Abstract

Objective

Few guidelines are available regarding optimal training models for practitioners delivering CBT for anxiety in youth with ASD. The present study systematically compared 3 instructional conditions for delivering the Facing Your Fears program (FYF) to children with ASD and anxiety.

Method

Thirty-four clinicians (Mage=34; 94% female, 88% Caucasian) and an intent-to-treat sample of 91 children with ASD and anxiety (Mage =11; 84% male; 53% Caucasian) met eligibility criteria across 4 sites. A three group parallel design via a Latin square procedure was used to randomize 9 teams of clinicians to one of three training conditions: Manual, Workshop, Workshop-Plus. The effectiveness of instructional condition was assessed via implementation (CBT knowledge, treatment fidelity) and treatment outcomes (reductions in anxiety as measured by the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Parent (ADIS-P).

Results

Clinicians in both Workshop conditions significantly increased CBT knowledge post-workshop, F(1,18)=19.8, p< .001. Excellent treatment fidelity was obtained across conditions (above 89%), although clinicians in the Workshop conditions obtained significantly higher fidelity ratings and delivered FYF with greater quality than the Manual condition. Children with ASD demonstrated significant reductions in anxiety symptoms for three of the four anxiety diagnoses, with no differences noted across instructional condition. Rates of improvement were lower than those obtained in a previous controlled trial.

Conclusions

Results suggest that although there may be some advantage to participating in a Workshop, clinicians in all conditions could deliver FYF with excellent fidelity and yield positive treatment outcomes. Lack of a no-treatment comparison group limits interpretation of findings.

Over the last decade, a steadily growing literature has documented that youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are at high risk for developing co-occurring psychiatric conditions, and anxiety disorders are among the most common co-morbid conditions (Simonoff et al., 2008; van Steensel, Bogels & Perrin, 2011). Anxiety interferes with functioning across contexts and is associated with a variety of negative outcomes (e.g., unemployment, substance abuse, additional psychiatric conditions, and increased financial burden; Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, Mauro & Compton, 2006; van Steensel, Dirksen, & Bogels, 2013). In spite of this clear health care need, access to quality mental health care is significantly limited for youth with ASD (Wainer et al. 2017).

Fortunately, psychosocial interventions based on the principles of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) have been developed to target the anxious symptoms experienced by youth with ASD in response to this significant mental health challenge (Wood et al. 2009; White et al. 2013). To date, approximately 14 randomized controlled trials have been completed, the majority of which have documented a positive impact on anxiety symptoms following participation in these interventions (e.g., Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Culhane-Shelburne, & Hepburn, 2012; Wood et al. 2009; Storch et al. 2015; Weston, Hodgekins, & Langdon, 2016). As is frequently the case in the early design and development of novel interventions, many of these studies focus on efficacy, and are conducted in academic settings. Although universities frequently offer cutting edge treatment opportunities via clinical trials, several factors (i.e. strict inclusion criteria, scheduling difficulties and transportation to specialty clinics) can prevent many families from accessing services. Even when families choose to go outside of academic settings, there is often a scarcity of qualified providers (Wainer et al. 2017).

Bridging the Research to Practice Gap

While clinical trials have demonstrated meaningful reductions in symptoms, simply making evidence-based treatment available to clinicians in community settings is insufficient to ensure ongoing use and eventual adoption of the treatments in new contexts (Dingfelder & Mandell, 2011). A range of factors contribute to the challenges that many organizations face in adopting evidence-based practices (EBPs) including practitioner (e.g. qualifications, interest and perceptions about EBPs) and organizational factors (e.g., incompatibility with the settings’ values and beliefs) (Beidas et al. 2011; Dingfelder & Mandell, 2011; Wood, McLeod, Klebanoff & Brookman-Frazee, 2015). If these variables are not adequately addressed, outright rejection of an intervention can occur, as well as haphazard and/or partial delivery of treatment programs which can lead to poor treatment fidelity, limiting the effectiveness of the treatment even when delivered (Elkins, McHugh, Santucci, & Barlow, 2011; Wood et al. 2015).

For treatments targeting the mental health symptoms of youth with ASD, little is known about the implementation (e.g., feasibility, effectiveness) of these interventions in other sites. In fact, lack of active dissemination strategies, or thoughtful ways to transport EBP for youth with ASD from one setting to another impedes the process (Wainer et al. 2017). More specifically, lack of compatibility between interventions developed in research settings and what may be feasible in practice settings no doubt contributes to the difficulty in transporting evidence based practice to the community (Wainer et al. 2017). Perceived complexity, as well as cultural insensitivity of the new intervention can also present barriers to eventual adoption of EBPs and are critical to consider when moving an intervention from university to community settings (Ratto et al. 2016).

There are added challenges in the implementation of interventions to address the mental health symptoms of youth with ASD, as there are no universally established guidelines detailing who can deliver the treatments, nor are there guidelines for how to train and supervise these practitioners (Wood et al. 2015). In treating comorbid anxiety in individuals with ASD, determining whether clinician experience with ASD is more important than experience with psychiatric conditions is important to consider. It may be equally critical to understand the best processes for training these providers (e.g., amount and methods of training). Thus, it is essential to develop appropriate parameters for training and treatment delivery given the high prevalence of anxiety in youth with ASD, coupled with poor access to appropriate interventions.

Implementation Efforts for Youth with ASD

The implementation of evidence based mental health interventions for children and adolescents with ASD in “real world” settings is in its infancy, with only a handful of studies that have begun to examine the implementation of EBPs targeting mental health symptoms in community settings. One such study examined the impact of training community mental health therapists to deliver EBP targeting challenging behaviors in school-aged youth with ASD (Brookman-Frazee, Drahota & Stadnick, 2012). Results indicated that the therapists delivered the treatment with good fidelity, and significant reductions in child problem behaviors were apparent following treatment participation. Although this study cannot serve as an exact precursor to the current study given the differences in treatment targets and providers, it does provide an initial example for how to maximize fit of an ASD intervention with existing practice (Wood et al. 2015). Information about successful treatment of anxiety in youth with ASD in community settings has not yet been studied.

Manualized Interventions

In the general pediatric population, the manualization of EBP has been a step towards supporting increased access of these treatments to community clinicians. These interventions are typically designed to target a range of symptoms including anxiety, depression, and social skill deficits in typically developing youth. Manuals are particularly useful to clinicians as they standardize intervention delivery, specify acceptable adaptations, and provide suggestions for trouble-shooting common problems that may arise during the course of the treatment (Kasari & Smith 2013). It is important to tailor trainings on the use and delivery of these manuals to the experiences and talents of the practitioners. Providing theoretical understanding of the treatment, combined with hands-on experiential activities is recommended (Beidas & Kendall, 2010).

Common efforts to disseminate treatments in the community have typically consisted of distributing manuals and only occasionally offering trainings (Sholomskas et al. 2005). Thus, it is critical to determine whether simply reading a manual is sufficient for delivering a treatment and obtaining optimal outcomes or whether adding clinician training improves outcomes. To address this question, Sholomskas et al. (2005) randomly assigned community clinicians to one of three training conditions to learn a manualized CBT intervention to treat substance abuse disorders. The study compared the effectiveness of a Manual Only condition, Manual Plus Access to a CBT Website, and Manual Plus Didactic Seminar and Ongoing Supervision. Results indicated that the clinicians’ ability to implement the CBT program accurately was superior for the two conditions that involved opportunities to obtain additional guidance (e.g., Manual Plus Seminar and Manual Plus Website), as compared to Manual Only (Sholomskas et al., 2005). There are no known studies that have systematically compared differential instructional strategies for manualized EBPs for treating anxiety in youth with ASD.

