Abstract

Residual kidney function (RKF) in patients on dialysis is strongly associated with survival and better quality of life. Assessment of kidney function underlies the management of patients with chronic kidney disease prior to dialysis initiation. However, methods to assess RKF after dialysis initiation are just now being refined. In this review, we discuss the definition of RKF and methods for measurement and estimation of RKF, highlighting the unique aspects of dialysis that impact these assessments.

Keywords: Residual kidney function, total kidney function, glomerular filtration rate, small solute clearance, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, β-trace protein, β-2 microglobulin, cystatin C

Introduction

There is a continuum of kidney function throughout the course of acute and chronic kidney disease. At late stages of kidney disease, loss of excretory, endocrine and metabolic functions of the kidney contribute to signs and symptoms of uremia, requiring replacement of kidney function to preserve health. In patients receiving kidney replacement therapy, the remaining function of the kidney is referred to as the residual kidney function (RKF). In the following sections, we will discuss a definition of RKF, relevance of RKF in patients on dialysis, followed by methods for RKF measurement and estimation.

Definition of RKF

RKF is the kidney function in patients receiving kidney replacement therapy for kidney failure. Conceptually, “total kidney function” is the sum of RKF and the function provided by kidney replacement therapy (Figure 1). In principle, it would be optimal to quantify total kidney function as the sum of RKF and function provided by kidney replacement therapy, and to express each component of RKF in the same units used in earlier stages of kidney disease. While RKF may be present in patients with acute kidney failure and in kidney transplant recipients, we will limit our discussion to patients with chronic kidney failure receiving dialysis. The concept of “total small solute clearance” as a component of “total kidney function” might be particularly useful for patients with chronic kidney failure during the transition to dialysis. Although these concepts are appealing as a unifying metrics, there are theoretical and methodological challenges to this approach.

Figure 1. Total Kidney Function – A New Conceptual Framework to Assess Kidney Replacement Therapies.

A conceptual framework for assessing total kidney function in patients treated with kidney replacement therapies. The total function is a sum of residual kidney function plus the function provided by kidney replacement therapies. Total small solute clearance is a component of total kidney function and is the sum of small solute clearance by glomerular filtration, tubular secretion and kidney replacement therapy.

Theoretical limitations include the following: First, although it is generally accepted that glomerular filtration rate (GFR) provides the best assessment of the overall kidney function in health and disease, there are important kidney functions in addition to glomerular filtration, including other excretory functions (reabsorption and secretion), endocrine and metabolic functions. While the decline in GFR in acute and chronic kidney disease generally parallels the decline in other kidney functions, impairment in other functions may contribute importantly to signs and symptoms of uremia at very low GFR, requiring separate assessment and treatment. For example, deficiencies of hormones produced by the kidney, vitamin D and erythropoietin, can be replaced, ameliorating secondary hyperparathyroidism and anemia. Salt and water retention can be treated by diuretics, ameliorating fluid overload.

Second, while glomerular filtration is the primary mechanism for excretion of many small solutes (molecular weight <500 Da), retention of larger solutes normally excreted by the kidney may also contribute to the burden of illness. In particular, recent attention has focused on solutes that are excreted predominantly by tubular secretion1,2, whose serum levels may rise disproportionately to the reduction in GFR. Some of these “secretion markers” are protein-bound and not removed by dialysis to the same extent as urea.3,4 Other small solutes are considered “sequestered” as they are not in rapid equilibrium with the plasma volume and thus are not efficiently removed by intermittent dialysis. Although dialysis dosing has traditionally focused on urea clearance as a surrogate for all small solute clearance, monitoring the serum levels of secreted and sequestered solutes in addition to filtered solutes may also aid in patient assessment.

Third, methodologically, it may be difficult to reliably quantify the level of GFR at very low values using the same techniques used at higher levels of kidney function. Intermittent dialysis removes some filtration markers, leading to non-steady state serum concentrations, and endogenous extra-renal elimination of filtration markers by the liver, intestines or other organs is often not well quantified.

Notwithstanding these limitations, defining the “total small solute clearance” for patients treated by dialysis as the sum of small solute clearance provided by glomerular filtration, tubular secretion and dialysis is essential to provide a basis to personalize the management of uremia treated with dialysis. In addition, the concept of total kidney function can highlight aspects of current therapies that are adequate, such as clearance of urea, and other aspects that need improvement.

Relevance to incident end-stage renal disease

End-stage renal disease (ESRD), defined in the U.S. as chronic kidney failure treated by dialysis or transplantation, is an important public health problem with high prevalence and cost.5 Over 100,000 patients start dialysis for ESRD in the U.S. every year but face a grim prognosis.5 Approximately 20–25% of the patients starting dialysis do not survive first year on dialysis and only 50% survive more than 3 years.5 Despite many advances in the general medical care of the patients, survival on dialysis has improved minimally over the past three decades. Reducing this first-year risk of death in dialysis patients is listed as a Healthy People 2020 goal6 – but appears unlikely to be achieved in the next 3 years. In addition to the high risk of death, quality of life on dialysis also remains dismal with patients experiencing myriad of symptoms, including those from uremia.7,8

RKF in patients on dialysis is strongly associated with survival. Among patients treated with peritoneal dialysis, reanalysis of two studies, the Canada-USA (CANUSA) Peritoneal Dialysis Study9 and the ADEquacy of PD in MEXico (ADEMEX) trial,10 highlighted the benefit associated with RKF. Consequently, RKF has been referred to as the “heart” of peritoneal dialysis.11 However, due to the ease of achieving an “adequate” urea clearance by hemodialysis, RKF had long been ignored in patients treated with this modality. Emerging data in the past decade has changed this paradigm. The Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) Study reported that incident hemodialysis patients with preserved RKF at year 1 after dialysis initiation had a 30% lower risk of all-cause mortality and a 31% lower risk of cardiovascular death.12 Similar findings were reported by The Netherlands Cooperative Study on Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD)13 and more recently by a retrospective cohort study of patients treated at a large dialysis organization in the US.14,15 The association of higher RKF with improved outcomes in both peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis is likely a manifestation of higher solute and fluid excretion in patients with RKF, compared to those without RKF.

