Abstract

Although randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCT) are critical to establish efficacy of vaccines at the time of licensure, important remaining questions about vaccine effectiveness (VE)—used here to include individual-level measures and population-wide impact of vaccine programmes—can only be answered once the vaccine is in use, from observational studies. However, such studies are inherently at risk for bias. Using a causal framework and illustrating with examples, we review newer approaches to detecting and avoiding confounding and selection bias in three major classes of observational study design: cohort, case-control and ecological studies. Studies of influenza VE, especially in seniors, are an excellent demonstration of the challenges of detecting and reducing such bias, and so we use influenza VE as a running example. We take a fresh look at the time-trend studies often dismissed as ‘ecological’. Such designs are the only observational study design that can measure the overall effect of a vaccination programme [indirect (herd) as well as direct effects], and are in fact already an important part of the evidence base for several vaccines currently in use. Despite the great strides towards more robust observational study designs, challenges lie ahead for evaluating best practices for achieving robust unbiased results from observational studies. This is critical for evaluation of national and global vaccine programme effectiveness.

Keywords: observational studies, case-control studies, epidemiologic methods, test-negative design, negative control, ecological study

Key Messages

Observational studies are a key part of the evidence base for the effects of vaccines (vaccine effectiveness, VE), especially at the population level and for rare but severe outcomes of infection, such as death. Yet these study designs suffer from the risk of bias due to confounding and other factors.

Using the illustrative example of influenza vaccines, we show that such biases can be large and describe three strategies—the use of negative control outcomes, the use of the test-negative design, and the use of time-trend studies—to detect and reduce various forms of bias in observational studies.

Each of these strategies can be very effective but each depends on certain assumptions for validity, and each may introduce new forms of bias into the analysis.

Further work is needed to develop best practices for observational VE studies in the post-licensure period, possibly relying on a combination of designs that may have different forms of bias.

Introduction

Although vaccine licensure requires evidence of vaccine safety and efficacy from randomized controlled trials (RCT), many questions about vaccine effectiveness (VE) can be answered only by observational approaches after the vaccine is in use. For example, the effects of a vaccine on a rare outcome, such as mortality, can typically be studied only through observational approaches. Even within an RCT, the effects of a vaccine on a subgroup defined after randomization (and therefore not protected by randomization against confounding and selection bias) may be of interest; such subgroup analyses are observational, despite being nested within an RCT. Once a vaccine is licensed and recommended for use, certain RCTs may face ethical challenges,1 though there may remain VE questions of interest. Finally, RCTs randomized at the individual level are designed to measure only the direct protection the vaccine offers to vaccinated persons, but not the important overall effect of vaccination on disease in the population, including that achieved by indirect protection of unvaccinated people (herd immunity). Post-licensure observational studies—specifically ecological time-trend studies comparing population-level disease burdens in the pre- and post vaccination period—are well suited to measuring indirect and overall effects.2–4 Such studies deliberately measure a different quantity from that measured by individual-level studies of VE, but it is one that is highly relevant to policy making.

VE may be studied using any of the three major classes of observational study design: cohort, case-control and ecological studies. Such observational VE assessments are subject to the effects of confounding and other forms of bias. In particular, those who do and do not receive a vaccine may differ in ways that affect the chance of experiencing the outcome (e.g. mortality or infection). If so, these differences confound the measured effect of the vaccine on the outcome. In this paper, we describe approaches to identify, address and reduce the impact of such confounding in observational VE studies. We provide examples of each approach as well as a formal account, using causal directed acyclic graphs, of how each approach attempts to address this source of bias and what assumptions are required for it to be a valid approach.

Specifically, we use a causal framework to describe the typical problem of confounding in VE studies and describe three approaches that have been used to address the problem: (i) the use of negative-control outcomes in a cohort or case-control study; (ii) the use of a laboratory test-negative-control group in a study of all patients tested for the infection of interest; and (iii) the use of an ecological time-trend design to measure indirect and overall causal effects.5 Our running example is the problem of estimating influenza VE, a recently controversial area that illustrates how concerns about bias in the evidence base arose, how these approaches to reduce or detect bias are used and how well they address the issues we are raising. Influenza VE studies raise nearly all the types and issues of potential bias, and all the strategies we discuss have been recently applied. Whereas we use influenza VE as an example, we make occasional reference to other vaccines for which these strategies have been deployed. Box 1 lists some of the key substantive insights for multiple vaccines that have been gained from the strategies we discuss.

Box 1. Substantive insights from published literature using the three approaches described in this paper

Substantive insights from negative-control approaches

Showed that the vaccine-preventable burden of influenza mortality has been overestimated due to confounding.6,14,15

Added confidence to several studies of cholera VE in outbreaks by showing that VE was estimated to be not statistically different from zero for non-cholera diarrhoea.65–67

Substantive insights from test-negative designs

Measured and compared VE of pandemic and seasonal vaccines in various seasons, documenting variation across seasons and sometimes across vaccines within a season, in studies where classical controls were not employed.45,72,73

In a few studies where different control groups were compared, VE estimates were sometimes similar for the test-negative design74 and sometimes different;75 a comparison of per-protocol results from RCTs versus estimates from test-negative observational studies of an influenza vaccine and of a respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) monoclonal antibody showed close concordance.26

Found that protection appears to decline over the course of influenza season, either due to waning immunity or changing composition of the at-risk group.38–40

Complemented other study designs to produce a consistent finding that the 2008–09 seasonal influenza vaccine increased the risk of laboratory-confirmed clinical infection with 2009 pandemic flu.17

Confirmed traditional case-control findings of high VE for monovalent and pentavalent rotavirus vaccines in children.76–79

Confirmed traditional case-control findings of likely waning immunity after the fifth dose of pertussis vaccine in children, with results similar to those found with traditional controls.80

Suggested that classical case-control design overestimates VE of reduced acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccines in adolescents and adults.81

Confirmed traditional case-control or RCT findings of high VE for pneumococcal vaccines.28,29,82

Detected low measles VE among children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.83

Substantive insights from ecological designs

Showed that the vaccine-preventable burden of influenza mortality has been overestimated due to confounding.15

Showed that conjugate vaccines against Hib and pneumococcal disease have large direct and indirect effects on invasive disease hospitalizations.2,3,84

Showed reduced benefits due to serotype replacement which led to shift from PCV7 to PCV13.69

Demonstrated effect of rotavirus against paediatric diarrhoea mortality in Mexico.4

The General Problem

In observational VE studies that compare outcomes in vaccinated vs unvaccinated persons, these groups may differ in ways that affect their risk of infection or death, for reasons other than their vaccination status. For example, those who get vaccinated may have better access to health care for geographical, financial or other reasons; may be more inclined to seek health care; or may have access to different quality of care, for example more preventive health care services. Moreover, vaccinated persons may simply tend to be healthier with high ‘functional status’, allowing them to physically be able to get to an influenza vaccine appointment.6 Each of these characteristics may be predictive of the outcome measured in such studies, which may be laboratory-confirmed infection, illness or mortality (cause-specific or all-cause). If not adequately measured and adjusted for in analyses, these differences may confound the association between vaccine receipt and the outcome, biasing estimates of VE.