The purpose of the current study was to expand on previous research and explore the implementation of a group CBT intervention for anxiety in youth ages 8–14 with ASD (Facing Your Fears: Group Therapy for Managing Anxiety in Children with High-Functioning ASD; FYF; Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Nichols, & Hepburn, 2011) in outpatient clinic settings by examining optimal clinician training methods in anticipation of broad program implementation. Although there are a number of potential directions to consider when transporting an intervention from research to practice settings, the focus on practitioner training was selected because of the challenges in implementing EBPs with good integrity, and that processes for practitioner training and supervision are not clearly detailed (Wood et al. 2015). The successful completion of several treatment trials examining the efficacy of FYF, including a randomized controlled trial (Reaven et al, 2009; 2012) set the stage for this implementation project. Results of a previously conducted RCT indicated that in an intent-to-treat sample, 50% of youth who participated in the FYF program obtained a clinically meaningful positive treatment response, compared to 8.7% in the treatment as usual condition (Reaven et al. 2012).

Following the initial efficacy trials, phase one of the implementation project was conducted in Halifax, Nova Scotia where FYF was introduced to outpatient clinicians (professionals in psychology) treating youth with ASD and anxiety to evaluate effectiveness outside of the academic setting in which FYF was developed (Reaven et al. 2015). Results indicated that after a training workshop and participation in bi-weekly phone consultations, clinicians displayed excellent treatment fidelity and youth demonstrated significant reductions in anxiety following treatment (Reaven et al. 2015). Clinician critiques were incorporated into program revisions to enhance success for ongoing clinical practice, thus potentially maximizing the sustainability of the intervention in “real world settings” (Weisz, Chu & Polo, 2004). Thus, results from phase one set the stage for the current study.

Current Study

The primary aim of the current study was to determine the optimal training model for clinicians working with youth with ASD, but who were new to FYF. Three instructional conditions were compared: 1) manual only (Manual); 2) manual plus two-day workshop (Workshop); and 3) manual plus two-day workshop plus bi-weekly supervised consultation (Workshop-Plus). The effectiveness of each instructional method was measured via clinician implementation outcomes (CBT knowledge and treatment fidelity) and youth treatment outcomes (reductions in anxiety symptoms). It was hypothesized that the Workshop-Plus and Workshop conditions will be superior to the Manual condition on both implementation and youth treatment outcomes; it was also hypothesized that the Workshop-Plus condition will be superior to the other two instructional conditions as workshop participation paired with ongoing supervision is considered best practice (Beidas & Kendall, 2010).

Method

Participants

Two groups of participants took part in the study: Clinicians and youth with ASD and comorbid anxiety.

Clinicians

A total of 34 clinicians participated across the four sites. Inclusion criteria included students or professionals in mental health (e.g., clinical psychology, counseling psychology, or social work) or education (e.g., special education) working in University-affiliated outpatient clinics with youth with ASD. More specifically, clinicians were: (a) graduate students, clinical psychology interns, post-doctoral fellows in psychology, individuals with terminal master’s degree in a mental health or education discipline, or PhD-level clinical psychologists; and (b) were currently serving youth with ASD in outpatient settings1. Clinicians were excluded if they could not commit to the project for the duration of at least one year.

Mean age of the clinicians was 33.56 years (SD = 9.3). The majority of clinicians were female (n=32) and Caucasian (n=30) with 3 clinicians identifying as Black/African-American and another self-identified as “other.” Eighteen clinicians held a terminal Master’s degree at the time of consent (53%), 14 held a Ph.D. (41%) and 2 held a Bachelor’s degree with some graduate training (e.g., Master’s or doctoral degree graduate students, interns; 6%). Clinicians had an average of 3.4 years of experience using CBT approaches (SD = 3.2), 7.6 years (SD = 7.6) of experience working with youth with ASD and 4.6 (SD = 4.6) years of experience working with youth who present with clinical anxiety (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinician Demographic and Baseline Characteristics by Training Condition

| Characteristic | Manual (N=11) |

Workshop

only (N=11) |

Workshop

Plus (N=12) |

Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | χ 2 = 1.02 | .60 | |||

| Female | 11 (100%) | 10 (90.6%) | 11 (91.7%) | ||

| Male | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (8.3%) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | χ 2 = 2.17 | .70 | |||

| African | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (8.3%) | ||

| American/Canadian | |||||

| Native American | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Caucasian | 10 (90.9%) | 9 (81.8%) | 11 (91.7%) | ||

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Other | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Highest Level of Education | χ 2 = 9.29 | .054 | |||

| Bachelor’s | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (8.3%) | ||

| Terminal Masters | 7 (63.6%) | 2 (18.2%) | 9 (75.0%) | ||

| Professional Degree | 4 (36.4%) | 8 (72.7%) | 2 (16.7%) | ||

| Years of CBT experience | 5.1 (4.8) | 2.7 (1.8) | 2.8 (2.4) | F(2,25)=15.30 | .23 |

| Range | 0.5–12 | 0–6 | 0–8 | ||

| Years of Anxiety experience | 7.9 (6.6) | 3.6 (2.3) | 2.6 (1.5) | F(2,25) = 5.34 | .01 |

| range | 2–25 | 0–8 | 1–6 | ||

| Years of ASD experience | 8.2 (6.8) | 7.1 (9.5) | 7.4 (7.1) | F(2, 25) = 0.05 | .95 |

| range | 1–25 | 1–34 | 0.3–28 |

There were no baseline clinician differences for gender, ethnicity, highest level of education, years of CBT experience, or years working with ASD. However, clinicians assigned to the Manual condition had significantly more experience in working with youth with anxiety disorders (M=7.9 years, SD = 6.6 years) than clinicians assigned to the other two conditions: Workshop (M=3.6 years, SD = 2.3 years) and Workshop-Plus (M=2.6 years, SD = 1.5 years), F(2, 31) = 5.34, p = .01,, ωp2 = .20. Further, when comparing clinician experience across sites, it was apparent that clinicians at one of the sites, (Site 2) had significantly more experience working with youth with ASD than clinicians at any of the other sites: M = 14 years, SD = 11.6 years; F(3, 30) = 3.99, p = .02,, ωp2 = .21 (Site 1: M=2.7, SD = 1.7; Site 3: M=6.2, SD= 3.7; Site 4: M=5.1, SD= 3.8). There were no differences in clinician experience working with youth with anxiety disorders across sites.

Youth participants

Youth were between the ages of 8–14 years with ASD and clinical anxiety, and participated in the study with at least one parent. Families were recruited from four outpatient clinic settings serving individuals with ASD in the United States via Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved announcements, electronic flyers, practitioner referrals and word of mouth. Informed consent and assent was obtained for all clinician, child, and caregiver participants prior to collecting data. All four sites were University-affiliated and were considered regional leaders in the assessment and treatment of ASD.