Together, these data suggest that presence of RKF in patients on dialysis is an important characteristic that should be factored into dialysis care. However, although more than one million people started dialysis in the past decade, no clinical trials have addressed the question of dialysis dosing accounting for RKF.16 The National Cooperative Dialysis Study (NCDS) and the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Trial, both excluded patients with RKF. More recently, increasing focus on the benefits of RKF and the factors associated with of loss of RKF, has revived the concept of incremental dialysis where dialysis is prescribed to supplement RKF to reach a prescribed total small solute clearance.17–21 Key to these proposals is the ability to reliably assess RKF.

Methodological Issues in Assessing RKF

RKF is generally assessed by methods used to assess GFR. In principle, GFR is product of the average filtration rate of each nephron times the number of nephrons. “True GFR” cannot be measured directly in humans. Instead, GFR is assessed from clearance measurements or estimated from plasma levels of filtration markers. Both measured GFR (mGFR) and estimated GFR (eGFR) may differ from true GFR due to systematic error (bias) or random error (imprecision); quantifying bias and imprecision is important in comparing GFR measurement and estimation methods. Several aspects of GFR assessment methods have implications for GFR measurement and estimation in dialysis patients.

First, due to the intermittent nature of dialysis there are hemodynamic perturbations that can affect true GFR. For example, volume overload before dialysis and volume removal during intermittent hemodialysis cause variation in true GFR, with lowest levels immediately post-dialysis and highest levels pre-dialysis.22

Second, solute clearance by dialysis is not the same as by the kidney. The diffusion coefficients for dialysis membranes and sieving coefficients of the glomerulus are each inversely related to the molecular size of the solute, but the apparent “cut off” size is higher for the glomerulus than for dialysis membrane. Small solutes [<500 Da, such as urea (60 Da) or creatinine (113 Da)] are freely filtered by the glomerulus and diffuse through dialysis membranes. Substantial amounts of “middle” molecular weight solutes (500 to 30,000 Da) are filtered, but are variably removed by dialysis (Table 1). For example, only small amounts of cystatin C (13,300 Da) and β2-microglobulin (B2M; 11,600 Da) are removed by low-flux hemodialysis, but larger amounts are removed by peritoneal dialysis and high-flux hemodialysis, whereas only minimal amounts of β-trace protein (BTP; 23,000 to 25,000 Da) is removed by any form of dialysis.23 For protein-bound solutes (such as p-cresol sulfate; 187 Da), the protein-bound fraction is not filtered and only the very small amounts of free (non-bound) solute is available for diffusion across the dialysis membrane. Protein-bound solutes may be efficiently removed by tubular secretion, but not by glomerular filtration or any form of dialysis. For sequestered solutes (such as oxalate; 128 Da or phosphate; 95 Da), the solute may be efficiently cleared from plasma during dialysis but rebound from other compartments to plasma may rapidly increase the plasma concentrations after dialysis is stopped.24 Sequestered solutes are more efficiently removed by glomerular filtration or continuous dialysis than intermittent dialysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of filtration markers used for measurement and estimation of residual kidney function

| Filtration Marker, Molecular Weight | Characteristics, Assay | Sources | Renal Tubular Handling | Extra-Renal Elimination – Endogenous ml/min/1.73 m2 | Extra-Renal Elimination – HD | Extra-Renal Elimination – PD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Exogenous | ||||||

| Inulin | Fructose polymer Protein binding: 10%57 | IV infusion or bolus | None | −7 to 9 58 | Yes43 | Yes43 |

| 5,200 Da | HPLC, LC-MS/MS | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Iothalamate | 125Iodine or unlabeled (“cold”) | IV infusion or bolus Subcutaneous bolus | Secretion59,60 | 4 to 10 37 | Yes61 | Yes62 |

| 636 Da | HPLC, LC-MS/MS | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 99mTc-DTPA | Protein binding: 11%57 | IV bolus | Not described | ~8 63 | Yes 64 | Yes 64 |

| 487 Da | Gamma camera/SPECT | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 51Cr-EDTA | Protein binding: 12%57 | IV infusion or bolus | Unclear | 2 to 4 37 | Likely | Yes65,66 |

| 339 Da | SPECT | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Iohexol | Contrast agent | IV bolus or infusion | Possible reabsorption68 | 0 to 6 35–37 | Yes69–71 | Yes71 |

| 821 Da | HPLC, LC-MS/MS Standardization67 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Endogenous | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Urea | Direct measurement, enzymatic colorimetric, | Protein intake, protein catabolism | Reabsorbed | No38 | Yes | Yes |

| 60 Da | electrochemical, others | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Creatinine | Colorimetric or enzymatic | Muscle, cooked meat72 | Secreted | Gastrointestinal39 | Yes | Yes |

| 133 Da | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cystatin C | Immunonephelometric Immunoturbidimetric | Nucleated cells | Reabsorbed, catabolized b | Yes48,49 | Low flux: None | Variablea |

| 13,300 Da | Others | High flux: 73±9%23 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| β-2 microglobulin | Immunonephelometric | Nucleated cells | Reabsorbed, catabolized b | Likely | Low flux: None | Variablea |

| 11,600 Da | High flux: 62±8%23 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| β-trace protein | Immunonephelometric ELISA | Leptomeninges, choroid plexus, other | Reabsorbed, catabolized b | Likely | Low flux: None | Not known |

| 23,000 to 29,000 Da | High flux: 26±19%23 | |||||

Abbreviations: HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; ELISA, Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; SPECT, Single photon emission computerized tomography; HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; IV, intravenous; 51 Cr-EDTA, 51Cr-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

In normal subjects, about one quarter of the urea produced in the liver is hydrolyzed by bacterial urease in the gastrointestinal tract to ammonia and carbon dioxide, which is converted back to urea in the liver.38

Third, GFR is typically reported in units of ml/min and indexed to body surface area (BSA), as a proxy for kidney size.25 BSA is calculated from height and weight and GFR is expressed per 1.73 m2 which was the mean BSA for men and women when GFR indexing was initially proposed. Average body size today is larger than 1.73 m2, and larger body size may affect measured and estimated GFR differently. Like GFR, tubular secretion can be expressed as clearance and indexed by BSA. In contrast, dialysis clearance is expressed as Kt/V for urea, where K is urea clearance in ml/min per dialysis session, t is time in minutes per dialysis session, and V is the volume of distribution of urea in ml, which is estimated from total body water (TBW). TBW is calculated from age, sex, and height. Kt/Vurea is usually expressed as clearance per hemodialysis treatment in the form of single pool Kt/Vurea (spKt/Vurea). Other formulations of Kt/Vurea include the weekly standard Kt/Vurea (stdKt/Vurea) which is considered a “continuous equivalent” urea clearance that allows comparison of total urea clearance (RKF and dialysis) across different hemodialysis frequencies and between intermittent hemodialysis and continuous peritoneal dialysis.26 A recent post-hoc analyses of the HEMO trial questioned whether it would be more appropriate to index dialysis clearance by measures of body size other than TBW, such as the BSA.27 Combining GFR, clearance due to tubular secretion and dialysis clearance into a single measure of total clearance will require standardizing the measures.