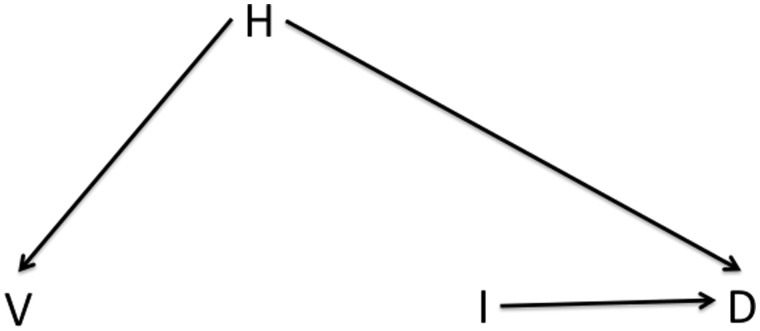

This issue is shown in Figure 1, a causal directed acyclic graph (DAG)7 showing the causal connections among vaccination (V), laboratory-confirmed infection (I), death (D) and various confounders (H, health care access or health status). Directed arrows connecting these nodes indicate that there is assumed to be a direct effect of one variable on another. The absence of such an arrow means that there is assumed to be no direct effect of one variable on another. By convention, no arrow is shown for the causal effect that the study is attempting to estimate, here the effect of vaccination on infection or death. Confounders of these relationships are those variables that affect whether an individual becomes vaccinated (the exposure of interest) and also, separate from the vaccine effect, whether the individual becomes infected or dies (the outcomes of interest). We wish to identify the causal effect of the vaccine on infection or death, and to estimate these effects from the observed associations between V and outcomes I or D. To do so, we must account for potential confounding by H. For a detailed introduction to how to read such diagrams, see reference 8.

Figure 1.

Causal structure of observational VE studies showing the possible confounding of the vaccine (V)-outcome (e.g. hospitalization or death D) relationship by health status, health-seeking behaviour or other characteristics that may differ between those who do and do not receive vaccination. Any causal effect of vaccination on D must be mediated by I, infection with the pathogen against which the vaccine protects.

Three Approaches to Address Bias in Observational ve Studies

Use of negative controls to detect confounding in studies of VE against mortality and other severe outcomes

Identifying evidence of profound bias in cohort studies of influenza VE

Influenza vaccines were developed in the 1940s for use in military populations and have, since the 1960s, been used mostly to vaccinate the elderly despite early concerns that immunosenescence may attenuate their effectiveness in old age.9 Once influenza vaccines were licensed and recommended for the elderly, it became ethically difficult to use a placebo-controlled randomized trial design to evaluate VE in this age group. Therefore, nearly all VE studies in the elderly have been observational, using International Classification of Disease coded diagnoses in electronic health maintenance organization (HMO) databases (for an exception see ref. 10). These studies had consistently reported astonishing vaccine benefits—that influenza vaccination in the elderly prevents as many as 50% of all deaths during winter.11–13 A decade ago, concerns arose that this assessment far exceeded what reasonably could be expected6,14,15 and might reflect uncontrolled confounding.

Any causal effect of influenza vaccination on mortality should be evident only during influenza epidemic periods, usually in midwinter. Thus, any mortality advantage among vaccinees occurring in the immediate pre-epidemic months would indicate bias, likely due to confounding.6,16 To test for the existence of bias, Jackson et al. first reproduced in HMO data the original finding of 50% winter all-cause mortality reduction, then went on to stratify the measurements according to timing (before, during and after influenza). They found that the largest reduction occurred in the pre-influenza period and concluded that such studies had likely greatly exaggerated the true vaccine effect. Later studies showed that this confounding was particularly severe in studies of all-cause mortality but less of a problem when studying more specific outcome, such as hospitalization or mortality from pneumonia.

Testing for an effect of vaccination on an outcome that could not plausibly be affected by the vaccine is an example of a more general strategy that has been called the ‘negative-control outcome’ strategy. Though initially controversial, this bias-detection approach is now commonly used in studies of influenza VE.14,17–21 Recent observational studies also use more specific endpoints (e.g. pneumonia hospitalizations instead of all-cause mortality) for which VE can be more reliably estimated. The newer studies demonstrated that the VE against these endpoints was in fact low in seniors, helping to stimulate the development of more immunogenic vaccines for the elderly.19

A causal account of the use of negative-control outcomes to detect bias

This finding inspired formal research on the use of this strategy for bias detection in epidemiological studies more generally. This approach has been termed a ‘negative-control outcome’ analysis, by analogy to laboratory experiments in which researchers include ‘negative controls’ to verify that the experimental system shows no effect when it should not.22

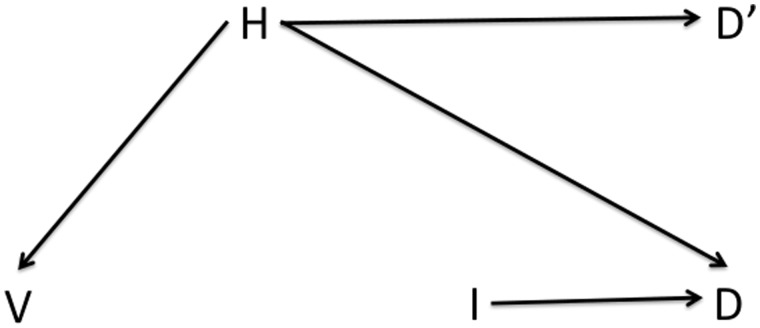

Figure 2 shows a modified DAG similar to that in Figure 1, but now including a negative-control outcome, death before the influenza epidemic period (D’). By assumption, vaccination (V) has no causal effect on death outside the influenza season, but the common causes of V and D (that is, the confounders of the V- > D relationship) should also be causes of D’. In other words, any association between V and D’ should reflect pure confounding, in the absence of any causal pathway from V to D. Applying an analytical strategy to D’ (e.g. performing a regression of the mortality outcome D’ with a particular set of exposures, focusing on the estimate of the coefficient for V), and finding a significant protective effect of V, indicates that the same strategy applied to an outcome D is likely to provide a biased estimate of the causal effect of V on D. Moreover, under certain assumptions the direction of bias should be the same for the outcome of interest (D) as for the negative control (D’): in this case, the measured VE against death should be biased upwards.22

Figure 2.

As Figure 1, but showing a negative-control outcome D’ (for example death outside influenza season) that has no causal connection to vaccination but shares the same confounding relationship with H as the outcome of interest D.