The Intent to Treat (ITT) sample included 91 youth. Inclusion criteria were: (a) chronological age of 8–14 years and living with a caregiver who could provide informed consent to participate; (b) diagnosis of ASD, as determined by a score above the spectrum cutoff on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2012) and the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Berument, Rutter, Lord, Pickles, & Bailey, 1999); and a clinical diagnosis of ASD, as determined by a review of history and current clinical presentation by a clinical psychologist. (c) estimated Verbal IQ of 80 or above, as determined through standardized cognitive testing using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler, 2002) or an equivalent measure of intelligence administered within the past 2 years; (d) ability to read at a second-grade level, as determined by the Letter-Word Identification and Passage Comprehension subtests of the Woodcock-Johnson Achievement Tests-Third Edition (WJ-III; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001); (e) clinically significant symptoms of anxiety defined as a score above the clinical significance cutoff on separation (Separation Anxiety Disorder; (SEP)), social (Social Anxiety Disorder; (SOC)); and/or generalized anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder; (GAD)) subscales of the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED)-Parent Version (Birmaher et al., 1999); and (f) clinically significant symptoms of either SEP, GAD, or SOC and this impairment is “primary” or more functionally significant than another disorder (such as depression) as determined by an independent clinician evaluator (CE) using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Parent (ADIS-P; Silverman & Albano, 1996). Children currently taking medications were eligible for the study; however, they were required to be on a stable dose of psychiatric medication, i.e., at least one month at the same dosage prior to the baseline assessment, and were also asked to maintain the same dosage of medication over the course of the study, per procedures in previous studies (Reaven et al. 2012; Wood et al. 2009). Medication status was confirmed at baseline. Weekly medication tracking logs indicated that 6% of participants made changes to medications during the intervention; however, notes indicated that none of the changes were due to increases in symptoms of anxiety.

Children were excluded if (a) their family was not fluent in English; (b) their family could not commit to attending 11 of 14 sessions within the intervention period; (c) they presented with psychosis, severe aggressive behavior, or other severe symptoms that were considered a clinical priority for more intensive treatment; (d) their family intended to seek additional psychosocial treatment for anxiety during the 4 month study period; and (e) they were not able to separate from their parent for a minimum of 30 minutes during the pre-intervention assessment visits. If a child was not eligible to participate in the study, the family was referred to other therapeutic services.

Pre-treatment comparison of child participants

The comparability of the child participants by training condition at baseline was examined using one-way ANOVAs or chisquare. There were no pre-treatment differences between the three conditions on age, ethnicity, gender, overall anxiety symptoms, number of anxiety diagnoses, or IQ; however, there were more Asian-American and African-American families assigned to the Workshop-Plus condition than would be expected by chance (Asian-American standardized residual 3.7; African-American standardized residual 2.0). In addition, fewer Caucasian families were assigned to the Workshop-Plus condition than would be expected by chance (Caucasian-standardized residual −2.6). No other baseline differences were found. See Table 2 for child demographics.

Table 2.

Child Demographic and Baseline Characteristics by Training Condition

| Characteristic | Manual (N=33) |

Workshop

only (N=30) |

Workshop

Plus (N=28) |

Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | χ 2 = 3.37 | .19 | |||

| Female | 3 (9.1%) | 4 (13.3%) | 7 (25.0%) | ||

| Male | 30 (90.9%) | 26 (86.7%) | 20 (71.4%) | ||

| Not reported | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.5%) | ||

| Race | χ 2 = 40.81 | <.001 | |||

| African | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (3.3%) | 5 (17.9%) | ||

| American/Canadian | |||||

| Native American | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.5%) | ||

| Caucasian | 29 (87.9%) | 24 (80.0%) | 7 (25.0%) | ||

| Asian | 2 (6.1%) | 2 (6.7%) | 14 (50.0%) | ||

| Other/Biracial | 1 (3.0%) | 3 (10.0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Not reported | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.5%) | ||

| Ethnicity | χ 2 = 7.64 | .11 | |||

| Hispanic | 1 (3.0%) | 4 (13.3%) | 1 (3.5%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 32 (97.0%) | 25 (83.3%) | 26 (92.9%) | ||

| Not reported | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (3.5%) | ||

| Age (months) | 132.9 (20.4) | 130.8 (27.6) | 135.5 (19.5) | F(2, 68) = .23 | .80 |

| Full IQ | 99.4 (14.64) | 105.5 (14.5) | 106.4 (18.1) | F(2, 84) = 1.79 | .17 |

| Number of anxiety diagnoses | 4.6 (1.4) | 5.0 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.9) | F(2, 87) = 1.23 | .61 |

Procedure

This study was completed in compliance with the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus) and the IRB of each of the four sites. Research assistants from local sites explained the study to interested families, reviewed the inclusion criteria and conducted a brief screen for eligibility. If the child was potentially eligible, the family participated in one or two sessions in which they completed ASD specific diagnostic measures, and cognitive and academic assessments. If a child met ASD/cognitive qualification criteria across measures, the parent was invited to complete a semi-structured psychiatric interview (ADIS-P) to obtain more detailed information regarding the presence of mental health conditions.

The study consisted of a 3-group parallel design where 9 teams (3 per year) of 3 clinicians were randomized via a Latin square procedure to receive one of three instructional conditions: 1) Manual, 2) Workshop, 3) Workshop-Plus (see descriptions below). The Latin square was constructed so that each training condition ultimately occurred only once in each site, and once per year. However, with a such a small array (3×3) we would have needed six condition orders to ensure that each condition occurred only once before and once after each other condition. Therefore, given the logistical constraints of this study, a random number generator was used to select three condition orders from all possible permutations while still ensuring that each condition occurred only once per site and per year.

Each site was assigned to an instructional condition for a full year, and the same 3 member clinician team was required to deliver treatment for the duration of the year. For the first year of the project, teams at each site delivered FYF to two groups of 3–5 children with ASD and anxiety. New teams were recruited at each site for each year, thus each team only participated in one training condition. For the second and third years of the project, the teams delivered FYF to three groups of children, for a total of 24 cohorts across the 3-year project. Three sites were part of the original project. However, one site encountered difficulties with recruitment during the first year, so it was mutually decided that they would no longer participate in the project and an additional site (Site 4) was recruited to participate in years two and three.

FYF Intervention

The FYF program is a 14-week program delivered in multi-family groups, with each session lasting 1 ½ hours. Large group time, parent-child dyads, and separate parent and child group meetings comprise the weekly sessions. Of the three clinicians assigned to each group cohort, one clinician primarily works with the parent group, and the other two primarily facilitate the child group when the parents/children met simultaneously. Three FYF treatment manuals were used in this study: a parent workbook, a child workbook, and a facilitator manual (Reaven et al., 2011). Group sessions are interactive, activity-based, and divided into two, seven-session intervention blocks: (1) psychoeducation of anxiety and introduction to common CBT strategies; and (2) direct practice of specific tools and strategies (i.e. deep breathing, positive coping statements, emotion regulation techniques and graded exposure) to treat anxiety. Small “homework” assignments reinforce core concepts and allow for exposure practice at home. Parental anxiety and parenting style are directly discussed.

Similar to other CBT treatment programs for youth with ASD and anxiety, modifications to the delivery of the core concepts are essential, particularly given the social, emotional, communicative, and cognitive challenges of children with ASD (Moree & Davis, 2010). Modifications incorporated evidenced-based practices for youth with ASD including visual supports and video modeling (Wong et al., 2015). Visual supports included the use of written schedules, worksheets, and multiple-choice lists. Video modeling was used to support “hard to teach” concepts and to enhance the generalization of skills across settings. Instructions and activities for parents are interwoven throughout each group session. All FYF sessions were digitally video-recorded and sent as encrypted files to the Colorado site, for purposes of coding fidelity as well as providing consultation for clinicians in Workshop-Plus condition.