RKF Measurement

GFR can be measured as clearance of an exogenously administered marker, such as inulin, or an endogenous marker, such as urea or creatinine. Clearance of exogenous markers can be measured as plasma or urinary clearance; clearance of an endogenous marker requires urinary clearance measurement. The plasma clearance of a marker represents the net effect of renal and extra-renal clearance. Urinary clearance represents renal clearance, which is the net effect of glomerular filtration, tubular secretion, and reabsorption. Therefore, for markers with significant extra-renal elimination, the plasma clearance exceeds urinary clearance. Similarly, for markers with significant tubular secretion, the urinary clearance is higher than the GFR, and for substances with significant tubular reabsorption, the urinary clearance is lower than the GFR. At low GFR, these differences are small when expressed on the absolute scale but large when expressed on the relative scale. For a marker whose mechanism of excretion is unknown, the mechanisms may be inferred by comparing plasma and urinary clearances with markers whose mechanisms of excretion are known.

In general, the clearance of a marker x (CLx, expressed in ml/min) is computed by the amount of the marker removed from the plasma during a given time (Ax) divided by the average plasma concentration of the marker (Px) during that time.28 Urinary clearance of the marker is computed by the amount of the marker excreted in the urine during a given time (UxV) divided by (Px) during the urine collection. Measurement of urinary clearance has the inherent limitations associated with urine collection, including errors in collection and incomplete bladder emptying. Due to these difficulties, plasma clearance of an exogenously administered marker presents an attractive option to measure GFR. In this technique, the amount (dose) of the administered marker is known and multiple time point blood sampling can allow calculation of Px as the area under the marker disappearance curve extrapolated to complete elimination of the marker.

There are many challenges to performing clearance measurements in dialysis patients. 1) Urinary clearance measurements may be inaccurate due to low urine flow rates, which can magnify errors due to incomplete bladder emptying and incomplete collections. 2) Plasma clearance measurements can be inaccurate due to extracellular fluid excess, which increases the volume of distribution of exogenous filtration markers. 3) Endogenous extra-renal elimination, although low, may be large in proportion to renal clearance. 4) Clearance measurements must be performed between dialysis procedures to avoid extra-renal elimination of the marker by dialysis. 5) Low renal clearance results in a slow decay in plasma concentrations of exogenous markers, requiring long-sampling times for plasma clearance, often exceeding 24 hours. 6) Repeated blood sampling for plasma clearance can be challenging in patients with poor vascular access.

RKF Estimation

GFR estimation from serum levels of endogenous filtration markers, creatinine and cystatin C, are now recommended by practice guidelines for routine clinical use. However, plasma concentrations of these and all endogenous filtration markers are dependent on factors other than GFR (“non-GFR determinants”), including generation, tubular secretion and reabsorption and extra-renal elimination. Equations to estimate GFR from plasma concentrations of filtration markers model the filtration marker as a function of the mGFR, and include demographic and clinical variables, such as age, sex, and race, to serve as surrogates for non-GFR determinants of the marker.29 Variation from the average value for the association between the surrogates and the non-GFR determinants leads to differences between eGFR and mGFR (error in eGFR).28 Additional sources of error in GFR estimates include measurement error in the assay of the endogenous filtration marker or in mGFR compared to true GFR.

For the reasons below, GFR estimating equations that were not developed in patients on dialysis are not expected to be accurate in dialysis patients. 1) As in non-dialysis patients, markers are generated by metabolic processes in cells or from dietary intake, but associated clinical conditions, altered dietary patterns and microbiome in dialysis patients may result in substantial differences in generation rates compared to non-dialysis patients. 2) As in non-dialysis patients, excretion of the marker by the kidney is predominantly by glomerular filtration, but tubular secretion and reabsorption may contribute proportionately more in dialysis patients. 3) In addition to extra-renal elimination by organs, removal by the dialyzer may cause wide variation in plasma levels, especially if removal is efficient. Different dialysis modalities (peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis) and regimens (intermittent, frequent, and continuous) differ in their efficiency in clearing different solutes. All of these limitations may be overcome by developing estimating equations in dialysis patients, however, the difficulty in measuring GFR in dialysis patients may limit the performance of estimating equations.

Performance metrics for GFR estimating equations include bias, precision, and accuracy.30 Bias is the mean or median difference between the reference (gold standard) test and the index test (estimating equation). Precision is the variability in the differences which can be expressed as the standard deviation or the interquartile difference. Accuracy is typically reported as the proportion of estimates that fall within a certain range of the reference test, for example 30% (P30). The interpretation of the accuracy metric depends on the level of GFR. For example, a 5 ml/min/1.73 m2 difference may be unimportant if mGFR is 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, but is obviously important if mGFR is only 5 ml/min/1.73 m2. Therefore, for dialysis patients, an alternative metric of accuracy, such as the proportion of estimates within 2 ml/min/1.73 m2, has been proposed and used for assessing accuracy.31–34

Filtration Markers for RKF Measurement and Estimation

Exogenous filtration markers

Exogenous filtration markers that have been used for GFR measurement in dialysis patients are described in Table 1. Because of their low molecular weight, all are cleared by all dialysis modalities, requiring GFR measurement between dialysis treatments. Protein binding is generally low. Iothalamate is secreted. Most importantly, all markers, including inulin, have extra-renal elimination, which is often highly variable. For example, extra-renal clearance of iohexol can vary between 0–6 ml/min/1.73 m2 (Figure 1).35–37 This high degree of variability at a very low GFR (mean ~5 ml/min/1.73 m2) precludes using a “correction factor” for extra-renal clearance. Reliable GFR measurement using plasma clearance of an exogenous filtration marker may not be a feasible strategy for RKF assessment.