The assumptions underlying the valid use of a negative-control outcome are: (i) that the exposure does not have a causal effect on the negative-control outcome, either directly or indirectly; and (ii) that all confounders of the exposure-outcome relationship have the same causal effect on the negative-control outcome as they have on the outcome. Assumption 1 may be satisfied if the influenza epidemic period is accurately characterized and if influenza vaccination has no effect, directly or indirectly, on mortality that is not caused by influenza infection. Both of these are plausible premises (non-specific effects of some vaccines on deaths not caused by the pathogen in the vaccine have been reported,23 though not to our knowledge for influenza vaccine). Assumption 2 is reasonable in the temperate regions if those factors that predict whether an individual gets vaccinated in say, early autumn, are equally predictive of mortality before influenza season as during influenza season.

The use of negative controls to detect the existence and direction of bias has several advantages. Under the assumptions above, negative control outcomes can detect confounding and other forms of bias, even if the investigator has not identified the likely source of the bias ahead of time. Similarly, if one has identified a potential confounder of the relationship of interest and wants to know whether it has been adequately controlled in an analysis, the analysis can be applied to a negative control outcome to find out. Indeed, Jackson et al. did just that to test the adequacy of ‘standard’ statistical approaches (multiple regression modelling) to controlling for health status in the elderly, and found that those had in fact been counterproductive and had exacerbated the overestimate of VE.6

The principal limitation of the negative-control outcome approach is that it does not offer a straightforward formula to correct for these biases. It can urge caution but cannot solve the problem it identifies. However, identifying the bias may be a first step toward refining the analysis to reduce it; these refined analyses may then be submitted to negative-control analyses to see if the problem has been resolved. Work is under way to expand the idea of negative controls to correct for, rather than just detect, biases.24,25

Test-negative designs

Confounding in studies of VE against clinically apparent infection

To assess VE against clinically attended infection, investigators often choose the case-control design for its ability to give results rapidly and with moderate sample sizes. As in other observational designs, vaccinated and unvaccinated persons may differ in systematic ways that may lead to confounding of the vaccine’s effect. An increasingly popular, convenient and cost-saving approach to such VE studies is the use of a ‘test-negative’ control group. ‘Cases’ in such studies are individuals with a defined clinical syndrome who test positive for the pathogen for which the vaccine is designed, and ‘test-negative’ controls are those with the same clinical syndrome who had tested negative.1 This novel approach goes by different names and is sometimes seen as a variant of the case-control approach.26 Because it differs from a case-control study in that participants are ascertained prior to knowledge of their outcome, without a fixed ratio of outcomes in the study27 it could be seen as a type of cohort study; indeed, arguably the first test-negative vaccine study was called an ‘indirect cohort’ study.28 To avoid semantic confusion we simply call it the test-negative design. The motivating idea for the design is that, if a major source of confounding in the vaccination-disease relationship is a differential tendency to seek health care when ill between those who get vaccinated and those who do not, then limiting the analysis to those who have sought health care for a similar illness should reduce or eliminate this source of confounding.

It has over past decades become established practice in the USA, Canada and Europe to base influenza VE estimates on such test-negative studies conducted during and immediately after each influenza season. The ‘cases’ and ‘test-negative controls’ both sought care for an influenza-like illness, typically defined as fever plus respiratory symptoms,17,26,29–31 and the test-negative controls are those who test negative on the real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing for influenza virus.

A causal account of the test-negative design

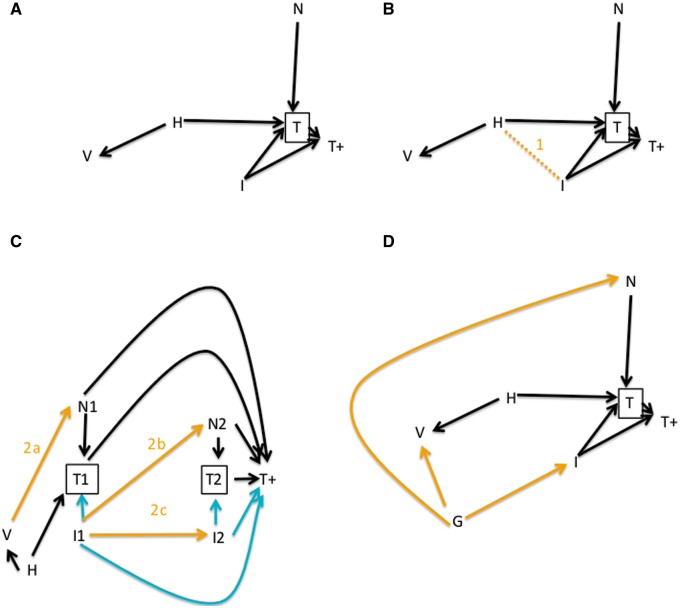

The use of test-negative controls means that we are not studying the relationship between vaccine (V in Figure 3A) and influenza infection (I), but the relationship between vaccine and testing positive for influenza (T+) among those who are tested (T). In our expanded causal diagram for this design, we also include other factors that affect whether an individual gets tested for influenza (N), such as other infections. Figure 3A illustrates that by conditioning on testing, we block the confounding effect of healthcare-seeking behaviour (H, whether measured or not) on the vaccination-influenza-positive relationship. In the language of causal DAGs, we block the back-door path between vaccination and the outcome V ← H → T → T+.

Figure 3.

Causal diagrams of the test-negative design. Here, the outcome of interest is laboratory-confirmed clinically attended influenza infection (T+). A: As before, health-seeking behaviur or other characteristics H may differ between those who do and do not receive vaccination, and may affect the probability of receiving a test for influenza (T) through other confounding pathways (H- > T). The test-negative design conditions on T by including only those who are tested, and thereby blocks this confounding effect. B: However, this conditioning creates selection bias, a non-causal association (orange line 1) between health-seeking behaviour and infection, by conditioning on their common effect, biasing the V- > T+ association. C: The test-negative design in greater detail, including two time periods (e.g. consecutive weeks) in which individuals are enrolled. The study is intended to measure protection by the pathways shown in green. Bias may occur if (arrow 2a) vaccination has a short-term, non-specific effect on other infections N, or (arrow 2b) if influenza is temporarily protective against other infections N or (arrow 2c) if influenza is protective against influenza later in the season. D: The test-negative design does not protect (nor does the ‘classic’ case-control design) against confounding effects in which some factor G (e.g. being a health-care worker) is a common cause of both getting vaccinated and getting infected, given vaccination status.

The advantage of avoiding this form of confounding is balanced by several disadvantages, which can also be understood in the context of a causal diagram and are shown by the numbered arrows in Figure 3B-D. We have added further arrows (shaded orange for clarity), each representing one of the concerns described below.

Concern 1

Selection bias introduced by limiting consideration to those tested. Both influenza infection and health care-seeking behaviour, by assumption, influence the probability of being tested for influenza. The use of test-negative controls is equivalent to conditioning the analysis on testing, which is a common consequence of both health-seeking behaviour and influenza infection. This induces a correlation among the tested persons between their health-seeking behaviour and influenza positivity, which induces selection bias in the estimate of VE.32 This form of selection bias or ‘collider bias’, correlation between the two causes of a common effect when conditioning on that common effect, is shown as a dashed line (Line 1, Figure 3B).