Instructional Conditions

The three instructional conditions were: 1) Manual – FYF manual only; 2) Workshop – FYF manual plus a 2 day intensive workshop; 3) Workshop-Plus – FYF manual plus a 2 day intensive workshop, and participation in bi-weekly phone conferences with FYF developers. A comparison of these three conditions was selected because dissemination of evidence-based interventions have typically involved distribution of manuals and/or participation in workshops without ongoing supervision (Sholomskas et al. 2005). Workshop-Plus was included as a condition because as noted above, workshop participation paired with ongoing supervision is considered best practice (Beidas & Kendall, 2010).

Workshop

All clinician teams that were assigned to either the Workshop or Workshop-Plus conditions were required to attend a locally provided 2-day workshop. Clinicians completed an assessment of CBT knowledge pre- and post-workshop. In keeping with evidence-based adult learning strategies (Wood, McLeod, Klebanoff, & Brookman-Frazee, 2015) and research on training clinicians through a Declarative-Procedural-Reflective model (Bennett-Levy, 2006), workshop content focused on strategies to increase declarative understanding and procedural skills and included didactic presentations, small group activities, videotaped examples, role-playing exercises, performance feedback and session-by-session reviews.

Phone consultation

In the Workshop-Plus condition, twice monthly, hour-long phone consultations were provided by two of the authors (JR or AB-S) to each clinician team for the duration of the study. Recorded sessions were viewed by the aforementioned authors prior to phone consultation. The consultation format involved opportunities for reflection on group facilitation (Bennet-Levy, 2006) and included the following components: (a) question-and-answer period regarding the FYF sessions that occurred since the last phone consultation; (b) feedback regarding strengths of facilitation, missing elements, and suggestions for delivery of session content; and (c) plan for the upcoming FYF sessions. Clinicians in the other conditions did not receive feedback of any kind from the authors.

Measures

Eligibility Measures

Diagnosis of ASD

Diagnostic status was determined by expert clinical review of the ADOS-2 (Lord et al., 2012), the SCQ (Berument et al. 1999) and clinician review of history and current presentation. The ADOS-2 is a semi-structured, play-based direct assessment of social and communicative behaviors indicative of ASD and is the “gold standard” for diagnosing ASD (Lord et al., 2012). Clinicians administering the ADOS-2 were research reliable. The SCQ is a 40-item, parent report checklist focused on current and lifetime symptoms of ASD. Derived from the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord, Rutter, & Couteur, 1994), the SCQ has strong convergent validity with the much longer clinical interview.

Screening for cognitive functioning and reading abilities

Participants without standardized cognitive assessment within the past 2 years were administered the WASI (Wechsler, 2002). All participants were administered two reading subtests from the WJ-III (Woodcock et al., 2001) to confirm acquisition of pre-requisite reading skills to participate in FYF. A reading grade level of at least second grade was required for inclusion.

Screening for anxiety symptoms

The SCARED–Parent version (Birmaher et al., 1999) is a 41-item inventory comprised of five anxiety subscales (Panic, GAD, SEP, SOC, and School Anxiety) and a total score. Parents reported on symptoms over the past month. The SCARED demonstrates excellent psychometric properties in typically developing youth (Birmaher et al., 1999; Hale, Crocetti, Raaijmakers, & Meeus, 2011). Results from a recent study confirm the 41-item measure’s five-factor structure and suggest good sensitivity (.71) and specificity (.67) among parents of youth with ASD (Stern, Gadgil, Blakeley-Smith, Reaven & Hepburn, 2014). Within the present sample, internal consistency of the domains of the SCARED is adequate and ranged from .72 to .88 for both the parent and child report.

Implementation Outcomes

Clinician Characteristics

A brief questionnaire was completed by clinicians to provide demographic information and to track their years of experience implementing CBT strategies and working with children with ASD. There was a wide range of experience among clinicians working with children with ASD or with children with anxiety, and type of experience did not necessarily overlap. Determining how to understand the impact of clinician experience is complicated by the fact that some of the clinician group cohorts were comprised of one very senior clinician and two novices, so using a mean level of experience could render an inflated mean score. In order to manage this challenge, we averaged the highest level of ASD and anxiety experience at each site for each instructional condition to use as a covariate in the statistical models.

Assessment of CBT knowledge

A 20-item multiple-choice test was used to evaluate clinicians’ knowledge of CBT before and after attending the training workshop. Two similar but non-identical versions of the assessment were administered prior to and following the workshop. Although participants in the Manual condition were asked to take the Knowledge test prior to and following the reading the manual, this occurred only inconsistently (perhaps due to miscommunication on the part of the authors); therefore, data from Manual was not included in the analyses.

Treatment fidelity measure

A treatment fidelity measure, adapted from the Yale Adherence and Competence Scale (YACSII) Guidelines (Nuro et al., 2005) and applied in previous studies (Reaven et al., 2014), was used to assess the absence/presence of core treatment components on a session-by-session basis. In addition, a global rating of quality was completed for every modality for every session (e.g. large group, parent/child dyads, parent group, child group) via videotape by two of the FYF developers (JR, AB-S). Ratings were based on a Likert scale ranging from poor (1) to excellent (5) quality. The quality rating is a global score encompassing therapeutic alliance, therapist expertise, and competence in the delivery of core treatment content for each modality. Twenty-five sessions (7.4%) were coded by both raters. Inter-rater reliability was 93%.

Treatment Outcomes

ADIS-P

The ADIS-P (Silverman & Albano, 1996) was the primary outcome measure and was administered pre- and post-intervention, by the CE who was a member of the research team, but did not deliver the intervention. The ADIS-P is a semi-structured psychiatric interview that assesses the presence of anxiety disorders and other co-occurring mental health conditions. Diagnostic status of target anxiety disorders (e.g., SOC, GAD, SEP, and Specific Phobia (SpP)) was a primary focus of the intervention2. The ADIS-P demonstrates strong psychometric properties, including good test–retest reliability for diagnoses and symptom scales (Silverman et al., 2001), as well as convergent validity with other anxiety measures (Lyneham & Rapee, 2005; Wood, Piancentini, Bergman, McCracken, & Barrios, 2002). Only the parent version of the ADIS-P was administered, in keeping with other research studies examining anxiety in youth with ASD (Storch et al. 2015). The CE conducted the ADIS-P with the parent, determined diagnostic classifications across DSM-IV categories, and provided summary codes of severity and interference, called “Clinician Severity Ratings” (CSRs: 0 = no symptoms, 8 = very severe impairment) for all diagnoses. The CE also determined the “primary” diagnosis (e.g., yielded the highest CSR on the ADIS-P).

The Clinical Global Impressions Scale - Severity and Improvement (CGIS-S & CGIS-I; Guy & Bonato, 1970) were completed to assess overall severity and improvement of the child’s anxiety on a 7-point scale, with lower scores indicating less severity (CGIS-S) and more improvement (CGIS-I), respectively. The CE assigned a CGIS-S score at pre- and post-treatment, and a CGIS-I score at post-treatment. The CGIS-I ratings were compiled by each CE after the participants had completed all study activities. These ratings were derived in a manner similar to the methods described in previous studies (Walkup et al., 2008; Wood et al., 2009). The CE reviewed the ADIS-P obtained pre- and post-treatment, and assigned a rating of 1–7 concerning the overall impression of improvement (1 = “very much improved”; 4 = “no change”; 7 = “very much worse”). Children who obtained a CGIS-I of 1 or 2 were considered to be positive treatment responders.