Endogenous filtration markers

Metabolites and plasma proteins have been used as endogenous filtration markers for GFR estimation in dialysis patients; characteristics are described in Table 1.

Urea and creatinine are metabolites that are freely filtered and excreted in the urine, but urea is reabsorbed and creatinine is secreted by the renal tubule. Urea is generated by digestion of dietary protein and catabolism of endogenous protein, and varies with diet, medications, and acute and chronic illness.38 Creatinine is generated by muscle creatine breakdown and meat intake, and varies with muscle mass and diet.39 Creatinine undergoes extra-renal elimination by the gastrointestinal tract.

Studies in patients not on dialysis with GFR <20 ml/min/1.73 m2 (measured using inulin clearance) show that the magnitude of clearance due to urea reabsorption is similar to the magnitude of clearance due to creatinine secretion,40,41 leading to the widely-used practice of estimating GFR from the average of urea and creatinine clearance. Reanalysis of data from a study of dialysis patients reported by Milutinovic et al. demonstrates similarity of urinary inulin clearance with the average of urinary urea and creatinine clearance; mean difference of 0.007 ml/min (25th to 75th percentiles, –0.02 to 0.04).42 Based on these findings, in routine clinical practice and in research studies, RKF is generally measured using urinary clearance of urea and creatinine. Limitations of this method are numerous, including the errors and reliability of urine collection, timing of blood sampling for measurement of urea and creatinine, and the duration of collection. Since neither urea nor creatinine are in steady state in the interdialytic interval, accurate calculation requires blood samples from multiple time points during the urinary collection interval. At minimum 2 samples are required – first blood sample when the urine collection is initiated and second sample at the end of collection, usually at the start of dialysis session or another “routine” blood draw. The need to minimize blood draws has resulted in the routine clinical practice of interdialytic urine collection over a period of two days in hemodialysis patients. The onerous nature of this collection and the potential for errors greatly limits its utility and feasibility. In patients treated with peritoneal dialysis, a 24-hour urine collection is often performed at the time of quarterly assessment of peritoneal dialysis clearance, with a single blood sample at the end of collection, assuming urea and creatinine are in the steady state. However, in patients treated with intermittent peritoneal dialysis using a cycler, this assumption is not valid; urea and creatinine are lowest at the end of the cycler treatment.

An additional consideration, particularly in patients treated with intermittent hemodialysis, is the variability in GFR during the interdialytic interval. A study by van Olden et al., examined this question and found that the GFR measured using urinary inulin clearance did not vary in the interdialytic interval for patients treated with peritoneal dialysis43,44 but for hemodialysis patients, it was lowest immediately after hemodialysis and highest preceding the next hemodialysis session.22 The authors concluded that the optimal method for measuring GFR by urinary urea and creatinine clearance is by a 12-hour urine collection immediately preceding the dialysis session and a single blood sample obtained at the end of the 12-hour interval.22 This approach, based on rigorous scientific data, may be the most optimal way of measuring GFR by urinary clearance of urea and creatinine.

Plasma proteins, including cystatin C, β-2 microglobulin, and β-trace protein have certain common features as filtration makers. All are filtered freely by the glomerulus and then reabsorbed and completely metabolized by the renal tubular cells. Therefore, the plasma concentrations are largely determined by rates of generation and glomerular filtration. Cystatin C is a 13,300 Da protein produced by all nucleated cells in the body.45 The plasma concentration is influenced by many factors thought to reflect variation in generation,46,47 including smoking, adiposity, thyroid disease, and inflammation, the latter a common problem in dialysis patients. There is some evidence suggesting extra-renal elimination.48,49 Cystatin C is removed by both peritoneal dialysis50 and high-flux, but not low-flux, hemodialyzers.23 As a result, cystatin C is not in a steady state in the interdialytic interval; in a controlled research setting, mean interdialytic rise of cystatin C is 0.3 mg/L per day (p=0.005).32 An international standard for cystatin C is now available,51–53 but standardization of assays is not complete.

β-2 microglobulin is a 11,600 Da protein which is the component of the major histocompatibility molecules that are present on nucleated cells.54 Its plasma concentration is influenced by malignancy and inflammation.46,47 Like cystatin C, β-2 microglobulin is removed by high-flux hemodialysis and by peritoneal dialysis. In the interdialytic interval β-2 microglobulin is not in a steady state, with a mean interdialytic rise of 1.27 mg/L per day.32 There are several assays which are not standardized.

β-trace protein is a 23,000–29,000 Da glycoprotein which is produced by the leptomeninges, arachnoid cells, choroid plexus, and oligodendrocytes of the central nervous system.55 Other sources of β-trace protein include cochlear cells, testicular Sertoli and Leydig cells, vascular endothelial cell, and adipocytes. Extra-renal elimination is likely but has not yet been characterized. β-trace protein is removed to a much smaller extent by high-flux hemodialysis compared to cystatin C and β-2 microglobulin23 and as a result its plasma levels appear to be in steady state in the interdialytic interval (mean interdialytic rise 0.09 mg/L per day; p=0.71)32 in patients treated with hemodialysis using high-flux membranes. Super high-flux membranes, which can remove proteins up to 65,000 Da, and hemodiafiltration can remove β-trace protein as effectively as cystatin C and β-2 microglobulin.23 Removal of β-trace protein by peritoneal dialysis has not yet been described. There are two commercially available assays for β-trace protein. Most studies that developed estimating equations using β-trace protein used the Siemens nephelometric immunoassay. An ELISA assay for BTP by Cayman Chemicals is also available. There appears to be considerable variability between the assays.56

Studies of RKF Measurement Techniques

Table 2 describes the characteristics of 10 studies with GFR measurement using exogenous filtration markers. Due to the low GFR, most studies used long sampling times to assess plasma clearance, but the urinary clearance protocols were variable. All studies included measurement of plasma and urinary clearance, enabling conclusions about extra-renal elimination. Only 1 study included inulin plus other alternative markers, enabling conclusions about renal tubular handling of the alternative markers.42

Table 2.