Concern 2

Bias due to measurement of effects other than those directly through preventing influenza. The scientific goal of VE studies is to measure the direct effect of influenza vaccination on preventing clinically attended, laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. If the vaccine has other effects that can mimic or mask this direct effect, then the effect will be overestimated or underestimated, respectively.

Figure 3C illustrates these biases, expanding Figure 3A to show that VE studies take place over time—in the case of influenza VE studies, usually over a full season. For simplicity we show only two time points, 1 and 2, which might be consecutive weeks during the season. The arrows shown in cyan indicate the pathways through which the test-negative design is meant to estimate VE, through the effect on preventing influenza infection. If a person is less likely to become influenza-infected, s/he is less likely to seek testing and less likely, if tested, to test positive for influenza. The orange arrows show three pathways by which this effect could be biased.

The first such potential source of bias occurs if the seasonal influenza vaccine has an effect (for example protective) on non-influenza conditions that present with influenza-like symptoms. In this case, vaccination could cause someone to be less likely to be a control than a typical member of the general population (arrow 2a). Typically, it is assumed that this cannot happen because influenza vaccines confer antigen-specific immunity that should be protective only against influenza. Yet at least some influenza vaccines induce innate, non-specific antiviral immune responses33 that could reduce the risk of other viral infections for a short period of time after immunization, possibly an example of a more general phenomenon.34 Graphically, this corresponds to a pathway by which vaccination increases the probability of testing positive among those tested, not via any effect on influenza but by reducing the frequency of other conditions that, to testing, V → N → T+. If this occurs, the test-negative design will be biased to show less protective effect against influenza because some of the benefit is hidden by protection against other infections.

The second such potential source of bias occurs if influenza infection itself induces non-specific protection against later acquiring non-influenza infections (arrow 2b). In this case, the vaccine’s protection against influenza in any given week could increase the risk of non-influenza respiratory infection, and hence of being a test-negative participant, in a subsequent week (arrow 2b). There is some evidence for such an effect.35 This bias will occur only if there is a true benefit of influenza vaccine against influenza infection, but will lead to an overestimate of this protection because vaccinated individuals will be less likely to appear in the control group than in the general population. Graphically, if the vaccine has some effectiveness against influenza infection, there will be a path V → I1 → N2 → T+ that includes an effect the study is not designed to measure.

The third such potential source of bias occurs because people who get influenza once in a season are usually immune to getting it again that season36 (arrow 2c). Therefore as the influenza season progresses, if the vaccine is effective, persons at high risk of influenza infection will be removed more rapidly from the unvaccinated than the vaccinated group, and the apparent effectiveness will decline over the course of the season.37 Thus the within-season immunity will attenuate VE estimates over the course of the season, if the vaccine is effective. This appears to have happened in the 2012–13 influenza season in the USA, where VE estimates declined over the course of the season.38–40 This source of bias, unlike the previous two, occurs even with an ‘ordinary’ case-control design, as it does not depend on the choice of controls but rather on the fact that influenza is an immunizing infection. The graphical representation of this bias is the path V → I1 → I2 → T+.

Concern 3

Residual healthy vaccinee effects. The use of test-negative controls will eliminate confounding that arises because vaccinated, influenza-infected people have a different probability of getting tested compared with unvaccinated, influenza-infected people—for example because they are greater users of health care services. However, those who get 0vaccinated may also be more likely to get influenza than those who do not, for example because of their age or geography. We indicate such confounding with a new factor G in Figure 3D, which plausibly affects risk of both influenza and other infections. If these other factors are not separately controlled for, the use of test-negative controls will not remove their confounding effects. This problem arises whether conventional controls or test-negative controls are used, so is not unique to the test-negative design; we mention it merely to highlight that it is not solved by the test-negative design.

Concern 4

Misclassification of false-negative cases as controls. Use of any diagnostic test for the identification of cases and controls has the potential of misclassification. Imperfect sensitivity of the diagnostic test leads to false negatives, so that some who should have been cases become controls. Imperfect diagnostic test specificity allows true influenza-negative individuals to become misclassified as cases. Either form of measurement error may lead to attenuation of VE estimates. A recent simulation study, however, indicates that with realistic values of VE and currently available influenza tests, the magnitude of this bias is negligible.41

Notwithstanding the possibility of all of these forms of bias, test-negative studies have reported plausible results, including very low or no effectiveness of severely mismatched vaccine formulations for certain seasons such as 2014–1542–44 and for elderly in multiple seasons.30,40 The test-negative study design was used in a study that argued that receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine was associated with increased risk of H1N1pdm morbidity during the 2009 pandemic period in Canada.17 It was also used to demonstrate that live attenuated vaccine was less effective than TIV(IIV: inactivated influenza vaccine) in adults45 and children.46 Finally, IMOVE, a large multi-country European study, routinely uses the test-negative approach to produce one pooled influenza VE estimate during each season across Europe.47

Time-trend VE studies

Time-trend study designs offer another approach to avoid some forms of confounding in VE studies. These studies, which are ecological in design, do not compare the incidence of infection or other outcomes in vaccinated vs unvaccinated persons, so they are not subject to the kinds of confounding by health status or health-seeking behaviour described in the previous sections. Instead, they estimate the reduction in an outcome following vaccine introduction in a population, where the outcome is measured in individuals (who either die or survive) but summed over the whole population. Thus, such studies estimate the effect of a change in the proportion vaccinated in a population on the frequency of that outcome in the population—a causal quantity of policy relevance. Such studies have been widely used to demonstrate and quantify the effect of vaccines including pneumococcal conjugate vaccines,2,29,48,49Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines3, influenza vaccines15,50 and rotavirus vaccine.51