ADIS-P administration training was conducted by AB-S with clinicians from all four sites. Training criteria included scoring above 80% reliability on clinical diagnoses and CSRs on three videotaped administrations of the ADIS-P and three live administrations (serving as the interviewer). The ADIS-P was administered by clinical psychologists at two sites (n=2) and by advanced trainees in psychology at two sites (n=4) in a standardized manner within 6 weeks pre and post-intervention. Ongoing supervision from AB-S was provided on all aspects of ADIS-P administration and interpretation as necessary. A subsample of 29% of CSRs was coded by a second coder to ensure reliability of the scores. Interclass correlations (ICC) for all subscales was high: GAD = .81; social phobia =.89; separation anxiety =.84; specific phobia =.86. We also double coded 8% of the CGIS-Improvement scores. Percent agreement for this measure was 100%.

Analysis Plan

Implementation outcomes

The clinician sample was characterized by calculating descriptive statistics of clinician demographics including gender, highest level of education, years of CBT experience, years of experience in working with children with anxiety disorders and years of experience in working with children with ASD. The effectiveness of instructional condition was examined in two different ways: a) changes in CBT Knowledge following clinician participation in the training workshop, and b) adherence to the FYF intervention. Clinician knowledge of CBT was compared with a repeated measures ANOVA with Time (knowledge before training vs. knowledge after training) as a within subjects factor, and training condition (Workshop vs. Workshop-Plus) as a between subjects factor. The Manual condition was not included since participants only inconsistently completed the test. Comparisons between study sites were also examined to determine impact of site differences, if present.

Fidelity of implementation was assessed in two ways and was similar to procedures used for the assessment of FYF treatment adherence in previous studies (Reaven et al., 2015): a) calculating the percentage of core treatment components that were present across all sessions and comparing that proportion between training groups using chi-square, and b) calculating global quality rating for each treatment modality for each session and comparing those ratings by group using a one way ANOVA.

Treatment Outcomes

The child participant sample was analyzed using an intent-to-treat (ITT) approach. All children who met eligibility criteria and began treatment were included in the analyses, even if they dropped out prior to finishing the study. The ITT sample was characterized by calculating descriptive statistics of child demographics at baseline including gender, age in months, race and ethnicity, and degree of anxiety symptoms as measured by the child and parent SCARED total scores, and number of anxiety diagnoses from the ADIS-P. Characteristics among training conditions using ANOVAs or chi-squares were compared to determine how similar the groups were at baseline.

A series of linear mixed models were used to explore differences in child outcomes among the three instructional conditions. Linear mixed models include both fixed and random effects and are analogous to repeated measures ANOVA or a general linear model with compound symmetry (Zuur, Ieno, Walker, Saveliev, & Smith, 2009). This approach retains the benefits of more complex modeling techniques, such as those used in hierarchical linear modeling and accommodates the highly nested nature of these data.

Separate models were fit for each of the four anxiety diagnoses as measured by the ADIS-P. CSRs obtained from the ADIS-P at the two time points were used as the dependent variable. Training condition (Condition) and anxiety symptoms before and after treatment (Time) were entered as fixed factors, including the interaction of these variables. In all models, we included the average number of years of experience with ASD and anxiety of the most highly trained clinicians in the training cohort as a random factor to account for variability in clinician experience. In this approach, the test of interest is the interaction between Time (pre vs post CSR) and Condition (Manual vs. Workshop vs. Workshop-Plus) and are corrected for variability in clinician experience. Fixed main effects were evaluated if the interaction was not significant. This analysis is similar to previous research on this intervention (Reaven et al. 2012). We also calculated ωp2 (partial omega squared) as our measure of effect size which represents the amount of variance in the outcome variable accounted for by given factor, accounting for all other factors (Olejnik & Algina, 2003). This measure is preferable because it is less biased than ηp2 (partial eta squared) and can be generalized to numerous research designs (Lakens, 2013). Significance was set at .05 in all cases; effects with p values between .10 and .05 are also reported as potentially interesting.

Next, the proportion of children who at pre-treatment met diagnostic criteria for one of the four main anxiety diagnoses at pre-treatment, and those who no longer met criteria for these diagnoses following treatment, was explored. Chi-square tests were used to explore differences in the proportions of diagnoses lost across conditions.

Finally, the overall level of child improvement in primary anxiety diagnosis was assessed by comparing CGIS-I ratings across instructional conditions and sites. Chi-square tests were used to examine differences.

Results

Implementation Outcomes

Assessment of CBT knowledge

There were no pre-workshop differences in CBT Knowledge for the clinicians in either the Workshop or Workshop-Plus conditions, F(1, 21) = 0.002, p = .96. There was no interaction by condition and time, F(2, 22) = .70, p = .51,, ωp2 = −.02. A repeated measures ANOVA with time (pre vs post training) as a within subjects factor and training condition (Workshop vs Workshop-Plus) revealed there was no interaction between time and conditions, or main effect for condition. However, there was a strong effect for time, F(1, 18) = 19.8, p < .001, ωp2 = .48, indicating that clinicians in both instructional conditions demonstrated significant improvements in CBT knowledge after attending the training workshop.

Treatment fidelity

Nine teams of clinicians delivered the FYF intervention to 24 cohorts across three years. Eight cohorts were assigned to each instructional condition. All instructional conditions exceeded the minimum standard for treatment fidelity (80%) – Manual – 89.9%; Workshop – 92.8%; and Workshop-Plus – 93.2%. However, there was a difference in the proportion of adherence to the core components by training condition, X2(2) = 11.94, p = .003. Examination of standardized residuals in the contingency table revealed that clinicians in the Manual condition obtained significantly lower fidelity ratings than would be expected by chance (Standardized Residual = 2.6). Clinicians in the two workshop conditions did not perform differently than would be expected by chance.

Average global ratings of quality were obtained on a Likert rating scale between 1 (low) and 5 (high) for each modality and differed among training conditions, F(2, 1374)=50.55, p<.0001, ωp2 = .07. Tukey HSD post hoc comparisons revealed that clinicians in the Manual condition were rated as significantly lower in quality of treatment delivery (M = 4.26, SD = .95) compared to clinicians in the Workshop (M = 4.67, SD = .57), p < .001, and Workshop-Plus (M = 4.69, SD = .57), p <.001 conditions. Again, there were no statistical differences in quality ratings for clinicians in either workshop condition.

Treatment Outcomes

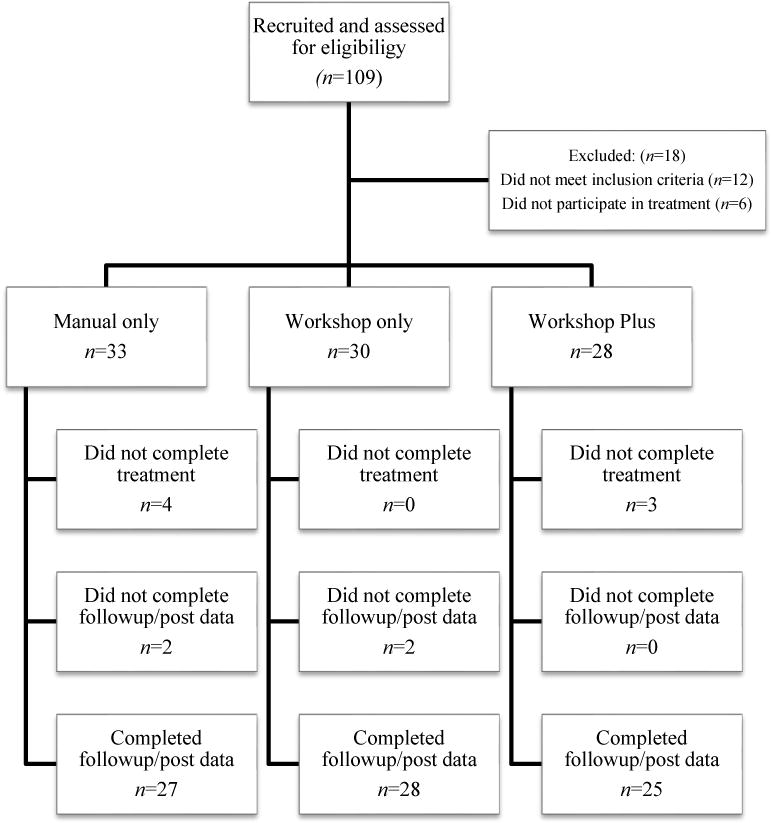

There were 109 children who were consented to participate in the study across sites. One child did not complete eligibility measures, and another 11 did not meet eligibility criteria; thus, 97 children met study criteria for participation. Six children dropped out of treatment prior to beginning FYF, and another 7 dropped out of treatment prior to completion. Eighty-four children completed FYF, but parents of the four children did not complete post treatment assessments. See Figure 1 for Consort Table.