Residual kidney function measurement using exogenous filtration markers

| Urinary and Plasma Clearance Measurement Technique | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, Year | N, Modality | Filtration Marker Administration and Dosea | Urine Collection Location | Blood Sampling Timing |

| Milutinovic et al.42 1975 | 38, HD | Inulin IV bolus, 50 mg/kg 125Iothalamate IV bolus, 0.3 μCi/kg 169Yb-DTPA IV bolus, 0.3 μCi/kg |

Supervised collection Location not described |

T0, T1 hr, T12 hr, T24 hr |

| Teplan et al.73 1984 | 20, HD | Inulin – details not provided | Location not described | Single sample at mid-point of urine collection |

| van Olden et al.22 1995 | 11, HD | Inulin 10 g IV bolusb | 4 interdialytic collection intervals Location not described |

At the beginning and end of each interval |

| van Olden et al.43,44 1996 | 10, PD | Inulin 2.5 g IV bolus | Location not described | Timing not described |

| Swan et al.74 1996 | 33, HD | Iohexol IV bolus, 12 ml | Home | Post HD at 24 and 44 hours |

| Sacamay et al.75 1998 | 10, HD | Iohexol IV bolus, 30 ml | Home | Pre, intra, post HD |

| Sterner et al.76 2000 | 12, HD | Iohexol IV bolus, 15 ml Iodixanol IV bolus, 15 ml |

Home | T1 5–12 hrs; T2 44–48 hrs |

| Kjaergaard et al.65,66 2011, 2013 | 24 (HD: 12 PD: 12) | 51Cr-EDTA IV bolus, 3.7 MBq | Home | T3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 24 hrs |

| Carter et al.,77 2011 | 28, PD | 51Cr-EDTA IV bolus, 3.0 MBq | Home | T3, 6, 7 hrs |

| Shafi et al.35 2016 | 40 (HD: 36 PD: 4) | Iohexol IV bolus, 5 ml | Interdialytic day Supervised inpatient |

10 min, 30 min, 2 hrs, 4 hrs, 24 hrs |

Abbreviations: T, Time; HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; IV, intravenous; 51 Cr-EDTA, 51Cr-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; min, minutes; hrs, hours

Contrast media (iohexol and iodixanol) had different iodine content in different studies

Administered 2 hour before the end of dialysis

Studies of RKF Estimating Equations

The optimal design for a study to develop RKF estimating equations from serum filtration markers has several important components. First, the mGFR should be highly reliable, minimizing systematic errors. This would require that the measurement occur in a research setting with good quality control and reproducibility. Second, the studies should include patients treated with different dialysis modalities and schedules, with careful recording of the dialysis treatment schedule and standardization of the day of the week when measurements take place. Third, the analytic variability in endogenous filtration markers should be minimized by standardization of laboratory testing assays. Fourth, the equation development and validation cohorts should be separate; ideally the validation cohort should be completely external to the development cohort population. Finally, detailed evaluation of equation performance should be performed to allow comparability to prior and future studies.

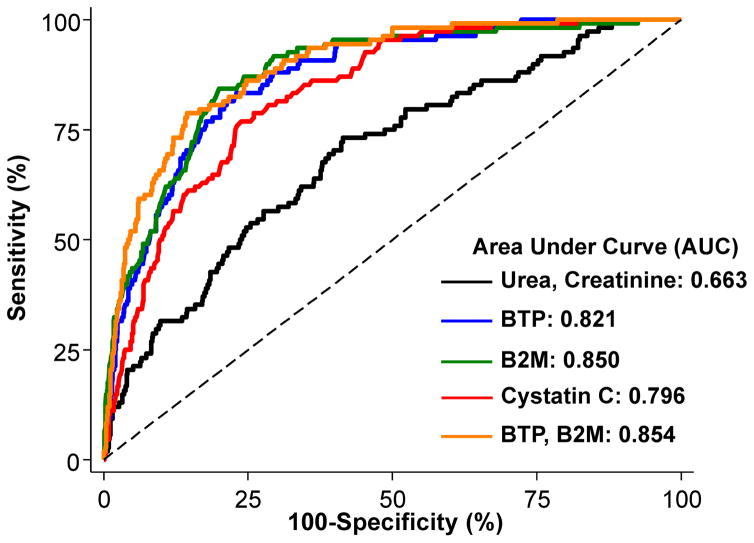

The RKF estimation equation literature is in relative infancy compared to studies of GFR estimation in non-dialysis patients. In most published studies, GFR measurement was performed by measurement of urinary clearance of urea and creatinine, collected as part of clinical care. Most studies only reported correlations with markers and only a few studies developed estimation equations. The studies that developed RKF estimation equations are presented in Table 3. External validation of the estimating equation was performed in only 1 study.32 The bias (measured GFR – estimated GFR) was generally low in most studies but this could simply be a function of the low range of GFR. The accuracy appeared to be better for equations using low molecular weight proteins as compared with metabolites (urea and creatinine). In general, there was low sensitivity but high specificity of the equations to accurately classify patients above or below a urea clearance threshold of 2 ml/min, an arbitrarily defined cut-off for hemodialysis dosing (Figure 2). In the only study with external validation, the root mean squared error of the relationship between measured and estimated GFR was relatively large suggesting presence of variability that was not completely captured by the variables in the estimating equations.32 These errors could result from errors in measured GFR, laboratory test analytic variability in assays for the endogenous filtration markers, or from variation in non-GFR determinants that was not captured by the coefficients in the estimating equation.

Table 3.