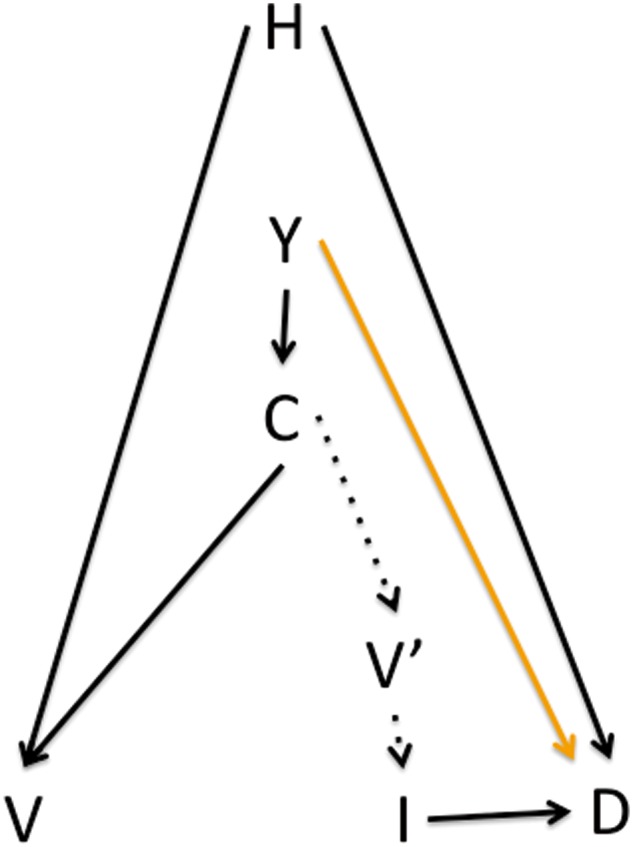

Time-trend VE studies aim to measure a different quantity from the VE that is estimated in individual-level studies such as cohort and case-control studies. The impact of changing coverage of a vaccine in a population is of considerable interest to policy makers, who would like to know the number of cases that would be prevented under a vaccination programme targeting a particular segment of the population. Among observational designs, an ecological study is uniquely appropriate to measure exactly this quantity. For contagious diseases, the impact of vaccinating a substantial segment of the population will be a combination of the protection to vaccinees and indirect (‘herd immunity’) protection for those who are not immunized. Here the terms direct and indirect are used in their infectious disease sense, which differs from that typical in the causal inference literature.52. In infectious diseases we use indirect protection to refer to the phenomenon that preventing infection in the vaccinated members of the population reduces infection risk to those who are unvaccinated.53 In Figure 4, we provide a modified causal diagram that includes the same elements as Figure 1, with the addition of year (Y) and vaccine coverage (C). We do not consider more than 1 year, reflecting the assumption that vaccination and infection dynamics in 1 year do not affect those in future years. This is a simplification but a commonly made one for influenza; relaxing this assumption would involve complexity beyond our scope. We show the hypothesized routes of vaccine coverage effect on infection: direct effects on the vaccinees (C → V → I) and indirect effects through the vaccine status of other members of the community on the infection risk of an individual (C → V’ → I). Often the outcome measured is mortality or hospitalization (D).

Figure 4.

In a time-trend study of vaccine effects, year (Y) affects vaccine coverage C, which can be interpreted as each individual’s risk of being vaccinated V. Coverage also affects the vaccination status of contacts V’, which affects (through herd immunity) an individual’s infection risk. The association between coverage and the outcome D (typically a severe one, such as pneumonia or death) will be causal if year is affecting the outcome only through vaccine coverage and not through other paths such as development—that is, if the orange arrow is absent.

By estimating the causal effect of coverage on the total number of outcomes of interest (for example, pneumonia deaths when focusing on influenza vaccine), a time-trend study circumvents the confounding by individual health-seeking behaviours H that affects other study designs; H is by assumption not a confounder of the relationship between coverage (which can be interpreted as the average probability of vaccination in the population) and the outcome.

Time-trend studies may be used to study the overall effect of vaccination, that is the reduction in average risk for a person in a vaccinated population with a given level of coverage, compared with a person in an unvaccinated population.54,55 Moreover, it may be limited to age groups that are not eligible for vaccination, studying the indirect effect of the vaccine, which is the impact of increased vaccine coverage in one age group on outcomes in another.3 This approach has also been used to study the indirect (herd immunity) benefits of infant pneumococcal conjugate vaccine PCV vaccine use as a way to protect adults.29,49,55,56

For influenza, researchers in several countries used a time-trend study to estimate the reduction in pneumonia and influenza mortality in the elderly over a few decades, as vaccination coverage in this age group increased from marginal to over 65%—but failed to see any downward trends.15,57 It was these studies that led to a re-examination of the evidence base from other observational studies that had reported astonishing mortality benefits.14 Ultimately all of these efforts led to the understanding that more immunogenic vaccine formulations may be needed for seniors, and the renewed interest in pursuing strategies for influenza control, such as the vaccination of ‘transmitters’ including children to achieve herd protection of elderly.58

Conditions for the validity of time-trend VE studies

Ecological study designs have been justifiably criticized when the question of interest is how a particular exposure, such as vaccination, affects an individual’s risk of an outcome, such as death. The term ‘ecological fallacy’ is used to describe the problem with ecological studies that aim to estimate such individual-level quantities. However, this line of criticism does not apply to ecological VE studies, properly interpreted, because they do not aim to make inferences about individual vaccination and individual risk, but rather about the impact of changing vaccine coverage on the risk of a group of people.

Thus an ecological study comparing outcomes in populations with different levels of coverage may be considered as the non-randomized analogue of a cluster-randomized trial. An ecological VE study may compare incidence within a single population in different years where vaccination coverage was different, or across different populations with different levels of coverage. In this respect, an ecological study design is the proper observational study design to estimate overall vaccine effects. Like other observational studies, this design may suffer from confounding when populations that have different levels of vaccine coverage also differ in incidence of the outcome for reasons separate from the level of vaccine coverage. These confounding factors may include the ag -distribution of the population, economy/development (which may influence both vaccine coverage and risk of severe outcomes of an illness), the recent incidence of the disease in the population (which might affect the prevalence of natural immunity to the disease) or the extent of co-circulation of other agents that can affect the outcome (for example, bacterial infections that can lead to complications of influenza infection). Such factors may confound estimates of VE, because they imply that year (in our example) has an effect on the outcome through some variable other than vaccine coverage (there may be an arrow from Y directly to D). In such a situation, it may be possible anticipate the direction of the bias induced by such confounding, or even to measure and adjust for it; for example, population ageing or comparison of communities with different age structures could be improved by using age-standardized mortality rather than crude mortality.15 Likewise, adjusting for the expected reduction in severe infection outcomes as a result of socioeconomic development is needed when studies are set in lower- and middle-income countries.59 Practically, if baseline data on the outcome are available for a period before the vaccine is introduced, evidence of a trend prior to vaccine introduction could be accounted for analytically, though there is no guarantee that extrapolating the pre-vaccine trend will accurately capture what would have happened without the vaccine.

These considerations also urge caution about the external validity of a time-trend study of VE. The proportion of a non-specific outcome preventable with a particular vaccine will depend on the mix of causes of that outcome. For example, a vaccine against any individual pathogen that causes pneumonia will likely prevent a changing proportion of childhood pneumonia deaths as a population goes through epidemiological transition and profoundly lower background childhood mortality.59

An important consideration of time-trend VE studies is that the disease or mortality outcome under study must be sufficiently specific so that the vaccine’s impact on it is likely to be measurable. For most vaccines, all-cause mortality is so non-specific that the true causal effect of an effective vaccine would be expected to be only marginal, making a true effect hard to discern. Moreover, should other non-vaccine changes occur they are more likely to cause confounding, resulting in misattribution to the vaccine of other causal factors affecting general mortality.