Figure 1.

Clinician Severity Ratings

A series of linear mixed models was used to examine changes in CSRs for the four main anxiety diagnoses. In all models, the CSR scores were the dependent variable; time (pre vs. post treatment) and condition (Manual vs. Workshop vs. Workshop-Plus) were entered as fixed factors. Due to the differences that were found in clinicians’ experience by site, the clinician experience was included as a random factor in all models. See Table 3 for pre- and post-CSRs.

Table 3.

Clinician Severity Ratings (CSRs) at pre and post treatment by training condition.

| Manual (N=33) | Workshop Only (N=30) | Workshop Plus (N=28) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range |

| Separation Anxiety | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.58 (1.31) | 3–7 | 3.27 (1.49) | 1–6 | 4.67 (1.12) | 3–6 |

| Post treatment | 1.14 (1.98) | 0–7 | .93 (1.87) | 0–5 | 1.84 (2.21) | 0–6 |

| Social Phobia | ||||||

| Baseline | 5.04 (0.92) | 3–7 | 4.93 (1.02) | 3–7 | 5.17 (0.98) | 4–7 |

| Post treatment | 3.67 (1.90) | 0–6 | 3.00 (2.02) | 0–5 | 4.28 (1.65) | 0–7 |

| Specific Phobia | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.24 (0.93) | 3–6 | 4.58 (0.88) | 3–6 | 4.52 (0.77) | 3–6 |

| Post treatment | 2.70 (1.75) | 0–5 | 2.93 (1.88) | 0–5 | 3.04 (2.30) | 0–6 |

| GAD | ||||||

| Baseline | 5.27 (0.87) | 4–7 | 5.00 (1.09) | 2–7 | 5.39 (0.72) | 4–7 |

| Post treatment | 3.48 (2.21) | 0–6 | 2.71 (2.21) | 0–6 | 3.76 (2.07) | 0–6 |

Significant reductions in anxiety severity were apparent across three of the four anxiety diagnoses over time. See below for specific results by diagnosis.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

Seventy-nine (79) children met diagnostic criteria for GAD pre-treatment (CSR≥4) across the three instructional conditions. There was a significant effect for Time, F(1, 59.37) = 76.02, p<.0001, ωp2 = .64, but no effect for the Time by Condition interaction or a main effect for Condition.

Social Phobia (SOC)

Seventy-seven (77) children met diagnostic criteria for SOC pretreatment. There was a significant effect for time, F(1, 47.73) = 21.48, p <.0001, ωp2 = .29. There was no Time by Condition interaction or main effect of Condition.

Specific Phobia (SpP)

Sixty-five (65) children met diagnostic criteria for SpP pretreatment. There was a significant effect for time, F(1, 73.23) = 17.25, p < .0001, ωp2 = .18. Condition was not significant in this model; however, the Time by Condition interaction approached significance, F(2, 72.95) = 3.02, p = .06, ωp2 =.05. Examination of the mean differences between conditions revealed that the Manual condition improved more than the Workshop Plus condition, p = .048, but no other effects were significant.

Separation Anxiety (SEP)

Twenty-three (23) children met diagnostic criteria for SEP at pre-treatment. The effect of time approached significance, F(1, 21.95) = 3.57, p = .072, ωp2 = .10. No other effects were observed for this outcome.

Diagnostic status of four main anxiety disorders

Of the 79 children who met criteria for GAD pre-treatment, 31 children (39.2%) no longer met criteria for this diagnosis post-treatment and there were no differences among instructional conditions: χ2(2) = 2.94, p = .23. Of the 77 children who met criteria for SOC pre-treatment, 22 children (28.6%) lost the diagnosis post-treatment and there were no differences between instructional conditions, χ2(2) = 3.46, p = .18. Of the 65 children who met criteria for SpP pre-treatment, 27 (41.5%) lost the diagnosis following treatment, and there were no differences among conditions, χ2(2) = 5.1, p = .78. Finally, of the 23 children who met criteria for SEP pre-treatment, 12 (52.2%) lost the diagnosis post-treatment and there were no differences between conditions, χ2(2) = 0.07, p = .97.

CGIS-Improvement ratings

Eighty children completed the FYF treatment and post-intervention ADIS-Ps. There were no statistically significant differences in number of youth who met criteria for a clinically meaningful outcome across instructional conditions, χ2(2) = 1.63, p = .45: Workshop-Plus – 25.9%; Workshop – 44.4 %; and Manual – 29.6%. The following percentages reflected the number of youth in each instructional condition that “somewhat improved” following treatment: Workshop-plus – 40%; Workshop – 35.7%; and Manual – 37%. The following percentages represent the number of youth whose symptom severity showed no real change following treatment participation: Workshop-Plus – 32%; Workshop – 21.4%; and Manual – 33.3%. None of the children experienced a worsening of anxiety symptoms following treatment.

Site differences

In order to determine whether there were significant differences in treatment outcome across the four participating sites, CGIS-I rating were compared using a chi-square. The percentage of youth who met criteria for a clinically meaningful outcome across sites was as follows: Site 1 – 66.7%; Site 2 – 43%; Site 3 – 38% and Site 4 – 5%. There was a difference in proportions among sites, χ2(3) = 11.68, p = .009. Review of the standardized residuals revealed that Site 4 had a lower proportion of children who significantly improved than would be expected by chance (−2.2). Follow up t-tests between sites evaluating symptom severity at baseline revealed that children at Site 4 had significantly lower scores than other sites for SEP (p-values range between .03 and .002) and GAD (p-values range between .01 and .0004), which could explain this finding. No other cells had a standardized residual greater than 2.

Discussion

This multi-site trial is the first known study to systematically examine training methods for clinicians inexperienced in a manualized group CBT treatment (FYF) for youth with ASD and anxiety. Implementation and treatment outcomes were compared across instructional condition.

Implementation outcomes

Hypotheses regarding implementation outcomes were generally confirmed. Significant improvements in CBT knowledge occurred following the workshop for participants across the two Workshop conditions. Similar results occurred in previous studies (Reaven et al. 2015) indicating that the training workshop may be effective for improving CBT knowledge in clinicians learning FYF. Furthermore, clinicians in all three instructional conditions obtained excellent treatment fidelity for presence of core FYF components, and above the minimum standard for acceptable treatment fidelity. However, significant differences were apparent between conditions as the clinicians in both Workshop conditions demonstrated significantly better adherence to protocol compared to clinicians in the Manual condition. Similar findings were apparent for quality of treatment delivery. Although clinicians in all three conditions delivered FYF with high quality, clinicians in both Workshop conditions delivered FYF with significantly higher quality compared with clinicians in the Manual condition; there was no advantage of Workshop-Plus in measures of fidelity.