Residual kidney function estimation using serum concentrations of endogenous filtration markers

| Author, Year | Equation Development | Performance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation |

External Validation | ||||||

| Development, Internal Validation |

External Validation |

GFR Measurement Methoda |

Markers, Other variables |

Accuracy (AUC)b |

Bias (mGFR- eGFR)c |

Accuracy (AUC)2, 3 |

|

| Hoek et al.78 2007 | Development: N=310 (215 HD, 95 PD) Internal validation: 155 (107 HD, 48 PD) |

None | CLUREA,CREAT | Cystatin C | AUC not reported P30: 43% P50: 65% |

— | — |

| Yang et al.31 2011 | Development: 120 PD Internal Validation: 40 PD |

None | CLUREA,CREAT | Cystatin C | 0.74 | — | — |

| Creatinine | 0.78 | — | — | ||||

| Shafi et al.35 2016 | N=44 (40 HD; 4 PD) | N=826 (587 HD; 239 PD) | CLUREA, CREAT | Urea, Creatinine | 0.66 | 0.3 | 0.73 |

| BTP, sex | 0.68 | 0.6 | 0.85 | ||||

| B2M, sex | 0.77 | 1.0 | 0.88 | ||||

| Cystatin C | 0.73 | 0.7 | 0.84 | ||||

| BTP, B2M, sex | 0.77 | 0.7 | 0.89 | ||||

| Wong et al.33 2016 | Development: N=191 HD Internal validation=40 HD |

None | CLUREA, CREAT | BTP, B2M, creatinine, Sex | 0.91 | — | — |

| Vilar et al.34 2016 | Development: N=341 HD Internal validation: N=50 HD |

None | CLUREA | B2M | 0.91 | — | — |

| Cystatin C | 0.86 | — | — | ||||

| Creatinine | 0.74 | — | — | ||||

| Urea | 0.86 | — | — | ||||

Abbreviations: GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; CL, clearance; CLUREA urinary urea clearance; CLUREA, CREAT, average of urinary urea and creatinine clearance; AUC, area under the receiver operator curve; P30, percent of estimates within 30% of CLUREA, CREAT; P50, percent of estimates within 50% of CLUREA, CREAT

All GFR measurements are urinary clearances. Performance data for only CLUREA, CREAT is reported in the Table for the studies that reported equations for both CLUREA and CLUREA, CREAT.

AUC for correctly identifying measured GFR of 2 ml/min or 2 ml/min/1.73 m2 (depending on the study).

Data not available for studies that did not perform external validation.

Figure 2. Extra-Renal Clearance of Iohexol.

Comparison of clearance measurements in the Residual Kidney Function Study.35,36 (A) Scatterplot of 24-hour plasma clearance of iohexol (CL iohexol ) versus 24-hour urinary CL iohexol . Dashed lines and shaded areas represent the linear fit and confidence interval of the linear regression. (B) Plot of extrarenal CL iohexol (24-hour plasma CL iohexol- 24-hour urinary CL iohexol ) versus 24-hour urinary CL iohexol . Positive numbers represent overestimation of 24-hour urinary CL iohexol ; negative numbers, underestimation. Dashed line represents fit from a median quantile regression of the extrarenal CL iohexol on 24-hour urinary CL iohexol . Abbreviation: RMSE, root-mean-square error. From Shafi et al, reproduced with permission.36

Future Directions

Assessment of kidney function by eGFR is the cornerstone of management in patients with CKD not treated by dialysis. RKF after dialysis initiation is strongly associated with survival, likely due to its effects on fluid and solute excretion. There is mounting support for individualizing the care of dialysis patients with RKF by prescribing incremental dialysis regimens, tailored to the patient’s needs. Reliable assessment of RKF without urine collection is the biggest hurdle in achieving prescribed total small solute clearance. Improving RKF estimation can overcome this hurdle but will require efforts to improve GFR measurement techniques and identification of new endogenous filtration markers to improve the reliability of GFR estimation.

Figure 3. Diagnostic Accuracy for Estimating CLUREA ≥2 ml/min.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the diagnostic accuracy of estimating equations by Shafi et al.32 in 826 dialysis patients of the NECOSAD. Sensitivity (%) is presented on the y-axis and 100-Specificity (%) is presented on the x-axis. Solid black line was calculated using the urea and creatinine equation, solid blue line the BTP equation, solid green line the B2M equation, solid red line the cystatin C equation, and orange line the BTP + B2M equation. B2M, β2 microglobulin; BTP, β-trace protein; CLUREA, urinary urea clearance (ml/min); CLUREA, CREAT, average of urinary urea and creatinine clearance (ml/min/1.73 m2); NECOSAD, Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis. From Shafi et al.,32 modified with permission.

Clinical Summary.

Residual kidney function is the kidney function in patients treated with dialysis; “total kidney function” is the sum of residual kidney function plus function provided by kidney replacement therapy.

“Total small solute clearance” in dialysis patients is a component of total kidney function and is the sum of small solute clearance by glomerular filtration, tubular secretion and the dialysis modality.

Assessment of residual kidney function requires measurement or estimation of glomerular filtration rate from clearance or serum concentrations of filtration markers.

Estimation of glomerular filtration rate by serum concentrations of low molecular weight proteins is a promising new method to assess residual kidney function without urine collection.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Shafi reports grant support from NIDDK and Siemens for studies on residual kidney function and honorarium from Siemens for invited lectures.

Dr. Shafi was supported by R03-DK-104012 and R01-HL-132372-01. .

