals have also documented cognitive changes post-ictally. Lin et al. (2009), tested rats with a spatial accuracy task at baseline, during 11 days of induced convulsions, and after a recovery period of 9 days. They were able to show a progressive decline in performance during the seizure days, and gradual improvement during the recovery period. Impairments in the task were also obvious one day after the seizure and prior to the induction of a second seizure. The authors hypothesized that adequate amounts of sleep facilitated the recovery. Boukherza et al. (2003) tested rats in a water maze up to an hour after flurothyl-induced generalized seizures; they found post-ictal impairments in spatial memory in the rats, with worse performance by rats with prior injuries. Thus, there seems to be compelling evidence for the direct effects of seizures on cognition during the post-ictal phase and disruption of sleep architecture. Further studies are needed to assess the interaction between these interictal and ictal changes in epilepsy and their impact on sleep and memory consolidation.

Our study has a number of limitations, primarily its small sample size which does not allow for an adequate analysis of the impact of seizure lateralization on cognitive performance in memory consolidation. Right hemispheric epilepsy for example was underrepresented in our cohort. We were also unable to assess the impact of seizure frequency, spread, and timing with relation to testing. In addition, the EMU is a novel, stressful environment for patients where they undergo rapid medication changes, and we cannot adequately assess its impact on performance. The impact of serial testing in this setting and the possibility of one task interfering with the other is unclear.

The small sample size also does not allow corrections for multiple correlations and we cannot rule out that some of the findings are due to chance alone. It is however encouraging that the findings are consistent with the literature. The advantages of our study include a standardized method of evaluation of both sleep and memory type, and continuous monitoring which allows strict evaluation of sleep duration as well as continuity of wakefulness prior to the task training and retesting.

5.0 Conclusion

Our results reveal that patients with focal epilepsy exhibit evidence of sleep dependent memory consolidation in the EMU, and this directly correlates with the amount of SWS. We provide preliminary evidence that nocturnal seizures may have an adverse effect on this process.

Highlights.

Patients with epilepsy were tested serially on a visuospatial task

Retention rates were higher after 12 hrs with sleep v.s 12 hrs of wakefulness

Overnight retention best correlated with duration of slow wave sleep

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest to be disclosed

References

- Aldenkamp AP, Arends J. Effects of epileptiform EEG discharges on cognitive function: is the concept of “transient cognitive impairment” still valid? Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5(Suppl 1):S25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazil CW. Effects of antiepileptic drugs on sleep structure : are all drugs equal? CNS Drugs. 2003;17:719–728. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazil CW, Castro LH, Walczak TS. Reduction of rapid eye movement sleep by diurnal and nocturnal seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:363–368. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AT. Epilepsy, cognition, and behavior: The clinical picture. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl 1):7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukhezra O, Riviello P, Fu DD, Lui X, Zhao Q, Akman C, et al. Effect of the postictal state on visual-spatial memory in immature rats. Epilepsy Res. 2003;55:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(03)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R, van Driel J, de Boer M, Talamini LM. Slow oscillations during sleep coordinate interregional communication in cortical networks. J Neurosci. 2014;34:16890–16901. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1953-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespel A, Coubes P, Baldy-Moulinier M. Sleep influence on seizures and epilepsy effects on sleep in partial frontal and temporal lobe epilepsies. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111(Suppl 2):S54–9. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak MC, Stickgold R, Pietras AC, Nelson AP, Bubrick EJ. The role of sleep in forgetting in temporal lobe epilepsy: a pilot study. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;21:462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declerck AC, Wauqier A, Sijben-Kiggen R, Martens W. In: A normative study of sleep in different forms of epilepsy. Sterman MB, Shouse MN, Passouant P, editors. New York: Academic; 1982. pp. 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS, Schachter SC. The Postictal State: A Neglected Entity in the Management of Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1:52–59. doi: 10.1006/ebeh.2000.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald Z, Mohamed A, Ricci M, Thayer Z, Miller L. Accelerated long-term forgetting: a newly identified memory impairment in epilepsy. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1486–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, Bontempi B. The organization of recent and remote memories. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:119–130. doi: 10.1038/nrn1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galer S, Urbain C, De Tiege X, Emeriau M, Leproult R, Deliens G, et al. Impaired sleep-related consolidation of declarative memories in idiopathic focal epilepsies of childhood. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;43:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME. Neuromodulation: acetylcholine and memory consolidation. Trends Cogn Sci. 1999;3:351–359. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, McClelland JL. Neural models of memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:184–188. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C, Elger CE, Lendt M. Postictal courses of cognitive deficits in focal epilepsies. Epilepsia. 1994;35:1073–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddes E, Zarcone V, Smythe H, Phillips R, Dement WC. Quantification of sleepiness: a new approach. Psychophysiology. 1973;10:431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1973.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iber C. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Holmes GL, Kubie JL, Muller RU. Recurrent seizures induce a reversible impairment in a spatial hidden goal task. Hippocampus. 2009;19:817–827. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molle M, Bergmann TO, Marshall L, Born J. Fast and slow spindles during the sleep slow oscillation: disparate coalescence and engagement in memory processing. Sleep. 2011;34:1411–1421. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen ND, Tucker MA, Stickgold R, Wamsley EJ. Overnight Sleep Enhances Hippocampus-Dependent Aspects of Spatial Memory. Sleep. 2013;36:1051–1057. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peigneux P, Laureys S, Fuchs S, Collette F, Perrin F, Reggers J, et al. Are spatial memories strengthened in the human hippocampus during slow wave sleep? Neuron. 2004;44:535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantoni G, Astill RG, Raymann RJ, Vis JC, Coppens JE, Van Someren EJ. Modulation of gamma and spindle-range power by slow oscillations in scalp sleep EEG of children. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013;89:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poe GR, Walsh CM, Bjorness TE. Cognitive neuroscience of sleep. Prog Brain Res. 2010;185:1–19. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasch B, Buchel C, Gais S, Born J. Odor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidation. Science. 2007;315:1426–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.1138581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Fernandez I, Loddenkemper T. Pediatric focal epilepsy syndromes. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;29:425–440. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31826bd943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter SC. Quality of life for patients with epilepsy is determined by more than seizure control: the role of psychosocial factors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6:111–118. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature. 2005;437:1272–1278. doi: 10.1038/nature04286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R, Walker MP. Memory consolidation and reconsolidation: what is the role of sleep? Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sud S, Sadaka Y, Massicotte C, Smith ML, Bradbury L, Go C, et al. Memory consolidation in children with epilepsy: does sleep matter? Epilepsy Behav. 2014;31:176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodore WH, Spencer SS, Wiebe S, Langfitt JT, Ali A, Shafer PO, et al. Epilepsy in North America: a report prepared under the auspices of the global campaign against epilepsy, the International Bureau for Epilepsy, the International League Against Epilepsy, and the World Health Organization. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1700–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep and the price of plasticity: from synaptic and cellular homeostasis to memory consolidation and integration. Neuron. 2014;81:12–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamsley EJ, Tucker MA, Shinn AK, Ono KE, McKinley SK, Ely AV, et al. Reduced sleep spindles and spindle coherence in schizophrenia: mechanisms of impaired memory consolidation? Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]