Treatment Outcomes

There were no significant differences between instructional conditions on treatment outcomes, contrary to our hypotheses that youth in the Workshop conditions would display superior outcomes, and that youth in Workshop-Plus would yield even greater reductions in anxiety symptoms. However, significant reductions in anxiety severity were observed following treatment for three of the four primary anxiety diagnoses across instructional condition. In addition, a number of youth lost their diagnoses following treatment at rates that ranged from a low of 29% for SOC to a high of 52% for SEP. Finally, youth who met criteria for a clinically meaningful outcome (CGIS-I of 1 or 2) ranged from a low of approximately 26% to a high of 44%, although differences across instructional conditions were not significant. Notably, these rates are lower than what were obtained in the previous RCT (50% clinically meaningful treatment response; Reaven et al. 2012) However, given that implementation trials often involve more uncontrolled variables and unforeseen adaptations these less robust outcomes are not surprising (Craske et al., 2009, Weisz et al., 2004; Wood et al. 2015). Efforts to improve these rates are essential to consider and may begin with strengthening some aspects of the workshop, such as emphasizing strategies for managing behavioral challenges as well as delivery of FYF in a group setting.

Implications of the Results

Results indicated that clinicians across instructional conditions could deliver FYF with excellent adherence to protocol and with excellent quality. Participation in a workshop appeared to benefit clinicians as measures of treatment fidelity were superior for clinicians assigned to both Workshop conditions. The extent to which the statistical differences in treatment fidelity between conditions reflected a meaningful difference is unclear, particularly because although significant reductions in anxiety severity were apparent, including change in diagnostic status, there were no significant differences across instructional condition. Overall, these results are encouraging and may indicate that the FYF manual is indeed user-friendly, as clinicians are able to “pick it up” and not only effectively deliver the program, but yield significant reductions in anxiety symptoms.

The absence of more marked differences in fidelity across instructional condition, could be because practitioners in the Manual condition had significantly more experience working with youth with anxiety disorders (clinicians in Manual condition had on average 7.9 years of experience with anxiety, compared to 3.6 years in Workshop and 2.6 years in Workshop Plus), potentially washing out expected differences. Perhaps a more refined measure of treatment fidelity would yield important differences between training conditions, particularly on difficult to deliver intervention components such as graded exposure.

Additionally, there appeared to be no clear advantage to the Workshop-Plus condition. These results are somewhat puzzling, as it was hypothesized that both Workshop conditions would yield greater reductions in anxiety symptoms compared to youth in the Manual condition, and that youth in the Workshop-Plus would yield the most reductions in anxiety symptoms. There may be several explanations for these findings. As noted above, greater experience in working with anxiety disorders as demonstrated by practitioners assigned to the Manual condition may have enhanced the effectiveness of clinicians within this condition, potentially accounting for the unexpectedly positive treatment outcome for youth in this condition. Additionally, the FYF manual was comprised of core CBT content that may have been familiar to clinicians employed in university clinics. Thus, procedural knowledge may have been high to begin with, and the details provided in the manual regarding the application to youth with ASD may have been sufficiently clear to support good adherence to protocol, rendering ongoing supervision less necessary. Challenges in capturing the entirety of each group session on video (e.g., filming all participants engaged in exposure practice), may have also limited the usefulness of consultation, particularly if the supervisor was unable to view portions of the session. Finally, other factors such as therapeutic alliance (Chu, Suveg, Creed & Kendall, 2010), group cohesion, culture and climate of the selected clinics (Dingfelder & Mandell, 2011) may be important to explore, particularly to determine whether these factors played an unexpected role in the Workshop-Plus condition.

By consenting to participate in this study the clinicians knew they were being videotaped and that their performance was being evaluated. All clinicians at each site were required to deliver the treatment to completion, and each outpatient clinic agreed to provide sufficient infrastructure (e.g., administrators supported clinicians’ time on the project, provided access to recruit patients from clinical settings, permitted access to treatment rooms, etc.) for treatment delivery. These same expectations and supports may not occur in the “real world”. Without mandatory participation, it is difficult to say that clinicians who attend a workshop or pick up a manual on FYF would implement with as high fidelity as those required to participate in this study. Perhaps the most parsimonious explanation is that ongoing consultation may not have substantially enhanced clinician ability to deliver FYF, and that attending a Workshop may be sufficient in some circumstances.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations in this study. The clinicians all worked in clinics that were affiliated with Universities and may be more skilled in working with specialty populations and diagnosis-specific interventions than practitioners working in other community settings. Thus, generalizability of these findings is limited to university-affiliated providers with at least some experience working with youth with ASD. In fact, for the most part, the clinicians in this study were well educated and presented with good experience, which may have contributed to lack of differences across instructional conditions. Additionally, although information regarding experience with CBT, as well as work with youth with ASD or anxiety was collected, we did not specifically inquire about CBT experience with anxiety, nor did we ask about the nature of graduate experience, pre/post-doctoral clinical training or experience with group therapy. CBT Knowledge tests were not consistently given to clinicians in the Manual condition, making it impossible to know the extent to which participation in the Workshop conditions would have improved CBT knowledge above and beyond just reading the manual. Moreover, it is plausible that there were subtle effects that we unable to detect given our sample size. Fidelity ratings were completed by two of the study authors who were not blinded to instructional condition, and although the CEs who completed ADIS-P interview at each site did not participate in the treatment, they too, were not blinded to instructional condition. Lack of a no-treatment comparison group also represents a notable limitation when interpreting the results. Finally, at the writing of this paper, there were no follow up data on implementation outcomes or maintenance of treatment outcomes, so statements regarding the long term sustainability of FYF cannot be made.

Summary and Future Directions

The results of the current study suggest that clinicians with at least some experience working with youth with ASD can effectively deliver FYF through use of the manual, although there is evidence that attending a workshop may enhance treatment delivery. Youth across all instructional conditions demonstrated significant reductions in anxiety symptoms, but there was also variability by treatment site. More research is needed to include the development of more refined treatment fidelity measures, strategies to improve treatment response rates in implementation trials, examination of long term follow-up, and inclusion of community clinicians with less experience in working with children who present with either anxiety or ASD. Identifying the “end user” of an intervention at the beginning of any implementation trial can inform workshop content (Drahota, Chlebowski, Stadnick, Baker-Ericzen & Brookman-Frazee, 2017). Adaptations to a given intervention are inevitable during the course of implementation and conversations must occur between researchers and practice sites in order to maximize fidelity. Because FYF is delivered in a group, it may be that the workshop for this intervention should include specific segments on working with youth with ASD in groups; for example, highlighting ways to manage behavioral challenges, provide corrective feedback to parents in the context of a group, as well as to individualize content within the confines of a group modality would be important to emphasize. The relationship between clinician experience and the type of instructional condition required would be important to examine as less experienced clinicians may derive more benefit from Workshop-Plus relative to more experienced clinicians. Results indicated that one of the sites performed less well than the other three sites. Perhaps an in-depth look at treatment outcome by site would yield additional information regarding the impact of training condition.

This study represents an important step in the implementation of evidence-based practice for treatment of anxiety in youth with ASD. By targeting ASD professionals (current study), mental health professionals specializing in anxiety treatments and school personnel (future studies), children with ASD and clinical anxiety who present in a variety of settings may ultimately be able to receive much needed evidence-based interventions.