Dr. Levey reports grant support from Dialysis Clinic, Inc. and Siemens for studies on residual kidney function.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sirich TL, Meyer TW, Gondouin B, Brunet P, Niwa T. Protein-bound molecules: a large family with a bad character. Semin Nephrol. 2014 Mar;34(2):106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowenstein J, Grantham JJ. Residual renal function: a paradigm shift. Kidney Int. 2017 Mar;91(3):561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer TW, Sirich TL, Fong KD, et al. Kt/Vurea and Nonurea Small Solute Levels in the Hemodialysis Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Nov;27(11):3469–3478. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015091035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirich TL, Funk BA, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW. Prominent accumulation in hemodialysis patients of solutes normally cleared by tubular secretion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Mar;25(3):615–622. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013060597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Renal Data System. 2016 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2016. [Accessed June 29, 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. CDC Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Atlanta, GA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merkus MP, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, de Haan RJ, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. Physical symptoms and quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis: results of The Netherlands Cooperative Study on Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999 May;14(5):1163–1170. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.5.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ. The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007 Jan;14(1):82–99. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bargman JM, Thorpe KE, Churchill DN. Relative contribution of residual renal function and peritoneal clearance to adequacy of dialysis: a reanalysis of the CANUSA study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001 Oct;12(10):2158–2162. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paniagua R, Amato D, Vonesh E, et al. Effects of increased peritoneal clearances on mortality rates in peritoneal dialysis: ADEMEX, a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 May;13(5):1307–1320. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1351307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang AY. The "heart" of peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2007 Jun;27( Suppl 2):S228–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shafi T, Jaar BG, Plantinga LC, et al. Association of residual urine output with mortality, quality of life, and inflammation in incident hemodialysis patients: the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010 Aug;56(2):348–358. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Termorshuizen F, Dekker FW, van Manen JG, Korevaar JC, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. Relative contribution of residual renal function and different measures of adequacy to survival in hemodialysis patients: an analysis of the Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD)-2. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004 Apr;15(4):1061–1070. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000117976.29592.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obi Y, Rhee CM, Mathew AT, et al. Residual Kidney Function Decline and Mortality inIncident Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Dec;27(12):3758–3768. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015101142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obi Y, Streja E, Rhee CM, et al. Incremental Hemodialysis, Residual Kidney Function, and Mortality Risk in Incident Dialysis Patients: A Cohort Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016 Aug;68(2):256–265. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafi T, Mullangi S, Toth-Manikowski SM, Hwang S, Michels WM. Residual KidneyFunction: Implications in the Era of Personalized Medicine. Semin Dial. 2017 May;30(3):241–245. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghahremani-Ghajar M, Rojas-Bautista V, Lau WL, et al. Incremental Hemodialysis: TheUniversity of California Irvine Experience. Semin Dial. 2017 May;30(3):262–269. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew A, Obi Y, Rhee CM, et al. Treatment frequency and mortality among incident hemodialysis patients in the United States comparing incremental with standard and more frequent dialysis. Kidney Int. 2016 Nov;90(5):1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golper TA. Incremental Hemodialysis: How I Do It. Semin Dial. 2016 Nov;29(6):476–480. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bargman JM, Jones CB. The Interaction of Dialysis Prescription and Residual KidneyFunction: Yet Another Layer of Complexity. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 Apr;69(4):489–491. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toth-Manikowski SM, Shafi T. Hemodialysis Prescription for Incident Patients: TwiceSeems Nice, But Is It Incremental? Am J Kidney Dis. 2016 Aug;68(2):180–183. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Olden RW, van Acker BA, Koomen GC, Krediet RT, Arisz L. Time course of inulin and creatinine clearance in the interval between two haemodialysis treatments. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995 Dec;10(12):2274–2280. doi: 10.1093/ndt/10.12.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donadio C, Tognotti D, Caponi L, Paolicchi A. beta-trace protein is highly removed during haemodialysis with high-flux and super high-flux membranes. BMC Nephrol. 2017 Feb 20;18(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0489-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eloot S, Torremans A, De Smet R, et al. Complex compartmental behavior of small water-soluble uremic retention solutes: evaluation by direct measurements in plasma and erythrocytes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007 Aug;50(2):279–288. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levey AS, Kramer H. Obesity, glomerular hyperfiltration, and the surface area correction. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010 Aug;56(2):255–258. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Hemodialysis Adequacy: 2015 Update. Am JKidney Dis. 2015 Nov;66(5):884–930. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daugirdas JT, Greene T, Chertow GM, Depner TA. Can rescaling dose of dialysis to body surface area in the HEMO study explain the different responses to dose in women versus men? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Sep;5(9):1628–1636. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02350310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey AS, Inker LA, Coresh J. GFR estimation: from physiology to public health. Am JKidney Dis. 2014 May;63(5):820–834. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009 May 5;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens LA, Zhang Y, Schmid CH. Evaluating the performance of equations for estimating glomerular filtration rate. J Nephrol. 2008 Nov-Dec;21(6):797–807. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Q, Li R, Zhong Z, et al. Is cystatin C a better marker than creatinine for evaluating residual renal function in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011 Oct;26(10):3358–3365. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shafi T, Michels WM, Levey AS, et al. Estimating residual kidney function in dialysis patients without urine collection. Kidney Int. 2016 May;89(5):1099–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong J, Sridharan S, Berdeprado J, et al. Predicting residual kidney function in hemodialysis patients using serum beta-trace protein and beta2-microglobulin. Kidney Int. 2016 May;89(5):1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2015.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vilar E, Boltiador C, Wong J, et al. Plasma Levels of Middle Molecules to EstimateResidual Kidney Function in Haemodialysis without Urine Collection. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shafi T, Levey AS, Inker LA, et al. Plasma Iohexol Clearance for Assessing ResidualKidney Function in Dialysis Patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015 Oct;66(4):728–730. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shafi T, Levey AS, Coresh J. Reply to 'Plasma Clearance of Iohexol in HemodialysisPatients Requires Prolonged Blood Sampling'. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016 May;67(5):811–812. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delanaye P, Ebert N, Melsom T, et al. Iohexol plasma clearance for measuring glomerular filtration rate in clinical practice and research: a review. Part 1: How tomeasure glomerular filtration rate with iohexol? Clinical Kidney Journal. 2016;9(5):682–699. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfw070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walser M. Determinants of ureagenesis, with particular reference to renal failure. Kidney international. 1980 Jun 01;17(6):709–721. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levey AS. Measurement of renal function in chronic renal disease. Kidney Int. 1990 Jul;38(1):167–184. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lubowitz H, Slatopolsky E, Shankel S, Rieselbach RE, Bricker NS. Glomerular filtration rate. Determination in patients with chronic renal disease. JAMA. 1967 Jan 23;199(4):252–256. doi: 10.1001/jama.199.4.