Discussion

Global vaccine efforts continue to expand thanks to the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI)60 and the continuous arrival of new vaccines (rotavirus, human papilloma virus, PCV and others). Given the need for ongoing evaluation of VE of all these vaccines as they are introduced in new geographical areas and in new population segments, exclusive reliance on evidence from randomized trials is impractical for ethical, logistical and economic reasons, and is unsatisfactory because severe outcomes of most interest for policy purposes are rarely studied. Therefore the evidence base is typically built on post-introduction (phase IV) observational studies, studies characterized by a risk of bias due to confounding when differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated persons are not adequately measured and adjusted for. Many such observational studies are performed each year, but there has been no systematic assessment of the conditions under which particular study designs are to be preferred, or how disparate results should be compared. Toward that end, we have presented an overview of three of the most important approaches to improving the reliability of observational studies for estimating VE. Using the framework of causal inference and the tool of causal DAGs, we have identified conditions under which each of these study designs is valid, and thereby conditions under which they may be biased. Importantly, the existence of a possible bias does not imply that this bias will be large relative to the effect being estimated. As a corollary, the number of potential biases identified for a particular design is not an indicator of the design’s desirability, as these biases may be of trivial magnitude in particular cases. Some work has been done, but more work is needed, to estimate the likely magnitude of these biases.- Such work is important because of the high reliance on such studies to provide the evidence base used to set vaccine policy.

Failure to account for such biases has led to large errors in the estimates of vaccine effects in observational studies, and that these errors may be amplified as they gain authority and apparent precision through the process of systematic review and meta-analysis. A now well-established example of this comes from influenza VE literature, in which most of the published observational studies up to 2005 or so were afflicted with unadjusted confounding that had led to profound overestimation of vaccine benefits in seniors.14 That flawed evidence base had suggested that one death could be saved by vaccinating 150–300 elderly persons—when in fact seniors respond poorly to influenza vaccine. Once the cohort study designs had been improved and bias detection strategies incorporated,17,18,62 earlier reports of astonishing mortality savings were replaced with the insight that these studies suffered from confounding that led to dramatic VE overestimation. This finding was reinforced by evidence from a trend study of modest effects at the population level.15 We have discussed three approaches to avoiding or circumventing such bias in observational studies—but each involves trade-offs. Characteristics of the three approaches are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Newer observational study designs and strategies used to measure VE and identify and reduce bias

| Strategy | Applicability to types of studies | Summary | Attractive feature | Example of study that used this approach | Conditions for validity | Trade-offs/limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative-control outcome | Case-control, cohort, ecological | Apply parallel analysis to an outcome that should not be affected by vaccine to detect bias in VE estimation | Improves confidence in validity of analytical approach | Ref. 19 | Negative-control outcome must share confounders of the outcome of interest, but be causally unlinked to vaccine | Can detect direction of bias under some assumptions, but can rarely correct for it |

| Test-negative case-control | Often seen as a form of case-control study but26 may be better understood as a form of cohort study | Choose those who have been tested for clinical syndrome of interest but test negative for target pathogen as controls, to avoid confounding affecting propensity to get tested | Easy, inexpensive access to control group in a surveillance setting | Refs 17, 28, 76–79, 83 | (i) Vaccine must not affect probability of conditions that lead to testing negative (e.g. other infections) either directly or indirectly (ii) Test highly sensitive and specific | (i) Creates selection bias by conditioning on testing, leading to non-causal associations among those tested between vaccination and infection. (ii) Does not eliminate confounding due to vaccinees having different risk of infection from non-vaccinees, e.g. due to place of residence or occupation |

| Ecological or trends study | Ecological study | Compare outcome over time or across populations with varying vaccine coverage to avoid assumption that vaccinated and unvaccinated are comparable | Allows study of total effect of vaccine on population [direct + indirect (herd) effects] | Refs 4,15,29,49,55,56,57 | Any causes of time trends in the outcome other than vaccination must be identified and adjusted for, or extrapolated from time trends before the vaccine is introduced | Major concern is ability to adjust for non-vaccine time trends. Variability in epidemiological context makes extrapolation of indirect/total effects questionable |

First, the use of negative controls in an observational study can be a powerful way to detect bias, but only if the relationship between confounders and the negative control outcome closely resembles the relationship with the outcome of interest, and if there are no other sources of association between vaccination and the negative-control outcome. The use of pre-influenza mortality as a negative-control outcome is particularly suitable because there is strong biological plausibility to these assumptions, but in other situations (in particular for non-seasonal diseases) the available negative-control outcomes may be more open to question. Further efforts are needed to define operationally how negative-control outcomes can best be selected. Meanwhile, we can perhaps think of the negative-control outcomes as ‘sensibility analyses’; more than typical sensitivity analyses, these are meant to add biological meaning to the exploration of robustness of the VE findings.

Second, the test-negative approach is now widely used to provide timely and accurate VE estimates from laboratory-based surveillance data. The upside of test-negative studies is that they can eliminate important confounding effects of health-seeking behaviour, but the downside is that they do so at the cost of risk of selection bias that leads to a non-causal association between health-care-seeking behaviour and infection with the pathogen of interest. Moreover, this design requires that neither the infection of interest, nor the vaccine of interest, affects the probability of other infections that may lead someone to be a test-negative control. These assumptions are questionable in many circumstances, though the evidence is limited for most infections. We suspect that the downsides of the test-negative approach will often be outweighed by the advantages of avoiding confounding by health-care-seeking behaviour, but additional simulation studies may help to throw light on the magnitude of potential biases. Meanwhile, it will often be possible to include both test-negative controls and other control groups that have different properties. Consistent results from such comparisons will be reassuring.

Third, time-trend studies are often used to demonstrate benefits of vaccine programmes. The advantages are that these are by design free of confounding due to individual differences by studying rates in the whole population, and uniquely address the important question of the overall population-level effect of vaccine coverage (different from case-control and cohort studies that can only measure the direct VE). The main disadvantage is that these studies are prone to their own forms of confounding, if other factors besides vaccine coverage that affect the outcome are changing over time along with vaccine coverage. Such confounding, if measured, may be demonstrated by the use of negative-control outcomes, and adjusted for in various ways. Despite being somewhat unfairly stigmatized for being ‘ecological’, this class of studies is appropriately prominent in the evidence base because of the importance of measuring population-level effects, especially on outcomes that are too rare to measure in most RCTs.

The approaches to address bias in observational studies described here can be combined or blended. For example, time-trend studies were used to investigate the impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on respiratory hospitalizations, and investigators used various negative-control outcomes, such as dehydration64 and urinary tract infection49 hospitalizations, to rule out other population-level trends that could have affected hospitalization rates in general.

In another example, several VE case-control studies for cholera vaccines have used confirmed cholera diarrhoea as cases and chose as controls persons who did not seek treatment for diarrhoea—a conventional design.65–67 They then did a parallel ‘bias-indicator’ analysis using those who sought treatment for diarrhoea but did not test positive for cholera as cases and conventional controls, showing that the study design did not find measurable VE for a non-cholera outcome. This negative-control outcome approach has an obvious similarity to the test-negative design.

Considering the importance given to positive evidence from trends studies4,49,64,68,69 in shaping vaccine policy, and given that the time-trend study design is the only one to capture the overall benefits of a vaccine programme, it is critical that much effort goes into the identification of strategies for bias detection and bias elimination and to the validation of findings and elimination of any other explanation than vaccine for observed reductions in an outcome. Unfortunately, the literature at this point is not coordinated with respect to bias detection and trends adjustment strategies. Furthermore, more effort is needed to assess the extent of bias favouring publication of papers with expected or positive results.