Public Health Statement.

The purpose of this study is to identify optimal clinician training methods for the delivery of modified group CBT (Facing Your Fears) to children with ASD and anxiety, which may inform and strengthen the interventions’ portability to practice settings.

Acknowledgments

JR is supported in part, by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) under the Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities (LEND) GrantT73MC11044 and by the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AIDD) under the University Center of Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCDEDD) Grant 90DD0632 of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). JR was also supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R33MH089291-03. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by NIH, HRSA, HHS, or the US Government. The authors extend a special thanks to the clinicians, children and parents who participated in this study.

JR was also supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R33MH089291-03.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Judy Reaven, Audrey Blakeley-Smith, and Susan Hepburn receive royalties from the publication of Facing your Fears: Group Therapy for Managing Anxiety in Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders (FYF; Reaven et al. 2011)

Although clinicians were required to work in a clinical setting for youth with ASD, their experience with ASD varied (see Table 1). Experience with CBT was not required in efforts to capture the variety of training experiences of clinicians in the community. One clinician had a Bachelor’s Degree and over 20 years of experience working with youth with ASD so they were included.

These four anxiety diagnoses were the targets of treatment because of the overlap in symptoms between these disorders and because FYF was specifically developed to address these conditions.

Contributor Information

Judy Reaven, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

Eric Moody, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

Laura Klinger, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill.

Amy Keefer, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine/Kennedy Krieger Institute.

Amie Duncan, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Sarah O’Kelley, University of Alabama – Birmingham.

Allison Meyer, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Center.

Susan Hepburn, Colorado State University.

Audrey Blakeley-Smith, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Center.

References

- Bennett-Levy J. Therapist Skills: A Cognitive Model of their Acquisition and Refinement. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;34(1):57–78. doi: 10.1017/S1352465805002420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: a critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Koerner K, Weingardt KR, Kendall PC. Training research: Practical recommendations for maximum impact. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(4):223–237. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0338-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berument SK, Rutter M, Lord C, Pickles A, Bailey A. Autism screening questionnaire: diagnostic validity. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;175(5):444–451. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(10):1230–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee LI, Drahota A, Stadnick N. Training community mental health therapists to deliver a package of evidence-based practice strategies for school-age children with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(8):1651–1661. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0441-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Suveg C, Creed TA, Kendall PC. Involvement shifts, alliance ruptures, and managing engagement over therapy. Elusive Alliance: Treatment Engagement Strategies with High-risk Adolescents. 2010:95–121. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Roy-Byrne PP, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Sherbourne C, Bystritsky A. Treatment for Anxiety Disorders: Efficacy to Effectiveness to Implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(11):931–937. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingfelder HE, Mandell DS. Bridging the research-to-practice gap in autism intervention: An application of diffusion of innovation theory. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41(5):597–609. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1081-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drahota A, Chlebowski C, Stadnick N, Baker-Ericzén M, Brookman-Frazee L. Dissemination and implementation of behavioral treatments for anxiety in ASD. Anxiety in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Evidence-based Assessment and Treatment. 2017;231 [Google Scholar]

- Elkins RM, McHugh RK, Santucci LC, Barlow DH. Improving the transportability of CBT for internalizing disorders in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(2):161–173. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosch EA, Flannery-Schroeder E, Mauro CF, Compton SN. Principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in children. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;20(3):247–262. doi: 10.1891/jcop.20.3.247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W, Bonato RR. Manual for the ECDEU assessment battery. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, National Institute of Mental Health; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, Crocetti E, Raaijmakers QA, Meeus WH. A meta-analysis of the cross-cultural psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):80–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Smith T. Interventions in schools for children with autism spectrum disorder: Methods and recommendations. Autism. 2013;17(3):254–267. doi: 10.1177/1362361312470496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. doi:ARTN 863 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24(5):659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. Second. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Rapee RM. Agreement between telephone and in-person delivery of a structured interview for anxiety disorders in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(3):274–282. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200503000-00012. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200503000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moree BN, Davis TE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: Modification trends. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010;4(3):346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nuro KF, Maccarelli L, Baker SM, Martino S, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. Yale Adherence and Competence Scale (YACS-II) guidelines. Yale University Psychotherapy Development Center. Substance Abuse Center; West Haven: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Olejnik S, Algina J. Generalized eta and omega squared statistics: Measures of effect size for some common research designs. Psychological Methods. 2003;8(4):434–447. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.8.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratto AB, Anthony BJ, Pugliese C, Mendez R, Safer-Lichtenstein J, Dudley KM, Anthony LG. Lessons learned: Engaging culturally diverse families in neurodevelopmental disorders intervention research. Autism. 2017;21(5):622–634. doi: 10.1177/1362361316650394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Beattie TL, Sullivan A, Moody EJ, Stern JA, Smith IM. Improving transportability of a cognitive-behavioral treatment intervention for anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders: Results from a US–Canada collaboration. Autism. 2015;19(2):211–222. doi: 10.1177/1362361313518124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Culhane-Shelburne K, Hepburn S. Group cognitive behavior therapy for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: A randomized trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):410–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven JA, Blakeley-Smith A, Nichols S, Dasari M, Flanigan E, Hepburn S. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for anxiety symptoms in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2009;24(1):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Nichols S, Hepburn S. Facing your fears: Group therapy for managing anxiety in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF, Carroll KM. We don’t train in vain: a dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):106. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Albano A. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for children for DSM-IV: (Child and Parent Versions) San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JA, Gadgil MS, Blakeley-Smith A, Reaven JA, Hepburn SL. Psychometric properties of the SCARED in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014;8(9):1225–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Lewin AB, Collier AB, Arnold E, De Nadai AS, Dane BF, Murphy TK. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety. Depression and Anxiety. 2015;32(3):174–181. doi: 10.1002/da.22332. http://doi.org/10.1002/da.22332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel FJ, Dirksen CD, Bögels SM. A cost of illness study of children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety disorders as compared to clinically anxious and typically developing children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(12):2878–2890. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1835-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel FJA, Bögels SM, Perrin S. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(3):302–317. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainer A, Drahota A, Cohn E, Kerns C, Lerner M, Marro B, Soorya L. Understanding the landscape of psychosocial intervention practices for social, emotional, and behavioral challenges in youth with ASD: A study protocol. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2017;10(3):178–197. [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, Iyengar S. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(26):2753–2766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chu BC, Polo AJ. Treatment Dissemination and Evidence-Based Practice: Strengthening Intervention Through Clinician-Researcher Collaboration. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(3):300–307. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weschler D. Weschler abbreviated scales of intelligence (WASI) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weston L, Hodgekins J, Langdon PE. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy with people who have autistic spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review. 2016;49:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, Oswald D, Johnson C, Southam-Gerow MA, Scahill L. Randomized controlled trial: multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(2):382–394. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, Odom SL, Hume KA, Cox AW, Fettig A, Kucharczyk S, Schultz TR. Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(7):1951–1966. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2351-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Har K, Chiu A, Langer DA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):224–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Klebanoff S, Brookman-Frazee L. Toward the implementation of evidence-based interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorders in schools and community agencies. Behavior therapy. 2015;46(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(3):335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson III tests of cognitive abilities. Riverside Pub; 2001. pp. 371–401. [Google Scholar]

- Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker NJ, Saveliev AA, Smith GM. In: Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Gail M, Krickeberg K, Samet JM, Tsiatis A, Wong W, editors. New York, NY: Spring Science and Business Media; 2009. [Google Scholar]