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavender S, Hilton PJ, Jones NF. The measurement of glomerular filtration-rate in renal disease. Lancet. 1969 Dec 06;2(7632):1216–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90752-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milutinovic J, Cutler RE, Hoover P, Meijsen B, Scribner BH. Measurement of residual glomerular filtration rate in the patient receiving repetitive hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 1975 Sep;8(3):185–190. doi: 10.1038/ki.1975.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Olden RW, Krediet RT, Struijk DG, Arisz L. Measurement of residual renal function in patients treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996 May;7(5):745–750. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V75745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Olden RW, Krediet RT, Struijk DG, Arisz L. Similarities in functional state of the kidney in patients treated with CAPD and hemodialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 1996;12:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seronie-Vivien S, Delanaye P, Pieroni L, et al. Cystatin C: current position and future prospects. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46(12):1664–1686. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu X, Foster MC, Tighiouart H, et al. Non-GFR Determinants of Low-Molecular-WeightSerum Protein Filtration Markers in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016 Dec;68(6):892–900. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foster MC, Levey AS, Inker LA, et al. Non-GFR Determinants of Low-Molecular-WeightSerum Protein Filtration Markers in the Elderly: AGES-Kidney and MESA-Kidney. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 May 24; doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tenstad O, Roald AB, Grubb A, Aukland K. Renal handling of radiolabelled human cystatin C in the rat. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1996;56(5):409–414. doi: 10.3109/00365519609088795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horio M, Imai E, Yasuda Y, Watanabe T, Matsuo S. Performance of serum cystatin C versus serum creatinine as a marker of glomerular filtration rate as measured by inulin renal clearance. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2011 Dec;15(6):868–876. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0525-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steubl D, Hettwer S, Dahinden P, et al. C-terminal agrin fragment (CAF) as a serum biomarker for residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015 Feb;47(2):391–396. doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0852-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grubb A, Horio M, Hansson LO, et al. Generation of a new cystatin C-based estimating equation for glomerular filtration rate by use of 7 assays standardized to the international calibrator. Clinical chemistry. 2014 Jul;60(7):974–986. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.220707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mueller L, Pruemper C. Performance in Measurement of Serum Cystatin C byLaboratories Participating in the College of American Pathologists 2014 CYS Survey. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016 Mar;140(3):207. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0353-LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bargnoux AS, Pieroni L, Cristol JP, et al. Multicenter Evaluation of Cystatin CMeasurement after Assay Standardization. Clinical chemistry. 2017 Apr;63(4):833–841. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.264325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Argyropoulos CP, Chen SS, Ng Y-H, et al. Rediscovering Beta-2 Microglobulin As aBiomarker across the Spectrum of Kidney Diseases. Frontiers in Medicine. 2017 Jun 15;4(73) doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White CA, Ghazan-Shahi S, Adams MA. beta-Trace Protein: A Marker of GFR and OtherBiological Pathways. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2015 Jan;65(1):131–146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White CA, Akbari A, Eckfeldt JH, et al. beta-Trace Protein Assays: A ComparisonBetween Nephelometric and ELISA Methodologies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 Jun;69(6):866–868. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.02.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rehling M, Nielsen LE, Marqversen J. Protein binding of 99Tcm-DTPA compared with other GFR tracers. Nucl Med Commun. 2001 Jun;22(6):617–623. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soveri I, Berg UB, Bjork J, et al. Measuring GFR: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014 Sep;64(3):411–424. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Odlind B, Hallgren R, Sohtell M, Lindstrom B. Is 125I iothalamate an ideal marker for glomerular filtration? Kidney Int. 1985 Jan;27(1):9–16. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zurth C. Mechanism of renal excretion of various X-ray contrast materials in rabbits. Invest Radiol. 1984 Mar-Apr;19(2):110–115. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Evans JR, Cutler RE, Forland SC. Pharmacokinetics of iothalamate in endstage renal disease. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988 Sep;28(9):826–830. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mishkin GJ, Lew SQ, Bosch JP. Assessment of PD treatment delivered by 125I-Iothalamate plasma disappearance. Clin Nephrol. 1998 Mar;49(3):173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Filler G, Yasin A, Medeiros M. Methods of assessing renal function. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014 Feb;29(2):183–192. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2426-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wainer E, Boner G, Lubin E, Rosenfeld JB. Clearance of Tc-99m DTPA in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: concise communication. J Nucl Med. 1981 Sep;22(9):768–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kjaergaard KD, Jensen JD, Jespersen B, Rehling M. Reliability of (5)(1)Cr-EDTA plasma and urinary clearance as a measure of residual renal function in dialysis patients. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2011 Dec;71(8):663–669. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2011.619565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kjaergaard KD, Rehling M, Jensen JD, Jespersen B. Reliability of endogenous markers for estimation of residual renal function in haemodialysis patients. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2013 May;33(3):224–232. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Delanaye P, Ebert N, Melsom T, et al. Iohexol plasma clearance for measuring glomerular filtration rate in clinical practice and research: a review. Part 1: How to measure glomerular filtration rate with iohexol? Clin Kidney J. 2016 Oct;9(5):682–699. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfw070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seegmiller JC, Burns BE, Schinstock CA, Lieske JC, Larson TS. Discordance BetweenIothalamate and Iohexol Urinary Clearances. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016 Jan;67(1):49–55. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deray G. Dialysis and iodinated contrast media. Kidney international. 69:S25–S29. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Furukawa T, Ueda J, Takahashi S, Sakaguchi K. Elimination of low-osmolality contrast media by hemodialysis. Acta Radiol. 1996 Nov;37(6):966–971. doi: 10.1177/02841851960373P2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moon SS, Back SE, Kurkus J, Nilsson-Ehle P. Hemodialysis for elimination of the nonionic contrast medium iohexol after angiography in patients with impaired renal function. Nephron. 1995;70(4):430–437. doi: 10.1159/000188641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jacobsen FK, Christensen CK, Mogensen CE, Andreasen F, Heilskov NS. Pronounced increase in serum creatinine concentration after eating cooked meat. Br Med J. 1979 Apr 21;1(6170):1049–1050. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6170.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Teplan V, Schuck O, Nadvornikova H. Differences in the effect of hemodialysis on the residual clearance of inulin, endogenous creatinine, and urea. Artif Organs. 1984 Nov;8(4):488–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1984.tb04326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swan SK, Halstenson CE, Kasiske BL, Collins AJ. Determination of residual renal function with iohexol clearance in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1996 Jan;49(1):232–235. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sacamay TE, Bolton WK. Use of iohexol to quantify hemodialysis delivered and residual renal function: technical note. Kidney Int. 1998 Sep;54(3):986–991. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sterner G, Frennby B, Mansson S, Ohlsson A, Prutz KG, Almen T. Assessing residual renal function and efficiency of hemodialysis--an application for urographic contrast media. Nephron. 2000 Aug;85(4):324–333. doi: 10.1159/000045682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carter JL, Lane CE, Fan SL, Lamb EJ. Estimation of residual glomerular filtration rate in peritoneal dialysis patients using cystatin C: comparison with 51Cr-EDTA clearance. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011 Nov;26(11):3729–3732. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoek FJ, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. Estimation of residual glomerular filtration rate in dialysis patients from the plasma cystatin C level. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007 Jun;22(6):1633–1638. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]