We have not comprehensively drawn attention to every source of bias in each of the three approaches considered here, but have concentrated on those that are particular either to the design itself or to the class of VE studies. These different kinds of study design approaches have different strengths and limitations, such that consistency of evidence from more than one of these may be more compelling than repeated, consistent findings from one study design.17 This may suggest that instead of the classical ‘hierarchy of evidence quality’, the strength of evidence on a question should be evaluated by the consistency of findings across study designs.70,71

In conclusion, challenges lie ahead for evaluating best practices for achieving robust unbiased results from observational VE studies. Short of enormous cluster-randomized trials at the time of introduction of a new vaccine, these will form the major part of the evidence base used to evaluate national and global vaccine programme effectiveness. Great strides have been made in recent years, but this is an unfinished agenda.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Hernan for helpful discussions.

Funding

ML's work was supported by Award Number U54GM088558 from the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. LS acknowledges a Marie Curie Actions Individual Fellowship from the European Commission and a grant from the Lundbeck Foundation, Denmark.

Conflict of interest: M.L. has received research funding through his institution for vaccine modelling studies from Pfizer and PATH Vaccine Solutions, and honoraria from Pfizer and Affinivax (donated to charity) for consulting on vaccine issues. L.S. is a co-owner of Sage Analytica, a small research consultancy which has done contracting work for Pfizer, GSK and AstraZeneca on vaccine evaluation modelling. A.J. declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Rid A, Saxena A, Baqui AH et al. Placebo use in vaccine trials: recommendations of a WHO expert panel. Vaccine 2014;32: 4708–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 2010;201:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peltola H, Aavitsland P, Hansen KG, Jonsdottir KE, Nokleby H, Romanus V. Perspective: a five-country analysis of the impact of four different Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugates and vaccination strategies in Scandinavia. J Infect Dis 1999;179: 223–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richardson V, Hernandez-Pichardo J, Quintanar-Solares M et al. Effect of rotavirus vaccination on death from childhood diarrhea in Mexico. N Engl J Med 2010;362:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Halloran ME, Longini IM. Struchiner CJ. Design and interpretation of vaccine field studies. Epidemiol Rev 1999;21:73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jackson LA, Nelson JC, Benson P et al. Functional status is a confounder of the association of influenza vaccine and risk of all cause mortality in seniors. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hernán MA, Robins JM. Causal Inference. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health 2015. http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/miguel-hernan/causal-inference-book/ (2 July 2016, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 1999;10:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Langmuir AD, Henderson DA, Serfling RE. The epidemiological basis for the control of influenza. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1964;54:563–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Govaert TM, Thijs CT, Masurel N, Sprenger MJ, Dinant GJ, Knottnerus JA. The efficacy of influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. JAMA 1994;272:1661–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nichol KL, Nordin JD, Nelson DB, Mullooly JP, Hak E. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in the community-dwelling elderly. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poland GA. If you could halve the mortality rate, would you do it? Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:378–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nordin J, Mullooly J, Poblete S et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalizations and deaths in persons 65 years or older in Minnesota, New York, and Oregon: data from 3 health plans. J Infect Dis 2001;18:665–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Viboud C, Miller MA, Jackson LA. Mortality benefits of influenza vaccination in elderly people: an ongoing controversy. Lancet Infect Dis 2007;7:658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simonsen L, Reichert TA, Viboud C, Blackwelder WC, Taylor RJ, Miller MA. Impact of influenza vaccination on seasonal mortality in the US elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jackson LA, Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Neuzil KM, Weiss NS. Evidence of bias in estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness in seniors. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35(2):337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Skowronski DM, De Serres G, Crowcroft NS et al. Association between the 2008–09 seasonal influenza vaccine and pandemic H1N1 illness during Spring-Summer 2009: four observational studies from Canada. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fireman B, Lee J, Lewis N, Bembom O, van der Laan M, Baxter R. Influenza vaccination and mortality: differentiating vaccine effects from bias. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:650–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Weiss NS, Neuzil KM, Barlow W, Jackson LA. Influenza vaccination and risk of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent elderly people: a population-based, nested case-control study. Lancet 2008;372:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jackson ML, Yu O, Nelson JC et al. Further evidence for bias in observational studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness: the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:1327–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baxter R, Lee J, Fireman B. Evidence of bias in studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness in elderly patients. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:186–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology.2010;21:383–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sankoh O, Welaga P, Debpuur C et al. The non-specific effects of vaccines and other childhood interventions: the contribution of INDEPTH Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:645–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Richardson DB, Keil AP, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cooper G. Negative control outcomes and the analysis of standardized mortality ratios. Epidemiology 2015;26:727–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tchetgen Tchetgen E. The control outcome calibration approach for causal inference with unobserved confounding. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:633–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Serres G, Skowronski DM, Wu XW, Ambrose CS. The test-negative design: validity, accuracy and precision of vaccine efficacy estimates compared with the gold standard of randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials. Euro Surveill 2013;18. Epub 2 October 2013. PubMed PMID: 24079398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Foppa IM, Haber M, Ferdinands JM, Shay DK. The case test-negative design for studies of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine. Vaccine 2013;31:3104–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Broome CV, Facklam RR, Fraser DW. Pneumococcal disease after pneumococcal vaccination: an alternative method to estimate the efficacy of pneumococcal vaccine. N Engl J Med 1980;303:549–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Serres G, Pilishvili T, Link-Gelles R et al. Use of surveillance data to estimate the effectiveness of the 7-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine in children less than 5 years of age over a 9 year period. Vaccine 2012;30:4067–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Belongia EA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in Wisconsin during the 2007–08 season: comparison of interim and final results. Vaccine 2011;29:6558–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kissling E, Valenciano M, Cohen JM et al. I-MOVE multi-centre case control study 2010–11: overall and stratified estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness in Europe. PLoS One 2011;6: e27622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology 2004;15:615–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chua BY, Wong CY, Mifsud EJ et al. Inactivated influenza vaccine that provides rapid, innate-immune-system-mediated protection and subsequent long-term adaptive immunity. MBio 2015. Epub 29 November 2015. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01024‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Benn CS, Netea MG, Selin LK, Aaby P. A small jab – a big effect: nonspecific immunomodulation by vaccines. Trends Immunol 2013;34:431–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cowling BJ, Nishiura H. Virus interference and estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness from test-negative studies. Epidemiology 2012;23:930–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goldstein E, Cobey S, Takahashi S, Miller JC, Lipsitch M. Predicting the epidemic sizes of influenza A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B: a statistical method. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O'Hagan JJ, Hernan MA, Walensky RP, Lipsitch M. Apparent declining efficacy in randomized trials: examples of the Thai RV144 HIV vaccine and South African CAPRISA 004 microbicide trials. AIDS 2012;26:123–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness - United States, January 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:32–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness - United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:119–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McLean HQ, Thompson MG, Sundaram ME et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during 2012–2013: variable protection by age and virus type. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:1529–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jackson ML, Rothman KJ. Effects of imperfect test sensitivity and specificity on observational studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2015;33:1313–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Valenciano M, Kissling E, Reuss A et al. The European I-MOVE Multicentre 2013–2014 Case-Control Study. Homogeneous moderate influenza vaccine effectiveness against A(H1N1)pdm09 and heterogenous results by country against A(H3N2). Vaccine 2015;33:2813–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Flannery B, Clippard J, Zimmerman RK et al. Early estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness -–United States, January 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:10–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gilca R, Skowronski DM, Douville-Fradet M et al. Mid-season estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H3N2) hospitalization in the elderly in Quebec, Canada, January 2015. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bateman AC, Kieke BA, Irving SA, Meece JK, Shay DK, Belongia EA. Effectiveness of monovalent 2009 pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1 and 2010–2011 trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines in Wisconsin during the 2010–2011 influenza season. J Infect Dis 2013;207:1262–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chung JR, Flannery B, Thompson MG et al. Seasonal effectiveness of live attenuated and inactivated influenza vaccine. Pediatrics 2016;137:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kissling E, Valenciano M, Falcao J et al. ‘I-MOVE’ towards monitoring seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccine effectiveness: lessons learnt from a pilot multi-centric case-control study in Europe, 2008–9. Euro Surveill 2009;14. Epub 28 November 2009. PubMed PMID: 19941774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kyaw MH, Lynfield R, Schaffner W et al. Effect of introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Schuck-Paim C, Lustig R, Haber M, Klugman KP. Effect of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on admissions to hospital 2 years after its introduction in the USA: a time series analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reichert TA, Sugaya N, Fedson DS, Glezen WP, Simonsen L, Tashiro M. The Japanese experience with vaccinating schoolchildren against influenza. N Engl J Med 2001;344:889–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Richardson V, Parashar U, Patel M. Childhood diarrhea deaths after rotavirus vaccination in Mexico. N Engl J Med 2011;365:772–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. VanderWeele TJ. Bias formulas for sensitivity analysis for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology 2010;21:540–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Halloran ME, Struchiner CJ, Longini IM. Study designs for evaluating different efficacy and effectiveness aspects of vaccines. Am J Epidemiol 1997;146:789–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Halloran ME, Haber M, Longini IM, Struchiner CJ. Direct and indirect effects in vaccine efficacy and effectiveness. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Young-Xu Y, Haber M, May L, Klugman KP. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination of infants on pneumonia and influenza hospitalization and mortality in all age groups in the United States. MBio 2011;2:e00309–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Griffin MR, Zhu Y, Moore MR, Whitney CG, Grijalva CG. U.S. hospitalizations for pneumonia after a decade of pneumococcal vaccination. N Engl J Med 2013;369:155–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rizzo C, Viboud C, Montomoli E, Simonsen L, Miller MA. Influenza-related mortality in the Italian elderly: no decline associated with increasing vaccination coverage. Vaccine 2006;24:6468–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Halloran ME, Longini IM. Public health. Community studies for vaccinating schoolchildren against influenza. Science 2006; 311:615–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Campbell H, Nair H. Child pneumonia at a time of epidemiological transition. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e65–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. World Health Organization. The Expanded Programme on Immunization' Geneva: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Haber M, An Q, Foppa IM, Shay DK, Ferdinands JM, Orenstein WA. A probability model for evaluating the bias and precision of influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates from case-control studies. Epidemiol Infect 2015;143:1417–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jackson ML, Nelson JC. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2013;31:2165–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Orenstein EW, De Serres G, Haber MJ et al. Methodologic issues regarding the use of three observational study designs to assess influenza vaccine effectiveness. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:623–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Arbogast PG, Martin SW, Edwards KM, Griffin MR. Decline in pneumonia admissions after routine childhood immunisation with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the USA: a time-series analysis. Lancet 2007;369:1179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ivers LC, Hilaire IJ, Teng JE et al. Effectiveness of reactive oral cholera vaccination in rural Haiti: a case-control study and bias-indicator analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e162–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Luquero FJ, Grout L, Ciglenecki I et al. Use of Vibrio cholerae vaccine in an outbreak in Guinea. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lucas ME, Deen JL, von Seidlein L et al. Effectiveness of mass oral cholera vaccination in Beira, Mozambique. N Engl J Med 2005;352:757–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:1737–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Feikin DR, Kagucia EW, Loo JD et al. Serotype-specific changes in invasive pneumococcal disease after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction: a pooled analysis of multiple surveillance sites. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rosenbaum PR. How to see more in observational studies: some new quasi-experimental devices. Annu Rev Stat 2015;2:21–48. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, Hayward R, Cook DJ, Cook RJ. Users' guides to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 1995;274:1800–04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Treanor JJ, Talbot HK, Ohmit SE et al. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccines in the United States during a season with circulation of all three vaccine strains. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:951–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Griffin MR, Monto AS, Belongia EA et al. Effectiveness of non-adjuvanted pandemic influenza A vaccines for preventing pandemic influenza acute respiratory illness visits in 4 U.S. communities. PLoS One 2011;6:e23085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Blyth CC, Jacoby P, Effler PV et al. Effectiveness of trivalent flu vaccine in healthy young children. Pediatrics 2014;133:e1218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hellenbrand W, Jorgensen P, Schweiger B et al. Prospective hospital-based case-control study to assess the effectiveness of pandemic influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination and risk factors for hospitalization in 2009–2010 using matched hospital and test-negative controls. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cortese MM, Immergluck LC, Held M et al. Effectiveness of monovalent and pentavalent rotavirus vaccine. Pediatrics 2013;132:e25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Correia JB, Patel MM, Nakagomi O et al. Effectiveness of monovalent rotavirus vaccine (Rotarix) against severe diarrhea caused by serotypically unrelated G2P[4] strains in Brazil. J Infect Dis 2010;201:363–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Patel M, Pedreira C, De Oliveira LH et al. Duration of protection of pentavalent rotavirus vaccination in Nicaragua. Pediatrics 2012;130:e365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Patel MM, Patzi M, Pastor D et al. Effectiveness of monovalent rotavirus vaccine in Bolivia: case-control study. BMJ 2013;346:f3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Klein NP, Bartlett J, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Fireman B, Baxter R. Waning protection after fifth dose of acellular pertussis vaccine in children. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1012–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Baxter R, Bartlett J, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Fireman B, Klein NP. Effectiveness of pertussis vaccines for adolescents and adults: case-control study. BMJ 2013;347:f4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Benin AL, O'Brien KL, Watt JP et al. Effectiveness of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in Navajo adults. J Infect Dis 2003;188:81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Doshi RH, Mukadi P, Shidi C et al. Field evaluation of measles vaccine effectiveness among children in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Vaccine 2015;33:3407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Pilishvili T, Bennett NM. Pneumococcal disease prevention among adults: Strategies for the use of pneumococcal vaccines. Vaccine 2015;33(Suppl 4):D60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]